Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 23

December 8, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of December 11, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Trade cards of old London.

• "I will never be vaccinated again": a teenaged diarist discusses the pain of her inoculation, 1901.

• Abigail Adams persisted: a letter from the then-First Lady defending a black servant from prejudice.

• Obelisks on the move: the manpower and engineering needed to move obelisks in ancient Egypt, Rome, and today.

• How competitive walking captivated Georgian Britain.

• Sewing shrouds : 19thc burial clothes.

• Image: Needlework sampler made English novelist and poet Charlotte Bronte .

• Harnessing the power of baubles and bling .

• " Patriotick Ladies , of Edenton in North Carolina" 1774.

• When the master danced with his cook: a country house Christmas in Dorset.

• The tragedy of prostitution in the Old West.

• Water to drink in the 1690s: fit only for invalids and chickens?

• Account of a very remarkable young musician in 1769 - who happens to be Mozart .

• Image: Women attaching the fabric to the wings of World War One biplanes , 1918.

• The African princess (and Queen Victoria's goddaughter) Sarah Forbes Bonetta .

• Fascinating blog to explore: commentary and transcribed daily diary of a Huguenot girl living in England, 1776.

• Image: Poignant Christmas card from the 38th Welsh Division showing a soldier dreaming of home, 1917.

• A brief history of the clothing and fabric trade in London, 1780-1914.

• Elizabeth Woodville , Queen of England.

• Map & rare book detective work: why experts now don't believe this is one of the first maps of America.

• The key to the Bastille has a place of honor...at George Washington's Mount Vernon.

• Just for fun: GIF: This knight at a Ren Faire took his responsibility to defend people from evil drones very seriously.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on December 08, 2017 08:32

December 7, 2017

Friday Video: Making a Plum Pudding, c1775

Susan reporting,

Since we're officially in the holiday season now, it seems like the appropriate time to share a video on how to make a traditional plum, or hunter's - the same pudding goes by different names - pudding. This is one of many excellent 18thc cooking videos produced by Townsends , an American purveyor of all kinds of 18thc and 19thc necessities for re-enactors and anyone who relishes the past, from reproduction wool cloaks to hunting knives to research books to (as mentioned in this video) the proper kidney suet for puddings.

Here you'll learn not only how to make a proper Georgian-style pudding, but also the histories of many of the ingredients. Who knew 18thc raisins were so different from their modern day descendants?

If you've received this video via email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Please click here to view the video.

Published on December 07, 2017 21:00

December 6, 2017

The French Corset in A Duke in Shining Armor

Phillipon, L'utile, marchande de corsets

Loretta reports:

Phillipon, L'utile, marchande de corsets

Loretta reports:Some time ago, Susan sent me the image you see, of a French corset seller with her wares, as an inspiration for the Dressmakers series I was working on. It looked perfect to me: not only the elegant 1830s corsets but the seller: her hair, her facial expression—that flirtatious glance. I kept it in view, especially when I was writing Leonie’s story, Vixen in Velvet , because she was the corset artiste of the trio.

However, I never wrote about the corset itself. At that time, I was focused on the seller, because my dressmakers were businesswomen.

But its moment came, in a flash of inspiration, when I was working on A Duke in Shining Armor , and had to get my heroine, Olympia, out of her wet clothes and into a fresh set of garments, right down to the underwear.

So far as I had been able to ascertain, ladies’ stays were white, as were all of their undergarments. The examples I’ve seen tend not to be especially sexy—except in the sense of being underwear in the 1800s and therefore sexy to the gentlemen—and not colorful. Maybe a little lace or embroidery would adorn, say, one’s chemise and petticoats, and pretty stitching, as in this example from the V&A online collection.

The undergarments I’d seen had all belonged to respectable women, though, including queens and aristocrats. Ordinary women were more likely to wear their clothes until they were not worth preserving.

Corset ca 1825-35

But what about the not-so-respectable women? What about the courtesans and others who had busy love lives? Expected to dress more dashingly and daringly, they might want to purchase less subdued styles, in colors or at least with colorful trim. This image told me that the Paris corset sellers were well able to oblige them.

Corset ca 1825-35

But what about the not-so-respectable women? What about the courtesans and others who had busy love lives? Expected to dress more dashingly and daringly, they might want to purchase less subdued styles, in colors or at least with colorful trim. This image told me that the Paris corset sellers were well able to oblige them.As to why Olympia ends up in French underwear, or why she’s wet in the first place—it’s all in the book.

While the above image appears in several places, including my Pinterest board for A Duke in Shining Armor , I recommend you click on this link to the FIT blog and scroll down. You can enlarge it to an enormous size!

