Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 31

August 5, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of July 31, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Everything you've ever heard about chastity belts is a lie.

• Joys and sorrows: Lewis Hine at Ellis Island.

• Sketches from a journey across Europe in 1817.

• So how many miles in a month did the old wool spinners cover with a walking wheel ?

• The truth about John Quincy Adams' skinny-dipping and reporter Anne Royall .

• Did the invention of the sewing machine mean liberation or drudgery for 19thc women?

• Image: Witnesses: three chestnut trees at Hougoumont bear musket ball scars that prove they were there in 1815.

• On-line exhibition: Victorian Valentines : Intimacy in the Industrial Age.

• Mapping Dante's Inferno , one circle of hell at a time.

• America's first woman doctor, Elizabeth Blackwell.

• Image: Navigate your way around the Roman city of Londinium c AD50 with this interactive map.

• Fashion's attics : in Italy, designers maintain their own archives both for preservation and inspiration.

• " Picturing Places ", a new online resource from the British Library, helps to visualize the Georgian past with images from their collection.

• Benjamin Franklin's London.

• Image: Medieval Italian colored glass drinking horns .

• What Shakespeare's house looked like in 1737.

• The lost young love of John Quincy Adams .

• Did Jane Austen develop cataracts from arsenic poisoning?

• Over 120 years later, this garden of glass flowers is still blooming.

• Image: Just for fun - the cover of Enlightened Bride magazine.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on August 05, 2017 15:00

Shameless Self-Promotion: Read the First Chapter to I, ELIZA HAMILTON

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Later this week, my publisher, Kensington Books, will post the first chapter to my new historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton , on line.

But subscribers to my mailing list are reading it now - and you can, too. Simply click here to join my mailing list and you'll be sent an instant link to the preview. I promise your information won't be shared with anyone else, nor will I fill your inbox to overflowing. You'll only hear from me perhaps 2-3 times a year with important news or offers, and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

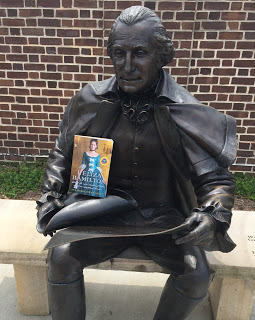

Hey, even George Washington has HIS copy....

Published on August 05, 2017 14:05

August 3, 2017

From the Archives: A Glimpse into the Edwardian Past

Susan reporting:

This isn't a single video, but a series of short, silent clips pieced together. The description notes that it's also been "enhanced," with the focus sharpened and the speed made consistent. That said, it's a wonderful slice of Edwardian life, a medley of street scenes, factory-dominated landscapes, amusement parks, family scenes, dockside farewells, and holidays at the beach. The caption on YouTube says the clips were mostly shot in London, with some perhaps from Cork, Ireland as well.

Much like one of our earlier Friday videos from 1895, the people here may have been arranged before the camera, but no one is acting. Seeing how everyone walks, how their clothes move and how they carry themselves, the carriages and wagons and early motor cars - it's as close as we'll get to being able to look backwards in time more than a hundred years.

Several things stood out to me while watching this:

1) Everyone dressed much more formally then, no matter what the occasion.

2) Boys and men have always been willing to stick their faces in front of a camera.

3) Wherever the people in the last scene are, it's an incredibly happy crowd. So many smiles!

4) The women's hats are fantastic, and so are the men's moustaches.

What do you notice?

If you receive this post via email, you may be seeing only black box or empty space where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on August 03, 2017 21:00

August 2, 2017

Fashions for August 1852

August 1852 fashions

August 1852 fashions

August 1852 fashion description

Loretta reports:

August 1852 fashion description

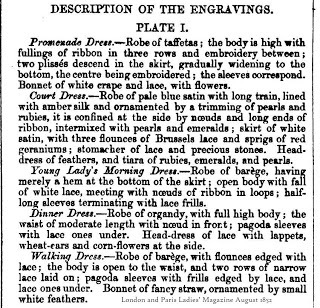

Loretta reports:Last year, in my 1850s fashion post , I lamented the dearth of complete magazines, with fashion plates, online for the Victorian era. It seemed that Godey’s was about all there was, with one or two Petersons. Since then, I’ve found a nice collection of the London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion on Google Books. The magazine is rich in fashion prints. For August 1852, I chose Plate 1 because it shows a court dress, which tends to be quite a different fashion species from other clothing, even evening dress. While the plumes tend to give it away, court dress also stands out in prints like these because it’s so elaborate. This one is clearly so, dripping with jewels.

