Richard Goodman's Blog, page 16

December 3, 2022

Dean Kostos

I read that Dean Kostos died a few weeks ago. He was a poet and memoirist, exceedingly sensitive and humane.

I never met him. I did know him, though, briefly. I worked with him by phone and e-mail on his memoir, some thirteen or fourteen years ago. The poet Molly Peacock put us together. I write memoir, and she thought I might be able to help him with his project. His memoir is remarkable, but I’m afraid I didn’t contribute that much. I did value our time together, and it was a privilege to work on his book, called The Boy Who Listened to Paintings, which is agonizing, full of pain and hurt. His account of being bullied at school is the most visceral, the most harrowing I’ve ever read. If you want to know what Tennessee Williams meant by the sin of “deliberate cruelty,” read “The Plan,” Chapter 9, of his memoir.

But the joke is on those sadists. Dean Kostos grew up to be a fine, award-winning poet. He said this about poetry in an interview, “For me, poetry is using words to say what words can’t say.” You can read, and listen to Dean Kostos read from his work, here.

There will be a memorial reading of his poems on December 17 at 4pm via Zoom. A number of poets and writers, including Molly Peacock, will read from Dean’s work.

He was just 68 when he died from a heart attack.

November 30, 2022

Louisiana Dirt

Photo by Gaywynn Menard.

Photo by Gaywynn Menard. This is a photograph of me. I’m in Scott, Louisiana, near Lafayette. To be precise, I’m in Ossun, an unincorporated community of 2,144, north of Scott. Even more precise, I’m in front of the house I’m living in with my girlfriend, which is on a sparsely populated country road in that unincorporated community. Our next door neighbor is a long-haul trucker. Across the road lives a mysterious man who moved here only recently and has since installed a large iron fence that keeps out we’re not sure what. Or in, possibly. He lives with his mother who we never see.

What am I doing? It rains a lot in this part of Louisiana. At times, relentlessly. The land—thick, clayey—does not absorb the water well. It can take days before the standing water is finally absorbed. What you’re seeing here is me on our front lawn during a rain we had a few days ago. I’m trying to connect the various flooded areas, Panama Canal-like, so the water can flow to the street. Or, actually, to the ditch near the street where water collects.

I’ve never done this before. Even if I had, it would be tricky. How do you establish a continual grade by sight that starts at the house and descends gradually, foot by foot, for maybe 200 feet, so that the water runs on a downward incline freely to the street? At this point in the photo, I’m simply trying to connect the two major bodies of water by cutting an isthmus. If it works, it will be beneficial. The lawn will drain a lot sooner.

Closeup: just about to (hopefully) connect the Atlantic with the Pacific. Or maybe it’s the other way around.

Closeup: just about to (hopefully) connect the Atlantic with the Pacific. Or maybe it’s the other way around.The digging is hard. I’m not used to it. As I said, the soil is clayey, and clay is dense and heavy and not easy to dislodge. It’s somewhat easier in the rain, though, because at least the clay is not hardened by the sun, as it normally is. I’m panting, but the rain washing over me makes me feel good, and, hopefully, slightly heroic in my girlfriend’s eyes. Or maybe the dog’s. I wouldn’t want to do this 10 hours a day, every day, though, but for an hour or two, I know I’m doing good, honest work. Are we always certain about that? I’m not.

Thrusting a shovel into the earth is primal. It’s just your body, the shovel and the ground. Like rowing a boat, you can’t get more essential than that. The shovel is an ancient, noble tool that allows you to feel an intimate connection with the earth. The only contact with the soil more intimate is with your hands. No one has made any profound improvements on the design of the shovel. (Straight or rounded blade, take your choice, but that’s it.) Materials, yes, maybe, but concept? No.

Roman shovel, circa 1-3rd century CE. Not that different in design than what you find at Home Depot.

Roman shovel, circa 1-3rd century CE. Not that different in design than what you find at Home Depot. My efforts at connecting the two bodies of water on our lawn to make a navigable canal through our lawn were only moderately successful. The task was beyond me, really. I have so much to learn. I can report, though, that at least some of the water in the little lake nearest to the road did, in fact, drain into the ditch. Still, my work had simplicity and purpose.

I came back out of the rain. My arms were tired, my chest was heaving. I was wet, sweaty, spent and happy.

November 24, 2022

Thankful

I’m thankful for so many things.

First, for my daughter. The best thing to ever happen to me is being the father of this beautiful, radiant young woman.

I’m thankful for my good health.

I’m thankful for light; for the English language; for olive oil; Thoreau; letters, both writing and receiving; pencils; walking; legal pads; travel; reading; Hemingway; museums; laughing; storms; Paris; writing; birds; learning; the ocean.

For funny women, laughing women; the French language; gardening; poetry; outdoor showers; Maine; surfcasting; Willa Cather; good food; Flaubert’s letters; the moon; The Great Gatsby; Southern food/soul food.

For my Smith-Corona Galaxie II manual typewriter; the female body; cooking; my first apartment in New York City on Tenth Street; research; rock climbing; music; M.F.K. Fisher; Giotto; books; van Gogh; French bookstores; the smell of a Parisian morning; the sound of rain; dogs; Henry James’ critical writings; New York City; driving and walking down country roads; Isak Dinesen; fall, winter, spring, summer: the four seasons; master/student relationships; opera; the light in Provence.

