Richard Goodman's Blog, page 17

October 12, 2022

Darkness invisible

When someone says they're “depressed,” they can be referring to a one-day dispiritedness. Or even something lighter: “I'm depressed the Giants lost.” Or: “It's depressing it's raining.”

Or, more seriously: “He's depressed his wife left him.”

But at its worst, at its most profound, depression is crushing. A weight that can only barely be borne. I think “depression” should have one meaning, and one meaning only, like death. There is no “death lite” or “almost death.” “Depression” should be reserved for that one black night that never turns into day. I think it's because of the enormous range of meaning of the word that some non-sufferers don't see chronic depression as that dire. (“You're depressed? You'll get over it.”) It is dire. This dismissiveness is what often makes depressed people ashamed to speak of it. Once again, that great, oily manipulator—shame.

People have tried through the years to describe what it's like to be profoundly depressed. Most famously, William Styron in Darkness Visible. It's a small book full of despair, and he writes truthfully when he says, “the pain of severe depression is quite unimaginable to those who have not suffered it, and it kills in many instances because its anguish can no longer be borne.” Styron also writes about the word “depression” being unsatisfactory for what the malady brings to the soul.

But as with all fine writing, there is a kind of paradox to it. Styron's writing is so fluid, so able, so lucid that, somewhere, I'm thinking: this is too beautiful, too lyrical, to represent that utter bleakness that is depression.

I think if I were to try to capture what it's like to be profoundly depressed—and I declare that I cannot—I might write about it monosyllabically, or as close to that as I could get.

Weight. Dark. Hopeless. Tears. Gone.

I was profoundly depressed in my forties. My willpower vanished. All sense of gratifying routine was gone. Responsibility meant nothing. Everything in myself I relied on deserted me. Nothing could penetrate this darkness. It was an emotional black hole where all light was sucked into itself. Movement was impossible. Suicide seemed reasonable. Even desirable.

You have to think: for someone who loves life so much, what could turn them so against it?

Something you don't stand a chance against.

Use the word judiciously. But if you are depressed, profoundly depressed, speak it. Let yourself be heard. And if someone tells you they're deeply depressed, listen to them. For me, at least, it was only through the help of others, and of one woman in particular I confided in, that I emerged, finally, into daylight. For a good while, at least.

But, like the ocean, I respect depression's might and ability to drown.

October 4, 2022

The personal trainer

My girlfriend gave me an hour session with a personal trainer as a birthday present. I had been whining about not being in shape. This was very nice of her, and it was also a handy way of shutting me up.

Actually, I was looking forward to it. At my age, which is 77, I need to do anything and everything I can to detour the rapid degradation of my body. Note to people my age or thereabouts: staying away from a mirror is extremely helpful.

So, a few days ago, I arrived at the gym, ready and willing. The trainer introduced himself. His name is Brian. He is huge. Like some sort of redwood. Even the loose track suit he was wearing looked tight. If you put him on a pedestal, you’d think, who did that statue? I’m running out of comparisons.

Clipboard in hand, he sat me down and began asking me a series of questions. He’s an affable guy. As he listened to me, he jotted down little notes. Even his hands seemed muscular.

“What are your goals?” he asked.

“Well,” I said, thoughtfully, “I’m not sure what’s a realistic goal at my age. Bench pressing 600 lbs is probably not within the realm of possibility.” Or is it?

“Probably not,” he said, an appealing smile appearing on his face. “Ok, let’s have you run through a few drills to see what sort of shape you’re in.”

He had me get on the treadmill first. He started the machine off at a slow walk.

“This ok?” he asked.

I think the setting was “Grandad.”

“Yes, good.”

I can do this. I can walk.

Note: this is not me.

Note: this is not me.He adjusted it several times to make it go faster. Then I started feeling like: where am I going? What is the meaning of life? Something about walking and going nowhere brings out the nihilist in you.

“Ok, good,” he said, noting something on his clipboard. What was it he wrote? “Alive,” perhaps.

He had me a do series of exercises. Curls with hand weights, push-ups against a bar, stepping up and down on a block of wood, etc. Then several sets using those menacing-looking gym machines that look like they had a supporting role in 50 Shades of Grey.

Pain? Pleasure?

Pain? Pleasure?When I completed an exercise, Brian said, “Good job!” Even if the exercise was fairly easy, he said it. It’s surprising how positively I responded to this reinforcing praise, even for doing something one step harder than tying my shoe. I nearly responded, “Gee, thanks, Dad!”

In fact, this made me realize that almost every male authority figure—teachers, coaches, bartenders, bus drivers, etc.—has been a father figure to me from whom I sought approval. Which explains a lot. And which makes me wonder if I’ve ever had a simple encounter with any male I’ve ever met in my life. Has it always been about seeking my father’s approval? Which makes me….what a minute! I’m just here for a workout, not for analysis. Let’s get back to the machines.

