Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 8

August 11, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of August 6, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Recreating the lace in a 17thc portrait of Lady Anne Clifford.

• The legendary French drummer boy Joseph Bara of the French Revolution.

• Lifting the lid on plants, poisons, and the power of color (plus how hard it is to kill the beetles needed to make cochineal.)

• Image: Wealthy visitors c1900 to seaside resort at Scarborough, Yorkshire, peer down at women gutting fish for their very hard livelihood.

• The persistence of sixteen-year-old Felicite Kina and her ability to negotiate Napoleonic law to maintain kinship ties.

• A 6thc Lombard warrior buried in northern Italy appears to have worn a knife as a prosthetic weapon in place of his amputated forearm.

• Ann Catley, the feisty diva.

• Image: Gorham Silver ice cream hatchet , c1880.

• The early 20thc pigeons that photographed the earth from above.

• The gravestone of poet John Keats : romancing the stone.

• Itching and scratching: 18thc flea traps .

• The creation of the new London docks in the early 19thc.

• Image: Tiny handmade book created in 1807 by 11-year-old Hannah Coffin .

• How an 18thc clergyman cured a sty on his eye by rubbing it with his tom cat's tail .

• What became of the wild ravens of London?

• William Corder and the Red Barn Murder, 1827.

• How incest became part of the Bronte family story .

• Video: A Roman signet ring is an amazing metal detector find.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 11, 2018 14:00

August 9, 2018

Friday Video: Roller Skating in a Corset and Bustle

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Many readers express dismay at the clothing of the post-Regency 19th century, and how restrictive it seems. There's an assumption that women couldn't do much while wearing corsets and layer upon layer of undergarments. Dress historians and re-enactors, however, have shown us otherwise. For example, some years ago I attended a talk by Astrida Schaeffer , during which she showed photos of Victorian women (whose clothing made it clear they were wearing corsets—not to mention all the other layers) performing various outdoor activities.

My post the other day about bustles drew more of the dismayed comments on social media, e.g., women couldn't do any work in these clothes. And so, naturally, I hunted for evidence that women did not spend all their time lying on sofas in a swoon. I think this video, of a lady skating while wearing a corset and a bustle and the elaborate dress of what seems to be the 1880s, offers a good demonstration. Gina White's even wearing Victorian-era roller skates, which apparently aren't easy to maneuver.

Video:

Roller skating in a bustle dress and a corset Part 1 , Beauty from Ashes, Gina WhiteImage above left is a still from the video. Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post (which will take you to our blog) or the video title (which will take you to YouTube).

Published on August 09, 2018 21:30

Roller Skating in a Corset and Bustle

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Many readers express dismay at the clothing of the post-Regency 19th century, and how restrictive it seems. There's an assumption that women couldn't do much while wearing corsets and layer upon layer of undergarments. Dress historians and re-enactors, however, have shown us otherwise. For example, some years ago I attended a talk by Astrida Schaeffer , during which she showed photos of Victorian women (whose clothing made it clear they were wearing corsets—not to mention all the other layers) performing various outdoor activities.

My post the other day about bustles drew more of the dismayed comments on social media, e.g., women couldn't do any work in these clothes. And so, naturally, I hunted for evidence that women did not spend all their time lying on sofas in a swoon. I think this video, of a lady skating while wearing a corset and a bustle and the elaborate dress of what seems to be the 1880s, offers a good demonstration. Gina White's even wearing Victorian-era roller skates, which apparently aren't easy to maneuver.

Video:

Roller skating in a bustle dress and a corset Part 1 , Beauty from Ashes, Gina WhiteImage above left is a still from the video. Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post (which will take you to our blog) or the video title (which will take you to YouTube).

Published on August 09, 2018 21:30

August 8, 2018

The Lasting Legacy of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Legacies are notoriously fickle things.

They're difficult to create, and even harder to maintain.

Yet one New York woman's legacy still flourishes after more than two centuries. Built on kindness and a genuine concern for the welfare of others, the legacy of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (1757-1854) continues today because the same challenges that faced many children in 1806 unfortunately remain a part of our society in 2017.

During her lifetime, Eliza Hamilton thought of the present, not posterity. Born to privilege and married to Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, she still believed in helping others directly. She brought food, clothes, and comfort to refugees of the French Revolution, and to new widows after yellow fever epidemics. She took in a young motherless girl who'd no place to go, and the child became part of her own family for years. In 1797, she was one of the founders (with her friend Isabelle Graham and her daughter Joanna Graham Bethune) of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children.