For salt air; Ralph Ellison; Velázquez; Verdi; a good baguette; my sister; snow falling down; road trips; going to sleep when I’m exhausted; tea; kayaking; Van Morrison; the Frick Museum; the Italian language; my bicycle; Michelin maps; François Truffaut; tomatoes; my daughter’s laugh; honeysuckle; tall, slim pine trees; New Directions paperbacks; Tennessee Williams.

For moist earth; women’s backs; old docks; going barefoot; etymology; women in summer dresses; James Baldwin; friendship; biscuits; work; identifying plants and trees; New Orleans; porches; the songs of birds; Balzac; garlic; Cole Porter; breasts; women’s rich, lavish hair; West Fourth Street in New York City; Paul Lynde; libraries; the smell of hay; my daughter’s gorgeous smile; sweat; the Seine; Rome; the stillness of early morning; Pablo Neruda’s poetry.

For surfing; cross-country skiing; overcoming fear; deep, pristine snow; water; wood, the smell and feel of it; herons and egrets; trains; Deb Attoinese; my struggle to make my book, French Dirt, the best book I could write; for peeing outside; a simple desk, a simple chair; my brother; the rejuvenation sleep provides; Jean Rhys; coming home to someone you love; wetlands.

For a cast iron skillet; Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers; a good dictionary; lovemaking; Big Joe Turner; Evelyn Waugh; the Cevennes; rock ‘n’ roll; full lips; seeing my daughter born, holding her for the first time; Joseph Conrad; Marcel Pagnol; Chester, my dog, RIP; my memory; pecan pie; Ms. Booth, Ms. Benson, Ms. Shugrue, Ms. Carley, all the teachers who were so kind to my daughter.

For Langston Hughes; Greenwich Village; warblers; kindness; pastrami; watching my daughter play basketball and softball; bookstores; belly laughs; breathing; Lucinda Williams; the smell of suntan lotion at the beach; dusk; coffee; Ray Charles; brilliant sunsets; Elizabeth Bishop; Central Park; Wellfleet oysters; stretching; friends’ voices; making up stories for my daughter when she was young; affection; holding hands with a woman you love; the release of crying; John Lennon; truth.

And, especially this Thanksgiving, for Gaywynn. For us.

November 19, 2022

The thrill of compost

One of the most delightful things about compost is that I can turn a bad meal into gold. Black gold, actually. That’s what compost is, black, sticky, sweet-smelling gold. It’s alchemy.

Anything that you’ve kept too long, overcooked, let wilt, has mold, looks wizened, etc., can be put into the compost bin or pile and will eventually be given new life. Exceptions, of course: no meat or dairy products for various reasons, not the least of which is rummaging animals with acute senses of smell and dexterous paws. But much of what you eat can be turned, like magic, into precious compost. Add dry leaves and grass from time to time for needed carbon and nitrogen. They’re free!

My girlfriend is disgusted by compost. Well, to be precise, she doesn’t like the various larvae or wormy creatures that make their way through and around the decaying and metamorphizing mass. “They becomes flies!” she said as I held up a portion of our compost for her to gaze at, twisty things moving within. “Get that away from me!” I, on the other hand, stick my nose right next to it, practically kissing the larvae. “You beautiful things, you! Work your magic!” I croon.

Gold, I tell you! Pure gold!

Gold, I tell you! Pure gold!Compost, “improves nutrient retention and delivers needed food for the plants in the form of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium,” according to the US Composting Council. Yes, there is a US Composting Council. I like that they call themselves a council. Composting also provides a sense that you’re doing something for our wobbly planet by not increasing the landfill, even on this minuscule scale.

The first compost I “made,” I used in a raised bed garden my girlfriend and I assembled. I bought quite a few bags of soil and then combined it with the first batch of our home-concocted compost. I should have marked it like wine: “Barrel #1, Fall, 2022,” or something like that. Actually, come to think of it, I’m sure different compost produced at different times with different ingredients at different geographical locations looks and smells different with subtle scent distinctions.

My compost here in southern Louisiana has an appealing bouquet with “traces of peach and coffee, enhanced by hints of blueberries and celery, with an after-scent of young russet potato skins, earl gray tea bags and live oak leaves.” I sometimes open the composter just to imbibe the scent of this earthy stuff, much like uncorking a vintage Bordeaux for its perfume. Only it’s a lot cheaper.

In fact, maybe I could become a compost sommelier.

“Can you recommend something to support our leeks and mustard greens?”

“Of course. Since you live in the Midwest, I would go with the Chateau Topeka, ‘01. It’s a limited vintage with strong hints of young carrot peels, shredded red cabbage, organic egg shells, zucchini ends and—this is quite rare—matzah.”

I think I have the nose for it.

We planted winter vegetables in our raised garden bed, and they’re doing very well. In fact, there was a brief moment when we were planting that I thought: I wish I could be planted in this dark, delicious mix. It looks so damn good.

