Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 25

November 1, 2017

Patriotism, French Fashion, and Mrs. Morris's Pouf, c1782

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,One of those history-myths that refuses to die states that, during the years of the American Revolution, women of every class wore "homespun" to be patriotic. According to this myth - made popular in the 19thc as later generations looked fondly (and imaginatively) backwards to their ancestors - these women were paragons of colonial self-sufficiency. They not only herded and sheared sheep, processed, spun, dyed, and wove the wool and likewise process flax into linen cloth, but cut and stitched every garment worn by their equally patriotic family.

Well, no. Even if there were enough hours in the day, few women possessed the training to achieve all this. Most of the steps in 18thc clothing production were performed by highly skilled professional tradespeople, and most of the fabric - whether linen, wool, silk, or cotton - worn by Americans, rich or poor, had been produced elsewhere, and imported.

This didn't change with the Revolution. While restrictions to trade limited new imports, there was still plenty of pre-war stock in warehouses and shops. Wartime deprivations might have made the cost of new fabric prohibitive to many families, but that meant refashioning and refurbishing, patching and mending what was already owned. Fabric was valued, and there was no disgrace in making a new gown in 1778 from 1750 fabric.

For a wealthy woman like Mary White Morris (c1749-1827), left, the Revolution likely had little impact on her wardrobe, and she wasn't wearing homespun, either. Married to entrepreneur and banker Robert Morris, Mary was known as a lady who "ruled the world of fashion with unrivaled sway" - at least that part of the fashionable world centered by Philadelphia. This portrait of her by Charles Willson Peale was painted towards the very end of the Revolution, around 1782, yet she is shown in casually luxurious splendor. She is wearing fanciful, Turkish-inspired clothing that was the height of French fashion - a lace-trimmed silk sultana , a gown edged with fur, a silk sash - and her silk headdress, or pouf, is an elaborate concoction of silk, strands of glass pearls, feathers, and paste-jewel ornaments in the shape of stars and a crescent moon, with a trailing veil or scarf.

Yet by following the French fashion for dramatic hair, poufs, and turquerie, Mary Morris was not only following the lead of that international trendsetter Queen Marie Antoinette, but she was making a political statement of her own as well. The French were America's allies, and without French military assistance, the American cause would not have been successful. Mary's husband was much involved in both the war and creating the new country's government, and among their closest friends was the Marquis de Lafayette. Dressing like a Parisian for a portrait was patriotic.

But patriotic fashion reached back from Philadelphia to Paris, too. The French rejoiced along with the Americans in their victory over the British, and French women celebrated by wearing clothing inspired by the new country (or at least named for it.) This detail, left, from a French fashion journal shows one of the latest styles for 1783: Chapeau à la Pensilvaine (Hat in the Style of Pennsylvania).

Thanks to Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell for her assistance and inspiration for this post, and for peering at Mrs. Morris's portrait with me last week at the Second Bank Portrait Gallery. For more 18thc French fashion, check out Kimberly's splendid fashion history, Fashion Victims (Yale University Press.)

Above: Mary White Morris by Charles Willson Peale, c1782, National Park Service Museums.

Below: Detail, Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français. 39e Cahier des Costumes Français, 10e Suite des Coeffures à la mode en 1783. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Published on November 01, 2017 21:00

October 30, 2017

Sir James Tillie's Strange Interment

Sir James Tillie's mausoleum

Loretta reports:

Sir James Tillie's mausoleum

Loretta reports:Looking for a suitable historical topic for Halloween that didn’t involve burning nuts or bobbing for apples, I found myself considering the subject of earthly remains and what to do with them. In Sir James Tillie's case, it was definitely not the usual thing.

A drawing of his mausoleum, along with the same exact account of his ideas for his dealing with his corpse, appeared in various 19th C magazines over the years, like the 1828 Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine and the Ladies’ Pocket Magazine of 1837 .

