Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 4

October 26, 2018

Friday Video: Dressing the Women's Land Army During World War II

Susan reporting,

Due to some technical difficulties - looking at you, Comcast - our Friday Video is appearing for Saturday instead this week.

Here's another short video from our friends at CrowsEye Productions . Active during both the First and Second World Wars, the Women's Land Army was a British civilian organization created to fill agriculture jobs with women workers and therefore free more men for military service. While this video does show the kind of uniforms worn by the women in the 1940s, it also gives a glimpse of their lives as country laborers - a life that was likely new to many of the women who were from cities. Don't miss the hand-knitted sweaters and socks, plus some wonderful vintage tractors.

Many thanks to costumer, historian, and producer Pauline Loven for continuing the share these videos with us. From our stats, it's clear you enjoy them as much as we do!

If you received this video via email, you may be seeing an empty space or black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on October 26, 2018 15:45

October 24, 2018

Frankenstein and the Critics

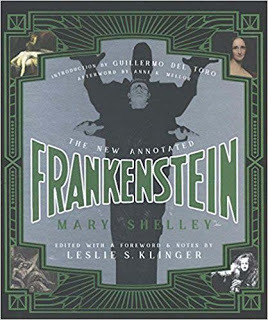

Frankenstein, annotated 2017

Loretta reports:

Frankenstein, annotated 2017

Loretta reports:Mary Shelley’s reviewers had extremely different reactions to Frankenstein.

Following a plot summary, John Croker has this to say:

“Our readers will guess from this summary, what a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity this work presents ... The dreams of insanity are embodied in the strong and striking language of the insane, and the author, notwithstanding the rationality of his preface, often leaves us in doubt whether he is not as mad as his hero."Following samples of the prose style:

“... we take the liberty of assuring [the author] ... that the style which he has adopted in the present publication merely tends to defeat his own purpose, if he really had any other object in view than that of leaving the wearied reader, after a struggle between laughter and loathing, in doubt whether the head or the heart of the author be the most diseased."— Quarterly Review 18 (January [delayed until 12 June] 1818) : 379-385. From the Mary Shelley Chronology and Resource Site, Scholarly Resources, Romantic Circles.

Walter Scott, however, is thrilled:

“So concludes this extraordinary tale, in which the author seems to us to disclose uncommon powers of poetic imagination. The feeling with which we perused the unexpected and fearful, yet, allowing the possibility of the event, very natural conclusion of Frankenstein's experiment, shook a little even our firm nerves ...

It is no slight merit in our eyes, that the tale, though wild in incident, is written in plain and forcible English, without exhibiting that mixture of hyperbolical Germanisms with which tales of wonder are usually told, as if it were necessary that the language should be as extravagant as the fiction. The ideas of the author are always clearly as well as forcibly expressed; and his descriptions of landscape have in them the choice requisites of truth, freshness, precision, and beauty ...

Upon the whole, the work impresses us with a high idea of the author's original genius and happy power of expression ... If Gray's definition of Paradise, to lie on a couch, namely, and read new novels, come any thing near truth, no small praise is due to him, who, like the author of Frankenstein, has enlarged the sphere of that fascinating enjoyment."

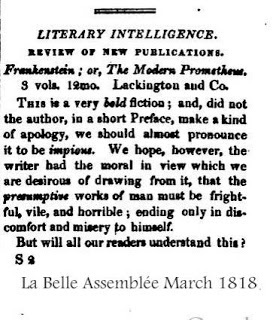

Start of review in La Belle Assemblée

—

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 2 (March 1818)

Start of review in La Belle Assemblée

—

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 2 (March 1818)

His whole review is well worth reading, as are others. You can read them here at the Romantic Circles website.

If you are in New York between now and the last week of January, you might want to stop by the Morgan Library for the exhibition, “It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200.”

Images: Cover of 2017 annotated edition of Frankenstein ; Beginning of La Belle Assemblée review of Frankenstein , Vol. 17, March 1818

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on a caption link will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed. And just so you know, if you order a book through one of my posts, I might get a small share of the sale.