Images: L’utile, marchande de Corsets , Charles Phillipon 1830, courtesy Les Musêes de la ville de Paris

White corset, ca 1825-35 courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum online collections.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on December 06, 2017 21:30

December 4, 2017

What Did Alexander Hamilton Wear for His Wedding to Elizabeth Schuyler in 1780?

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting, This post appeared earlier this fall on the blog that's connected to my web site, but since it was so popular there, I decided to share it here, too.

In early December 1780, Lt. Col, Alexander Hamilton finally received leave from his position as an aide-de-camp on Gen. Washington's staff, and headed north to Albany, NY to marry his fiancee Elizabeth Schuyler. It was his first leave away from the army since accepting the post in 1777. The young lieutenant colonel had performed his responsibilities so well that he'd become virtually indispensable to His Excellency, who only grudgingly granted the leave, and only for a few short weeks at that.

The wedding was small family affair, with the service taking in the parlor of The Pastures , the Schuyler family home overlooking the Hudson River. There are no surviving records of what either the bride or groom wore for the ceremony, or for the celebration that likely took place afterwards. The description of Eliza's gown that you'll find in my historical novel I, Eliza Hamilton is drawn from a suggestion for bridal dress for a fashionable winter wedding in a 1780 copy of The Lady's Magazine, the Georgian precursor of magazines like Vogue, and I also consulted with Janea Whitacre, the Mistress of the Mantua-Making Trade at Colonial Williamsburg .

In a letter that Alexander wrote to Eliza shortly before embarking for Albany, he asked if she'd prefer him to wear his uniform for their wedding, or civilian clothes. Alas, her reply is lost, so it's not known what decision she made for her groom. I'm guessing that she chose his military attire, given that it was a war-time wedding.

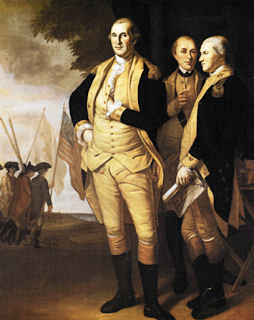

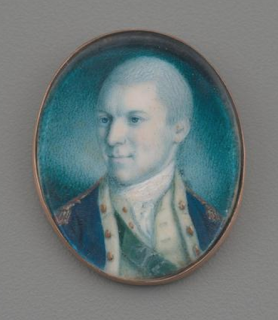

None of Alexander's uniforms from the Revolution are known to survive today. Uniforms from the war saw considerable hard wear, and only a handful from the entire Continental Army still exist. Among them is the uniform, above left, that was worn by another of Washington's aides-de-camp, and one of Alexander's close friends, Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman (1744-1786) of Maryland. As shown on a museum mannequin, the uniform is missing some key elements: a white linen shirt, gold officer's epaulettes, a sword and sword belt, boots, cocked hat, and the green ribbon sash worn by members of the general's staff. The portrait, above right, shows Gen. Washington himself, with the Marquis de Lafayette in the middle, and Lt. Col. Tilghman to the right, all in uniform.

Alexander's uniform at the time of the wedding was likely very similar. The miniature portrait by Charles Willson Peale of Alexander, below left, shows him in that uniform.

Now I have a totally unsubstantiated theory about this particular miniature: that Eliza may have seen it at some point during their courtship, and that perhaps Alexander even offered it to her, but that she rejected it for some reason - perhaps as not being worthy of her beloved. During the summer of 1780, he had another miniature painted at her request, showing him looking much more conventionally handsome and in civilian dress: see it here .

In any event, the epaulettes shown in the photo, lower right, did in fact belong to Alexander, and may well have been the same ones shown in the miniature portrait. Epaulettes were a relatively new feature of military dress in the 1770s, and were worn to make officers more visible to their men in battle. They were also considered to have less of the aristocratic baggage of the ribbons and sashes traditionally worn by British officers, and therefore were embraced by the Continental Army as being more democratic.

I saw Alexander's epaulettes on display this past summer at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown , VA. Even though the gallery was in half-light to protect the artifacts (and make the photos fuzzy!), the gold bullion still glittered despite being more than two centuries old. Imagine how those golden epaulettes and rows of polished buttons must have sparkled on Alexander's coat in the sunny parlor during the wedding, and imagine, too, how wonderfully dazzled Eliza must have been by her groom. Ahh, the sartorial power of a man in uniform....

Above left: Uniform worn by Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, c1777.