November 14, 2022

Naked and unafraid

Last night, I saw a friend disrobe in public.

It was at the Oak Street Brewery in New Orleans. The place hosted an open mic night for comedians. My friend is a documentary filmmaker and a professor. He decided recently to try his hand at stand-up comedy. He’d done some improv, and this seemed the next logical step. He was taking a chance.

So there we were. At 7pm, he was waiting with six or seven other hopefuls to go on. The place was large, the crowd was small. At one point, there were more comedians than audience members—or so it seemed. Not the best atmosphere.

The comedians who went on before my friend, and afterwards, had varying degrees of success.

Sample: tall shy-looking guy, said, “I was walking on the street the other day and a guy came up to me and said, ‘You suck!’ At first, I was outraged. Then I thought, “How does he know?”

Another guy, short with spiky dyed hair. “I’m in therapy. I have commitment issues. I told this to my therapist, but I don’t think she heard me. In the waiting room, I saw a couple leaving her office before I went in. I told her, ‘You’re seeing other people!’”

Funny? I thought so. The scant audience didn’t agree. There was silence. Silence you could feel, like wind. The kind of silence that makes you tremble a bit. When the comedian is confronted with it, there is not a shred of doubt about what it is. There is a kind of purity to it. There is no ambiguity in silence.

You’re on next!

You’re on next!I suggested beforehand that my friend get up to the mic and actually take off his clothes. “Doing standup is like being naked in front of the world,” I noted. “Why not take that cliché and make it real?” He declined. However, when you go to see an open mic evening, watch comedians confronted by outer space-like silence, you realize that it might actually be easier to be literally naked.

My friend’s name was called. Up he went. He took the mic and told his jokes. The reception was, as they say, polite. I really thought some of his stuff was strong. Original. Clever. He had one joke about being allergic to a spelling bee that I thought was very funny.

It’s a brave thing to stand up in front of strangers to try to make them laugh with jokes of your own making. It’s the difference between exposing yourself, who you are, and not. Because what is more vulnerable than offering something you’ve created to the world and saying, this is what I did. Like it? This is who I am? Like me?

Afterwards, when we went outside to talk about his set, I told my friend I admired his courage. I meant it. I also told him I might try stand-up myself. Why? Because it would be great to get some laughs from strangers, I think. What a rush! But mostly because there is a world of difference between watching someone up there with a mic in their hand like my friend trying to make people laugh and you sitting there safe, dry, warm and unscathed in your seat.

So, here’s a joke I’ve been working on. Ready? “My dad’s Jewish. So on Rosh Hashana, I take a half a day off.”

Ok, thank you! No, really! More? Ok, here’s another. “My bank account got hacked the other day. It’s so meager, the hacker actually left me money.”

I’m here all night.

November 8, 2022

The pussycat in the restaurant

It was in Greenwich Village, on Hudson Street. It was a small, intimate restaurant, almost a square in shape, with a tiny bar in back and square tables that seated two, four and six people. It served Italian food. It wasn’t expensive, and the food was good, and this attracted a lot of the people in the neighborhood, including me. I lived on Abingdon Square, across the street. It was an affordable place to meet someone for lunch or dinner, and that was always a good find, since many of my friends were trying to be writers, painters or musicians and never had much money. I don’t remember the name of the place. This takes place in 1981 or 1982. The exact date doesn’t matter. I do know that it was a warm spring day, and I was there for lunch with a friend who lived in the same pre-war apartment building as I did.

He was sitting at the table directly in front of me, his widespread back toward me. It was one of those slow recognitions, the kind that ease into your mind over a period of minutes as the elements come together little by little in that part of your brain that isn’t occupied by your food, the person across from you, and a series of several self-centered reflections that dart before your inner eye. It was his head that brought it all into focus—massive, slightly oblong and bald, an older man. It was the head of a giant out of a fairy tale. I recognized that head, even from behind. I knew who he was.

It was James Beard.

It made sense. He lived, as I knew, because I was part of the neighborhood, on West 12th Street. He would have been nearly eighty. I knew that his brownstone was also a cooking school. After his death, it became the home of the James Beard Foundation, which has since celebrated and fostered American cooking and its chefs. The point is that I knew who he was. I confirmed his identity later when I left and could catch a glimpse of his face.

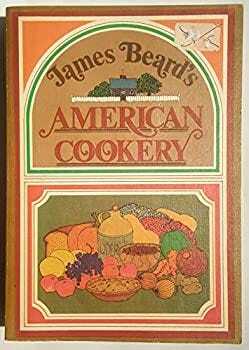

He wrote over thirty cookbooks, and I’ve had a few through the years, but the one I've had for forty years and always return to with delight is James Beard's American Cookery. The pages are mottled and grease-stained, the true signs of a cookbook that has been rigorously and lovingly consulted many times under fire. Some of it is dated—he has over thirty entries for "Candy," for example. But most of it isn't, and, more important, none of the writing is. I have yet to find a writer who knows more about American food and its history than James Beard.

Naturally I was happy to see one of my culinary and literary heroes seated at the next table, even if I couldn’t see his face. Well, I knew one thing. If James Beard was eating here, the food had to be good.

