Richard Goodman's Blog, page 18

August 6, 2022

Entering a new country

I look in the mirror, and I’m startled. My body is gaunt. I’m developing one of those old-man bodies you see on the beach. Bones everywhere. You could hang clothes from my collarbones. I am so close to my skeleton now. I am seventy-seven. 77, to be abundantly clear. Old by official standards. Old enough to have a senior citizen rapid transit card and AARP membership to prove it. What fear and loathing I have of that word—old. It makes me angry. And defiant. And scared.

Old means slow, forgetful, dull, doddering, and weak. And perhaps worst of all, complaining. How am I going to contend with this? How am I going to manage growing old, aging, being old? I am a traveler who has crossed over a drawbridge into a strange and unchartered country, a stranger in a strange land. Everything about this country, this commonwealth of aging, is new to me. What are the customs here? What is its culture? Old. How do I act? How can I be a good citizen? How can I be brave and good-natured and still contribute to the world? How will I deal with the inevitable assault and battery on my mind and body?

In this new land, I look around for a guide, for someone to tell me how to act, what to do. I see no one. I ask my fellow ancients for help and advice. They have none. They’re just as unprepared as I am. We look at each other in confusion. What happens next?

I look longingly at that drawbridge I recently crossed. I see people I know back on the other side. I see landscapes I’m familiar with. Landmarks. I spent a great deal of time there—my life, so far. But that is a land I am no longer given access to. I go to the bridge and ask the officer at the gatehouse if I can cross back over. Sorry, he says, not anymore. He looks at his watch. “You’re still in time for the early bird special here, though,” he says, smiling.

I encounter some people who ask me enlightening questions. “Is everything functioning well? And that includes you know what.” It is, I reply. “Is you daughter healthy and thriving.” She is. “Do you have friends?” I do. “Do you still laugh?” As often as I can. “Have you kissed a woman recently?” As a matter of fact, I have. “Did she kiss you back?” She did! “Have you seen a Chestnut-sided warbler recently?” In July. “Are you still able to cry?” I can. “Are you still curious? Are you learning new things?” Every single day. “Have you taken a hot shower today?” This morning. “Did it feel good?” Heavenly. It felt heavenly.

I thank them for their gentle reminders. I take a deep breath. Then another. That’s enough. That’s more than enough.

July 31, 2022

My own private Gutenberg

In 1957, my Uncle Bob gave me a Smith Corona Galaxie II Manual Typewriter for my twelfth birthday. It was one of the best gifts I've ever received. It was the most loyal, steadfast companion through my years of struggling to write. Always there, no matter what time of day—pre-dawn, mid-day, early afternoon, late night—ready, willing and able. I would open the clunky metal case, and those white keys were poised, at strict attention, as if to say, "Come on! Go ahead, just pound those keys! That’s what I’m made for!"

And pound those keys I did. I type with two fingers, but I type with a vengeance. I type hard. It’s almost as if I'm furious at those keys. I love typing like that, with gusto, and I believe that’s the way manual typewriters are made to be used. When I strike a typewriter key, I feel a link to Gutenberg and his press. The key you strike in turn activates a slim metal arm, the head of which slaps hard against the page. It makes an impression of a single letter, a dark inky impression. The impressions even bleed slightly; they're inky blossoms.

I typed I don’t know how many thousands of pages on my Galaxie II typewriter through the years. I typed the manuscript of my first book, and I remember holding it lovingly before I sent it off to my agent. It was just 100 pages at the time, eventually grew to be 203, but it was all typed, every single letter, every word, slapped on the page by me and my Galaxie II. I typed essays. I typed poems. I typed stories and laments and so many bad pieces of writing, but even bad writing has a kind of basic dignity to it on the typewriter. Try it, if you don’t believe me. This very sentence—written heretically on a computer!—would have a rough, unique elegance if it were typed.

My typewriter stood up astonishingly well under all the irate and passionate pounding I subjected it to. Strong as an ox. Stronger. But once in a while, something happened. The head of an arm just couldn’t take my abuse anymore and gave up the ghost, tumbling off along with the letter it represented. I’ve seen “P” wounded gravely. I’ve seen “S” die. I’ve even seen “!” get very ill. When that happened, I took my Smith Corona to a typewriter repair shop with all the worry and fretfulness of a cat owner bringing his sick pet to the veterinarian. And I had the exact same question asked with the exact same tone, “Can you…make it well?” Luckily, having lived most of my writing life in New York City, there were several reputable and reliable typewriter docs who gave my Galaxie II the expert care it needed.

