Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 15

April 26, 2018

Friday Video: The Fife Tiara, A Wedding Gift for a Royal Princess in 1889

Susan reporting,

With the next British royal wedding fast approaching, the speculation grows daily as to what exactly American Meghan Markle will wear to walk down the aisle with Prince Henry of Wales. Yes, the wedding dress is the greatest mystery - but right after that comes the question of the bride's headdress. Will Meghan go for something simple like a wreathe of flowers, or will she go the full princess-to-be route with a glittering tiara?

The breathtaking tiara featured here already comes with a royal heritage. Created in the 1880s by jeweler Oscar Massin, the Fife Tiara contains approximately 200 carats of diamonds set in gold and silver. It was a wedding gift to Queen Victoria's granddaughter Princess Louise of Wales, below, daughter of Edward VII, from her new husband, the Duke of Fife; that dukedom was a wedding gift to the groom.

Today the tiara is valued at 1.4 million pounds. Accepted by the government in lieu of taxes, it was permanently allocated to Historic Royal Palaces for display at Kensington Palace. It can be seen there now as part of the Victoria Revealed exhibition.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing a blank space or black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on April 26, 2018 21:00

April 25, 2018

What Ordinary People Wore in the Early 1800s

1808 Woman Churning Butter

1808 Woman Churning Butter

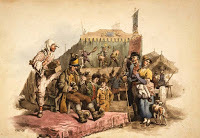

Country Fair 1808Loretta reports:

Country Fair 1808Loretta reports:Given comments on my last blog, it seemed like a good time to look at resources for what working people wore. Susan and I have written about tradespeople and servants here , here , here , here , here , and elsewhere.

They are rarely the subjects of portraits, although they might be included in scenes of, say, a great estate. Also, a few employers actually had at least some of their servants’ portraits painted. Later in the 1800s, Victorian servants appear in quite a few photographs. But for those of us who are looking at English dress before photography, there are other ways to get an understanding of what ordinary people wore.

William Henry Pyne is one of my go-to illustrators. I have two reprints of his work dealing with this subject: Picturesque Views of Rural Occupations in Early Nineteenth-Century England and Pyne's British Costumes .

Online, there’s also his Etchings of rustic figures, for the embellishment of landscape .

Rustic figures

Rustic figures

Rustic figures

Rustic figures

Other sources include satirical prints. Though we need to be aware of exaggerations, they generally seem to get the clothing details right. Images in Ackermann’s Microcosm of London show ordinary people as well as those of the upper orders.

Other sources include satirical prints. Though we need to be aware of exaggerations, they generally seem to get the clothing details right. Images in Ackermann’s Microcosm of London show ordinary people as well as those of the upper orders. In some cases, we see a distinctive uniform for a trade or profession. The watermen or firemen, for instance. Others might wear a certain type of vest. Many professions and trades required badges. Whether one’s clothes were in fashion or not would depend on one’s business. A dressmaker, for instance, would need to look up-to-date. For haymakers , it was another case entirely.

Images:

14. A woman churning butter with a cloth apron tied about her waist and a mob-cap on her head, another woman milking a cow beyond. Title page lettered "The Costume of Great Britain. Designed, Engraved , and Written by W. H. Pyne." "London: Published by William Miller, Albermarle-Street. 1808." Courtesy the British Museum

Couple at fair looking at a clown and a bell ringer , W.H. Pyne, [1808], courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Rustic figures from Pyne, Etchings of rustic figures, for the embellishment of landscape .

Rowlandson, Thames Watermen from Miseries of London 1807I courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on April 25, 2018 21:30

April 23, 2018

Extravagant Hats on French Ladies, 1788

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,As much as I enjoy the immense variety of historical images that now can be discovered thanks to the internet, staring at a jpg on my laptop screen will never replace being able to see the real thing.

Sometimes, that experience is a revelation. One of the paintings featured in the new Visitors to Versailles: 1682-1789 exhibition (currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) is this one: Promenade of the Ambassadors of Tipu Sultan in the Park of Saint-Cloud. The entire painting is shown below (and as always, please click on the images to enlarge them.)

It's a justly famous painting, for it shows how truly international the 18thc world could be: the delegation of Tipu Sultan had come halfway around the world to seek French assistance in removing the British from Mysore, and to negotiate more favorable direct trading with France. Crowds of French people have come to welcome (and likely to gawk at) the ambassadors as they walk in the Park at Saint-Cloud.

