Richard Goodman's Blog, page 23

April 18, 2020

Here!

Everything becomes not taken for granted.

Breathing, to start. Maybe, like me, you aren't a Buddhist, or especially mindful, and so weren't paying a lot of attention to your breathing. But now perhaps you are. Still breathing. Pretty good deal, isn't it?

Then there's the sky. Wide and gray or blue, or white and blue, it's there. This majestic semicircle. Always changing, providing a new palette. A fresh drama of curiously-shaped clouds that move sometimes, sometimes don't. A sky that can be a wide wash of gray or a clear azure. That can erupt in jagged white bolts followed by jump-inducing thunder. A sky that can send our roots rain.

Let me not forget light. I mean the opposite of darkness. The slow drawing aside of the night's curtain every morning to reveal the sun's emergence. Not much is reliable these days. In fact, is anything reliable? The sun is. I use its steadfastness every day to give me an anchor. Once again, there it is. Climbing upward. Unfaltering.

The senses. W.H. Auden called them "Precious Five." Sight, smell, touch, hearing, taste. What these times have made abundantly clear is that death is real, it's near, it's possible. The place I put death in my daily life before this was somewhere in the remote part of the Outer Banks of my mind. Not anymore. So, seeing things. Smelling things. Tasting things, touching and hearing things. With gratitude.

If this situation has done anything, it's stopped time. Or slowed it down considerably. Forced not to do most everything we used to do, we're left to observe and experience what is directly before us, in every sense.

For those of us who are not sick or struggling, a gift many of us had forgotten.

Breathing, to start. Maybe, like me, you aren't a Buddhist, or especially mindful, and so weren't paying a lot of attention to your breathing. But now perhaps you are. Still breathing. Pretty good deal, isn't it?

Then there's the sky. Wide and gray or blue, or white and blue, it's there. This majestic semicircle. Always changing, providing a new palette. A fresh drama of curiously-shaped clouds that move sometimes, sometimes don't. A sky that can be a wide wash of gray or a clear azure. That can erupt in jagged white bolts followed by jump-inducing thunder. A sky that can send our roots rain.

Let me not forget light. I mean the opposite of darkness. The slow drawing aside of the night's curtain every morning to reveal the sun's emergence. Not much is reliable these days. In fact, is anything reliable? The sun is. I use its steadfastness every day to give me an anchor. Once again, there it is. Climbing upward. Unfaltering.

The senses. W.H. Auden called them "Precious Five." Sight, smell, touch, hearing, taste. What these times have made abundantly clear is that death is real, it's near, it's possible. The place I put death in my daily life before this was somewhere in the remote part of the Outer Banks of my mind. Not anymore. So, seeing things. Smelling things. Tasting things, touching and hearing things. With gratitude.

If this situation has done anything, it's stopped time. Or slowed it down considerably. Forced not to do most everything we used to do, we're left to observe and experience what is directly before us, in every sense.

For those of us who are not sick or struggling, a gift many of us had forgotten.

Published on April 18, 2020 15:27

Six visions to be grateful for

Vision #1

I am walking in the city of Paris for the first time. It is 1972. I am twenty-seven years old. I will be living here for six months.

I have never seen streets like these, some wind and curve and some are straight but all of them have buildings of such stateliness and accomplishment on either side. I don't recognize some of the smells. I don't recognize the way the phones work, the Metro, the busses, how you buy things. This goes beyond language. I don't understand that all women in shops must be addressed as "Madame." It is uncomfortable but liberating. I am liberated from the notion, so beaten into my head, that America is the best and only place there is. I look around at the river Seine, and I see the Pont Neuf, and the Rue St. Jacques and the beautiful older women so confident and purposeful, and my real education begins.

My traveling companion and I have somehow managed to find an apartment on the villa d'Alésia, in the 14th arrondissement. It is a sculptor's studio with tall opaque glass windows that face the street and can be thrown open to let the world come in.

We live in a neighborhood where there is a wine store where you get your litre bottles, without labels, filled with wine that costs .50cts a bottle. There is a butcher shop that sells only horsemeat.

