Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 12

June 7, 2018

Friday Video: Getting Dressed in the 14th Century

Susan reporting,

I've shared the wonderful costume videos by Crow's Eye Productions before ( Dressing an 18thc Lady , Dressing an 18thc Lady: The Busk , and Dressing an 18thc Lady: Pockets. ) Here's their latest, featuring two 14thc woman - a lady, and a servant - dressing for the day. I was struck by how fluid and unstructured these clothes were, and surprisingly modern, too, in their limited color palette.

These videos are the work of Pauline Loven, costume historian, costumer, and heritage film producer, and director Nick Loven. They've recently set up a Patreon page if you'd like to support future videos in the series.

If you receive this post via email, you may be seeing an empty space or a black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on June 07, 2018 21:00

June 6, 2018

Newgate Prison and the Old Old Bailey

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:In June 2017, I sat in two different visitors’ galleries, in two different courtrooms of the Old Bailey, the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, and watched the proceedings. This is not the same Old Bailey I wrote about in Dukes Prefer Blondes , though I noticed similarities in the way the courtroom was laid out, which will be useful the next time I bring criminals into my fiction.

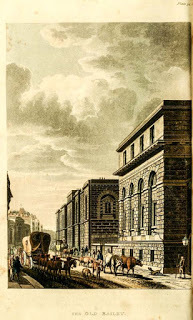

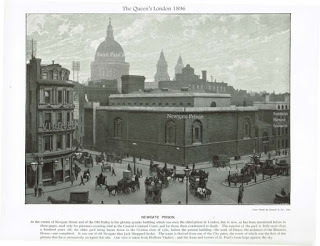

Part of the present building stands where Newgate Prison once did, on the street named Old Bailey. Not many traces of the old building remain. There's a door in the Museum of London, and other bits in the U.S. Since the previous building wasn’t demolished until 1902, though, quite a few photographs are available, along with the Regency-era images by George Shepherd, Thomas Rowlandson, and the like. It took a bit of puzzling to determine from pictures, descriptions, and maps, which was the prison and which was the courtroom, but that might just be my brain malfunction. If you’re looking at an old map, the latter appears as “Session House,” and it ought to be perfectly clear to normal people.

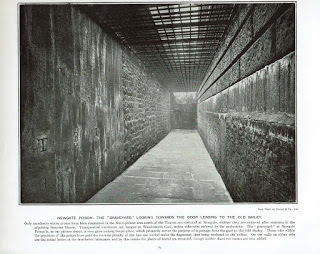

I knew a gloomy walkway connected them. I’d read descriptions, which helped me visualize scenes in the book. But at the time I was writing the story, I couldn’t find images of this passageway. Recently, though, my trusty tome, The Queen’s London, provided the image you see below.

In case one doesn't already feel sufficiently low-spirited at the prospect of being hanged, the passageway will do the trick. It’s the English version of the Bridge of Sighs—that last walk from freedom, possibly from life. Please do read the cheery description under the photo.

You can read the description that accompanies the Ackermann plate (above left) here . Note that this image was done from the other end of Old Bailey, with the Sessions House in front.

Black & white photographs are from my copy of The Queen's London.

Please click on images to enlarge.

Published on June 06, 2018 21:30

June 4, 2018

From the Archives: As Used by Jane Austen: Pins, the Regency Post-It

Susan reporting,

Another oldie but goodie from the archives....

I've written before about the importance of pins in everyday 18th c. life. Straight pins were widely used to fasten all kinds of clothing, from women's bodices to infant's diapers, and also used in hand sewing. Pins were considered so indispensable that when Abigail Adams wrote from colonial Massachusetts to her husband John Adams in Philadelphia in 1775, the one thing she requested was for him to "purchase me a bundle of pins and put in your trunk for me." (Read the rest of the letter here .)

Pins for clothing and sewing, yes. But I hadn't realized that pins were also an essential tool for 18th c. writers. Thanks to (or cursed by, depending on your point of view) computers, most modern writers submit manuscripts electronically. Rewrites and copy edits are all conducted now through the magic of track changes and transmissions. Gone are the days of hauling manuscript boxes to the post office, not to mention pages that bristled with pink "flags", the comments and queries pasted to the edges of pages by editors. I've gotten to the point where the only words on paper I see in the entire process are in the finished book – and the way things are going, that may soon vanish, too.

