Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 62

February 29, 2016

Answering Nature's Call in Paris in the 1800s

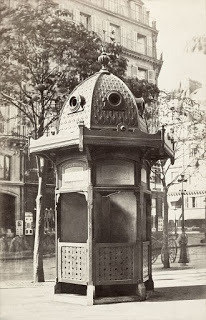

Domed cast iron urinal

Loretta reports:

Domed cast iron urinal

Loretta reports:This article* about public urinals in Paris reminded me—again—of the emphasis on beauty as well as utility that prevailed well into the early part of the 1900s. Even factories made of plain red brick had their artistic flourishes and touches. If you’ve ever been inside an old factory building, you might have noticed the effort to add beauty to elevators, handrails, and so on. Structures built for utilitarian purposes might feature stained glass or elaborate cast iron work.

I suppose the modern styles of urinals are easier to maintain and keep clean, but I find myself wishing a way could be found to make them add something to the aesthetics of the street.

Urinal with eight stalls

Photographs by Charles Marville (1813-1879). Above left:

Cast iron urinal

with domed roof, on curb of street, Place du Théâtre Français, Paris, France, circa 1865, courtesy State Library of Victoria under the Accession Number: H2011.126/33. Below right:

Urinal with eight stalls

surrounded by shrubbery screen, a lamppost with single lantern at each end of stalls, Jardins des Champs-Élysées, Paris, circa 1865, courtesy the State Library of Victoria under the Accession Number: H88.19/2/107a. Both images via Wikipedia. (If you click on the Wikipedia link, you'll find a direct link to the State Library of Victoria image.)

Urinal with eight stalls

Photographs by Charles Marville (1813-1879). Above left:

Cast iron urinal

with domed roof, on curb of street, Place du Théâtre Français, Paris, France, circa 1865, courtesy State Library of Victoria under the Accession Number: H2011.126/33. Below right:

Urinal with eight stalls

surrounded by shrubbery screen, a lamppost with single lantern at each end of stalls, Jardins des Champs-Élysées, Paris, circa 1865, courtesy the State Library of Victoria under the Accession Number: H88.19/2/107a. Both images via Wikipedia. (If you click on the Wikipedia link, you'll find a direct link to the State Library of Victoria image.)*Sent to me by my alert-to-nerdy-history husband.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on February 29, 2016 08:58

February 27, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of February 22, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The enduring appeal behind an iconic Boston painting .

• "Under the influence": mesmerism in England.

• Tickets on the royal dime: a tattered document tells what royal mistress Nell Gwyn saw at the playhouse.

• Skiing through the Depression (and colorfully, too.)

• How the Spirella Corset Company forever changed women's undergarments .

• The latest technology in 1790: George Washington ordered these argand lamps for Mt. Vernon.

• Scottish myths: Wulver the kind-hearted Shetland werewolf .

• Image: 1911 census page where a suffragette refused to complete: "no vote no census."

• How the wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert was celebrated in India.

• Preserving and displaying a pair of Egyptian curtains from 6th-7thc AD.

• While Charles Darwin was writing hist masterpiece, his children were drawing on it.

• Belinda's petition: how an ex-slave successfully won a case for reparations in 1793.

• Sex in the Middle Ages.

• Eighteenth century families on terraces and out-of-doors in art.

• Image: Waiting for parcels of food , Cheapside, London, 1900.

• Harry Stokes and " female-husbands " of the 1800s.

• How Catherine de Medici made gloves laced with poison fashionable.

• "She was both poxt and clapt together": confessions of sexual secrets in venereal cases.

• Ancient Pompeii lives again as Italian officials unveil six more restored ruins.

• What makes Franz Liszt still important?

• Pocket Books and Liquid Bloom: advertising in the 18thc Lady's Magazine.

• Image: What the Victorians threw away: alphabet cup .

• The strange and mysterious history of the ouija board .

• Scientist Mary Somerville will be the first woman other than a royal to appear on a Scottish banknote.

• Mrs. Abigail Norman Prince and her French evening shoes , 1875-1885.

• Crime keeps you young - or maybe not.

• Pancake Day in the Georgian era.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on February 27, 2016 14:00

February 25, 2016

Tudor Era Cleanliness

Frances, Lady Bridges 1587

Loretta reports:

Frances, Lady Bridges 1587

Loretta reports:Looking at the title of this post, some readers will wonder what cleanliness has to do with the Tudor era. It tends to be assumed that our forebears were dirtier and smellier than we are.

