Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 7

September 11, 2018

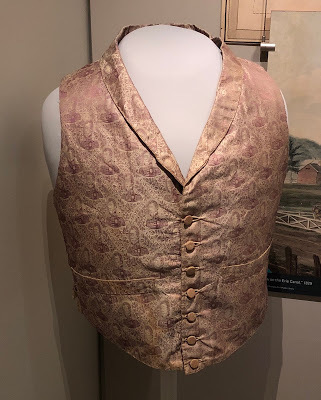

A Silk Vest Honoring the Marquis de Lafayette, c1824

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Yesterday marked the 241st anniversary of the Battle of Brandywine, a pivotal confrontation in the American Revolution between General George Washington and his Continental Army and General Sir William Howe, commander of the British troops. I've written posts about the battle several times before ( here and here . Aside from Brandywine's significance as the largest land battle of the Revolution, it also marked the debut in the war of a young volunteer from France.

An aristocratic idealist with a military background, Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) was only nineteen when he met General Washington in August 1777. Already commissioned by the American Congress as a major general, Lafayette was not at first given troops to command, but instead became a member of Washington's staff. At Brandywine, he saw his first experience in the field; he was shot in the leg, yet still was cited by Washington for his "bravery and military ardor." Lafayette went on to play a key role in the war, not only as an officer and close friend to Washington, but also as a diplomat who helped secure the French ships and soldiers that ultimately tipped the scales for an American victory. He was celebrated as one of the most popular heroes of the Revolution, and remains so to this day. (How many of you began singing Guns and Ships in your head at the mere mention of his name?)

Lafayette is included in a wonderful small exhibition currently on display (through July 9, 2019) at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. Through a well-chosen selection of paintings, maps, and artifacts, The American Revolution: A World War explains how the Revolution was only part of a global shift in the balance of power, war, and conquest that marked the 18thc world. As a Frenchman fighting the British with the American forces and Spanish allies, Lafayette is prominently featured.

But it's not only his wartime exploits that are highlighted. Lafayette's triumphant return to America in 1824 is also included. To quote from the exhibition:

"In 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette returned to the United States at the invitation of President James Monroe. Over fourteen months, he visited all twenty-four states....[President Monroe's invitation came as America] approached the 50th anniversary of its independence. He hoped the general's iconic presence would help rekindle the nation's "revolutionary spirit" and commitment to unity, which seemed to be slipping away. The trip was a smashing success, but it did not moderate the divisive 1824 presidential contest between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson."

Americans celebrated Lafayette's visit with all kinds of souvenirs. Much like modern Americans wear t-shirts printed with the names and faces of their heroes, Lafayette's portrait was emblazoned on ribbons, dresses, and gloves, as well as the vest shown here:

"Hosting the Marquis de Lafayette at a New York banquet, Revolutionary War veteran Matthew Clarkson wore this vest covered with the general's image. During his sojourn, Lafayette attended hundreds of banquets, balls, and celebrations."

Though the Marquis was far too well-bred to record his thoughts about his host, I wonder what it must have been like to sit through a banquet across from a man wearing your face and name all over his chest....

Above left and detail right: Vest worn at banquet for Marquis de Lafayette, 1824-1836, National Museum of American History. Photos ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott.

Lower right: Le marquis de La Fayette en capitaine du régiment de Noailles by Louis Léopold Boilly, 1788, Musée national du château de Versailles. Image ©RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource NY.

Published on September 11, 2018 20:25

September 9, 2018

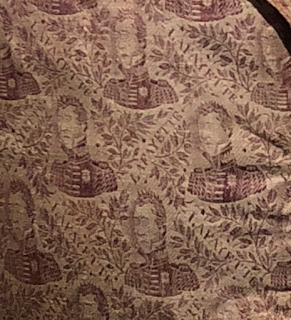

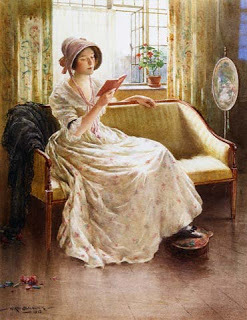

Fashions for Sometime in 1896

Walking Dresses 1896

Loretta reports:

Walking Dresses 1896

Loretta reports:My searches online produced a wealth of 1890s fashion plates. Unfortunately, nobody ever saved the fashion descriptions. However, what turned up in the Met collections is, despite the lack of documentation, unexpectedly enlightening.There are descriptions, in French, which I leave you to translate. But what’s unusual about these images is that they appear to be colorized photographs: in other words, these aren’t the stylized images that portray anatomically impossible women’s bodies (please compare and contrast with images in my post of October 2016 ). I imagine some 19th century version of photoshopping went on, but at least these offer a much better sense of the clothing.

