Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 18

March 6, 2018

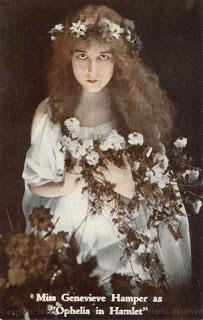

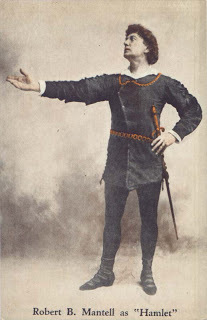

Genevieve Hamper, the Most Beautiful Face on Earth

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:My husband, who recently debuted his own nerdy history blog , has acquired some fascinating material in the way of postcards. Thanks to him, I discovered Genevieve Hamper (1888-1971) and Robert Mantell (1854-1928).

A search brought me to advertisements and reviews of their first motion picture a “surpassing Photo-Play debut of Robert B Mantell America’s foremost Tragedian and Genevieve Hamper Most Beautiful Face on Earth in a stirring arraignment of Society’s Sins The Blindness of Devotion.”

The quote is from a publicity ad in New York Evening Telegram November 1915. It’s here in Rex Ingram, Hollywood’s Rebel of the Silver Screen . There’s more concise coverage on the Turner Classic Movie page for the film .

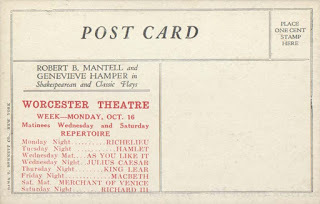

However, as the ad indicates Ms. Hamper and her husband Mr. Mantell were already highly regarded stage actors. Though, apparently, they never made it big on Broadway, they traveled all over North America, putting on a series of plays—not one play, for a week, but, as the post card shows, eight performances of different “Shakespearean and Classic plays.” Obviously, these were greatly abridged.

My impression was, this was rather like the traveling theater troupes Dickens portrayed in Nicholas Nickleby , but quite a bit smaller. From all I’ve been able to discover, there were three players at most in the performances. Not that this means they didn’t put on a good show. As I described in a blog post some years ago, I saw a splendid one-man performance of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol . I suspect the audience at the Worcester Theatre got their money’s worth, too.

To give you an idea of how famous they were, the Theatre Magazine of 1921 devoted two pages to photos of their place in N.J ., where they spent summers rehearsing

Though they continued to make films after The Blindness of Devotion, it seems that these, like so many of the era, did not survive.

Thanks to Larry Abramoff, our dear friend, who donated his amazing collection of post cards to my husband’s project.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

Published on March 06, 2018 21:30

March 4, 2018

How Many Hours to Stitch a Woman's Gown in 1775?

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,For an 18thc mantua-maker (dressmaker), time truly was money. Unlike today, when we put the premium on the labor and skill that goes into creating something by hand, the most valuable part by far of a garment in 1775 was the fabric.

In an era when nearly all new clothing was custom made to order, the fabric was selected, the design was chosen, and a price agreed upon, including the cost of cutting, sewing, and fitting the garment. That last part - the actual creation of the garment - was the smallest part of the overall cost, and it wouldn't change whether the sewing was done by one woman, or three. Labor was charged by the garment, not by the hour. The mantua-maker and her seamstresses had to be able to work fast. Keep in mind, too, that sewing machines had yet to be invented, and every stitch was done by hand.

According to advertisements in English newspapers of the time, the cost for making up a "common gown" or "English gown", a relatively plain dress worn for everyday, was 2-3 shillings. That same sum was also the daily wages for a journey-woman mantua-maker: a woman who had completed her apprenticeship, but was still comparatively new to the trade. In other words, to make a profit, that journey-woman had to make that gown in less than a day.

How long was that workday? For most 18thc tradespeople, the workday was measured by daylight. Therefore a workday in the summer would be much longer than one in the depths of December, averaging to about a twelve to thirteen hour workday. Although work could be done by candlelight or firelight, the cost of those candles or firewood would eat into the already-slender profit. Sunlight, however meager, was free, and every minute treasured.

Could a modern mantua-maker work this fast as well? Janea Whitacre, mistress of the trade in the Margaret Hunter shop, Colonial Williamsburg , recently conducted a time-study of how quickly she could create a 1775 common gown. The gown was made of cotton, a reproduction of a block-printed cotton in Colonial Williamsburg's collection, and complete with the slightly misaligned pattern typical of 18thc printed textiles. About five yards of fabric was used; the fabric's width of 42"-45", still the most common width today, was also the standard English ell in use in 1775.

