Richard Goodman's Blog, page 19

June 5, 2022

I watched a movie

The other day I watched an old film, The Train. It was released in 1964, shot in black and white, and stars Burt Lancaster and Paul Scofield. The film takes place in France toward the end of World War II. It centers around the effort of a German colonel, played by Scofield, to transport hundreds of French paintings, by great artists like Picasso, Renoir, Gaugin and Matisse, to Germany to be sold for the war effort. Lancaster plays a French train station director who is also a resistance fighter and who tries to stop the train from reaching Germany.

One of the central questions of the movie is: are paintings—and, by inference, art in general—worth dying for? As the train makes its way to the German frontier, resistance fighters sabotage it by blowing up the rails, only to have those rails repaired and the train continue on its way. When the partisans are caught, they’re shot, and in a final scene, twenty or so hostages are shot when the train is derailed for good by Lancaster.

Of course, the film’s question doesn’t solely rest on art itself. The paintings are worth lots of money, and so in this context the resistance fighters are dying to hinder the German war machine.

Still. It’s a rather daring idea for a war film. Blowing up a bridge, sure, an audience can see partisans risking their lives for that. But for a Matisse?

I sometimes consider weighty questions like this when I go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Or any museum, really, but this is the one I’m most familiar with. Here you have this vast stone building located on some of New York City’s most spectacular real estate at the edge of Central Park, devoted, to a great extent, to flat, two-dimensional pieces of canvas covered with paint. Room after room, filled with them. Paintings. Just paintings. They don’t do anything. They just are.

No one seems to think that’s a bizarre idea. To devote a train-station-sized building to room after room of paintings.

I certainly don’t. Because this is humankind at its best. This is what we can create at the full measure of our powers. Beauty.

When I go to the Met, I explore its many treasures, and, as anyone who has been there knows, the Museum’s collection of art, of all kinds, seems endless. But I always end up standing before one paining, Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja. The portrait was painted in Rome. It is of Velázquez’s enslaved servant who accompanied Velázquez to Italy.

Juan de Pareja by Velázquez

Juan de Pareja by VelázquezVelázquez’s painting was part of a big exhibition at the Pantheon. One commentator wrote that the painting "was generally applauded by all the painters from different countries, who said that the other pictures in the show were art but this one alone was truth."

The New York Times film critic at the time wrote about The Train that the viewer is “not likely to be held in great suspense by the peril of a lot of paintings.”

I was, though.

May 31, 2022

Cataracts!

I’m going to have a cataract operation today. I’ve been having problems with driving at night. And seeing distances. So, a month or so ago, I went and had a thorough eye exam. They said I had cataracts.

“Everyone gets them,” the doctor told me. I wonder how many times he says that in a day.

I set up two dates to have the operations. One eye first, and then, two weeks later, the other.

I made the mistake of trying to make a joke while I was discussing the details of the process with the doctor’s assistant.

“Now, the doctor will operate on your left eye first,” she said.

“Is my left eye from my point of view or from your point of view?”

“What?”

“Well, if you’re looking at me, my left eye would be different than from my point of view.”

“It’s your left eye,” she said.

“Yes, but my left eye would be different if you’re looking at me versus…”

This went on for a few minutes until we reached a standstill. Then I dropped it. I hope I have this right.

The assistant gave me a pamphlet listing all the things I needed to do to prepare for the operation. I had to dispense two kinds of eyedrops four times a day starting three days before the procedure. (“Procedure.” Sounds like a word you’d apply to a lobotomy.)

Check these out. And I quote:

“Shower and wash your hair the night before surgery.” (Have they been confronted with repulsive grooming in the past?)

“Do not bring valuables.” (Is there a cataract-based ring of thieves that roam the clinic?)

“Do not wear make-up face creams or any other scented toiletries.” (I guess the surgeon doesn’t want to gag. Or worse, sneeze.)

“Wear loose fitting, comfortable clothing.” (A caftan?)

Then this in bold face:

“6 HOURS PRIOR TO SURGERY—Light meal or snack. Clear liquids—apple or cranberry juice.” (Since when is cranberry juice clear?)