La Mode Pratique was a lovely magazine. If you’re interested in 1880s-1920s French fashion, you might want to look at this blog for samples of the pages . At the bottom of the page are links to more posts about the magazine.

Evening Dress 1896

Evening Dress 1896

Images courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Dresses 1896

Dresses 1896

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on September 09, 2018 21:30

August 22, 2018

Gone Fishin'

Susan & Loretta report:

Susan & Loretta report:We were doing a lot of typing in June ... and July ... and August. But summer’s ending, and it’s time for a break. We’ll be back the second week in September.

Meanwhile, we hope you enjoy these last lazy, hazy, days of summer. For those of you who, like us, have sweltered in ghastly heat and humidity and drowning in local imitations of monsoon season, we wish a change in the weather for something much more agreeable.

See you in next month!

Image: Enrique Estevan y Vicente, Zwei Anglerinnen mit Parasol am Bach (Two female anglers with parasol at the stream) 1880

Published on August 22, 2018 21:30

August 20, 2018

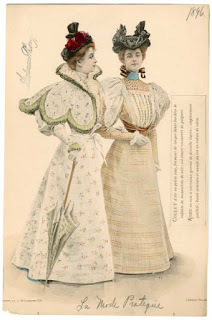

Woman Reads, Wearing a Bonnet Indoors—Really?

Blacklock, A Quiet Read

Loretta reports:

Blacklock, A Quiet Read

Loretta reports:A short time ago, this image appeared on social media, with a question about women wearing hats indoors while reading. This sort of thing leads to my putting on my deerstalker hat and sticking the pipe in my mouth—but not the needle in my arm—and sleuthing.

My collection of historical dress images includes a goodly number of early 19th century ones in which women are indoors, reading, wearing a headdress. They are usually in morning dress, and the headgear is a cap. Some caps are so elaborate, though, that at first glance they seem to be hats, like the English lace cap on the left in this image .

This fashion plate, of a promenade dress , definitely shows a hat (straw), and the woman is holding a book open. Since she’s wearing a rosary and cross, she could be in church, and that could be a prayer book she’s holding. Or not. We often see Regency-era fashion plates of women wearing crosses with evening dress: It’s jewelry.

However, the painting in question is not from the Regency era. It comes from the late 19th/early 20th century, during a period of Regency nostalgia. In the early 1800s, Jane Austen was liked in some quarters, dismissed in others, but essentially no big deal. It wasn’t until the 1880s that she became a rock star. At this time editions of her books illustrated by the likes of Hugh Thomson and C.E. Brock begin to appear, and we start to see a Regency revival in painting. The image in question is from this Regency revival/nostalgia era, when artists like Edmund Blair Leighton, Frederick Morgan, Frédéric Soulacroix, Giovanni Boldinim and many others created their versions of the Regency (and Empire) eras.

Kennington, Lady Reading by a Window c 1900

Looking into this later time period offered a little more enlightenment. William Kay Blacklock’s painting is dated circa 1900. In the late 1800s/early 1900s, I did find a few images of women reading, indoors, wearing hats, like

this one by Frederick Carl Frieseke

, and

this one by James Guthrie

.

Kennington, Lady Reading by a Window c 1900

Looking into this later time period offered a little more enlightenment. William Kay Blacklock’s painting is dated circa 1900. In the late 1800s/early 1900s, I did find a few images of women reading, indoors, wearing hats, like

this one by Frederick Carl Frieseke

, and

this one by James Guthrie

. In conclusion, I can’t altogether explain it, but the image might be historically inaccurate only for the era it’s conveying. Or maybe not. Maybe the lady is sitting in the dentist’s office, waiting her turn. Or maybe she's waiting for her boyfriend to come and collect her for a drive in Hyde Park. Or maybe, as author Caroline Linden suggested, "She's getting ready to go out but just wants to finish one last chapter..." What do you think?

If you've seen other images with this reading-indoors-wearing-a-hat theme, please feel free to share.