Along the way I asked Brian about himself. Turns out that he got one of his degrees at the University of New Orleans where I taught English for ten years.

“I actually grew up in New Orleans,” he said. “In Gentilly.”

That’s a neighborhood not too far from the university. I always thought it was such a pretty name, Gentilly. It’s also the name of a particularly delicious cake, a piece of which I could have eaten then contentedly instead of exercising. Followed by a sugar coma.

This…or exercise? Thoughts?

This…or exercise? Thoughts?But, no. Brian kept pushing me. That was his job, after all. That was the reason I was there. Because I was too damn lazy to work out by myself. And even if I did have the gumption, I wouldn’t know what to do. Unsupervised, I’d probably design a workout for myself that I could do while watching TV. So, deep down, I was glad to be in Brian’s hands. Clearly, he knew what he was doing. Clearly, he had a plan. There is something so gratifying about putting yourself in the hands of someone who’s capable.

He kept pushing me and writing notes down on the clipboard.

I began to get tired. How much longer is this workout? I thought at one point. I didn’t say that out loud, mind you. I didn’t want to be put in the “Wimp” section of Brian’s report. The thing about a trainer is that he knows you want to quit. But he won’t let you, despite whatever woebegone, melodramatic look you assume, however hard and pitifully you pant. And, believe me, I did—all of that. At one point, I was grunting like a feral pig. He ignored me.

This didn’t work with Brian.

This didn’t work with Brian.A few more exercises, and then, finally, it was over. I was spent. My chest was heaving. I was sweating. But I felt good. I’d lasted.

“Good job! You did really well,” Brian said, reaching down from his height and shaking my hand.

I really think he meant it. It sounded like he did.

I thanked him, and we made an arrangement for me to come for a second session that following week. I walked out of the gym feeling wrung out but slightly heroic. That’s the thing about a real workout, isn’t it? You make yourself, in a very small way, and for a very short time, a hero.

When I got home, I began the conversation with my girlfriend,

“My personal trainer said….”

September 26, 2022

43 bis villa d'Alésia

The year is 1972. We’re young, Alex Jones and I. In our mid-twenties. We have decided to travel through Europe for as long as our money will last. We’ve quit our jobs and emptied our meager bank accounts. We have no responsibilities. We have enough money to travel for a year, at least. We have our shiny unbroken backpacks. We meet up in Greece and travel through Eastern Europe that summer, storing up adventures and encounters.

Sometime that summer, as we are tramping along, Alex says, “We need to live in Paris.”

I’ve never been to Paris, so, I think, why not?

When we arrive, we go to the American Center where they have listings of apartments for rent by Americans for Americans. We find one listing for an apartment in the 14th arrondissement, wherever and whatever that is. The address is 43 bis villa d’Alésia. The short description sounds promising. I go there alone. The apartment is located on a pretty little curved street that is cobblestoned.

I knock on the door, and it’s answered by Dorianne Lee, a young American woman from Hawaii who teaches English in Paris. She leads me up a flight of stairs to show me the apartment. I encounter a huge room. It has door-high windows that open to the street below. I almost gasp. I’ve never seen a place like this.

“I’m looking,” Dorianne says, noting me carefully, “for a female roommate.”

I realize this an opportunity that must be seized. Oh, no, you aren’t, I think. You’re looking for two guys. And those two guys are us.

I return with Alex. He’s from Tennessee, and he can charm a spoon with his beguiling southern speak. So, after one or two hours of flattery, promises and little white lies, not to mention traveler’s checks, we convince Dorianne to accept us as roommates. I wonder, now, who was looking out for us? Someone, somewhere, I’m certain.

43 bis villa d’Alésia. At the top of the stairs, a door opened into the kitchen, which was spacious, friendly. Then, to the left, a doorway that led to the main room. It was a huge, light-filled room. It had been a painter’s studio. Think of it: we were living in a painter’s studio in Paris! That was out of a book. Or out of a dream I was too inexperienced to have.

The vast room’s ceiling was two floors in height. The wall that faced the street was made entirely of glass, floor to ceiling. The glass was opaque. You couldn’t see through it, but a profusion of natural light entered the room. In the center of this glass wall were those two large doors, also of glass, that opened to the street. We threw them open in good weather, inviting all of Paris into our room. Sounds, smells, conversations, footsteps on the cobblestones below, the songs of birds, all became part of our every day. Not to mention the Parisian air, traced with diesel fuel and life.

