Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 17

March 18, 2018

An Unfinished Gown with Secrets to Share, c1785

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Historical clothing is collected, preserved, and valued for many reasons. A garment can be considered significant because it belonged to a famous person , or because it belonged to a person whom history has forgotten entirely. Another item could be treasured for the family story behind it, or could have been worn to a significant historical event . A garment can be treasured because it represents the highest level of craftsmanship and skill , or because was fashioned from rare and costly textiles .

And then there is this dress in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg . (Those of you who attended the Costume Society of America 2018 Symposium in CW last week will recognize it from the keynote discussion.) Made in America of printed cotton around 1785-1795 and purchased by CW in 2004, the dress is a popular style of the time known as a common gown. The open-front dress would have been worn over a petticoat (skirt), stays, and a false rump, and would also have had 3/4- or wrist-length sleeves. Depending on the light, the ground-color of the printed cotton appears either dark purple or brown, though chemical analysis has shown it was originally a shade with deep red overtones from a cochineal-based dye.

The reason this gown holds a special place in the CW collection, however, is not what it is, but what it isn't: it was never finished. While sufficiently assembled for fitting, the gown still has extra-wide seams allowances that would eventually be trimmed away and basting threads to hold the pleats in place and to indicate where trim would be added. Most notably, stitching holes indicate that sleeves (now lost) had once been stitched in place, and were then removed. The armholes are quite high, and it's possible that they didn't fit the intended wearer.

Still, no one now knows why the dress was abandoned so close to completion. Yet in this state, the dress reveals a rare glimpse at the mantua-maker's working and construction methods; it's frozen in time, there at the final fitting. In addition, the unworn dress presents a glazed, printed cotton in a pristine condition. For the sake of preserving this glazed finish, it's unlikely that the dress will ever go on public display and risk light-damage to the delicate surface. See more images of the original dress plus descriptions of how the fabric was produced here on the CW e-museum website.

The dress is also unusual for another reason. Most surviving 18thc dresses tend to be small - not because all 18thc women were petite, but because in an era when remodeling and recutting clothing was common, the smaller gowns didn't offer enough fabric to make recycling feasible. This gown was intended for a tall woman - 5'10" or even taller - with a 46" bust and a 42" waist.

While the original gown is primarily a study garment in the collection, it has already inspired several copies. First, the printed cotton fabric has been commercially reproduced for sale (it can be ordered by the yard here .) An exact one-to-one copy of the dress to be used for study was created by CW's Costume Design Center, who also made another copy to be worn as a costume in the historic area.

Finally (at least for now) the mantua-makers of the Margaret Hunter shop in CW's historic trades program made a technological reproduction, recreating the dress using 18thc hand-sewing and other period-correct techniques. This version was completed based on other similar dresses from the period, and is shown right worn by Janea Whitacre, mistress of the mantua-making trade. It's stunning in person - which makes you wonder all over again why the original was never finished.

Left: Gown, maker unknown, 1785-1795, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Photograph courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg.

Right: Technological reproduction gown, made the Margaret Hunter shop, Colonial Williamsburg, 2018. Photograph ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on March 18, 2018 19:43

March 17, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of March 12, 2018.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Read the comic history of England - handwritten and illustrated - that Jane Austen wrote when she was only sixteen.

• Consumptive chic: how tuberculosis symptoms became ideals of beauty in the 19thc.

• A recipe that's perfect for an 18thc spring dinner: pistachio creams .

• James Allen , a Regency-era female husband.

• Image: A canine rail cart trip in Alaska, 1912.

• Pineapples in 18thc America.

• Nineteenth century Quaker Rebecca Lukens , America's first female CEO of an industrial company.

• A caracal for King George II.

• A thaw in the streets of London, 1865.

• Image: An elegant c1775 combined music stand and writing table with Severes porcelain plaque.

• The many residents of this elegant 1872 New York rowhouse included the tragic American-born Princess Rospigliosi.

• The woman with the violin: the trailblazzing Ginger Smock and the 1940s-1950s Los Angeles jazz scene.

• The Victorian ostrich feather trade: boom and bust.

• Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman doctor in America; where she lived and worked in Greenwich Village, NY.

• The importance of coffee, tea, and chocolate in early America.

• Image: First World War police whistle associated with the service of Miss D.A. Lovell in the

• Of sealing wax and Emperor Francis I of Austri a.

• Italian (sort of) restaurants in New York City in 1916.

• Dreams of the Forbidden City: when Chinatown nightclubs beckoned Hollywood.

• Crispus Attucks : American Revolutionary hero?

• Image: Helluva good icicle at 15thc Rosslyn Chapel, Midlothian, Scotland.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on March 17, 2018 14:00

March 15, 2018

Friday Video: Dressing an 18thc Gentleman for "Reigning Men" at LACMA

Susan reporting,

This week I've been attending the Costume Society of America 's annual symposium in Colonial Williamsburg . One of the more fascinating presentations was given by Senior Curator Sharon Takeda and Assistant Curator Clarissa M. Esguerra from the Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), who described the process of creating the 2016 major exhibition Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear 1715-2015. Featuring pieces drawn largely from the museum's own collections, the exhibition challenged the assumption that fashion is only for women, and instead - as the program described it - "celebrated the rich history of restraint and resplendence in menswear, traced cultural influences over the centuries, and illuminated connections between history and high fashion." (The exhibition also received CSA's Richard Martin Exhibition Award.)

This short video offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the show's preparation. Dressing and moving mannequins in rare and delicate 200-year-old clothing is clearly not an easy task - but the beauty and craftsmanship of the menswear glimpsed here makes the video well worth watching. For more information and other images, see the LACMA blog dedicated to the exhibition.

Attention to our lucky readers in Australia: the Reigning Men exhibition has traveled from Los Angeles to Saint Louis in 2017, and will soon complete be on display at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney from May 2-October 14, 2018.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Please click here to watch the video.

Published on March 15, 2018 21:00

Friday Video: "Reigning Men" at LACMA

Susan reporting,

This week I've been attending the Costume Society of America 's annual symposium in Colonial Williamsburg . One of the more fascinating presentations was given by Senior Curator Sharon Takeda and Assistant Curator Clarissa M. Esguerra from the Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), who described the process of creating the 2016 major exhibition Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear 1715-2015. Featuring pieces drawn largely from the museum's own collections, the exhibition challenged the assumption that fashion is only for women, and instead - as the program described it - "celebrated the rich history of restraint and resplendence in menswear, traced cultural influences over the centuries, and illuminated connections between history and high fashion." (The exhibition also received CSA's Richard Martin Exhibition Award.)

This short video offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the show's preparation. Dressing and moving mannequins in rare and delicate 200-year-old clothing is clearly not an easy task - but the beauty and craftsmanship of the menswear glimpsed here makes the video well worth watching. For more information and other images, see the LACMA blog dedicated to the exhibition.

Attention to our lucky readers in Australia: the Reigning Men exhibition has traveled from Los Angeles to Saint Louis in 2017, and will soon complete be on display at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney from May 2-October 14, 2018.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Please click here to watch the video.

Published on March 15, 2018 21:00

March 14, 2018

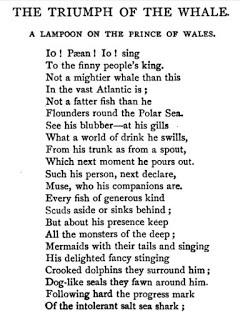

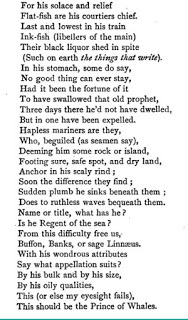

Regency Satire: The Triumph of the Whale

Cruikshank, The Prince of Whales 1812

Loretta reports:

Cruikshank, The Prince of Whales 1812

Loretta reports:On this date in 1812 the Examiner published Charles Lamb ’s poem “The Triumph of the Whale,” which inspired this George Cruikshank satirical print of 1 May 1812 . The image appeared in Cruikshank's satirical magazine, The Scourge.