When Alexander Hamilton died after his infamous duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, Eliza was grief-stricken, but refused to fade into genteel widowhood. Financial difficulties - Hamilton had left her saddled with many debts - forced her to seek assistance from family and friends to support herself and her children, yet still she continued to help others. Her late husband had begun life as a poor and fatherless child, and orphans were always to hold a special place in her heart - and her energies.

In 1806, Eliza, Isabella Graham, and Joanna Bethune founded the Orphan Asylum Society in the City of New York (OAS). Eliza was named second directress. The OAS began with sixteen orphans, children rescued from a harrowing future in the city's streets or almshouses.

But Eliza and her friends realized that these first orphans must be only the beginning of their mission. In the first years of the nineteenth century, New York had grown into the largest city in America with a population of over 60,000, crowded largely into the winding streets of lower Manhattan. the harbor had made the city a major port, and goods and passengers arrived from around the world.

While some New Yorkers prospered, many more fell deeper into poverty and disease, and it was often the children who suffered most. In greatest peril were children who arrived in the city as new orphans, their immigrant parents having died during the long voyage. Completely alone, these children were often swept into dangerous or abusive situations with little hope of escape.

Eliza and her friends would not abandon them. With each year, the OAS grew larger, and was able to help more children, yet the goals of the OAS never changed. Children were provided not only with food, clothing and shelter, but also education and the skills of a trade so that they cold become independent and successful adults.

In 1821, Eliza was named first directress (president), with duties that ranged from the everyday business of arranging donation for the children in her charge to overseeing the finances, leasing properties, visiting almshouses, and fundraising to keep the OAS growing. With her own sons and daughters now grown, these children became an extended family. She took pride in each of of them, and delighted in their successes, including one young man who graduated from West Point.

She continued as directress until 1848 when she finally, reluctantly, stepped down at the age of 91, yet she never lost interest in the children she had grown to love. When she died in 1854 at the remarkable age of 97 - over fifty years after her beloved Alexander - The New York Times wrote of her: "To a mind most richly cultivated, she added tenderest religious devotion and a warm sympathy for the distressed."

The OAS that Eliza Hamilton helped found continues today. Now known as Graham Windham , it has evolved into an organization that supports hundreds of at-risk children and their families in the New York area. Times have changed - the 19th century's orphans are today's youth in foster care - but the mission remains true to Eliza Hamilton's original goals: to provide each child in their care with a strong foundation for life in a safe, loving, permanent family, and the opportunity and preparation to thrive in school, in their communities, and in the world.

"We serve the children who need us most," says Jess Dannhauser, president and CEO of Graham Windham. "It's a deep personal commitment for us. We don't turn anyone away. These are hard-working, courageous kids who want to make something of themselves and are looking for ways to contribute, and we're constantly adapting to discover the best ways to serve them."

Today - August 9 - marks the 261th anniversary of Eliza Schuyler Hamilton's birthday. Although I completed writing I, Eliza Hamilton over a year ago, I've been thinking a lot about Eliza again lately, especially in a world that seems to have become increasingly selfish and uncaring, with little regard for those - especially children - in need.

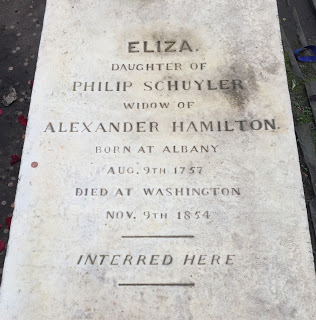

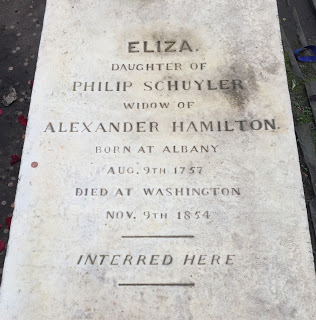

In May, 2017, I visited the churchyard of Trinity Church in Wall Street, where Eliza and Alexander Hamilton are buried side by side. It's become something of a pilgrimage site for fans of Lin-Manuel Miranda's phenomenal musical, and Alexander's ornate tomb in particular is often decked with flowers and other tributes.