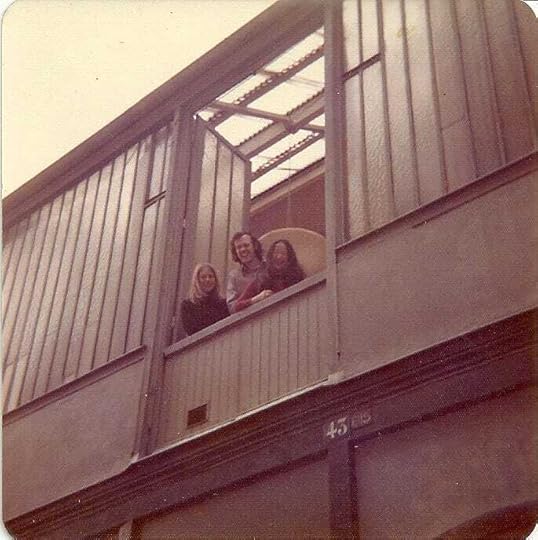

Looking up at our apartment at 43 bis. Alex (center) and Do (right)

Looking up at our apartment at 43 bis. Alex (center) and Do (right)Upstairs was Dorianne’s room and, beyond that, a second bedroom. From Do’s—everyone called her Do—room, there was a balcony from which you could look out onto the large main room below. This often became a stage where one of us, usually me, created manic, improvised, often interminable theater after dinner for everyone below. There was a round table in the atelier where we ate and talked and laughed and told stories and where guests sat when they came to eat Do’s wonderful food. Because Do was a wonderful cook.

The author at the entrance to 43 bis

The author at the entrance to 43 bisThere were times when I’m sure Do might have regretted her decision to let these two rogues into her life, much less into her apartment. She was gracious and calm. We were coarse and boisterous. In the morning, on her way to work, she would inevitably encounter a half dozen empty wine bottles on the table and ashtrays heaped to overflowing with Gitanes and Gauloises, those harsh-tasting French cigarettes. She might have said no to us and saved herself from several near nervous breakdowns. But, years later, she’s still talking to us.

I speak no French. But I'm bold, and I don't mind making a fool of myself. I will learn, bit by bit. I’ll enroll in a class at the Alliance Française. The French I will blurt out will sound like baby talk. I won’t care.

In our neighborhood, there is a store with the word boucherie above the entrance. I can see, looking at the display of meats in the window, that it's a butcher shop. There's one with the name boulangerie written on it window. Bread, I see. A bakery. The bread is long and tall. How can you make sandwiches of that? The store is full of women buying. Later, a Tunisian bakery in the Latin Quarter will provide the answer to a hungry me on how a sandwich, cheap, filling and delicious, can be made from a baguette.

Everything is new to me, and different, and has the ring of a place that is very confident of itself. I see different cars. Renault, Peugeot. What are these? I see workers in blue jump suits. Blue?

My ignorance is bliss. Indeed, because it puts me in a state of wonder and of learning. It throws me back in time to when I learned things for the first time as a boy. What is more exciting than learning? In another sense I am being uneducated. I am seeing that how we live in the United States is not the only way to live and in fact, in many cases, clearly not the most satisfying way. How narrowly I looked at the world before. Every step I take is a lesson. A tutorial. There is no tuition.

I walk down the rue des Plantes and come to rue d'Alésia. It is only many years later that I learn that Alésia was where a great battle took place between the Romans and the Gauls. I turn right, and I remember that this is the way to the subway. Which they call Métro. Our stop is Alésia. There is a restaurant next to the entrance and a large stone church you can see when you turn the corner. I don't really know where I am at the start. But one thing I do know. This is our neighborhood in Paris.

Alex and I settle in. We have six months ahead of us where we have Paris all to ourselves. Every day, we’ll wake up in Paris. Every day, we will set out to discover this storied city.

Now, fifty years later, I look back at those two young men, and I try to speak to them. I reach out to them. Don’t take this for granted. I want to tell them how lucky they are. Did they know? I hope so. I think so.

September 19, 2022

Pamela on a Saturday

New York City. Years ago. A sharp fall Saturday. The air smelled cool and delicious. It was invigorating, like a shot of pure oxygen. I was walking alone up Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village when I saw her. She was standing on the corner of Eleventh Street about a block away. I could see her curly red hair in all its wild abundance, a crimson beacon.

Pamela.

It was about 1pm. I would never have seen her out before eleven. She was nocturnal. When you saw her in the daytime, it was as if you’d awakened a sleeping owl. Daytime was alien to her. It always seemed as if she were adapting to it. The expression, “groping in the dark” needed to be “groping in the light” for Pamela.

“Pamela!” I said.

She blinked, found the source of the words. Then, recognizing me, she laughed a beat or two.

I walked up to her.

“Hi, hello,” she said. Once again, I realized how tall she was, probably 5’ 10”. It was difficult to say because of the fullness of her hair.

“What are you up to?” she said.

“Taking a walk. Such an incredible day. What about you?”

