Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 65

January 17, 2016

Bedroom furnishings, early 1800s

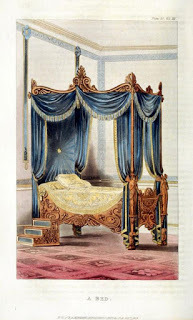

Grecian style bed 1828

Grecian style bed 1828

Loretta reports:

Continuing my visual guide to Dukes Prefer Blondes *, I’m taking you into my heroine’s bedroom to look at a couple of its furnishings.

“The bed was a modern one in the Grecian style, with bare-breasted females supporting the bedposts. Apt enough. Lady Clara ought to have a pair of caryatids at the foot of the bed, guarding the goddess’s temple. Other Grecian-style articles looked on from the mantelpiece. An elaborate urn clock dominated the center. Cupid stood on its pedestal, pointing to the time on the revolving band encircling the urn.”—Dukes Prefer Blondes

This bed in Ackermann’s Repository for October 1828 was my inspiration.

Grecian style bed description

As to the clock: I was looking through Eric Bruton’s fascinating

History of Clocks & Watches

** when I came upon this lovely timekeeper from the late 1700s. According to the book, it’s in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague—unfortunately, closed, from what I could ascertain during my online search for a sharper image.

Grecian style bed description

As to the clock: I was looking through Eric Bruton’s fascinating

History of Clocks & Watches

** when I came upon this lovely timekeeper from the late 1700s. According to the book, it’s in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague—unfortunately, closed, from what I could ascertain during my online search for a sharper image.

I found other annular clocks online, most from a later period.

This from c.1900 .

This French 1850s one .

This one from the 1880s.

And this.

*Previous posts here and here and here and here .

**My 1989 edition of this wonderful book has provided inspiration for other watches and clocks in my stories, most notably the naughty pocket watch in Lord of Scoundrels .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 17, 2016 21:30

January 16, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of January 11, 2016

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, blogs, articles, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, blogs, articles, and images via Twitter.• Shop windows : the drapery trade in the long 19thc.

• How the naming of clouds changed the skies of art.

• What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

• The beginning of the women's health and fitness industry: the fit flapper of the 1920s.

• Image: This is fantastic! Women prospectors on their way to the Klondike, 1898.

• Jane Austen's copied music manuscripts now available online.

• Flower power: two stunning 18thc gentlemen's waistcoats .

• Image: Beautiful penmanship for this 17thc recipe for a lemon biscuit .

• Pet rabbits in 19thc literature and history.

• Sobering: nearly every historic fruit and vegetable once found in the United States has disappeared.

• Sir John Falstaff , the notorious highwayman.

• Where the statues of Paris were sent to die.

• Image: A beautiful pair from the Fashion Museum in Bath: a fashion doll's mantua and a woman's court mantua, both from the 1760s.

• Oak Hall ready to wear menswear , c1902 - what a dapper clerk with the measuring tape around his neck!

• In 1942, the Hershey Hotel was a chocolate-scented POW camp .

• What do Thomas More, Hans Sloane, and a Moravian burying ground have to do with one another?

• A Roman ruin at the hairdresser.

• Image: Silver "Jailed for Freedom" pin that belonged to activist Alice Paul.

• An 1830s cream-colored silk dress - that likely isn't a wedding dress.

• Explore the contents of a 17thc bookshop , recreated from the bookseller's will and inventory.

• Ten abandoned places and ghost towns in Florida.

• In honor of the young men whose Movember efforts weren't quite up to snuff: The Lay of the Red Moustache , 1851.

• Dr. G. Zander's medico-mechanical gymnastics .

• Just for fun: Tudor Tinder .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on January 16, 2016 14:00

January 14, 2016

Horse-Drawn Carriages in Motion

Cabriolet

Loretta reports:

Cabriolet

Loretta reports:The heroine of Dukes Prefer Blondes drives her own vehicle—a cabriolet, as pictured at left— and there's quite a bit of traveling in the story, in various kinds of vehicles, including the hackney cabs and coaches I recently described .

This short video offers s a chance to watch horses and carriages in action. Note that many of the vehicles are earlier than the time of my story, and some are quite modern, made specially for extreme carriage racing.