Then I noticed something. I saw, peeking out from the considerable waistband of his trousers, a white plastic edge. It was frilled. My heart sank.

I was about thirty-five then. I had no real sense of growing old. In other words, I didn’t think this might be me one day. What I did think was: why should this great man who wrote so elegantly and knowingly about food and who has given so much pleasure to so many people, be reduced to wearing a diaper?

There is so often no correlation between what a person contributes to our world and how they end up passing their final years.

Then the voice intruded. I had blocked it, and other voices in the restaurant, from my conversation with my friend up until then. The voice was soft and easy, but there was a sense of struggle in it, traces of tiredness and of age. I began to listen to the conversation. All I could catch was a snippet. Beard said,

“Tom, they say we’re tough, but we’re not, are we? We’re both pussycats, aren’t we? I’m a pussycat.”

There he was, James Beard, among us. If it meant wearing an adult undergarment, so be it. He was still in the game. If it comes to that for me, I hope I get over it. And stay in the game. James Beard was here, enjoying the day, out and about, talking with friends, eating good food, convivial and lucid, alive and well.

The lion in the restaurant

It was in Greenwich Village, on Hudson Street. It was a small, intimate restaurant, almost a square in shape, with a tiny bar in back and square tables that seated two, four and six people. It served Italian food. It wasn’t expensive, and the food was good, and so, naturally, this attracted a lot of the people in the neighborhood, including me. I lived on Abingdon Square, across the street. It was an affordable place to meet someone for lunch or dinner, and that was always a good find, since many of my friends were trying to be writers, painters or musicians and never had much money. I don’t remember the name of the place. This takes place in 1981 or 1982. The exact date doesn’t matter. I do know that it was a warm spring day, and I was there for lunch with a female friend who lived in the same pre-war apartment building as I did.

He was sitting at the table directly in front of me, his widespread back toward me. It was one of those slow recognitions, the kind that ease into your mind over a period of minutes as the elements come together little by little in that part of your brain that isn’t occupied by your food, the person across from you, and a series of several self-centered reflections that dart before your inner eye. It was his head that brought it all into focus—massive, slightly oblong and bald, an older man. It was the head of a giant. I recognized that head, even from behind. I knew who he was.

It was James Beard.

It made sense. He lived, as I knew, because I was part of the neighborhood, on West 12th Street. He would have been nearly eighty. I knew that his brownstone was also a cooking school. After his death, it became the home of the James Beard Foundation, which has since celebrated and fostered American cooking and its chefs. The point is that I knew who he was.

He wrote over thirty cookbooks, and I’ve had a few through the years, but the one I've had for forty years and always return to with delight is James Beard's American Cookery. The pages are mottled and grease-stained, the true signs of a cookbook that has been rigorously and lovingly consulted many times under fire. Some of it is dated—he has over thirty entries for "Candy," for example. But most of it isn't, and, more important, none of the writing is. I have yet to find a writer who knows more about American food and its history than James Beard.

Naturally I was happy to see one of my culinary and literary heroes seated at the next table, even if I couldn’t see his face. Well, I knew one thing. If James Beard was eating here, the food had to be good. It wasn’t just me, then. A kind of self-satisfied smugness went through me.

Then the voice intruded. I had blocked it, and other voices in the restaurant, from my conversation with my friend up until then. The voice was soft and easy, but there was a sense of struggle in it, traces of tiredness and of age. I began to listen to the conversation. All I could catch was a snippet. Beard said,

“Tom, they say we’re tough, but we’re not, are we? We’re both pussycats, aren’t we? I’m a pussycat.”

Lion.

October 30, 2022

The great pastrami hunt

I wanted pastrami.

I’d just been in New York City for a week and did not get my taste of pastrami. Or great pastrami, at least. It wasn’t New York’s fault. A friend told me that Barney Greengrass, a heralded delicatessen on the Upper West Side, sold pastrami as well as their famous lox, whitefish, sturgeon and other cured fish. I’d known about Barney Greengrass for years, but never knew it sold pastrami.

It shouldn’t. At least not what I ate. It wasn’t that good.

Normally, I go to Katz’s, Manhattan’s most renowned Jewish deli. (Pastrami was invented by Jews.) They serve real pastrami, beautiful pastrami, savory, melt-in-your-heart pastrami. The drawback? The crowds at Katz’s are like Walmart on Black Friday. You fight for your position at the counter to order. People are not kind. They want their pastrami as much as you do. It can get physical. Jostling, shoving, etc. Come ready for combat.

Katz’s pastrami. Heaven, I’m in heaven.

Katz’s pastrami. Heaven, I’m in heaven.This time, I wasn’t inclined to struggle for my pastrami at Katz’s. So I left New York without my fix of the real thing.

I returned to my home near Lafayette, Louisiana, a part of the world that is not generally known for its pastrami—or for its Jews, for that matter. I did some deep research—40 seconds on the Internet—and found there is, indeed, a synagogue in Lafayette. So, there are Jews here! But also in my deep research, I found no Jewish delicatessens. Lafayette Jews, why not? It’s me, Richard. I’m hungry.

