Richard Goodman's Blog, page 24

February 24, 2020

Unrequested

I board the crosstown bus with two friends. All seats taken. But ride will be short. So, no sweat, standing, holding on to steel rail.

Woman seated just next to me looks up. "Would you like to sit?" she asks. I'm assuming she doesn't mean me. But—she's looking directly at me. At me. What, I think? What would prompt her to ask this absurd question?

I suddenly remember I'm 74. And I guess I must look it. This I hardly ever remember. That is, that I must look 74. But to her, I suppose, I'm an old guy.

I take action. "You're offering me your seat?????" I say to her. I have a strange, wild look in my eye.

"Uh...yes..." she says, with a slight tone of caution.

"So I suppose you think I'm old???"

"No, no...I...I just..."

I yank her up from her seat in one sure move. Then, telling everyone to stand back, I lift her above my head and begin twirling her around and around, à la early professional wrestling. She's actually pretty heavy, but I'm surprised at my strength. I suppose it's the adrenaline of anger.

"Offer me your seat, will you??" I cry as I increase my twirling speed. "Ha ha ha ha!! Now, what do you say? Now, who needs a seat???!!!!!" I see several hipsters in the back of the bus staring at me in horror.

"Catch!!!" I say to them and, in one graceful, economical move, toss the offending lady to them in the air.

A perfect throw, she lands with a thud in the their laps, unharmed.

"Anybody else want to fucking offer me THEIR SEAT???" I say, my eyes bulging as I look all around the bus. "Anybody want to go for a RIDE like the little lady just did? Anybody think I'm OLD and NEED to sit down, speak up or forever hold your peace!"

Heads bowed everywhere. Not a word spoken.

"Good," I say. "Very good."

I walk back to the woman's seat, which, of course, is empty. I sit down. I'm feeling my age, I have to admit.

Woman seated just next to me looks up. "Would you like to sit?" she asks. I'm assuming she doesn't mean me. But—she's looking directly at me. At me. What, I think? What would prompt her to ask this absurd question?

I suddenly remember I'm 74. And I guess I must look it. This I hardly ever remember. That is, that I must look 74. But to her, I suppose, I'm an old guy.

I take action. "You're offering me your seat?????" I say to her. I have a strange, wild look in my eye.

"Uh...yes..." she says, with a slight tone of caution.

"So I suppose you think I'm old???"

"No, no...I...I just..."

I yank her up from her seat in one sure move. Then, telling everyone to stand back, I lift her above my head and begin twirling her around and around, à la early professional wrestling. She's actually pretty heavy, but I'm surprised at my strength. I suppose it's the adrenaline of anger.

"Offer me your seat, will you??" I cry as I increase my twirling speed. "Ha ha ha ha!! Now, what do you say? Now, who needs a seat???!!!!!" I see several hipsters in the back of the bus staring at me in horror.

"Catch!!!" I say to them and, in one graceful, economical move, toss the offending lady to them in the air.

A perfect throw, she lands with a thud in the their laps, unharmed.

"Anybody else want to fucking offer me THEIR SEAT???" I say, my eyes bulging as I look all around the bus. "Anybody want to go for a RIDE like the little lady just did? Anybody think I'm OLD and NEED to sit down, speak up or forever hold your peace!"

Heads bowed everywhere. Not a word spoken.

"Good," I say. "Very good."

I walk back to the woman's seat, which, of course, is empty. I sit down. I'm feeling my age, I have to admit.

Published on February 24, 2020 07:46

February 20, 2020

Lies

From time to time, I meet someone who says, "I never lie."

Truly?

It's almost impossible for me to go through the day without telling some sort of lie. I lie in order not to hurt someone. Of course, the truth isn't necessarily called for when not asked for. But sometimes you are asked for it, and sometimes it's better not to provide it. When they ask, are you going to tell your child she or he wasn't less than wonderful, less than absolutely great, in the school recital? And if you do tell them they just weren't that good--which is the truth!--well, go live with the look on their face. But you can say you never lie!

Someone asked playwright Tracy Letts what he says when he sees a play written by a friend that he thinks is awful and the friend asks him his opinion.

"I lie!" Letts said. "I lie magnificently!"

I concur with what one of Graham Greene's characters has to say about this: "The truth, he thought, has never been of any real value to any human being—it is a symbol for mathematicians to pursue. In human relations kindness and lies are worth a thousand truths."

