Michael Hyatt's Blog, page 40

August 28, 2018

Hobbies for Perfectionists

Learning to Embrace a Hobbyist’s Mediocrity

The Wharton-educated bank executive quits weekend bird-watching excursions after missing a prothonotary warbler (rare orange and yellow-headed songbird) sighting. The tenured physics professor storms out of the kitchen because her batch of gazpacho soup turned out a tad too peppery. First-world problems, to be sure. But they’re also the type of increasingly common complaints hyper-accomplished professionals make when their hobbies and passion projects don’t result in the level of quality and polish they’re accustomed to in the work world.

Many high-achievers find these “shortcomings” tough to stomach because they’ve seamlessly risen to the top strata of American professional society. Yet when it comes to weekend and evening hobbies, they’re sometimes less than perfect. And that’s ok—or at least it should be.

High achievers need not give up on or decline to pursue hobbies just because they won’t be great at them. They ought to get over it and enjoy themselves.

An achievement realm

There’s nothing new about highly successful people in one area tending to think they’ll be good at everything else they try.

Author Stephen Brill explores this theme in his perceptive, if dourly-titled 2018 book, Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America’s Fifty-Year Fall—and Those Fighting to Reverse It. The “winners” in modern American society, Brill writes, feel their achievements have made them immune to failure, in any realm.

Over the last half-century or so, Brill says, meritocrats “were able to consolidate their winnings, outsmart and co-opt the government that might have reined them in, and pull up the ladder so more could not share in their success or challenge their primacy.”

“

High achievers need not give up on or decline to pursue hobbies just because they won’t be great at them. They ought to get over it and enjoy themselves.

—DAVID MARK

That might sound a bit serious as an explanation for why a design engineer with a successful and lucrative practice berates himself over missing a jumper in a weekend basketball pickup game. In the engineer’s mind, he should be able to formulate a solution to the problem. The problem may be as simple as the type of marginal hand-eye coordination that many weekend hoops players suffer from.

But it also helps explain why so many rich guys (and occasionally women) run for high office. Many lose—often handily. These masters-of-the-universes in their own professions find out politics commands a very different set of skills. Usually, of course, the stakes are lower.

Consider the self-flagellating banker, who ventured from his leafy suburban neighborhood to a state park two hours away, only to miss his precious, specific bird-sighting.

Rather than quitting in disgust, he might have realized that spotting beautiful birds is one part of this hobby, but there are many ways to enjoy it. Many bird watchers can spend countless hours learning about various species and types of birds, watching their migratory habits and even photographing or drawing the birds in their natural environment. If they’re looking for a way to reconnect with nature, bird watching is a beautiful way to spend a day.

Or consider the professor who gave up on the culinary arts after a bad batch of soup. She might have observed that one thing necessary to learn with cooking is patience. You can’t be too eager and take food out of the oven early, or it will be undercooked. You have to learn how to wait, and this can help in all other areas of life. Taking up cooking as a hobby can turn you into a more well-rounded person—as can hundreds, even thousands of other potential side interests.

Don’t take yourself so seriously—usually

Not every hobby has the luxury of non-perfection. James Fallows, a Harvard graduate and Rhodes Scholar, served early in his career as a speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter. He migrated into elite journalism, writing for The Atlantic for decades, authoring several books and serving as an NPR commentator, among many other roles. Basically, he’s a member in good standing of the Washington, D.C. journalism-political industrial complex.

Mid-career, Fallows took up piloting. In that type of hobby, there’s little margin for error. Fallows and his wife, Deborah, spent years flying around in a single-engine plane, gathering information on the so-called flyover states. Their work culminated in the 2018 book, Our Towns: A 100,000 Mile Journey Into The Heart of America.

In an August 2018 CNN interview with Christiane Amanpour, Deborah Fallows reflected on safety precautions necessary for their husband-wife team hobby. “Well, Jim is a great pilot and here’s a very conservative pilot and we had some basic rules of only fly in safe conditions,” she said. “Nonetheless, when you’re in a small airplane up there in the sky, weather happens. And when the air traffic controllers say weather, they mean bad weather—or surprises happen. There are birds. There are drones. There are other planes in the sky. There are sudden thunderstorms.”

But for every Fallows-like hobby that can have deadly serious consequences if not approached correctly at all times, there are plenty of lower stakes options.

Beginning skiers in Vermont this past winter might have recognized a familiar face from the George W. Bush-era. Paul Bremer, the veteran U.S. diplomat, worked last winter as a ski instructor at the Okemo Mountain Resort in Vermont.

In his new, seasonal, vocation, though, Bremer told the Boston Globe he’s happy to be out of a high-stress, intensively divisive and political position. “I love it. I absolutely love it,” Bremer said in March 2018. “It’s very rewarding and a lot of fun.”

The Science of Play

Where Win-Win Comes From

As a kid who wasn’t allowed to watch television, the focus of my childhood was play. The games are too many to count. There was, for example, a little girl who lived in mirrorland and would possess me if I accidentally touched that shiny, reflective surface at night. She scared the heck out of my little sisters. Today, they say they knew all along it was a game, but I like to believe I had them fooled.

For better or worse, play changes when you’re an adult. I rarely engage in open-ended, exploratory, pretend-play. I can’t remember the last time I had a truly epic, long-lasting daydream. Even more regimented play, like board games, has become the exception instead of the rule.

Though it would be unrealistic to maintain play as a focus in adulthood, research increasingly points to the benefits of a playful spirit. Mirrorland may just get an encore.

Play and creativity

Mozart enjoyed pranks, Einstein’s most famous photograph includes his arched tongue, and the men who discovered DNA explain their process as playing with molecular models. Struck by the number of exceptionally creative thinkers who were also unusually playful, Dr. Patrick Bateson took to science to determine whether the linkage was more than coincidence.

