Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 28

September 27, 2017

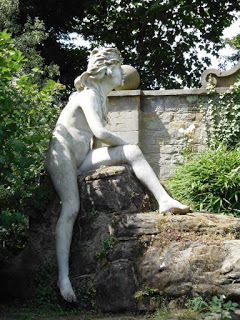

The Naked Ladies of York House, Twickenham

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:I’m happy to say that our trip to London held many, many excellent surprises, not least among them the Naked Ladies at York House in Twickenham. The first surprise was learning that York House wasn’t the home of any Dukes of York. It was the home of the Yorke family, and built for one of King Charles I’s courtiers. Since then, it’s had more than its share of owners—including Anne Seymour Damer , a sculptor who was Horace Walpole’s great friend. (No, I didn’t get to Strawberry Hill this time. Next time, I hope.)

But among the artists, aristocrats, and would-be monarchs who called York House home, the one who caught my attention was Sir Ratan Tata—because he’s the one who’s responsible for installing these statues in the garden. They’ve led an exciting life, certainly. They belonged originally to

Whitaker Wright

, who killed himself with cyanide after a conviction for fraud. Sir Ratan, who ran a then-legal opium importing business, socialized with King George V. During WWII, the ladies had to be camouflaged under some sort of dark substance, to avoid attracting the attention of German bombers.

But among the artists, aristocrats, and would-be monarchs who called York House home, the one who caught my attention was Sir Ratan Tata—because he’s the one who’s responsible for installing these statues in the garden. They’ve led an exciting life, certainly. They belonged originally to

Whitaker Wright

, who killed himself with cyanide after a conviction for fraud. Sir Ratan, who ran a then-legal opium importing business, socialized with King George V. During WWII, the ladies had to be camouflaged under some sort of dark substance, to avoid attracting the attention of German bombers.I will admit that some of the poses puzzled us—and we’re not the only ones. Those responsible for installing the statues were puzzled, too, because they had to figure out how to arrange the figures without guidance from either the artist or written instructions. Furthermore, these Naked Ladies were meant to be part of a larger ensemble, but the other statues went elsewhere—possibly with the instructions. Still, while the arrangement may not be what the artist originally intended, it certainly does stop a visitor in her tracks.

You can learn more about the statues and their history at the

York House Society website

, in this

PDF

(this material appears on a sign near the statues as well, which proved impossible to photograph), at the

Twickenham Museum

site, and of course at Wikipedia, where you can learn more about

York House

as well as the

Naked Ladies

.

You can learn more about the statues and their history at the

York House Society website

, in this

PDF

(this material appears on a sign near the statues as well, which proved impossible to photograph), at the

Twickenham Museum

site, and of course at Wikipedia, where you can learn more about

York House

as well as the

Naked Ladies

.All images: Photo copyright © 2017 Walter M. Henritze III

Please click on images to enlarge.

Published on September 27, 2017 21:30

September 25, 2017

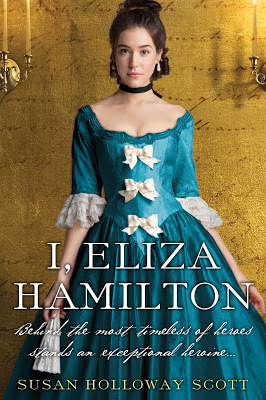

It's Publication Day for I, ELIZA HAMILTON!

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,At last, at last: my new historical novel, I, ELIZA HAMILTON is now available via on-line websites and in bricks-and-mortar stores, and in every format including print, ebook, and audiobook.

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books-a-Million

Book Depository (If you live outside the US, Book Depository ships worldwide for free.)

Google Play

IBooks

Indiebound

If you need to be tempted further, you can read a description as well as the prologue and first chapter here . You'll find plenty of additional background about Eliza and Alexander Hamilton and the tumultuous times in which they lived here on my website blog. There's also a Behind-the-Book feature at BookPage.

So far the initial reviews have been wonderful, including a starred review in Publishers Weekly and more than 65 five-star early-reader reviews on Goodreads .

But the only opinion that matters now belongs to you, dear readers.

Eliza is ready to share her story, and oh, she has such things to tell....