The petticoat (underskirt) was not included in the trial. Gowns of this style were often worn with a contrasting petticoat - consider this 18thc "mix and match" separates - and it's likely that a woman would already have a petticoat in her wardrobe to wear with the gown. The gown's customer would have been a woman of the middling sort, who would have worn this style for "undress," or informal daily wear.

Janea kept track of her time by a stop-watch instead of the sun, and unlike her 18thc counterparts, she periodically paused in her sewing to interact with CW visitors to the shop. Although speed was Janea's goal, she wanted to please her fictitious customer as well. She took care to incorporate the fabric's stripes with the gown's design with inverted back pleats towards the center, and added contrasting cherry-red bows to the bodice and skirt.

High fashion for her customer, and a profit for her as well. Janea's final start-to-finish time for this gown was ten hours, seven minutes: well within that standard twelve-thirteen hour workday. Best of all, her customer (here represented by apprentice Rebecca Starkins ) looks most pleased with the final result.

Many thanks to Janea Whitacre and Rebecca Starkins for their assistance with this post. For an example of a more elaborate (and therefore more expensive) 18thc dress made by the Margaret Hunter mantua-makers in a day, see my earlier post here .

Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott

Published on March 04, 2018 17:00

March 3, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of February 26, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• A free online course about British royal clothing.

• Ada Blackjack , an Intuit woman without wilderness skill, joined a 1920s Arctic expedition as a seamstress, and outlived four male explorers.

• Presidential valets : confidantes of the wardrobe.

• The illness and death of Queen Mary I .

• Frances Albrier was a 20c activist, politician, labor organizer, and the first African American woman welder in the shipyard industry during WWII.

• A fatal duel in 1834, fought between two U.S. congressmen - with rifles.

• Image: During the WWI, women's football team " Palmers Munitionettes ", made up of munitions workers, were unbeaten.

• Three historic explorers who were captivated by mermaid sightings.

• The 400-year-old history and intrigue of Santa Fe's Palace of the Governors .

• The grisly secrets of dealing with Victorian London's dead.

• Image: Abigail Adams' dimity pocket .

• A tiny locket dictionary , c1900, to wear close to your heart.

• How did Napoleon manage to escape from Elba?

• Women on trial: British soldiers' wives tried by court martial during the American Revolution.

• Proof that cancer isn't a modern disease: discovery of a 3,000 year old skeleton of a young male sufferer.

• Britain's first national lottery , 1816.

• Explore the British Library's Harry Potter: History of Magic exhibition online.

• The enigma of Edinburgh's miniature " fairy coffins ."

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on March 03, 2018 14:00

March 1, 2018

Friday Video: Eighteenth Century Pockets

Susan reporting,

Here's the latest delightful short video in a new series featuring 18th century clothing. This one shows the somewhat mystifying (to 21stc people) pockets worn at the time by women of every class in Europe and America. Tied around the waist beneath petticoats, pockets were the carry-alls for a woman's little necessities of everyday life.

When skirts narrowed and waistlines rose at the end of the 18thc, the new sleeker skirts had no place to hide a pocket, and instead women began to carry small purses and reticules separately - a fashion trend that continues today. However, when I see that modern designers are attempting to revive the 80s fashion for fanny packs, I wonder if tie-on pockets can be far behind. Where fashion is concerned, what's old is always new.

Many thanks to Pauline Loven for sharing this video with us. Pauline is the costume historian, costumer, and heritage film producer who creates the costumes and contributes the historical background for this series, which is directed by Nick Loven for Crow's Eye Productions. For more of their videos, see Dressing an Eighteenth Century Lady , and The Busk .

If you receive this video via email, you may be seeing an empty space or black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on March 01, 2018 21:00

February 28, 2018

Fashions for March 1825

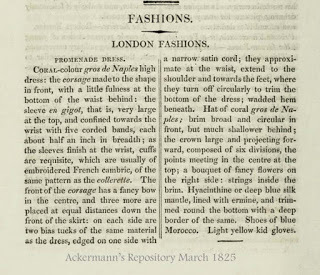

Promenade Dress March 1825

Promenade Dress March 1825

Loretta reports:

If you compare with last month’s fashion post , you’ll see that the waist has dropped and the shape has evolved from the vertical line to what will eventually become in the 1830s two nearly equal triangles at top and bottom. For the 1820s, though, both skirts and puffy sleeves are still moderate.