On this morning, Eliza's much more humble stone - where she is described only as her father's daughter and her husband's wife, as was common for 1854 - was notably bare, and I resolved to find a nearby florist. Before I did, however, I stopped inside the church itself. Near the door is a box for contributions to Trinity's neighborhood missions, and I realized then that Eliza didn't need another memorial bouquet. Her legacy instead continues in the example of her own selflessness, compassion, and generosity to others. With a whisper to the woman who'd lived long before me, I tucked the money I'd intended for flowers into the contribution box.

Thank you, Eliza, and may your legacy always endure.

Upper left: Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, by Ralph Earl, 1787, Museum of the City of New York.

Right: Mrs. Alexander Hamilton, by Daniel P. Huntingdon, c1845, American History Museum, Smithsonian. Gift of Graham Windham.

Lower left: Grave of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton. Photograph ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, available everywhere.

Published on August 08, 2018 15:18

The Lasting Legacy of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (and a Special Giveaway)

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,I'm revisiting this post today since it's Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton's birthday, but also because I'm offering a special giveaway today only as a way of honoring Eliza and her legacy. Please see below for the details!

Legacies are notoriously fickle things.

They're difficult to create, and even harder to maintain.

Yet one New York woman's legacy still flourishes after more than two centuries. Built on kindness and a genuine concern for the welfare of others, the legacy of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (1757-1854) continues today because the same challenges that faced many children in 1806 unfortunately remain a part of our society in 2017.

During her lifetime, Eliza Hamilton thought of the present, not posterity. Born to privilege and married to Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, she still believed in helping others directly. She brought food, clothes, and comfort to refugees of the French Revolution, and to new widows after yellow fever epidemics. She took in a young motherless girl who'd no place to go, and the child became part of her own family for years. In 1797, she was one of the founders (with her friend Isabelle Graham and her daughter Joanna Graham Bethune) of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children.

When Alexander Hamilton died after his infamous duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, Eliza was grief-stricken, but refused to fade into genteel widowhood. Financial difficulties - Hamilton had left her saddled with many debts - forced her to seek assistance from family and friends to support herself and her children, yet still she continued to help others. Her late husband had begun life as a poor and fatherless child, and orphans were always to hold a special place in her heart - and her energies.

In 1806, Eliza, Isabella Graham, and Joanna Bethune founded the Orphan Asylum Society in the City of New York (OAS). Eliza was named second directress. The OAS began with sixteen orphans, children rescued from a harrowing future in the city's streets or almshouses.

But Eliza and her friends realized that these first orphans must be only the beginning of their mission. In the first years of the nineteenth century, New York had grown into the largest city in America with a population of over 60,000, crowded largely into the winding streets of lower Manhattan. the harbor had made the city a major port, and goods and passengers arrived from around the world.

While some New Yorkers prospered, many more fell deeper into poverty and disease, and it was often the children who suffered most. In greatest peril were children who arrived in the city as new orphans, their immigrant parents having died during the long voyage. Completely alone, these children were often swept into dangerous or abusive situations with little hope of escape.

Eliza and her friends would not abandon them. With each year, the OAS grew larger, and was able to help more children, yet the goals of the OAS never changed. Children were provided not only with food, clothing and shelter, but also education and the skills of a trade so that they cold become independent and successful adults.

In 1821, Eliza was named first directress (president), with duties that ranged from the everyday business of arranging donation for the children in her charge to overseeing the finances, leasing properties, visiting almshouses, and fundraising to keep the OAS growing. With her own sons and daughters now grown, these children became an extended family. She took pride in each of of them, and delighted in their successes, including one young man who graduated from West Point.

She continued as directress until 1848 when she finally, reluctantly, stepped down at the age of 91, yet she never lost interest in the children she had grown to love. When she died in 1854 at the remarkable age of 97 - over fifty years after her beloved Alexander - The New York Times wrote of her: "To a mind most richly cultivated, she added tenderest religious devotion and a warm sympathy for the distressed."

The OAS that Eliza Hamilton helped found continues today. Now known as Graham Windham , it has evolved into an organization that supports hundreds of at-risk children and their families in the New York area. Times have changed - the 19th century's orphans are today's youth in foster care - but the mission remains true to Eliza Hamilton's original goals: to provide each child in their care with a strong foundation for life in a safe, loving, permanent family, and the opportunity and preparation to thrive in school, in their communities, and in the world.