Image: John Ferneley, William Massey-Stanley Driving His Cabriolet in Hyde Park 1833, courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on January 14, 2016 21:30

January 13, 2016

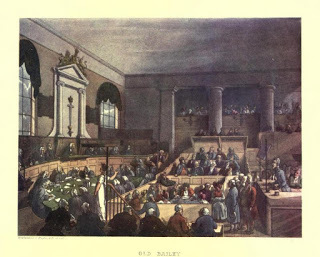

How Many Handsewn Stitches in an 18thc Man's Shirt?

Isabella reporting,

In the 18thc, a man's linen shirt was perhaps the most democratic of garments. Every male wore one, from the King of England to his lowest subjects in the almshouse, and though the quality of the linen and laundering varied widely, the construction was virtually the same.

Contrary to the modern belief that the people of the past were dirty slobs (a bugaboo we NHG are always trying to banish), Georgian men were fastidious about their shirts. Men were judged by the cleanliness of their linen. From laundry records of the time, it's clear that the majority of men changed their shirts daily, and in the hot summer months, it wasn't unusual to change twice a day . This wasn't just a habit of wealthy gentlemen, either. Tradesmen, shopkeepers, and others of the "middling sort" had a good supply of shirts in their wardrobes, a dozen or so on average.

While most of these shirts were purchased from tailors, shirts were one of the few garments that women could make at home for their husbands, brothers, fathers, and sons. Eighteenth century shirts were loose-fitting, geometric garments, all precise squares and rectangles with straight seams. They weren't difficult for the average seamstress to construct - keeping in mind that everything was being sewn by hand before the invention of the sewing machine. The precision of that seamstress's stitching would make them not only more attractive, but also more long-wearing through the rough-and-tumble laundering (no gentle cycle) of the time. But how long would it take to make such a shirt? And how many stitches must be taken in the process?

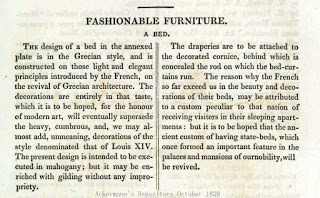

When I was visiting the Margaret Hunter millinery shop in Colonial Williamsburg last month, the mantua-makers (whose seamstresses can make men's shirts just as readily as the tailors) were pondering this exact question. A chart in the July, 1782 issue of The Lady's Magazine, right, calculated the "number of stitches in a plain-shirt", perhaps to provide the amateur seamstresses among their readers with a number to impress the home-stitched shirt's wearer. The Magazine's estimated total was an impressive 20,619 stitches for a man's shirt.

The Margaret Hunter seamstresses took these calculations a step further. Working an average of 30 stitches per minute at a gauge of 10 stitches per inch, it would take approximately eleven and a half hours to stitch a shirt. Of course that doesn't take into account the time for cutting threads, finishing a thread, or threading needles, nor for cutting out the pieces to be sewn, and it also doesn't make allowances for the individual seamstress's speed. While the needles in the Margaret Hunter shop seem to fly, the ladies freely admit that they'd probably be considered slow in comparison to their 18thc counterparts who sewed from childhood.

More about 18thc shirts here and here. Many thanks to Janea Whitacre, mistress of the mantua-making trade, Colonial Williamsburg, for her assistance with this post.

Left: Shirt, maker unknown, linen, probably made in America, c1790-1820. Winterthur Museum.

Photograph © 2014 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Below: Excerpt from The Lady's Magazine, July, 1782.

Published on January 13, 2016 21:00

January 11, 2016

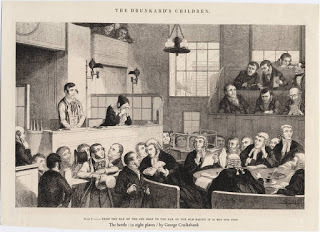

The Old Bailey

Rowlandson, “The Old Bailey

”Loretta reports:

Rowlandson, “The Old Bailey

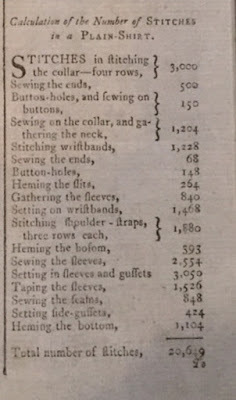

”Loretta reports:Several scenes in Dukes Prefer Blondes occur in or around the Old Bailey. Since it’s rather different now from what it was in the early 1800s, I highly recommend that Nerdy History Persons visit the Proceedings of the Old Bailey online , where I researched not only the building and environs, but my criminals and court cases.