As has been pointed out in a number of 2NHG posts,* this may not be the wholly correct picture. It turns out that the lives of our ancestors are not always what we supposed they were. Sometimes our assumptions are mostly true, sometimes there’s an element of truth, and sometimes what we take to be true is, essentially, historical myth.

How To Be a Tudor

Certainly,

this piece by historian Ruth Goodman

, on Tudor-era cleanliness, made me rethink my ideas about the Tudor era. I offer it in place of the Friday Video.

How To Be a Tudor

Certainly,

this piece by historian Ruth Goodman

, on Tudor-era cleanliness, made me rethink my ideas about the Tudor era. I offer it in place of the Friday Video.Ruth Goodman, by the way, has written other books about her experiences living the life of the past. How To Be a Tudor is the most recent. How To Be a Victorian is next in line on my History Books TBR shelf.

*Some samples of our posts about cleanliness are here , here , here , here , and here .

Image: (Unknown artist) Frances, Lady Bridges 1587, courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on February 25, 2016 21:30

February 24, 2016

From the Archives: More About Sultanas, c.1770

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Since I'm visiting Colonial Williamsburg this week, I thought I'd share one of my favorite posts from a past trip.

Recently I shared a pair of portraits of two 18th c. ladies , both wearing pink costumes called sultanas. It's most likely that both ladies were wearing versions of the stylish costume as provided by the artists. But a conversation this week with Sarah Woodyard, mantua-maker's apprentice in the Historic Trades program of Colonial Williamsburg , made me want to share a bit more about this interesting garment.

Yes, the exotically-named sultana was fashionable attire for a portrait, but ladies were also choosing them for elegant at-home wear, too. Cut in a relaxed T-shape much like a gentleman's wrapping gown , sultanas were usually worn without stays, and must have been wonderfully comfortable in comparison to a closely fitted gown over boned, laced undergarments.

Sultanas could be worn loose and open over another gown or shift, right, or wrapped and tied into place with a sash or belt. The simple shape displayed sumptuous fabrics like silk to best advantage, and the sultanas in portraits are often made more luxurious with fur trimming.

Versions of sultanas and wrapping gowns first appeared in England in the late 17th c., and were both inspired by clothing that had made its way through the trade routes to Turkey, India, and China. Such clothing was not only exotic and fanciful, but carried with it the new sophistication of Orientalism, a tangible symbol of England's growth as a world power.

A gentleman might (and did) wear his wrapping gown over breeches and a shirt as informal daywear away from home, but ladies only wore their sultanas at home, or as part of a fancy-dress costume a la Turque, below left. Despite their richness, the unstructured simplicity of a sultana implied intimacy. A lady could receive guests in her drawing room wearing a sultana, and one would also be considered the perfect, slightly daring dress for the hostess of an intellectual salon.

The Colonial Williamsburg mantua-makers had made a replica sultana c. 1770 of pink changeable silk taffeta, above left. Inspired by the two portraits in my post, Sarah dressed one of the shop's summer interns, Monica Geraffo, as a Georgian lady at home in her sultana, her tatting in her hand and her workbag on the table beside her. True Nerdy History Girl inspiration!

Many thanks to Sarah Woodyard and Monica Geraffo for their assistance with this post.

Above left: Photograph © Susan Holloway Scott.

Right: detail, Catherine Fleming, Lady Leicester, by Francis Cotes, c.1775. Tabley House Collection.

Lower left: detail, Mrs. Trecothick, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, c. 1772. Christie's.

Published on February 24, 2016 21:00

February 22, 2016

Death of John Keats

John Keats

Loretta reports:

John Keats

Loretta reports:William Hone , the author of Hone’s Every-Day Book (which I frequently cite) wasn’t shy about giving his opinions, a trait that landed him in court more than once.

I was aware of Byron’s having joked that a bad review finished Keats off. This entry in the Every-Day Book, though, was rather more touching, and very much in Hone’s plain-spoken, pugnacious spirit. Any writer who’s suffered a nasty review can testify to the unpleasantness of the experience. It has certainly aided and abetted writer’s block in some cases; aroused defiance in others. Has it ever hastened an author’s death? I don’t know. But I promise you that it has led to some writers' fantasizing about hastening the critic’s demise.