Other versions of the story appear in An Illustrated Itinerary of the County of Cornwall as well as this one from The Monthly Review 1803:

***

"Mr. Tilly, once the owner of Pentilly-House, was a celebrated atheist of the last age. He was a man of wit, and had by rote all the ribaldry and common-place jests against religion and scripture, which are well suited to display pertness and folly, and to unsettle a giddy mind; but are offensive to men of sense, whatever their opinions may be; and are neither intended nor adapted to investigate truth. The brilliancy of Mr. Tilly's wit, however, carried him a degree further than we often meet with in the annals of prophaneness. In general, the witty atheist is satisfied with entertaining his contemporaries; but Mr. Tilly wished to have his sprightliness known to posterity. With this view, in ridicule of the resurrection, he obliged his executors to place his dead body, in his usual garb, and in his elbow chair, upon the top of a hill, and to arrange on a table before him, bottles, glasses, pipes, and tobacco. In this situation he ordered himself to be immured in a tower of such dimensions as he prescribed, where he proposed, he said, patiently to wait the event. All this was done; and the tower, still enclosing its tenant, remains as a monument of his impiety and prophaneness. The country people shudder as they go near it.”

Lady's Magazine

Lady's Magazine

You might also enjoy this version (please scroll down) by Sabine Baring-Gould in his 1906, Book of Cornwall.

And then there was the discovery of human remains on the site , as reported by the BBC a few years ago.

Photograph: Mausoleum of Sir James Tillie of Pentillie Castle by Rod Allday. Creative Commons license. You can get more information about the building here at Images of England .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 30, 2017 21:30

October 29, 2017

A "Knitted Gift" Made by Eliza Hamilton in her Nineties, c1854

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,For those of us who knit, embroider, crochet, and sew, October is the get-serious month for finishing handmade gifts for the coming holiday season. But as hectic as that can be, there's also a special satisfaction in putting a bit of yourself into something you've created, a one-of-a-kind memento that links the giver and the recipient in a way that a purchased present never can. If you're a "maker," you understand.

My guess is that Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (1757-1854), the wife of Alexander Hamilton, and the heroine of my new historical novel I, ELIZA HAMILTON , understood this, too. For 18thc American women of the elite class like Eliza, handiwork could be as practical as mending worn garments or stitching baby garments, or as extravagant as embroidery incorporating imported gold lace and silk thread. While nearly all women of Eliza's generation and social rank would have been taught at least rudimentary sewing and fancier needlework, for some it became a form of self-expression as well.

The objects these women created were a way that they proudly shared themselves, their accomplishment, and their love with friends and family. Often the most treasured of heirlooms are the quilts made in honor of a marriage, a tiny smocked infant's dress, or an embroidered mourning picture commemorating a lost parent.

Although there are no surviving written records of what needlework meant to Eliza, I suspect that it was important to her, and that not only did her practical and industrious nature mean that she was seldom without some bit of handwork, but also that she excelled at it. I've already shared examples of her needlework executed while she was in her early twenties: this embroidered mat that surrounds her future husband's miniature portrait, and the embroidered handkerchiefs that she made for their wedding. These are the work of talented stitcher who clearly relished her time with her needle.

This knitted pillow cover, however, tells a much different story. The cover is believed to have been made around 1854, shortly before her death at age 97. Although Eliza was said to have been sharp-witted to the very end of her long life, it's evident from this that age had taken its toll on her eyesight. It's telling that she chose to knit the cover rather than embroider. Knitting is a more forgiving craft that embroidery, and the repetitive motions of knitting are less demanding than the precision of a needle through linen.

Yet as a knitter myself, I look at this pillow cover and see what a challenge it must have presented. There are dropped, repeated, and twisted stitches, stitches that are mysteriously increased and others that disappear. The colored stripes aren't consistent, the rows irregular and misshapen. Instead of neatly mitering the corners and making a single, shaped square, the piece was done in strips that were sewn together, with woven ribbons sewn over the seams (perhaps by someone else helping with the completion?) to soften the awkward joinings. But despite all the mistakes, what I see most is the elderly Eliza's determination and persistence to make something special for an acquaintance, no matter how difficult the actual execution must have been for her.