My thanks to Lillian Marek for sending me on this very interesting and educational investigation!

Images: William Kay Blacklock, A Quiet Read , possibly circa 1900; Thomas Benjamin Kennington, Lady Reading by a Window ; Gandalf’s Gallery via Wikipedia .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 20, 2018 21:30

August 19, 2018

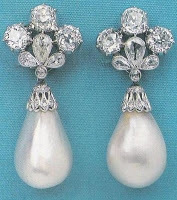

The Queen(s) with the Pearl Earrings

Susan reports:

Susan reports:I've written an earlier blog post about the large pearl that King Charles I wore in one ear. It seems only fair to write about an equally famous pair of pearl earrings worn by his queen, and several others besides. Many legendary jewels of the past have disappeared through wars and revolution, or have been broken up, re-cut, and reset until they bear no resemblance to their original design. But these magnificent earrings, left, have miraculously survived with both pearls and diamonds intact, and with a tantalizing history to match.

The earrings first appear as part of the dower jewels of Marie de' Medici (1575-1642), an Italian princess who left her native Florence to wed the French king, Henry IV (1552-1610). The de' Medici family was old, powerful, and very wealthy, and the jewels that Marie brought with her astonished the French court. At this time, pearls were the most valuable of precious gems, rare accidents of nature. The two almost perfectly matched droplet pearls in the new queen's favorite pair of pendant earrings were of a quality not been seen before in Paris. Other women at the court wore pearl drops (many ladies in 17th c. portraits are shown with them) but most of these pearls were coated glass. Marie's were real, and fit for a queen. She was painted wearing the earrings, right, in 1616 by Peter Paul Rubens.

The earrings first appear as part of the dower jewels of Marie de' Medici (1575-1642), an Italian princess who left her native Florence to wed the French king, Henry IV (1552-1610). The de' Medici family was old, powerful, and very wealthy, and the jewels that Marie brought with her astonished the French court. At this time, pearls were the most valuable of precious gems, rare accidents of nature. The two almost perfectly matched droplet pearls in the new queen's favorite pair of pendant earrings were of a quality not been seen before in Paris. Other women at the court wore pearl drops (many ladies in 17th c. portraits are shown with them) but most of these pearls were coated glass. Marie's were real, and fit for a queen. She was painted wearing the earrings, right, in 1616 by Peter Paul Rubens. When Marie's youngest daughter, the princess Henriette Marie (1609-1699), married the English King Charles I (1600-1649) in 1625, Marie gave the pearl earrings to her as a wedding gift. Henriette, too, was painted many times wearing the earrings, including this portrait of her as a young wife in 1632 by Sir Anthony van Dyck. Her marriage was a happy one, and blessed with many children. But the earrings brought Henriette no luck as the English queen. Her husband's unpopular politics eventually led to a disastrous civil war that cost him his life. Henriette was forced to flee the country in 1644 soon after giving birth to their last daughter, and leaving the baby behind. In exile in France with her sons, she was forced to gradually sell all her jewels first to help support her husband's army, and then, as a widow, to keep herself from poverty. Mementos of happier times, the pearl earrings were among the last jewels to go, finally being purchased by her nephew, the French King Louis XIV (1638-1714) in 1657.

When Marie's youngest daughter, the princess Henriette Marie (1609-1699), married the English King Charles I (1600-1649) in 1625, Marie gave the pearl earrings to her as a wedding gift. Henriette, too, was painted many times wearing the earrings, including this portrait of her as a young wife in 1632 by Sir Anthony van Dyck. Her marriage was a happy one, and blessed with many children. But the earrings brought Henriette no luck as the English queen. Her husband's unpopular politics eventually led to a disastrous civil war that cost him his life. Henriette was forced to flee the country in 1644 soon after giving birth to their last daughter, and leaving the baby behind. In exile in France with her sons, she was forced to gradually sell all her jewels first to help support her husband's army, and then, as a widow, to keep herself from poverty. Mementos of happier times, the pearl earrings were among the last jewels to go, finally being purchased by her nephew, the French King Louis XIV (1638-1714) in 1657. The nineteen-year-old Louis had fallen desperately in love with eighteen-year-old Marie Mancini (1639-1715), the Italian niece of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, the king's primary minister. At first the match was approved both by the cardinal and Louis's widowed mother, and Louis presented the pearl earrings to Marie as his future queen. Marie's portrait, left, shows her wearing the pearls along with flowers in her hair. But politics intruded and the match was broken off, with Louis instead marrying the Spanish Infanta Maria Theresa, and Marie wed to the Roman Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna. But Marie kept the king's pearls, and the earrings were by now so associated with her that they became known by her name, the Mancini Pearls.