Above right: Washington, Lafayette, and Tilghman at Yorktown, by Charles Willson Peale, 1784. Both from the collections of the Maryland Historical Society; images from Maryland Historical Society.

Lower left: Miniature portrait of Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, by Charles Willson Peale,, 1777, Museum of the City of New York.

Lower right: Epaulettes Belong to Alexander Hamilton, c1777-1783, The Society of the Cincinnati. Photograph by Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on December 04, 2017 21:00

December 3, 2017

The Invalid Chair in A Duke in Shining Armor

Mechanical Chair

Loretta reports:

Mechanical Chair

Loretta reports:The basics of this post appeared a few years ago, as Merlin's Mechanical Chair . Clearly, the ingenious device stuck in my mind, because it ended up playing an important role in A Duke in Shining Armor .

The trick was figuring out how the thing worked. In the first place, early 19th century prose can be very hard to follow. It tends to be much less direct than our way of writing. In the second place, my brain is easily confused by physics and mechanics. Doubtless it took me a lot longer to learn how to drive this chair than it did the Duke of Ripley, in my book. I will leave it to you to read the instructions and make what sense of them you can.

Meanwhile, let us consider for a moment the commentary that follows the instructions. "Amusement"? Oh, yes, I figured that one out pretty quickly. But the suggestions for running the chair by means of a "very small and portable steam-engine" remind me of the way some people used to imagine us flying around on individual rocket-propelled devices in The Future. Having a 19th C steam engine powering my chair does not strike me as a safer prospect.

And then there's the idea of finding a way "to enable it to carry a small cannon, which should be, both for itself and its operators, completely unassailable by the enemy, as well as, by the singular rapidity of its evolutions, terribly and unusually destructive." Is your hair standing on end? Mine sure is. But let us remember that Great Britain was at war with Napoleon in 1811, and things weren't going so well. At home, people carried on with their lives, but that didn't mean they weren't aware of what was happening on the Continent, or didn't take seriously the possibility of invasion. As it turned out, Napoleon continued to be a danger until June 1815.

By the time of my story (1833), however, that's all in the distant past, and the chair is perfoming its dual functions of serving those with limited mobility as well as providing amusement.

Mechanical chair described

Mechanical chair described

Mechanical chair described

Mechanical chair described

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the captions will allow you to read at the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on December 03, 2017 21:30

December 2, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of November 27, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The Italian prince at Waterloo.

• The oldest treasures in twelve great libraries .

• Ten things you (probably) didn't know about Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites .

• A pair of short videos here and here for an extraordinary Victorian archery ensemble, complete with an original belt and accessories.

• One of NYC's greatest architectural losses: the birth, life, and death of the old Penn Station .

• Image: Author Edith Wharton's motor vehicle permit, France, 1915.

• English folklore: the fairy midwife and the magic ointment.

• Poet Phyllis Wheatley's writing desk most likely began as a card or tea table.

• Victorian doodles of Vauxhall pleasure gardens.

• Dying with "perfect resignation" in the Regency.

• Peas, please: the objects authors use most frequently for size comparison, past and present.

• Sexuality during the American Civil War : soldiers, wives, and intimate dreams.

• Image: Built in 1705 by Sir Christopher Wren, St. Paul's Dean's Stair appears to float.

• Wardrobes and the storage of clothes at a Swedish manor house, 1758.

• "A Lament Upon a Wombat ", 1869 (because that lamented wombat was the pet of artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti.)

• Love advice from the middle ages: how to tell if your 12thc lover is not that into you.

• Smallpox in the Sea Islands: Clara Barton and Columbus Simonds in South Carolina.

• Chopin's preserved heart may provide clues to his cause of death.

• Four generations of brides from a single family wore this handmade wedding dress from 1932.

• Image: Just for fun: For maximum impact and flair when reserving a parking space, try a peacock .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on December 02, 2017 14:00

November 30, 2017

The Bride's Dress in A Duke in Shining Armor

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Since my first blog post of the month is usually a fashion illustration, I shall begin my tour of A Duke in Shining Armor ’s historical background with what the heroine, Olympia, wore to the first wedding.

Seeking suitable bridal attire, I turned the pages of my French Fashion Plates of the Romantic Era . And there it was, exactly what I was looking for: an ensemble complicated enough, with a sufficiently elaborate hair arrangement, to express, in clothing, my heroine’s plight as well as her state of mind. It allowed, too, for what I deemed a satisfactory amount of comic effect. As some of you are aware, if there’s fashion description in my story, it’s there for a reason. If it doesn’t have a role to play—something to tell you, something to express, some action to perform—I skim over or skip it.