Published on October 24, 2018 21:30

October 22, 2018

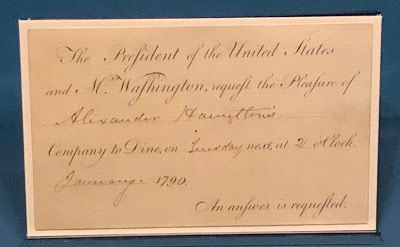

George Washington Requests the Pleasure of Alexander Hamilton's Company to Dine, 1790

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Before there was Evite, before there were texts, before there was even a telephone, hostesses and hosts invited their guests to dine with a hand-written note . If that hostess or host were sufficiently important, influential, or wealthy (or all of those), a specially engraved invitation like the one shown here might be sent. As elegantly worded and beautifully scribed as this invitation appears, the blanks left for the guest's name and other details made them a boon for those with a busy social life.

The card, left, was sent by President George Washington and his wife Martha Washington to invite Alexander and Elizabeth Hamilton to dine at the presidential mansion in January, 1790. Watch out for all the old-fashioned long-form S's that look like F's in the printed part of the invitation. In contrast, the handwritten S at the end of Hamilton's name is quite ordinary. I don't know why Eliza's name wasn't written in as well; perhaps the 18thc version of the modern "plus one" was understood.

At this time, Washington was the country's first president, and still in the first year of his first term; he had taken the oath of office in April, 1789 in New York City, which was then serving as the capital. In early 1790, Washington, his cabinet, and Congress were still creating what would become the federal government, but creating a presidential "style" was important, too. President and Mrs. Washington had to balance their social life between representing the new country in a properly dignified manner, and appearing too elitist or aristocratic, or even monarchical. New rituals like formal dinners and levees were developed, and invitations like this one would have been prized.

The young - they were both in their early thirties - Hamiltons must have been equally prized as guests. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton was a member of Washington's cabinet, and at this time he was considered among the most brilliant and powerful men in the country. In the same month in which this invitation was sent, Hamilton had proposed the first of his economic plans to Congress, his Report on Public Credit. Powerful or not, Hamilton or his wife must have realized the significance of this presidential invitation, and preserved it for posterity.

On loan from the New-York Historical Society, the invitation is currently on display at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia as part of their " Year of Hamilton ." In addition to a special exhibition and interactive playscape called Hamilton Was Here: Rising Up in Philadelphia (opening 10/26), the museum is also hosting special programs and displaying many Hamilton-related pieces - including important letters and documents, portraits, and other artifacts - within their permanent collection over the next year. These will be marked with a special "Hamilton Was Here" label to make Hamilton-hunting easier (and for those of you Hamilfans unable to visit Philadelphia, I'll be sharing more, too.)

Above: Invitation, January, 1790, New-York Historical Society.

Photograph ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on October 22, 2018 21:00

October 21, 2018

The Lunatic Asylum Nightmare

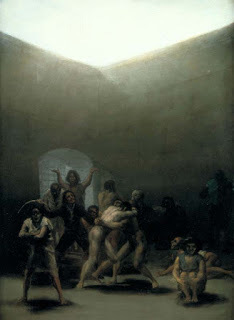

Goya, Courtyard with Lunatics

Loretta reports:

Goya, Courtyard with Lunatics

Loretta reports:The nightmare theme of a sane person being locked up in a lunatic asylum appears in fiction again and again. This is because it touched a chord. For all too many, especially women, this was a grim reality.

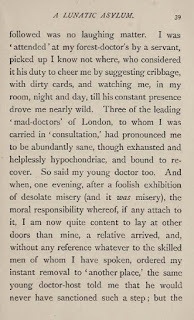

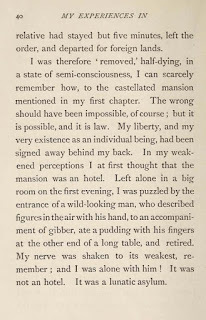

My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum , which I came upon via the Public Domain Review , describes in disturbing detail a man’s experience in the Victorian era. For a woman’s point of view, you might want to look at Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House .

In the fictional world, the theme is prominent in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White .