Published on September 25, 2017 21:00

September 24, 2017

Temple Bar Returns

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:In Dukes Prefer Blondes , I mention Temple Bar, a gateway that stood where Fleet Street meets the Strand. Through it have passed, along with the usual traffic, monarchs dead and alive. On the main arch, on iron spikes, traitors’ heads were on display.

The structure still exists, as I set out to prove to my satisfaction during my stay in London, and this existence, to me, is a miracle. It is London’s only surviving gateway, and the story of its survival includes a trip to Hertfordshire.

Built in 1672, the time of King Charles II, it was taken down, stone by stone, in 1878, because it was in the way. It had for years obstructed traffic, and now it was hampering construction of the Royal Courts of Justice. Unlike other historical structures, though, Temple Bar was saved from complete destruction. The stones weren’t carried off and used to build something else. They were saved, in hopes of a restoration. Nobody quite worked out how to do this, though.

Then, ten years later, at his wife’s instigation, Sir Henry Meux bought the 400 tons of stone from the Corporation of London and rebuilt Temple Bar as a gateway into his estate at

Theobalds Park

in Hertfordshire. Apparently, it did the trick of enhancing Lady Meux’s social status, as she’d hoped: It’s believed that she dined in its upper chamber with, among other notables, the Prince of Wales and Winston Churchill.

Then, ten years later, at his wife’s instigation, Sir Henry Meux bought the 400 tons of stone from the Corporation of London and rebuilt Temple Bar as a gateway into his estate at

Theobalds Park

in Hertfordshire. Apparently, it did the trick of enhancing Lady Meux’s social status, as she’d hoped: It’s believed that she dined in its upper chamber with, among other notables, the Prince of Wales and Winston Churchill.

Temple Bar remained at Theobolds Park until 2004, when it returned to London, to be reassembled, stone by stone, in Paternoster Square.

The History of Temple Bar site and the Wikipedia entry will offer you more details. I offer some pictures.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

Published on September 24, 2017 21:30

September 23, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of September 17, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Newly digitized to view on line: spectacular example of colonial calligraphy by a Boston writing teacher.

• Night witches, Nazi hunters, heroes: the women of Aviation Group 122.

• For a stylish Victorian lady, one's gloves must always be a shade lighter than one's dress.

• The confession of Mary Voce , who inspired George Eliot.

• Born to a one-time slave, Ruth Odom Bonner's life reflected America's "arc of progress."

• Image: Rachel M. Thompson & Catherine Jay Moore, early tech pioneers, from Radio Age, January 1924.

• Scientists once dressed frogs in tiny pants to study theories of reproduction.

• There never was a real 17thc Tulip Fever .

• Not seen, not heard: the Ladies' Gallery in the old Palace of Westminster.

• Theatrical cosmetics in the 19thc: making face, making "race."

• The Trotula: Women's Health Care in the Middle Ages.

• Explore Mary Wollstonecroft's legacy.

• Image: New acquisition by the Victoria & Albert Museum - Queen Victoria's sapphire and diamond crown , designed by Prince Albert.

• President Benjamin Harrison and the body-snatchers .

• The most inspiring hot-air balloon ride ever.

• A ditch runs through it: Robert Livingston and the first Erie Canal .

• Children of convicts transported to Australia grew to be taller than their peers in the UK.

• The fashion for white mourning .

• In the summer of 1792, a ferocious (and mysterious) beast terrorized the countryside around Milan.

• To read online - anonymous visual journal depicting an entire trip through West Indies in 1815.

• Image: Geta shoes made of solid iron and worn for martial arts training.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on September 23, 2017 14:00

September 21, 2017

Friday Video: The Gold Singing Bird Egg Basket

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:We Two Nerdy History Girls are partial to automata and other clockwork devices. Among numerous other marvels, I’ve shown you the singing bird pistols that inspired a scene for one of my novellas, and surviving clockwork items originally exhibited in London in 1807.

Susan has brought you—to name only two of many— a rope dancer and an automaton watch .

Searching the tags “scientific marvels” and “automaton” will bring up more posts on these ingenious devices.

Today, I offer you an egg.

Video: Gold Singing Bird Egg Basket from M.S. Rau Antiques

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on September 21, 2017 21:30

September 20, 2017

A Pair of Hand-stitched Handkerchiefs from the Wedding of Eliza Schuyler & Alexander Hamilton, 1780

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Most historical research for a novel involves words, and more words: letters, journals, diaries, and other books. But sometimes research means things: objects that were significant to my characters, and somehow survived: a tangible, magical link to the past.

