Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 14

May 10, 2018

Please Join Me at the Gaithersburg Book Festival, Saturday, May 19

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Next Saturday, May 19, 2018, I'll be appearing at the annual Gaithersburg Book Festival in Gaithersburg, MD (not far from Washington, DC and Baltimore, MD). This is a wonderful all-day festival featuring dozens of bestselling authors, signing and talking about their books - and admission is FREE.

All kinds of books will be represented - fiction, non-fiction, YA, children's books, romance, thrillers, mysteries - plus there will be writing workshops for all ages, literary merchants, and food vendors.

I'll be speaking on a panel called "Putting Eliza Hamilton in the Narrative: Historical Fiction and Hamilton." The panel is scheduled for 12:15 pm in the Edgar Allan Poe Pavilion, and I'll be signing copies of my historical novel I, Eliza Hamilton immediately afterwards. (BTW: If you already have your copy of I, Eliza Hamilton, please bring it along, and I'll be happy to sign it for you.)

Here's the list of featured authors .

Here's the festival schedule.

Here are directions to the Festival.

Hope to see you there! (Especially all you Hamilfans. You know who you are.)

Published on May 10, 2018 21:00

May 9, 2018

The Regency in Color: Werner's Nomenclature

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:The Regency era—both the short “official” (1811-1820) one and the long one (running from, depending on the historian, about 1800 to 1837, when Victoria’s accession to the throne began the Victorian era) was more colorful than a great many people (including me early in my career) believe.

The question about bright colors came up in relation to one of my fashion plate posts : As a commenter remarked, bright colors were indeed available. I also knew where to go to interpret the fanciful names for colors used in fashion: Deb Salisbury's Elephant’s Breath & London Smoke .

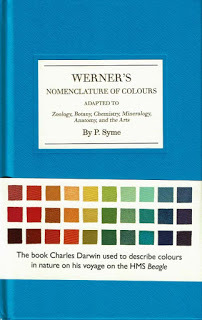

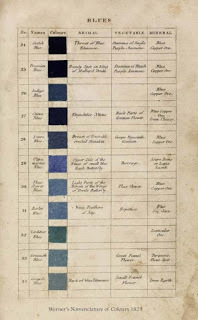

What I didn’t know was that a book with a system for naming colors was created during the Regency. Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours was first published in 1814, with a second edition in 1821. It apparently became a color bible for artists, explorers, naturalists, and others. A new edition, which came out in the U.S. in February of this year, cites Charles Darwin as one of its devotees.

From the introduction:

“A nomenclature of colours, with proper coloured examples of the different tints, as a general standard to refer to in the description of any object, has been long wanted in arts and sciences. It is singular, that a thing so obviously useful, and in the description of objects of natural history and the arts, where colour is an object indispensably necessary, should have been so long overlooked ... To remove the present confusion in the names of colours, and establish a standard that may be useful in general science, particularly those branches, viz. Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Chemistry, and Morbid Anatomy, is the object of the present attempt.”

Blues

You find out more about the book, learn how it came to be, and see some sample pages

here at the publisher’s site

.

Blues

You find out more about the book, learn how it came to be, and see some sample pages

here at the publisher’s site

.And I’m happy to report that the original 1821 edition is online here , complete with the color pages.

Syme, Patrick. Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours: Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts

Since I purchased my copy from a bookseller, no disclaimers are necessary.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on May 09, 2018 21:30

May 7, 2018

From the Archives: What the Mantua-Maker's Apprentice Wore, c. 1775

Susan reporting:

Susan reporting:Since I'm currently mired deep in deadline-itis, I'm sharing another older post from 2012 featuring the clothing of 18thc. working women.

Collections of historic clothing are usually filled with the clothes of the rich and famous, which can give the misguided impression that everyone in the past wore silk and lace. Not quite; but the dress of ordinary folk is more difficult to find (and, for us writers, to imagine), because not much of it survives. Clothing was expensive, and most was worn until it was worn out. Garments were patched and mended and handed down, refashioned (see here ) and recut until there was often nothing left. Even rags were useful, with a gentleman's fine linen shirt eventually ending up as bandages or rags for the paper maker.