He developed and released an online survey, asking people a series of questions to measure self-reported playfulness and creativity. In addition, participants were asked to list uses for a jar jam and paperclip. Lists were limited to ten answers. Some people answered only with the conventional use, while others went on to fill up ten possible uses. These lists were then used as a more objective measure of creativity. Both self-reported creativity and the list test corresponded with playfulness.

“

Playfulness is associated with openness and imagination, both essential for creativity.

—ERIN WILDERMUTH

In another study, scientists turned to the biology of creativity. Using magnetic resonance imaging, they found that creative people had more gray matter volume in the right posterior middle temporal gyrus. Though several trait characteristics of creativity were examined, it was an openness to experience that mediated this structural shift.

The results are interesting, but not surprising. Playfulness is associated with openness and imagination, both essential for creativity. Many forms of play are, in and of themselves, creative endeavors..

Play and productivity

Though it wasn’t the attribute that Dr. Bateson studied, Mozart, Einstein, Watson, and Crick have something else in common. They were all incredibly productive, making major contributions to their fields.

Creativity is an important part of human progress and innovation, so it should come as little surprise that playfulness also has productivity benefits. Dr. Mary Ann Glynn and Dr. Jane Webster, two of the pioneers of play research in adults, set about developing an adult playfulness scale in the 1990s. Conducting five studies with over 300 participants, the research team found a positive correlation between playfulness, spontaneity, creativity, and work outcomes.

In part of the study, participants were prompted to complete a sentence construction task. When primed to treat the assignment as work, study participants were less likely to come up with creative answers. Those very same tasks, when approached playfully, resulted in more innovative sentences. The connection between play and productivity was further explored by Dr. René Proyer, who found that his playful students had higher grades than those who were less playful.

“

Becoming playful is a mindset. All it requires is a conscious commitment to approaching the world playfully

—ERIN WILDERMUTH

Social play strengthens relationships

Not all play is social, but social play has the added benefit of strengthening relationships. A 2016 study asked 47 participants to play the mirror game (not to be confused with the mirrorland game) with gender-matched expert players. An Adult Attachment Survey then assessed the quality of attachment achieved during the game. They found that those pairs who had pushed boundaries together had developed the securest attachments. This is in spite of having exhibited lower levels of synchronicity.

What does this mean in terms of play in our lives? Organized sports, board games, and ballroom dancing are a great place to start, but nothing beats open-ended play when it comes to building bonds.

Learning to play

Play takes place without ego, without purpose, and for its own sake. Becoming playful is a mindset. All it requires is a conscious commitment to approaching the world playfully, when appropriate. Your play is your own and it is okay if no one else gets it at first. I have been caught dancing in the supermarket aisles more than once. No one has ever been upset. Confused maybe, but not upset.

Once you’ve confidently infused play into your own life, try taking it social. Embrace openness to new experiences and humility. Humility is essential because initiating play is more than an invitation, it is a reveal. Play is vulnerable. You know that your child will be gleeful, but how might your business partner respond to an infusion of playfulness? Test the waters and find people who value play, but haven’t yet learned to initiate it. You will be doing all parties a favor.

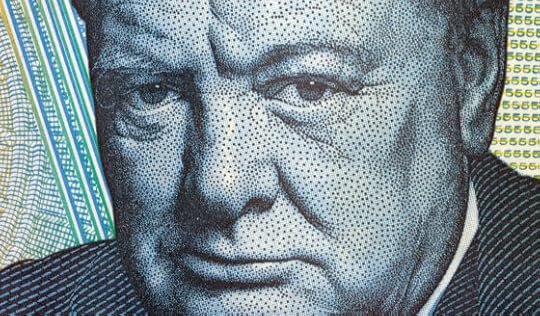

Churchill’s Finest Hobby

Painting Helped Him Beat Depression, and Nazi Germany

Winston Churchill once wrote that “The cultivation of a hobby and new forms of interest is therefore a policy of first importance”. He knew this well. Even as he warned the world about the threat of totalitarian regimes and led Britain during the Second World War, the statesman crafted many of his more than 500 oil paintings, capturing scenes from everywhere he traveled.

For Churchill, taking up brush and easel helped him find respite from the many struggles he had with both his career and his clinical depression. Painting also helped him hone his considerable oratorical skills. He brought the attention to detail he used in his oils to his many speeches.

Churchill’s experience with painting reminds all of us that we should not simply preoccupy our minds with only our careers and personal obligations. Taking up a hobby not only helps you find relief from stress, it can even help you become better in your life at work and home.

Relief from failures and successes

It should be no surprise that Churchill was such a prolific painter. After all, the army officer-turned-politician had written 11 books by the time he turned 40, and authored another 28 (including one on painting) by the time he died in 1965. But painting wasn’t something he did initially out of some great passion. It was to deal with the darkest period in his political career.

By 1915, Churchill’s meteoric rise in politics hit a wall. Overseeing the British Navy, he planned the failed Gallipoli Campaign, costing some 302,000 British and French soldiers their lives, and contributing to the fall of the fall of the wartime government led by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Forced out of his job overseeing the British Navy, then effectively pushed out of politics altogether, Churchill was plagued with doubt and one of his many “Black Dog” episodes of clinical depression.

That’s when painting came into his life. He was first introduced to it by his sister-in-law, Lady Gwendoline Churchill, who handed him a brush and helped him get started with oils. He would then spend time learning from painter Paul Maze as well from other friends who were into the hobby. Churchill proved to be adept at painting landscapes. By 1925, he had won an amateur painting contest and had his work displayed in galleries under various pseudonyms. “Just to paint is great fun,” wrote Churchill in his 1948 book, Painting as a Pastime.

Painting was a relief for Churchill’s troubled mind, especially when dealing with the peaks and valleys of his career, as well as personal tragedies such as the death of his youngest daughter, Marigold, in 1921. For him, “the Muse of Painting” focused his mind on matters other than his career. From his perspective, the only way a man could deal with stress, turmoil and exhaustion was to use other parts of his mind on hobbies unrelated to what is happening in his life.