"We serve the children who need us most," says Jess Dannhauser, president and CEO of Graham Windham. "It's a deep personal commitment for us. We don't turn anyone away. These are hard-working, courageous kids who want to make something of themselves and are looking for ways to contribute, and we're constantly adapting to discover the best ways to serve them."

Today - August 9 - marks the 261th anniversary of Eliza Schuyler Hamilton's birthday. Although I completed writing I, Eliza Hamilton over a year ago, I've been thinking a lot about Eliza again lately, especially in a world that seems to have become increasingly selfish and uncaring, with little regard for those - especially children - in need.

In May, 2017, I visited the churchyard of Trinity Church in Wall Street, where Eliza and Alexander Hamilton are buried side by side. It's become something of a pilgrimage site for fans of Lin-Manuel Miranda's phenomenal musical, and Alexander's ornate tomb in particular is often decked with flowers and other tributes.

On this morning, Eliza's much more humble stone - where she is described only as her father's daughter and her husband's wife, as was common for 1854 - was notably bare, and I resolved to find a nearby florist. Before I did, however, I stopped inside the church itself. Near the door is a box for contributions to Trinity's neighborhood missions, and I realized then that Eliza didn't need another memorial bouquet. Her legacy instead continues in the example of her own selflessness, compassion, and generosity to others. With a whisper to the woman who'd lived long before me, I tucked the money I'd intended for flowers into the contribution box.

Thank you, Eliza, and may your legacy always endure.

In honor of Eliza's birthday, I'm asking you to help celebrate in a way that Eliza herself would love. Contribute $15 or more to Graham Windham - the organization that Eliza helped found as an orphanage in 1806 - and I'll send you a copy of my historical novel I, ELIZA HAMILTON , personally autographed for you (or your friend, or your daughter, or your local library) as a special thank-you.

The amazing, talented children of Graham Windham are in need of school supplies to start the school year off right. Each $15 donation will buy a child a brand-new backpack filled with the supplies that they might otherwise not be able to afford. It's easy to help - follow this link to the Graham Windham donation page to make your contribution. Take a snapshot of the bottom of the page that says "Your contribution has been processed," and email it to me (susan@susanhollowayscott.com) along with your mailing address, and how you'd like your copy of I, ELIZA HAMILTON signed. Please make sure your snapshot includes the date. This giveaway is valid only through midnight EST, 8/9/18, and is limited to US addresses.)

Upper left: Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, by Ralph Earl, 1787, Museum of the City of New York.

Right: Mrs. Alexander Hamilton, by Daniel P. Huntingdon, c1845, American History Museum, Smithsonian. Gift of Graham Windham.

Lower left: Grave of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton. Photograph ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, available everywhere.

Published on August 08, 2018 15:18

August 6, 2018

The Bustle in the Mid-1880s

Bustle dress ca 1885

Loretta reports:

Bustle dress ca 1885

Loretta reports:A reader’s comment on my 1885 fashion post , regarding the weight of this type of fashion, sent me in search of more than my vague guess at weight and (in)convenience. While 19th C ladies wore numerous undergarments, I’m focusing on the bustle, since emphasis on the booty is one of the most striking features of the year’s fashions.

From C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington’s The History of Underclothes , I learned that “the name “bustle” was, in the 1880s, considered a little coarse. ‘Tournure’ or ‘dress improver’ was a more ladylike appendage to the lower back.”

The bustle, according to the Cunningtons, “as a separate article from the petticoat with back flouncing, began to return in 1883, in a short form for the walking dress and longer for the evening. By the next year it was either attached to the bodice or the petticoat, or it might be in the form of crescentic steels introduced into the back of the dress itself. By 1885 a horsehair pad, some six inches square and often called a ‘mattress’ was added; the American kind, of wire—‘which answers the purpose much better; was but one of many other varieties. Unlike that used in the 1870s, the bustle of the 1880’s produced a prominence almost at right angles so that it was popularly declared a tea-tray could be comfortably rested on it.”

This image shows the bustles sans accompanying undergarments.

The image at right, also from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gives a better idea of the underpinnings. The bustle is described as “Cotton twill, cotton-braid-covered-steel, and cotton-braid cord.”