I kept it for forty good years, until, finally, it collapsed and gave up the ghost. It had gone through many operations, transplants, bypasses, and shunts until its poor body just couldn’t hold up any more. I hardly recognized it at that point, it had so many additions from so many other machines—terminally ill typewriters that had selflessly donated their metal organs so that my typewriter might live. Still, it was a dark day when, with great sadness and solemnity, I let it go. I still think about it, even now.

Smith Corona Galaxie II, thanks for the great ride.

July 26, 2022

Pickleball

I joined a group of pickleball players yesterday. They’re called “The Agin’ Cajuns.” (I live near Lafayette, Louisiana, the heart of Cajun country.) This name is a takeoff on the better-known expression “Ragin’ Cajun,” a term that has been applied to political consultant James Carville, himself an actual Cajun.

Do you know pickleball? It’s a court game that’s played with paddles and a plastic ball with holes, much like a whiffle ball. The court is about half the size of a tennis court. The idea is basically the same as any court game with a net. Return the ball over the net without it letting it hit the court twice on your side. There are variations in its rules, but the principle is the same.

The slower speed of the ball and the small court make it a game that is more inclusive than tennis. In just about every way, including age. I had played pickleball—the origin of the name is disputed—in Maine and Denver. I moved to this part of Louisiana recently, and I was looking for a way to meet people and to get some exercise. I found the Agin’ Cajuns on line. So, yesterday evening I went, my brand-new paddle in hand, to play pickleball at the Thomas Park Recreation Center in Lafayette.

I walked inside, and there they were. About forty Agin’ Cajuns in a gym playing on three courts. Four people were playing on each court—doubles—for fifteen minutes at a time. The first thing I noticed was that they were, indeed, agin’. Except for a few players, most everyone looked at least sixty and some were clearly in their seventies. I later learned one woman was in her eighties. The thing of it was, they were all playing hard. And well.

Some agin’ pickleball players. (Image courtesy of AARP.)

Some agin’ pickleball players. (Image courtesy of AARP.)I put my paddle in line to play and watched the others go at it. I hadn’t played in months, and I was clearly going to be rusty.

I’m seventy-seven, by the way. I’m not a Cajun, but I am agin’.

While I was waiting to play, a man came up and started talking to me. I’m sure he saw I was a new face. He informed me he was a former surgeon. He asked me what I did, and I told him I was a writer.

“Oh, an author. Have I read any of your books?”

“Well, I don’t know,” I said. “I hope so.”

“Are you successful?”

“My first book is still in print,” I said. “That’s all a writer can hope for. I just want my books to stay alive. Like I’m sure you do with your patients.”

“They’re all dead.”

Deadpan delivery.

He walked on to talk to someone else.

Another man claimed he recognized me.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I just moved here.”

He looked dubious, as if I weren’t telling the truth.

“No, I think I know you.”

I watched the eighty-plus woman play. She was moving about with agility and pep. She finished, got her stuff, and as she walked off the court, she said to someone,

“I played tennis all day earlier!”

As she exited the gym, I turned to the person next to me and said,

“She’s off to rollerblade.”

He laughed.

My turn to play.

Three women and me. I apologized in advance about my lack of expertise.

“Do you know how to play pickleball?” my new partner asked, eyebrows arched.

“Well, I know how to play, but that doesn’t mean I can play well.”

“That’s ok. As long as you know the rules. I played with one guy who didn’t even know what pickleball was,” she said with some disdain.

We began. It was clear I hadn’t played in a while. I flubbed a lot of shots. My partner clearly wanted to win. On several occasions, she turned to me after she had returned a ball and declared, evenly,

“That was your ball.”

I actually got winded playing. I was nervous as hell, but I enjoyed myself.

The other team won.

“You did fine,” my partner said. I heaved a sigh of relief.

I sat down, feeling like a kid who had just been praised by his little league coach. Does the need to be accepted and validated ever leave us?

A man walked up and began talking to the man next to me about their hip replacements.