Building his strengths through a hobby

Taking up painting also benefited Churchill’s long political career in ways even he would only see later on.

He had always been a powerful orator. It was his skills as a public speaker, along with his many books and tales of his adventures in war, which helped him ascend in politics. Over time, his speeches became even more descriptive and powerful, combining both immediate and subtle details. The finale of his “We shall fight on the beaches” speech, given as the Nazis were successfully invading Western Europe, referenced images of the shorelines of both France and Britain and used words that were common to the tongues of both countries, in order to express a unity of purpose between the two nations.

“

The cultivation of a hobby and new forms of interest is therefore a policy of first importance.

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

One reason for the growth of his oratory skills lies in his painting. Details can make or break a landscape. Even the brilliance of a sky depends on adding enough yellow to a blue sky. As Churchill improved his painting skills, his public speaking and writing skills benefited. Declares Churchill’s great-grandson, Duncan Sandys: “Read almost anything he wrote and you can feel as though he is painting a picture before your eyes.”

Churchill himself thought his painting brought other benefits to his work. The struggle of learning how to master oils helped him build patience and endurance, while the effort to focus on trees and flowers helped him become more observant of the events around him. The latter was particularly helpful during his wilderness years of the 1930s, during which he warned his fellow politicians and the public about the threat posed by Hitler’s Nazi Germany, as well in his stewardship of Britain during the war that came.

Time to find your own “Muse”

Churchill was ahead of his time in figuring out the personal and career benefits of taking up hobbies. As a team led by Sarah Pressman of University of California, Irvine, determined in a 2009 study, taking up a hobby can help reduce blood pressure, weight, and body mass. Hobbies can also improve performance at work. By becoming more creative, we gain greater self-control.

Taking up a hobby confers one more benefit that cannot be overstated: the kind of ownership over one’s work product that often isn’t possible in our careers. Success in the workplace is almost always a product of teamwork and your organization’s resource capacity. Mastery over a hobby is something for which you can take sole credit.

As Churchill pointed out, you shouldn’t just take up a hobby willy-nilly. It should be something that you greatly enjoy and also drags you outside of your comfort zone. If you already enjoys physical pursuits such as running, for example, you should probably take up something like woodworking, which exercises both body and mind.

Just as importantly, Churchill advised that once you take up a hobby, you should take it up as seriously as you would learning a second language. After all, as he put it: “To have a second language at your disposal, even if you only know it enough to read it with pleasure, is a sensible advantage.” This means intensively learning, say, how to set up lighting for a portrait photography session, gaining lessons from your failures, and finding as much pleasure in the mastery as you do in the results.

August 21, 2018

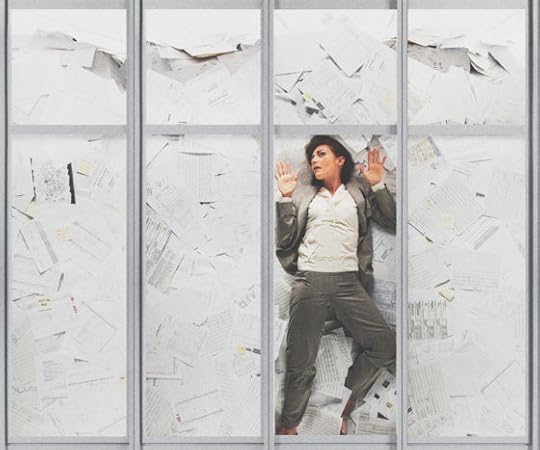

Stop Busywork Now!

Now's the Time to Stop Wasting Time

You already know that busywork does nothing more than create the perception that people are working harder than they really are. In fact, 65 percent of your colleagues surveyed by Havas Worldwide felt that people were simply pretending to be busy.

Nor does busywork make you or your company more productive. What you get instead are weekly meetings that generate more doodles than productive activity, reports that provide little more than clutter for hard drives and desks, and “urgent requests” that suck time away from actual goal achievement.

Yet busywork remains a problem for most workplaces. This is a legacy passed on by management scientists who fostered the kind of micromanaging that leads to busywork. Add in the reality that work cultures often prioritize looking busy over being productive. It is little wonder that busywork continues to plague us.

The consequence of micromanagement

You know all too well the scenes from Office Space in which the coffee-swilling Bill Lumbergh berates Peter Gibbons for forgetting to attach a cover page to his TPS reports, because you have lived it. It can be the monthly “progress report” detailing every task, the software test report that spends more time on inputs than on results, or even the log books law firm partners and associates fill out every day in order to track “billable hours.”

The volumes of paperwork and endless meetings that fill up our days didn’t exist before the 20th century. Then came Frederick Winslow Taylor and so-called scientific management. It was driven as much by distrust of workers as by the legitimate need to more-efficiently pump out more products. Taylor and his disciples thought micromanaging employees and measuring their work was critical to making workplaces efficient. Over time, this approach evolved from time and motion studies to the timesheets, the memos and the meetings we all know so well.

Eventually, it became clear that all that micromanaging and minute tracking didn’t lead to higher levels of productivity. The paperwork, focused primarily on inputs, provided little information on what workers (and ultimately, companies) were achieving and how. The meetings, more about command-and-control than about productive activity, end up crowding out time for real innovation.

Busywork encourages people to appear busy even when what they do achieves nothing. It also begets more meetings, paperwork and activity-tracking, especially as managers and others complain about a lack of productivity. Most importantly, busywork is a symptom of distrust within organizations and does real harm in this age of knowledge workers. As Robert Galford and Anne Siebold Drapeau point out, the inability of institutions and managers to trust employees is a reason why success is often elusive.

When looking busy is most-important

Taylorism may no longer be in vogue. But the paperwork and meetings, along with the distrust and pantomime of work, remain because institutional cultures encourage it.

As human resources consultant Jordan Cohen and Julian Birkenshaw of the London Business School point out, professionals they surveyed admitted that they spend two-thirds of their time writing meaningless reports and shooting off emails (as well as trying to get colleagues engaged in the same tasks to get work done). They are afraid to stop doing busywork because their managers and colleagues reward looking productive over, well, being productive.