Regarding the ball dress description: According to Cunnington’s English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century , bouillon is “a puffed-out applied trimming.” Crèpe lisse is an uncrimped silk gauze.

This red and white dress at the Met Museum will give you a better idea of what this sort of trim—and this shape of skirt—looked like in real life.

Promenade Dress Description

Promenade Dress Description

Ball Dress March 1825

Ball Dress March 1825

Ball Dress Description

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Ball Dress Description

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on February 28, 2018 21:30

February 27, 2018

How Young Was America's Founding Generation in 1776?

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,A version of this post originally appeared on my other blog, but it seems so appropriate now that I'm sharing it here, too.

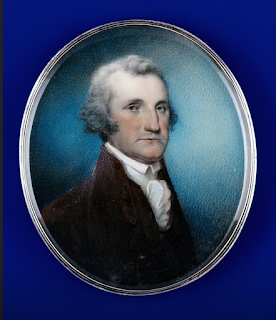

This miniature portrait of Lt. Colonel John Laurens is one of my favorite paintings in the Portrait Gallery in the Second Bank , part of the Independence National Historic Park in Philadelphia . It's easy enough to overlook. Like so many 18thc miniatures painted in watercolors on ivory, this one needs to be protected from light to keep from fading, and unless a visitor pushes aside the dark cloth shrouding its glass case (which you're invited to do; I didn't break any rules!), it will be missed. It's also tiny, the most miniature of miniatures. Including its frame of enamel work and cut garnets, it measures only 1-3/4" high.

But that's not a face meant to be forgotten. John Laurens was born in Charleston, SC in 1754, into a family remarkable for its power and privilege, and wealth created on the backs of enslaved men and women. Tall and handsome, well-spoken and intelligent, Laurens was educated abroad and destined for a career in law. The Revolution changed that, and against his father's wishes, he joined the staff of Commander-in-Chief Gen. George Washington as an aide-de-camp in 1777. He was 23. He became close friends with both the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton, who considered Laurens his dearest friend in the military.

Known for his daring and impetuous courage in battle, Laurens was equally daring in his beliefs. Despite being the son of a slave owner and seller, Laurens believed that all Americans, regardless of race, should be equal in the new republic, and he campaigned for the enlistment of enslaved men in the Continental Army as a way for them to earn their freedom - an unpopular idea that was never put into action.

Laurens made his mark on both the battlefield and as a statesman, serving as a special minister to France with Benjamin Franklin to help secure French aid for America. He fought in the last major battle of the war at Yorktown and survived, only to be killed in a meaningless skirmish in 1782, weeks before British troops finally left America for good. He was only 27, his immense promise cut short.

This miniature was a copy of an earlier portrait by the same artist, and was painted after Laurens' death as a memento for one of his former comrades, Maj. William Jackson. The Latin motto around the miniature's frame reads "Dulce et Decorum est pro patria mori" ("It is a sweet and honorable thing to die for one's country." A noble sentiment, indeed. But Laurens' good friend Alexander Hamilton was devastated, and in one of those historical "what if's" it's impossible not to wonder what both men would have achieved together if Laurens had lived.

All of which made me think, too, of how young so many of the major figures of the American Revolution were when the Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776. My two main characters in I, Eliza Hamilton were among the youngest: Alexander Hamilton was around 21 (his birthdate is uncertain), while his future wife Elizabeth Schuyler was 18. John Laurens was 21, and Aaron Burr 20. The Marquis de Lafayette was 18, Betsy Ross 24, Henry Lee III 20, James Monroe 18, and James Madison 25. For fans of the TV series TURN, John Andre was 26, Benjamin Tallmadge 22, Robert Townsend 22, Abraham Woodhull 26, and Peggy Shippen a mere 16. Slightly older (though not exactly greybeards) were Abigail Adams at 31, Thomas Jefferson 33, John Hancock 39, Thomas Paine 29, and John Adams 40. Even George Washington, the future Commander-in-Chief, was only 44, and his nemesis King George III was 38.