Despite the popular history myths, 18thc women didn't sew the their all the clothing that their families wore. Nor did they shear the sheep and harvest the flax, process all the fibers, spin the thread, and weave the cloth; even if you lived on the edge of the wilderness, there were skilled tradespeople who took care of all that, and merchants ready to supply their wares at every price point. But while creating jackets, breeches, and gowns was left to tailors and mantua-makers, women did make the less challenging items like baby clothes, neckcloths, handkerchiefs, shirts, and shifts at home.

Sewing by hand was a useful skill, and considered a virtuously industrious one as well for women of every rank. But for many women, sewing was also a form of personal satisfaction and self-expression. The past (and the present!) is filled with women for whom sewing a neat, straight seam of perfectly even stitches or completing an intricate embroidery pattern is a matter of pride, accomplishment, and zen-like peace. Stitching for a special person could create a personal, even intimate, gift as well. Hand-made items can come with love and good wishes in every stitch.

Eliza Schuyler Hamilton (the heroine of my new historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton ) enjoyed sewing, embroidery, and knitting. I've already shared one surviving example of her needlework, this lavish embroidered mat to display the miniature of her then-fiancee, Alexander Hamilton, made during the summer and fall when they were engaged but apart. Here are a pair of handkerchiefs that, by family tradition, were also made by Eliza, and carried by her and Alexander at their wedding in December, 1780.

The larger handkerchief would have been Eliza's. Made of fine imported linen, it shows skilled cutwork over net inserts as well as precise stitching of the highest level, suitable for a special event like a wedding. (Given its size, I'm wondering if this might have been a neckerchief for wearing around the shoulders - a popular style in the 1780s - rather than a handkerchief, but since the archival description calls it a handkerchief, then so shall I.) Surviving, too, is the gentleman's handkerchief with an embroidered geometric pattern with floral accents. Again, the legend is that Eliza made the handkerchief for Alexander, a romantic gift that he must have treasured.

Today the linen on the two handkerchiefs is yellowed and so fragile that they cannot be unfolded, but the beauty and the undeniable care (and likely love) that went into each one of those long-ago stitches remains. The fact that both pieces were set aside and treasured for more than two hundred years shows how special they must have been - and even now, in their special, acid-proof archival box, they're still stored together.

Many thanks to Jennifer Lee, curator, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, for showing the neckerchief and the handkerchief to me.

Above: Pair of wedding handkerchiefs, c1780, Alexander Hamilton Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on September 20, 2017 21:00

A Pair of Hand-stitched Wedding Handkerchiefs, 1780

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Most historical research for a novel involves words, and more words: letters, journals, diaries, and other books. But sometimes research means things: objects that were significant to my characters, and somehow survived: a tangible, magical link to the past.

Despite the popular history myths, 18thc women didn't sew the their all the clothing that their families wore. Nor did they shear the sheep and harvest the flax, process all the fibers, spin the thread, and weave the cloth; even if you lived on the edge of the wilderness, there were skilled tradespeople who took care of all that, and merchants ready to supply their wares at every price point. But while creating jackets, breeches, and gowns was left to tailors and mantua-makers, women did make the less challenging items like baby clothes, neckcloths, handkerchiefs, shirts, and shifts at home.

Sewing by hand was a useful skill, and considered a virtuously industrious one as well for women of every rank. But for many women, sewing was also a form of personal satisfaction and self-expression. The past (and the present!) is filled with women for whom sewing a neat, straight seam of perfectly even stitches or completing an intricate embroidery pattern is a matter of pride, accomplishment, and zen-like peace. Stitching for a special person could create a personal, even intimate, gift as well. Hand-made items can come with love and good wishes in every stitch.

Eliza Schuyler Hamilton (the heroine of my new historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton ) enjoyed sewing, embroidery, and knitting. I've already shared one surviving example of her needlework, this lavish embroidered mat to display the miniature of her then-fiancee, Alexander Hamilton, made during the summer and fall when they were engaged but apart. Here are a pair of handkerchiefs that, by family tradition, were also made by Eliza, and carried by her and Alexander at their wedding in December, 1780.