Of course, sometimes lying is despicable. If the intent is to deceive, to cause harm, simply to gain an advantage, well, it's an ugly thing to do. Sometimes you have to tell the truth. You're a coward if you don't. I often fail here. I lie when I shouldn't. I'm not proud of that.

In the end, I side with Tennessee Williams. I trust his sense of morality. What is a lie anyway? In A Streetcar Named Desire, Mitch confronts Blanche with some unsavory details about her past:

Mitch: You lied to me, Blanche.

Blanche: Don't say I lied to you.Mitch: Lies, lies, inside and out, all lies.Blanche: Never inside, I didn't lie in my heart...

TW was the same guy who said the worst sin is deliberate cruelty. And a lot of times a well-fabricated lie prevents me from being deliberately cruel. In those moments, I'm content to be a liar.

Truly?

It's almost impossible for me to go through the day without telling some sort of lie. I lie in order not to hurt someone. Of course, the truth isn't necessarily called for when not asked for. But sometimes you are asked for it, and sometimes it's better not to provide it. When they ask, are you going to tell your child she or he wasn't less than wonderful, less than absolutely great, in the school recital? And if you do tell them they just weren't that good--which is the truth!--well, go live with the look on their face. But you can say you never lie!

Someone asked playwright Tracy Letts what he says when he sees a play written by a friend that he thinks is awful and the friend asks him his opinion.

"I lie!" Letts said. "I lie magnificently!"

I concur with what one of Graham Greene's characters has to say about this: "The truth, he thought, has never been of any real value to any human being—it is a symbol for mathematicians to pursue. In human relations kindness and lies are worth a thousand truths."

Of course, sometimes lying is despicable. If the intent is to deceive, to cause harm, simply to gain an advantage, well, it's an ugly thing to do. Sometimes you have to tell the truth. You're a coward if you don't. I often fail here. I lie when I shouldn't. I'm not proud of that.

In the end, I side with Tennessee Williams. I trust his sense of morality. What is a lie anyway? In A Streetcar Named Desire, Mitch confronts Blanche with some unsavory details about her past:

Mitch: You lied to me, Blanche.

Blanche: Don't say I lied to you.Mitch: Lies, lies, inside and out, all lies.Blanche: Never inside, I didn't lie in my heart...

TW was the same guy who said the worst sin is deliberate cruelty. And a lot of times a well-fabricated lie prevents me from being deliberately cruel. In those moments, I'm content to be a liar.

Published on February 20, 2020 16:58

February 15, 2020

Laughing

I love to hear a big, unrestricted, peeling laugh. A laugh that gives fully to the moment. Those laughs usually sound like rapid-fire jackhammer bursts. There's nothing you can do to disguise your out-and-out happiness or you child-like appreciation of that moment that made you laugh. These can be accompanied by various bent over movements, head thrown back, eyes widened.

When was the last time you had a belly laugh? Have you ever laughed so hard you had to hit someone? Have you ever laughed so hard you actually fell down on the floor? I did, once, in a movie theater, when I saw Putney Swope, years ago, laughing so unrestrainedly I tumbled onto the theater aisle. God, what a wonderful moment.

Robin Williams had a laugh like that. You didn't hear it that often, because he was so busy making other people laugh, but if you go on YouTube and find places where he was with Jonathan Winters, you can hear it. It'll make you laugh, or at least smile. Jennifer Lawrence has a great laugh.

We learn a lot from the way a person laughs. In fact, of all the signals we get from people we don't know that well, their laugh may be the most telling. It's amazing to me how many laughs are mirthless. Those people who can't give themselves away, who laugh moderately, with restraint, without any theater, without any passion and release, are to be wary of, I think.

To let go with a big, uninhibited, raucous belly laugh takes not caring. You are so obviously a delighted mess. So obviously you. Nothing you wear, nothing you've done, nobody you know--nothing can protect you from the Woody Woodpecker, crazy happy noise that comes out of your mouth. I am a passenger on that ship of restraint from time to time, and I so regret it. Because laughing feels so damn great.

Of course, if you want to tap the source of genuine soul-satisfying laughter, if you want to learn how to really laugh again, listen to children. Especially to babies. Yes, babies. Because when you make a baby laugh, the sound is 100% pure undiluted joy. It's better than vitamins.