I, like so many thousands of others through the years, discover that I've never eaten bread before. That I never understood the idea of individual dignity in a café. That I didn't see the nobleness of a life as a waiter. That I didn't understand time, that Notre Dame existed as it does now in the 14th century. That building began in the 12th century. How can I process time like that?

All of this is mine for the months I live in Paris.

This city completes me, as the writer James Salter wrote. It makes me the person I was meant to be. I am coming to the place I have never been before but to which I have always belonged.

I am walking in the city of Paris for the first time. It is 1972. I am twenty-seven years old. I will be living here for six months.

I have never seen streets like these, some wind and curve and some are straight but all of them have buildings of such stateliness and accomplishment on either side. I don't recognize some of the smells. I don't recognize the way the phones work, the Metro, the busses, how you buy things. This goes beyond language. I don't understand that all women in shops must be addressed as "Madame." It is uncomfortable but liberating. I am liberated from the notion, so beaten into my head, that America is the best and only place there is. I look around at the river Seine, and I see the Pont Neuf, and the Rue St. Jacques and the beautiful older women so confident and purposeful, and my real education begins.

My traveling companion and I have somehow managed to find an apartment on the villa d'Alésia, in the 14th arrondissement. It is a sculptor's studio with tall opaque glass windows that face the street and can be thrown open to let the world come in.

We live in a neighborhood where there is a wine store where you get your litre bottles, without labels, filled with wine that costs .50cts a bottle. There is a butcher shop that sells only horsemeat.

I, like so many thousands of others through the years, discover that I've never eaten bread before. That I never understood the idea of individual dignity in a café. That I didn't see the nobleness of a life as a waiter. That I didn't understand time, that Notre Dame existed as it does now in the 14th century. That building began in the 12th century. How can I process time like that?

All of this is mine for the months I live in Paris.

This city completes me, as the writer James Salter wrote. It makes me the person I was meant to be. I am coming to the place I have never been before but to which I have always belonged.

Published on April 18, 2020 11:41

April 14, 2020

Pamela

New York, 1985. A sharp fall Saturday. Early afternoon. The air smelled cool and delicious. It was invigorating, like a shot of pure oxygen. I was walking up Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village when I saw her. She was standing on the corner of Eleventh Street about a block away. I could see her curly red hair in all its wild abundance, a crimson beacon. She was unmistakable. She didn’t recognize me at first, but as I got closer, her face became bright, as if it were a sun emerging from behind a cloud.

Pamela.

It was about 1pm. I would never have seen her out before eleven. She was nocturnal. When you saw her in the daytime, it was as if you’d awakened a sleeping owl. Daytime was alien to her. It always seemed as if she were adapting to it. The expression, “groping in the dark” needed to be “groping in the light” for Pamela.

“Pamela!” I said.She blinked, found the source of the words, then she laughed a beat or two.

“Hi, hello,” she said. Once again, I realized how tall she was, probably 5’ 10”. It was difficult to say because of the fullness of her hair. “What are you up to?” she said.

“Taking a walk. Such an incredible day. What about you?”

She had on a navy-blue pea coat. She wore a silk scarf tied in a series of complex, appealing swirls about her neck with a broad blue ribbon around the back of her hair. She always dressed with flair, with panache. I used to ask her, “How do you always dress so well? If I gave you a pair of galoshes and a towel for clothes, you’d look great.”She’d laugh—again, one or two beats. “I don’t think about it.”

So, there she was. When I said the word “walk” to her, she frowned slightly. She was not fond of exercise.“I’m still waking up,” she said. Just behind us, looking like a castle waiting to be sieged, was the Jefferson Market Library. A big, red brick anomaly that I loved. I glanced at the library clock. It was one-fifteen.

“I’m meeting Wilhem for brunch,” she said. She had full lips. She had the wan skin of redheads.“Wilhem?”

“Didn’t I tell you? I’ve got a new boyfriend. I’m in love.”“Wilhem? What’s that name?”

“Dutch. He’s Dutch.”“How’d you meet him?”

“I met him at a party. I’m a goner. He’s going to ruin me.”“What’s he do?”

“He does lots of things. Right now he works in a gallery in Soho. He’s got lots of ideas,” she said. “I’d like to meet this guy,” I said.