They were young men and young women brimming with enthusiasm, dedication, and fierce devotion to their ideals and dreams, and to making their world a better place. Consider how our current government is one of the oldest in American history: the average age for members of the House of Representative is 57 and for Senators 61, with a president who's 71. I, for one, am glad to see that revolutionary youth and spirit once again rising up today among those who born around the turn of the 21st century. Who knows what brave new things they, too, can accomplish?

Above: Miniature Portrait of John Laurens by Charles Willson Peale, c1784, Independence NHP.

Published on February 27, 2018 12:47

February 25, 2018

A Duke's Household

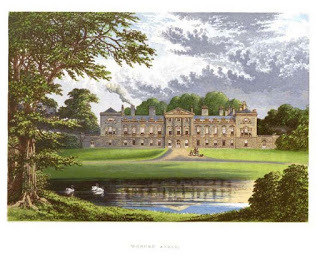

Morris, Woburn Abbey 1866

Loretta reports:

Morris, Woburn Abbey 1866

Loretta reports:In A Duke in Shining Armor , my heroine says, “It’s good to be a duke.”

Though dukes, by and large, are nothing like as numerous or as attractive as we paint them in romance novels (as I describe at RT Book Reviews ), and any number have fallen on hard times in the past and present, things were not so bad for the 11th Duke of Bedford.

Reading Lucy Lethbridge’s Servants: A Downstairs History of Britain from the Nineteenth Century to Modern Times , I came upon this:

“At Woburn Abbey, the eleventh Duke of Bedford maintained until his death in 1940 not only a household of at least sixty indoor servants to attend solely to his wife and himself, but two separate, fully staffed residences in Belgrave Square, including four cars and eight chauffeurs; the Woburn parlourmaids were all Amazonian at over five foot ten, as had always been the Bedfords’ stipulation.”

According to the 13th Duke , (who sounds like a pip, and whose books I intend to read):

“‘Guests never travelled with your suitcase, that was not considered the thing to do. It had to come in another car, so you had a chauffeur and a footman with yourself, and a chauffeur and a footman with the suitcase, with another four to meet you. Eight people involved in moving one person from London to Woburn.’”

11th Duke of Bedford in Coronation Robes

While other noble families changed or economized as the times demanded, the Bedfords continued in the lavish late Victorian/Edwardian style until 1940. “The [11th] Duke always started meals with his own cup of beef consommé and a plate of raw vegetables served to him on a three-tiered dumb-waiter. The Duchess’s secretary-companion had her own quarters that included a cook and a maid.” The duke’s mistress had her own rooms with her own staff—on the premises, I assume?

11th Duke of Bedford in Coronation Robes

While other noble families changed or economized as the times demanded, the Bedfords continued in the lavish late Victorian/Edwardian style until 1940. “The [11th] Duke always started meals with his own cup of beef consommé and a plate of raw vegetables served to him on a three-tiered dumb-waiter. The Duchess’s secretary-companion had her own quarters that included a cook and a maid.” The duke’s mistress had her own rooms with her own staff—on the premises, I assume?Apparently, the 11th Duke of Bedford is also responsible for the grey squirrel invasion of England.

Images: Woburn Abbey , from Francis Orpen Morris, The County Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland 1866; 11th Duke of Beford in Coronation Robes , Photo credit: Middlesex Guildhall Art Collection.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on February 25, 2018 21:30

February 24, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of February 19, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Considering a single, surviving silk shoe , made in London c1760.

• Adventures in 19thc knitting (as told by a 21stc knitter following an 1875 pattern .)

• Remembering when London's pubs were full at 7:00 am.

• The remarkable story of James Hamilton , born at Fort Ticonderoga during the American Revolution, and killed at the Battle of Waterloo.

• The Fisk Jubilee Singers : preserving African American spirituals.

• How Victorian governesses were in danger from their employers.

• Image: In case you thought Georgian gentlemen were all nobility and good manners....

• Amazing story of the revival of Pawnee Eagle corn, thought to be extinct.

• Rare Roman boxing gloves found near Hadrian's Wall.

• Student discipline at Amherst College 200 years ago for offenses that included "an opprobrious inscription upon glass" and drinking cherry rum.

• Robert "Romeo" Coates : a very bad Regency actor.

• One of the oldest trees in Manhattan: the " Hangman's Elm" in Greenwich Village.

• Founding Father firepower : metal intended for statues of George Washington was used to arm the Confederacy.

• Image: Delightful "puzzle purse" Valentine, c1810.