"I suppose that we most of us...quietly comforted ourselves with the reflection that 'in the nineteenth century' (an expression which is used as a sort of talisman, apparently, like the 'Briton' of Palmerston's day) such things are impossible. It requires a personal experience of their amenities, such as fell to my lot, seriously to believe that the adventures of a novel may be transferred to the pages of an 'article," and be as strange--and true. Villainous conspiracies, for personal motive, to set the lunacy law in motion, are rare enough, I do not doubt. But the law favours them. What is not rare, I doubt even less, is the imprisonment in these fearful places of people who are perfectly sane, but suffering from some temporary disorder of the brain, the most delicate and intricate part of all the mechanism, and the least understood; and if asylums are a sad necessity for the really mad,—and even that I cannot help doubting; for from what I have seen I believe that they require a much more loving and more direction personal supervision than they can get, poor people,--for the nervous sufferers who are not mad they are terrible."—My experiences in a Lunatic Asylum, by a Sane Patient (1879)

Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum

Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum

Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum

Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on a caption link will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed. And, just so you know, if you order a book through one of my posts, I might get a small share of the sale.

Published on October 21, 2018 21:30

October 20, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of October 15, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of favorite links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Rediscovering the black muse s erased from art history.

• A Victorian guide to Cambridge student life.

• Mark Twain liked cats better than people.

• Star-spangled Pierrot and Pierrette costumes from the 1920s.

• How the Romantic poets idolized 18thc Polish freedom-fighter (and veteran of the American Revolution) Tadeusz Kosciuszko .

• Image: Lord Byron's carnival mask .

• The treatment of children in the Garlands Lunatic Asylum , 1862-1914.

• A medieval book that opens six different ways, revealing six different books in one.

• The 19thc British cavalry horse .

• Coach clocks , for telling time on long journeys.

• Infusing life: the first human-to-human blood transfusion , 1818

• Image: Macabre c1815 silver skull opens up to reveal 17thc watch.

• What happens when humans fall in love with an invasive species .

• Land of the Livingstons: historic houses along the Hudson River.

• Maureen Rose , buttonmaker, in a Fitzrovia shop that's in the house where Charles Dickens grew up.

• The royal babies of King George III and Queen Charlotte.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on October 20, 2018 14:00

October 18, 2018

Friday Video: Victorian Photographs in Color

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:When it comes to 19th and early 20th century fashion, as our readers are aware, it’s not all that easy to get a sense of what clothes looked like on real people. Fashion plates offer a simplistic idea of color but tend to be anatomically inaccurate (if not downright bizarre) and flat. Paintings show us color, texture, accessories, and so on, but they tend to be idealized, a sort of Photoshop version of the real person. Photography, once it gets going in the Victorian era, offers a degree of realism (they did doctor photos), but in black and white. Museums show us the actual clothing, but on mannequins often lacking accessories (and very often, underwear).

This video, featuring colorized Victorian and Edwardian photos, helps us get a real sense of real women in a range of clothing. Some of you will recognize at least a few of the women.

40 Amazing Colorized Photos of Victorian and Edwardian Women

Published by Yesterday Today

Image is a still from the video.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post (which will take you to our blog) or the video title (which will take you to YouTube).

Published on October 18, 2018 21:30

October 17, 2018

So Who Wore Round-Ring Pattens in the 18th Century?

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,I wrote earlier this week here about the wavy-ring 18thc pattens - a kind of overshoe with a wooden sole and a metal ring intended to raise the wearer's shoes above wet or otherwise unpleasant terrain - that were being recreated and worn as part of the Historic Trades program at Colonial Williamsburg .

In the course of my discussion about the pattens with apprentice tinsmith Jenny Linn and journeywoman blacksmith Aislinn Lewis (both of whom were involved in the creation, wearing, and research of the replica pattens), we also spoke of a slightly different kind of 18thc pattens. Although the wooden sole and leather straps and laces are much the same, these pattens feature a round metal ring as a support. While the wavy-ring pattens offer plenty of surface area and almost resemble the treads of modern winter boots, the narrower base of the round-ring style would be much more precarious for both balance and walking.