1885 undergarments

1885 undergarments

Here is an 1885 cotton twill and wire bustle from about 1885. This bustle shows a slightly different approach, from about the same time. At the V&A is this bustle pad from France. The item appears in Eleri Lynn's Underwear: Fashion in Detail (2014) with this commentary: “By 1880 the bustle had all but disappeared, making a re-emergence around 1883. However, instead of the low drapery of the mid to late 1870s, the new style was sharp and angular, jutting out at right angles to the body. This square bustle pad is made from glazed calico trimmed with silk cord, and fastened with a waist tape. It is stuffed to a very solid shape with straw and would have been worn with several petticoats.” The book, which I recommend, also shows the steel bustle in closeup.

Given the images and the vast amounts of trimmings on the clothing itself, I’m now inclined to agree with the reader that this fashion would be rather heavy and awkward—for us. The ladies, I assume, would have been accustomed, and mightn't have thought of their clothing in that way.

Images: Woman’s 2-piece silk bustle dress, France, c. 1885 , and Bustle and undergarments c 1885, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume and Textiles Department.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed. And, just so you know, if you order a book through one of my posts, I might get a small share of the sale.

Published on August 06, 2018 21:30

August 5, 2018

Winged Lions' Feet, Dolphins, & Horns-of-Plenty: Sofas for a New America, 1800-1830

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Last month I visited the Ten Broeck Mansion , an elegant Federal-style house built in Albany, NY. Built in 1797-98 by General Abraham Ten Broeck and his wife, Elizabeth Van Rensselaer, the house sits high on a hill, overlooking the Hudson River. The mansion is currently the home of the Albany County Historical Association, and most of the rooms are shown decorated to reflect the tastes of the early 19thc owners. I will be writing more about the Ten Broeck Mansion in a future blog post, but today I wanted to feature some of the most interesting - at least to me! - pieces of furniture on display: the sofas. (As always, please click on the images to enlarge them.)

Today we think of a sofa (or couch, or sectional) as the most comfortable piece of furniture in most American homes, a large, soft, and often over-stuffed place for serious lounging. The term "couch-potato" is not to be taken lightly when thinking of modern American sofas.

In the 18thc, however, a sofa was still a rarity in most American homes. Instead most homes featured a variety of chairs that were moved around to suit a room's various purposes (dining, receiving visitors, playing cards), and then placed along the walls of the room when not in use. Lounging wasn't the primary goal. In fact, it probably wasn't even possible in most 18thc chairs.

By the early 19thc, however, American homes were grander and larger, and tastes were changing. The classically inspired French Directoire crossed the Atlantic and became American Directory or American Empire, as exemplified by the work of master American cabinet maker and furniture designer Duncan Phyfe (1768-1854.) The style was considered to possess a particularly patriotic American flavor, incorporating classical design elements much as the American government was modeled on those of Rome and Greece. Acanthus leaves, rosettes, winged lions' paws, and dolphins are ancient motifs, while baskets of fruit, sheaves of wheat, and horns of plenty promised prosperity and abundance for the still-new country.

A sofa in the Directory style became the perfect centerpiece for American parlors, often as part of a matching suite of furnishings. Not only did the sofa display the owners' exquisite taste, but their pocketbook as well. Elaborately carved of imported woods like mahogany and luxuriously upholstered, often in silk, the large and lavish sofa was an expensive status piece.

Alas, tastes in decor are always changing, and what made an imposing statement two hundred years ago is simply too large and unwieldy for modern houses and apartments. With their minimal cushions, these sofas also don't look up to the task of serious Netflix binge-watching, either. But for pure craftsmanship and elegant design, I'll take one of these sofas over a sectional any day.

There are numerous sofas from this period on display in the Ten Broeck Mansion. I think I counted at least a half-dozen, each more imaginative than the last, and in beautiful condition. I'm featuring details of the carving from four of them here.

Many thanks to Karen Giordano, Albany County Historical Association, for her assistance with this post.

Top left: Sofa, c. 1800, carved mahogany. On loan from Gladys V. Clark.

Middle left & right: Sofas, c1810-1830, carved mahogany with upholstery. Both on loan from the Museum of the City of New York.

Bottom right: Sofa, c1810-1830, carved mahogany with upholstery. From bedroom furnished by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Photographs ©2018 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on August 05, 2018 17:21

August 4, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of July 30, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Jane Austen and the Prince Regent: the very first purchase of an Austen novel.

• Charles Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy; or, the Private Companion of Young Married People, 1832, the first popular manual on birth control and the first book on the subject by a physician.

• Gentle Annie Etheridge : no dainty lady on the Civil War battlefields.