From the intro to the building's history:

“The Old Bailey, also known as Justice Hall, the Sessions House, and the Central Criminal Court, was named after the street in which it was located, just off Newgate Street and next to Newgate Prison, in the western part of the City of London. Over the centuries the building has been periodically remodelled and rebuilt in ways which both reflected and influenced the changing ways trials were carried out and reported.”You can read more about its evolution here , as well as pinpoint the Sessions House (where trials were held) and Newgate Prison, conveniently located next door.

The color image above of an Old Bailey trial is a couple of decades before the time of the story, but according to the website, the “basic design of the courtroom remained the same.”

Here’s an interesting historical detail from the Old Bailey site :

“Before the introduction of gas lighting in the early nineteenth century a mirrored reflector was placed above the bar, in order to reflect light from the windows onto the faces of the accused. This allowed the court to examine their facial expressions assess the validity of their testimony. In addition, a sounding board was placed over their heads in order to amplify their voices.”

By the time of the George Cruikshank illustration of 1848, the gas lights were in and the reflector was gone—although I’d think they could still use the sounding board.

Images:

Thomas Rowlandson, “The Old Bailey,” from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London, Vol 2, courtesy Internet Archive.

George Cruikshank, “ From the bar of the gin shop to the bar of the Old Bailey it is but one step ,” from The Drunkard’s Children (1848), Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 11, 2016 21:30

January 10, 2016

Shame: "After the Misdeed", c1885

Isabella reporting,

Although Loretta and I live hundreds of miles apart, we often (very often) talk on the phone, and one of our recent conversations centered on how frequently shamed and fallen women appear in 19thc art and literature.

The reasons for this are, of course, so many and varied that I can't possibly address them all successfully in a mere blog post. (The Foundling Museum in London recently held and exhibition devoted to the myth and reality of The Fallen Woman, and the exhibition's web site still has a number of good links to explore here .) The morality of the time was behind much of it. The perceived "frailty" of women and the need for them to be protected by Good Men, husbands, fathers, and brother, also meant that women were equally susceptible to unfortunate choices, seduction, and ruin at the hands of Bad Men.

In art (if not in life), the women who became fallen were usually young and beautiful, adding a salacious edge to the tragic morality tale. Not surprisingly, the Bad Man - the rake, the bounder, the seducer - rarely merits a painting of his own.

All of which led Loretta and me to this beautifully dramatic painting. (As always, click on the image to enlarge it.) The artist is a Frenchman, Jean Béraud (1849-1935), who was a contemporary and friend of the Impressionists, and best known at the time for his scenes of Belle Epoque Paris. But he also painted his share of genre and morality pictures. His most over-the-top one is St. Mary Magdalene in the House of Simon the Pharisee, which introduces both Jesus Christ and a well-corseted and repentant Mary Magdalen into a group of wealthy 19thc Frenchmen; I particularly like the unimpressed fellow lighting his cigar to the left.

By comparison, After the Misdeed is subdued. The woman's pose, her face buried in shame against the sofa, leave no doubt that she's sinned. Nineteenth century viewers would be certain that the misdeed she'd just committed must be sexual. Her beautifully fashionable clothing could either show that she's a well-bred lady who has wandered - a pampered daughter rejecting a proper suitor for a cad, or an adulterous wife, instantly filled with regret? Or is she a demi-mondaine, a woman who sold her virtue in return for that elegant fur tippet and bustled dress? The lush red velvet sofa could also represent luxurious excess, a symbol of the woman succumbing to passion.

But Loretta and I aren't 19thc gallery-goers. Despite being Nerdy History Girls, we're firmly in the 21stc, and we couldn't resist considering less momentous possibilities for After the Misdeed. Did this distraught lady arrive at a party where the hostess wore the same dress? Did she use the wrong fork at dinner? Did she leave the parlor door open so that the family dog made a mess on that velvet sofa?

What would you guess her misdeed to be?