The caricature and poem about the then Prince Regent (later King George IV) remind us all that mocking the great and powerful, in picture and print (and these days, in internet memes), is nothing new. Given the libel and sedition laws of the time, it’s amazing what Regency satirists got away with. And let’s not forget one of the Privileges of Peers I reported on a while back:

“3. To secure the honour of, and prevent the spreading of any scandal upon peers, or any great officer of the realm, by reports, there is an express law, called scandalum magnatum, by which any man convicted of making a scandalous report against a peer of the realm (though true) is condemned to an arbitrary fine, and to remain in custody till the same be paid.”

Scandalum magnatum notwithstanding, the faces in this caricature would have been familiar to the audience of the time, and everybody would understand the political implications. We, however, need a translation, which the Brighton Museums website provides succinctly:

“Portrayed as a whale in a ‘Sea of Politics’ George spouts the ‘Liquor of Oblivion’ on playwright and Whig supporter Richard Sheridan, and blows the ‘Dew of favour’ on Spencer Perceval the Tory Prime Minister. The prince ignores his former lover, Mrs Fitzherbert, and looks lovingly at his mistress Lady Hertford, who is shown next to her cuckold husband.”The figures on the right—the Tories—viewed as the fat cats of the time, expect to profit further by the Regent’s decision to shun his Whig associates. The Marquess of Hertford is wearing cuckold horns. You can read a much more detailed description at the British Museum website (please click on "More" for the full description and check out the curator's comments as well). Clearly, this is pretty strong stuff, though not as strong, I think, as Lamb’s poem.

The 1812 blog offers a concise summary of Charles Lamb’s life and the poem . Most of the references are clear enough, although I haven't yet figured out why the muse Lamb summons is Io, one of Zeus’s many loves, who was transformed into a white heifer.

These pages are from The Poetical Works of Bowles, Lamb, and Hartley Coleridge Selected 1887

Image: George Cruikshank, The Prince of Whales , from the Scourge of 1 May 1812.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on March 14, 2018 21:30

March 12, 2018

High Style in Rural New Hampshire, c1835

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,This week I'm visiting Colonial Williamsburg to attend the Costume Society of America 's annual meeting. If any of you are attending as well, I hope you'll say hi.

I saw this portrait yesterday in CW's DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum , and felt she definitely deserved a post. Loretta has written many posts (and books!) that feature the exaggerated fashions of the 1830s - an era of big hair, bigger skirts, and the biggest sleeves. You can see examples here , here , and here , all from trend-setting English magazines of the time.

But American women have always possessed a stylish flair and a gift for making European fashions their own. Fashion magazines and trends traveled across the Atlantic as swiftly as clipper ships could bring them. The young woman in this portrait isn't from Paris or London, but from Milton Mills, New Hampshire, a village on the Salmon River bordering Maine.

Martha Spinney Simes (1808-c1883) was in her early twenties when this portrait was painted. She's shown sitting on an elegant (if a bit strangely proportioned) red sofa - the matching portrait of her husband has him sitting on a similar sofa or chair, facing her - that serves to enhance the emerald green of her dress. Her hair is pinned into the most fashionable of glossy knots and twists, with a short braid over one side of her forehead ending in a corkscrew curl.

And her jewelry! Martha has clearly embraced the idea of "more is more." In addition to two cuff bracelets and multiple rings, she wears an elaborate double-strand of glossy black beads, perhaps jet, and what is likely a cameo brooch. Her drop earrings are the real stars, however, over-sized gold drops with pale blue stones (opals, chalcedony, or agate?) that frame her face and help to balance her hair.

What I like best about this portrait is how all this finery doesn't overshadow Martha. Unlike the fashion plates and many European portraits of the time, she doesn't simper or glance sideways. Instead her expression seems forthright, direct, and intelligent, with just a hint of a smile. She's fabulous, and she knows it. And who's going to argue?