She continued her half-convincing lament. “I’m a goner. I’m like a teenager. I can’t think straight. Help me. I’m his sex slave. It’s pathetic.” She laughed at herself.

I couldn’t help but think of that Joni Mitchell line, “Help me, I’m falling in love again.”“Pamela,” I said, “it sounds like it’s a little too late for help.” I felt a pang of envy.

“Too late,” she said, as if repeating some kind of curse. “Too late. Yes, it’s too late.”I left her there in her predicament and went off on my Saturday walk. She might be helpless, but, unlike me on this beautiful fall day in New York, she was in love.

Pamela

Pamela

Published on April 14, 2020 05:28

April 12, 2020

The agony and ecstasy of Easter

Easter, 1953.

It was a small church in the country, about five miles from where we lived in Virginia Beach, Virginia. This is where my mother took us every Sunday—my brother, sister and me. It was an Episcopal church built with brick and wood like so many buildings in that part of southeastern Virginia, marked and influenced by the colonial past. We went reluctantly, my brother and I, especially in the summer, when baseball and barefooted freedom called to us. But there was no question of not going.

I knew some of the people who came and some my mother knew and some we only knew from those Sundays in church.

In this little Virginia church there were two days that were the mightiest, the most significant. They were Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Though they were two days apart, the two days could not have been more different.

We usually went to church on Good Friday. We had been taught the story in Sunday school, and the minister had led us up to this day each Sunday. We knew what was going to happen. We knew that Jesus was going to be nailed to the cross. But part of me didn’t want to believe. Part of me didn’t want to believe that his Father was going let his son die. It couldn’t be! As the time went by in the church, and the sad words from the Bible were read by the minister, I kept hoping that God would save his only son from dying. Maybe this time it would be different.

When the minister read those lines that Jesus said, “It is finished,” as he gave up the ghost, despair came over me. I felt a great sadness sweep through the church as well, as dark as the clouds that the Bible says covered the sky the afternoon Jesus was crucified. I went home with my mother feeling gloomy. It was a dark day in every way. Saturday was as well.

Then, at last, Easter Sunday. The one day you had to be in church. We dressed in our finest. My mother wore a wide-brimmed hat, a lovely dress, and she wore white gloves that inched up her forearms.

When we walked into the church, it was festooned with flowers. Sprawling, exorbitant arrangements everywhere, by the altar, and along the sides of the church. Easter came at the same time as our Virginia spring, so the windows of the church were thrown open and the smells from the flowers from outdoors entered and flowed about. Everything was bursting with promise. The women and girls were dressed in bright dresses, yellows I remember, chiefly, and they all wore elaborate Easter hats. They looked remarkable. Jesus had risen from the dead! He had come back from the dead and had walked the earth and then ascended into heaven to be with his father.

Everyone was relieved and smiling and we sang the celebratory hymns in gratitude and hope.

After the service we shook each other’s hands and wished each other Happy Easter. The Lord Had Risen! Praise the Lord! Everyone was joyous. From great despair to great joy in one weekend. My little body could hardly contain such wide swings of emotion.

We rode back home in my mother’s car. If the day was warm, and it often was, the windows we would be down and the sweet breeze would come into backseat of the car.

In a few years I would stop feeling these things as if they actually happened to a man who walked the earth. I would still go to church on Easter, though, still love the words and the music and the flowers and love seeing the women in their fine dresses and hats. But I would never again feel as I did as a boy in 1953 in Virginia that everything was so wrong with the world and then, just a few days later, suddenly, in a burst of wonder and awe, feel that everything was right with the world.

Published on April 12, 2020 05:49

April 1, 2020

Paris, when it drizzles

“Then there was the bad weather,” begins Ernest Hemingway’s memoir of living in Paris in the twenties, A Moveable Feast. “It would come in one day when the fall was over. We would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe. The leaves lay sodden in the rain and the wind drove the rain against the big green autobus in the terminal....”

Hemingway knew exactly what he was doing when he began his poem to Paris with a cold, rainy, windswept day. He knew that bad weather brings out the lyrical in Paris and in the visitor, too. It summons up feelings of regret, loss, sadness—and in the case of the first pangs of winter—intimations of mortality. The stuff of poetry. And of keen memories. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. Anyone who has not passed a chill, rainy day in Paris will have an incomplete vision of the city, and of him- or herself in it.