When was the last time you had a belly laugh? Have you ever laughed so hard you had to hit someone? Have you ever laughed so hard you actually fell down on the floor? I did, once, in a movie theater, when I saw Putney Swope, years ago, laughing so unrestrainedly I tumbled onto the theater aisle. God, what a wonderful moment.

Robin Williams had a laugh like that. You didn't hear it that often, because he was so busy making other people laugh, but if you go on YouTube and find places where he was with Jonathan Winters, you can hear it. It'll make you laugh, or at least smile. Jennifer Lawrence has a great laugh.

We learn a lot from the way a person laughs. In fact, of all the signals we get from people we don't know that well, their laugh may be the most telling. It's amazing to me how many laughs are mirthless. Those people who can't give themselves away, who laugh moderately, with restraint, without any theater, without any passion and release, are to be wary of, I think.

To let go with a big, uninhibited, raucous belly laugh takes not caring. You are so obviously a delighted mess. So obviously you. Nothing you wear, nothing you've done, nobody you know--nothing can protect you from the Woody Woodpecker, crazy happy noise that comes out of your mouth. I am a passenger on that ship of restraint from time to time, and I so regret it. Because laughing feels so damn great.

Of course, if you want to tap the source of genuine soul-satisfying laughter, if you want to learn how to really laugh again, listen to children. Especially to babies. Yes, babies. Because when you make a baby laugh, the sound is 100% pure undiluted joy. It's better than vitamins.

Published on February 15, 2020 03:40

February 8, 2020

Terrible Ted

I went to Cranbrook School, a private boys school in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, starting in 1958.

Cranbrook had an ice hockey team, but since I couldn't skate well, I never considered trying out for the team. I didn't know much about the sport.

I had a good friend at the school who was on the team, though, and I used to go to the school's rink, which was outside, to watch him practice. I would stand at one end and watch him sail around the rink on skates. He looked so graceful. One time, I noticed a grown man skating with the players. He wasn't the coach. I asked my friend who he was.

"Ted Lindsay," he said. "He helps out coaching from time to time."

Who was Ted Lindsay?

"He used to play for the Red Wings. Want to meet him?"

He meant the Detroit Red Wings. One of the six—at the time—National Hockey League teams. A little later my friend skated over with the man. He introduced me to Ted Lindsay. The man did not smile. He didn't exactly have a scowl, but he looked deadly serious. I learned later he had recently retired.

Then I noticed his face. It was unlike any face I'd ever seen. It was marked with countless jagged scars. They covered the landscape of his face. It was if his face were an abstract painting. There didn't seem to be one portion of it that wasn't marked by scars moving in all directions. I probably gasped. He was fearsome-looking. The fact that he didn't smile added to his fearsomeness. Later, I read that Lindsay had over 700 stitches on that face.

Ted Lindsay had played left wing on a storied line that included the legendary Gordie Howe, Wayne Gretsky's idol. He was called "Terrible Ted" by the press for his ferocity as a player. "I had no friends on the ice," he once said. He will be unknown to most Americans who do not know or love ice hockey. But I'm sure most every Canadian knows who Ted Lindsay, a native son, was.

Ted Lindsay

Ted Lindsay

I still remember that face. The over-abundant scars, the result of run-ins with fists and hockey sticks and perhaps skate blades as well. I'm sure Ted Lindsay had seen the astonished look I had on my face hundreds, maybe thousands of times. He probably counted on it as a player.

This was a face that a child might imagine the bogeyman having, who might spirit the child away from his home in the middle of the night. Suddenly, "There's no such thing as the bogeyman" lost all its meaning. There he was.

Cranbrook had an ice hockey team, but since I couldn't skate well, I never considered trying out for the team. I didn't know much about the sport.

I had a good friend at the school who was on the team, though, and I used to go to the school's rink, which was outside, to watch him practice. I would stand at one end and watch him sail around the rink on skates. He looked so graceful. One time, I noticed a grown man skating with the players. He wasn't the coach. I asked my friend who he was.

"Ted Lindsay," he said. "He helps out coaching from time to time."

Who was Ted Lindsay?

"He used to play for the Red Wings. Want to meet him?"

He meant the Detroit Red Wings. One of the six—at the time—National Hockey League teams. A little later my friend skated over with the man. He introduced me to Ted Lindsay. The man did not smile. He didn't exactly have a scowl, but he looked deadly serious. I learned later he had recently retired.