“Black coffee or tea. NO cream or milk. NO dairy.” (I’m wondering how half-and-half affects the eyes.)

Finally,

YOU CANNOT DRIVE HOME! (I have to stay there forever?)

Let’s do this thing.

May 28, 2022

Veselka

I lived on Tenth Street, in the East Village, in the mid-1970s,. It was a wonderful place to be. I had little money but everything I wanted. I had the rollicking 2nd Avenue Deli with its crowded interior, its alluring smells of pastrami and corned beef, and its weary waiters. I had the Polish Meat Market, on Second, between Ninth and Tenth Streets. Visiting there was like visiting Cracow, only faster. I had the small, aromatic cheese shop on Eleventh Street near First Avenue where they made their own mozzarella, round, unblemished, pure white. I had the Jewish bakery on Ninth Street, between Second and First, with the ancient owners who moved with great deliberation from loaf to loaf searching out what you desired.

And I had the Veselka Ukrainian Coffee Shop.

It was small, situated on the corner of Ninth Street and Second Avenue. The food was cheap and good. In the winter, when the ice made me slip, and the wind blew me sideways, there was no better place to go to restore the soul and stomach. And it was always within my budget.

Veselka, about the time I used to go there.

Veselka, about the time I used to go there. The waitresses hardly spoke any English. It’s an enlightening experience to walk into a restaurant in your own city where people do not speak your language. It made me fumble trying to communicate, and it was humbling, but it was exciting as well. It felt like entering another country, and, in a real sense, it was. This is what New York offered often, especially where I lived, in the East Village, and I found it every time I went to Veselka. While I didn’t need a passport, it felt like carrying one with me wouldn’t be inappropriate. Veselka was that kind of place.

I was young and naive, and I didn’t know where Ukraine was, or even what it was. All I knew was that the food at Veselka was good and cheap and filling and my money stretched very far there and I loved sitting inside sheltered from the harsh winter day. It was a homey place back then, as if you’d stepped into a Ukrainian grandmother’s kitchen. The hot barley soup, generously thick and substantial, was served with pumpernickel bread with little hills of butter, that, spread unevenly across the bread and dipped into the soup, would transport me. I walked out of Veselka, belly full and content, ready for whatever the relentless New York City winter threw at me.

Veselka, and places like it in my neighborhood, were a young man’s dream. I was constantly being educated in New York, the world’s ultimate continuing education, and often it was through the food I ate, with smells and tastes I’d never encountered before. Every day it was possible to get advanced degree in a foreign culture by stepping into a store or restaurant like Veselka staffed by people from a place you’d never been to before.

I have been to Veselka several times since I left that neighborhood many years ago. It’s grown and gotten a bit fancy. They even have tables outside and non-Ukrainian servers who speak idiomatic English and are probably aspiring actors or musicians. I grumble about the lost Veselka, the real Veselka, sounding like an “in-my-day bore” I swore I’d never become.

Veselka today

Veselka todayBut ultimately, the most important thing is that it’s still there, Veselka. Long may it thrive, and the country that inspired it.

May 20, 2022

Confronting the repo man

Debit and credit. I want them balanced, or as nearly as I can make them. As I get older, though, the debit column gets more substantial. At 76, I begin to lose more things than I gain. I find I’m being asked to relinquish aspects of myself. I begin to realize that they’ve been on loan. Things like dexterity. Balance. Reaction time. Good vision. And, of course, memory. The loan officer comes to repossess them. He comes brandishing a list of physical and mental powers that now, officially, belong to him. They always did, of course, but I was under the mistaken illusion they were mine. They never were. I try to protest, but he simply goes about his business of taking things back. “Just following orders,” he says. “Nothing personal.” It is, though.

I look at the debit column, and it’s worrying. It’s getting longer. I’m doing anything and everything to add to the credit column. I want knowledge and experience coming in, not just flowing out.

As the white-bearded bent-over old man in the Goya etching declares, “Aun aprendo.”

“I still learn.”

I went to a writer’s conference once where Molly Peacock was part of a panel. The subject was writing outside of your genre. Molly, a poet, was talking about writing prose. “It made me anxious,” she said, “but fear makes you feel young.”