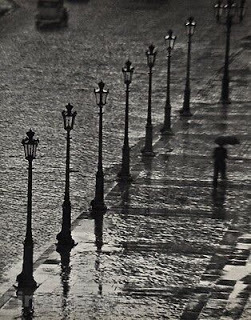

Great photographers like André Kertész understood how splendid Paris looks awash in gray and painted with rain. His book, J’aime Paris, shot entirely in black and white over the course of forty years, draws heavily on foul weather. I don’t know of anyone, with the possible exceptions of Atget and Cartier-Bresson, who has come closer to capturing the soul of Paris with a camera. The viewer will remember many of these photographs—even if he or she can’t name the photographer—because they have become part of the Parisian landscape in our minds’ eyes. That solitary man, his coat windblown as he walks toward wet cobblestones; the statue of Henry IV on horseback reflected in a puddle fringed by—yes—those sodden leaves. Kertész’s Paris sends a nostalgic chill through our bodies.

On one memorable trip to Paris, it rained. When it didn’t rain, it threatened to. This was in October, so leaves were starting to fall from trees, and that added a sense of forlornness to my visit. Each morning, I stepped out from my hotel on the Left Bank just off the Boulevard St. Germain into a dull gray morning. The sky hung low, the color of graphite, and it seemed just as heavy. The air was cool and dense.

But I wasn’t disappointed. After a shot of bitter espresso, I was ready to go. That week in October I set myself the goal of following the flow of the Seine, walking from one end of Paris to the other. I had bad weather as my companion, and a good one it was, too. I walked along the quays and over the bridges in a soft drizzle. The colossal bronze figures that hang off the side of the Pont Mirabeau were wet and streaming. The Eiffel Tower lost its summit in the fog. The cars and autobuses made hissing noises as they flowed by on wet pavement. The Seine was flecked with pellets of rain. The dark, varnished houseboats, so long a fixture on the river, had their lights shining invitingly out of pilothouses. The facade of Notre Dame in the gloom sent a medieval shudder through me. None of this I would have seen in the sunlight.

Then there is the matter of food.

There may be no Parisian experience as gratifying as walking out of the rain or cold into a welcoming, warm bistro. There is the taking off of the heavy wet coat and hat and then the sitting down to one of the meals the French seemed to have created expressly for days such as this: pot-au-feu or cassoulet or choucroute.

I remember one rainy day on this trip in particular. I walked in out of the wet, sat down and ordered the house specialty, pot-au-feu. For those unfamiliar with this poem, do not seek enlightenment in the dictionary. It will tell you that pot-au-feu is “a dish of boiled meat and vegetables, the broth of which is usually served separately.” This sounds like British cooking, not French, and the dictionary should be sued for libel. My spirits rose as the large smoking bowl was brought to my table along with bread and wine. I let the broth rise up to my face, the concentrated beauty of France. Then I took that first large spoonful into my mouth. The savory meat and vegetables and intense broth traveled to my belly. I was restored.

Paris, photo by André Kertész

Paris, photo by André Kertész

I sat and ate in the bistro and watched the people hurry by outside bent against the weather. I heard the tat, tat, tat of the rain as it beat against the bistro glass. The trees on the street were skeletal and looked defenseless. Where had I seen this before? In what book of photographs about Paris? I looked around inside and saw others like myself being braced by a meal such as mine and by the warmth of the room. The sounds of conversation and of crockery softly rattling filled the air. Efficient waiters flowed by, distinguished men with long white aprons, working elegantly. Delicious food was being brought out of the kitchen, and I watched as it was put in front of expectant diners. Every so often the front door would open, and a new refugee would enter, shuddering, with umbrella and dripping coat, a dramatic reminder that outside was no cinema.

I finished my meal slowly. I had left almost all vestiges of cold behind. My waiter took the plates away. Then he brought me a small, potent espresso. I lingered over it, savoring each drop. I looked outside. It would be good to stay here a bit longer.

I got up to go. Paris—gloomy, darkly beautiful Paris—was waiting.