She had on a navy-blue pea coat. She wore a silk scarf tied in a series of complex, appealing swirls about her neck with a broad blue ribbon around the back of her hair. She always dressed with flair, with panache. I used to ask her, “How do you always dress so well? If I gave you a pair of galoshes and a toenail clipper for clothes, you’d look great.”

She’d laugh—again, one or two beats. “I don’t think about it.”

So, there she was. When I said the word “walk” to her, she frowned slightly. She was not fond of exercise.

“Yes, yes,” she said. “You love to walk. I know. I pity you. I’d rather take a cab. I’d take one to cross the street if I could.”

“I know you would. New York taxi drivers should give you an award, or something.”

“I’m still waking up,” she said. Just behind us, looking like a castle waiting to be sieged, was the Jefferson Market Library. A big, red brick anomaly that I loved. I glanced at the library clock. It was one-fifteen.

“What are your plans for today?” I said.

“I’m meeting Wilhem for brunch,” she said. She had the wan skin of redheads.

“Wilhem?”

“Didn’t I tell you? I’ve got a new boyfriend. I’m in love.”

“Wilhem? What’s that name?”

“Dutch. He’s Dutch.”

“How’d you meet him?” She was right, she hadn’t told me about him.

“I met him at a party. I’m a goner. He’s going to ruin me.”

“What’s he do?”

“He does lots of things. Right now he works in a gallery in Soho. He’s got lots of ideas,” she said.

“I’d like to meet this guy,” I said.

She continued her half-convincing lament. “I’m a goner. I’m like a teenager. I can’t think straight. Help me. I’m his sex slave. It’s pathetic.” She laughed at herself.

I couldn’t help but think of that Joni Mitchell line, “Help me, I’m falling in love again.”

“Pamela,” I said, “it sounds like it’s a little too late for help.”

“Too late,” she said, as if repeating some kind of curse. “Too late. Yes, it’s too late.”

I’d heard this once or twice before. When she fell, she fell hard. Often, she’d disappear for weeks, caught in the thralls of romance. I was envious of her abandonment, of her relinquishing everything for love.

“You like this, Pamela,” I said. “Admit it.”

“Part of me does. Part of me is scared out of my mind.”

She’d gone to boarding school in Switzerland and learned to speak fluent French, down to the little pursing of the lips, producing those sounds that are nearly impossible for most Americans to create. She was sophisticated in a European way, without the imperiousness. She was smart, funny and buoyant, but you could see a weighty unhappiness emerge from time to time. She wasn’t self-indulgent, though, complaining or moaning. She was almost always in a good mood. I liked her very much.

“I’ve got to go,” I said. “I’ve got to get on with my walk.”

“Call me,” she said. “I want to talk to you about Fair Harbor. You need to commit. You need to do this. Don’t blow it. Really. Do this.”

She was talking about the house she and some friends were going to rent on Fire Island for the summer. I was dubious. I liked being in New York during the summer. But Pamela was adamant. “This will be good for you,” she said. “Trust me on this. I mean it. Don’t say no.”

“I’ll call you later,” I said. I turned and started to go west on Eleventh Street.

“Call me!” she said, raising her voice so I would hear as I walked away. “Save me from love!”

I left her there in her predicament and went off on my Saturday walk. There was still so much to see. The city unfolded in front of me, foot by foot, slowly moving by me as I walked. Walking was the best way to know the city. Once I walked it, it was imprinted inside me. I continued west, crossed Seventh Avenue and then went down West Fourth Street. I was going to turn left on Perry or Charles, each beautiful streets, and head toward the Hudson River. Which one? Those small, on-the-spot decisions were, in part, what made me feel like an explorer in an undiscovered country.

I thought of Pamela. She might claim to be helpless, but, unlike me on this sharp fall day, she was in love. All that exciting turmoil, all that newness and doubt. When everything is the first time, when you’re giddy and nothing or nobody else matters except the two of you. Time is meaningless. Your vision is narrow—closed, even. You don’t care what happens in the world. I didn’t have that, and I didn’t know if I ever would. But on this crisp autumn day, I had New York. I loved it, and I felt it loved me back. Today, that would be enough.

September 10, 2022

Your handyman

I recently moved to a house in the country. A very old house. Very deep in the country. In rural Louisiana, to be exact. I moved in with my girlfriend. It’s her house. It was her parents’ house and her grandparents’ house before that. It’s been moved at least once. It’s small—about 800 square feet. It needs a lot of attention. Like me, it needs work.

I soon found this out. It didn’t take long for the house to reveal its true self. Things needed to be fixed, changed, replaced, etc. If it were a person, it would need a hip replacement, knee replacement, pacemaker, cataract surgery, hernia operation, hearing aid, maybe plastic surgery, not to mention haircut, manicure, new wardrobe, better diet and teeth whitened.

Lots of stuff.

I do not know how to do this stuff.