Numerous studies have proven that poorly-structured meetings, input-driven reports, and never-ending threads of emails (along with the drive-bys and other interruptions from colleagues and bosses) sap away the precious time needed for the innovation and creativity that can help your company grow. Yet like the aforementioned Lumbergh in Office Space, companies often emphasis those very rituals in the name of being “team players.”

One of the culprits lies in the jockeying for advancement among lower-level executives and middle managers, who often have different priorities than those in the corporate suite and in the cubicles. Their attempts to prove that they are fulfilling the goals set at the top (another form of what I call Corporate Kremlinology) often ends up leading to zealous micromanaging and mundane make-work activities that waste everyone’s time.

A workplace structured for work would disincentivize busywork. Short and quick progress reports would only be issued, let’s say, quarterly—and only about matters that are relevant to performance. Meetings would be limited to one day a week, with those organizing them taking the steps to make them shorter and more focused. Memos should embrace Elmore Leonard’s rule of not providing unnecessary information. Managers would be incentivized to create uninterrupted time for themselves to do their own work—and rewarded for making sure their staffs do the same.

“

The workplace makes it hard to say no. Colleagues and bosses prefer you to say yes even when they realize that the requests are unnecessary.

—RISHAWN BIDDLE

Busy baby steps

Ending busywork starts from the corporate suite and filters all the way down through the enterprise, which can be a slow process. But there are plenty of steps that can be taken to achieve this goal. One way is to empower people to say no to tasks and interruptions that create busywork in the first place.

The workplace makes it hard to say no. Colleagues and bosses prefer you to say yes even when they realize that the requests are unnecessary. Shared calendars make it easy for colleagues to intrude on your day by sending invites to meetings that even they know you don’t need to be on.

Companies can make it easier to say no by requiring everyone to set office hours one day a week during which colleagues and others can make requests. That forces colleagues to think through whether or not their requests are important—and allows everyone to spend less time on tasks that do nothing for innovation, creativity, profit, or success.

Breaking the Addiction to Busy Work

Why It's so Compelling and How to Quit

Hi, my name is Larry, and I’m an addict. I’ve been clean and sober for three years, two months, and eight days. My drug of choice was not alcohol, narcotics, or even nicotine. For decades, I was addicted to fake work.

I spent hours formatting spreadsheets. I immersed myself in fact finding excursions, spending huge chunks of time at bookstores and office supply centers, obsessing over a $50 purchase. I spent countless hours in conference rooms, discussing options. I filed reports with meticulous attention to detail, and I checked email constantly, even after business hours. Worse, I answered every message. I took lunch meetings most weekdays, even some weekends. I looked forward to returning to the office to hear, “There’s someone here to see you.” I was busy, far too busy, doing work that didn’t need to be done.

It all felt so productive. But all this busyness squeezed my most important tasks, my real work, into the margins. Despite all that activity, I was made little progress toward my goals. Yet like a true addict, I returned to my busy work time and again, even as it drained the productivity from me.

The change came when I went into business for myself. As a freelancer, I quickly realized the difference between fake work and real productivity. Real work is anything that advances the mission of your organization. In my case, that was prospecting for clients, negotiating contracts, and placing my butt in the chair to produce the product. Fake work is everything, and I do mean everything, else.

In business terms, real work makes you money, and fake work costs you money. See the difference?

“

By some estimates, fake work accounts for fully half of the activity of most employees.

—LAWRENCE WILSON

By some estimates, fake work accounts for fully half of the activity of most employees. It can be difficult to avoid because, like any addictive substance, it satisfies some inner need. If you’re obsessed with purchasing office supplies, scheduling lunches, and replying to emails that should never have crossed your desk, there is hope. You can break your addiction by understanding these underlying causes of fake work—and taking the cure.

It feels good

Fake work is compelling because it meets a psychological need. First, it satisfies our nearly pathological hunger to prove our worth through activity. Busyness has become the status symbol of our time, and researchers have discovered that people actually aspire to it.

Beyond that, some personality types gravitate to fake work because it fills a particular psychological need for them. For example, the rule abider may spend countless hours ensuring others comply with every jot and tittle of company policy. Or the obsessive organizer may spend an inordinate amount of time arranging their workspace.

The cure here is to measure outcomes, not activity. Ticking 30 items off your list doesn’t prove you’re successful, just busy. Measure success by missional progress, not the number of things you do.

It’s a sneaky way to procrastinate

We all do this. Rather than discipline a problem employee, you write a lengthy email to a customer. When you don’t feel like actually analyzing the quarter’s performance, you make notes on how to improve the reporting procedure. Fake work is not goofing off, exactly. But it does substitute for the more challenging work you may want to dodge.

The cure is to ask, “What am I avoiding?” whenever you find yourself doing something not strictly wasteful but probably unnecessary—like checking email for the second time in an hour. The answer will be the real task you need to accomplish.

It’s fun

Play has no specific outcome. It’s just something we enjoy. Fake work can be a form of play, and we sometimes do it precisely because it doesn’t accomplish something.

Meetings may be the worst culprit here, especially when food is involved. While everyone complains about them, meetings are an opportunity to chit-chat with coworkers, grab a second cup of coffee, and enjoy a respite from the real work that demands so much energy. They can be kind of fun. The same goes for running errands, picking out a new laptop, or shopping for the lowest plane fare. They can be more enjoyable than thinking, writing, or making decisions.

“

Busyness has become the status symbol of our time, and researchers have discovered that people actually aspire to it.

—LAWRENCE WILSON

Play is essential for well-being, but it’s not a substitute for productivity. In a survey of 182 senior managers in a range of industries, 65 percent reported that meetings keep them from completing their own work, and 64 percent said meetings come at the expense of deep thinking. Perhaps worse, 62 percent said meetings miss opportunities to bring the team closer together. In other words, unproductive meetings fail even as play.

