Richard Goodman's Blog, page 25

January 7, 2020

The Thief of Dreams

With every new Donald Trump announcement or proclamation that draws on the worst in us, I think about my daughter.

She’s young, only twenty-six. Her life is really just beginning. She’s at the age where you make dreams about the future, think about the life you will lead, let your hopes and aspirations wander as they will. Anything is possible. All doors are open. This is a moment we cherish for our children and try our best to prepare them for. We had such moments when we were young. They only appear once, and they are glorious, full of exciting uncertainty and potential. In those moments, we can be anything, do anything. Why not?

I had that freedom to dream, that open chance at optimism, when I was young. Now that I’m not young, I know well how precious that dreaming was.But every morning I get up to some new haughty, unsettling declaration by Donald Trump that I know must infringe on those freshly minted dreams my daughter and others like her are making. His denial of climate change is possibly the most arrogant of his declarations. With that, he commandeers the safety and well-being of our planet and its people.

WBUR in Boston reported on the growing problem of climate anxiety. I have had conversations with younger people, some of whom have decided not to have children because of the precarious state of our future. What about the many of us who do have children?

It’s hard to build dreams, those most delicate of bridges, in such an atmosphere of darkness. I am so angry at Trump. I am angry at him for many reasons, but mainly I am angry at him for stealing the future.

How dare he. How dare he pollute the ability for young people to plan their futures in serenity and peace and with hope. I’m calling him out for the thief he is.

She’s young, only twenty-six. Her life is really just beginning. She’s at the age where you make dreams about the future, think about the life you will lead, let your hopes and aspirations wander as they will. Anything is possible. All doors are open. This is a moment we cherish for our children and try our best to prepare them for. We had such moments when we were young. They only appear once, and they are glorious, full of exciting uncertainty and potential. In those moments, we can be anything, do anything. Why not?

I had that freedom to dream, that open chance at optimism, when I was young. Now that I’m not young, I know well how precious that dreaming was.But every morning I get up to some new haughty, unsettling declaration by Donald Trump that I know must infringe on those freshly minted dreams my daughter and others like her are making. His denial of climate change is possibly the most arrogant of his declarations. With that, he commandeers the safety and well-being of our planet and its people.

WBUR in Boston reported on the growing problem of climate anxiety. I have had conversations with younger people, some of whom have decided not to have children because of the precarious state of our future. What about the many of us who do have children?

It’s hard to build dreams, those most delicate of bridges, in such an atmosphere of darkness. I am so angry at Trump. I am angry at him for many reasons, but mainly I am angry at him for stealing the future.

How dare he. How dare he pollute the ability for young people to plan their futures in serenity and peace and with hope. I’m calling him out for the thief he is.

Published on January 07, 2020 07:06

January 3, 2020

Reclaiming Hope

A great depression has settled on us. Not economic, but emotional, spiritual, psychic. Whereas in the past, if you said the future looks bleak, you could dismiss that as someone's opinion. That's not true anymore. I needn't go into the details about climate change, which everyone knows by now, and the dire predictions emanating from scientists. But it's real.

People do not know what to do. Anything they think of doing seems futile. No matter what, the inevitable will arrive, they say. The has produced a kind a paralysis. An inability to plan with any certainty. Why bother? And worst of all, it has caused the complete abandonment of hope.

Dante knew what he was talking about. The words he decided to write on the gates of hell in his great poem say, "Abandon all hope, you who enter here." What could be more devastating and more final than to deprive you of hope?

We have as our head of state a man who in everything he does crushes hope. We know, in our hearts, that if we had a leader committed to saving us from the sins we have committed as humans in harming the earth, then hope, and its first cousin--optimism--could flourish.

I have talked to people in their twenties who are, quite simply, continually depressed. They are in despair about the future. Some have children and do not know how they can assure their children about their lives. I have a daughter in her twenties. Every day, I internally apologize to her. I feel like crying all the time.

I've written about this before, in a post called The Thief of Dreams. The thief of dreams is Donald Trump. No person has the right to destroy someone's ability to hope and to dream.

Depression may be the most onerous of human emotions. Its strength is incalculable.

Right now, right this minute, we are under the sway of this collective depression. We have to summon all our will to combat it. How? We assume strength. We fight.

With all our might.

People do not know what to do. Anything they think of doing seems futile. No matter what, the inevitable will arrive, they say. The has produced a kind a paralysis. An inability to plan with any certainty. Why bother? And worst of all, it has caused the complete abandonment of hope.

Dante knew what he was talking about. The words he decided to write on the gates of hell in his great poem say, "Abandon all hope, you who enter here." What could be more devastating and more final than to deprive you of hope?