Fortunately the recipient understood, too. Britannia W. Kennon (1815-1911) was the great-granddaughter of Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, wife of George Washington. Britannia is a fascinating woman in her own right, and deserves a future blog post of her own. In 1848, Eliza and her daughter Eliza Hamilton Holley moved from New York to Washington, DC, and rented a house on H Street owned by Britannia. The three women, sadly, had much in common. All three had been widowed at relatively early ages: Eliza's husband Alexander had died at age 48 (approximately; his birthdate is uncertain) of wounds suffered in his duel with Aaron Burr in 1804; Sidney Holly had died in 1842 in his early forties, and Britannia's husband, Commodore Beverley Kennon, had been killed in a shipboard explosion in 1844, less than two years after their marriage.

Britannia took the legacy of her family's past seriously. The elegant house in which she lived, Tudor Place, had been built by her parents with an inheritance from George Washington, and the furnishings included many pieces that had belonged to the Washingtons at Mount Vernon. Britannia arranged and displayed these objects at Tudor Place, taking care to record the details about each on hand-written paper tags.

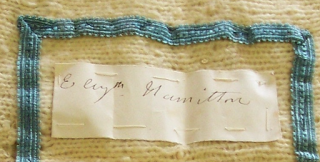

Eliza's knitted pillow cover joined Britannia's collection. Perhaps it earned its place there because Eliza, long before, had been friends with Martha Washington, or because her late husband's numerous accomplishments gave luster to her own name by association. Perhaps, too, Britannia cherished the cover simply from respect and regard for Eliza herself. Preserved with the pillow is a small clipped paper, right, with Eliza's signature - "Elizth Hamilton", and on the back is a label in Britannia's handwriting: "Made by/Mrs. Alexander Hamilton/a short time before her/death, for Mrs. Kennon."

Today Tudor Place Historic House and Garden is a National Historic Landmark, and open to the public; see their website here for more information. Eliza's "knitted gift" is now part of Tudor Place's collections. Information for this post came from unpublished sources from the Tudor Place archives, and from an annotated edition of Britannia W. Kennon's reminiscences that currently being compiled for future publication. Many, many thanks to Curator Grant Quertermous for his generous assistance with this post. And thanks, too, to Hannah Boettcher, Public Programs Coordinator, Museum of the American Revolution, for suggesting that I seek out Eliza's pillow cover.

Above: Pillowcase, made by Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton before 1854. Linen, wool. Courtesy of Tudor Place Historic House & Garden.

Read more about Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton in my latest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on October 29, 2017 17:00

October 28, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of October 23, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The ghost of Kit Carson: women's history along the Santa Fe trail.

• Medieval graffiti : demon traps, spiritual landmines, and the writing on the wall.

• Emily Dickinson , poet and baker.

• "The Hatpin Peril " terrorized men who couldn't handle 20thc women.

• Inside London's sumptuous Drapers' Hall .

• Image: This 1770s porcelain macaroni's wig bag is bigger than the archway (though not perhaps his fashion sense.)

• What does the painting Surrender of Lord Cornwallis have to do with author Edith Wharton ?

• Final telegraph transmissions from on board the Titanic .

• Explore the diaries of Miss Fanny Chapman , a 30-something single woman living with her aunt in Regency England.

• George Washington's mausoleum : Congressional debates over the work of monuments.

• Video: "I remember the interior of that cabin": how the curators at Monticello used a diary to furnish a reconstructed slave cabin .

• The "petting parties" of 1920s flappers that scandalized many Americans.

• Death takes wing: birds and the folklore of death.

• The poet Shelley's spyglass , found in the wreck of his boat.

• Eradicating smallpox : history in objects.

• Image: A daunting to-do list from Thomas Edison's 1888 journal.

• Lord Nelson's lasting legacy in London.

• Eliza Ross, the forgotten female "burker," who, with her partner, had murdered her 84-year-old lodger to sell her body to anatomists, 1831.

• Skull cup associated with Lord Byron heads to auction.

• Image: Princess goals: Prince Margaret's morning routine, 1955 (from the book Ma'am Darling by Craig Brown.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on October 28, 2017 14:00

October 26, 2017

Friday Video: Strip Tease on a Trapeze, 1901

Susan reporting,

Today we think of Thomas Edison (1847-1931) as a masterful inventor of practical things, like the light bulb, that changed the world. But he was also a shrewd businessman who wasn't afraid to apply his inventions (like the motion picture camera) to pure entertainment. He gave the people what they wanted, and his short films included boxing cats, kissing couples, and this film featuring Charmion, one of the more famous vaudeville stars of the early 20thc.