In fact, though it’s generally agreed that Keats died of consumption (tuberculosis), there is debate about the role mercury played in shortening his life. He has written that he took it, so that’s not disputed. But why is another question. Some believe he took it to treat a venereal infection ; others point out that mercury was used to treat other ailments, and Mr. Keats's health issues were complex.

~~~February 23.Chronology.1821. John Keats, the poet, died. Virulent and unmerited attacks upon his literary ability, by an unprincipled and malignant reviewer, injured his rising reputation, overwhelmed his spirits, and he sunk into consumption. In that state he fled for refuge to the climate of Italy, caught cold on the voyage, and perished in Rome, at the early age of 25. Specimens of his talents are in the former volume of this work. One of his last poems was in prospect of departure from his native shores. It is an

Ode to a Nightingale.My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk; Tis not through envy of thy happy lot, But being too happy in thine happiness,— That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees, In some melodious plot Of beechen green, and shadows numberless, Singest of summer in full-throated ease. ... *

This ode was included with "Lamia, Isabella, the Eve of St. Agnes, and other Poems,” by John Keats, published by Messrs. Taylor and Hessey, who, in an advertisement at the beginning of the book, allude to the critical ferocity which hastened the poet's death. —Hone’s Every-Day Book Vol II (originally published 1827)~~~

*Please click on above the link to the Every-Day Book for the full poem.

Image: Cover of May Clarissa Gillington Byron's A Day with Keats (1913) courtesy Project Gutenberg.

Published on February 22, 2016 21:30

February 21, 2016

Fashionable Technology, c.1740

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,When I first glanced at this 18thc. genre painting, Midday (it's part of a series of four pictures showing the times of the day), I did a double take. Were these ladies looking down at a cell phone? Of course they weren't - the lady in blue is holding a gold pocket watch, below, not an iPhone, whose invention was still some 250 years in the future.

But the inclusion of that pocket watch made me think. Although pocket watches had first come into use in the 16thc., in 1739, when this picture was painted, they remained a luxury item that only the affluent would have possessed. It was a status piece, often beautifully crafted of precious metals and enhanced with jewels, engraving, and enamel, and comparable to expensive designer watches today.

Yet a watch wasn't just a piece of jewelry. A pocket watch represented the newest technology of the time, a tangible representation of the Age of Enlightenment in precise clockwork. The miniaturization of a clock that could be held conveniently in your hand and carried in a pocket was still a marvel. For the first time in history, people were able to measure their days and nights by hours and minutes instead of the movements of the sun and the moon in the sky overhead

Watches marked not only the passage of time, but also introduced the concept of punctuality, which previously had been fluid at best. In an earlier era, the four people in this painting would have known it was noon because the sun was at its zenith, and a nearby church bell might be tolling the hour. Now, in 1739, they had the watch to tell them, its face proudly displayed so that all could read it.

Which, really, is not so very different from a group of young people today, consulting the glowing little screen in their hand that tells them the time, the weather, the nearest, best place for pizza....

Above: Detail, The Four Times of Day: Midday by Nicolas Lancret, c. 1739-41, The National Gallery, UK.

Published on February 21, 2016 17:00

February 20, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of February 15, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Touching love-letters from sailors at sea.

• Wonderful: The friendship book of Anne Wagner, compiled 1795-1834.

• Street life in Victorian London, captured in photographs.

• History of a chair that probably belonged to John Hancock .

• The introduction of anesthesia : imagine surgery without it.

• Curious 18thc cats .

• Image: The 1587 death warrant for Mary, Queen of Scotts , signed by Elizabeth I.

• Parcels and boxes : 19thc textile shopping.

• A 1765 complaint about a wife eloping begins an investigation into an unhappy marriage .

• Not entirely accurate, but still interesting: the Belle Epoque body-con dresses that shocked early 20thc Paris.

• In the 15th-17thc, earwax was considered both versatile and useful.

• Thackeray's own original drawings for Vanity Fair reveal points not mentioned in the text.

• Who invented the first false eyelashes ?

• Image: Marie Antoinette's Green Library from Versailles.

• The problem with "always" and "never" in historical costuming (and really history in general.)

• Courting and romance in the 18thc press.

• Forget the groundhog - according to Anglo-Saxon calendars, February 6 is the last day of winter .