Plissé refers to fabric with a pleated or puckered finish . Interestingly, the Merriam- Webster dictionary lists a “first known use” of the term in 1859,” yet here it is in 1852. I’ve had this same experience many times, finding earlier usages in 19th century books online than the OED or M-W list.

Barège is a thin fabric made of silk and cotton or wool.

To compare and contrast actual dresses with prints, you might want to look at some early 1850s fashions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s online costume collection here , here , and here .

Images from The London and Paris Ladies' Magazine of Fashion , ed. by Mrs. Edward Thomas, via Google Books.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 02, 2017 21:30

July 31, 2017

Seeing the Emotion in the Words of a Handwritten Letter, 1797

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,One of the most challenging aspects of writing historical fiction is trying to remove all the fusty layers of time and interpretation to capture the immediacy of the past. Whenever possible, I look to primary sources - letters, diaries, journals - that give voices to long-gone people. Seeing those original words reprinted in a book or on-line is useful, of course, but being able to see the originals of those same letters can take research - and inspiration - to an entirely different level.

Earlier this year, I was fortunate to see first-hand one of Abigail Adams' more famous (or more infamous, depending on your perspective) letters now in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Abigail was no fan of Alexander Hamilton, nor was her husband, John Adams. As young as the American republic was in1797, vitriol, name-calling, and backstabbing were already part of the political system, and there were few rivalries more bitter than the one between Hamilton and Adams. Each had many reasons, and both were right: Hamilton believed he'd been shut out of the government he'd help create during George Washington's presidency, while Adams felt that Hamilton had undermined his attempts to win a second presidential term himself. Each accused the other of unseemly ambition, and both were justified there, too.

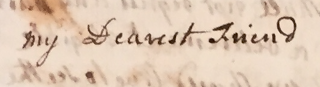

As can be expected, Abigail supported her husband, and loathed Hamilton. The Adamses had always been frank in writing to one another about politics, and her (low) estimation of Hamilton echoed his own. The letter that she wrote in late January, 1797, begins calmly enough, with notes of the weather and the "pain and anxiety of Seperation." Then she launches into gossip she'd heard regarding Hamilton, followed by her own appraisal of his character, only to realize at the letter's end what she's written:

"Mr. Black told me the other day on his return... that Col. H[amilton] was loosing ground with his Friends in Boston. On what account I inquired. Why for the part he is said to have acted in the late Election. Aya, what was that? Why, they say that he tried to keep out both Mr. A[dams] and J[efferson], and that he behaved with great duplicity....that he might himself be the dictator. So you see according to the old adage, Murder will out. I despise a Janus....it is my firm belief that if the people had not been imposed upon by false reports and misrepresentations, the vote would have been nearly unanimous. [Hamilton] dared not risk his popularity to come out openly in opposition, but he went secretly cunningly as he thought to work....

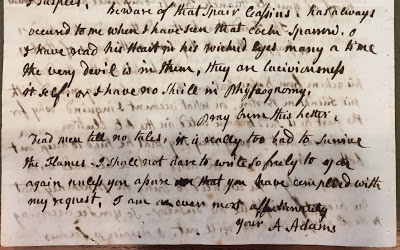

"Beware of that spair Cassius, has always occured to me when I have seen that cock sparrow. O I have read his Heart in his wicked Eyes many a time. The very devil is in them. They are laciviousness itself, or I have no skill in Physiognomy.

"Pray burn this Letter. Dead Men tell no tales. It is really too bad to survive the Flames. I shall not dare to write so freely to you again unless you assure that you have complied with my request."

Obviously, John Adams didn't obey Abigail's request. Read as transcribed here, her words are indeed "bad," but to see them as she wrote them in the original letters showed exactly how angry she was.

Compare the delicacy of Abigail's greeting in the same letter, right, with the closing paragraphs, lower left. (As always, please click on the image to enlarge.) By the time she reached "Beware of that spair Cassius..." she was driving the pen across the page, her letters growing darker, wider, and less formed as she pressed the nib of her pen furiously across the paper. How much more powerful - and revealing - those words are in their handwritten version!