Then I noticed his face. It was unlike any face I'd ever seen. It was marked with countless jagged scars. They covered the landscape of his face. It was if his face were an abstract painting. There didn't seem to be one portion of it that wasn't marked by scars moving in all directions. I probably gasped. He was fearsome-looking. The fact that he didn't smile added to his fearsomeness. Later, I read that Lindsay had over 700 stitches on that face.

Ted Lindsay had played left wing on a storied line that included the legendary Gordie Howe, Wayne Gretsky's idol. He was called "Terrible Ted" by the press for his ferocity as a player. "I had no friends on the ice," he once said. He will be unknown to most Americans who do not know or love ice hockey. But I'm sure most every Canadian knows who Ted Lindsay, a native son, was.

Ted Lindsay

Ted LindsayI still remember that face. The over-abundant scars, the result of run-ins with fists and hockey sticks and perhaps skate blades as well. I'm sure Ted Lindsay had seen the astonished look I had on my face hundreds, maybe thousands of times. He probably counted on it as a player.

This was a face that a child might imagine the bogeyman having, who might spirit the child away from his home in the middle of the night. Suddenly, "There's no such thing as the bogeyman" lost all its meaning. There he was.

Published on February 08, 2020 05:53

Who's afraid of the bogeyman?

I went to Cranbrook School, a private boys school in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, starting in 1958.

I played sports, football and baseball. Cranbrook had an ice hockey team, but since I couldn't skate well, I never considered trying out for the team. I didn't know much about the sport.

I had a good friend at the school who was on the team, though, and I used to go to the school's rink, which was outside, to watch him practice. I would stand at one end and watch him sail around the rink on skates. He looked so graceful. One time, I noticed a grown man skating with the players. He wasn't the coach. I asked my friend who he was.

"Ted Lindsay," he said. "He helps out coaching from time to time."

Who was Ted Lindsay?

"He used to play for the Red Wings. Want to meet him?"

He meant the Detroit Red Wings. One of the six—at the time—National Hockey League teams. A little later my friend skated over with the man. He introduced me. The man did not smile. He didn't exactly have a scowl, but he looked deadly serious. I learned later he had recently retired.

Then I noticed his face. It was unlike any face I'd ever seen. It was marked with countless jagged scars. They covered the landscape of his face. It was if his face were an abstract painting. There didn't seem to be one portion of it that wasn't marked by scars moving in all directions. I probably gasped. He was fearsome-looking. The fact that he didn't smile added to his fearsomeness. Later, I read that Lindsay had over 700 stitches on that face. A journalist wrote that Lindsay had a face "that could hold three days of rain."

Ted Lindsay had played left wing on a storied line that included the legendary Gordie Howe, Wayne Gretsky's idol. He was called "Terrible Ted" by the press for his ferocity as a player. "I had no friends on the ice," he once said. He will be unknown to most Americans who do not know or love ice hockey. But I'm sure most every Canadian knows who Ted Lindsay, a native son, was.

Ted Lindsay

Ted Lindsay

I still remember that face. The over-abundant scars, the result of run-ins with fists and hockey sticks and perhaps skate blades as well. I'm sure Ted Lindsay had seen the astonished look I had on my face hundreds, maybe thousands of times. He probably counted on it as a player.

This was a face that a child might imagine the bogeyman having, who might spirit the child away from his home in the middle of the night. Suddenly, "There's no such thing as the bogeyman" lost all its meaning. There he was.

I played sports, football and baseball. Cranbrook had an ice hockey team, but since I couldn't skate well, I never considered trying out for the team. I didn't know much about the sport.

I had a good friend at the school who was on the team, though, and I used to go to the school's rink, which was outside, to watch him practice. I would stand at one end and watch him sail around the rink on skates. He looked so graceful. One time, I noticed a grown man skating with the players. He wasn't the coach. I asked my friend who he was.

"Ted Lindsay," he said. "He helps out coaching from time to time."

Who was Ted Lindsay?

"He used to play for the Red Wings. Want to meet him?"

He meant the Detroit Red Wings. One of the six—at the time—National Hockey League teams. A little later my friend skated over with the man. He introduced me. The man did not smile. He didn't exactly have a scowl, but he looked deadly serious. I learned later he had recently retired.