When this painting is used to illustrate the international politics of the late 18thc, it's usually a small reproduction that emphasizes the crowds, the lawns, and the nodding greenery. But when I saw it in person, all I could see was the HATS.

The late 1780s were a time of oversized and extravagant hats and caps, with curving brims, plumes, buckles, ribbons, silk flowers, and silk gauze ruffles. The variety of fashionable examples - like wedding cakes for the head! - captured in this painting are truly stunning. It's all in miniature, too; the entire painting measures about 38" wide, so most of these figures are at most a couple of inches tall.

There are also some delightful small dramatic scenes: the little boy either having a tantrum or a fainting fit while his nursemaid scowls up at his negligent mother, upper left; footmen in elaborate royal livery try to contain the crowds around the ambassadors, upper right; and two women have decided it's all too much and have retreated beneath their wide parasol to a park bench, where a black-clad gentleman in a wonderful wig (perhaps a clergyman?) has joined them, lower left.

But my favorite detail, lower right, shows a man selling prints and sheet music. He's wearing jaunty striped trousers and a long-tailed coat as he stands before his wares, which are pinned on rows of strings to display. He's playing a horn for his dog, who is dancing on its hind-legs with a stick in its front paws - what better way to attract customers?

Promenade of the Ambassadors of Tipu Sultan in the Park of Saint-Cloud by Charles-Eloi Asselin, 1788, Cité de la Céramique-Sèvres et Limoges.

Published on April 23, 2018 21:00

April 22, 2018

Fashions for Mature Women in the 1800s

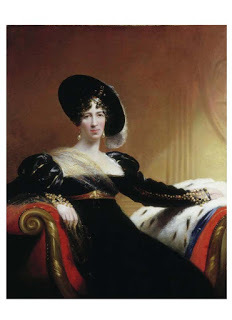

Lady Anne Hamilton at age 49

Loretta reports:

Lady Anne Hamilton at age 49

Loretta reports:A reader asked, “Do you have any fashion plates of older women?”

The answer is no. Whether it’s the 1800s or the 1900s or the 2000s, fashion is most usually displayed on younger women.

The fashions I post monthly seem to be mainly for married women. In France, for instance, unmarried young women were expected to dress with almost nunlike simplicity; and it’s my sense that young English women, while not dressing as severely as their French counterparts, generally did dress more demurely than matrons, at least through the Regency.

Still, there’s nothing matronly about the fashion prints. The images are always of young, slender women with, depending on the era, ridiculously tiny waists. I’ve yet to see older faces or plumper bodies. The fashion plates always show the idealized youthful image of the time.

Then as now, that is the way fashion is sold. A style blog focused on the over-forty woman offers an explanation that I believe is applicable to previous centuries of fashion merchandising.

Today, we do see the occasional exception. A few brands will feature 40+ models and/or fuller-figured women in their advertising. But these are rare. Rarer still are mature and/or fuller-figured models on the runways. This always seems to be the case, even though older women are buying the clothing.

To get an idea of what older women wore in earlier eras, we need to turn to portraits. It's possible that the subject isn’t necessarily wearing the latest fashion. Then as now, a woman might have stuck with a style she found comfortable and believed becoming. However, when it comes to royals and aristocrats, the portraits are generally very stylish, which makes sense: Since they could afford to buy new things all the time, and they weren't shy about showing off their wealth, they were more likely to wear the current fashion when they had their portrait painted.

Maria Amalia of Naples & Sicily about age 57

Maria Amalia of Naples & Sicily about age 57

Let’s also not forget that well-off people were not buying their clothing ready-made. The fashion plate would be no more than a possible starting point. A lady would have her favorite dressmaker, who would adapt styles or create a distinctive look. Though the fashion plates featured young women, I suspect older women then would have had a better chance than we do of getting clothes that fit and flattered them. Dressmakers were far from rare, labor was cheap, and the competition for customers was fierce: It was simply good business to make the customer look great, no matter what her age or figure.

Images:

James Lonsdale, 1815 Portrait of Lady Anne Hamilton (1766–1846), lady-in-waiting to Queen Caroline1815

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Louis-Édouard Rioult after Louis Hersent, Portrait of Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily (1782-1866) about 1839

Current location Palace of Versailles

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on April 22, 2018 21:30

April 21, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of April 16, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The decades-long quest to find and honor the grave of pioneering 19thc black sculptor Edmonia Lewis .

• Treasure maps, pirate utopias, and author Robert Louis Stevenson .

• Little-known story of the six Chinese men who survived the sinking of the Titanic, only to be immediately deported after arriving in NYC.

• The Hancocks of 18thc Boston in wool, silk, and linen.