Hemingway knew exactly what he was doing when he began his poem to Paris with a cold, rainy, windswept day. He knew that bad weather brings out the lyrical in Paris and in the visitor, too. It summons up feelings of regret, loss, sadness—and in the case of the first pangs of winter—intimations of mortality. The stuff of poetry. And of keen memories. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. Anyone who has not passed a chill, rainy day in Paris will have an incomplete vision of the city, and of him- or herself in it.

Great photographers like André Kertész understood how splendid Paris looks awash in gray and painted with rain. His book, J’aime Paris, shot entirely in black and white over the course of forty years, draws heavily on foul weather. I don’t know of anyone, with the possible exceptions of Atget and Cartier-Bresson, who has come closer to capturing the soul of Paris with a camera. The viewer will remember many of these photographs—even if he or she can’t name the photographer—because they have become part of the Parisian landscape in our minds’ eyes. That solitary man, his coat windblown as he walks toward wet cobblestones; the statue of Henry IV on horseback reflected in a puddle fringed by—yes—those sodden leaves. Kertész’s Paris sends a nostalgic chill through our bodies.

On one memorable trip to Paris, it rained. When it didn’t rain, it threatened to. This was in October, so leaves were starting to fall from trees, and that added a sense of forlornness to my visit. Each morning, I stepped out from my hotel on the Left Bank just off the Boulevard St. Germain into a dull gray morning. The sky hung low, the color of graphite, and it seemed just as heavy. The air was cool and dense.

But I wasn’t disappointed. After a shot of bitter espresso, I was ready to go. That week in October I set myself the goal of following the flow of the Seine, walking from one end of Paris to the other. I had bad weather as my companion, and a good one it was, too. I walked along the quays and over the bridges in a soft drizzle. The colossal bronze figures that hang off the side of the Pont Mirabeau were wet and streaming. The Eiffel Tower lost its summit in the fog. The cars and autobuses made hissing noises as they flowed by on wet pavement. The Seine was flecked with pellets of rain. The dark, varnished houseboats, so long a fixture on the river, had their lights shining invitingly out of pilothouses. The facade of Notre Dame in the gloom sent a medieval shudder through me. None of this I would have seen in the sunlight.

Then there is the matter of food.

There may be no Parisian experience as gratifying as walking out of the rain or cold into a welcoming, warm bistro. There is the taking off of the heavy wet coat and hat and then the sitting down to one of the meals the French seemed to have created expressly for days such as this: pot-au-feu or cassoulet or choucroute.

I remember one rainy day on this trip in particular. I walked in out of the wet, sat down and ordered the house specialty, pot-au-feu. For those unfamiliar with this poem, do not seek enlightenment in the dictionary. It will tell you that pot-au-feu is “a dish of boiled meat and vegetables, the broth of which is usually served separately.” This sounds like British cooking, not French, and the dictionary should be sued for libel. My spirits rose as the large smoking bowl was brought to my table along with bread and wine. I let the broth rise up to my face, the concentrated beauty of France. Then I took that first large spoonful into my mouth. The savory meat and vegetables and intense broth traveled to my belly. I was restored.

Paris, photo by André Kertész

Paris, photo by André KertészI sat and ate in the bistro and watched the people hurry by outside bent against the weather. I heard the tat, tat, tat of the rain as it beat against the bistro glass. The trees on the street were skeletal and looked defenseless. Where had I seen this before? In what book of photographs about Paris? I looked around inside and saw others like myself being braced by a meal such as mine and by the warmth of the room. The sounds of conversation and of crockery softly rattling filled the air. Efficient waiters flowed by, distinguished men with long white aprons, working elegantly. Delicious food was being brought out of the kitchen, and I watched as it was put in front of expectant diners. Every so often the front door would open, and a new refugee would enter, shuddering, with umbrella and dripping coat, a dramatic reminder that outside was no cinema.

I finished my meal slowly. I had left almost all vestiges of cold behind. My waiter took the plates away. Then he brought me a small, potent espresso. I lingered over it, savoring each drop. I looked outside. It would be good to stay here a bit longer.

I got up to go. Paris—gloomy, darkly beautiful Paris—was waiting.