All of which is why I especially enjoy seeing what our mantua-maker friends in the Margaret Hunter Shop, Colonial Williamsburg , are wearing to work. While they might be stitching fine silk, for the most part they're dressed as their 18th c. counterparts would have dressed. A shopkeeper's assistant or apprentice in the fashion trades was expected to dress as stylishly as possible within her means, and their clothes often reflected the latest fashions sewn in more modest fabrics. Stylish was good for trade - she was, after all, a walking advertisement for the shop - but not so stylish that she rivaled the customers by dressing above her station. (As always, please click on the photos to enlarge to see details.)

Here Sarah Woodyard is dressed as a mantua-maker's apprentice c.

1775. Her gown is a reproduction of a closed-front English gown with the skirts looped up into two puffs in the back. While this style would have been most fashionable in silk, it's here made up in block-printed cotton. The printed pattern features a meandering vine and tassel motif which would also have been copied from expensive woven silks. The single color would have made the fabric more affordable, too, but the design of the gown – carefully cut to make the most of the cloth's pattern – more than compensates.

1775. Her gown is a reproduction of a closed-front English gown with the skirts looped up into two puffs in the back. While this style would have been most fashionable in silk, it's here made up in block-printed cotton. The printed pattern features a meandering vine and tassel motif which would also have been copied from expensive woven silks. The single color would have made the fabric more affordable, too, but the design of the gown – carefully cut to make the most of the cloth's pattern – more than compensates.While the gown has no costly silk ribbons or trimmings, the apprentice's fine linen cap features not only a wide silk bow, but also extravagant pleating for maximum effect. Her kerchief and apron are also fine white linen, and her white thread stockings and quilted petticoat also contributes to the impression of a neat and tidy assistant. I like the subtlety in the white-on-white textures; if you look closely, you'll see that there's a woven check in her neck kerchief, and diamond-patterned quilting in her petticoat. There's another spot of color in the heart-shaped red pincushion - an essential part of the trade - that hangs ready at her waist, and more in her red ribbon garters. Everything except the stockings was cut and stitched by hand by Sarah herself, just as any good apprentice should.

But it's her shoes that are truly eye-catching. As we've seen before, the 18th c was a glorious time for women's shoes, and these are no exception, made from red silk with yellow leather-covered heels and brass buckles. Sarah is particularly proud of these shoes, since she made them herself while working in CW's shoemakers' shop – see her carving the heels from wood

here

.

But it's her shoes that are truly eye-catching. As we've seen before, the 18th c was a glorious time for women's shoes, and these are no exception, made from red silk with yellow leather-covered heels and brass buckles. Sarah is particularly proud of these shoes, since she made them herself while working in CW's shoemakers' shop – see her carving the heels from wood

here

.Many thanks to Sarah Woodyard for assistance with this post.

All photographs copyright 2012 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on May 07, 2018 21:00

May 6, 2018

The Chaise Longue

Madame Recamier by David 1800

Loretta reports:

Madame Recamier by David 1800

Loretta reports:A reader recently commented:

"This is off topic, but yesterday my family visited the Breakers in Newport. I noticed a lot of chaise lounges in the bedroom and asked the docent how you sat in them. He asked a friend, and they said that napping in bed was considered feeble, or improper so they invented the lounges, but they were only briefly popular."Let me start by staying that Docents/Tour Guides are not all historians, and not everything they say should be taken as gospel. In the course of our travels to historic sites, Susan and I have heard some interesting “explanations” of this and that, which range from Nonsense to Strange But Mostly True to Impeccably Researched.

First, let’s let the Merriam Webster site get the chaise longue vs. chaise lounge terminology out of the way—but please note that, generally, the English went with longue, while Americans leaned on lounge.

Second, the chaise longue was not an invention of the Gilded Age , but was around long before the Breakers was built in 1893. Madame Recamier reclines upon one in the image, upper left, from 1800. The chaise longue at right below appeared in the first volume of Ackermann’s Repository (January 1809). Depending on what you call it—daybed, fainting couch, etc., this type of furniture goes back to the time of the Egyptians, But for now I'm focusing on the 19th century chaise longue.