However, I did find a place that serves a classic Reuben sandwich. Acadian Superette. Yes, I know, the name didn’t exactly summon a world of men wearing yarmulkes or busy countermen delving out beauty, but where there is Reuben, there is pastrami. I figured if they had pastrami, they might sell it on its own.

The Reuben sandwich from Acadian Superette. Looks ok, right?

The Reuben sandwich from Acadian Superette. Looks ok, right?So my girlfriend and I hopped in the car and drove off for a date with destiny.

I think we all know what it’s like to have a food craving. To have a craving that must, repeat must, be satisfied. It can border on the obsessive. It can cross that border, actually. You will hunt down that food, venture out at all hours, drive many miles, to satisfy that craving. I am not speaking of a marijuana-induced craving, but a natural insanity.

So you understand the general principle working here. You may not see why I was so desperate for pastrami. You may never have eaten pastrami. More particularly, you may never have eaten great pastrami. Well, as with any craving, these things are not explainable.

We drove to the Acadian Superette. I was in a state of high anticipation. To think that I might get this longing for pastrami satisfied soon was beyond my wildest dreams. I dismissed the fact that I was in southwest Louisiana. I was salivating in pre-orgasmic joy. My girlfriend looked away.

We arrived. I immediately asked the cheerful woman behind the counter if they sold pastrami by the pound.

“Yes, we have some over there.” She pointed to a refrigerated display case.

Really?

“Is it Jewish pastrami?” I asked her.

She looked slightly bewildered. “Uh, I’m not sure…let me go ask.”

She turned and went to the back of the store. A man emerged soon after. Amiable, ready to inform and answer.

I asked him the same question.

“I’m not sure what you mean,” he said.

“Have you ever been to New York?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, “but I didn’t eat pastrami that time.”

“Well,” I pushed, “is it it made with Cajun spices?” Most meat sold at small markets in this area have a red dusting of spices characteristic of the local cuisine that, to my mind, overwhelm the taste of the actual meat.

“No, we don’t use Cajun spices,” he replied definitively. “I cure it myself. It’s brined.”

That sounded hopeful! This was all on an intellectual level, though. I decided to get to the point.

“Could I have a sample, please?”

“Sure.”

He went to the back of the store and returned with a small paper container. Three small slivers rested there. They had the appearance of pastrami!

“It’s cold,” he said, offering it to me. “Is that all right?”

Not really, but I couldn’t quibble, since he was so gracious to provide the sample, gratis. “That’s fine,” I said.

I took one of the small strips of meat and placed it in my mouth.

No. Alas, no. No! My heart sank.

He looked at me expectantly.

“I’m afraid I’m a pastrami snob,” I said. “This is very good, but I’m finicky when it comes to pastrami.”

He smiled. “I understand.”

I had to put my pastrami obsession in that place we put all unrequited food cravings, somewhere in the back of my mind and belly. A bitter pill. The craving would re-emerge, I knew, and when it did, I might have to satisfy it by driving 2 1/2 hours to New Orleans to Stein’s Deli on Magazine Street. Their pastrami is pretty damn good. Or I could go to Katz’s website and fantasize about ordering their pastrami by mail. $38 per pound, plus shipping, $35. My girlfriend nixed that idea due to budgetary concerns, but I may do it anyway. Don’t show her this.

October 24, 2022

Shame, update

I wrote a post in June about shame. About its longevity. The origin of my shame was a football coach at the boarding school I attended sixty years ago who abused me.

I wrote about that and published what I wrote in River Teeth, a literary journal, in the spring of 2021. (If anyone is interested in reading the piece, I’ll be glad to send it to you. Just leave me a note.) I sent the published account to Cranbrook, in Michigan, the school in question.

The head of school read the piece and wanted to talk. So we did, by telephone. Thus followed a lesson in caution on her part. However, to her credit, she then hired an outside firm to investigate.

Aside from finding out the extent of this man’s perfidy, one of the main questions I want answered, I told her, is: did the school cover this up? At the time, the football coach was dismissed for what the then head of school described as “philosophical differences”—or words to that effect. If the school covered up what really happened, isn’t a crime involved? Weren’t you required by law to report sexual abuse of a boy, or boys, by an adult to the police, even back then? I wonder if the parents were even informed. Because, if you were like me, you were too ashamed to tell anyone, and so your parents never knew.

The investigation launched by Cranbrook began in 2021. It’s been going on now for well over a year and, as far as I can tell, has no immediate finishing date. I have contacted the school on several occasions asking them about the investigation’s progress. I wrote the investigator herself in August, fourteen months on, and reminded her that at least one of my classmates has died in the last year and that, given our ages, most likely more will. We’re all in our late seventies. Those who were affected by this man deserve justice, I told her, before it’s too late.

Her response:

“This acknowledges receipt of your email and your concerns are noted.”

In a letter to the Cranbrook community—and as reported by local media—the head of school wrote:

“[The investigator] recently informed us that her investigation, while ongoing, has identified additional alumni from this same time period reporting sexual impropriety by this same now-deceased former faculty member.”

The head of school’s point, repeated by the investigator, is that they want to conduct this investigation thoroughly and properly. I am all for that, within reason.