• Cornelia Sorabji , the first woman to practice law in both India and Britain.

• Edward Dando, the celebrated gormandizing oyster-eater.

• The man who lived and died in his wife's Brooklyn tomb .

• Recreating Georgian tent follies from c1760.

• Francis Scott Key : A young man and his portrait.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on February 24, 2018 14:00

February 22, 2018

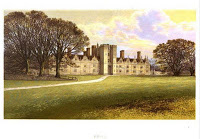

Friday Video: Knole House, Kent

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Rather a long time ago, at the end of the England trip that led to my writing Lord of Scoundrels , my husband and a friend and I visited Knole . By this time, we’d explored a number of stately homes, but Knole was an entirely new experience. This wasn’t simply because the early Jacobean structure was older than many of the homes we’d visited, but because so much of the centuries-old stuff inside wasn't renovated or restored, but the original stuff, fading and tattered. While conservation work is ongoing, and a great deal has been done since we visited, it’s still possible to see some these furnishings, and they do give the place a different atmosphere from that of other great houses. Then, too, there’s the sheer size of the place. I'm pretty sure the impression it made led to my fascination with Jacobean mansions, and having my characters live or get married in them.

Video: Knole - Five centuries of showing off

The video is one from Knole's YouTube channel where, among other things, you can watch conservation in process.

Image: Knole House , from Francis Orpen Morris, A Series of Picturesque Views of Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland: With Descriptive and Historical Letterpress, Volume 6 (1880)

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post or the title of the video.

Published on February 22, 2018 21:30

February 21, 2018

George Washington as Painted for a Scottish Earl, c1792

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Forget President's Day - today is the real birthday of George Washington, born on February 22, 1732 (Georgian calendar.) Two hundred eighty-six years later, he remains the best-known figure in American history: the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, the first president of the United States, and the white-haired gentleman on the one-dollar bill.

As can be imagined, Washington's image was much in demand, and over his lifetime, he sat for many portraits by many artists. The one shown here, however, is different. None of those other portraits were commissioned by a Scottish earl.

David Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan (1742-1829) was a man of many interests. He encouraged engineers designing new kinds of bridges, and he published an essay honoring the controversial Scottish politician Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun. He served both as a diplomat, and as the Grand Master of Scottish Freemasons. His correspondents included Horace Walpole, George Dyer, and George Washington, whom he greatly admired.

When Scottish-born portraitist Archibald Robertson (1765-1835) decided to pursue his career in New York in 1791, Buchan commissioned him to paint a portrait of Washington "that I might place it among those whom I most honor." (You can read the earl's entire letter to Washington here; Buchan also entrusted Robertson with a special gift for Washington, a wooden box said to be made of the oak that sheltered William Wallace.)

In Philadelphia, Robertson painted miniatures of both George and Martha Washington. His portrait of Washington, lower right, shows the president as he likely appeared in late 1791: his hair receding, his cheeks hollowed, and the strain of his responsibilities clear in the general weariness of his expression.

But the portrait he painted at the same time for the Earl of Buchan, above, shows Washington as a younger man. Not only is he portrayed wearing his general's blue and buff uniform from the Revolution, but the years and the cares have been wiped away. His cheeks and hair are fuller, his expression alert and confident: it's the face of the commander-in-chief of the 1770s. Was this done at the request of the earl, or did Robertson decide a little judicious 18thc Photoshopping might make the portrait more agreeable to his patron?

No one now knows. But when Robertson completed the portrait, Washington himself wrote to the earl that:

"The manner of the execution does no discredit, I am told, to the Artist; of whose skill favorable mention had been made to me. I was further induced to entrust the execution to Robinson [sic] from his having informed me that he had drawn others for your Lordship and knew the size which would best suit your collection."

Unfortunately, there's no record of Buchan's reaction to the painting, but one hopes it did find an honored place in the earl's collection. According to ArtUK, over time the portrait suffered damage, was repaired, and perhaps worst of all, became mislabeled as "A Naval Officer." A cataloguer in the 1930s correctly re-identified the portrait as Washington, and in 1951, the current Earl Buchan presented the painting to Sulgrave Manor, the English birthplace of Washington's ancestors, where it hangs today.

Above: George Washington as a Younger Man by Archibald Robertson, c1791-93, Sulgrave Manor.

Below: Miniature portrait of George Washington by Archibald Robertson, 1791-1792, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Published on February 21, 2018 21:00