We have as our head of state a man who in everything he does crushes hope. We know, in our hearts, that if we had a leader committed to saving us from the sins we have committed as humans in harming the earth, then hope, and its first cousin--optimism--could flourish.

I have talked to people in their twenties who are, quite simply, continually depressed. They are in despair about the future. Some have children and do not know how they can assure their children about their lives. I have a daughter in her twenties. Every day, I internally apologize to her. I feel like crying all the time.

I've written about this before, in a post called The Thief of Dreams. The thief of dreams is Donald Trump. No person has the right to destroy someone's ability to hope and to dream.

Depression may be the most onerous of human emotions. Its strength is incalculable.

Right now, right this minute, we are under the sway of this collective depression. We have to summon all our will to combat it. How? We assume strength. We fight.

With all our might.

Published on January 03, 2020 03:34

December 28, 2019

We all need heroes

As a writer, I've had my share of dreams and fantasies. I've long since abandoned some of them--Nobel Prize, Pulitzer Prize, MacArthur Award and various other honors in a galaxy far, far away.

But then there are dreams and fantasies that may be highly unlikely, but not necessarily impossible. One of those is to tell my literary heroes (living, of course) how much they have meant to me. It's hard to describe how intimate a relationship you can have with someone you don't know when you're a writer. Those writers who have inspired you are often the only people who seem to understand what you're trying to do, even though you've never met them. They do, because, by writing, and by writing with passion and dedication, they tell you that what you're doing is worth it all.

Sometimes, they can even rescue you. Which is what happened to me. It was Laurence Wylie who did the rescuing. You probably don't know who he is. He wrote a wonderful book called Village in the Vaucluse about living in the South of France in the early 1950s in the hill village of Roussillon. Today, Roussillon is a hub of tourism, but not back then. Wylie went with his family to see what living in a small French village was like. The result is a sympathetic, fair, compelling and ultimately delightful book that takes the reader through all aspects of French village life, from birth to death.

So, how did Wylie rescue me? In the beginning months of living in my small village in the South of France, I was lost. I didn't understand a lot of the ways and means of the villagers. They weren't friendly. And they essentially didn't recognize me. I, of course, thought I would instantly become everyone's best friend. There were a lot of books in the house (owned by Americans, it turned out) I was living in, and one of them was Village in the Vaucluse. The landlady recommended it. I read it, and then everything was made plain. I saw my villagers in Wylie's book and understood I was no exception as to how they led their lives. I was fine after that.

When my book about living in that village was published, one of the first things I did was to send Laurence Wylie a copy in care of his publisher. Along with it, I sent a letter explaining how he had rescued me and how his book would live forever because it was true. I had no idea if he was even still alive at that point. It was forty years after Village in the Vaucluse had been published.

Then, one wonderful day, I received a handwritten letter from Laurence Wylie. This, in part, is what he wrote:

"Your letter was important to me because it helped me shove aside a sort of feeling that at 83 my life is dwindling without my having made a difference by living. Your letter made me feel that I had done something, so I thank you."

That was beyond great expectations.

Two years later, he was gone. But his book lives on, and I believe it always will.

But then there are dreams and fantasies that may be highly unlikely, but not necessarily impossible. One of those is to tell my literary heroes (living, of course) how much they have meant to me. It's hard to describe how intimate a relationship you can have with someone you don't know when you're a writer. Those writers who have inspired you are often the only people who seem to understand what you're trying to do, even though you've never met them. They do, because, by writing, and by writing with passion and dedication, they tell you that what you're doing is worth it all.

Sometimes, they can even rescue you. Which is what happened to me. It was Laurence Wylie who did the rescuing. You probably don't know who he is. He wrote a wonderful book called Village in the Vaucluse about living in the South of France in the early 1950s in the hill village of Roussillon. Today, Roussillon is a hub of tourism, but not back then. Wylie went with his family to see what living in a small French village was like. The result is a sympathetic, fair, compelling and ultimately delightful book that takes the reader through all aspects of French village life, from birth to death.

So, how did Wylie rescue me? In the beginning months of living in my small village in the South of France, I was lost. I didn't understand a lot of the ways and means of the villagers. They weren't friendly. And they essentially didn't recognize me. I, of course, thought I would instantly become everyone's best friend. There were a lot of books in the house (owned by Americans, it turned out) I was living in, and one of them was Village in the Vaucluse. The landlady recommended it. I read it, and then everything was made plain. I saw my villagers in Wylie's book and understood I was no exception as to how they led their lives. I was fine after that.

When my book about living in that village was published, one of the first things I did was to send Laurence Wylie a copy in care of his publisher. Along with it, I sent a letter explaining how he had rescued me and how his book would live forever because it was true. I had no idea if he was even still alive at that point. It was forty years after Village in the Vaucluse had been published.