When you find yourself dallying on a lackadaisical conference call or a lazy afternoon of internet “research,” ask, “What is this costing me?” That’ll dampen your desire to play at work.

It insulates you from risk

One reason we procrastinate is to avoid risk. If you never have time to start that big project, you never have to figure out how to accomplish it. If you’re always too busy to finish your résumé, you’ll never have to face rejection.

The next time you catch yourself lining up the pencils on your desk or “catching up” with a colleague over lunch, ask, “What am I afraid of?” It might be failure. Or success. Either way, it’ll call out your fake work.

It’s hard to tell from the real thing

The most insidious reason we’re drawn to fake work is that it’s hard distinguish from real productivity. Like a narcotic, which seems to produce real happiness, busy work easily masquerades as true productivity.

Often, the difference is one of degree. As Brent Peterson and Gaylan Nielson point out, “Sometimes real work and fake work can be exactly the same work—just under different circumstances.” An email may require a response, but not a 1,000-word dissertation. Reporting is important, but daily reports are often a waste of time.

“

It all felt so productive. But all this busyness squeezed my most important tasks, my real work, into the margins.

—LAWRENCE WILSON

If you are unable to draw a straight line between what you are doing and the mission of your organization, you’re doing fake work. To inoculate yourself against it, review your goals daily. By starting each day focused on your highest priorities, you can easily distinguish worklike activity from the tasks that will truly drive success in your organization.

Take the pledge

If you’re ready to stop feeling frustrated by how little you accomplish and start making progress on the things that really matter, it’s time to take the pledge. Choose the one item that is your refuge from productivity, and call it what it is: fake work. Then resolve to avoid it, one day at a time.

You can start by standing up, right where you are, and saying, “Hi, my name is ________ and I’m a fake-workaholic. I’ve been focused and productive for one day.”

Meetings Gone Wildly Wrong

How to Recognize and Prevent Fake Meetings

Timothy Wiedman was once a top regional manager for a national retail photofinishing company. He worked hard. Thanks to the company’s “use it or lose it” vacation policy, he made sure to play hard as well.

Wiedman’s only requirements before jetting off to some faraway locale? Delegate critical tasks to subordinates, make his boss aware of his absence, and be sure to only schedule vacations during dead periods. Yet despite adhering to those directives, it was the matter of scheduling that became a point of contention, as Wiedman notes that “the company calendar couldn’t be trusted” and his boss often called last-minute meetings that were “too important to miss.”

On one such occasion, Wiedman lost a nonrefundable deposit at a lush ski resort when his boss required all regional managers to fly to a ritzy hotel for a 90-minute meeting followed by a company dinner—a dinner that was little more than an opportunity for the boss to announce his own promotion.

“Given the cost of airfare, lodging, and a booze-filled celebration that lasted into the wee hours of the morning, this ‘meeting’ cost the company thousands upon thousands of dollars,” Wiedman says.

What fake meetings cost

While extreme, Wiedman’s story is a perfect illustration of fake or useless meetings, when good corporate intentions quickly devolve into exorbitant wastes of time and money. This is the case even without multiple bottles of expensive champagne.

“Let’s assume we have a one-hour meeting with ten people, and each person’s burden rate—the rate the business pays for this person’s work—is $100; then we have just spent $1,000 dollars,” explains Jon M. Quigley, a product development and project management specialist.

“Maintaining a business case for a specific project, or keeping the business viable while spending a great amount of money to produce nothing substantial, narrows the bottom line and can drive a business to closure. That is the worst case [scenario]. The best case is that this business is not able to compete as well as otherwise possible.”

And as Wiedman experienced first-hand, useless meetings don’t just hemorrhage cash. They can also negatively impact the reputation of their organizers. “By calling and engaging in useless meetings, colleagues and leaders will begin to question if the participants know how to prioritize tasks, manage their own workloads, and discern what is important or not,” says career coach Melveen Stevenson. “This causes an erosion of the credibility and performance of the organizer of the meeting, as well as others who actively participate or advocate for them.”

Who called this meeting anyway?

The online meeting company Fuze compiled their findings on useless meetings into one infographic, and the stats are startling:

There are 25 million meetings per day in the U.S., adding up to more than $37 billion per year wasted on unproductive meetings

Middle managers spend 35% of their time in meetings, while upper managers spend 50%

Executives believe a whopping 67% of meetings are failures

Why, then, are fake meetings so prevalent?

“Many leaders schedule or host useless meetings because they are attempting to have their needs met around seeking approval, security, and/or control,” says Emma Kate Roberts, Vice President of Leadership & Transformation at Healthy Companies International and co-author of Conscious: The Power of Awareness in Business and Life.

“These leaders feel insecure in their work environment; meetings are then used to demonstrate to others how much work they are doing or what they are accomplishing. More conscious leaders realize that they can meet these needs from within themselves rather than seeking to have these needs met by others.”

Quigley agrees that insecure leaders often turn to fake meetings, but he offers a different rationale: “I think sometimes the person is not comfortable making a decision and cannot think of a better way to mitigate this lack of comfort. If this is a decision fraught with risk either to the organization or to the individual’s career, he or she may be reluctant to make the decision. To paraphrase, many hands make lite the retribution.”

When bad meetings happen to good teams

Meanwhile, Ada Chen Rekhi, founder, and COO of Notejoy says that even when meetings are called for the right reasons, they can quickly turn unproductive if some basic tenets aren’t met.

“If the required decision makers aren’t in the room, then the meeting clearly can’t achieve any meaningful outcomes” Rekhi says of finalizing the invite list. “These are the meetings that feel useless because there isn’t a viable outcome—resulting in a decision made and a path forward—for the time. It’s often better to postpone a meeting until you can get the right mix of people in a room rather than to assemble the group without the right people.”