So I’m going to live with the woman I love in a place I never would have chosen to live in my wildest dreams—southern Louisiana. I’m anxious. But, like the good Molly Peacock said, that worry is making me feel alive. That’s the point, isn’t it? When the debt collector comes to repossess the things I took for granted when I was young—and he will come—I have something to add to the credit column. Whether it makes me anxious or not. I want to feel alive.

May 14, 2022

Formula

The current alarming shortage of baby formula has put me in a time machine. It’s caused me think about my daughter when she was a baby many years ago and when her mother and I fed her formula. I hadn’t thought about that in years.

Giving a baby a bottle of formula is a simple, ordinary act. The baby is hungry, and you know it because she leaves little room for doubt, and so you prepare a bottle and give it to her. She drains it, with great concentration, and then she’s happy. Or at least not unhappy.

I loved to give my daughter her bottle. I cradled her in my arms, steadying the tilted bottle while she emptied it like she was in a drinking contest. I was giving her something she needed. I was the provider. It’s one of the most elemental of human satisfactions.

So those mothers and fathers who cannot provide their child with formula, through no fault of their own, are worried about feeding their babies, of course. But I’m sure something else must be there, and that is the basic idea of not being able to provide. That must be so dispiriting.

I was a stay-at-home dad for the most part. We had some help, so I don’t want to paint a picture of me taking care of her all day, every day. But I often did the shopping, and that included buying her formula. I became an expert. This is one ability I’ve lost, just like the ability to determine a child’s age precisely in months simply by looking at it. All mothers can do this. After I spent a lot of time in the playground, I could, too.

With formula, it was all about prices. I would buy my daughter’s formula at the grocery store, but not exclusively. Formula is sold in pharmacies as well and in discount stores and other places. (We didn’t have a Walmart or Costco back then in New York where we lived.) I kept my eye wide open for sales and price differences. I knew, to the penny, how much formula cost, at every location I went to that sold it. Mothers are frugal because, of course, they have a budget, and especially so when they buy something regularly and frequently. A twenty or thirty cent difference per can is important, and noted. And I did.

There where times when I was pushing my child in her stroller in a store, and I would see a mother about to put a case of formula in her cart, and I would say,

“You know, that’s $24.65 at Duane Reade.”

“Really?”

“Yes. And $25.20 at D’Agostino’s. It’s on sale this week.”

“Oh?”

“That’s a $5.23 savings per case.”

Mothers never looked twice at me. They knew I knew what I was talking about, and they were always looking for a deal. We all were. I dipped my foot into the economy of mothers, and it taught me what skilled economists they are and how much they balance in their heads. Has anyone calculated how much mothers save their families in a lifetime by being vigilant and resourceful? I bet the number is staggering.

I loved taking a can of the formula out of the packaging, shaking it, pouring it into the bottle, and warming it up for my daughter. When she got to the point where she could hold the bottle on her own, that was another of the many milestones as a parent that are both satisfying and a little melancholy. Things you’ll never do, or see, again. This whole formula shortage has reminded me of giving bottles to my daughter and how that time of her life happened only once, and how she moved on from there to the inevitable and proper role of not needing you and saying, as she did so many times, “I want to do it myself.”

May 8, 2022

Wish you were here

"Mothers are all slightly insane," Holden Caulfield says at one point in The Catcher in the Rye. I always knew what he meant. It was never a quote that I puzzled over. In five words, he nailed it.