For the past 45 years I’ve lived in cities. In apartments, to be precise. I never had a back yard, a roof that was mine alone, a garage, a porch, an attic, a basement. I never owned a stove, a refrigerator, an air conditioner. They all came with the apartments. I never had to fix anything. For that, in New York, there was the superintendent. In New Orleans, the landlord. Any leak, drain problem, heating loss, stove anomaly, I called the super or the landlord. They came with their toolbox. They fixed things. For forty-five years, it went like this. And, for the most part, all went smoothly.

Not just that. I don’t know how to fix most of these things. I never learned. Cue chagrin emoji.

Now, with the house, there is no superintendent or landlord. They are me. Plus, the things that need fixing go far beyond clogged drains. (I actually fixed one of those in the house! Well, she did.)

A new sink and vanity was needed in the bathroom, for instance. The old one did not function at all. So we went to Lowe’s and purchased a new one. One small detail! The sink and vanity needed to be installed and the old one removed. Plumbing and carpentry would be involved. Electricity, too, because we wanted a new light for the vanity/sink.

The men we found online who arrived to do that were capable. I could hear and see their experience in the questions they asked between themselves and decisions they made.

I stood by in admiration, wonder and face-reddened envy.

Not to be able to make the most basic repairs and, beyond that, to fix things that any self-respecting—yes! Here it comes!—man should be able to fix puts things in perspective, quickly.

It didn’t seem appropriate at the time to sing out, “Hey guys, I can write a good, solid sentence! Want to hear one of my latest?” Art in the end doesn’t do anything practical. It has its benefits, true. I wouldn’t have devoted my life to it otherwise.

But some days I just want to be able to install a damn sink.

Everything about it is satisfying. When you’re done, you look at it and think: anyone can see what a good job this is. It works well. It looks good. Yes, anyone can see that.

And I can say I did it.

September 4, 2022

Mad Man

Chicago, 1972. I was at the Leo Burnett Advertising Agency for an interview for a copywriter’s job. I had been working in Detroit in that capacity, was let go along with a score of others one day. Cutbacks, was, I believe, the term they used. I’d sent my portfolio of ads to Burnett, and they told me to come to Chicago, and they’d see. Leo Burnett was huge, and famous, and one of the few ad agencies outside of New York that retained big clients. So, to Chicago I went.

I remember very little of this encounter except one moment that has stayed in amber.

I was talking with a mid- or low-level man at the end of a long day of interviews. He was extolling the virtues of Leo Burnett and its eponymous founder. Ad agencies often have a cult of personality about their long-gone founders, displaying them proudly like preserved communist leaders in rotundas. I still hoped I might get the job. (I did not.) So, I had a frozen smile on my face, and I kept nodding at everything he said like a bobble-head doll.

The man was in the middle of praising the agency when he looked over my shoulder and stopped talking.

I turned and saw another man approaching us. He was tall, easily six feet, and likely two or three inches taller. He was perhaps in his fifties. He looked tired. Weary is probably the more precise word. He had an overcoat slung over his shoulder that he grasped with one hand. With the other, he carried a briefcase. Much later, when I thought about all this, he made me think of Willy Lowman. He had that same tired, weight-of-the-world-on-his-shoulders look as the main character from Death of a Salesman.

The man walked slowly toward us. My interviewer said,

“Good night—-”

I don’t remember the name.

The man said goodnight back. He didn’t pause. He continued down the hall, walking away from us.

“Do you know who that was?” my interviewer asked.

“Uh, no.”

“That man….”

He paused.

“That man.…”

Yes, yes?

“That man created…the Jolly Green Giant.”

I looked down the hall, and, just in time, I saw the man, coat slung over his shoulder, slowly turn a corner, and then disappear.

August 29, 2022

Christy Lorio

A former student of mine, Christy Lorio, announced on Facebook that she has six months to live. Or perhaps less than that, according to her doctor. She’s had cancer for almost five years. She’s written about it, been public, posted her various ups and many severe downs on Facebook through the years. It was painful and inspiring to read about her battles. Painful because they were harsh and relentless. Inspiring because Christy has never stopped living creatively, vigorously, optimistically. She was—and still is—a writer, then became a photographer, enrolled in master’s degree program in photography and chronicled others who have cancer and how they deal with it. Since taking up the camera, she’s had 15 gallery shows.

Just over a week ago Christy announced on Facebook that she and her husband were celebrating their 18th wedding anniversary together. “We’ve had a good run, Thomas Fewer. I hope we get a few more years together.” Then this most recent dark news.

I met Christy in the spring of 2014 in a class I taught at the University of New Orleans, “Introduction to Creative Nonfiction Writing.” I remember the class, and her, very well. She was a serious, dedicated student with some flamboyant tattoos—was it a snake of some kind?—on her arm and a steely desire to write. She didn’t have the tenacious, cruel cancer she has now. I have all her writing from that class—and all her writing from the four other classes I taught that she was part of as well. I wish I could give you great portions of it now, but I can’t without her permission. I don’t feel now is the time to reach out to her about that. I can only quote a few words with a clean conscience; fair practice it’s called in the arts.