Then I noticed his face. It was unlike any face I'd ever seen. It was marked with countless jagged scars. They covered the landscape of his face. It was if his face were an abstract painting. There didn't seem to be one portion of it that wasn't marked by scars moving in all directions. I probably gasped. He was fearsome-looking. The fact that he didn't smile added to his fearsomeness. Later, I read that Lindsay had over 700 stitches on that face. A journalist wrote that Lindsay had a face "that could hold three days of rain."

Ted Lindsay had played left wing on a storied line that included the legendary Gordie Howe, Wayne Gretsky's idol. He was called "Terrible Ted" by the press for his ferocity as a player. "I had no friends on the ice," he once said. He will be unknown to most Americans who do not know or love ice hockey. But I'm sure most every Canadian knows who Ted Lindsay, a native son, was.

Ted Lindsay

Ted LindsayI still remember that face. The over-abundant scars, the result of run-ins with fists and hockey sticks and perhaps skate blades as well. I'm sure Ted Lindsay had seen the astonished look I had on my face hundreds, maybe thousands of times. He probably counted on it as a player.

This was a face that a child might imagine the bogeyman having, who might spirit the child away from his home in the middle of the night. Suddenly, "There's no such thing as the bogeyman" lost all its meaning. There he was.

Published on February 08, 2020 05:53

January 31, 2020

Final cut

One of the profound changes wrought by aging is how much sustenance I take from memories. At 74, I live off them like oxygen. I breathe them in and out.

Memory evokes joy and melancholy, of a life more lived than will be lived. The difference becomes more striking every day. Those long-gone times are set. I look at them as old home movies, wishing I could change the action or the script, the ending, but time, the Director, won't have it.

In New York, where I lived for 35 years, every block, every street even, elicits ghosts and echoes, a catalyst for some reverie in my mind of things done and, worse, things not done.

I am attending in my mind a retrospective of my life’s work. It's sobering.

A walk down Greene Street in New York’s Soho is a walk down two streets. The first is the Greene Street of today. Underneath, covered over by time, revealed like the paleontologist’s brush, is the Greene Street of 1979, of forty years ago, that I knew so well. In those days, as a young man, I would walk from my apartment in Greenwich Village to a loft at 55 Greene Street for my weekly writers group meeting. The film shows a single evening, in summer. I’m standing outside the door at 55 Greene. There is no bell to the illegal loft my friend is living in. I shout up to the window. It opens, a hand extends with a key, lets it fall. I pick it up, use it to open the large steel door and then walk up a flight of very wide stairs to the loft. Inside, eager young writers await.

I see that young man going to meet with his fellow aspiring writers, to put his writing into their hands and have them put their writing into his. Back then, all of us were subsisting on a strict regimen of dreams, fueled by the most open and hopeful part of us. If only I'd written more.

Today, these people are all scattered to the four winds. One is dead.

When I walk down East Tenth Street, I walk into joy and failure. At 110, between Second and Third, where I lived for four years, I watch that young man, and I tell him: be more trusting of that woman you’re living with. She loves you and believes in you. Don’t discard her love. Be braver. Give your heart to her.

The young man I was doesn’t listen.

I replay the cinema of the past. There is hardly a place or situation where I wouldn’t want a second take. Or a third. But all the films of my life were shot in one take. There were no second takes. There never are. “Good enough!” says the Director. “Print it.”

“But…” I protest.

“Next shot,” the Director says.

Then he turns to me. “One take,” he says calmly. “It's in the contract.”

Memory evokes joy and melancholy, of a life more lived than will be lived. The difference becomes more striking every day. Those long-gone times are set. I look at them as old home movies, wishing I could change the action or the script, the ending, but time, the Director, won't have it.

In New York, where I lived for 35 years, every block, every street even, elicits ghosts and echoes, a catalyst for some reverie in my mind of things done and, worse, things not done.

I am attending in my mind a retrospective of my life’s work. It's sobering.

A walk down Greene Street in New York’s Soho is a walk down two streets. The first is the Greene Street of today. Underneath, covered over by time, revealed like the paleontologist’s brush, is the Greene Street of 1979, of forty years ago, that I knew so well. In those days, as a young man, I would walk from my apartment in Greenwich Village to a loft at 55 Greene Street for my weekly writers group meeting. The film shows a single evening, in summer. I’m standing outside the door at 55 Greene. There is no bell to the illegal loft my friend is living in. I shout up to the window. It opens, a hand extends with a key, lets it fall. I pick it up, use it to open the large steel door and then walk up a flight of very wide stairs to the loft. Inside, eager young writers await.