“Who did yours?”

“Ballinger.”

“How’s it feel?”

“Good. He did a good job. You?”

“Stromley. I’m doing well.”

I felt a bit inadequate that I hadn’t had an operation myself and vowed to get one soon.

My turn to play again.

Again, I was with three women.

This time I played better. I was fortunate to have a very good player as a partner. She was younger than me and the two women on the other side of the net. She took the lead, often poaching on my side of the court and crushing the return. She had the cold clear look of a killer. We like a killer on our side. I played decently, returning the ball the few times she let me. I was less nervous. I was actually enjoying myself.

We won.

I sat down next to the man who said he thought he recognized me.

“Do you have a red car?” he asked.

“No. Green.”

“Are you sure?”

Two games were enough. My body was speaking to me. Not in Cajun French but in plain English. “You need to go home,” it said.

Before I did, a woman approached. She was handing out little flyers about an upcoming tournament. I asked for one.

“Are you a member of the Agin’ Cajuns?”

“Well, I signed up for the newsletter.”

“That’s not enough. You’re not an Agin’ Cajun until you pay the $12 yearly fee. Have you?” She withdrew the flyer she was about to hand to me.

“Uh, no. Not yet. But I will!”

“You promise?”

“Yes! Yes! I promise!”

She handed me the flyer dubiously.

I took it. I grabbed my paddle and water bottle, and said goodbye to those next to me. The man who thought he recognized me pointed a finger at me with a small, knowing smile, nodding his head as if we shared a secret.

“See you next week,” I said to anyone and everyone.

And I meant it.

July 21, 2022

The terrible infant

It's surprising to find yourself, or something you've written, as a source for part of a famous dead poet’s biography. Especially a famous dead poet with an exotic, volcanic life. I’m speaking of Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891).

I wrote an essay for a magazine about Rimbaud's time late in his short life as a coffee trader in Ethiopia, about how he got there, unlikely as that was. I was thinking about writing something else about Rimbaud recently, so I promptly went to everyone’s convenient source of choice, Wikipedia. Lo and behold, there it is, citation number 72, a reference to the article I'd written twenty-one years ago and nearly forgotten.

It made me think of how strange it is the places we end up in our lives. Here was this enfant terrible, possessed of extraordinary poetic powers, who ended up in Harar, in what is now eastern Ethiopia, having abandoned poetry forever some fifteen years earlier, counting his money, forever concerned that local merchants were cheating him out of a few pennies, or whatever currency they used.

But that’s not the way it began.

Arthur Rimbaud

Arthur RimbaudHe sprang full blown as a poet from a small city in northern France. He was writing lasting poems by the age of sixteen. Arthur Rimbaud was a poet whose life was like one of those Roman candles that goes astray and sweeps erratically across the sky with the possibility of crashing into a house or a person or you. Everything about his life was dramatic, self-destructive and extreme.

He wrote incendiary, sometimes gorgeous, sometimes fearlessly sexual, sometimes frustratingly complex, and, at times, incomprehensible poetry in the remarkably brief period he wrote poetry. Which is to say, from the age of sixteen to the age of nineteen or twenty. His most famous poems are "The Drunken Boat" and "A Season in Hell." I prefer poems like his early, exquisite, “Au Cabaret Vert,” “The Seekers of Lice” and one of the boldest depictions of early sexuality, “Memories of the Simple-Minded Old Man.”

Nothing had ever been seen like this in French poetry before, even from Baudelaire. After the age of twenty or so, Rimbaud stopped writing altogether. No one knows why. The rest of his life, he was a wanderer. He went in search of something he could never find, because it wasn't there. He looked for it in Paris, in Indonesia, in London, in Cyprus, in Yemen. And, finally, in Ethiopia.

One of his last efforts was “Illuminations,” forty-odd prose poems it seems he wrote mostly when he was in England. No one understands them. Some people claim they do. Read a few, and see for yourself.