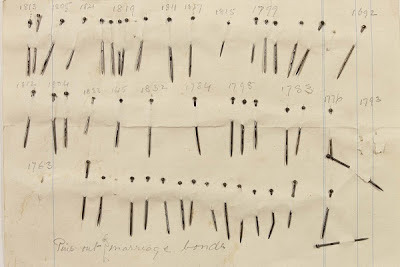

But what did writers do in the days before paper clips and Post-Its? How did an early novelist who was already struggling to make sense of a handwritten manuscript mark revisions and additions? According to the librarians of Oxford's Bodleian Library, the answer is pins – and lots of them. All those notes and insertions and extra copy were handwritten on scraps of paper and pinned in the margin with a straight pin. The pins, above, were all plucked from the library's holdings, and date from 1692 to 1853.

In 2011, the Bodleian acquired a true Jane Austen rarity: the manuscript draft of her abandoned novel, The Watsons. (See here for more about the auction and the staggering realized price, as well as a page of the manuscript itself.) In addition to the clues to cross-outs and rewrites on the draft provide, there were also a wealth of pinned-on additions. For purposes of preserving the manuscript, these pins were carefully removed with their notes, studied, catalogued, and saved – a librarian's scholarly labor of love.

But as a fellow-writer, I like to imagine Jane at work at her small writing table . I wonder: did she use the same pins she used for her clothing, or did she have another stash of pins reserved for writing? Did she keep a pin cushion on the table with a stack of scrap-paper sheets beside her inkwell, prepared and ready to make changes? Or did she tuck them into her sleeve like a hurried seamstress might, keeping them literally at hand when she needed them?

Here is the link to the original article about literary pinning by Christopher Fletcher, Keeper of Special Collections at the Bodleian Library. Thanks to Deb Barnum for first sharing this story with us.

Above: Manuscript pins, c. 1690-1850. Bodleian Library.

Published on June 04, 2018 21:00

June 3, 2018

Fashions for June 1856

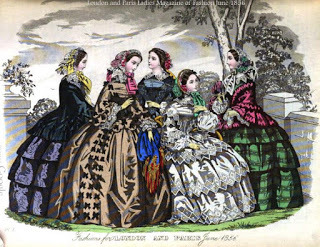

Dresses for June 1856

Loretta reports:

Dresses for June 1856

Loretta reports:By 1856, crinolines were increasing in size, and the complaints rose accordingly.

“A drawing room now looks like a camp. You see a number of bell tents of different colors ... It now fills a brougham, overlapping at the windows, and still in the course of aggrandizement ... Certainly there is a law in fashions if one could but find it out. They have their cycles like storms, and science might calculate the periods of their recurrence. Invention or fancy there is none in fashion, nothing is new. An old thing comes in again. Thus the hoop comes round again in rather an aggravated shape of enormity. But if there is expansion in one quarter, be sure there will be contraction in another ... Thus, while the bonnet has been dwindling away the petticoat has been expanding, engrossing, and pervading all spaces.” —Littell’s Living Age.—No. 639.—23 August, 1856The full entry is worth reading. Just bear in mind the tendency, then and now, for writers and editors (primarily men) to exaggerate and ridicule women's fashion. Photographs—something not available in the earlier part of the century—tell a slightly different story.

Foulard: “A soft, light, washing silk, twilled. Originally, in the [18]20s, of Indian manufacture; later of French. — C. Willett Cunnington , English Women's Clothing in the Nineteenth Century . “Very light and thin silk fabric, woven plain or twilled, printed in conventional style; used for summer dresses.—Louis Harmuth Dictionary of Textiles . “Light silk fabric having a distinctive soft finish and a plain or simple twill weave. It is said to come originally from the Far East. In French the word foulard signifies a silk handkerchief." —Britannica.com

Bretelles: “Strap-shaped trimming”—Cunnington.

Basquine festonné: Basquine: “The extension below the waist-line of the material forming the corsage, either cut in one with it, or applied as separate pieces.” —Cunnington. In this case, the extension is scalloped (festonné).

Taffetas d’éte: Taffeta is “a thin glossy silk of a wavy lustre.” —Cunnington. This apparently is simply a summer taffeta.

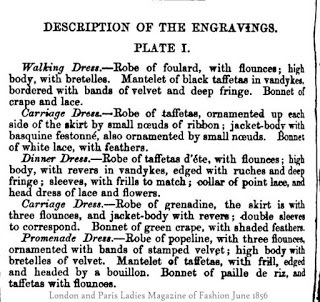

June 1856 Fashions Description

June 1856 Fashions Description

Popeline: This seems to be dressmaker Frenchification of poplin. “1. The real Irish poplin originally had fine organzine warp and a heavier woolen filling, forming cross ribs; 2. Fabrics having fine, cross ribs irrespective of the material they are made of. The better grades are dyed in the yarn; used for coats, dresses, etc. Single poplin has very fine cross ribs, the double poplin is much stouter and has prominent ribs.” Harmuth.