The nineteen-year-old Louis had fallen desperately in love with eighteen-year-old Marie Mancini (1639-1715), the Italian niece of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, the king's primary minister. At first the match was approved both by the cardinal and Louis's widowed mother, and Louis presented the pearl earrings to Marie as his future queen. Marie's portrait, left, shows her wearing the pearls along with flowers in her hair. But politics intruded and the match was broken off, with Louis instead marrying the Spanish Infanta Maria Theresa, and Marie wed to the Roman Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna. But Marie kept the king's pearls, and the earrings were by now so associated with her that they became known by her name, the Mancini Pearls.No one is certain whether she left the earrings to one of her children, or sold them herself during her long and tumultuous life. In fact, there is no record of the pearls at all for nearly 250 years, until they appeared at Christie's auction house in New York in October, 1979. There they were sold to a private collector for $253,000, a price that almost seems reasonable considering all the history attached to them. They remain among the most famous jewels ever sold by Christie's.

Now I know that pearls, however beautiful, are inanimate objects, the work of an irritated oyster. But don't you wish these earrings could tell their story, and repeat even a few of the confidences and endearments, promises and secrets once whispered into the ears that wore them?

Published on August 19, 2018 18:00

August 18, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of August 13, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Dr. David Hosack , revolutionary nerd - and physician to both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

• The skeleton suit : sounds scary, but not to the little boys who wore them in the early 19thc.

• "A Gentleman having married a wife made this request to her that she would not ride upon a great dog in the house": gossip from 17thc vicar John Ward.

• Eighteenth century business women and their trade cards.

• Mrs. Bridget "Biddy" Mason was brought to Los Angeles as a slave in 1851; she died free, and one of the city's wealthiest women.

• Image: The Marquis de Lafayette used pre-printed invitations for Monday night suppers; guests included Americans like Adams, Jay, and Jefferson visiting Paris.

• "Anyone can develop a good telephone personality": How to Make Friends By Telephone, a 1950 guide.

• In July, an 18thc white oak from Washington's era fell at Mount Vernon, but most of the stories surrounding the tree were from the Civil War.

• Image: John Adams drew this map of his local taverns in Braintree and Weymouth, MA, in 1760.

• The drowned, submerged prehistoric forests of Lincolnshire.

• Aunt Fanny's school bell , c1920.

• Old Bet, the first elephant brought to America, arrived in Newburyport, MA in 1797.

• Influenced by the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, workhouses built in 19thc England were designed to split up families by putting them in different laboring groups.

• The deadly 1911 heatwave that drove people insane.

• Image: Mona Friedlander and Joan Hughes , the first women to fly military planes in Britain, 1940.

• Julia Child's recipe for a thoroughly modern marriage.

• Benjamin Franklin discovers tofu for America.

• Six historic sites in Britain that survive from the Age of Steam .

• Image: Cat paw-prints preserved in medieval tiles.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 18, 2018 14:00

August 16, 2018

Friday Video: Beautiful Music from an 18thc Harp

Susan reporting,

Here's a wonderfully peaceful way to ease into the weekend: harpist Nancy Hurrell plays a short selection on an 18thc French pedal harp in the collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Made in Paris around 1785 by master luthier and harp-maker Godefroi Holtzman, the harp, right, is an exquisitely beautiful instrument, a work of art even if it didn't make such lovely music. For more information about the harp, please see the museum's page here .

Romance from Sonata in B-flat major (op.13, no. 1), 1775-90, by Jean-Baptiste Krumpholtz, performed by Nancy Hurrell.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing an empty space or black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on August 16, 2018 21:00

August 15, 2018

Votes for Women: The 19th Amendment

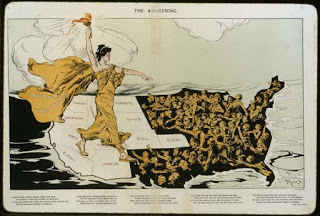

The Awakening 1915

Loretta reports:

The Awakening 1915

Loretta reports:In a few days, we mark a milestone in women’s rights. On 18 August 1920, the state of Tennessee ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. constitution, providing the three-quarters majority needed for adoption.