It’s sixteen months on. My classmates and I deserve the truth. We don’t have all the time in the world.

October 20, 2022

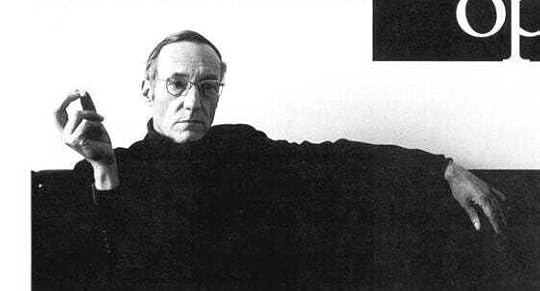

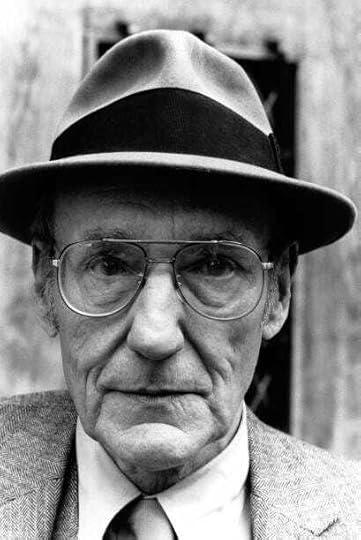

An evening with William Burroughs

I arrived at Burroughs’ London flat off Piccadilly in the early evening. Burroughs opened the door, and I saw a smaller man than I had expected from the photos, with thin grey hair pushed over to cover baldness. He appeared to be in his late fifties, but it was difficult to say exactly. He wore slacks and a turtleneck, both of which were too large for him. We shook hands, and he motioned me in. He seemed shy, even a bit awkward, as if I were perhaps the host and he were the guest.

His apartment was sparse, with plain adequate furniture, and pleasant. He had a living room, bedroom, bathroom and kitchen. All our conversation took place in the small living room. He had only a few books, and these were mostly copies of his own works. A few other authors, including Terry Southern, were represented.

A “young man” named Johnny was there. He was English and wore tight slacks and a turtleneck. He was friendly, obviously not a student of the arts. He served the drinks, lit the cigarettes, emptied the ashtrays, and for the most part was content to stand and not say anything. Occasionally, he would add a Goofy-like affirmation to something. He left, with a pound note from Burroughs, about an hour after I arrived.

Burroughs sat on a stool in the center of the living room with a cigarette almost always pressed to his lips or dangling from his hand. Ashtrays seemed to grow hills of butts quickly, and quite soon the room was very smoky. Though Burroughs was silent to begin with, almost forcing me to prod him, he answered all my questions politely and sometimes anecdotally. He carries with him a flavor of formality. He speaks with an inflected drone, and he did not always look at me when he spoke. I began by asking him what his latest project was.

“I’m writing a novel. It’s over there.” He pointed to the desk next to the window.

“I just got back from New York. I flew over there with the film script of Naked Lunch. A producer said he was interested: I think he does ‘The Dating Game’ or some quiz show. So, Terry Southern and I flew out to LA at his expense. When we arrived, this big black shiny Rolls-Royce met us at the airport, whisked us on into town. Well, it turned out he wasn’t interested. He was worried about all the sex and violence. He said we’d have to cut out all the sex scenes and a lot of the scenes with violence. But what’s Naked Lunch without sex and violence?” He spread his arms to indicate “nothing.’’

“Terry and I did some cutting, but he still wasn’t satisfied, so we gave it up. When we went to leave the Rolls had shrunk considerably, down to some kind of mini. I said to Terry, ‘We’d better get out of here fast before he decides not to pay the hotel bill.’”

Did he have anyone specific in mind for parts in the movie version of Naked Lunch?

“Yes. We wanted James Taylor, Mick Jagger, or Dennis Hopper for Lee. Taylor and Jagger said no, and Hopper was all set to go, but it was dropped since there was no financing. We wanted Groucho Marx for Dr. Benway, but he wouldn’t hear of it.

William Burroughs, at the time of my visit

William Burroughs, at the time of my visit“It’s terribly difficult to get backing for a film. Distribution’s a problem, too. Most of the time you end up not making any money on the damned thing, so you have to get everything on that first sale. After that, baby, it’s gone. I’ve got several other film scripts here. Some just in idea form and some full shooting-scripts. I did one on the life of Dutch Schultz. But I’ll never sell that. Too expensive to produce. Too many scenes.” What did he think of the movie A Clockwork Orange, very popular in London at the time? He had praised the book.

‘‘I thought the movie fell apart exactly where the book did. In the middle. Everything goes along quite well, then you come to the middle section. During that whole prison sequence I kept wondering what the hell Kubrick was doing.

“Did you see The Godfather? I liked that. Very good. But Pacino stole the show. That scene when he comes out of the john with the gun hidden, and the guy thinks something is wrong for that split second, but he’s too late. Then bam! two slugs in the belly.

“I wanted to see the film, because an old friend of mine’s in it. One of my former customers. That was in New York, years ago. He was a member of the Mafia then, and they didn’t like the fact that he was on junk. They said he was a disgrace to the family. So, they told him either get off junk or else. Apparently, this frightened him into his senses, and he quit. I saw him recently, and he told me’ ‘Baby, I don’t need junk. I don’t want it.’ I thought he did pretty well in the film.”