Then, one wonderful day, I received a handwritten letter from Laurence Wylie. This, in part, is what he wrote:

"Your letter was important to me because it helped me shove aside a sort of feeling that at 83 my life is dwindling without my having made a difference by living. Your letter made me feel that I had done something, so I thank you."

That was beyond great expectations.

Two years later, he was gone. But his book lives on, and I believe it always will.

Published on December 28, 2019 06:13

December 17, 2019

Richard Goodman's Christmas for the Lonely and the Depressed

Having spent my share of sad, dreadful, double-up-on-the-anti-depressants-Christmases, counting the hours until the fucking holiday was over, I thought I might create a way of not just surviving but actually coping with Christmas—and invite you along.

What we're going to do here is to create a Christmas so bleak and desperate that nothing can be as bad ever. And we'll do it together!

We'll start Richard Goodman's Christmas on Christmas Eve, because that's when things get serious, don't they? All the happy people are huddled by the fire drinking their mulled wine and saying things like, "Ok, you can open one present--but only one!!!!!"

Not us!!!! We'll be headed to the New York City subway system. We're going to catch the F train at 34th Street, a particularly crowded, noisy station, at 6pm and ride the train for the next three hours back and forth. The train will be extremely crowded because of the hour, and I will have arranged to have six out-of-tune street singers perform, without stopping, directly in front of you.

At 9PM we'll get off the subway back at 34th Street. We will emerge at Herald Square and walk west to the Hudson River. On the way, we'll dine at White Castle, a hamburger chain known for its harsh fluorescent interiors and for being high on the Board of Health's watch list.

After dining, we'll head to the Hudson River where, if my past experience is any guide, it will be cold and windy and dark. We'll stand there for two hours, shivering.

Eleven o'clock! Time to head to the pay-by-the-hour motel I've booked you in just up the way on Eleventh Avenue near the Lincoln Tunnel. The noise and pollution will keep you up most of the night. But that's a good thing! Because you won't need a wake-up call!

Christmas day! This is the heart of the Richard Goodman Christmas!!!

We'll meet at 5am at New York's famed Port Authority bus terminal!! Here's we'll enjoy a holiday breakfast of coffee in a Styrofoam cup and stale doughnuts. Then we'll hop on a bus for a day in Staten Island, in one of the most isolated and xenophobic neighborhoods in New York, if not the world—New Springville. We'll knock on random front doors starting at 7am wishing the homeowners, "Merry Christmas!!! Unless you're Jewish!!!!" Then we'll sing "The Little Drummer Boy" six times to the lucky person who answers the door. Those of us who are met with some hostility or even physical harm will be left to fend for themselves.

Time for presents!!!

Each one of you will have been given $3 to spend at the Dollar Store to purchase your gift. And each of you will have the name of one person in the group who you exchange gifts with. This ceremony will take place in an empty parking lot.

Time to have our big Christmas meal!!

We're going to a dumpster!!! This dumpster, located in back of a local high school, will have treats from the two or three cafeteria meals the kids ate! Chances are, you won't be able to determine what it is you're eating—but, hey, this is an adventure!!

After our sumptuous meal, we'll take the bus back to Port Authority for an afternoon of pornographic films on Eighth Avenue!! You'll be able to choose from classics like, "Inside Mrs. Claus," "Rudolph the Rimming Reindeer" and "Bite Christmas."

Guess what? The holiday is almost over! But not before we have our holiday toast. We'll gather at Shaney's Irish Bar on the Bowery, known as one of the last bars for the downtrodden, where you can get a 50cent beer in an unwashed class!!! What better way to close out our Christmas together.

We'll raise our glasses and make a toast! "Thank God it's only once a year!!"

So, I hope you'll join me this Christmas for an incredible experience!! It's just $53, which includes subway ticket and your room at the Tunnel Motel.

Let's celebrate the holiday together—the Richard Goodman way!! No Christmas will ever seem as depressing again!!!

What we're going to do here is to create a Christmas so bleak and desperate that nothing can be as bad ever. And we'll do it together!

We'll start Richard Goodman's Christmas on Christmas Eve, because that's when things get serious, don't they? All the happy people are huddled by the fire drinking their mulled wine and saying things like, "Ok, you can open one present--but only one!!!!!"

Not us!!!! We'll be headed to the New York City subway system. We're going to catch the F train at 34th Street, a particularly crowded, noisy station, at 6pm and ride the train for the next three hours back and forth. The train will be extremely crowded because of the hour, and I will have arranged to have six out-of-tune street singers perform, without stopping, directly in front of you.

At 9PM we'll get off the subway back at 34th Street. We will emerge at Herald Square and walk west to the Hudson River. On the way, we'll dine at White Castle, a hamburger chain known for its harsh fluorescent interiors and for being high on the Board of Health's watch list.