Above: After the Misdeed by Jean Béraud, c1885-90, National Gallery, London.

Published on January 10, 2016 17:00

January 9, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of January 4, 2016

Happy new year! We're back with a fresh round of Breakfast Links for you - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, blogs, articles, and images via Twitter.

Happy new year! We're back with a fresh round of Breakfast Links for you - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, blogs, articles, and images via Twitter.• Hypnotic GIFs of Victorian optical toys .

• London's oldest theatrical tradition involves eating cake .

• "Stand fast in the liberty": a very rare 18thc. waistcoat belt .

• How did women in the past cope with their periods ? Another view here .

• A walk through 1873 London (and earlier) by way of Walter Thornbury's illustrations.

• The mysterious seaweed tunnel of Pegwell Bay, Kent.

• Image: Skating on the Serpentine , 1839.

• A dangerous freedom for unmarried women: Anthony Trollope, pillar post boxes, and love letters.

• How did people sleep in the middle ages?

• "No stimulating drinks ": Thomas Jefferson lays out guidelines for students at University of Virginia, 1819.

• A fiercely festive feline from Egypt, 6th-7thc BC.

• Image: Perfect title of an 18thc novel (with a ton of spoilers.)

• Because you never know when you might NEED to know: vintage user's manual for operating Disneyland's monorail .

• An unsolved 1920s murder case : the mystery of Annie Hearn's sandwiches.

• Not too late: how to make cuneiform gingerbread cookies for the new year.

• Image: A little medieval humor from the Abbey of Sainte Foy.

• Buried under a boulder: the grave of a Lancashire " witch ."

• The morning after the night before: detoxing in history.

• Image: An 18thc back-scratcher .

• Why the 1960s were swinging (at least fashion-wise.)

• An 1860s acrobat's special corset for "flying."

• A c1800 book to read online, with advice for every kind of lover: The Complete Art of Writing Love-Letters .

• Old Judy, keeper of the Newcastle Upon Tyne town hutch .

• Image: Martha Washington wore these shoes for her 1759 wedding to George.

• Why is the Flying Scotsman so famous?

• Not historical, but still breathtaking: traffic camera catches snowy owl in flight.

• Just for fun: the V&A lets you design your own over-the-top 18thc. wig.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on January 09, 2016 14:00

January 7, 2016

Friday Video: An 18thc Automaton Watch

Isabella reporting,

This is a very short video - less than a minute - but it's still an impressive tribute to the level of craftsmanship of 18thc. jewelers and watchmakers. Made of gold with enamel, the watch's artistic detail is as stunning as the clockwork mechanism that animates it. Alas, both the maker and the original owner's name are now forgotten, and today the watch is most famous for having been in the collection of King Farouk of Egypt during the 20thc.

But it's easy to imagine some wealthy (for a watch like this would have been a very costly bauble) nobleman easing this from the fob pocket of his silk breeches and ostentatiously checking the time, making sure that all around him saw the tiny country miss swinging back and forth from the dial. Click on the photo right to see all the details. Beautiful!

Automaton watch, quarter repeater, gold and enamel, late 18thc. Shaw Watch Collection, Guernsey Museums & Galleries.

Published on January 07, 2016 21:00

January 6, 2016

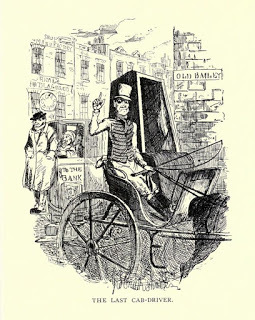

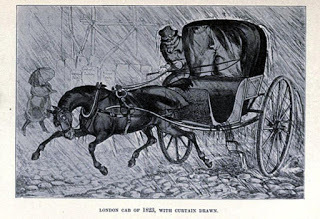

Hackney Cab vs. Hackney Coach

Cruikshank, “The Last Cabdriver"

Cruikshank, “The Last Cabdriver"

Loretta reports:

My characters in Dukes Prefer Blondes spend time in hackney coaches and hackney cabs. You will often find the terms used interchangeably, as though they were the same thing. However, a hackney cab was quite a different article from a hackney coach. The cab was a two-wheeled, one-horse vehicle. It held only two passengers, and seemed to be generally regarded as a mode of transportation for those who liked to live dangerously.