Bouillon: “A puffed-out applied trimming.” Cunnington.

Paille de riz: rice straw

Fashion plates from London and Paris Ladies Magazine of Fashion, June 1856.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on June 03, 2018 21:30

June 2, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of May 28, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The "Flying Mountains", an 18thc roller coaster in Catherine the Great's gardens at Tsarskoe Selo.

• Cleopatra Selene , the only daughter of Cleopatra and Antony, was an important ruler in her own right.

• The modernity of the Victorian men's white dress shirt .

• It's not always the daughter who elopes: rebellious son Philip Jeremiah Schuyler did (and dropped out of college, too) in 1788.

• Image: A 1953 advertisement featuring travel-friendly synthetic fibers .

• Frederick Marryat and the ghostly Brown Lady of Raynham Hall.

• Spalted wood and the lost Renaissance art of intarsia .

• Sweet death: honey and bees in death rituals .

• Image: The 1958 Smart Witch : a "smart bike for smart girls."

• A 15thc English recipe for gingerbread .

• Inked Irishmen: Irish tattoos in 1860s New York.

• How to sublime mercury: reading like a medieval philosopher.

• How Howard Johnson went from one restaurant to a thousand, and back again.

• Knights, Jacobites, and a rebellious duchess: the effigies of All Hallows, Great Mitton.

• Image: Steamboat tourists along the Mississippi in the 1860s carried 11' long scroll-like maps of the river wrapped around spools.

• What made Aaron Burr into AARON BURR?

• Pierre Yantorny, 19th shoemaker who specialized in creating luxurious and fanciful women's shoes. (in Spanish; even if your translator function doesn't quite get it, the photos are worth a look.)

• Earlier royal weddings at Windsor Castle.

• Journeying to the afterlife: the mummy of Djed-djehuty-iuef-ankh.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on June 02, 2018 14:00

May 31, 2018

Friday Video: Being a Regency Lady Ain't Easy

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:There’s quite a bit of variation in the extent to which re-enactors strive for historical accuracy, from hand-sewing, using the tools and methods that would have been used in the given time period—as is done at Colonial Williamsburg, for instance—to the people who create facsimiles or costumes rather than actual historical dress.

This lady makes no bones about the modern methods she uses to achieve a Regency look. But the thing is, she’s just a treat to watch. I think you’ll laugh at least once, maybe several times, as she prepares for the ball. You will also understand how important a lady’s maid was.

YouTube Video by Karolina Żebrowskaska: A Historical Get Ready With Me - 1808 Regency Edition

Image at upper left is a still from the video.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post or the video title.

Published on May 31, 2018 21:30

May 30, 2018

A Scandalous Sketch of Benjamin Franklin with a Lady, c1768

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,It's easy to think of America's Founders only through the images that are left of them, the stoic and often-idealized portraits painted by John Singleton Copley, Gilbert Stuart, and Charles Willson Peale. But regardless of how posterity venerates them, the Founders were a decidedly mixed group in their behavior, beliefs, and morals, as just about any group of white, English-speaking gentlemen from a sprawling colonial society in the 1770s were bound to be.

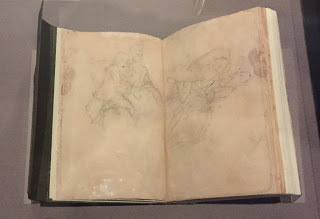

These sketches of Benjamin Franklin (1705-1790) - a writer, inventor, diplomat, printer, Freemason, scientist, and true polymath as well as a Founder - will probably bump those textbook images of him with his kite and printing press right out of your head. I saw the sketchbook on display last fall at the museum of the American Philosophical Society (Franklin was one of the founders of the Society, too, in 1743) as part of their wonderful Curious Revolutionaries: The Peales of Philadelphia exhibition. I've been meaning to feature the drawings in a blog post, and perhaps the last day of the merry month of May is appropriate.