I will tell you that the first writing she turned in for that 2014 class was a very funny, deft piece. It was about a pair of shoes she wanted to buy that her mother refused to let her purchase, because they were “hideous,” according to her mother. Christy, a high school student in a Catholic girls’ school then—read mandatory uniforms—bought them anyway and wore them at—not to, because her mother would have seen that—school. The piece was far more than a humorous mother-daughter fashion battle, though. The shoes symbolized Christy’s feeling she was an outsider, standing apart from the crowd, with different goals, wishes and aspirations. Wearing the shoes she dubbed “Blue Laser Beams” with “the veneer of a diner seat booth,” was her way of declaring who she was. She ends the piece this way:

“As for my beloved blue sparklers, the dingy white soles fought a long, hard battle with crazy glue and eventually, I took them off their sticky life support and give them the proper burial they deserved in the trash can. Still, I haven’t lost the spirit that went behind their purchase in the first place: don’t compromise who you are for anyone.”

I remember reading this piece and thinking, “Now, here’s a writer.” It’s so difficult to write humor and to write it well. It requires a linguistic dexterity and a sharp attention to rhythm and word choice. I couldn’t wait to read more of her work. I felt that way then. I’ve just re-read the piece. I feel that way now. It’s still funny. It still moves me the way it did eight years ago. I suspect you would have the same reaction.

At one point, and I don’t really remember when, I found out she had cancer. I knew that her father had died of cancer, and so it was in the family. She feared she might get it, and she did.

She became very public about her disease. She posted about her chemo, her operations, her pain, her fierce determination to live. At one point, after she’d taken up photography seriously, she had a benefit to help cover her hospital bills. Cancer is not only destructive, it’s expensive. She was in the middle of one of her chemo regimens when she had the benefit. I went and bought one of her photos. I also met her mother there for the first time—the same mother who had dubbed Christy’s shoes “hideous.” I teased her about this. But I saw the fear and worry in her eyes when she talked about her ailing daughter.

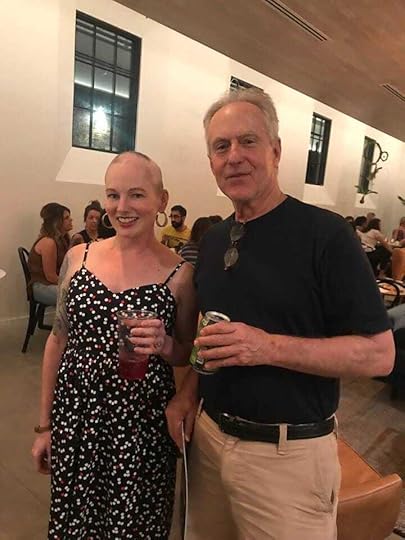

With Christy at her gallery show

With Christy at her gallery showAs the years went by, and her cancer periodically calmed, and then rose up and raged again, her battle became heroic. At least that’s the way I felt about it. Again and again, the cancer would be staved off, only to return. She had—how many was it? Two, three?—brain operations. Other operations. Chemo, then again chemo. Failing eyesight, loss of balance, more operations. I followed her journey on Facebook, and I realized at a certain point that I’d never met anyone as brave. Her determination and optimism were so fierce, I thought she would kick this detestable thing. She knew she had a terrible disease. But you could see she put every ounce of her strength and will into fighting the cancer. I thought, if anyone can beat it, she can. And she came close—it seemed. There were periods of the cancer waning, when her life seemed relatively sane and normal. I think all of us who read her posts about recovery raised a collective cheer. She’s going to beat it! She deserves to beat it!

But we all know cancer is sly and resourceful and, ultimately, so many times, finds a way back in.

In her most recent post on Facebook, there was a characteristic absence of self-pity : “Thanks so much for the support, everyone. I shot my first wedding yesterday afternoon. It was nice to do something normal and take my mind off things.”

She’s still here.

If you want to help Christy with those hefty medical bills, she has a site on “Buy me a coffee” where you can contribute. Please consider that.

August 26, 2022

Don't be a summer literary soldier

From time to time I see people turning on their literary heroes. Writers who they used to praise to the skies, they now condemn in the harshest way. Ernest Hemingway comes to mind. Once esteemed and lauded, there came a time when he was rejected, even ridiculed. That’s still going on. Most of this condemnation I believe comes from people not approving of Hemingway’s life, his feverish pursuits of bullfighting, big game hunting, etc. I think at times it’s only marginally about his writing. I would bet some of the detractors haven’t read a word of what he wrote, or very few. I would also bet that some of these grand inquisitors actually admire Hemingway’s writing but feel that, for political reasons, they have to join the mob of ostracizers.