Leigh’s New Picture of London for 1834 briefly explains the difference here . You can read about them here in Omnibuses and Cabs, Their Origin and History , which includes excerpts from Dickens’s lively descriptions.

I’ve written a bit more about hackney coaches here , and you can read Dickens’s full version (which originally appeared in Bell’s Life in London in November 1835) here in Sketches by Boz .

1823 Hackney Cab

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

1823 Hackney Cab

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 06, 2016 21:30

January 4, 2016

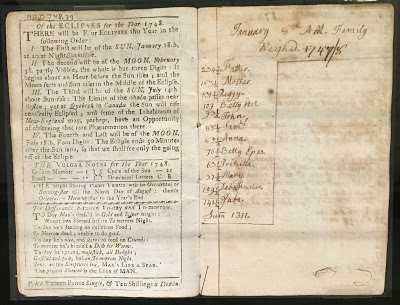

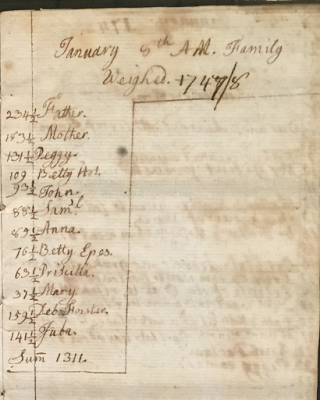

Weighing In for 1748

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Updated January 7, 2016.

The new year is often a time of grim resolutions to undo all the merry-making of the holidays. If the rush of advertisements for weight loss gimmicks and flashy gyms are any indication, there are many Americans who had a sobering confrontation with their bathroom scale on January 1 (or maybe the second.)

But apparently this isn't anything new. In 1748, a young man noted the results of his family's January weigh-in. Born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, John Holyoke (1734-1753) was the son of Edward Holyoke, who became the ninth president of Harvard College in 1737 and moved his family to Cambridge, outside of Boston. Fifteen-year-old John kept an informal diary on the interleaved pages of his copy of An astronomical diary, or, An almanack for the year of our Lord Christ, 1748 by Nathaniel Ames. On these pages, John wrote of the things that interested him: the weather, family illnesses, and his own studies, travels, and daily activities

Opposite a list of the year's eclipses, above, John made his first note for the new year, titled "January 8 AM. Family Weighed 1747/8." (Detail below right; click to enlarge.) In the days before personal scales, weighing oneself meant going to a commercial establishment and using the same scales employed for weighing goods and produce. This wasn't merely a colonial hardship; in faraway London, even dukes presented themselves to be weighed on the commercial scales of Berry Brothers & Rudd . Apparently John's father must have taken his entire extended household to one such set of scales to start the year, and John wrote down the results.

The results are interesting. We modern people tend to think of our counterparts in the past as being much smaller. True, at 93 1/2 lbs, John himself was on the slight side for a young man his age, but his mother weighed 183 1/2 lbs, and his father weighed a substantial 234 1/2 lbs! All those half-pounds must have been important - especially since John totaled everyone's weight for a neat sum of 1316 pounds.

I guessed that Betty Epes, Betty Hol., and Deb Forster are grown cousins, aunts, family friends, or perhaps servants, and it turned out I was right. Thanks to one our "friends of the blog", historian and writer J.L. Bell, I've learned since writing the original post that I was (mostly) guessing right. All were members of the extended Holyoke household; please see his own post here to learn the details of this "blended" family.

But the last name and weight on the list belonged to an individual who most likely lived beneath the same roof, but wasn't considered a true member of the extended Holyoke family. That final entry with a single name belonged to Juba, the family's black slave.

John Holyoke's diary is included in a fascinating exhibition (free and open to the public) currently on display in Harvard University's Pusey Library. Opening New Worlds: The Colonial North American Project features archival and manuscript treasures relating to 17th and 18thc North America, all from the university's libraries and collections. Reflecting every aspect of colonial life, the documents range from diaries and journals to maps, doodles, sermons, and music. The project will digitize the entire collection, and make the documents available for wider study; click here for more information.

Above: Pages from John Holyoke's diary, 1748. Harvard University Archives.

Published on January 04, 2016 21:00