After dining, we'll head to the Hudson River where, if my past experience is any guide, it will be cold and windy and dark. We'll stand there for two hours, shivering.

Eleven o'clock! Time to head to the pay-by-the-hour motel I've booked you in just up the way on Eleventh Avenue near the Lincoln Tunnel. The noise and pollution will keep you up most of the night. But that's a good thing! Because you won't need a wake-up call!

Christmas day! This is the heart of the Richard Goodman Christmas!!!

We'll meet at 5am at New York's famed Port Authority bus terminal!! Here's we'll enjoy a holiday breakfast of coffee in a Styrofoam cup and stale doughnuts. Then we'll hop on a bus for a day in Staten Island, in one of the most isolated and xenophobic neighborhoods in New York, if not the world—New Springville. We'll knock on random front doors starting at 7am wishing the homeowners, "Merry Christmas!!! Unless you're Jewish!!!!" Then we'll sing "The Little Drummer Boy" six times to the lucky person who answers the door. Those of us who are met with some hostility or even physical harm will be left to fend for themselves.

Time for presents!!!

Each one of you will have been given $3 to spend at the Dollar Store to purchase your gift. And each of you will have the name of one person in the group who you exchange gifts with. This ceremony will take place in an empty parking lot.

Time to have our big Christmas meal!!

We're going to a dumpster!!! This dumpster, located in back of a local high school, will have treats from the two or three cafeteria meals the kids ate! Chances are, you won't be able to determine what it is you're eating—but, hey, this is an adventure!!

After our sumptuous meal, we'll take the bus back to Port Authority for an afternoon of pornographic films on Eighth Avenue!! You'll be able to choose from classics like, "Inside Mrs. Claus," "Rudolph the Rimming Reindeer" and "Bite Christmas."

Guess what? The holiday is almost over! But not before we have our holiday toast. We'll gather at Shaney's Irish Bar on the Bowery, known as one of the last bars for the downtrodden, where you can get a 50cent beer in an unwashed class!!! What better way to close out our Christmas together.

We'll raise our glasses and make a toast! "Thank God it's only once a year!!"

So, I hope you'll join me this Christmas for an incredible experience!! It's just $53, which includes subway ticket and your room at the Tunnel Motel.

Let's celebrate the holiday together—the Richard Goodman way!! No Christmas will ever seem as depressing again!!!

Published on December 17, 2019 07:05

November 28, 2019

Thankful

Thankful for so many things.

I am thankful most for my beautiful daughter, Becky. The best thing to happen to me in my life is being the father of this radiant, brilliant young woman.

I am thankful for being alive. For my good health.

For light; The English language; olive oil; Thoreau; pencils; walking; kissing; travel; reading; Hemingway; museums.

For laughing; storms; Paris; writing; birds; learning; the ocean. For outdoor showers; Maine; surfcasting; Henry Miller; Willa Cather; Flaubert's letters.

For peaches; the moon; The Great Gatsby; Southern food/soul food.

For my memory.

For music; M.F.K. Fisher; Giotto; books; Van Gogh; French bookstores; the smell of moist soil.

For the sound of rain; dogs; New York City; fall, winter, spring, summer. For walking in Paris; Ralph Ellison; Velázquez; Verdi; back country roads; blues music.

For my sister; snow falling down; road trips; going to sleep when I'm exhausted; tea; kayaking. For Van Morrison; the Italian language; my bicycle; Michelin maps; Francois Truffaut; tomatoes; tall, slim pine trees; Tennessee Williams.

For old docks; going barefoot; women in summer dresses; friendship; work; porches; the songs of birds; Balzac; my body, every supple, practical, miraculous part of it; for water.

For sight.

For garlic; Cole Porter; West Fourth Street in New York City; John Waters; libraries; the smell of hay; sweat; the Seine; Rome; the stillness of early morning; Pablo Neruda's poetry.

For Langston Hughes; Greenwich Village; warblers; kindness; pastrami; bellylaughs; breathing; Lucinda Williams; the smell of suntan lotion at the beach; dusk; coffee; soft breezes.

For brilliant sunsets; Central Park; Wellfleet oysters; stretching; friends' voices; affection; holding hands with a woman you love; the release of crying; watching my daughter grow up; John Lennon; truth.

I am thankful most for my beautiful daughter, Becky. The best thing to happen to me in my life is being the father of this radiant, brilliant young woman.

I am thankful for being alive. For my good health.

For light; The English language; olive oil; Thoreau; pencils; walking; kissing; travel; reading; Hemingway; museums.

For laughing; storms; Paris; writing; birds; learning; the ocean. For outdoor showers; Maine; surfcasting; Henry Miller; Willa Cather; Flaubert's letters.