Even when the right people there, it can still be a waste of time because the organizers fail to set the right goals or agenda. “This is often the trap that recurring meetings fall into,” Rekhi warns. “They originally had a purpose, but over time, as the purpose shifts or is completed successfully, the meeting lingers. Since it’s still on the calendar, people continue to attend out of habit, even though the meeting lacks a clear agenda or purpose. No decisions are made, nor is meaningful work accomplished.”

Then there is the disturbing lack of follow-up. “Meetings where people identify problems but don’t identify courses of action are often useful from the perspective of information gathering or communal venting. But they don’t result in any action being taken to realize the ideas into reality. At this point, a meeting becomes pretty useless because it’s not clear what the path forward is,” she explains.

Avoiding the trap of fake meetings

Steering clear of fake meetings will take some effort, especially when key team members have a tendency to default to routine. But it’s possible, says Jason Baik, VP of Analytics at Peppercomm.

In keeping with Jeff Bezos’s “two pizza rule,” Baik recommends keeping meeting invite lists as small as possible, save for decision makers. “It’s nice to keep people looped in, but every extra body adds precious minutes of potential questions or discourse,” he says. “Forget the politics and consider who absolutely needs to be there to complete the project.”

He also advocates for strict scheduling. “You may want to schedule an hour, but ask yourself if it can be done in 45 minutes. Cut out the fat by starting the meeting exactly on time, and always end once the objective of the meeting has been met, asking attendees to follow up via email.”

“

Useless meetings don’t just hemorrhage cash. They can also negatively impact the reputation of their organizers.

—ANDREA WILLIAMS

Speaking of objectives, Baik believes that the meeting organizer should lead the meeting and prepare an agenda in advance. “If you don’t know why a meeting is taking place, guess what? You don’t really need the meeting,” he says.

It is this notion of determining whether meetings are actually needed that is the best strategy an organization can employ to fight fake meetings.

“Shift your mindset to adopt a different default mode of communication,” Baik suggests. “I follow Mark Cuban’s advice: Emails should be your go-to; calls should be used when needed; and meetings should be last resorts. If you absolutely must meet face-to-face—dig deep here; I would argue that one isn’t needed most of the time—think very carefully about the following: who’s needed, how long is needed, and what needs to get covered.”

In Defense of Remote Work

Help Your Company Find Its Why

The debate over remote working—what we used to call telecommuting—is endless. It’s also mostly misconceived. Pundits and consultants debate whether it’s a privilege or a right, whether it’s good or bad for productivity, good for morale or not.

The truth is that data and anecdote can be marshaled to support most positions on this issue. In part, this is because “work” is not one thing: building a car, writing code, answering customer-support calls, writing articles about workplace policy—these are all “work,” along with burger flipping, sales, marketing, and on and on.

But even among the types of white-collar jobs most associated with telecommuting, work is multifarious and the considerations about the best way to get it done are complex. Which brings us to the real heart of the remote-working matter: Do you trust your employees?

Send out the scapegoats

If you do, then the answer is straightforward: Trust them to know how best to do their jobs, including where to do them. If you don’t, then remote working isn’t the problem. It’s a scapegoat.

I don’t mean necessarily a scapegoat for underperformance, although it can be that. When IBM, one of the original trailblazers of the telecommute, announced last year that thousands of remote workers would have to start coming to the office, observers were quick to note that the company had seen 19 straight quarters of revenue declines.

Likewise, Marissa Mayer’s ill-fated attempt to turnaround Yahoo included a clamp-down on remote work. Of course, Mayer steered clear of blaming remote workers for Yahoo’s struggles, but she did suggest that employees who worked remotely were missing out. Her memo about the change explained: “Being a Yahoo isn’t just about your day-to-day job, it is about the interactions and experiences that are only possible in our offices.”

“

Trust your employees to know how best to do their jobs, including where to do them.

—BRIAN CARNEY

History does not record whether any of the affected employees yelped “Yahoo!” in response to the memo, but it’s safe to assume some number of those reactions ended with an exclamation point.

Tale of two companies

For some jobs with certain responsibilities, Mayer wasn’t wrong. But it’s equally certain that for others, forcing them to work where she wanted them to was a mistake.

There are two kinds of companies, according to Jean-Francois Zobrist, the long-serving CEO of the French foundry FAVI: “How” companies, and “Why” companies. The former believe in telling their employees how to do their jobs. They insist on standardized processes and procedures, top-down control, and power and information concentrated at the top. They usually tell their employees where to work too.

To varying degrees, this aptly describes most large corporations today. But there is another sort, what Zobrist calls “Why” companies. They focus on telling their employees why they’re doing what they’re doing and leave the “how” to the individual. FAVI’s factory floor reflected this. Every workstation was customized; machines were often arrayed at what appeared to be incongruous angles relative to each other, and no two places alike, or so it seemed.

In other words, each employee worked in the way that maximized their own productivity, and each was free to experiment to discover what that was. When I and my co-author of Freedom, Inc. visited FAVI while researching our book, we saw custom-fabricated parts racks and tools everywhere we looked.

And each employee could explain why this rack was tilted at this angle, why she made a special rake for gathering parts, and so on. They were creatively engaged in improving their own performance because they’d been given the freedom to do so, and knew they weren’t being measured by anything else.

There were no remote workers on that foundry floor, if only because it’s not easy to cast bronze in your home office. But remote work is best viewed as just one application of that same principle: That employees deserve the trust to organize their work life in the way that makes them most productive.

Do you trust your employees to decide to which group they belong? This is part of an even larger question: Do you trust your employees to decide for themselves how best to do their jobs?

Be a why company

Even from here, in my home office, I can hear the chorus of “Yes, buts…” and “If only it were that simple!” It is simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Our book is a full-length examination of the challenges, pitfalls, and benefits of being a “why” company.

When I say remote working is a scapegoat, I mean it often gets the rap for a load of other problems. If you take away the “how,” for example, the “why” becomes extremely important, even essential. If your employees don’t have a clear mission, combined with a shared vision for what you are trying to accomplish together and how they contribute to that vision, they’ll be at a loss for what to do, or they’ll be doing the wrong things because they’re pursuing different goals.