Rimbaud by Picasso

Rimbaud by PicassoSome artists love Rimbaud because his chaotic, fiery life gives them validation for their own self-generated chaos. I am sometimes a passenger on that ship. And Rimbaud's life was as chaotic as any self-destructive American artist's has been, if not more so. Typical is the affair he had with the (married) poet Paul Verlaine that ended with Verlaine, in a rage, shooting Rimbaud in the wrist. As Allen Ginsberg said, "Rimbaud seems to be a complete turn-on catalyst to every poet in small town isolated, or big megapolis, staring at the city lights over the roof." What that means to me is: don't let those small-town minds stop you from becoming the comet that you are. So you destroy a few things, or lives, along the way. You're an artist. Yes, an artist! A pass for crashing through life! But, really, Rimbaud harmed himself more than anyone else. Verlaine, after all, was responsible for his own life and marriage.

Rimbaud in Ethiopia, self-portrait

Rimbaud in Ethiopia, self-portraitThe last years of his life Rimbaud spent exporting coffee from Ethiopia—an astonishingly able linguist, he learned the two languages spoken there, Amharic and Harari, quickly—and smuggling guns. All he cared about was money. He took up photography. In those later years, someone realized who he was (Rimbaud had become famous in Paris without knowing it) and asked him about his poetry. "Disgusting!" Rimbaud replied.

One of his last letters, written to his sister from a hospital in Marseille, where he was soon to die at the age of thirty-seven, says, "Our life is a misery, an endless misery. Why do we exist?"

July 14, 2022

The shoe store

I was looking for a pair of shoes. Very specific. I’d bought them ten years earlier in the same store on West 72nd Street in New York City. They didn’t make that particular shoe any more, but I wanted something as close as I could get.

The woman who came to help me was maybe fifty, with curly, russet, Annie-like hair. And a kind, accessible look. You know, don’t you, when there is a bright soul inside. You can see it on their face. Undeniable. I told her what I wanted. The brand, size, color.

She came back with three boxes.

“I don’t have that size in the color you want, but I have these you can have a look at.”

They weren’t what I wanted. Well, ok, maybe I’ll try this one. But, no, too large. She didn’t push me, though. She was selling, but not hustling. It was all very human.

We got to talking. I’d been listening to the other salespeople—none under forty—bickering while she was in back getting my shoes. One salesperson said to another, “Stop saying that! You’re stressing me out!”

When my saleswoman returned, I said, “This sounds like a Yiddish theater group in here.”

“You have no idea,” she said.

I don’t know how the conversation veered, but she told me she’d been an actress.

“I was in the touring company of Cats for six years.” She broke out into an enormous smile. One of those smiles that lift you out of your seat and shoots a dosage of optimism straight into your veins.

“Cats? Really? What role did you play?”

She didn’t answer directly but said, “I’m a singer. I love to sing!”

“Did you like being in Cats?”

“I loved it!”

Through the thirty-five years I lived in New York, I met many actors, many young men and women struggling to be actors. Only a few few made it. Most quit. It was too damn hard, too discouraging.

“Did you have any other roles?”

“Yes. My last show was Menopause. It was a musical.”

“They made a musical about menopause?”

Did they! I looked it up. It ran off-Broadway for four years. It’s toured all over the world—Croatia, Brazil, Malaysia, Finland. The Las Vegas show has been running for sixteen years. Typical songs, “Change, Change, Change” to the Aretha Franklin tune; “Puff, My God, I’m Draggin’” to the Peter, Paul and Mary song; “My Thighs,” after the Mary Wells hit.

I guess I missed something.

Now, we were beyond shoes. We were just talking. She told me about opening night at Menopause. The woman in charge of the show told her, just before she was about to go on, that everything she did was wrong.

“I was going to perform in front of all the critics! And she said this to me. And I hadn’t done everything wrong!”

Sometimes you want to kick someone in the groin. This was such a case. Opening night. When you’re fragile as a house of cards. What is it with people?

“I quit acting after that,” she said. “I couldn’t take the BS anymore. I love singing, though!”

She then wrote down the exact shoe model and name for me on a card, along with her name, Jackie.

“You might be able to find the shoe in another store. This way you won’t forget what it is.” Most likely guaranteeing not a sale. That high wattage smile again. I was basking in it, tanning in it, growing in it.

I had to go. Meet someone. I didn’t want to, though. I wanted to stay. What I really wanted was for her to sing, right then and there. I wanted to say, “Sing me something, Jackie! Sing me a song from Cats or even from Menopause. I want to be your audience. I want to be your biggest fan. I don’t want to leave your smile. Turn this shoe store into a musical theater.”