Published on April 01, 2020 03:41

March 15, 2020

Letter from the Crescent City

I'm sitting at a coffee shop on Royal Street in the Marigny neighborhood of New Orleans, not far from the French Quarter. It's 9am on a Sunday. Aside from me, two people are here, not including the owner and the barista. It's early, though, for this city. I asked the owner, Fred, how business was. "Not bad." But he's not complacent. He's sanitizing the hell out of tables and door handles. Will he shut down? "I may have to."

1400 miles away, in New York City, my daughter lives. I was supposed to see her one-woman show last week, but she urged me not to come. It would make her too anxious to have me there. I'm 74. Prime real estate for the virus. So, I didn't go, missing an event a father shouldn't miss. I know. There are a lot more serious situations. Thousands like mine, many much worse.

Do I feel guilty asking the gods to take special care of my daughter, to protect her, and to guard her from harm?

No.

Published on March 15, 2020 07:13

March 7, 2020

A very great and very funny French writer

French writers.

They're of two sorts, IMO. One are the writers who draw form their minds. To wit: Corneille and Racine. Voltaire and Sartre. I think many French see themselves as intellectual aristocrats, and that's one reason they worship those dudes.

But the other great French writers, those who write from the heart—not without great skill and mental prowess—are the giants, to my mind.

At the pinnacle, Molière and Balzac.

I doubt anyone would contest Balzac. But I would wager most French wouldn't place Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, aka, Molière, at the very top. I'm on shaky ground, of course, not being French. How dare I! Well, as the French say, enfoiré! Roughly translated—well, look it up.

One reason, I think, is because Molière is funny. Comic writers have always securely occupied a second rung in literature, never the first. Which is fucking ridiculous.

But who is not one of the greatest writers who ever lived if not Cervantes, a comic writer to the marrow?

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

To wit. In his play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), a doctor is trying to woo a young woman. To entice her, he proposes:

"...I invite you to come see one of these days, to amuse yourself, the dissection of a woman, about whom I'll lecture."

The woman's servant drily replies:

"A very agreeable amusement. There are some who would take their lady love to a play, but a dissection is something much more gallant."

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

In fact, Le Malade imaginaire was Molière's last play. Sick with TB, he insisted, in true theatrical tradition, that the show must go on. He collapsed and died shortly thereafter. He was refused burial in sacred ground because he was an actor. WTF? Never mind that he was also an author. 144 years later, the French woke up and had his remains transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery.

What I would give to see what he would do with our present times.

They're of two sorts, IMO. One are the writers who draw form their minds. To wit: Corneille and Racine. Voltaire and Sartre. I think many French see themselves as intellectual aristocrats, and that's one reason they worship those dudes.

But the other great French writers, those who write from the heart—not without great skill and mental prowess—are the giants, to my mind.

At the pinnacle, Molière and Balzac.

I doubt anyone would contest Balzac. But I would wager most French wouldn't place Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, aka, Molière, at the very top. I'm on shaky ground, of course, not being French. How dare I! Well, as the French say, enfoiré! Roughly translated—well, look it up.

One reason, I think, is because Molière is funny. Comic writers have always securely occupied a second rung in literature, never the first. Which is fucking ridiculous.

But who is not one of the greatest writers who ever lived if not Cervantes, a comic writer to the marrow?

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.To wit. In his play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), a doctor is trying to woo a young woman. To entice her, he proposes:

"...I invite you to come see one of these days, to amuse yourself, the dissection of a woman, about whom I'll lecture."

The woman's servant drily replies:

"A very agreeable amusement. There are some who would take their lady love to a play, but a dissection is something much more gallant."

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves. In fact, Le Malade imaginaire was Molière's last play. Sick with TB, he insisted, in true theatrical tradition, that the show must go on. He collapsed and died shortly thereafter. He was refused burial in sacred ground because he was an actor. WTF? Never mind that he was also an author. 144 years later, the French woke up and had his remains transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery.

What I would give to see what he would do with our present times.

Published on March 07, 2020 05:56

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin

French writers.

They're of two sorts, IMO. One are the writers who draw form their minds. To wit: Corneille and Racine. Voltaire and Sartre. I think many French see themselves as intellectual aristocrats, and that's one reason they worship those dudes.