The larger handkerchief would have been Eliza's. Made of fine imported linen, it shows skilled cutwork over net inserts as well as precise stitching of the highest level, suitable for a special event like a wedding. (Given its size, I'm wondering if this might have been a neckerchief for wearing around the shoulders - a popular style in the 1780s - rather than a handkerchief, but since the archival description calls it a handkerchief, then so shall I.) Surviving, too, is the gentleman's handkerchief with an embroidered geometric pattern with floral accents. Again, the legend is that Eliza made the handkerchief for Alexander, a romantic gift that he must have treasured.

Today the linen on the two handkerchiefs is yellowed and so fragile that they cannot be unfolded, but the beauty and the undeniable care (and likely love) that went into each one of those long-ago stitches remains. The fact that both pieces were set aside and treasured for more than two hundred years shows how special they must have been - and even now, in their special, acid-proof archival box, they're still stored together.

Many thanks to Jennifer Lee, curator, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, for showing the neckerchief and the handkerchief to me.

Above: Pair of wedding handkerchiefs, c1780, Alexander Hamilton Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on September 20, 2017 21:00

September 19, 2017

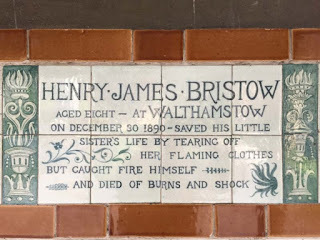

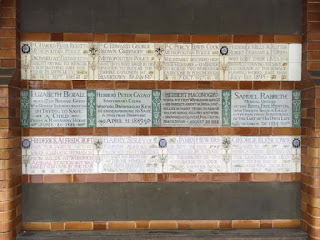

The Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Before we embarked on our month-long stay in London, I had read about the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice in Postman’s Park , and put it on my (very long) list of places to see. This is why, following our visit to the Museum of London one day, my husband and I walked a short distance to quiet little Postman’s Park, for a completely different kind of experience of history.

The monuments for fallen military men, for political and military leaders, are easily found elsewhere. This memorial was meant for ordinary people who gave their lives to save others.

It was the idea of G.F. Watts, a Victorian painter and sculptor, to memorialize everyday heroes. His plan was for over a hundred ceramic plaques with the heroes’ names and their brave acts, but the memorial opened in 1900 with only four, and today seems to have stopped at fifty-four, though it appears that names will continue to be added over time.

Even fifty-four, though, provide for a powerful experience. And it does grows heartbreaking, reading one brief, sad story after another. Still, there's something consoling, too, especially in times like ours, when there seems to be so much ill will in our world. The names on the tablets remind us that the best in human nature does triumph, and does so often. These tablets stand for countless unnamed everyday heroes who have acted unselfishly over the years. There are some, we can be sure, who are acting heroically at this very moment.

You can move through a 3D image here , view large images here, and see examples of more detailed histories here at the Smithsonian site. Wikipedia provides a list of the tablets here .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on September 19, 2017 21:30

September 18, 2017

Writing Away From Home, c1780

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,I'm a wandering writer. I don't have a desktop computer, or even a desk, let alone an office. Perhaps because I scribbled away at my first books on legal pads on commuter trains and while waiting at kids' sports practices, I can (well, most of the time) write wherever and whenever. With a laptop computer, it's easy enough, and even if that's not with me, I always have my smartphone for notes and ideas.

It wasn't that way in 18thc America. The painting, left, is an illustration by Angelica Kauffman to one of the most popular novels of the 1780s: Emma Corbett, or, The Miseries of Civil War founded on Some Recent Circumstances which happened in America. The civil war in question was the American Revolution, and when Samuel Jackson Pratt published his novel in 1780, the "miseries" were real and current. Told in letters, the story concerns the tragedies faced by two families torn apart by the war - the first fictional work to describe both sides of the conflict.

Here one of the novel's young women, Louisa Hammond, is shown writing a letter outdoors. While this makes for an elegant illustration, it also demonstrates the challenges of writing away from home. Writing on a single sheet of paper and using her portfolio, balanced on her knee, as an impromptu desk, Louisa holds an open bottle of ink in one hand, ready to dip her feather pen repeatedly as needed. Writing with an open bottle of ink seems a perilous act in a white dress. If the faithful dog at Louisa's feet is suddenly startled, or a breeze catches her hat and startles her, then there's a good chance that ink is going to splatter across her embroidered apron.