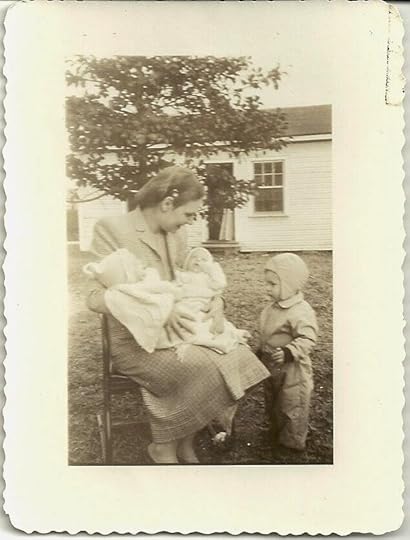

My mother holding me, age 7 weeks

My mother holding me, age 7 weeksYes, mothers are all slightly insane, some more slightly than others. They're insane because they can never be certain, ever, that their child(ren) is(are) completely without harm. They are on some kind of alert twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year, always. Some part of them never sleeps. You can't be that attentive and worried for that long and not be slightly crazy. Combine this worry with powerlessness—as soon as the boy or girl steps out of the house (out of the room, actually), they can't do a thing to protect them.

Holding her twins with me pondering. She had three children within eleven months.

Holding her twins with me pondering. She had three children within eleven months.I think of my own mother, of her difficult life, and of her living alone after her divorce. For years. I think of all that she tried to do with that ache and pull toward her children. I think of her carrying that ache of loving me and that love unrequited, and how can you stand that day after day year after year? She used to say to me, "I get lonely for you, Richie." I think of her probably feeling she hadn't been a good mother, and how that must have devastated her after worrying about us so deeply and so continuously. I think of her bright, sharp mind, love of writing and reading and of her unblemished soul. I think she did the best she could.

In Old Greenwich, CT, sometime in the 1970s.

In Old Greenwich, CT, sometime in the 1970s.It's too late to tell her that I love her. I tried to do justice to her memory in a piece called "The Wheaton Girl.” She went to Wheaton College. "The happiest days of my life," she told me. I doubt she'd like it, even though I wrote of of her intelligence and of her kindness. She didn't want her weaknesses exposed, and who would? I wrote another about watching her hang out the wash when I was a kid. Still not right. I'm not here to say anything silly like, tell your mom you love her before it's too late. (Or maybe I am.) I'm just here to say to you, Mom, you deserved better. But I can't. Because you're dead. I think about you every day. I wish your life had been easier. I hope you've found peace.

The only time my mother saw my daughter, Becky.

The only time my mother saw my daughter, Becky.

May 7, 2022

A day in the life of Marie-Claire Blais

Sometime in the mid-1970s, I read Edmund Wilson’s O Canada, An American’s Notes on Canadian Culture. As far as I know, it’s one of the few—if not only—books on Canadian writers written by a major American author.

In his book, I read about writers I’d never heard of before and that probably many Americans do not know to this day. One of them was Marie-Claire Blais. Wilson writes rhapsodically about Blais, who wrote in French. He says she is “in a class by herself” and “may possibly be a genius.” Because of his enthusiasm for Blais, I read the translation of her book, A Season in the Life of Emmanuel. It was published in 1965 and has an introduction by Wilson, who, it turns out, eventually met and befriended her.

I had never read anything like it. It has startling writing about poverty and repression in rural, Catholic Canada. I have since lost the book, but I remember clearly a line about “the smell of the grandmother.”

Years later, when I was living in New York City, I saw that Marie-Claire Blais was going to speak at the New York Public Library. I went. I remember it was at the Mid-Manhattan branch. Why they hadn’t booked her into the main branch, I do not know. They should have.

I went up to her afterwards and told her how much I loved A Season in the Life of Emmanuel, about how much the book meant to me. I told her she was brave to write about these things.

“You have to,” she said. Then, out of the blue, she asked me if I’d like to spend the rest of the day with her, walking about the city. Of course, I said yes. We went down to Astor Place in the East Village, and walked around, eventually ending up at a Barnes & Noble bookstore that was located there. Like the Mid-Manhattan Library, it no longer exists. Blais spoke English, but not as fluently as I expected from what Wilson had written about her. I learned that she lived half the year in Key West.

Marie-Claire Blais at about the time I met her

Marie-Claire Blais at about the time I met herDuring that afternoon in the bookstore, she spotted two writers she knew and spoke to them briefly. She was easy to be with, but I can’t say that I grew to know much about her or that we became friends. But it was one of those encounters you treasure in your memory, especially if, like me, you’re a writer and have had the luck to encounter one of the writers you admire in the flesh and had the opportunity to tell them how much you love their work. I felt as if I’d been given a sign. That I belonged in that world.