So there’s the dress that set me off. And there’s the dress. And there it is again.

Bridal Dress May 1833

Bridal Dress May 1833

As is evident, my search didn’t end with French Fashion Plates of the Romantic Era —because the book describes it as you see above, which is to say, not much. Since the source for these plates is the Petit Courrier des Dames (also published as Modes de Paris) for 1830-34, I commenced a search. That particular illustration did not appear in any of the online editions of the publication I could find, or in any of the several museum collections I searched.

But all was not lost. If you read here about the magazine , you’ll also learn about the kind of rampant stealing that went on. Long aware of the copying, I started investigating online for images from magazines for May-June 1833.

There it was, in a fashion print from the Ladies’ Cabinet , courtesy the Los Angeles Public Library online collection of Casey Fashion Plates. There it was, not called anything. But the date, May 1833, did correspond to the one in French Fashion Plates.

All very entertaining, but I needed a description—and at last I found it…sort of. There was the same dress, but in yellow, called an evening dress, in the Magazine of the Beau Monde . However, I decided it was a mis-coloring as well as a misprint, because here’s the description:

Figure III.—Evening Dress.—A white satin dress, corsage en pointe, trimmed with nœds; short sleeves with blonde sabots; a pelerine of blond extending over the sleeves. The hair in front separated and forming full side curls, elevated in close plaits on the summit of the head figuring a diadem ornamented with a branch of orange blossoms; a deep veil of blond surmounting the coiffure, and descending below the waist.

Bridal Dress mis-colored

Bridal Dress mis-colored

The orange blossoms would be a clue.

On my Pinterest Page you can see other illustrations I used while writing A Duke in Shining Armor . If you visit or sign up for my website blog , you’ll get some special material, exclusive material, and expanded/alternate versions of topics I’ve blogged about here.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on November 30, 2017 21:30

November 29, 2017

Lord Raby's "Great Silver Wine Cistern," c1705

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,While my last post featured the now-unknown 18thc child of a soldier living in a military encampment, this post features an 18thc child on the opposite end of the Georgian social ladder. Born into wealth and power, Charles James Fox (1749-1806) was the son of prominent politician Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, and Lady Caroline Lennox Fox, eldest daughter of the Duke of Richmond. Later in life, Charles became a noted statesman in his own right.

But as a child, Charles was much spoiled by his indulgent parents. One famously appalling incident is recounted in the wonderful biography Aristocrats (by Stella Tillyard, 1994, Noonday Press):

"Once a grand dinner was held at Holland House for some visiting foreign dignitaries. The Fox children were brought in for dessert. Charles, still a toddler in petticoats, said he wanted to bathe in a huge bowl of cream that stood on the table. Despite [his mother's] remonstrances, [his father] ordered the dish to be put down on the floor and there, in full view of some of Europe's most powerful politicians, the little boy slopped and slid to his heart's content in the cool, thick liquid."

I remembered little Charles in the cream when, while wandering on the internet, I came across this splendidly ostentatious silver wine cistern, upper left. A little more sleuthing led me to the publicity photo, bottom left, of a modern toddler named Leo, gleefully emulating young Charles Fox. As you can see from the photo, right, the wine cistern (today it would be called a wine cooler) is enormous. It measures over 51 inches across the top handles and contains over 70 kilograms of sterling silver, and can easily hold more than a dozen bottles of wine. It's also plenty large enough for most any small lordling's impulsive cream baths, and several of his friends, too.

But the wine cistern wasn't just a costly extravagance. Created in 1705-1706, this "great silver wine cistern" was commissioned by Thomas Wentworth, 3rd Baron Raby and Ambassador Extraordinary to Berlin between 1706-1701. Lord Raby's post was one of the most important abroad, and the cistern was part of his ambassadorial silver. The ambassador's silver service not only represented the wealth and magnificence of Queen Anne and the country she ruled, but its presence also honored foreign guests and dignitaries at state dinners. Made by Philip Rollos, Sr., in London, the cistern features a pair of patriotic British lions as well as the royal arms and cipher of Queen Anne.

Wine cisterns were the largest pieces in such a service, and so impressive that contemporaries waggishly likened them to boats and coaches. They weren't quite that large, but their size, containing so much silver, meant that some were melted down and remade into other items after the fashion for cisterns had passed. That, added to the fact that relatively few were made to begin with, means that today only a handful still exist.

Lord Raby's cistern remained in his family for three centuries. It was finally put up for auction in 2010, and was kept from leaving Britain by a fundraising campaign by Leeds Museums and Galleries, augmented with grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund. The cistern can now be seen on display at Leed's Temple Newsom House - though cream-bathing is not an option.