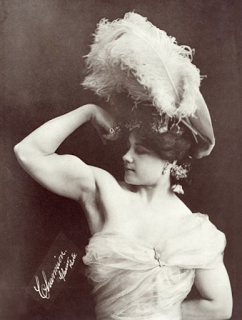

Charmion was the stage name of Laverie Vallee (1875-1949), who not only dazzled audiences with her trapeze acts, but also with her well-developed muscles. In an era where the ideal woman was soft and round and confined by her corset, Charmion was a "strongwoman" who struck the same exaggerated poses as strongmen to show off the well-defined muscles in her arms, shoulders, and backs.

This short film shows her most famous act, performed on a trapeze. Beginning in full 19thc street dress, Charmion energetically sheds them all while on a trapeze, piece by piece falling away (I suspect an early version of Velcro in use) until she's left in nothing but a flesh-colored acrobat's leotard. This was hot stuff in 1900, and the humorous reactions of the two men who are nearly overcome in the balcony probably weren't that far off from from reality for some audiences.

And yes, this being 2017, not 1901, all two minutes are now entirely suitable for viewing at work.

If you receive this video in an email, you may see only an empty box or a blank space where a video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on October 26, 2017 21:00

October 25, 2017

Funeral Etiquette in the Early 19th Century

Graves at Kensal Green CemeteryLoretta reports:

Graves at Kensal Green CemeteryLoretta reports:At some point early in my career, someone informed me that women did not attend funerals in early 19th century England. However, while researching funerals recently, I learned that there was disagreement on the matter.

The Gentleman and Lady's Book of Politeness and Propriety of Deportment of 1833 (a French work translated into English) offers this:

***

When we lose any one of our family, we should give intelligence of it to all persons who have had relations of business or friendship with the deceased. This letter of announcement usually contains an invitation to assist at the service and burial.

On receiving this invitation, we should go to the house of the deceased, and follow the body as far as the church. We are excused from accompanying it to the burying-ground, unless it be a relation, a friend, or a superior…

At an interment or funeral service, the members of the family are entitled to the first places; they are nearest to the coffin, whether in the procession, or in the church. The nearest relations go in a full mourning dress. It is not customary at Paris for women to follow the procession; and, nowhere do they go quite to the grave, unless they are of a low class. A widower or a widow, a father or mother, are not present at the interment, or funeral service of those whom they have lost. The first are presumed not to be able to support the afflicting ceremony; the second ought not to show this mark of deference.

The Gentleman’s Quarterly Review of August 1836 takes a different view. Regarding the Rev. W. Greswell’s Commentary on the Order for the Burial of the Dead, the reviewer has this to say:

We hope the hints relative to the nonattendance of females of the higher classes at funerals, will produce its due effect; it is a direct avoidance of a great Christian duty, which too often arises from selfish and effeminate motives of indulgence. Mr. Greswell ought, however, to have considered that if the females do not attend the funeral of their departed relatives, like the male mourners, yet they bear a far greater share previously in their attendance on the sick and dying ; and show a tenderness and firmness that the other sex cannot always boast: thus they are often incapacitated by distress, added to watchfulness, weariness, and even sickness, from attention to these last duties. This is a sound and legitimate cause of absence; but it is the only one.

*Originally published in France.

Photograph Photo copyright © 2017 Walter M. Henritze III

Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

Published on October 25, 2017 21:30

October 24, 2017

The Diamond Rock Octagonal School, 1818

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Education was important to the first generations of Americans after the Revolution. True, there were a great many things to be sorted out by the new country - everything from minting money to debating a standing army to creating public works for safe drinking water. But the ultimate success of the Revolution and the new government that followed would depend on citizens who could think and make important decisions for themselves. Literacy was key.

Among those who recognized the need for education was John Adams, who wrote the following in a 1786 letter:

"But before any great things are accomplished, a memorable change must be made in the system of Education and knowledge must become so general as to raise the lower ranks of Society nearer to the higher. The Education of a Nation, instead of being confined to a few schools & Universities, for the instruction of the few, must become the National Care and expence, for the information of the Many...."