She died last November. She never received her proper recognition, I don’t think, and so I was glad to see a long-overdue New Yorker piece in 2019 about her, “Will American Readers Ever Catch on to Marie-Claire Blais?” Let’s hope they do.

April 30, 2022

The man in the mirror

One day, things begin to change. You don’t remember exactly when, but they do.

You start getting out of bed a little slower, a little more reluctantly. You find yourself moving toward the bathroom a bit unsteadily, and your back is creaking like an old floor. You look at yourself in the mirror and you see a stranger. Who the hell is that frightening-looking man? How did he get in the house? He’s old.

Suddenly you have skin hanging under your chin like a suspension bridge. Hair grows out of your nose and ears like wheat, and your eyebrows start looking like Bertrand Russell’s. Let’s not forget the encroaching gauntness that slowly but surely makes you look like you’ve just been liberated from Bataan. And stairs missed, names forgotten, routines ferociously protected, and the more frequent trips to the pharmacy.

Getting old.

Getting old, and with it, so many new ways the world looks at me, and I at the world.

Inside, I’m young and eager and robust. But the face I show to the world doesn’t mirror this energetic youth I am inside.

Faustian thoughts begin to crowd my mind.

Living where I do, in New Orleans, where there is a constant ebb and flow of youth, makes me think dark thoughts indeed. I start to have covetous rants in my mind, the kind you hear old men make to themselves under their breath in scary movies.

Why should they be young, I think, and I be growing old? Why should they have their life ahead of them, and I have mine mostly behind me? I—I who would know how to use their youth to its fullest degree—I should have their youth!!!!

I want your youth, I think, you there, bright savage boy, with your studied insouciance, flip-flops, tousled hair, tattoos with Chinese characters, and torn T-shirt. I covet what you have, and I’m going to have it. In the dark of the night I’ll come to your room and threading my way among beer cans, empty ramen containers, assorted balls, X-box, bong, condoms, bottles of booze, female clothing left behind, I’ll come to you while you’re sleeping. Then I’ll sink my teeth into your neck, and I’ll suck your blood. I’ll imbibe your youth, drain it from your body. I’ll feel its strength shoot through my own veins, replenishing me!

Then I’ll leave you there, with two tiny denture marks on your neck.

Paris in bad weather

The last time I was in Paris, it rained. When it didn’t rain, it threatened to. This was in October, so leaves were starting to fall from trees, and that added a sense of forlornness to my visit. Each morning, I stepped out from my hotel on the Left Bank just off the Boulevard St. Germain into a dull gray morning. The sky hung low, the color of graphite, and it seemed just as heavy. The air was cool and dense. But I wasn’t disappointed. After a shot of bitter espresso, I was eager to go.

That week in October I set myself the goal of following the Seine, walking from one end of Paris to the other. I had bad weather as my companion, and a good one it was, too. I walked along the quays and over the bridges in a soft drizzle. The colossal bronze figures that hang off the side of the Pont Mirabeau were wet and streaming. The Eiffel Tower lost its summit in the fog. The cars and autobuses made hissing noises as they flowed by on wet pavement. The Seine was flecked with pellets of rain. The dark, varnished houseboats, so long a fixture on the river, had their lights shining invitingly out of pilothouses. None of this I would have seen in the sunlight.

Then there is the matter of food.

There may be no Parisian experience as gratifying as walking out of the rain or cold into a welcoming, warm bistro. There is the taking off of the heavy wet coat and hat and then the sitting down to one of the meals the French seemed to have created expressly for days such as this: pot-au-feu or cassoulet or choucroute.

I remember one rainy day on this trip. I walked in out of the wet, sat down and ordered the house specialty, pot-au-feu. For those unfamiliar with this triumph, do not seek enlightenment in the dictionary. It will tell you that pot-au-feu is “a dish of boiled meat and vegetables, the broth of which is usually served separately.” This sounds like British cooking, not French, and the dictionary should be sued for libel. My spirits rose as the large smoking bowl was brought to my table along with bread and wine. I let the broth rise up to my face, the concentrated beauty of France. I took that first large spoonful into my mouth. The savory meat and vegetables and intense broth traveled directly to my belly. I was restored.