It’s easy to join the mob. It’s easy to bask in the sanctimonious pillorying of an artist when you’re part of a group effort.

“Why the Hell Are We Still Reading Ernest Hemingway?” is the title of a 2018 article in the Daily Beast.

It takes courage to say: I don’t agree with the mob. I stand by my love and admiration of this writer. Now and forever. Why? Because of the writing. Because it’s good. Because it always will be good.

It takes someone with guts and eloquence.

Like Joan Didion.

Didion wrote a powerful, unambiguous homage to Hemingway’s writing titled, “Last Words,” in the November 9, 1998 issue of The New Yorker. The essay is to a great extent about the effort to publish, posthumously, work by Hemingway that he did not approve for publication when he was alive. For a while, that became a cottage—or, better put, a skyscraper—industry with EH’s unfinished work. It was always about money, not literature. Didion takes those publishers and editors to task.

The essay is also about the power of Hemingway’s words.

Didion starts the piece by quoting the famous beginning to A Farewell to Arms:

“In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels...”

Didion writes, “So goes the famous first paragraph of Ernest Hemingway’s ‘A Farewell to Arms,’ which I was moved to reread by the recent announcement that what was said to be Hemingway’s last novel would be published posthumously next year. That paragraph, which was published in 1929, bears examination: four deceptively simple sentences, one hundred and twenty-six words, the arrangement of which remains as mysterious and thrilling to me now as it did when I first read them, at twelve or thirteen, and imagined that if I studied them closely enough and practiced hard enough I might one day arrange one hundred and twenty-six such words myself.”

Is there a more clear, more straightforward expression of praise than that?

Hemingway in Africa

Hemingway in AfricaDidion was aware of the aspects of Hemingway’s outsized life that the mob objected to:

“We have seen the snapshots: the celebrated author fencing with the bulls at Pamplona, fishing for marlin off Havana, boxing at Bimini, crossing the Ebro with the Spanish loyalists, kneeling beside ‘his’ lion or ‘his’ buffalo or ‘his’ oryx on the Serengeti Plain.”

Nevertheless. Nevertheless, it’s the writing that counts in the end: “…we sometimes forgot,” she writes, “that this was a writer who had in his time made the English language new, changed the rhythms of the way both his own and the next few generations would speak and write and think.” She concludes, “This was a man to whom words mattered. He worked at them, he understood them, he got inside them.”

No summer literary soldier she.

What do I feel about Hemingway? I think he was a great writer who widened horizons for both readers and writers. I’m with Didion: he understood words. He used them with a precision that can still elicit awe. He taught me a great deal.

It’s not just Hemingway, of course, who has had their door pounded on at midnight by the torch-bearing mob of those who would “correct” our literature.

David Denby put it well in a 2012 article about the great Ralph Ellison,

“The reputation of ‘Invisible Man’ has suffered no serious hits over the years. Yet Ellison’s reputation as a man is in very serious danger. Eventually, in our culture, where literature is of relatively little importance, and gossip and personality matter enormously, the book may come to suffer by association with the artist who created it.”

In a 2020 article in The New Yorker, “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” Paul Elie declares that O’Connor’s remarks outside of her writing “belong to the author’s body of work; they help show us who she was.” Evidently, the work no longer speaks for itself.

Others may seek the safety in numbers of the politically correct. I hope I will always speak up, will defend my literary heroes when the horde goes after them. I hope I have the courage to follow the example of the stalwart Joan Didion.

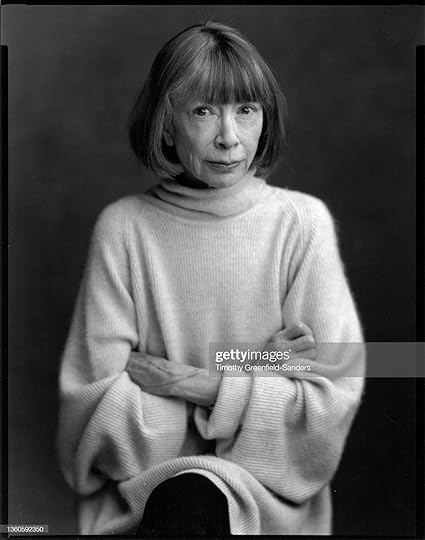

Joan Didion. Photo taken in 1998, the year she published her essay on Ernest Hemingway.

Joan Didion. Photo taken in 1998, the year she published her essay on Ernest Hemingway.

August 20, 2022

A traveler's dilemma

I was in Maine yesterday. Today I’m in Louisiana. The change was and is disorienting. I climbed in a plane. I sat there for four hours. I got up. I walked out of the plane and then out of the airport into another culture, another weather system, another time zone, another way of talking, different flora and fauna, food, history, another way of life.