The same belief was expressed on every level of early American society, and not just in the affluent and sophisticated coastal cities. While only twenty miles from Philadelphia, the Great Valley region of Chester County was still farms and forest in 1818. Yet in that year, a group of thirty-four individuals from the Great Valley came together to subsidize the creation of a school for the local children.

To be sure, thoughtful citizenship wasn't the only reason for the school. Being able to read, write, and cipher were important skills for farmers, too, and being able to read the Bible was as important as reading newspapers. Education was also seen as "improving," a way to better one's self and rise higher in the world. What parents - then or now - don't want that for their children?

None of these individuals founding the school would have been considered wealthy. The original subscription list shows that only one contributor paid thirty dollars, with the majority offering between three and five dollars, and one subscription of only fifty cents. But together, they raised the amount necessary to build a single-room schoolhouse: $260.93. Members of the community continued to contribute, whether in money to pay the teacher's salary, or by offering a spare room for the teacher's lodgings, or by cutting wood to burn for heat during the winter months. From the beginning, the school was considered a "free school", without a religious affiliation, and open to all boys and girls in the area.

The little schoolhouse still stands today, upper left, and is known as the Diamond Rock Octagonal School. Its single room is in fact an octagon, a forward-thinking design for schools at the time. Windows supplied light from every direction, and heat came from a wood-burning cast-iron stove, lower left, in the center of the room. The teacher's tall desk, upper right, stood nearby, where he or she (the list of teachers between 1818 and 1864 shows the post was nearly equally divided between women and men) could survey the students.

And what a task that must have been. Students sat on backless benches, divided by age and ability into groups that faced one of the eight walls for study and assignments. When it was each group's turn to be taught, they would swivel around on their benches to face the teacher. Their ages ranged from small children to young adults, and during harvest and planting seasons, the older students would be kept home to help with crops. Tradition says that at its greatest capacity, the school could accommodate sixty children - a staggering number in a single room, and a testament to the dedication and adaptability of those early teachers.

The schoolhouse remained in use until 1864, when newer, more modern schools were built nearby. Over time, the little building fell into disrepair, and late 19thc photographs show that it had deteriorated into a roofless shell. Around 1915, the artist Wharton Esherick became involved in the restoration of the school and used it as his studio for several years. He added the concrete floor, and was also responsible for the diamonds in the shutters and the iron work on the windows and door.

The school soon found another savior in Emma W. Wersler, a local woman whose mother and sister attended the school and was a descendent of one of the original subscribers. She supervised the school building and its restoration, and arranged for original artifacts - books, the teacher's desk and chair, the wooden buckets for drinking water, lower right - that had been scattered when the school closed to be returned for display. In 1918, the school reopened as a museum and historic site.

Overseeing the maintenance of the school was the Diamond Rock Old Pupils Association, which also served as an alumni group for former students. These included three physicians, two ministers, and a congressman - ample proof that "improvement" could in fact take place in a one-room schoolhouse.

For more information about the Diamond Rock Octagonal Schoolhouse, including hours when it is open to the public, visit the website here .

Many thanks to Susanna Baum for her assistance with this post.

Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott

Published on October 24, 2017 18:00

October 23, 2017

A Visit with the late Duke of Sussex

Tomb of Duke of Sussex at Kensal Green Cemetery

Loretta reports:

Tomb of Duke of Sussex at Kensal Green Cemetery

Loretta reports:In my recent post about London’s Kensal Green Cemetery , I mentioned the Duke of Sussex (1773-1843). This son of George III made the place fashionable by deciding to be buried there rather than at Windsor. In life, as in death, Prince Augustus Frederick went his own way.

Though he was a big guy—six foot three and burly—he wasn't hale and hearty. Yet the asthma that plagued him also helped make him “the most consistently Liberal-minded person of the first half of the nineteenth century.” His brothers championed the Whigs in youth, but mainly in rebellion against their father. When he no longer had power over them, their politics went the other way. Not so with Prince Augustus.