But the problem, in that case, is not that they’re remote. People are just as good at goofing off, being disengaged and performing makework in an office as they are at home or in a Starbucks. Sometimes they’re even better at it at the office because they’re reacting against being “warehoused” for eight hours a day, or more.

The underlying problem is inadequate communication of the company’s “why,” and that employee’s role in pursuing it. Max De Pree, management philosopher and author of Leadership Is an Art, said it best: Communicate lavishly.

Talk to people about what they’re doing, why they’re doing it. Maybe check in on how they’re doing it, but be careful there. It’s all too easy to slip into that “how” mentality or to be perceived that way. Make sure employees know what they’re supposed to be doing, and why, and don’t just do so once a year in a formal performance review, but do it lavishly and as often as possible.

“

Make sure employees know what they’re supposed to be doing, and why, and don’t just do so once a year in a formal performance review, but do it lavishly and as often as possible.

—BRIAN CARNEY

Be a why worker

It may well be that someone in a particular role needs to spend more time in the office. They have a team that hungers for “interactions and experiences” with them, or they’re missing something important about the group dynamic by being away. But if they understand their job, they’ll come to that conclusion on their own, like as not.

And if they don’t, forcing them into the office won’t help them “get the message.” It will probably just make them resentful and surly, which isn’t a great addition to any workplace.

Fake Work and How to Avoid It

We begin each day with the best of intentions. But we often go to bed at night wondering exactly what we’ve accomplished. The problem? An endless stream of busy work invades our schedule and keeps us from doing the things that really matter. In this episode, you’ll learn the three simple steps for eliminating fake work so you can escape the frustration of meaningless chores and get the results that will drive your business forward.

August 14, 2018

When Goals Don’t Cut It, Focus on Obstacles

Becoming the Right Kind of Person to Succeed

Emily wanted to work in marketing. She was young and had no experience. She’d skipped college and used a portfolio of work and a Praxis apprenticeship to win a spot on the Customer Success team of a growing startup. But her goal was still marketing.

She aimed right at it and started asking people in the marketing department questions how she might join their team. They were busy and it didn’t seem to be working. So she stopped, stepped back, and asked “Who?” instead of “How?” Who would she need to be to get hired in marketing?

It’s not how to get there, it’s who is capable

She’d need to be someone that didn’t cost them time with questions and requests, but someone who saved them time. She’d need to be someone who demonstrated ability in marketing. She’d need to be someone easy to say yes to and hard to deny an opportunity. When she saw the marketing team looking at bringing on an intern, she volunteered to take on marketing intern tasks in addition to her CS role for no extra pay. She made their life easier. She learned some marketing skills. She became the kind of person they wanted. Not long after, she moved into marketing full-time.

Sometimes goals are a distraction. The big shiny end blinds us to the means necessary to get there. It doesn’t just obscure the path, it obscures who we need to become in order to walk it. Emily didn’t need to know how to work in marketing, but who can work in marketing.

Could you handle your goal?

If you imagine a goal, say a certain net worth, it’s not enough to plot a path to it. Such paths rarely work out the way you planned anyway. Instead, ask what kind of person you’d have to be to be capable and worthy of the goal.

A high net worth requires some qualities you probably don’t currently have. If you struggle managing finances now, for example, it will only get worse with more money. Become the kind of person who can handle it. Faithful in little leads to faithful in much. If you have a hard time saying no to people now, imagine dealing with all the askers and hangers-on you’ll have to deal with if you’re wealthy?

If you don’t start working on growing into someone capable of handling the goal, you won’t reach it.

Even vague goals have specific requirements

I tend to keep my end goals vague. But when I have one, I work backward to tease out what obstacles stand between where I am now and that goal, and what kind of person would I have to be to overcome those obstacles.

A few years into my career, I developed a vague goal of entrepreneurship. I knew I wanted to launch a vision, rally the best people around it, and build something that didn’t exist before. That was about as concrete as the goal got. I didn’t know what or how or when. I thought about creating something new and leading a team to execute and asked what would stand in the way of success. What obstacles existed between here and there?

“

Sometimes goals are a distraction. The big shiny end blinds us to the means necessary to get there.

—ISAAC MOREHOUSE

Whatever the venture, I’d need money. Revenue from customers, funds from investors, or both. Getting money for a brand new unproven thing is an obstacle. Surmounting that obstacle required a skill I didn’t have: sales.

Rallying top people around a vision would also require a great network of top people. I had a small one, but it needed to be deeper and wider.

If I wanted to create something worth creating, sell, and recruit, I’d need to be awesome at casting a vision. I’d need to be a great communicator, formally and informally, in writing, speeches, meetings, and interviews. I had some natural talent but would need to seriously level up.

Even though the goal remained vague—create something new someday—the obstacles were clear. I could see who I’d need to become. Until then, even if the opportunity plopped into my lap, I’d be incapable of seizing it and succeeding. I had to become the kind of person for whom those obstacles were easy.

“

Even if the opportunity plopped into my lap, I’d be incapable of seizing it. I had to become the kind of person for whom those obstacles were easy.

—ISAAC MOREHOUSE

The obstacles focus the activity

This led me to leave one great job for a totally different one so I could learn sales. It made me go out of my way to help people and build social capital. It led me to start writing every day, to do as many speaking gigs as I could, mostly unpaid, to do podcasts and videos, to start projects and lead meetings. I didn’t focus on my ill-defined end goal at all. I focused entirely on becoming the kind of person capable of achieving it.

When the right idea struck at the right time, I was ready (or as ready as you can be). I launched Praxis as a complete startup novice on paper. But I had cultivated the attributes and become the kind of person capable of working around or busting through the obstacles that come with launching a company.

Emily didn’t predict her path to a marketing job through CS and intern duties. I didn’t plot the path that led me to build a company. You probably can’t for your goals either. But you can walk backward from the goal through the obstacles along the way and ask what kind of person you’d have to be to overcome them. And you can get to work today becoming that person.