I sat and ate in the bistro and watched the people hurry by outside bent against the weather. I heard the tat, tat, tat of the rain as it beat against the bistro glass. The trees on the street were skeletal and looked defenseless. I looked around inside and saw others like myself being braced by a meal such as mine and by the warmth of the room. The sounds of conversation and of crockery softly rattling filled the air. Efficient waiters flowed by, distinguished men with long white aprons, working elegantly. Every so often the front door would open, and a new refugee would enter, shuddering, with umbrella and dripping coat, a dramatic reminder that outside was no cinema.

I finished my meal slowly. I had left almost all vestiges of the wet cold behind. My waiter took the plates away. Then he brought me a small, potent espresso. I lingered over it, savoring each drop. I looked outside. It would be good to stay here a bit longer. It was so comforting.

But I got up to go. Paris—gloomy, rainy, starkly beautiful Paris—was waiting.

April 23, 2022

Death of a Tree

We had a tree cut down Saturday. It was a water oak, around 70 feet tall. The problem was that it was too close to the house, and this is Louisiana where we have hurricanes regularly, and with hurricanes come high winds, sometimes above 100 mph, and with those winds come trees toppling onto houses. It happens all too frequently.

Our water oak was fully grown, meaning that it was on its decline. At roughly 70 feet, growing two feet a year, it was somewhere around 40 years old. Water oaks live just 50 years. So, that when those strong winds inevitably arrive, our water oak, aged and somewhat shaky, more and more would likely be blown over. Of course, it might fall the opposite direction of the house. Then again, it might not. Though my partner and I love trees, we only have one house, and we want to keep it. So we made the decision to have the water oak cut down.

We hired an outfit to do that. They arrived promptly at 7am on Saturday and went to work. They set their large chainsaws to the base of oak and began. You know the sound, satisfying and lethal. Soon enough, they had nearly sawn through. They had a small tractor with them and drove it against the now-precarious trunk. That did it. There was the slow-motion toppling, and the heavy sigh of the tree hitting the earth, like an elephant falling to the ground. A tree newly fallen. The starkness of that.

Then, a surprise.

The force of the tree falling 70 feet smashing against the earth with force split open one of its big branches, creating a large blonde mouth. In it was revealed a teeming beehive. We had no idea. The bees careened around their exposed hive like electrons, in a fury. The crew debated what to do. They couldn’t chainsaw the fallen tree into sections to be hauled away because of the bees. No one wanted to be stung. And let’s face it, the bees had every reason to sting anyone who came near.

So they burned the beehive and killed most of the bees. No! my partner and I said to each other. We know the importance of bees, what good they do, and, lately, of their sudden deaths and scarcity. It especially tore at my partner, who has been living in this house much longer than I have and whose love of animals of all kinds is strongly-felt. But destroy the hive they did, and we could only live with that.

They brought back their chainsaws, and they sawed the downed tree into sections and hauled them away. They left just a massive stump, bright-surfaced and obvious. The remnant of a colossal amputation.

In a matter of hours, forty years, gone.

The next morning we looked out onto the yard where before had been a 70’ tree with sprawling branches and a canopy, a reliable and comforting sight. The absence of a tree is profound. I asked my partner what she would miss the most about the tree, and she said that it would be the swaying of the branches in the wind.

It was a complex thing, this water oak, having become what it was in its height and sprawl. It had a presence. Now that it was gone, the air was empty before us. Privacy and shade were gone. Movement, moods, lyricism were gone. This tall stationary thing had a grace, its branches bending and arching when the wind moved against and through it. The tree’s arms, with the winds urging, created a choreography, every time original, and it never ceased to delight and impress us. As did the sounds it made, the swooshes of branches. In a high wind, the branches weaving and crashing against one other made you call one another to come and see.

All that, and the distinct way the branches sprawled and grew, and the tree’s many moods, and its unique way of being alive, gone. Now where it was, nothing, just air.

What I feel? Gratitude.