Here’s what it says:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

"Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

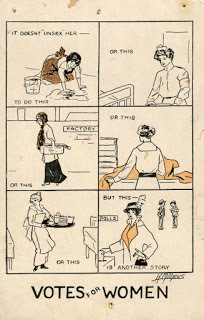

It Doesn't Unsex Her

Senator Aaron A. Sargent of California, whose wife, Ellen Clark Sargent, was a suffragist, first introduced the amendment to Congress in 1878. Yes, it took only forty-two years. And the women’s fight for the right to vote had begun decades earlier. But long, long fights have been the case with a great many other milestones in legislation, like abolishing slavery.

It Doesn't Unsex Her

Senator Aaron A. Sargent of California, whose wife, Ellen Clark Sargent, was a suffragist, first introduced the amendment to Congress in 1878. Yes, it took only forty-two years. And the women’s fight for the right to vote had begun decades earlier. But long, long fights have been the case with a great many other milestones in legislation, like abolishing slavery. We all know the suffragists were ridiculed and abused all the way to the ballot box, but you might want to look at samples of what some people found hilarious, here (let's also ridicule women's fashion while we're at it), here , here , here , here , and here . Note that suffragists are always unattractive, sometimes monstrous. Elderly spinsters appear frequently. Wearing eyeglasses.

Yet a few years later we find images mocking the anti-suffrage side, here , here , here , here , here , and this powerful (and surprising, given the date) image of native American women .

You'll notice that Puck, which had published some of the more infuriating images in this collection, either couldn't make up its mind or finally changed its tune .

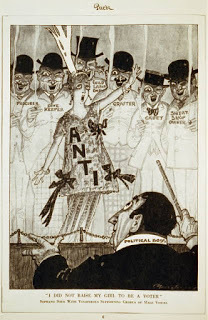

I Did Not Raise My Girl To Be a Voter

Images: Hy Mayer,

The Awakening

, 20 February 1915, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA; Milhouse, Katherine,

It Doesn't Unsex Her

, 1915, via Wikipedia; "I did not raise my girl to be a voter." Soprano solo with vociferous supporting chorus of male voices, 1915, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA .

I Did Not Raise My Girl To Be a Voter

Images: Hy Mayer,

The Awakening

, 20 February 1915, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA; Milhouse, Katherine,

It Doesn't Unsex Her

, 1915, via Wikipedia; "I did not raise my girl to be a voter." Soprano solo with vociferous supporting chorus of male voices, 1915, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA .Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 15, 2018 21:30

August 13, 2018

An 18thc Man's Waistcoat Becomes a 1950s Woman's Vest

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,In our time of fast-fashion and clothing that's made to be disposable, the exquisite clothing of the upper classes in 18thc Europe and America seems stunningly beautiful. Embroidery, embellishment with sequins and faux pearls, silk damasks so artfully woven that they defy modern reproductions: the Georgian era is one big delicious candy-box of precious textiles.

I'm not the only one to think this way, either. These textiles and clothes were so valued that they often had many lives, first being updated and remodeled repeatedly to fit the original owner, and then again by future generations as well. The amount of fabric and the construction (which could easily be unpicked) of most 18thc gowns made them ripe for refashioning. I've written about several of these recycled gowns before, including here , here , and here .

The clothing of 18thc gentlemen, while just as lavish as that worn by the ladies, seldom received the same treatment. This is not only because the men's coats, waistcoats, and breeches were fitted and tailored, providing little fabric for a new project, but also because after 1800 or so, men's clothing took a decidedly more somber turn. There was little interest among men in the 19thc or 20thc to refurbish a spangled pink velvet court suit (except, perhaps, by Liberace.)

But there's an exception to every rule, and the vest shown, left, is the glorious proof. It's currently on display in Fashion Unraveled , a wonderful exhibition at the Museum at FIT through November 17, 2018.

The vest began its clothing-life looking much like the men's waistcoat, right. Made in second half of the 18thc, both waistcoats feature professionally worked embroidery, placed to accentuate the wearer's taste and form. Sometime around 1950, however, a clever seamstress took one of these 18thc men's waistcoats, adapted it to a woman's figure, and created the vest. Preserving the impact of the original embroidery, but shortening the length and adding the darts to create the close-fitting silhouette characteristic of the late 1940s-1950s, the vest would likely have been worn with a full skirt.