But the other great French writers, those who write from the heart—not without great skill and mental prowess—are the giants, to my mind.

At the pinnacle, Molière and Balzac.

I doubt anyone would contest Balzac. But I would wager most French wouldn't place Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, aka, Molière, at the very top. I'm on shaky ground, of course, not being French. How dare I! Well, as the French say, enfoiré! Roughly translated—well, look it up.

One reason, I think, is because Molière is funny. Comic writers have always securely occupied a second rung in literature, never the first. Which is fucking ridiculous.

But who is not one of the greatest writers who ever lived if not Cervantes, a comic writer to the marrow?

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

To wit. In his play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), a doctor is trying to woo a young woman. To entice her, he proposes:

"...I invite you to come see one of the days, to amuse yourself, the dissection of a woman, about whom I'll lecture."

The woman's servant drily replies:

"A very agreeable amusement. There are some who would take their lady love to a play, but a dissection is something much more gallant."

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

In fact, Le Malade imaginaire was Molière's last play. Sick with TB, he insisted, in true theatrical tradition, that the show must go on. He collapsed and died shortly thereafter. He was refused burial in sacred ground because he was an actor. WTF? Never mind that he was also an author. 144 years later, the French woke up and had his remains transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery.

What I would give to see what he would do with our present times.

They're of two sorts, IMO. One are the writers who draw form their minds. To wit: Corneille and Racine. Voltaire and Sartre. I think many French see themselves as intellectual aristocrats, and that's one reason they worship those dudes.

But the other great French writers, those who write from the heart—not without great skill and mental prowess—are the giants, to my mind.

At the pinnacle, Molière and Balzac.

I doubt anyone would contest Balzac. But I would wager most French wouldn't place Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, aka, Molière, at the very top. I'm on shaky ground, of course, not being French. How dare I! Well, as the French say, enfoiré! Roughly translated—well, look it up.

One reason, I think, is because Molière is funny. Comic writers have always securely occupied a second rung in literature, never the first. Which is fucking ridiculous.

But who is not one of the greatest writers who ever lived if not Cervantes, a comic writer to the marrow?

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.

MolièreMolière (1622-1673) was and IS funny. He's more than that, natch. A great satirist. (Got him in trouble.) but, in the end, he makes you laugh. Still, 350-odd years later.To wit. In his play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), a doctor is trying to woo a young woman. To entice her, he proposes:

"...I invite you to come see one of the days, to amuse yourself, the dissection of a woman, about whom I'll lecture."

The woman's servant drily replies:

"A very agreeable amusement. There are some who would take their lady love to a play, but a dissection is something much more gallant."

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves.

A scene from an American production of The Imaginary InvalidTo get an idea of how brilliant Molière was/is, all you need to do is to check out any of Richard Wilbur's translations. They are masterpieces in themselves. In fact, Le Malade imaginaire was Molière's last play. Sick with TB, he insisted, in true theatrical tradition, that the show must go on. He collapsed and died shortly thereafter. He was refused burial in sacred ground because he was an actor. WTF? Never mind that he was also an author. 144 years later, the French woke up and had his remains transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery.

What I would give to see what he would do with our present times.

Published on March 07, 2020 05:56

March 1, 2020

Art for art's sake, and ours

Went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few days ago. (Umpeenth time.) Perfect museum day—gray, rainy. Walked three hours, randomly. The Met is so cached with art, it's hard to fathom.

Yes, Met's a big place. That's not the subject of today's monologue, though.

The subject is the splendor of what we've made in the brief time we've inhabited this blessed plot.

You don't need me to inform you of the destruction and pain humans have caused. That's The NeverEnding Story.

But so is art.

To spend three hours in the Met walking aimlessly as you would down the streets of a foreign city, is to drink draughts of panoramic beauty.

In the Met can you experience the sheer array of thousands of years of human artistic efforts. You can see Egyptian jewelry from four thousand years ago crafted by an anonymous master...

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper.

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper.