Many thanks to Sara Georgini, Historian and Series Editor, Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, for showing this letter and others to me. Excerpt from letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, January 28, 1797, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Above left: Abigail Adams by Jane Stuart (after Gilbert Stuart), c1800, Adams National Historic Park.

Right & lower left: Excerpt from letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, January 28, 1797, Massachusetts Historical Society. Photo by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on July 31, 2017 21:00

July 30, 2017

Octavia Hill, Victorian Social Reformer

Sargent, Octavia Hill 1898

Loretta reports:

Sargent, Octavia Hill 1898

Loretta reports:In the course of our stay in London, we took a number of guided walks, during which I discovered dozens of interesting people, including several intrepid women.

Our Old Marylebone Walk (which propelled us to the Wallace Collection in very short order), introduced me to, among others, Octavia Hill. She was a social reformer whose work puts her in a class, I think, with Florence Nightingale. You can read a detailed biography of her here at Wikipedia , and some of her writing here .

Having written about the Ragged Schools in Dukes Prefer Blondes , I was, naturally, intrigued to learn she’d started her work by making toys for Ragged School children. But I was more impressed by her ability to get things done. Like so many Victorian reformers, she had, apparently, a will of iron—a necessary character trait, although not necessarily one that endears a person to everybody. Still, she got things going, and by all accounts, her houses were successful.

But social housing wasn’t her only achievement. Believing that city workers should have access to green spaces, she campaigned to save several suburban woodlands from development. And while she may have been shortsighted about women’s suffrage and other social reforms, the heart of her work lives on, in the National Trust and various housing organizations, in the U.K. and the U.S.

You can read more about her here .

Image: John Singer Sargent, Octavia Hill , 1898

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on July 30, 2017 21:30

July 29, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of July 24, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Heels, flats, and ankle straps: shoes in Jane Austen's world.

• Gorgeous memento of a forbidden love: the Maria Fitzherbert jewel.

• The Witch of Berkeley meets the Devil, and medieval hilarity ensues.

• Herbal folk cures from County Donegal.

• What did a "Welsh comb" mean to 18thc men (and why blame the Welsh?)

• Image: The gold rosary Mary Queen of Scots carried to her execution.

• Washington's Wormley Hotel , the premier late-19thc gathering place for politics, diplomacy, and social elegance.

• No "King of Kings": how and why American revolutionaries changed the Book of Common Praye r.

• Capitol ghosts .

• Removing the Dauphin from his mother, Marie Antoinette .

• India's lost historic "party mansions."

• Why you can't ever call an enslaved woman a "mistress."

• Image: Some Anglo-Saxon women wore crystal balls on their belts -amulets of the sun and purity, but their true meaning is a mystery.

• Fifteen rare color photographs from World War II.

• Virtual " unrolling " of ancient scroll buried by Vesuvius reveals early text.

• Liberty Poles and the two American Revolutions.

• The mystery of Sappho .

• History is the intersection of what actually happened and how we perceive it.

• Letters written to loved ones after Gettysburg reveal the pain of those left behind.

• Food photography over the years.

• Martha Gunn , 18thc Brighton celebrity and "dipper."

• A Roman glass bowl that was imported to Japan - in the 5thc.

• Image: Just for fun: Gloria Gaynor's iconic "I Will Survive " as a Shakespearean sonnet.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on July 29, 2017 14:00

July 23, 2017

Still Fishin'

Our fishin' trip continues - but never fear, we'll be returning to blogging next week with a fresh batch of Breakfast Links, and new posts to follow.

Our fishin' trip continues - but never fear, we'll be returning to blogging next week with a fresh batch of Breakfast Links, and new posts to follow.In the meantime, we invite you to explore our individual blogs for much more about our books and the stories, history, and research behind them:

Loretta's author blog .

Susan's author blog .

See you next week!

Left: Fishing by Daniel Ridgway Knight, c1890, private collection

Published on July 23, 2017 14:42

July 13, 2017

Gone Fishin'

It's the middle of July, and we feel a bit of fishin' is in order.