Why After-Action Reviews Are So Important

Military Strategy Could Help Take Your Organization to the Next Level

One of the critical differences between military and civilian organizations is that most military organizations can only simulate their wartime missions in peacetime, and must therefore conduct training which seeks to mimic combat conditions as closely as possible. This is not something that most civilian organizations do with their more high-pressure tasks.

The thinking behind that might be that ongoing operations provide sufficient training opportunities to learn. But if you want members of your organization to learn lessons faster, consider instituting something like the military’s After-Action Review (AAR). I’ll walk you through how that works here.

What is an AAR?

Training Circular 25-20, A Leader’s Guide to After-Action Reviews, defines the AAR as a “professional discussion of an event, focused on performance standards, that enables soldiers to discover for themselves what happened, why it happened, and how to sustain strengths and improve on weaknesses.”

Simulation of combat is resource intensive and demanding, and it is critical that each training event provide the maximum amount of benefits for the costs incurred. In order to ensure this, each major training event incorporates a process of review from beginning to end; the AAR.

Unlike a critique, which may only present a limited number of points of view, an AAR includes feedback from all participants—from the senior leaders to the individual soldiers—whose observations are often just as critical to the success of the unit mission.

Two types of AARs

AARs fall into two general categories, Formal and Informal. The formats are essentially the same, but the determination of whether to conduct a formal or informal AAR is generally based on the level of the unit conducting the training (Company and below tend to be informal, while Battalion and above tend to be formal, although certain squad, crew, platoon and company training events, such as gunnery exercises, may be formally reviewed).

Formal AARs are planned well in advance of the execution of the training event, with extensive preparation. There will be a reproduction of the training area (either on a terrain model, or sand table, a map blow-up or a projection), dedicated observer controllers (OCs) and are conducted where they can be supported most effectively. The formal AAR will also include the data captured in informal AARs conducted by the OCs on site with smaller units. Informal AARs are conducted immediately after a training event by the internal chain of command, at the training site, and require less preparation.

As a Second Lieutenant, I used to conduct platoon AARs with a pocketful of Micro-Armor (miniature vehicles cast in metal) and a hastily sketched out terrain board between our vehicles. I also used to conduct Rehearsal of Concept (ROC) Drills the same way before the event.

As a Second Lieutenant, I used to conduct platoon AARs with a pocketful of Micro-Armor (miniature vehicles cast in metal) and a hastily sketched out terrain board between our vehicles. I also used to conduct Rehearsal of Concept (ROC) Drills the same way before the event.

In fact, the amount of detail that goes into the ROC Drill is usually a good indicator of the amount of detail that will go into the AAR. The AAR for a Brigade Combat Team (BCT) exercise will almost certainly mimic the level of detail of the ROC Drill, especially since the site preparation, training aids and Operations Order (OPORD) will be used in both events.

Key points and formats

All AARs, whether formal or informal, share the same key points. AARs:

Are conducted during or immediately after each event

Focus on intended training objectives

Focus on soldier, leader, and unit performance

Involve all participants in the discussion

Use open-ended questions

Are related to specific standards

Determine strengths and weaknesses

Link performance to subsequent training

The AAR format, regardless of whether it is formal or informal, should include the following:

Introduction and rules

Review of training objectives

Commander’s mission and intent (what was supposed to happen)

Opposing force (OPFOR) commander’s mission and intent (when appropriate)

Relevant doctrine and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)

Summary of recent events (what happened)

Discussion of key issues (why it happened and how to improve)

Discussion of optional issues

Discussion of force protection issues (discussed throughout)

Closing comments (summary)

“

An AAR includes feedback from all participants—from the senior leaders to the individual soldiers—whose observations are often just as critical to the success of the unit mission.

—MIKE HARRIS

Planning and execution

The AAR is part of every training event. There are four phases, which are run as the training event is planned and executed.

Phase 1: Planning

During this phase, the trainers select and train qualified OCs review the doctrinal inputs to the training event and begin identifying the data to be captured, schedule the AARs, identify participants, select the sites, select training aids and review the planning for the AAR.

Phase 2: Preparation

The trainers will review the Operations Order (OPORD), Mission Essential Task Lists (METL) and doctrinal guidance and extract the training objectives and determine which key events OCs are to observe. Once the training event begins, the OCs will record their observations and these will be collected and organized in order to reinforce teaching points. They will also recon the AAR site and begin site prep and rehearsals.

Phase 3: Execution

Following the format, the trainers will conduct the AAR. Goals are to seek maximum participation from members of the training unit, focus on training objectives and teaching points and to record key points derived from the observations of all participants.

Phase 4: Follow up

As the training unit recovers from the exercise, the chain of command will incorporate the AAR findings into identifying and correcting weaknesses through retraining and revising Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). These changes in training will be incorporated into the Yearly Training Plan (YTP) and Yearly Training Calendar (YTC). The AAR will also be used to refine the commander’s readiness assessments in the Unit Status Report (USR).

Safety, on!

Safety cannot be overemphasized in training exercises. Simulations of combat carry risks to participants, and the more realistic the simulation, the greater the risks. Pyrotechnics used to simulate artillery can cause injuries, vehicular accidents will occur, even something as simple as food storage can have catastrophic consequences if not properly executed. During an exercise at Fort Irwin, one of the units that we were working with suffered two fatalities when a HMMWV overturned in a ditch while speeding.

Never underestimate the impact of Murphy’s Law. Safety and force protection should be specifically addressed in every phase of the AAR, just as they are incorporated into the training events. As my first squadron commander used to say before each event, “There is nothing that we will do here today that is worth your life.”

How to AAR

In a military environment, an AAR provides critical data to a unit commander, who will then incorporate that data into improving unit performance and, ultimately, securing victory on the battlefield. There are aspects of the AAR that civilian enterprises are finding useful, and I strongly recommend that those managers and other leaders who seek to incorporate AARs into their operations review Training Circular 25-20.