My mind and body has had a hard time adjusting. I’m not the first to report this sensation, I know. In longer trips it’s called jet lag. But that’s not precisely what I’m talking about. I’m talking about leaving.

I was in Camden, in Mid-coast Maine. It’s a stunning part of the country. I’ve never encountered this particular mix of rock, sea, hills, trees and air anywhere else in the United States. Not in New Hampshire, the only state that borders Maine, or in Vermont, one state over. Or anywhere. Maine is unique. I always fall under its spell when I’m there. In the late summer, the produce raised there is about the most perfect there is. Maine is perhaps the greatest undiscovered food paradise in the US. People know it for lobster, but even without lobster—and I have less and less a yearning for it these days—the variety and quality of the food is astonishing.

Summer produce typically sold at Chase’s in Belfast, Maine.

Summer produce typically sold at Chase’s in Belfast, Maine.I spent my last three days staying at my friends’ house, perched high on one of the hills Camden is known for. It’s an isolated place, and I had their small forest all to myself. I walked among their trees. So much has been written about trees lately, and so much of it is good. I walked the trails on my friends’ property, and looked at the trees, each with its own nobility, and wisdom. How can so much dignity be growing in silence, unobserved? It’s there, for years and years. I feel, looking at them, that they have the answers. They know.

Pine trees on my friends’ land.

Pine trees on my friends’ land.I saw some deer on that high hilltop in the morning and in the evening, cautious and so beautiful I fell in love with them and would have gladly joined them if they’d let me, simply because they are so graceful and lovely.

Sunset in Maine where I stayed.

Sunset in Maine where I stayed.I left mid-morning. It was raining. I drove my rental car back to where I’d picked it up, and then my ride took me to the Portland Airport. Who likes to travel anymore? I mean the actual traveling itself. I love getting places, being there, to be sure. The process is another matter. I knew it would be a long day. Arriving late evening—if I was lucky.

I was. I arrived in the Lafayette, Louisiana airport very nearly on time. In this day and age of aggrieved passengers with missed or cancelled flights sprawled on airport floors trying to catch some sleep, I count myself lucky. I’m sure there will be payback later.

I hadn’t seen my girlfriend in ten days, and she was a lovely sight with her beautiful smile and kind heart and long silver hair. I walked out into the sticky Louisiana evening but my mind and body were still in Mid-coast Maine with its temperature nearly twenty degrees lower and its humidity not insane like it is here where I live.

Even today, nearly twenty-four hours after leaving Maine, I’m still there. I’d fallen in love with the land again, and I felt disloyal and awkward discarding that place like it was a candy wrapper or a bottle top. My affection for the place hadn’t waned. Yes, I wanted to be in the arms of my girlfriend. But her love is a different kind of love than the love I have for Maine. I gave myself to the place. Then I left it. Abruptly. I’m having a hard time saying farewell in a way that makes sense. I guess life is made up of goodbyes. It’s just that an airplane flight is a cold and abrupt way of doing it.

August 14, 2022

All the world's a stage

I was teaching a writing course in a town in mid-coast Maine. The school where I teach put me up in this house as part of the deal. It’s a wonderful house, with a forever-sloping lawn that ends at woods that have tall birch trees whose leaves flutter in the wind and stir the heart. The house has many windows, and two decks. From one of them, I saw three deer early yesterday morning as they walked easily across the vast lawn. They entered, one by one, with enough pauses between entrances to make it seem choreographed. Then they were all there. One was a fawn, with the classic, ahh-inspiring white spots.

The adults, stately, alert, paused, bent their heads and went at the grass for a time. None of them had antlers, so I assumed they were females, but perhaps one or two was a juvenile male. I don’t know enough about deer to be sure.

I was standing stock-still on the deck looking down, but they raised their heads at moments and looked my way. They seemed to know it was a human up there. It could have been my loud checked pajamas I was wearing that alerted them. They kept their eyes focused on me, and, after a minute or so, decided I was something to be wary of and trotted off into the woods. The fawn, feigning bravery, lingered for a few seconds, but, seeing the adults gone, suddenly reverted to helpless child and dashed urgently after them, leaving just empty lawn.

It always amazes me that this animal, a deer, so common in the northeast, can make me feel surprised and elated, as if I’ve just seen an African gazelle or impala. But it does.

There is something perfect about a deer, beyond the perfection any animal embodies. It’s coat—at least the coats of these deer—is sleek, smooth and tan, without a flaw. It’s face is sloping, delicate and graceful, like a ballerina’s profile. In fact everything about those animals was balletic. They were like a small dance troupe that wandered across the stage, the lawn, in complete possession of the moment, paused to give me a glimpse of their trim bodies in action, and exited.

It wasn’t even 7am.