For peaches; the moon; The Great Gatsby; Southern food/soul food.

For my memory.

For music; M.F.K. Fisher; Giotto; books; Van Gogh; French bookstores; the smell of moist soil.

For the sound of rain; dogs; New York City; fall, winter, spring, summer. For walking in Paris; Ralph Ellison; Velázquez; Verdi; back country roads; blues music.

For my sister; snow falling down; road trips; going to sleep when I'm exhausted; tea; kayaking. For Van Morrison; the Italian language; my bicycle; Michelin maps; Francois Truffaut; tomatoes; tall, slim pine trees; Tennessee Williams.

For old docks; going barefoot; women in summer dresses; friendship; work; porches; the songs of birds; Balzac; my body, every supple, practical, miraculous part of it; for water.

For sight.

For garlic; Cole Porter; West Fourth Street in New York City; John Waters; libraries; the smell of hay; sweat; the Seine; Rome; the stillness of early morning; Pablo Neruda's poetry.

For Langston Hughes; Greenwich Village; warblers; kindness; pastrami; bellylaughs; breathing; Lucinda Williams; the smell of suntan lotion at the beach; dusk; coffee; soft breezes.

For brilliant sunsets; Central Park; Wellfleet oysters; stretching; friends' voices; affection; holding hands with a woman you love; the release of crying; watching my daughter grow up; John Lennon; truth.

Published on November 28, 2019 04:04

November 14, 2019

Quincy

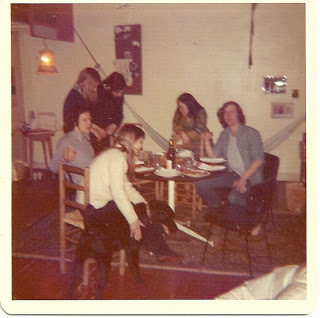

Quincy was my best friend Alex's cousin. She came, with her Greek boyfriend, Christo, to stay with us in Paris when we lived there in 1972. They also brought their black lab, Orion.

You can see her here, in the murky photo--God, I wish we'd taken better pictures--in a white sweater, her right hand resting on Orion's side. We're sitting at our table at 43 bis villa d'Alesia in Paris. That's me, on the right, long hair and all.

You can see her here, in the murky photo--God, I wish we'd taken better pictures--in a white sweater, her right hand resting on Orion's side. We're sitting at our table at 43 bis villa d'Alesia in Paris. That's me, on the right, long hair and all.

Quincy was a bright-spirited, highly-energetic woman who loved to walk around Paris. She was relentlessly cheerful and all but unstoppable. I would walk with her from time to time. She had a quirk of rubbing her thumb and forefinger together as she walked, the rubbing faster as the pace became more brisk. And it always did. She was slim, with long, fine brown hair and a ready smile. She had a sly sense of humor, and she was kind.

A few years after all of this, I was living in Cambridge, MA. Quincy came for a conference and visited me. It was so good to see her. We walked together around a lake, and I had a hard time keeping up with her. "What's the matter, Rich--have you let yourself go? Come on! Let's go!"

A few years after that, I got a call from Alex. Quincy had been in an automobile accident. Her spine had been severed. She was paralyzed from the waist down.

The great walker would walk no more.

Nothing makes any sense sometimes.

But in my mind's eye, I still see the Quincy from Paris and Cambridge. This is who will always be Quincy for me. The relentless walker, moving swiftly on the balls of her feet, on and on and on, urging me to keep up with her, and I can't.

You can see her here, in the murky photo--God, I wish we'd taken better pictures--in a white sweater, her right hand resting on Orion's side. We're sitting at our table at 43 bis villa d'Alesia in Paris. That's me, on the right, long hair and all.

You can see her here, in the murky photo--God, I wish we'd taken better pictures--in a white sweater, her right hand resting on Orion's side. We're sitting at our table at 43 bis villa d'Alesia in Paris. That's me, on the right, long hair and all. Quincy was a bright-spirited, highly-energetic woman who loved to walk around Paris. She was relentlessly cheerful and all but unstoppable. I would walk with her from time to time. She had a quirk of rubbing her thumb and forefinger together as she walked, the rubbing faster as the pace became more brisk. And it always did. She was slim, with long, fine brown hair and a ready smile. She had a sly sense of humor, and she was kind.

A few years after all of this, I was living in Cambridge, MA. Quincy came for a conference and visited me. It was so good to see her. We walked together around a lake, and I had a hard time keeping up with her. "What's the matter, Rich--have you let yourself go? Come on! Let's go!"

A few years after that, I got a call from Alex. Quincy had been in an automobile accident. Her spine had been severed. She was paralyzed from the waist down.

The great walker would walk no more.

Nothing makes any sense sometimes.