• GIFs that return ancient ruins to their former glory.

• The Progress of a Water-Coloured Drawing: highlights from a how-to-paint book from 1804.

• Love letters between 19th inmates at Eastern State Penitentiary reveal secret communications and relationships at the famously isolating prison.

• Image: Necklace fashioned posthumously from radical author Mary Wollstonecroft's hair.

• Medieval graffiti : the lost voices of England's churches in the middle ages.

• Women's riding apparel , in the 1920s and now.

• The tragic story of Elizabeth Whitman , the inspiration for The Mysterious Coquette.

• Biscuits, broth, and hasty pudding: the diets of the Romantic Poets.

• Image: All about the honey: a medieval Winnie the Pooh appears in this 15thc Italian manuscript.

• The myth of Dolley Madison and the White House Easter Egg Roll.

• James Ince & Sons, umbrella makers .

• Queen Mary I of England washes the feet of the poor.

• Albany's Willy Wonka: remembering hand-made chocolates .

• Image: Title page of translation of Plutarch's Lives, as critically annotated by Mark Twain.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on April 21, 2018 14:00

April 19, 2018

Friday Video: Loretta's Musket Training

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:I’d never fired a weapon in my life. The closest I’d come was holding Baron de Berenger’s unloaded rifle at the Kensington Central Library.

Last November, I found out from author Caroline Linden that one could fire a black powder weapon at Colonial Williamsburg. Susan Holloway Scott —aka the other Nerdy History Girl—sent me photos of her family's experience not long thereafter. I was sold. There's lots of history one can only read in books. I am not going to turn down a chance to experience it firsthand.

The video is very short. What I learned is very long. I fired two weapons, a musket and a fowler. What you don’t see in the video is Loretta trying to heft either of them. The musket weighs ten pounds, the fowler is a little bit lighter, and they're both looong. My arms shook, lifting the gun. Then I had to hold it and aim at the same time. Also, you don’t see how hard it is to draw back the cock. I had to use two hands. (I really need to work on my upper body strength.) Meanwhile, there's the loading process, with which I received a great deal of assistance. Otherwise, I could have been there for half an hour for each shot. Soldiers could load their weapons in 15 seconds.

These are far from accurate weapons. Even when you know how to aim, you can’t be sure the ball will go where it should. But yes, I did badly wound a couple of paper bottles.

Video: Loretta Shoots!!

On my YouTube Channel

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post or the video title.

Published on April 19, 2018 21:30

April 18, 2018

A 1770s Dress Worn by One of the "Visitors to Versailles"

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Last week I previewed a major new exhibition called Visitors at Versailles, 1682-1789, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York through July 29, 2018. Created in partnership with the Château de Versailles along with loans from many other institutions, the exhibition brings together nearly two hundred paintings, drawings, tapestries, porcelains sculptures, furnishings, books, and costumes (and even a sedan chair) to recreate the era when the palace of Versailles and its gardens truly were the center not only of the France, but also the world of fashion, diplomacy, and sophistication.

Versailles was a public court, drawing visitors from around the world. Yet it wasn't just courtiers jockeying for a moment of king's favor. During the reigns of Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI, Versailles brought together the leading artists, musicians, intellectuals, and master artisans in one place as well, and visitors as diverse as Benjamin Franklin and the seven-year-old crown prince of Cochinchina (modern Vietnam). We can't go back in time to visit Versailles in its 17thc-18thc glory ourselves, but this exhibition is an excellent introduction, and highly recommended.

One of the first galleries features the lavish clothing required by the French court, and I'll be featuring some of these costumes in future blogs. The style of this beautiful silk dress was called a sack, or, more glamorously, a robe à la française. According to the museum's gallery notes:

"Characterized by free-flowing back pleats that extended from shoulder to hem, the robe à la française had been largely abandoned by the 1770s - except at court. A woman conveyed her status not only through the display of rich textiles, but also through her elegant negotiation of the cumbersome hoop under the large skirt, a learned skill intended to give the impression of natural grace."

While the dress and its matching petticoat have survived together, the original stomacher (the triangular insert that filled in the two sides of the bodice) has not. This isn't that unusual. A stomacher was an important 18thc accessory. Because stomachers were pinned into place for wearing, women could easily update an older gown or change its look by swapping stomachers.