Don't know about you, but I'd wear either one (or both!) of these waistcoats now....

Left: Woman's Vest, remodeled c1950 in America, from an 18thc man's waistcoat. Museum at FIT. Photograph ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott.

Right: Man's Waistcoat, c1760-70. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Published on August 13, 2018 21:00

August 12, 2018

The Waltz in Its Early Years

Waltzing 1821

Loretta reports:

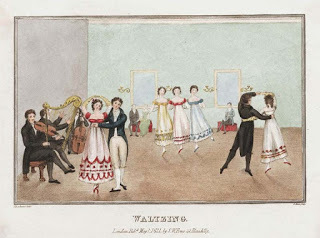

Waltzing 1821

Loretta reports:Some comments on the kinds of physical activities ladies of the 18th and 19th century engaged in led to me to thinking about dancing, and waltzing in particular.

Early in my writing career, I became aware that the waltz had changed over the years, and the early form of the dance wasn’t quite like what we’re familiar with. Images like the ones I’ve posted here don’t look like the style of waltz we’re used to.

According to Elizabeth Aldrich’s From the Ballroom to Hell , “During the first forty years of the nineteenth century, waltzing couples turned clockwise as partners while traveling counterclockwise around the room. This constant spinning, never reversing, could and did produce a feeling of euphoria—or worse, vertigo—that could result in a loss of control.”

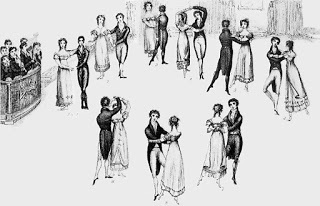

9 Positions of the Waltz 1816

9 Positions of the Waltz 1816

The dance was controversial. Lord Byron disapproved. Yes, really . Others said it was unsuitable for unmarried, highly sensitive, and/or delicate women. I can tell you from my own experience, learning to waltz in a ballroom dancing class, that it is very sexy, and I understood why people disapproved. Also, though I was much younger then, I wasn’t used to ballroom dancing, and one waltz left me a little winded. Even with lots of practice, an entire evening of dancing, in the Regency and Victorian eras, must have provided vigorous exercise.

If you're curious about the precise steps for this era (though they do vary), Carlo Blassis's (trans by R. Barton), The Code of Terpischore, offers a detailed description of the waltz . I have a hard time reading these sorts of instructions, but others of you may be able to picture or re-enact it better.

I wanted to focus on this excerpt, however, which gives a sense of one difference between earlier and later forms of the waltz: “The gentleman should hold the lady by the right hand, and above the waist, or by both hands, if waltzing be difficult for her; or otherwise, it would be better for the gentleman to support the right hand of the lady by his left. The arms should be kept in a rounded position, which is the most graceful, preserving them without motion; and in this position one person should keep as far from the other as the arms will permit, so that neither may be incommoded.” This does correspond with the early 19th century images.

Here is a note from Hints on Etiquette and the Usages of Society; with a glance at Bad Habits (1836): “If a lady waltz with you, beware not to press her waist; you must only lightly touch it with the open palm of your hand, lest you leave a disagreeable impression not only on her ceinture, but on her mind.”

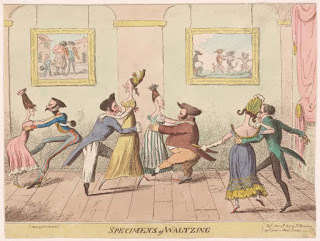

Cruikshank, Specimens of Waltzing 1817

Cruikshank, Specimens of Waltzing 1817

For a more detailed account of the waltz—with lots of lovely images—you might want to read Paul Cooper’s post at Regency Dances.org .

Images: Waltzing 1821, courtesy Lewis Walpole Library Digital Collection; Detail from frontispiece to Thomas Wilson's Correct Method of German and French Waltzing (1816), showing nine positions of the Waltz , via Wikipedia; Specimens of Waltzing , George Cruikshank, 1817-06-04, courtesy New York Public Library.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed. FYI: If you order a book through one of my posts, I might get a small share of the sale.

Published on August 12, 2018 21:30