Third, this piece of furniture had, so far as I can ascertain, nothing to do with napping in bed being feeble or improper. (The Met offers its theory about daybeds, here .) It was often found in the boudoir (though that’s by no means the only place), and was rather more than “briefly popular.” Characters in numerous 19th century novels are lying on chaise longues* or swooning or sitting or dying on them or adding them to a room’s furnishing or throwing a pillow on them or some such.

Chaise Longue January 1809 Ackermann's Repository

The Craftsman, Vol. 29, 1915, offers a

history, with illustrations

, and refers to a “revival.” However, examples of chaise longues appear during the Victorian era as well as the Regency. It's possible, certainly, that one generation or group found them old-fashioned, and another decided they were cool again.

Chaise Longue January 1809 Ackermann's Repository

The Craftsman, Vol. 29, 1915, offers a

history, with illustrations

, and refers to a “revival.” However, examples of chaise longues appear during the Victorian era as well as the Regency. It's possible, certainly, that one generation or group found them old-fashioned, and another decided they were cool again.Here’s an 1805 image from A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration in the Most Approved and Elegant Taste. You can see many Victorian examples here at Carter’s Price Guide to Antiques.

Moving on to the 20th century: Here’s a 1914 image from Elsie de Wolfe’s The House in Good Taste. Here’s a May 1920 image from Illustrated World. And here's an interesting 3-piece version for 1921 from The House Beautiful.

*Chaises longues is also correct for the plural. Dictionaries differ on this. Take your pick.

Images: Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) Portrait of Madame Récamier (1800), Louvre Museum

Chaise longue from Ackermann’s Repository January 1809, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art via Internet Archive.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on May 06, 2018 21:30

May 5, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of April 30, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Dining without men at Delmonico's: the feminist lunch that broke boundaries 150 years ago.

• Body-snatching in 1816: a bad year to be alive, or dead.

• A long-lost morning in a Roundhay Garden : landmark filmmaking and mysterious deaths.

• Something new in 20thc restaurant dining: the introduction of children's menus .

• There's more to Abigail Adams' famous "remember the ladies" letter than is usually acknowledged.

• Dutch patchwork national celebration skirts helped heal a nation after World War Two.

• Image: Wedding gown made from the groom's silk parachute during World War Two.

• A calamitous accident for the Queen of Spain , 1561.

• Ten lesser-known inspirational women from history.

• The curious case of Miss Schwich, a Victorian girl in boy's clothing.

• Image: Annie Oakley, Little Sure Shot.

• Intimate voices of ancient women preserved in letters, permits - and a vendor's license.

• A short history of knitting and activism .

• Made to measure: the tailor's shop at Colonial Williamsburg.

• An 1890s story in clay: Sally Galner and the Saturday Evening Girls.

• Image: The watch and chatelaine of novelist, diarist, and playwright Fanny Burney .

• Victorian tea-gowns .

• Thou art a villain: the changing nature of treason in the Middle Ages.

• How the Victoria & Albert Museum conservators restored a 1730s Chinese fan .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on May 05, 2018 14:00

May 3, 2018

Friday Video: The Last of the Dukes

1st Duke of Wellington-married

Loretta reports:

1st Duke of Wellington-married

Loretta reports:In Romancelandia, we create gorgeous young dukes by the thousands. In real life, as I and others have noted, there were fewer than two dozen, more or less, depending on the time period. And of those few, as I discuss here at RT Reviews , the number who were young, handsome, and single was very small, depending on the year. In the time of my recent stories (1833 & 1835), there were two single dukes, and it was clear they would never marry. Also, they were not young.

6th Duke of Devonshire-lifelong bachelor

The video—thank you, Susan, for sending me the link & letting me do the honors!—is an hour long, but it’s very well done, and if you can set aside some time, I think you’ll find it fascinating.