He picked up a thick volume and handed it to me.

“Here. Take a look at this,” he said.

It was the full report of the President’s Commission on Pornography, replete with color photographs. It had been given to him by Terry Southern.

“When I was in New York, I saw a lot of pornographic films, about twenty of them, mostly gay films. All around the Times Square area. And very good quality, with close-ups both oral and genital. Good-looking models, too. The fact is, if you can’t perform, you just don’t make it. You go in someplace. and immediately you’re in front of the camera; if you can’t do it. baby, they can get somebody else.

“Those animal pictures are disgusting. aren’t they?” he said in reference to some of the harder hard-core photographs.

“I’m going back to New York in a few months. They’ve asked me to be a judge in the Erotic Film Festival. I’ll be there for about a week. But I don’t like New York. Can’t stand it. Can’t get out of there quick enough.”

Now that the subject of sex was about, I asked Burroughs what he thought about homosexuality. I thought I had discerned a conflict in his writings: while it is obvious that he is much more interested in homosexuality than heterosexuality, he often satirizes his homosexual characters and their behavior, even to the point of overtly putting them down. There is one long sequence in Naked Lunch in which a straight boy is mocked and mentally tortured into making homosexual admissions by a mad doctor. Why? Did he have a negative view of homosexuality...

“Nooo.”

But what about the satire?

“Well, I say so when they get a little out of hand. But that’s not my view. No, not at all.”

“We know that the brain can be electronically made to produce any response,” he said in reference to the Naked Lunch sequence I had mentioned.

I asked him about Jack Kerouac. Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg had been “students” of Burroughs’ back in the early Beat days. Did he miss Kerouac?

“Oh, Jack, Jack. Well, I hadn’t seen him for years. I saw him briefly in New York in 1968 after I had returned from Chicago (Burroughs was covering the Democratic National Convention for Esquire) and was staying in the Hotel Delmonico writing the article for Esquire. He came up to my hotel room and brought his three Greek brothers-in-law with him. They ran up a two-hundred-dollar liquor bill. Esquire didn’t want to pay the bill, but I told them they had to, and they ended up paying.

“They asked Jack to debate William Buckley on television. He was champing at the bit. But I said to him, ‘You can’t go on there. You’ll be cut to ribbons.’ They wanted me to go along as a spectator, but I wouldn’t have any part of it. So, Jack went on, and it was a farce. That was the last time I saw him.”

What about Jean Genet in Chicago? Genet had also covered the Convention for Esquire. Did Burroughs have much of a chance to talk with him?

“Oh, yes. Quite a bit. He doesn’t speak a word of English, and my French is very limited. But we got on somehow.”

I had read that Genet had escaped a beating from the Chicago police by simply, well, shrugging his way out of the situation.

‘‘Well,’’ said Burroughs, “what happened was that he was being chased by a cop, and he turned around and shrugged as the cop was about to hit him with his club, and the cop veered away. But more cops were coming, so Genet took refuge in the nearest apartment building. Then he just knocked on the first door he came to. It turned out to be a student’s apartment. This guy with a beard opened the door. and Genet said. ‘Je suis Monsieur Genet.’ And the guy said. ‘Oh, great! Come on in. I’m doing my thesis on you.”

What, if anything, did Burroughs miss most about America?

“The food. It’s impossible to get a decent meal here. I miss Horn and Hardarts. [An automat.] For about a buck-fifty you can get a really decent meal. I could eat there every day of the week.”

Why was he living in London?

WSB

WSB“Taxes, Baby. I get off much better here than I would in the States. It’s purely monetary. Oh, London; well, I don’t much care for London itself. No, I could just as well live somewhere else. The services here are terrible. If I want an electrician or a plumber, I have to practically start a war before I get him. Awful. The trouble is that they don’t pay those people a damn thing.’’

About seven o’clock, a young friend of Burroughs’ named Miles dropped by. He immediately made himself at home, lying on the couch to Burroughs’ left. Miles is a collector of Burroughs’ work. He is presently, at Burroughs’ request and under his supervision, putting together “The Archives.’’ This is a collection of Burroughs’ books, articles and letters, along with pieces published about him. The collection will eventually be sold to the highest bidder. Miles, quite affable, often added to Burroughs’ conversation, addressing Burroughs as ‘‘William.’’ Miles showed B. what he had done that day on The Archives. B. examined the small file Miles handed him and pulled out a few items.

‘‘I don’t think we’ll include the laundry slips,’’ he said as he eliminated an item.

When I heard that his personal letters were going into The Archives, I told Burroughs that I hoped he would soon publish more of his correspondence. ( B., I found out later, makes a carbon copy of every letter he writes, He does plan to publish more of his correspondence.) I told him that I liked The Yage Letters very much (a book consisting of an exchange of letters between Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg) but that I didn’t like Allen Ginsberg’s contribution as much. I thought it was a bit self-indulgent.