Philadelphia artist Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) was another 18thc man with many interests, and in the course of his long life became a soldier, artist, naturalist, scientist, collector, inventor, politician, museum-owner, and the pater familias of the artistic Peale clan. But in 1767, however, he was still an unknown young portrait painter learning his craft, newly arrived in London to study with fellow-American artist Benjamin West. Like most 18thc travelers, Peale hoped to build his network of connections and possible commissions by calling on other, more established Americans also in London. Among those was Benjamin Franklin, already a celebrated diplomat, philosopher, and bon vivant. Like all artists, Peale also carried his sketchbook with him wherever he went - including social calls.

Here's the APS caption for the above sketch:

While studying art in London, Charles Willson Peale called upon Benjamin Franklin uninvited. Peale accidentally witnessed the well-known Franklin engaging in promiscuous behavior with a lady. Instead of leaving, Peale secretly sketched the scandalous scene for future generations.

There's no record of the amorous lady's name; most likely Peale never learned it himself. He made two sketches on facing pages in in his sketchbook of the couple, right. In the APS records, one is titled as Sketch of Franklin and Lady, lower left, while the one above left is called Scandalous Sketch of Franklin with a Lady.

It's interesting to consider which one he drew first....

Above: Diary Sketch by Charles Willson Peale, c1768, American Philosophical Society.

Published on May 30, 2018 18:04

May 28, 2018

The Regency's Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge 1806

Duke of Cambridge 1806

Loretta reports:

Having recently reported on the present Duke of Sussex and the previous holder of that title , I thought it made sense to look at the man who last held Prince William’s title, Duke of Cambridge.

As in Prince Harry’s case, Prince Adolphus Frederick , the previous Duke of Cambridge (1774-1850), lived during the Regency and Victorian eras, and his life shows some parallels to Prince William’s. Prince Adolphus served in the military, was generally well-liked—including by his father, George III, who wasn’t crazy about his older sons. This royal duke, too, married a beautiful young woman, and had three children

With the death of the Princess Charlotte in 1817, he, like his other brothers, was obliged to find a wife. Of the royal dukes, Peter Pindar wrote:

Agog are all, both old and youngWithin two weeks of his niece’s death, he sent a marriage proposal to the Princess Augusta, the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel’s youngest daughter. She was twenty years old and beautiful.

Warmed with desire to be prolific

And prompt with resolution strong

To fight in Hyman’s war terrific.

“This was the first of the three Royal marriages since Princess Charlotte married Prince Leopold that roused the romantic enthusiasm of the British public* ... “The Duke and Duchess had only to show themselves to be loudly cheered. The first Sunday after their arrival in England they were recognized strolling together in Hyde Park, and were at once surrounded and jostled by a large crowd, cheering and yelling ... On another occasion they were recognized in their carriage outside the famous City jewelers, Rundle and Bridge, and a great crowd came yelling round them, so that it was twenty minutes before their coachman dared move.”

Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, 1818

Their first son, born in March 1819, was christened George, and was in line for the throne until Victoria was born, a few months later.

Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, 1818

Their first son, born in March 1819, was christened George, and was in line for the throne until Victoria was born, a few months later. “And if the English public had good reason to be satisfied with the marriage, so had the Duke of Cambridge. He wrote of himself when he was first married: ‘I really believe that on the surface of the globe there does not exist so happy a Being as myself ... and Heaven grant that I may be deserving of it and not forfeit my happiness by any misconduct.’”He became rather eccentric in later life—among other things, having gone deaf, he sat in front of the church and kept up a running, plainly audible, commentary—and was on very bad terms with Queen Victoria during her early years on the throne. But in a time of rampant anti-Semitism, he remained sympathetic to Jews. He was the only one of George III’s sons who lived within his income. “He was certainly most generous with his time, and equally generous with his money to an almost incredible number of charitable causes.”

Quotations and other information from Roger Fulford’s Royal Dukes .

*Let’s just say that the other couples were rather less attractive.

Images: E. Harding, Duke of Cambridge 1806

Sir William Beechey, Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, 1818

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/co...

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on May 28, 2018 21:30

May 27, 2018

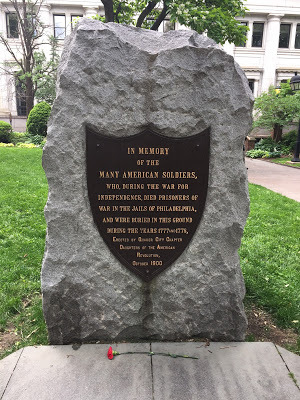

From the archives: Remembering the Soldiers Who Didn't Die in Combat

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,I'm re-running this post, written last year, because the Museum of the American Revolution is repeating their excellent Memorial Day programs, and offering free admission to veterans, active, and retired military for the weekend. They are also once again providing carnations to place at the memorials in nearby Washington Square in Independence National Historical Park. More information here.