6th Duke of Devonshire-lifelong bachelor

The video—thank you, Susan, for sending me the link & letting me do the honors!—is an hour long, but it’s very well done, and if you can set aside some time, I think you’ll find it fascinating. No doubt it will raise a great many reactions and questions. A few things I try to remember about the British aristocracy: (1) Even though we have vast economic inequality in the U.S., it’s hard for us Yanks to truly understand that class system and the way people in the UK feel about it; certainly the feelings, positive and negative and in between, exist at a depth I don’t think we can ever fully grasp. (2) Working conditions for the staff were generally hard—in some cases horrifically so—but that was the case for many working people (there and elsewhere), and those grand houses and estates employed and supported a lot of people; also, the conspicuous spending provided work to tradespeople. (3) As in every other walk of life, you have lovely people and you have the other kind.

Those are just a few comments on a big topic. I have a great many more, but I’ll leave it to you to form your own opinions, make your own observations, and so on. For starters, it will be interesting, though, to find out who’s your favorite and least favorite!

Video: The Last Dukes (British Aristocracy Documentary) - Real Stories

Images: Thomas Lawrence, 1st Duke of Wellington , c. 1815-16

Thomas Lawrence, 6th Duke of Devonshire (you can read more about him here )

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on May 03, 2018 21:30

May 2, 2018

From the Archives: What the Maidservant Wore, c1770

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,A reader recently left this comment on one of Loretta's posts: "It is hard to see a woman dressed in some of the outfits of the 18thc or post-1820s doing something as normal as changing a diaper or holding a teething baby. The clothes are for women as objects and not clothes for women who did anything."

I can't answer for the 19thc clothes (I'll leave that for Loretta), but the majority of women in the 18thc did manage to lead active, fashionable lives in the clothing of their times. True, the elaborate dresses worn for court appearances were designed for display rather than practicality, but no one today expects a woman in a $20,000 wedding dress or in haute couture for the red carpet to be tending an infant, either. But the silhouettes and styles created by the very best mantua-makers of the elite class in Georgian times would have gradually filtered down to women of lesser means, who adapted and modified and made the fashions their own. It might have been only a ribbon rosette, or petticoats looped through pocket holes to copy the look of a dress a la polonaise, but fashion was a part of everyday life.

As for the practicality of 18thc clothes: elite women in hoops, stays, and powdered hair danced all night in heeled shoes. They rode to the hunt, made perilous voyages by sea from Europe to America and India, and explored classical ruins. Women wearing stays, ruffled caps, and heels worked in nearly every one of the traditional skilled trades, as blacksmiths, printers, weavers, cooks, bakers, tinsmiths, jewelers, silversmiths, and much more. Women in stays and layers of petticoats followed their soldier-husbands to war, carrying their belongings as they marched behind the army. And while some of these women did have nursery maids (who were also usually wearing those same stays, ruffled caps, and heeled shoes) to help with child-rearing, the majority did not, and did it themselves.

I'll climb down from my soap-box now, and introduce a post from 2012 that echoes these same themes.

We've seen what a stylish British mantua-maker's apprentice might wear in the shop in the 1770s, what a female blacksmith or other laboring woman might wear at her work, and, what, too, a housewife might wear as she went about her day. Now Abby Cox, one of our knowledgable friends from Colonial Williamsburg , shows us what a woman in domestic service might wear. (Her clothes are modern replicas, not 18th c originals, but cut and sewn entirely by hand in true 18th c fashion.)

Uniforms for female servants were a 19th c. innovation. While Georgian-era male servants were often provided with livery, their female counterparts - whether at the top of the servant-ladder as ladies' maids or lowly maids-of-all-work - were expected to provide their own clothing from their meager wages. They were also expected to dress in a manner that was modest, fit for their station, tidy, and clean. Samuel Johnson noted that "women servants. though obliged to be at the expense of the purchasing their own clothes, have much lower wages than men servants, to whom a great proportion of that article is furnished, and when in fact our female house servants work much harder than the male."