For much more about the history of Lord Raby's wine cistern, see the catalogue description by Sotheby's here .

Photos, left, courtesy of Sotheby's.Photo, right, ©2010 by Clara Molden for The Telegraph.

Published on November 29, 2017 21:00

November 28, 2017

A Duke in Shining Armor Official Debut

A Duke in Shining Armor

Loretta reports:

A Duke in Shining Armor

Loretta reports:Today’s the big day for A Duke in Shining Armor , the first in my Difficult Dukes series. Though it’s listed as a December book and though I’ve already seen it on some bookshop shelves—and happily signed the copies I found—today’s the official day.

You can read about the Difficult Dukes series here at my website . On the book’s website page , you'll find a back cover plot summary and an excerpt. And my website blog has and will continue to have posts related to the book.

Following is my book tour, actual and virtual:

Actual Tour

I'm looking forward to meeting readers at these events. I hope to see you there!

Loretta Chase & Caroline Linden: A Conversation

7 PM Wednesday 29 November 2017

Bacon Free Library

58 Eliot Street

Natick MA 01760

508-653-6730

Romance Event with authors Sarah MacLean, Maya Rodale, and Megan Frampton

7-8pm Thursday 30 November 2017

Savoy Bookstore and Café

10 Canal Street

Westerly RI 02891

401-213-3901

Romance & Respect

—with Joanna Shupe, Tessa Bailey, Megan Frampton, Tracey Livesay

7-8pm Wednesday 6 December 2017

Strand Bookstore

828 Broadway (& 12th Street)

New York NY 10003

212-473-1452

~~~

Virtual Tour

Cathy Maxwell & I will be discussing heroines at USA Today’s Happy Ever After. Details TBA

Heroes and Heartbreakers has published a short version of the excerpt (in case you’re pressed for time).

At RT Reviews, I offer the alarming truth about dukes in the early 19th century. Also, RT VIP Salon interviewed me; however, this material is available only to subscribers.

My work is mentioned at Racked, in an article about the term bodice rippers .

Publishers Weekly interviewed me for their article about consent in romance .

A Duke in Shining Armor has also received some very good reviews, including starred reviews in Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and Library Journal, and a Desert Isle Keeper Review at All About Romance.

That's all I can think of for now, but you can expect some book-related blog posts in the near future, here as well as at my website blog.

Published on November 28, 2017 07:58

November 26, 2017

The Littlest Camp Followers, c1775

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,One of the things I appreciate most about the still-new Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is the way the artifacts, videos, and exhibits are so much more inclusive than many more traditional exhibitions devoted to the Revolution and life in 18thc America. The stories told by the MoAR feature the familiar heroic actors like George Washington, but there are also many other individuals - including Native Americans, African Americans, and women - whose contributions and sacrifices have been too often overlooked, forgotten, or purposefully ignored.

This tiny earthenware lamb (only a few inches long) represents a group that was very much involved in the war, yet seldom mentioned: the children of soldiers. Along with their mothers and soldier-fathers, these children - often born during a campaign - were a familiar feature of 18thc armies. While the term "camp follower" conjured up titillating images like this, the reality was that the majority of the women traveling with the army were married to enlisted men; these women were often employed in laundering, food preparation, and tending the sick and wounded. Their children, of course, had little choice in the matter; they simply "followed the drum" because they followed their fathers.

Children appear in contemporary paintings of military scenes like the one shown here. The reality was likely much more rough-and-tumble, and combined with the real possibilities of danger, disease, and death, yet their presence at the time was unquestioned in a way that seems unfathomable to us today.

The lamb toy was excavated from a British Revolutionary War campsite near New York City, a British stronghold through much of the war. Made in England of white salt-glazed stoneware, the lamb could have crossed the Atlantic on board a troop ship with its owner, or been purchased in a New York shop.

The name of the lamb's young owner isn't known, nor are the circumstances of how it was lost or left behind at the camp. Lost toys are nothing new, nor, sadly, are children in the middle of wars. Still, I hope that both that long-ago child and his or her parents returned safely from the war, even if the lamb remained behind as a poignant reminder of a child in the middle of an adult conflict.

Thanks to Philip Mead, Chief Historian of the Museum of the American Revolution, for suggesting this post.

Left: Toy Lamb, England, 1750-1800, on loan from the New-York Historical Society to the Museum of the American Revolution.

Right: British Infantrymen of a Royal Regiment in an Encampment, painter unknown, c1760, National Army Museum.

Published on November 26, 2017 18:10