This, however, may be because they weren't intended for walking. Jenny and Aislinn suggested that this type of pattens served an entirely different purpose. In 18thc prints, the round-ring style is usually shown worn by housemaids indoors, and often with a a bucket and mop nearby.

Examples include Piety in pattens, or, Timbertoe on tiptoe, upper left, with a tall maidservant made even taller by very high round-ring pattens. In How are you off for soap, middle right, the ring-bottom pattens are worn by a laundress, whose work would also include splashing soapy water.

The maid of all work in Roberteena Peelena, lower right, not only wears the round-ring style, but has pinned her petticoat up to avoid the wash-water. The maid in the painting A City Shower, lower left, has stepped outside with her bucket, and vigorously twirls her wet mop while poised (rather daintily) on her round-ring pattens.

When the round-ring style appears in prints being worn outdoors in the streets, they seem to be a way that the caricaturist is indicating that the wearer is of a lower or serving class, and a woman who is (in the cruel manner of 18thc caricatures) humorously lower class, unstylish, or down on her luck ( here and here.)

From these sources, it appears that the the round-ring style was worn primarily indoors rather than out, to raise the wearer above soapy water spilled on a wet floor. They may also have served to protect a clean, wet floor from dirty shoes, rather than protecting the shoes from the water. Unfortunately there doesn't seem to be any primary source documentation in the form of letters or journals to explain this further. If anyone has come across such research, I hope you'll share it.

Many thanks to Jenny Lynn and Aislinn Lewis for their assistance with this post.

Upper left: Pattens, leather, wood, & iron rings, c1780-1800, Victoria & Albert Museum.

Upper right: Piety in pattens, or Timbertoe on tiptoe, published by M. Darly, 1773. Walpole Library, Yale University.

Middle left: Detail, How are you off for soap, published by William Elmes, 1816. Walpole Library, Yale University.

Lower right: Roberteena Peelena, the maid of all work by William Heath, 1829, British Museum.

Lower left: Detail, A City Shower by Edward Penny, 1764, Museum of London.

Published on October 17, 2018 21:00

October 15, 2018

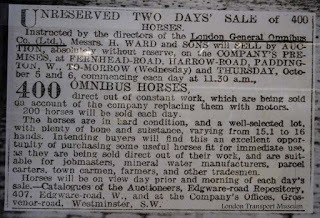

The Omnibus Comes to London

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Last year, during my visit to the London Transport Museum , I encountered a form of public transportation I hadn’t paid much attention to previously.

The omnibus was first introduced in Paris, and it was a Parisian coach-builder, George Shillibeer, who brought the concept to London.

“The route which Shillibeer chose for his first omnibus was from the Yorkshire Stingo at Paddington, along the New Road to the Bank. The New Road was the name by which Marylebone, Euston and Pentonville Roads were then known.

... On the morning of July 4, 1829, Shillibeer's two new omnibuses began to run. A large crowd assembled to witness the start, and general admiration was expressed at the smart appearance of the vehicles, which were built to carry twenty-two passengers, all inside, and were drawn by three beautiful bays, harnessed abreast. The word "Omnibus" was painted in large letters on both sides of the vehicles. The fare from the Yorkshire Stingo to the Bank was one shilling; half way, sixpence. Newspapers and magazines were provided free of charge. The conductors, too, came in for considerable notice, for it had become known that they were both the sons of British naval officers—friends of Shillibeer. These amateur conductors had resided for some years in Paris, and were, therefore, well acquainted with the duties of the position which they assumed. The idea of being the first omnibus conductors in England pleased them greatly, and prompted them to work their hardest to make Shillibeer's venture a success. They were attired in smart blue-cloth uniforms, cut like a midshipman's; they spoke French fluently, and their politeness to passengers was a pleasing contrast to the rudeness of the short-stage-coach* guards—a most ill-mannered class of men. Each omnibus made twelve journeys a day, and was generally full.”