“Oh, well,” he said. ‘‘Allen has this idea that the whole world is love. Everyone is everyone’s brother, that kind of thing. He’s always felt that way. But I have a different view. I think there are sinister people about, trying to do you harm.’’

I thought of Burroughs wandering through Mexico and Central America in the early fifties. Had he met any Joseph Conrad-type Germans in the jungles?

‘‘Oh, yes. Real Joseph Conrad Germans. One character in a mountain village claimed he had the only existing map to the secret treasure of the Spanish monks. Something like that. He told me all we had to do was to go out and dig it up. It was just waiting for us. He wanted some money, but I didn’t give him anything.”

What about the revolver the character Lee (an early pseudonym for Burroughs himself) carried in Junkie? Did Burroughs himself ever carry a gun?

‘‘Ohhh, yeah. When I was in Mexico City. I used to have this big ol’ .380 automatic. Used to stick it in my pants, right here.’’ He pointed to his stomach-belt area. He was talking like a cowboy now. “I remember one day I went into this pissoir, and I was waitin’ for my turn, when this man comes in—a typical Mexican punk—and he pushes his way in front of me. So, I opened my coat and tapped the handle.’’ Pause. ‘‘He didn’t go into that pissoir ahead of me.’’

I thought better of bringing up the subject of how he accidentally killed his wife playing William Tell with a revolver.

A little later another friend named John dropped by. John had long white hair: he might have been fifty or he might have been forty. He sat down at Burroughs’ right, and he and B. bantered each other about why B. hadn’t called him that day as he had promised. This was well past the time when we had begun drinking Burroughs’ liquor, and B. was loosening up a bit.

‘‘Well, look, Baby, I did,’’ B. said. ‘‘I’ve got the number right here.’’ He got up, walked to his desk, and began searching for the number. ‘‘I called you this afternoon, five o’clock, Baby. But the only person who answered was this Italian waiter. I mean, I’m sure he’s very nice, but he wasn’t you.’’

‘‘Well, I’m sure I gave you the right number, William,’’ John said.

‘‘Baby, It couldn’t have been the right number, because all I could get was this goddam Italian waiter who spoke Italian, and I don’t speak Italian. Now, just wait a minute while I get that piece of paper you gave me with the number on it.’’

After this was finally settled—John had mistakenly given Burroughs his “old’’ number—John proceeded to explain to me that he was the first person ever “cleared” from Scientology. A sort of black belt achievement. He talked about that and reincarnation and his appearances on a television talk show.

‘‘This is not my first life,’’ he said. ‘‘Oh, yes, my last life was very good, very interesting. But it was so good to be able to finally say good-bye, to lay my body down and just give it all up. But I loved working with all those silent film stars. They were wonderful, kind people. When I was on the show, the host asked me. ‘Were you Rudolph Valentino in your last life?’ I wouldn’t say yes, and I wouldn’t say no.’’

He and Burroughs then talked about personal matters for a bit.

About nine o’clock, B. had a little entourage in his apartment. There were murmurs of, “I’m hungry,’’ and, “Let’s get something to eat.’’ Someone suggested a Mexican restaurant in Soho. Everyone agreed, but Burroughs maintained control.

‘‘Ok, now let’s not go into this thing too hastily,’’ he said.

Finally, he had the plan. We all got up to leave, and immediately someone was reaching for Burroughs’ coat, while someone else went for his hat. After one person had helped him put on his coat and another had given him his hat, he turned to me and said with a wry smile, “Around here, I’m known as ‘The Don.’”

We took a cab to Soho. It was a good restaurant and a good Mexican meal, but Burroughs wasn’t talkative. He preferred to sit back easily at the head of the table and listen to the talk of Scientology and reincarnation. I felt it was a waste. I asked him about Norman Mailer.

“I like Norman,” he said slowly and precisely, ‘‘A lot of people say they have trouble with Norman, but I don’t. Get along with him quite well.’’

He seemed distant, so I left him alone.

The check arrived, and Burroughs examined it carefully.

‘‘Ok, boys,’’ he announced, “looks like we’ve run up quite a bill here.”

We paid and strolled out into the street. It was about ten-thirty. Pub closing time, nearly. Although Burroughs hates pubs, he suggested we all go to a gay pub. So, we walked on, Burroughs in command. Most of us had had our share of liquor by then. The talk on the way over was easy.

We arrived at the pub. Burroughs struck up a conversation with a friend of a friend, and I talked with Miles.

“William’s amazing,’’ he said. ‘‘He must do three or four versions of each work. I’d say he only publishes twenty percent of what he actually writes. The other things are mostly first, second and even third drafts. He works very hard. Eight hours a day, I’d say. Often more than that.’’

When we left the pub it turned out that Burroughs was going one way and the rest of us were going another. Burroughs seemed a bit wobbly to me, and I was worried that he might have trouble finding his way home. He was going to walk. He shook my hand warmly.

“Ok, Baby.’’ he said. ‘‘You’ve got my address. Next time you’re in London, look me up.”

He waved and ambled off down the street. We watched him disappear into the blackness of the night. Then we turned away and began walking.

“Will he be all right?” I asked Miles.

“William? Oh, sure. Somehow he always seems to find his way home.”