According to the Met's website, this dress has been displayed several times before, and it has been shown each time with a different stomacher - perhaps in the spirit of that 18thc lady. For the current exhibition, the dress's fabric and trim were carefully recreated through laser-printing for a matching stomacher inspired by contemporary fashion prints. Earlier exhibitions have featured a stomacher with buttons and lace, and another sported rows of exuberant bows. It's also interesting to see the changing styles in modern display mannequins. Which do you prefer?

Link for more information about Visitors at Versailles, 1682-1789.

Above: Dress (robe à la française), French, c1770-75. Silk faille with cannelé stripes, brocaded in polychrome floral motif, trimmed with self fabric and silk fly fringe. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Top left image by Susan Holloway Scott; all others Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Published on April 18, 2018 19:00

April 16, 2018

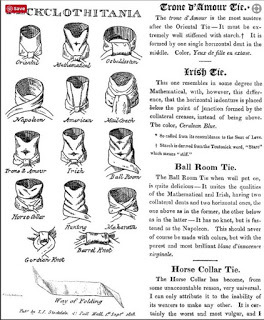

The Neckcloth Part 2

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Last time, in tackling the immense subject of men’s neckwear , I focused on the material in the early 19th century neckcloth, and several readers were kind enough to explain further. The subject is daunting, and I’m taking Mark Hutter ’s remark as my mantra: There is no “typical.”

For instance, stocks were old-fashioned, then they weren’t; “correct” colors and materials changed for both neckcloths and stocks, depending on the occasion and that capricious being, Fashion; and then, some people use the terms interchangeably.

What seems clear is that neckwear offered a way to express one’s individuality, especially after men’s clothing became more subdued in color and more uniform in style, thanks in great part to Beau Brummell.

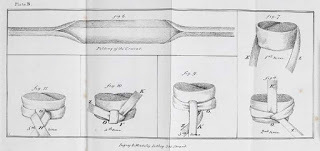

Folding & tying the cravat

One important way of expressing oneself was in the way one tied that important length of fabric.

Folding & tying the cravat

One important way of expressing oneself was in the way one tied that important length of fabric.My neckcloth, of course, forms my principal care,

For by that we criterions of elegance swear,

And costs me each morning some hours of flurry,

To make it appear to be tied in a hurry.*

Cravats for travel

I don’t know the author of this verse. It appears here, there, and everywhere, referring to Beau Brummell. He didn’t write it, but everybody stole it without attribution, as often happened/happens. Still, a great deal was published anonymously or under whimsical names. One of these days I’ll pin down its first appearance. Meanwhile, let’s look at those hours of flurry.

Cravats for travel

I don’t know the author of this verse. It appears here, there, and everywhere, referring to Beau Brummell. He didn’t write it, but everybody stole it without attribution, as often happened/happens. Still, a great deal was published anonymously or under whimsical names. One of these days I’ll pin down its first appearance. Meanwhile, let’s look at those hours of flurry.Many readers are familiar with Cruikshank’s 1818 illustration from Neckclothitania (top left). Like many publications of the time about neckwear, it’s a combination of fact and satire.

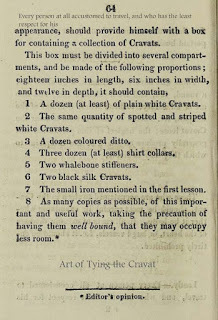

However, it turns out that another book on neckcloths became an international bestseller. The Art of Tying the Cravat : demonstrated in sixteen lessons, including thirty-two different styles ... (the title’s longer than the book), appeared first in France, then Italy, then England, apparently by different authors. But the names seem to have been a joke: “Baron Emile de l’Empesé, Conte della Salda, and H. LeBlanc, which translate respectively as Baron Starch, Count Starched, and H. White or Starch,” as Sarah Gibbings points out in her fascinating tome, The Tie: Trends and Traditions 1990. Nonetheless, the Art of Tying the Cravat is charming. And informative. I recommend taking a look at it.

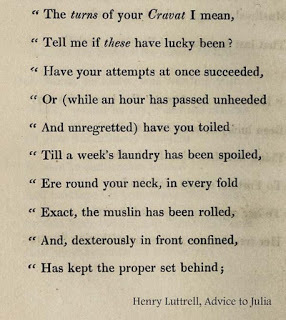

Advice to Julia

excerpt

Advice to Julia

excerpt

You can also find a number of Youtube videos, but none struck me as satisfactory. For a good visual, I suggest you take a look at MY Mr Knightley: Tying a Cravat , at the blog Tea in a Teacup .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on April 16, 2018 21:30

From the Archives: How Many Handsewn Stitches in an 18thc Man's Shirt?