But in my mind's eye, I still see the Quincy from Paris and Cambridge. This is who will always be Quincy for me. The relentless walker, moving swiftly on the balls of her feet, on and on and on, urging me to keep up with her, and I can't.

Published on November 14, 2019 04:27

November 11, 2019

Changing

A strange thing has happened to me.

Not bad, just strange.

I remember when I was a kid, small kid, I read about a guy named Albert Schweitzer. I know who he is now, but back then, he was this white guy who went to Africa to help people. I don't think I even really knew where Africa was.

This was all in Life Magazine. Too bad for you who never got to experience that publication. It was a sprawling, lap-sized magazine that, really, told the story of America. Or part of it.

Schweitzer. A Life reporter asked him about his reverence for life, his belief of not killing any creature. He said something to the effect, "And that would include even a flea." I thought he was crazy.

Now, at 74, I'm finding that I find it hard to kill anything--yes, even a fly. If it's a moth or a spider or a wasp, I'll do my damndest to capture it with a paper towel and release it outside. Didn't do that before.

Perhaps getting older makes one sharper and clearer about life, being alive, what it is that makes someone or something alive. It is the great mystery. Holy, if anything. Albert Schweitzer

Albert Schweitzer

Not bad, just strange.

I remember when I was a kid, small kid, I read about a guy named Albert Schweitzer. I know who he is now, but back then, he was this white guy who went to Africa to help people. I don't think I even really knew where Africa was.

This was all in Life Magazine. Too bad for you who never got to experience that publication. It was a sprawling, lap-sized magazine that, really, told the story of America. Or part of it.

Schweitzer. A Life reporter asked him about his reverence for life, his belief of not killing any creature. He said something to the effect, "And that would include even a flea." I thought he was crazy.

Now, at 74, I'm finding that I find it hard to kill anything--yes, even a fly. If it's a moth or a spider or a wasp, I'll do my damndest to capture it with a paper towel and release it outside. Didn't do that before.

Perhaps getting older makes one sharper and clearer about life, being alive, what it is that makes someone or something alive. It is the great mystery. Holy, if anything.

Albert Schweitzer

Albert Schweitzer

Published on November 11, 2019 06:32

Taking out the trash

I grew up in Southeastern Virginia. When it was time for me to fly the coop as a young man, I went north to live. At age twenty-five, I settled in New York City. Like most sons and daughters, from time to time I would go home to visit. I'd never had the best of relationships with my father. We were not close. Nevertheless, I came to visit. He and my mother had divorced long ago, and he'd remarried and started a second family. It's too complicated and lengthy to go into our strained relationship, but there is one aspect of it that bears on this story.

My father was one of those fathers who wanted to dominate. He was the man in the house. I was not the man in the house. Instead of edging me toward manhood and my own way of encountering the world, he tried to maintain strict dominance.

But when I left, what was he going to to? I was earning my own money, paying my own bills, making my own decisions.

When I came home, though, he would wrest that independence from me, or try to. One of the ways he did this was by making me take out the trash. Now, what's wrong with that? Nothing--ostensibly. But in reality, combined with a lack of interest in what I did and with no conversation with me on an adult, man-to-man level, it became a way for him to reassert domination. Throw in a pinch of humiliation for good measure.

"Take out the trash," he would say. "Put it in the green container, not the gray one."

Now, here's the funny thing. I came to realize that this behavior is common to men who want to assert their authority. It is not unique to my father. It happened all over again when I was married. When my wife and and I used to visit her parents for the weekend. My in-laws were pleasant enough, and when my wife and I had a child, they were magnificent toward my daughter. The simple fact is, though, that my father-in-law had no interest in me whatsoever. He usually ignored me.

Except when it was time to take out the trash. That was my job. That was the most direct communication we had.

Again, what's wrong with that? Not the end of the world. Why not pitch in and not even think twice about it? Why make such a big deal about it?

Because it wasn't about pitching in. It was about hierarchy, about pecking order, about who's the man here, about, "I can make you take out the trash if I want to. And I want to."

The fact is that I never thought about it unless I was there, having to do it. I usually had a small flush of humiliation at being ordered to do this janitorial task. I did it, though. It took just a minute, then it was done. But it was the fact that these men could make me do this--at age twenty-five, thirty, forty, fifty--whenever they wanted, that made me bristle. And that, ultimately, even though the trash indeed did need taking out, they weren't ordering me to take it out for that reason. They were telling me to do it because they could. I got weary of that silverback stuff.

To the sons out there, has this happened to you? And to the daughters, is there the equivalent for you?

My father was one of those fathers who wanted to dominate. He was the man in the house. I was not the man in the house. Instead of edging me toward manhood and my own way of encountering the world, he tried to maintain strict dominance.