• From billets-doux to swiping right: how the language of dating and courtship has evolved.

• Stunningly beautiful example of Shingle Style Architecture: the 1878 Eustis Estate .

• Image: Scorched by the current heatwave, the landscape surrounding Blenheim Palace reveals the ghostly outlines of the 1705 formal gardens.

• Child stealing in Regency England.

• How romanticized photographs and accounts of St Kilda produced a distorted idea of an idyllic Scottish lifestyle on the islands.

• Making the historical personal: reflections on pregnancy and birth .

• Image: An Italian parasol with beaded mermaids, c1800.

• An afternoon in Great Bardfield .

• Can reading make you happier?

• For workers at the Du Pont power mills, the fear of accidental explosions was constant; 228 people were killed at the mills between 1802-1921.

• Image: The wife of an officer killed at Waterloo had his remains boiled, and one of his vertebrae made into this memento mori box .

• When Golden Girls actress Bea Arthur was a Bernice Frankel, US Marine, and served in World War II.

• The 18thc paintings that inspired the costumes in the 2006 movie Marie Antoinette .

• Louise de Lorraine-Vaudemont , 16thc Queen of France.

• Why some 1880s-1920s gravestones are shaped like tree trunks.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 04, 2018 14:00

August 2, 2018

Friday Video: Dressing an 18thc English Gentleman

Susan reporting,

Here's another wonderful fashion history video from the Lady Lever Art Gallery and National Museums of Liverpool, and a companion to this video demonstrating how an 18thc elite woman dressed for her day.

This jaded gentleman is not so much dressing, as being dressed, languidly presenting himself to his valet. Personally, I want to share this video with every copy editor who has queried the word "fall" in relation to 18thc breeches. One picture (or video!) is worth a thousand words.

Thanks to costume historian Pauline Loven and director Nick Loven of Crow's Eye Productions for sharing their latest video with us.

If you received this video via email, you may be seeing an empty space or black box where the video should be. Please click here to view the video.

Published on August 02, 2018 21:00

August 1, 2018

Fashions for August 1885

August 1885 fashions

Loretta reports:

August 1885 fashions

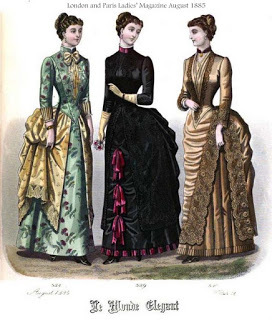

Loretta reports:C. Willett Cunnington, in English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteen Century , expresses no affection for the fashions of this period. “To appreciate the Bustle Era of the ‘80’s, now at its height, it is necessary to recognize that it was accepted as an alternative to the greater horror of the crinoline. The latter would have made the tailor-made walking dress and impossibility whereas with this excrescence behind progress forward was still possible.”

In introducing us to the 1880s, he writes, “The fashions of the ‘80’s were more remote than those of any other decade from modern standards of taste.” According to him, “The principle was strict, that beauty should make no passionate appeal. The epoch was, above all others, anti-anatomical.”

Not quite the way I see it, but every era has its own interpretation of fashion, and we need to put this fashion historian’s observations in the context of his time. The book was published in 1937.

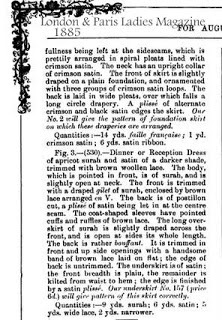

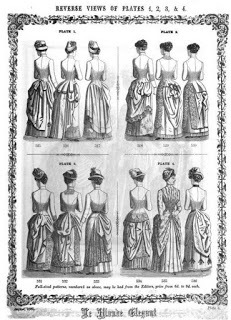

Fashion plates are from the August 1885 issue of The London and Paris Ladies' Magazine of Fashion, which included back views of the dresses, as you see.

Fashion plate description

Fashion plate description

Fashion plate description cont'd

Fashion plate description cont'd

Reverse of fashions

Broché: woven with a raised figure; brocade

Reverse of fashions

Broché: woven with a raised figure; brocadeCrepon: a heavy crepe fabric with lengthwise crinkles

Surah: a soft, twilled silk or rayon fabric

I apologize for the small, blurry description images, and recommend you click on the links for better pictures.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed. And, just so you know, if you order a book through one of my posts, I might get a small share of the sale.

Published on August 01, 2018 21:30