Susan reporting,

Since Loretta's last post featured men's neckcloths, it seemed like a fine time to share this post from the archives about the shirts worn with those neckcloths....

In the 18thc, a man's linen shirt was perhaps the most democratic of garments. Every male wore one, from the King of England to his lowest subjects in the almshouse, and though the quality of the linen and laundering varied widely, the construction was virtually the same.

Contrary to the modern belief that the people of the past were dirty slobs (a bugaboo we NHG are always trying to banish), Georgian men were fastidious about their shirts. Men were judged by the cleanliness of their linen. From laundry records of the time, it's clear that the majority of men changed their shirts daily, and in the hot summer months, it wasn't unusual to change twice a day . This wasn't just a habit of wealthy gentlemen, either. Tradesmen, shopkeepers, and others of the "middling sort" had a good supply of shirts in their wardrobes, a dozen or so on average.

While most of these shirts were purchased from tailors, shirts were one of the few garments that women could make at home for their husbands, brothers, fathers, and sons. Eighteenth century shirts were loose-fitting, geometric garments, all precise squares and rectangles with straight seams. They weren't difficult for the average seamstress to construct - keeping in mind that everything was being sewn by hand before the invention of the sewing machine. The precision of that seamstress's stitching would make them not only more attractive, but also more long-wearing through the rough-and-tumble laundering (no gentle cycle) of the time. But how long would it take to make such a shirt? And how many stitches must be taken in the process?

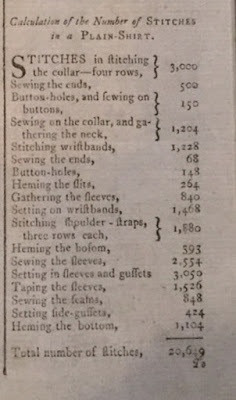

When I was visiting the Margaret Hunter millinery shop in Colonial Williamsburg last month, the mantua-makers (whose seamstresses can make men's shirts just as readily as the tailors) were pondering this exact question. A chart in the July, 1782 issue of The Lady's Magazine, right, calculated the "number of stitches in a plain-shirt", perhaps to provide the amateur seamstresses among their readers with a number to impress the home-stitched shirt's wearer. The Magazine's estimated total was an impressive 20,619 stitches for a man's shirt.

The Margaret Hunter seamstresses took these calculations a step further. Working an average of 30 stitches per minute at a gauge of 10 stitches per inch, it would take approximately eleven and a half hours to stitch a shirt. Of course that doesn't take into account the time for cutting threads, finishing a thread, or threading needles, nor for cutting out the pieces to be sewn, and it also doesn't make allowances for the individual seamstress's speed. While the needles in the Margaret Hunter shop seem to fly, the ladies freely admit that they'd probably be considered slow in comparison to their 18thc counterparts who sewed from childhood.

More about 18thc shirts here and here. Many thanks to Janea Whitacre, mistress of the mantua-making trade, Colonial Williamsburg, for her assistance with this post.

Left: Shirt, maker unknown, linen, probably made in America, c1790-1820. Winterthur Museum.

Photograph © 2014 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Below: Excerpt from The Lady's Magazine, July, 1782.

Published on April 16, 2018 04:02

April 14, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of April 9, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• How much scent was too much for a Victorian lady or gentleman?

• Sophie Blanchard , the first woman to fly solo in a balloon, 1805.

• Online exhibition: American aviatrixes : women with wings.

• Image: Sample book of crochet stitches and patterns.

• " Stupid news " of the 19th century.

• The truth about Johnny Appleseed : he was "a bit of a loon" who died a rich man from planting apples to make hard cider.

• Finding " buried treasure " of the material culture variety on the grounds of an historic 18thc New England house.

• The history of church fans: a quintessential accessory in the American south, and much more in the hands of black women.

• Image: Watercolor painting of George III and Queen Charlotte giving alms to the poor , Maundy Thursday, 1773.

• Medieval Arabic recipes and the history of hummus .

• Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and the war that changed poetry forever.

• One hundred forty-six people, mostly young immigrant women, died a horrific death in New York's Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in 1911.

• Image: Medieval church mermaid , All Saints, Upper Sheringham, Norfolk.

• An African abbot in Anglo-Saxon England.

• Online exhibition featuring "Silence Dogood" - the creation of a teenaged Benjamin Franklin, marking his first published pieces as a journalist.

• Dinner on horseback: a Gilded-Age party for the books.

• Mary Katherine Goddard: the woman who printed the Declaration of Independence.

• In 20thc restaurants, nightclubs, and hotels: check your hat?

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on April 14, 2018 14:00