I see that young man going to meet with his fellow aspiring writers, to put his writing into their hands and have them put their writing into his. Back then, all of us were subsisting on a strict regimen of dreams, fueled by the most open and hopeful part of us. If only I'd written more.

Today, these people are all scattered to the four winds. One is dead.

When I walk down East Tenth Street, I walk into joy and failure. At 110, between Second and Third, where I lived for four years, I watch that young man, and I tell him: be more trusting of that woman you’re living with. She loves you and believes in you. Don’t discard her love. Be braver. Give your heart to her.

The young man I was doesn’t listen.

I replay the cinema of the past. There is hardly a place or situation where I wouldn’t want a second take. Or a third. But all the films of my life were shot in one take. There were no second takes. There never are. “Good enough!” says the Director. “Print it.”

“But…” I protest.

“Next shot,” the Director says.

Then he turns to me. “One take,” he says calmly. “It's in the contract.”

Published on January 31, 2020 05:28

January 27, 2020

Final cut

One of the profound changes wrought by aging is how much sustenance I take from memories. At 74, I live off them like oxygen. I breathe them in and out.

In New York, where I lived for 35 years, every block, every street even, elicits ghosts and echoes, a catalyst for some reverie in my mind of things done and, worse, things not done. I reach out to the memories, the past dramas, of moments lived. My hand can’t grasp them.

The power of memory is confusing, evokes joy and melancholy, of a life more lived than will be lived. The difference becomes more striking every day. Those long-gone times are set. I look at them as old home movies, wishing I could change the action or the script, the ending, but time, the Director, won't have it.

I am attending in my mind a retrospective of my life’s work. It's sobering.

A walk down Greene Street in New York’s Soho is a walk down two streets. The first is the Greene Street of today. Underneath, covered over by time, revealed like the paleontologist’s brush, is the Greene Street of 1979, of forty years ago, that I knew so well. I see it, like a fossil in relief, the lives lived before. In those days as a young man, I would walk from my apartment in Greenwich Village to go to a loft at 55 Greene Street for a weekly Writers Group meeting. In my mind’s camera, I travel back in time to a single evening, in summer. I’m standing outside the door at 55 Greene. There is no bell to the illegal loft my friend is living in. I shout up to the window. The window opens, a hand extends with a key, lets it loose. It falls, and I pick it off the ground, use it to open the large, steel door and then walk up a flight of very wide stairs to the loft. Inside, eager young writers await.

I travel through time to encounter that young man, open and hopeful, to meet with his fellow aspiring writers, to put his writing into their hands and have them put their writing into his. Back then, all of us are subsisting on a strict regimen of dreams and hopes and on the wildest energy fired by the most precious part of us. If only I'd written more.

Today, these people are all scattered to the four winds. One is dead.

The two Greene Streets, one placed over the other like film transparencies, do not precisely match. They are not identical. Close enough, though, thankfully.

When I walk down East Tenth Street, I walk into joy and failure. At 110, between Second and Third, where I lived for four years, I conjure that young man, and I tell him: be more trusting of that woman you’re living with. She loves you and believes in you. Don’t discard her love. Be braver. Give your heart to her.

The young man I was doesn’t listen.

I replay the cinema of the past. There is hardly a place or situation where I wouldn’t want a second take. Or a third. But all the films of my life were shot in one take. There were no second takes. There never are. “Good enough!” says the Director. “Print it.”

“But…” I protest.

“Next shot,” the Director says.

Then he turns to me. “I have final cut," he says calmly. "It's in the contract.”

In New York, where I lived for 35 years, every block, every street even, elicits ghosts and echoes, a catalyst for some reverie in my mind of things done and, worse, things not done. I reach out to the memories, the past dramas, of moments lived. My hand can’t grasp them.

The power of memory is confusing, evokes joy and melancholy, of a life more lived than will be lived. The difference becomes more striking every day. Those long-gone times are set. I look at them as old home movies, wishing I could change the action or the script, the ending, but time, the Director, won't have it.

I am attending in my mind a retrospective of my life’s work. It's sobering.