It's the middle of July, and we feel a bit of fishin' is in order. Loretta is continuing on her Grand Tour abroad, and Susan is heading off to the 18thc and Colonial Williamsburg. Seems like as good a time as any to take a short break from blogging and general social media-ing. Look for us to return later this month.

Enjoy your summer!

Elegant Ladies Fishing by Georges-Jules-Victor Clarin, c1900. Image via Sotheby's.

Published on July 13, 2017 21:00

July 12, 2017

The "Art & Mystery" of Cutting an 18thc Gown

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,An 18thc mantua-maker (dressmaker) seldom shared the "art and mysteries" of her trade with her customers. It was hard-earned knowledge and skill, gained through an apprenticeship that might have lasted seven years, and it also benefited the business to keep a bit of alluring, magical mystery to her fashionable creations.

For the last five years, Sarah Woodyard, journey-woman in the mantua-making trade, Margaret Hunter Shop at Colonial Williamsburg (shown here in the floral short gown), has been studying different theories of cutting out 18thc gowns - the most important part of the "art and mystery" of dressmaking - and has agreed to share some of her research here.

There was, of course, no single way of cutting out an 18thc gown. Various mantua-makers would have devised methods that worked best for them, and even at the Margaret Hunter Shop, each mantua-maker has a favorite technique. However, Sarah's study of extant garments made her realize the importance of the linen linings in construction and fittings and, in best 18thc style, led her to develop her own favorite method. The technique is simple. Using linen, a less expensive fabric, the lining is cut out and used to establish the fit of the bodice and to "build' the outer garment on top of the lining. The lining becomes both the guide for the creation the gown, and the base for its structure. Not only would this method preserve the more costly outer fabric from being damaged by a slap-dash cutting mistake, but it was also an easier way to control the large amounts of fabric that created the volume of a sack or common gown.

The technique was also a time-saver for both a busy customer, and a mantua-maker determined to make the most of her sewing time. At every price point, women's clothing in the 18thc was fitted and cut on the individual body rather than on a dressmaker's form, ensuring a custom fit. By fitting just the lining on the customer, the rest of the gown could be cut and stitched without her presence until one more final fitting.

In these photographs, Sarah is shown fitting the plain linen lining for a polonaise jacket and matching petticoat on Aislinn Lewis, one of the blacksmiths at Colonial Williamsburg. This ensemble was one of Sarah's final apprenticeship projects completed to prover her skill and move up as a journey-woman. Sarah only required Aislinn for a fitting in the morning to cut the lining, and another in the afternoon for a sleeve fitting. That was all; Sarah was able to hand-sew and complete both pieces - made from pink changeable silk - in about thirty-six hours, including all the trimmings.

The same technique could be used to construct a gown for a woman unable to come in person to the mantua-maker's shop. For women who lived far from town, travel could be prohibitively difficult, and in many families the men traveled to town on business, while the women remained at home with the children.

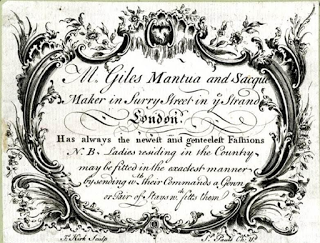

The trade card, bottom right, for London mantua-maker M. Giles offers the same services for "Ladies residing in the Country [who] may be fitted in the exactest manner by sending with their Commands a Gown or Pair of Stays which fitts them."

As the advertisement shows, a woman could still have new clothing made by sending either an existing gown or a pair of stays to her mantua-maker. Stays were the 18thc version of a corset; no only were they, too, custom-fitted, but over time they assumed the shape of the wearer's body, and could serve as a good replica of her upper torso. Either way, the mantua-maker could use the existing garment to copy and cut a new lining as a pattern, and built a new gown from the lining out without an in-person fitting - and once again, fashion triumphed.

As the advertisement shows, a woman could still have new clothing made by sending either an existing gown or a pair of stays to her mantua-maker. Stays were the 18thc version of a corset; no only were they, too, custom-fitted, but over time they assumed the shape of the wearer's body, and could serve as a good replica of her upper torso. Either way, the mantua-maker could use the existing garment to copy and cut a new lining as a pattern, and built a new gown from the lining out without an in-person fitting - and once again, fashion triumphed.All photographs by Fred Blystone. Used with permission.

Trade card, 1770s, London, British Museum.

Published on July 12, 2017 21:00