Unlike many who live in the Philadelphia area, I haven't spent this weekend - the official kick-off to summer - "down the shore." Instead I returned to the still-new Museum of the American Revolution , one of my favorite places in the city. To my surprise, I had plenty of company. The museum was very crowded with families, a fine and heartening sight to a Nerdy History Person. There's never been a more urgent time in American history to learn about our country's founding, and how the responsibilities that were granted to citizens in 1776 are equally important for us today.

Part of the Museum's observation of the Memorial Day weekend was a quiet reminder that not all those who gave their lives for the Revolution did so in battle. Only a few blocks away from the Museum is the site of a mass grave where Continental soldiers were buried by the British then occupying the city. In 1777, John Adams described his visit to the site in a letter to his wife Abigail:

"I have spent an Hour, this Morning, in the Congregation of the dead. I took a Walk into the Potters Field, a burying Ground between the new stone Prison, and the Hospital, and I never in my whole Life was affected with so much Melancholly. The Graves of the soldiers, who have been buryed, in this Ground, from the Hospital and bettering House, during the Course of the last Summer, Fall, and Winter, dead of the small Pox, and Camp Diseases, are enough to make the Heart of stone to melt away. The Sexton told me, that upwards of two Thousand soldiers had been buried there, and by the Appearance of the Graves, and Trenches, it is most probably to me, he speaks within Bounds....Disease has Destroyed Ten Men for Us, where the Sword of the Enemy has killed one."

Adams was right. While the actual figures for the war are difficult to pin down today, it's estimated that approximately 8,000 Continental soldiers were killed in battle between 1775-1783, while another 17,000 died from diseases such as small pox, typhus, dysentery, and typhoid, often as British prisoners of war in the notoriously unhealthy prison ships.

Today the site of the potter's field lies beneath Washington Square, a tidy, tree-shaded park filled with babies in strollers and well-behaved dogs. In return for a small donation, the Museum offered visitors red and white carnations to take to the Square and place either at the small monument honoring the thousands of unknown soldiers and sailors buried there, or at the larger Tomb of he Unknown Soldier of the Revolution. I did; that's my carnation in the photo, above. I was surprised that there weren't any others, but it was early in the day, and I also suspect that other flowers might have been carried off by children unaware of the significance of their prizes.

No matter. As I stood before the marker, I thought of those long-ago men and boys and likely a few women, too, and of the families and sweethearts who never knew what became of them, beyond that they never returned home. Perhaps there was no "glory" to their deaths, whatever that may mean. Yet still they made the greatest sacrifice possible so that, 240 years later, this place could be a peaceful park filled with children. A single carnation doesn't begin to be enough thanks, does it?

John Adams letter to Abigail Adams, 13 April 1777, from the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to see the entire original letter plus a transcript.

Above: Monument to the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier, Washington Square, Philadelphia. Photograph ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on May 27, 2018 17:00

May 26, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of May 21, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Framing miniature portraits in gold, diamonds, and enamelwork in the 17thc.

• John Wilkes Booth's promptbook (filled with hand-written notes) for Richard III.

• The Georgian landau .

• The feud of the Queen of Spain's physicians, 1566.

• Rainbow-colored beasts from a 15thc Book of Hours.

• Image: Beginning at age 72, 18thc artist Mary Delany created thousands of beautifully detailed flowers from tiny pieces of paper.

• New York's floating chapels helped save 19thc sailors' souls .

• The last derelict 18thc house in Spitalfields , London, is for sale.

• Debunking word myths : the Oxford Dictionary has the real origins of "posh" and "tip."

• For graduation season: 19thc " Rewards of Merit ."

• The world's your oyster - unless you're an Edwardian girl receiving a gift or prize book .

• Image: A pair of faded purple 1880s satin boots that belonged to tragic Tsarina Maria Feodorovna .

• Marvels in marzipan: 19thc royal wedding cakes .

• How work and the factory defined the youth of Mary Laura Triggle, a 19thc working class girl.

• The first and last visits of Frederick Douglass to West Chester, PA, in 1844.

• Forget me not: revealing Victorian mourning customs.

• The Elizabethan country house and the cult of sovereignty.

• Thomas Jefferson shipped a Vermont moose to Paris in 1787.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on May 26, 2018 14:00