Portrait of Martha Spinney Simes (Mrs. Bray Underwood Simes), artist unknown, c1835, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Published on March 12, 2018 21:00

March 11, 2018

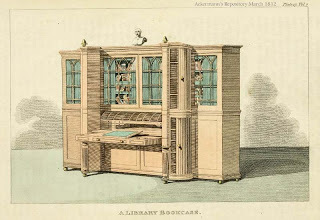

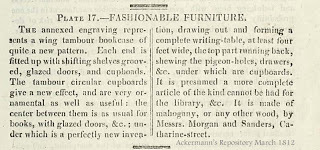

Elegant Bookcase for a Fashionable Regency Library

Library Bookcase March 1812

Loretta reports:

Library Bookcase March 1812

Loretta reports:I set quite a few scenes in libraries, mainly because, by the time of my stories, they had become a family gathering place. Furthermore, in many great houses, these were large, comfortable rooms, often fitted out less formally than say, the drawing room. The one I used in A Duke in Shining Armor is a good example.

While bookcases, complete with writing desk, might appear in various rooms, this one seems to need quite a large room. And even if the library already has miles of bookshelves, those of us who love books can always use storage space for more.

I was particularly struck by the tambour circular cupboards, because (a) while horizontal tambour is fairly common, the circular vertical style is much less so, and (b) one of my own favorite pieces of furniture is a mid-20th century dressing table that has this feature.

Bookcase description

Bookcase description

Images from Ackermann's Repository for March 1812, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, via Internet Archive.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on March 11, 2018 21:30

March 10, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of March 5, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• An 1870s Turkish-inspired fancy dress costume from the House of Worth highlights the transition into women wearing trouser.

• "I desire you would Remember the ladies": read Abigail Adams's most famous and treasured letter to her husband John, written in 1776.

• The strange saga of George Washington's bedpan .

• Quick book quiz : can you spot the titles borrowed from other books?

• Online resources for palaeography - the art of reading old handwriting.

• How new research helped tell the story of Chance Bradstreet , an enslaved man living in 18thc Massachusetts.

• Image: The gilded weathervane of St Mary's church, Kingsclere, is in the shape of a bed-bug.

• How 18thc British women deployed the teapot in the campaign against slavery.

• Abraham Lincoln visits New York's Greenwich Village.

• Despite overwhelming odds, American Edmonia Lewis found international success as a sculptor in 19thc Rome.

• What the history of food stamps reveals.

• Online exhibition traces 150 years of Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland .

• Image: Black women in Early Modern cameos .

• Strikingly detailed images of historic cathedrals each took up to a year to create.

• The story of Brooklyn's fabulous, forgotten Fulton Ferry terminal .

• The 18thc fashion for false rumps .

• Ida Wilson Lewis , lighthouse keeper and fearless Federal worker, who saved 25 lives.

• Creating the next generation of readers : "Children fall in love with reading as a result of falling in love with being read to."

• Video: Beautiful: a rare snowfall covers Rome's ancient monuments.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on March 10, 2018 14:00

March 8, 2018

The Geffrye Museum of the Home

Ornamental glass lustres c. 1880

Ornamental glass lustres c. 1880

Caughley Tea Service c. 1780Loretta reports:

Caughley Tea Service c. 1780Loretta reports:Instead of the usual Friday video, I’m offering a tour of the Geffrye Museum of the Home , which my husband and I visited during our time in London. The draw for me was the series of period rooms .

As Susan and I have often lamented, it’s much easier to find paintings and prints of exteriors than interiors. The Geffrye offers a chance to view some interiors and, especially, to notice the way home life changed over time. These aren’t the homes of aristocrats, but, with the exception of the almshouses, of well-off families of the professional classes.

With the museum closed for development until 2020, I invite you to check out the panoramas and the virtual tour offered on the website—which I supplement with these photographs from our visit.

Photographs by Walter M. Henritze

Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

Published on March 08, 2018 21:30

March 7, 2018

Dining with the Hamiltons (and the Bonapartes), 1804

Susan reporting,

One of the reasons I especially enjoy research with handwritten letters is being able to see the little things that reproduced transcriptions often omit. The excerpt, above, is from the bottom corner of a letter than Alexander Hamilton wrote to Victor Marie du Pont de Nemours in May, 1804. Most of the letter concerns the repayment of a debt, with a complicated explanation of the principal and the interest accrued. As dry as this may be, the letter has importance because of the two parties corresponding - the former Secretary of the U.S. Treasury writing to a prominent French-American diplomat and businessman.