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 You can see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 You can see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

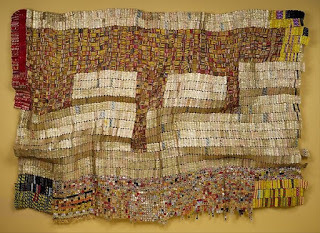

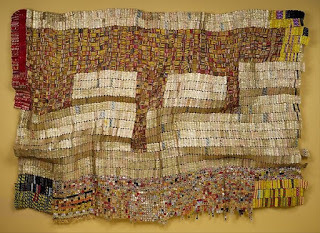

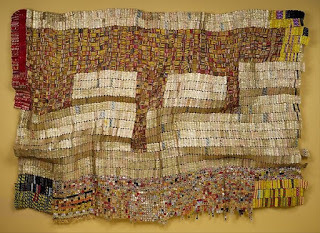

...and, a short stroll away, a silk and metal textile by a contemporary Ghanaian master.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006Etc.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006Etc.

We see enough of ourselves at our worst.

It's helpful, once every while, to see ourselves at our best.

Yes, Met's a big place. That's not the subject of today's monologue, though.

The subject is the splendor of what we've made in the brief time we've inhabited this blessed plot.

You don't need me to inform you of the destruction and pain humans have caused. That's The NeverEnding Story.

But so is art.

To spend three hours in the Met walking aimlessly as you would down the streets of a foreign city, is to drink draughts of panoramic beauty.

In the Met can you experience the sheer array of thousands of years of human artistic efforts. You can see Egyptian jewelry from four thousand years ago crafted by an anonymous master...

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper.

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper. "From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 You can see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 You can see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot... Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C....and, a short stroll away, a silk and metal textile by a contemporary Ghanaian master.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006Etc.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006Etc.We see enough of ourselves at our worst.

It's helpful, once every while, to see ourselves at our best.

Published on March 01, 2020 05:05

An entire building

Went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few days ago. (Umpeenth time.) Perfect museum day, gray, rainy. Spent three hours randomly wandering. The Met is so groaning with art it's hard to fathom. Just when I thought there wasn't a room or nook I hadn't seen, I stumbled into an undiscovered cache.

Yes, Met's a big place. That's not the subject of today's monologue, though.

The subject is the sheer magnitude of what we've made in the brief time we've inhabited this blessed plot.

You don't need me to inform you of the destruction and pain humans have caused. That's The NeverEnding Story.

But so is art.

To spend three hours in the Met, with no agenda, walking aimlessly as you would down the streets of a foreign city, is to drink deep draughts of beauty.

In a great museum can you experience the sheer array of thousands of years of human artistic efforts. Where else can you see Egyptian jewelry from three thousand years ago by an anonymous master...

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper?

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper?

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 Where else can you see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 Where else can you see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

...and, a short stroll away, a breathtaking textile by a contemporary Ghanaian master?

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006We're at our best in a museum like the Met. Good to be remined we're capable of a best.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006We're at our best in a museum like the Met. Good to be remined we're capable of a best.

Yes, Met's a big place. That's not the subject of today's monologue, though.

The subject is the sheer magnitude of what we've made in the brief time we've inhabited this blessed plot.

You don't need me to inform you of the destruction and pain humans have caused. That's The NeverEnding Story.

But so is art.

To spend three hours in the Met, with no agenda, walking aimlessly as you would down the streets of a foreign city, is to drink deep draughts of beauty.

In a great museum can you experience the sheer array of thousands of years of human artistic efforts. Where else can you see Egyptian jewelry from three thousand years ago by an anonymous master...

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper?

Necklace of Princess Sithathoryunet, ca. 1880 B.C., Middle Kingdom, Egypt..and a somberly inspiring view of New York buildings seen from a bridge painted by Edward Hopper? "From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 Where else can you see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot...

"From Williamsburg Bridge" Edward Hopper 1928 Where else can you see an almost perfectly preserved Etruscan chariot... Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C.

Etruscan bronze chariot, 6th century B.C....and, a short stroll away, a breathtaking textile by a contemporary Ghanaian master?

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006We're at our best in a museum like the Met. Good to be remined we're capable of a best.

Textile by El Anatsui, Ghana, 2006We're at our best in a museum like the Met. Good to be remined we're capable of a best.

Published on March 01, 2020 05:05