It’s so hard to be an actor.

“It was nice talking to you,” she said. I said the same.

I walked out of the store, feeling my step lighter, as if I were wearing a brand new pair of shoes.

July 9, 2022

The courageous Jean Rhys

Nobody writes like Jean Rhys. Comes near it.

She defies categorization. If you read her books, Voyage in the Dark, Good Morning, Midnight and After Leaving Mr. Mackensie, for example, you may find yourself unable to think of any other books to compare them to—except another book by Jean Rhys.

She may be best known for her book, Wide Sargasso Sea, a follow-up to Jane Eyre. But that book is not what I think of when I think of Jean Rhys’ writing.

Born in Dominica in 1890, she died in England in 1979, having lived her life mostly in literary obscurity. Much of her writing concerns women who are desperate and in despair, usually after a love affair gone wrong, and usually broke and in very reduced circumstances. Rhys never flinches. She stares it all in the eye with her deceptively simple prose, and writes about fear and loneliness and loss of dignity with great searing bravery. This is not about being selectively confessional—and aren't all confessions selective? This is about standing naked before the reader.

Jean Rhys

Jean RhysEvery time I read this passage from Good Morning, Midnight, I wonder if I will ever have the guts to write like her, with such cold-eyed candor. The heroine, down and out, is thinking about her situation:

“On the contrary, it’s when I am quite sane like this, when I have a couple of extra drinks and am quite sane, that I realize how lucky I am. Saved, rescued, fished-up, half-drowned, out of the deep, dark river, dry clothes, hair shampooed and set. Nobody would know I had ever been in it. Except, of course, that there always remains something. Yes, there always remains something….Never mind, here I am, sane and dry, with my place to hide in. What more do I want?...I’m a bit of an automaton, but sane, surely—dry, cold and sane. Now I have forgotten about dark streets, dark rivers, the pain, the struggle and the drowning….Mind you, I’m not talking about the struggle when you are strong and a good swimmer and there are willing and eager friends on the bank waiting to pull you out at the first sign of distress. I mean the real thing. You jump in with no willing and eager friends around, and when you sink you sink to the accompaniment of loud laughter.”

In later life, when fame and honors were bestowed, she said, simply, "It has come too late."

But there are the books.

July 1, 2022

Living in Winesburg

Garrison Keillor does not like Sherwood Anderson.

Or, rather, he doesn’t like Winesburg, Ohio, which was written by Anderson. He once said the book “is pretty dreadful, and it inspired a whole lot of bad books about sensitive adolescent males needing to flee the philistines in their hometowns.”

I’ve been entertained by Garrison and his A Prairie Home Companion many times over. I’m grateful for the wry and original shows he put on, week after week, year after year.

However, I think he’s wrong about that book.

Winesburg, Ohio, in case you haven’t read it, is a series of linked short stories about life in a small town in Ohio with a recurring character, a young man named George Willard, a stand-in for Anderson. It was published in 1919.

You can make a case for Garrison’s point about the book. Sometimes the writing is naive and simplistic. But his comment is a bit suspect when you consider that his show’s humor seems right out of the small town worries, insecurities and eccentricities that populate Winesburg.

Beyond that, though, is something true embodied in the book and, most dramatically, in one of the stories, “Adventure.” The story is about a lonely woman, in a small town, whose hopes are dashed. A woman whose story, save for Anderson, would be swallowed by much bigger stories that vie, always, for our attention. These are the intimate, intense tragedies in life that everyone knows about and many of us have experienced. Anderson casts his eye on them knowingly and with concern.

“Adventure” is about Alice Hindman who, at sixteen, falls in love with a boy named Ned Currie. She, “betrayed by her desire to have something beautiful come into her rather narrow life,” sleeps with Ned. She imagines they will get married and move away from Winesburg and live happily together. Ned moves to Cleveland without her, then to Chicago, promising, in letters to Alice, he will send for her soon. He never does. His letters become less frequent, and, eventually, stop.

Alice, however, never loses hope. She rejects all offers from other men. She holds onto the belief that Ned will send for her. As the years go on, her hope turns into delusion. Her thinking veers from reality. She no longer thinks about Ned but holds a vague notion of being rescued from her lonely life in this small town.