Thanks to the asthma, he spent much of his early life abroad and had no military career. He matured free of the influences that shaped his brothers’ politics. Equally important, he had far more time to cultivate his mind. He became a person who supported abolition of the slave trade, Catholic emancipation, parliamentary reform, and many other progressive ideas. These views won him the hostility of, basically, the entire Establishment, including his brothers. They cost him financially, too.

On the other hand, he wasn’t unlike his brothers when it came to women. At age twenty, he fell madly in love with Lady Augusta Murray, daughter of the Earl of Dunmore, and married her, in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act, which required the monarch’s consent. King George III refused, and a decree was issued, annulling the marriage.

Nonetheless, the prince stuck with his woman...until he had to choose between getting the title Duke of Sussex—with £12,000 per annum—and her and their two children. In 1801 he chose the title and money. By 1806 he was bringing legal action to prevent her calling herself the Duchess of Sussex. (She was given a lesser title instead.) By 1809 he took the children to live with him. Still, he didn’t remarry until 1830, after she was dead. The second marriage, to Lady Cecilia Buggin, was problematic, too, until Queen Victoria recognized it in 1840 and made the lady the Duchess of Inverness.

Duke of Sussex , Knight of the Order of the Thistle

Duke of Sussex , Knight of the Order of the Thistle

The Queen adored her uncle: “When he was dying she drove down in tears to Kensington Palace in an open carriage to inquire for him, although she was hourly expecting the birth of her third child.”

He went his own way in death, too, and it wasn't only in the choice of burial site. In keeping with his very progressive views on dissection, he gave directions in his will for his body to be opened and studied “in the interests of science.” In keeping with his ideals, his is a modest tomb. (So modest that we apparently forgot to take a picture of it.)

For the bulk of this post, and the quotations, I’m indebted to Roger Fulford’s Royal Dukes . When online sources proved unsatisfying—especially regarding the duke’s personality—I remembered this very enjoyable book.

Images: The tomb of Prince Augustus Frederick, Kensal Green Cemetery

Photo by Stephencdickson, Creative Commons license

G.E. Madeley, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex wearing the robes of a Knight Companion of the Order of the Thistle .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 23, 2017 05:23

October 21, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of October 16, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Advice for English ladies in India, 1847.

• A handy guide to vampires from the Royal Armouries.

• The spinster's numeration table : a guide for 19thc men.

• Blowing a cloud: pipes in Georgian London.

• Image: Forget Gatsby: F.Scott Fitzgerald's legacy is secured by this note in which he conjugates the verb "to cocktail."

• Striking images by portrait photographer Olive Edis, who was commissioned to document the women's war effort in France and Belgium during World War One.

• How Eleanor Roosevelt and Henrietta Nesbitt transformed the White House kitchen .

• Talking corpses : how even in death, women's testimony was considered less credible than men's.

• Conservation of Queen Victoria's petticoa t.

• Image: Print showing the interior of a fashionable London haberdashery in 1825.

• Among the rarest and oldest books in Horace Walpole's collection: two 16thc books of swan marks.

• How a gilded-age heiress became the " mother of forensic science ."

• The whimsical world of garden follies .

• Heroin, opium, mercury, and cocaine were among the ingredients in Victorian medicines that "soothed" the nation's children.

• Image: Women's Home Defence Corps , 1940.

• To dine at Kew: the meals of George III.

• Napoleon's "Kindle": the miniature traveling library that he took on military campaigns.

• First look at the newly restored York Mansion House .

• In Boston in 1765, there was one tavern for every 79 adult men; the importance of taverns .

• Just for fun: Sky-high modern paper wigs inspired by 18thc excess in fashion.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on October 21, 2017 14:00

October 19, 2017

Friday Video: Frankenstein, according to Thug Notes

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:If you have not already discovered Thug Notes, and don’t have a problem with Language for Mature Audiences Only, you might want to check out the videos. Host Sparky Sweets, Ph.D., takes on the classics, summarizing and analyzing them, “original gangster” style, in about five minutes.

As part of my Halloween countdown, I offer his take on Frankenstein.

Video: Frankenstein - Thug Notes Summary and Analysis

Image: still from YouTube video

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on October 19, 2017 21:30