• Five lovely letters on the pleasures of reading and the benefits of libraries .

• Image: Word War One poster warning against spies .

• Was Charles Dickens the first celebrity medical spokesman?

• As "White Mouse", Nancy Wake was among the most decorated secret agents of the World War Two.

• The noisy Middle Ages.

• What do Thomas More, Hans Sloane, and a Moravian burial ground have in common?

• Junk mail is nothing new, as these 19thc examples show.

• Did Martha Washington really have a • Image: Block and axe from the Tower of London that was also used as a child's chair in a Yeoman Warden's quarters!

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on February 20, 2016 14:00

February 18, 2016

Friday Video: Washing a 17thc. Royal Tapestry

Isabella reporting,

Housekeeping in a royal palace is a bit more complicated than a quick run-around with the vacuum. Priceless furnishings and artwork require special treatment that is often complicated, costly, and technologically challenging.

The tapestries that were hung on the walls of Hampton Court Palace not only displayed the wealth and power of the royal family, but also helped keep back the drafts in the vast (and largely unheated) rooms of the Palace. Over the centuries, the tapestries also attracted dust and dirt that had diminished their visual impact and stressed their fibers. But how do you clean a tapestry that's as large as a small house?

This wonderful short video shows how textile conservators tackled the task of washing February, one of the largest Mortlake tapestries in the Palace's collection. The wash bath was specially built for the tapestries, using de-ionised (soft) water, a custom detergent mixture, and the most gentle of touches. For more about conserving the tapestries, see the Palace's website here .

If you received this post through an email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Click here to watch the video.

Published on February 18, 2016 21:00

February 17, 2016

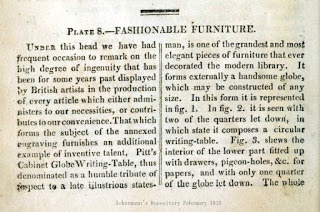

Pitt's Cabinet Globe Writing-Table of 1810

Cabinet Globe Writing-Table

Loretta reports:

Cabinet Globe Writing-Table

Loretta reports:Looking into catalogs of early 19th century furniture, I’m always struck by the number of multi-purpose items. We’ve shown some of these articles in previous posts. ( Here , here , here , and here are some examples.)

For me, Pitt’s Cabinet Globe Writing-Table epitomizes this “high degree of ingenuity ... displayed by British artists,” as well as the “ elegance and usefulness ” so highly prized in the time before Form Follows Function and Less Is More.

Sometimes I wonder whether less is simply less.

Cabinet Globe description

Cabinet Globe description

Description continued

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Description continued

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on February 17, 2016 21:30

February 15, 2016

The Significance of a Diamond-Studded Bicycle, c1890

Isabella reporting,

Diamonds may be a girl's best friend, and those best friends usually appear in a ring. But the unknown lady who wore this brooch was probably revealing a good deal more about herself than that she liked sparkly jewelry.

True, the small (it's less than 3" long) bicycle fashioned of gold with diamond "tires" and a ruby lantern does have plenty of flash. Most likely a custom-designed piece, it's beautifully made: the wheels spin and the pedals turn, and there's even a tiny bicycle chain that turns with the rear wheel. It would have been expensive, a brooch for a lady who probably already had other, more serious diamond pieces in her jewel box.

But a bicycle brooch wouldn't have been merely whimsical in the 1890s. According to the museum's website, this represents a very specific kind of British bicycle designed for a serious cyclist, the rare woman who wore "rational cycling dress" or bloomers for riding. Most 19thc women's bicycles omitted the support bar above the wheels to accommodate long skirts; today many women's bicycles still don't have that bar, even though young girls getting their first flashy pink bikes aren't going to be riding them in trailing petticoats. The woman who wore this brooch would have understood the difference, and would likely have been proud to show how dedicated she was to her sport.

Yet a bicycle brooch in the 1890s would have suggested much more than just sport. Bicycles offered women an exhilarating new freedom, an ability to travel on their own and at will in a way that they'd never experienced before (see this earlier blog post on the subject.) A woman riding a bicycle was a strong, capable woman who didn't need to rely on a man to determine where she going. By extension, this new freedom was closely tied to the suffragist movement. A diamond-studded bicycle brooch would have been seen as making a statement for female independence, and for women's suffrage.

Above: Bicycle brooch, probably English, mid-1890s. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph courtesy of the MFA, Boston.

Published on February 15, 2016 21:00