One night, during a rainstorm, she takes off all her clothes and runs naked into the street. “She thought,” Anderson writes, “that the rain would have some creative and wonderful effect on her body. Not for years had she felt so full of youth and courage. She wanted to leap and run, to cry out, to find some other lonely human and embrace him.”

Suddenly, she realizes what she’s done. Horrified, falling to the ground, not daring to stand up, she crawls back to her house.

Here, I want to ask Garrison to have a close look at this woman, at her life and what she’s come to. I want to ask him if he knows anyone like Alice who has kept the agony of being alone inside her for years and who has reached the point that Alice has reached and, in her bed at night, as Anderson describes it, “turning her face to the wall, began trying to force herself to face bravely the fact that many people must live and die alone, even in Winesburg.”

I can’t speak for you, Garrison, but I know I’ve turned my face to the wall in tears more than once.

June 25, 2022

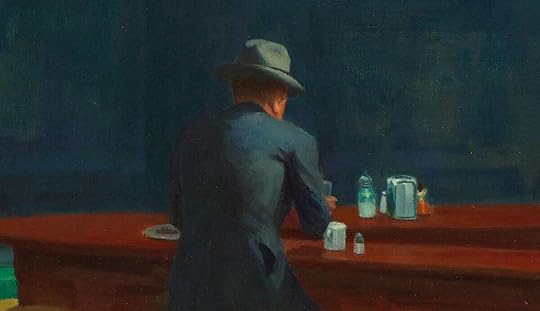

Late night at the bar

It was late and everyone had left the bar except me. I was sitting at a table near the window. It was snowing, and I liked to watch the falling snowflakes play against the streetlights. The view of the snow was good, and it was a pleasant way to pass the time. I liked this bar, because it was clean and because the lighting was soft and didn’t hurt my eyes. I felt comfortable there. I came almost every night to sit and drink by myself. I’d been drinking brandy. I was a little drunk, but I wasn’t showing it. I didn’t make any scenes, just sat there, enjoying the snow falling slowly. It was a little past midnight, near closing time. I wasn’t ready to leave, though. I didn’t want to go home to my empty apartment. It would take me a long time to fall asleep, and so I would be stuck with my thoughts and memories. I would be alone with my aloneness. That’s harder when you get old.

The waiter came up to me.

“It’s time to go home, pop,” he said. “We’re closing.”

“Can I have one more?” I asked. That’s all I wanted. Just one more. To help me sleep when I got home.

“Afraid not.” He looked at his watch.

“But I’m a good customer,” I said. “You know that. I never make any trouble. I just want to sit a little bit longer.”

“Go home, pop,” he said. “I don’t want you to slip and fall on your way home.”

“Just one more,” I said.

“No can do,” the waiter said.

I feared the nighttime. That’s when being alone stalked me. It grabbed me by the throat.

The owner, behind the bar, was at the till, counting out. He was a lot older than my waiter, and he usually had a kind word for me.

“Let him stay until we leave,” the owner said. “Give him one more.”

The waiter went over to the owner, and they proceeded to have a conversation I couldn’t hear. I was grateful for the extra time before I had to leave and go back to my dark apartment. I couldn’t afford to leave the lights on, so when I went home, I was confronted by dark. How dispiriting that is. It always hits me like a slap in the face, opening the door to the dark apartment. It’s a little thing, but it always gets to me.

I put myself directly inside Ernest Hemingway’s short story, “A Clean, Well-lighted Place,” because sooner or later something like this will happen to me. I will be somewhere, sometime, when I’ll want to stay until, and even beyond, closing time. Because it will help assuage the loneliness in my old age. I’m 76. I have no wife to come home to. Just to be among people helps so much. Maybe it will be a bar. Maybe it will be a restaurant. It might even be a store. And if it isn’t a matter of staying late somewhere, it will be another situation where it will be a matter of me being treated decently. At a supermarket, convenience store, car repair shop, department store, pharmacy. Where, being old, people can sense my defenselessness. They can, if they wish, ignore me, take advantage of my slowness, my inability to locate things, my inability to articulate what exactly I want.

“An old man is a nasty thing,” one of the waiters in the Hemingway short story says.

He’s not alone in his opinion.

“Not always,” says the older waiter.