A walk down Greene Street in New York’s Soho is a walk down two streets. The first is the Greene Street of today. Underneath, covered over by time, revealed like the paleontologist’s brush, is the Greene Street of 1979, of forty years ago, that I knew so well. I see it, like a fossil in relief, the lives lived before. In those days as a young man, I would walk from my apartment in Greenwich Village to go to a loft at 55 Greene Street for a weekly Writers Group meeting. In my mind’s camera, I travel back in time to a single evening, in summer. I’m standing outside the door at 55 Greene. There is no bell to the illegal loft my friend is living in. I shout up to the window. The window opens, a hand extends with a key, lets it loose. It falls, and I pick it off the ground, use it to open the large, steel door and then walk up a flight of very wide stairs to the loft. Inside, eager young writers await.

I travel through time to encounter that young man, open and hopeful, to meet with his fellow aspiring writers, to put his writing into their hands and have them put their writing into his. Back then, all of us are subsisting on a strict regimen of dreams and hopes and on the wildest energy fired by the most precious part of us. If only I'd written more.

Today, these people are all scattered to the four winds. One is dead.

The two Greene Streets, one placed over the other like film transparencies, do not precisely match. They are not identical. Close enough, though, thankfully.

When I walk down East Tenth Street, I walk into joy and failure. At 110, between Second and Third, where I lived for four years, I conjure that young man, and I tell him: be more trusting of that woman you’re living with. She loves you and believes in you. Don’t discard her love. Be braver. Give your heart to her.

The young man I was doesn’t listen.

I replay the cinema of the past. There is hardly a place or situation where I wouldn’t want a second take. Or a third. But all the films of my life were shot in one take. There were no second takes. There never are. “Good enough!” says the Director. “Print it.”

“But…” I protest.

“Next shot,” the Director says.

Then he turns to me. “I have final cut," he says calmly. "It's in the contract.”

Published on January 27, 2020 03:57

January 22, 2020

Therapy

I've been in therapy, on and off, since the Cold War era.

I don't know how many therapists I've seen. I would guess close to fifteen. That sounds slutty. But that's the way it was. Each time, there was a good reason. I was with a few therapists for quite a long time. The longest, in New York City, a woman, around nine years. She was expensive. They all are, aren't they, but in New York, particularly so. They almost have to be to maintain their collective reputation. I used to joke about the woman I saw for so long. I would say that one day walking by the Hudson River, I saw her in a big sailboat. The boat was named, Thank You, Rich.

I can hear them now. "How does that makes you feel?"

The first therapist I saw rescued me. I know you've heard this before. You may have even said it before. But fact is, he did. I was in college, down, down, down. Possessed by demons. (I've thought, from time to time, that an exorcism might not be a bad idea.) A friend recommended this man. I was terribly nervous. He was a classic Freudian. Lie down on the couch, facing away. Whoa. But I told him things that had been securely locked up inside, labeled, "Warning! Lethal, Disgusting, Only Me, Shameful, Do Not Repeat." And lo--he didn't call the police. He made me feel--human.

The therapists I've seen through the years haven't all been of the same quality. But you could say that of car mechanics, plumbers or dentists, couldn't you? Some I've seen briefly, to give me a new set of crampons to help climb a particularly slippery slope. Then I'm off. Some have been humorless. Always a bad sign. Some have been brilliant. Some have been less than professional. One cancelled appointments on a regular basis, not that good for the self-esteem. Onward.

As the very wise poet, Molly Peacock, said to me once about seeing a therapist, "I need backup!" Indeed. Molly wrote a tender and loving book of poems about her therapist, The Analyst. I guess this blog post will have to do for all mine.

I'm seeing a therapist now. He's my backup. And a good one. He laughs at my jokes. What's better than that? After a lifetime of therapy, I've come to understand that I can't heal some of the wounds I had hoped to heal. They are too profound. But I can become more aware, can hurt less, can do a bit better as a human.

So, all of you, every one of you, gather around. Group hug.

I don't know how many therapists I've seen. I would guess close to fifteen. That sounds slutty. But that's the way it was. Each time, there was a good reason. I was with a few therapists for quite a long time. The longest, in New York City, a woman, around nine years. She was expensive. They all are, aren't they, but in New York, particularly so. They almost have to be to maintain their collective reputation. I used to joke about the woman I saw for so long. I would say that one day walking by the Hudson River, I saw her in a big sailboat. The boat was named, Thank You, Rich.

I can hear them now. "How does that makes you feel?"