But when I left, what was he going to to? I was earning my own money, paying my own bills, making my own decisions.

When I came home, though, he would wrest that independence from me, or try to. One of the ways he did this was by making me take out the trash. Now, what's wrong with that? Nothing--ostensibly. But in reality, combined with a lack of interest in what I did and with no conversation with me on an adult, man-to-man level, it became a way for him to reassert domination. Throw in a pinch of humiliation for good measure.

"Take out the trash," he would say. "Put it in the green container, not the gray one."

Now, here's the funny thing. I came to realize that this behavior is common to men who want to assert their authority. It is not unique to my father. It happened all over again when I was married. When my wife and and I used to visit her parents for the weekend. My in-laws were pleasant enough, and when my wife and I had a child, they were magnificent toward my daughter. The simple fact is, though, that my father-in-law had no interest in me whatsoever. He usually ignored me.

Except when it was time to take out the trash. That was my job. That was the most direct communication we had.

Again, what's wrong with that? Not the end of the world. Why not pitch in and not even think twice about it? Why make such a big deal about it?

Because it wasn't about pitching in. It was about hierarchy, about pecking order, about who's the man here, about, "I can make you take out the trash if I want to. And I want to."

The fact is that I never thought about it unless I was there, having to do it. I usually had a small flush of humiliation at being ordered to do this janitorial task. I did it, though. It took just a minute, then it was done. But it was the fact that these men could make me do this--at age twenty-five, thirty, forty, fifty--whenever they wanted, that made me bristle. And that, ultimately, even though the trash indeed did need taking out, they weren't ordering me to take it out for that reason. They were telling me to do it because they could. I got weary of that silverback stuff.

To the sons out there, has this happened to you? And to the daughters, is there the equivalent for you?

Published on November 11, 2019 04:33

October 25, 2019

James Beard

I'm writing about James Beard, because he was a wonderful writer who deserves to be known by all who love good food and good writing.

I'm worried that too few people know who he was, except as the name affixed to a coveted award. He was a giant, figuratively and literally. He was born in 1903 and died in 1985.

He wrote over thirty cookbooks, and I have had a few through the years, but the one I've had for forty years and always return to with delight is James Beard's American Cookery. Some of it is dated—he has over thirty entries for "Candy," for example. But most of it isn't, and, more important, none of the writing is. I have yet to find a writer who knows more about American food and its history than James Beard. Each recipe is preceded by intriguing, highly informative prose about the dish and its background, often with a personal note. Beard draws on an enormous store of cookbooks and writers, many I'd never heard of. He seems sometimes to have one foot—maybe two—planted firmly in the early twentieth century—say, 1918. I feel, sometimes, as if I'm sitting around a boarding house table with him, the table groaning with fresh stews, vegetables, breads, puddings and pies. That would make perfect sense. His mother ran a boarding house in Portland, Oregon.

He didn't have to learn about farm-to-table, because that's where he came from. He only ate the freshest ingredients when he was a boy growing up in Oregon, and that's what he espoused from experience and taste. His family took summer trips to the Oregon coast, and that's where he learned about seafood. All of it fresh, of course.

I saw him once. In Greenwich Village, where he lived. He lived on West 12th Street, and so did I. I'm surprised I didn't see him more often, but one day, I did. It was in a little Italian Restaurant on Hudson Street, near Abingdon Square.

I must have been engrossed in my meal—it was a great little place, cheap with delicious food—because I didn't notice him when I walked in. At one point, I looked up and I saw him from behind, that enormous bald head and equally large frame. You know how you can identify certain people from behind? I knew it was James Beard. Of course, I also knew he lived in the neighborhood, so it made sense. This would have been about 1980, so he would have been in his early eighties. I was so pleased with myself for having seen him, as if I'd planned it. I only remember hearing one thing he said, in a soft voice,

"Everyone knows I'm a pussycat."

Lion, I'd say.

Published on October 25, 2019 06:57

October 19, 2019

The Truth of Fashion

Two years ago, Azzedine Alaïa died.

I wouldn't be surprised if you didn't know who he was. Unless you are familiar with the world of fashion, there's no reason you should know his name. He was a designer of women's clothes in the tradition of Dior, Yves St. Laurent, Givenchy, Armani.

He made dresses. Spectacular dresses. But dresses nonetheless.

Great designers, those who work in Paris or Milan, will have two distinct lines of clothing. They make one-of-a-kind dresses that cost extraordinary sums of money. And they make a line of clothing that is ready-to-wear. In French, it sounds classier, prêt-à-porter. Means the same thing.

In ready-to-wear, you do not get a dress that's unique, but the clothing can still be very expensive. A typical price for a ready-to-wear dress by Azzedine Alaïa is around $3000. The one below, a lot more.