But it's the non-business part of the letter that intrigued me. Aside from the fact that I wish I could end letters with Hamilton's grandiloquent yet breezy closing sentence ("The multiplicity of my affairs will excuse my delay in completing this business"), it's that little postscript to the left that caught my eye.

P.S. I sent you some days since a note requesting you to meet Mr. Bonaparte at my house on Sunday three oClock to dine. I hope to have the pleasure of seeing you.

Yes, Hamilton is displaying his typical impatience because Du Pont hadn't responded to his first invitation, but he's also describing what must have been quite a grand dinner. Mr. Bonaparte was Jérôme Bonaparte, the youngest brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of France (and soon to become Emperor.) While visiting America, the nineteen-year-old Jérôme had fallen in love with Elizabeth "Betsey" Patterson of Baltimore and had married her. An American merchant's daughter did not fit into Napoleon's dynastic plans, however, and the First Consul had already made his displeasure known.

But in May of 1804, Jérôme and Betsey were glamorous newlyweds, and having them as guests must have been a social coup. In addition to the French-born Du Pont, the guest list included Hamilton's good friend, statesman and bon vivant Gouverneur Morris, who had served as the American Minister Plenipotentiary to France. Considering that Hamilton also spoke French fluently, it's easy to imagine French - the language of 18thc diplomacy and worldly sophistication - as the language of choice during the meal.

Several days after this letter, Hamilton wrote a quick note to his wife, Eliza Schuyler Hamilton, to let her know that "On Sunday Bonaparte & wife...with dine with you. We shall be 16 in number...." Because this note is undated, it's impossible to tell exactly how much warning Hamilton gave Eliza before the dinner. At this time, he had his law office in what is now lower Manhattan, and often remained there overnight instead of making the long trek (which could take a couple of hours, depending on the weather) by horse or carriage to the family's country house, The Grange, in the then-rural northern part of Manhattan. Eliza and the couple's younger children were living at The Grange, which would have been site of the dinner.

In the same note, Hamilton asks Eliza to send the "coachee" to town on Saturday - perhaps he intended to provide transportation for at least some of his guests - and the "waggon", probably for more provisions for the meal. He also says that it was "my intention to get out Gentis and perhaps Contoix"; Gentis had been employed by the Hamiltons as a cook, and Contoix had also worked for the family. Clearly Hamilton was planning an impressive dinner.

Now Eliza was an accomplished hostess, and I'm betting that none of this fazed her. She would have handled French guests, extra servants, and an elegant meal with gracious aplomb. While sixteen guests could have been a tight fit in The Grange's dining room, right, the accommodating design of the house would have let her open the doors into the parlor and add another leaf or two to the table. I can also imagine Hamilton himself fussing over every detail of his dinner from the menu to the wines, and sparing no expense, either. With the tall windows open to catch the breezes from the river, it must have been a merry and pleasurable evening indeed.

But the hindsight of history casts an undeniable shadow over this luxurious little dinner.

A little over a year later, the marriage of Betsey and Jérôme Bonaparte would be annulled by Napoleon. Betsey would eventually return alone to America with their infant son, while Jérôme would marry the German princess his brother had chosen. At the time of this dinner, Hamilton had already begun exchanging barbs with another New York lawyer, a conflict that would fester and escalate throughout the spring and early summer. This dinner took place on May 13, 1804. Almost exactly two months later, on July 12, Alexander Hamilton would die of wounds suffered in his duel with Aaron Burr.

Thanks to Lucas R. Clawson, reference archivist & Hagley historian, Hagley Museum & Library, for sharing this letter with me.

Above: Detail of a letter from Alexander Hamilton to Victor Marie du Pont de Nemours, May 1804; collection of Winterthur Museum.

Lower right: Dining room at The Grange, New York, NY. Photo ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on March 07, 2018 21:00