Here Abby is wearing an untrimmed English-style gown of a woven striped cotton. The gown has inverted back pleats to shape the waist, and is worn over a plain dark linen petticoat (the under-skirt) and a white linen apron. She has looped her skirts up both to help keep them clean, and to mimic the elaborate skirts of more fashionable gowns - though the effect in the soft cotton fabric lacks the exuberance of poufs of crisp, costly silk.

She also wears white thread stockings, low-heeled buckled shoes, and a linen kerchief tucked around her shoulders. Beneath her gown, her figure is shaped by her stays (corset), which every respectable young woman would wear - see here for more about her stays. Her only indulgence is her cap, ruffled white cotton trimmed with a silk ribbon. While Abby's dress is suitable for a servant, it could be equally worn by a young woman working in a tavern or shop, or simply at home.

Like nearly all 18th c women's clothing, regardless of cost, Abby's gown is pinned closed in front (see detail, left). While men's clothing fastened with buttons and ties, women pinned their clothes together with straight pins; the points of the pins were safely buried in the multiple layers of gown and stays. Pinning was not only a neat finish, but also offered an endless, practical range of adjustments to a woman's changing body.

Photographs by Susan Holloway Scott. Many thanks to Abby Cox for being our maid servant!

Published on May 02, 2018 18:15

April 30, 2018

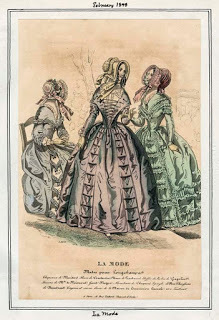

Fashions for May 1843, Supposedly

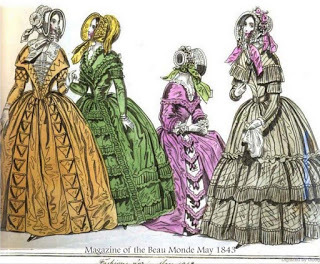

Walking Dresses May 1843

Loretta reports:

Walking Dresses May 1843

Loretta reports:I’ve referred many times to the massive amounts of stealing that went on in fashion magazines (and all other publications). As I was looking for a higher-quality image of the plate in the Magazine of the Beau Monde (at left), I stumbled on a fine example. And what makes it especially interesting is the La Mode fashion was listed for February 1843. However, since the plate from the Los Angeles Public Library online collection was detached from the original magazine, it's possible it was incorrectly dated.

If you will click here (right hand column; please scroll down), you’ll not only learn about the Louis XIII style of sleeve and other fashion trends, but you’ll come upon this charming little note about a style of neckline:

Walking Dresses Feburary 1843

Walking Dresses Feburary 1843

Walking Dresses 1843 Description A general observation that may have been some time back made, by even a common observer, is the lowness of the corsage at the neck, which however it may be, or may not be, claimed to be the business of some to animadvert upon—it is our part simply to notify. This peculiarity still continues. Those who look particularly demure when travelling out of their province to criticise this fashion, and who advocate, or affect to advocate, a puritanism, in such matters, generally forget that their notions are just formed on what they happen to see, or accustomed to see for some time, in their little circle. Had they been used to see, as the common every-day wear, the style of costume worn at the ballet, and patronized by Her Majesty, and our leading nobility, such a tone of criticism would never have been ventured. In many Oriental countries the drapery of the female costume is carried over both extremities of the person, the eyes only being visible in the out door toilette. Who shall judge? The ladies themselves. What shall decide? Taste.

Walking Dresses 1843 Description A general observation that may have been some time back made, by even a common observer, is the lowness of the corsage at the neck, which however it may be, or may not be, claimed to be the business of some to animadvert upon—it is our part simply to notify. This peculiarity still continues. Those who look particularly demure when travelling out of their province to criticise this fashion, and who advocate, or affect to advocate, a puritanism, in such matters, generally forget that their notions are just formed on what they happen to see, or accustomed to see for some time, in their little circle. Had they been used to see, as the common every-day wear, the style of costume worn at the ballet, and patronized by Her Majesty, and our leading nobility, such a tone of criticism would never have been ventured. In many Oriental countries the drapery of the female costume is carried over both extremities of the person, the eyes only being visible in the out door toilette. Who shall judge? The ladies themselves. What shall decide? Taste.Magazine of the Beau Monde image: Walking & Promenade Dresses May 1843 courtesy Google Books. Fashion plate description . La Mode Image , courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Casey Fashion Plates collection.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on April 30, 2018 21:30