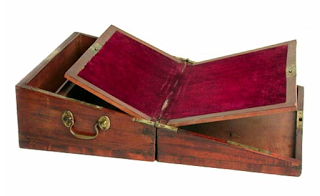

But while Louisa Hammond is a fictitious character, real people found a way to write away from home, too. Most gentlemen who traveled frequently owned a portable desk. Basically a hinged wooden box, these desks were the predecessors of modern laptop. Designs varied to taste, but all have a surface covered in soft cloth (which made a quill pen move more easily over the page) for writing, plus compartments for storing bottles of ink, pens, paper, and other supplies. The desks folded and latched shut into a self-contained unit for carrying.

This desk belonged to Alexander Hamilton, a real-life officer (unlike Louisa Hammond's true love) in the Continental Army who did survive the American Revolution. In the 1780s and after the war, Hamilton worked as a lawyer, frequently traveling by horseback and carriage for various cases around the state of New York. During this time, he also served as a representative to the Continental Congress and as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, which meant more traveling between his home in New York City and, most often, Philadelphia - hundreds of miles on unpredictable roads, in good weather and bad.

Hamilton was a ferociously prolific writer, full of ideas, opinions, and arguments, and blessed with the gift for words to express them. In an era before phones, being able to communicate through letters was vital. Wherever Hamilton went, this desk usually accompanied him. Made of Spanish mahogany with brass hinges, the desk is battered and well-worn from use.

Tradition says that this was the desk on which Hamilton wrote the fifty-one essays that became his share of The Federalist Papers, and helped lead to the ratification of the Constitution. Striving to remove himself from the distractions of New York City in 1787, Hamilton and his wife Eliza traveled by packet up the Hudson River to Albany and The Pastures, the home of Eliza's family, the Schuylers. The length of the voyage was dependent on winds and currents, yet it must have given him uninterrupted days to think and write - something every writer craves.

Still, spoiled as I am by modern technology, I marvel at the idea of writing this way: drawing each letter, each word, with a quill pen in one hand and an ink bottle in the other, on a desk like this braced against your knees or a rickety ship-board bunk, and everything (including you) rocking and shifting as the packet tacked back and forth across the river....

Upper left: Louisa Hammond by Angelica Kauffman, c1780s, Fitzwilliam Museum Collection.

Right and lower left: Portable desk owned by Alexander Hamilton, American or English, late 18thc. Collection of Department of Special Collections, Burke Library, Hamilton College. Right photo courtesy of New-York Historical Society. Lower left photo ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

I, Eliza Hamilton will be published by Kensington Books on September 26, 2017. See here for more information and to pre-order.

Published on September 18, 2017 21:00

September 16, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of September 11, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• A bibliophile's guide to National Park libraries in America.

• John Hancock's table : turtles, pineapples, and the paradoxical politics of 1768.

• An Irish suffrage leader tours America in 1917.

• Heartbreaking keepsake book made by a Jewish teen in 1941 for his boyfriend before he was murdered at Auschwitz.

• Amazing librarians : the women who rode miles on horseback to deliver library books.

• Image: "The ' New Woman " and her Bicycle" Puck Magazine, 1895.

• How an 18thc orange-flavored dessert recipe created a modern political maelstrom.

• What does that say? Deciphering 17th-18thc handwriting .

• Ten common phrases that originated in the middle ages.

• Newly digitized: Gertrude Bell's 1911 diary of her journey from Damascus to Aleppo via Baghdad.

• America's first planetarium holds the ultimate cabinet of curiosities.

• The Roman cemetery where Keats, Shelley, and other unfortunate international visitors are buried.

• Image: This hairy beast is an 18thc man's muff .

• An elegant, be-ribboned 1870s dress with a watery history.

• Why was Benjamin Franklin estranged from his wife for nearly two decades?

• The history of the ampersand .

• A well-worn pair of men's striped trousers , dating from the 12th-14thc.

• Seven flavors that any solider of the American Civil War would recognize.

• This is what an 18thc feminist looked like.

• Video: Just for fun: What happens when you fasten a GoPro camera on the blades of a windmill .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on September 16, 2017 14:00