— Henry Charles Moore, Omnibuses and Cabs 1902

Though his omnibus was a success, Shillibeer contended with fierce and often unscrupulous competition and the NIMBY inhabitants of Paddington Green—although “the threatened doom of Paddington Green did not deter the sentimental poke-bonneted young ladies, who resided in the charming suburb, from spending a considerable amount of their time in watching the omnibuses start. In the middle of the day many of them were in the habit of taking a ride to King's Cross and back, for the sole purpose of improving their French by conversing with the conductors.”

Though his omnibus was a success, Shillibeer contended with fierce and often unscrupulous competition and the NIMBY inhabitants of Paddington Green—although “the threatened doom of Paddington Green did not deter the sentimental poke-bonneted young ladies, who resided in the charming suburb, from spending a considerable amount of their time in watching the omnibuses start. In the middle of the day many of them were in the habit of taking a ride to King's Cross and back, for the sole purpose of improving their French by conversing with the conductors.” Anecdotes like this abound, including tales of theft by the paid conductors who soon replaced the gentlemen. Since space doesn’t permit me to quote at length, I recommend you read at least Chapter II of the first part for yourself.

*Short-stage coaches, which had been in existence from the mid-18th century, ran—slowly, expensively, and unpunctually—from the suburbs to the City and the West End.

Images: Photos of Loretta in omnibus at London Transport Museum, View of Exterior London Transport Museum Omnibus, and Announcement Marking the End of the Omnibus Era taken at London Transport Museum, copyright © 2018 Walter M. Henritze III.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on a caption link will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 15, 2018 21:30

October 14, 2018

Recreating (and Wearing) a Pair of 18thc Pattens

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Writing about the past is an ever-changing (and ever-exciting) challenge, and research is one of my absolute favorite parts of the process. I'm always eager to read or hear of new discoveries or fresh perspectives on old ideas, and I never know what may inspire a new character or plot twist.

All of which has brought me back to pattens, a kind of 18thc under-shoe raised up on a metal ring. I've already written a post about them here on the blog.

But while on a recent visit with some of my friends in the Historic Trades program in Colonial Williamsburg , I've come to realize that the subject of pattens is much more complicated.

Fragments of c1770s pattens with a wave-like base, or ring, were discovered in several archaeological digs in Williamsburg, Virginia, and inspired a project at Colonial Williamsburg to recreate them. While pattens would have been the specialized work of a professional patten-maker in 18thc England, in 21stc Colonial Williamsburg they required the skills of several different tradespeople.

Aislinn Lewis, journeywoman blacksmith, made the wavy rings and hardware that held the ring and straps to the sole, and completed the final assembly. Jay Howlett, journeyman artificer and leatherworker, made the leather straps and leather laces. Paul Zelesnikar, journeyman wheelwright, carved the wooden soles from ash. Jenny Lynn, apprentice tinsmith, has worn the finished pattens as part of CW programming. All of them contributed historical research and construction suggestions.

While the fragments were clearly worn in colonial Virginia, no documentation has yet been found to prove that pattens were being made or even sold in the colony at that time. It's probable that the pattens were imported from England, and possibly considered such mundane objects that they weren't listed for sale in newspaper advertisements.

The replica pattens are based not only on the fragments, but also on other, more complete examples that survive in other museum collections. Pattens were inexpensive, workaday footwear that likely didn't have a long life. The flat wooden soles were carved to fit beneath the wearer's shoes, and were held in place by a leather strap that tied across the instep. The metal ring raised the wearer about an inch above the muck of 18thc life, protecting her shoes.

But as Jenny Lynn actually wore the pattens, she discovered a number of things that scholars hadn't realized. First of all, walking in pattens is an acquired skill. Jenny likens it to walking in high-heeled mules. Because there's no back-strap, the wearer's weight must push forward onto the ball of the foot, or she'll walk right out of the soles. An 18thc woman who wore pattens regularly would have been familiar with how best to walk in them, but a certain amount of shuffling must have been unavoidable.

While the assumption has always been that pattens were worn on the notoriously unclean 18thc city streets, Jenny found that this kind of patten would be almost impossible to wear on cobblestone streets, where the rings would slip and tip and lead to sprained ankles and falls. They seem much better suited to the softer surfaces of a more rural life, like an unpaved path or street. Jenny found they work particularly well in mud or wet grass, though if worn by a wealthier woman than a lowly apprentice (sorry, Jenny), the pattens also probably served for making a short journey from a house to a waiting carriage.