Hemingway’s story, on the surface so dark and cynical, always makes me feel hopeful. The story is about dignity. Dignity is a concept that is most always in the hands of the giver. It is bestowed. A few people have a dignity to them that can’t be taken away, that is strong and sure and goes beyond social status. But for many of us, dignity can be stripped away quickly, because it so often relies on the giver’s unspoken acknowledgement that the receiver merits it—or that any human merits it. Thus it is the most delicate of graces, and as you get older it can become threatened and withheld. Anyone can withhold it at any time for any reason, and the older you are, the more frequent this seems to happen or can happen. With no dignity bestowed upon you, others feel free to heap scorn upon you.

Being old puts you more and more in the hands of others. You need help doing things. Others have to do them for you. But none is so powerful as the simple idea that you retain a certain dignity that is acknowledged, that is sacred. Too often, that is not the case.

I hope I don’t do anything not to deserve the bestowing of dignity. I hope I’m not petulant, disheveled, sloppy. Then I will have less sympathy for me and for people not granting me that sense of dignity. Our father who art in nada, please don’t let me be one of those old men who bring sourness into any room they enter. Who sits alone at a table in a café and looks sullen, unhappy and bitter. Who complains to the waitress about everything. Who you don’t want to look at because their face will taint your own joy. Who doesn’t understand the gift they’ve been given, of life. I pray that I don’t become that person.

Hemingway’s story gives me hope because it tells me there are people out there who will be looking out for me. Who won’t take advantage of the helplessness of my being old, especially when I’m in deep old age. Who will treat me decently. There will be those who won’t, of course. They’ll be the ones to ask me to leave.

“An old man is a nasty thing,” the waiter says.

“Not always,” says the older waiter.

I just have to find the right bar. The one that is a clean, well-lighted place owned by someone who understands that some of us, as we grow old, need a place to go. To stay just a bit longer before they have to go home.

June 21, 2022

The girl in the blue dress

On a trip to Vienna as a young man. I walked into its huge art museum, the Kunsthistorisches, not having a clue. I knew next to nothing about art.

When I walked into one of the galleries, I was met by a series of paintings of a girl. A girl in huge, widely-spread dresses. The dresses looked like they must have taken years to make. And probably a day to get into. But they were the most beautiful things I’d ever seen, these dresses. The face of the girl who wore them wanted to talk to me. Who was this painter?

The painter was Diego Velázquez. The subject was Margarita Teresa, daughter of Philip IV of Spain. She lived, I learned later, in the 17th century. I didn’t care about that then. I just knew deep within me that this painting and probably many others would, by its truth and its power, hold me, delight me and teach me. That made me delirious.

June 10, 2022

The longevity of shame

More bad news? We don’t need it, do we?

Abuse, though. That always needs to see the cleansing light of day.

I wrote an essay about a football coach at the boarding school I attended many years ago who used his power to, literally, try to get into my young pants. He nearly succeeded. I summoned something from somewhere to stop him.

The school fired the coach, but not—at least publicly—for abusing students. Plural, yes, because in fact I didn’t report the coach. Someone else did.

So why write about this 60 years on?

For the same reason anyone who has been abused discloses it. Because it directs a spotlight on someone who has tried to fondle, blow, fuck or stroke them when they were too alone, when they were powerless to stop it, or felt they were.

You have no idea, if you have not experienced this, how jealous shame is. How it doesn’t want you to share. How it wants all the humiliation, remorse and ugliness to be yours and yours alone. And how long its life is. Shame may be the longest-lived emotion there is. And it never loses its grip. Unless you expose its source, and that, for some, is a mighty act of courage.

Let me show you something.

I sent my essay to the boarding school I attended, and they were shocked—shocked!—to learn this (might have!) happened. They started an independent investigation that has been going on for months and that I hope is concluded sooner than later. One of my main questions is: did the school cover this up? You can probably guess my hunch.

But as to my earlier point about the longevity of shame. Some months after I published my essay, I received an e-mail from someone I didn’t know. He found my e-mail address on my website. He wrote to thank me for writing that essay. Because he had been abused by the same man when he was a boy. This in part is what he wrote me:

“I was struck by the fact that your reaction to that experience was so much like mine. Was it a dream? Did I do something to cause this? This memory has haunted me for decades.”