April 29, 2018

A c1785 Striped Dress for Walking in a French Garden

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,There are two pink striped dresses in the Visitors to Versailles: 1682-1789 exhibition (now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 29, 2018.) Yet while these two dresses are nearly contemporary, together they show the two very different styles in French women's fashion in the 1770s. I've already written about this lavish robe à la Française, a gown from the 1770s that would have been worn to the most formal events at the palace; consider it a wealthy 18thc French lady's "red carpet look."

The dress shown here dates from about a decade later, 1785-87. This style was called a robe à l'Anglaise, or a dress in the English manner. The robe à l'Anglaise was inspired by British tailoring. Unlike the softly flowing back pleats of the robe à la Française, worn over hoops for sideways volume. the robe à l'Anglaise featured a closely fitted bodice and long sleeves, and a skirt with volume gathered to the back over a false rump or hip pads.

The pinked edges of the ruffled and gathered trim along the skirt offered a feminine contrast to the close-fitting bodice. They would also have drew attention to the wearer's feet with each step - important for a stylish walking-gown.

The fabric is a crisp striped silk with a more tailored air than the floral damask of the earlier dress. The stripes accentuate the seaming and pleats, and also displayed the mantua-maker's skill at neatly mitering those stripes into sharply geometric angles. I also appreciated how the dress was exhibited next to a painting of the gardens at Versailles, juxtaposing the fanning paths of the gardens with the stripes of the dress.

A robe à l'Anglaise like this one would have been worn for day, and the exhibition suggested that it would be perfect for strolling the expansive gardens at Versailles. The shorter skirt would facilitate walking, too, and also show off a stylish pair of heeled silk shoes. A sheer white kerchief of fine muslin or silk would have been tied over the neckline, and an oversized hat or cap and perhaps a parasol would have completed the look. Any of the hats from the painting I shared last week would have been perfect.

Are you ready to go for a stroll?

This dress was also included in an earlier exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the now-legendary Dangerous Liaisons in 2006. The strikingly photographed catalogue is considered one of the very best costume books to feature 18thc clothing; although long out of print, it's available to read or download for free here on the museum's website.

Above: Robe à l'Anglaise, maker unknown, France, 1785-1787, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photographs ©2018 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on April 29, 2018 18:22

April 28, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of April 23, 2018

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served! Our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The art of dressing museum mannequins in rare historic garments.

• The publishing journey of Jane Austen's Persuasion .

• The weathervanes of London.

• The ancient (and continuing) history of red headwear .

• An intimidating library bookplate - and the story behind it.

• Image: Tombstone of Phoebe Hessel 1713-1821 who at age 15 enlisted as a soldier in the 5th Regiment of Foot, disguised as a man to follow her sweetheart.

• Three everyday items invented by women .

• When artist Elisabeth Vigee LeBrun met Emma Hamilton.

• Fascinating historic and natural preservation in the middle of New York City: the complete history of Haarlen Meer in Central Park.

• For Antiques Roadshow fans: a Baroque painting worth millions found in an Iowa storeroom.

• How 1816 was the "year without summer."

• Image: Queen Charlotte's pocket diaries for 1794.

• Cleopatra and the bee-powered vibrator (hint: it's a myth.)

• Gershom Bulkeley: a sensory chymist living in colonial Connecticut.

• What exactly is a Regency-era fanchonette - and how do you make one?

• An 1890s New York City tenement with a dramatic facade - and a history of violence and suffering.

• Working dress , fashion, and textile raw materials in 18thc gardens.

• Image: "I am anxious that it should not be circulated": James Boswell writes the 1792 version of a drunk text.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on April 28, 2018 14:00