The photos here show Jenny (in the blue petticoat) and Aislinn (in the red petticoat) holding the various components to the pattens, as well as close-ups of the soles and rings, and the pattens both on and off the foot. Perhaps my favorite photo is lower right, with the distinctive marks left by the patten-rings mingling with the modern sneaker-treads of CW visitors. The video, below, shows Jenny walking in them.

Many thanks to Jenny Lynn and Aislinn Lewis for their assistance with this post!

All photographs ©2018 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on October 14, 2018 17:48

Recreating (and Wearing) 18thc Pattens

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Writing about the past is an ever-changing (and ever-exciting) challenge, and research is one of my absolute favorite parts of the process. I'm always eager to read or hear of new discoveries or fresh perspectives on old ideas, and I never know what may inspire a new character or plot twist.

All of which has brought me back to pattens, a kind of 18thc under-shoe raised up on a metal ring. I've already written a post about them here on the blog.

But while on a recent visit with some of my friends in the Historic Trades program in Colonial Williamsburg , I've come to realize that the subject of pattens is much more complicated.

Fragments of c1770s pattens with a wave-like base, or ring, were discovered in several archaeological digs in Williamsburg, Virginia, and inspired a project at Colonial Williamsburg to recreate them. While pattens would have been the specialized work of a professional patten-maker in 18thc England, in 21stc Colonial Williamsburg they required the skills of several different tradespeople.

Aislinn Lewis, journeywoman blacksmith, made the wavy rings and hardware that held the ring and straps to the sole, and completed the final assembly. Jay Howlett, journeyman artificer and leatherworker, made the leather straps and leather laces. Paul Zelesnikar, journeyman wheelwright, carved the wooden soles from ash. Jenny Lynn, apprentice tinsmith, has worn the finished pattens as part of CW programming. All of them contributed historical research and construction suggestions.

While the fragments were clearly worn in colonial Virginia, no documentation has yet been found to prove that pattens were being made or even sold in the colony at that time. It's probable that the pattens were imported from England, and possibly considered such mundane objects that they weren't listed for sale in newspaper advertisements.

The replica pattens are based not only on the fragments, but also on other, more complete examples that survive in other museum collections. Pattens were inexpensive, workaday footwear that likely didn't have a long life. The flat wooden soles were carved to fit beneath the wearer's shoes, and were held in place by a leather strap that tied across the instep. The metal ring raised the wearer about an inch above the muck of 18thc life, protecting her shoes.

But as Jenny Lynn actually wore the pattens, she discovered a number of things that scholars hadn't realized. First of all, walking in pattens is an acquired skill. Jenny likens it to walking in high-heeled mules. Because there's no back-strap, the wearer's weight must push forward onto the ball of the foot, or she'll walk right out of the soles. An 18thc woman who wore pattens regularly would have been familiar with how best to walk in them, but a certain amount of shuffling must have been unavoidable.

While the assumption has always been that pattens were worn on the notoriously unclean 18thc city streets, Jenny found that this kind of patten would be almost impossible to wear on cobblestone streets, where the rings would slip and tip and lead to sprained ankles and falls. They seem much better suited to the softer surfaces of a more rural life, like an unpaved path or street. Jenny found they work particularly well in mud or wet grass, though if worn by a wealthier woman than a lowly apprentice (sorry, Jenny), the pattens also probably served for making a short journey from a house to a waiting carriage.

The photos here show Jenny (in the blue petticoat) and Aislinn (in the red petticoat) holding the various components to the pattens, as well as close-ups of the soles and rings, and the pattens both on and off the foot. Perhaps my favorite photo is lower right, with the distinctive marks left by the patten-rings mingling with the modern sneaker-treads of CW visitors. The video, below, shows Jenny walking in them.

Many thanks to Jenny Lynn and Aislinn Lewis for their assistance with this post!

All photographs ©2018 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on October 14, 2018 17:48