Azzedine Alaïa and model

Azzedine Alaïa and model

It's very easy to dismiss the world of fashion, especially when it reaches upper heights of richdom. Especially at $3000 a pop. Cue the yearly income of a farmer in Bolivia, which is perhaps half that, probably far less.

But I've always loved fashion, especially high fashion. I've loved looking at the work of Christian Dior, for example. I'm transfixed by his designs. And, more recently, by the work of Emanuel Ungaro.

How can I justify paying more than 20 seconds attention to a business that caters to the rich and the vain? I dress in LL Bean and J. Crew on sale, quite happily. It seems so frivolous.

I justify it because of beauty. No, not the beauty of the women who wear the dresses. The beauty of the dresses themselves. The intricacy of the work, the immaculate detail of it, the creative use of fabric and hue. Dior was a superb craftsman, designer, artist.

Christian Dior, left, and right, with model

Christian Dior, left, and right, with model

There is probably something in your life that you lust for that is very expensive. Lust for--maybe admire, even worship in a way. Is it a Lamborghini? Is it a room at the Ritz in Paris? Is it Beluga Caviar? You'll never purchases these things, but you would if you could. Wouldn't you?

If I'm being honest, the few women I've met who can afford these dresses haven't been very interesting. I generally have found most very wealthy people to be boring. (Expect blowback, but who cares?)

I separate the garment and the craftsmanship, the artistry, from the people who wear it. All you need to do is thumb through the pages of any good book on Dior designs, and if you like beauty, you'll like at least some of his dresses very much. And, yes, I'm with Keats. Beauty is truth. Lies are ugly. And beauty never lies.

It's no coincidence that one of the top ten most-visited exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was the 2011 exhibition of the work of the British designer, Alexander McQueen. I was in Denver over Christmas, and the exhibit, Dior: From Paris to the World, was a smash at the Denver Museum.

So, RIP, Azzedine Alaïa and fellow creators of beauty. We can never have enough of that, in whatever form.

I wouldn't be surprised if you didn't know who he was. Unless you are familiar with the world of fashion, there's no reason you should know his name. He was a designer of women's clothes in the tradition of Dior, Yves St. Laurent, Givenchy, Armani.

He made dresses. Spectacular dresses. But dresses nonetheless.

Great designers, those who work in Paris or Milan, will have two distinct lines of clothing. They make one-of-a-kind dresses that cost extraordinary sums of money. And they make a line of clothing that is ready-to-wear. In French, it sounds classier, prêt-à-porter. Means the same thing.

In ready-to-wear, you do not get a dress that's unique, but the clothing can still be very expensive. A typical price for a ready-to-wear dress by Azzedine Alaïa is around $3000. The one below, a lot more.

Azzedine Alaïa and model

Azzedine Alaïa and modelIt's very easy to dismiss the world of fashion, especially when it reaches upper heights of richdom. Especially at $3000 a pop. Cue the yearly income of a farmer in Bolivia, which is perhaps half that, probably far less.

But I've always loved fashion, especially high fashion. I've loved looking at the work of Christian Dior, for example. I'm transfixed by his designs. And, more recently, by the work of Emanuel Ungaro.

How can I justify paying more than 20 seconds attention to a business that caters to the rich and the vain? I dress in LL Bean and J. Crew on sale, quite happily. It seems so frivolous.

I justify it because of beauty. No, not the beauty of the women who wear the dresses. The beauty of the dresses themselves. The intricacy of the work, the immaculate detail of it, the creative use of fabric and hue. Dior was a superb craftsman, designer, artist.

Christian Dior, left, and right, with model

Christian Dior, left, and right, with modelThere is probably something in your life that you lust for that is very expensive. Lust for--maybe admire, even worship in a way. Is it a Lamborghini? Is it a room at the Ritz in Paris? Is it Beluga Caviar? You'll never purchases these things, but you would if you could. Wouldn't you?

If I'm being honest, the few women I've met who can afford these dresses haven't been very interesting. I generally have found most very wealthy people to be boring. (Expect blowback, but who cares?)

I separate the garment and the craftsmanship, the artistry, from the people who wear it. All you need to do is thumb through the pages of any good book on Dior designs, and if you like beauty, you'll like at least some of his dresses very much. And, yes, I'm with Keats. Beauty is truth. Lies are ugly. And beauty never lies.

It's no coincidence that one of the top ten most-visited exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was the 2011 exhibition of the work of the British designer, Alexander McQueen. I was in Denver over Christmas, and the exhibit, Dior: From Paris to the World, was a smash at the Denver Museum.

So, RIP, Azzedine Alaïa and fellow creators of beauty. We can never have enough of that, in whatever form.

Published on October 19, 2019 06:36