The first therapist I saw rescued me. I know you've heard this before. You may have even said it before. But fact is, he did. I was in college, down, down, down. Possessed by demons. (I've thought, from time to time, that an exorcism might not be a bad idea.) A friend recommended this man. I was terribly nervous. He was a classic Freudian. Lie down on the couch, facing away. Whoa. But I told him things that had been securely locked up inside, labeled, "Warning! Lethal, Disgusting, Only Me, Shameful, Do Not Repeat." And lo--he didn't call the police. He made me feel--human.

The therapists I've seen through the years haven't all been of the same quality. But you could say that of car mechanics, plumbers or dentists, couldn't you? Some I've seen briefly, to give me a new set of crampons to help climb a particularly slippery slope. Then I'm off. Some have been humorless. Always a bad sign. Some have been brilliant. Some have been less than professional. One cancelled appointments on a regular basis, not that good for the self-esteem. Onward.

As the very wise poet, Molly Peacock, said to me once about seeing a therapist, "I need backup!" Indeed. Molly wrote a tender and loving book of poems about her therapist, The Analyst. I guess this blog post will have to do for all mine.

I'm seeing a therapist now. He's my backup. And a good one. He laughs at my jokes. What's better than that? After a lifetime of therapy, I've come to understand that I can't heal some of the wounds I had hoped to heal. They are too profound. But I can become more aware, can hurt less, can do a bit better as a human.

So, all of you, every one of you, gather around. Group hug.

Published on January 22, 2020 04:45

January 14, 2020

Black writer, white reader

We've all seen interviews with authors where they're asked what writers have influenced them.

Sometimes the answers are surprising, most often not. I've seen very few interviews with white writers in which they say that one or more black writers influenced them. A few--not many.

Have you? If so, let me know.

Black writers sure have influenced me.

Now, it would be lovely if, as the late African American poet, Robert Hayden, said, "There is no such thing as Black literature. There's good literature and bad. And that's all." That's the way it should be. That's not the way it is. If not, why would Charles Johnson, author of Middle Passage, write, in his book, Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing, “Since the 1960s whites dare not speak on black subjects, regardless of how much research they may have done, because they lack ‘the authority of experience’ that comes from being born and raised black.”

I can't solve that problem.

I can talk about what African American writers have changed me.

I could start with Lawd Today! and Black Boy by Richard Wright.

Followed closely by:

The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. The Big Sea, the Simple books and the poetry of Langston Hughes. Up from Slavery by Booker T. Washington. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The Color Purple by Alice Walker.

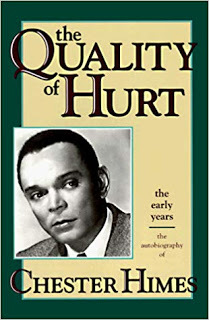

The Quality of Hurt by Chester Himes. The Sixteenth Round by Ruben "Hurricane" Carter. Beneath the Underdog by Charles Mingus. The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois. The Blue Devils of Nada by Albert Murray. Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin. An American Story by Debra Dickerson. Jamaica Kincaid's garden writing. Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver.

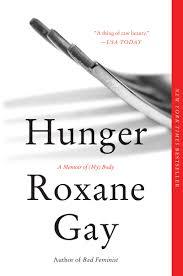

Recently, let me add Hunger by Roxane Gay. We Cast a Shadow by--ahem, friend--Maurice Carlos Ruffin. Heavy by Kiese Laymon. Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

And a whole sub-genre of books that might not appear on anyone's favorite books list, but do on mine. Including Pimp: The Story of My Life and Mama Black Widow by Iceberg Slim. Invisible Life by E. Lynn Harris. And Succeeding Against the Odds: The Autobiography of a Great American Businessman by John H. Johnson.

Yes, left many out, but this shouldn't just be a compilation, now should it?

In fact, the how and why of the influence will have to come with part II. But I wouldn't be the writer, or person, I am without having read these black writers.

Let me close with a quote from Toni Morrison's (can't forget her) 1992 book, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, "It is interesting, not surprising, that the arbiters of critical power in American literature seem to take pleasure in, indeed relish, their ignorance of African-American texts."

White writers, say it ain't so.

Sometimes the answers are surprising, most often not. I've seen very few interviews with white writers in which they say that one or more black writers influenced them. A few--not many.

Have you? If so, let me know.

Black writers sure have influenced me.

Now, it would be lovely if, as the late African American poet, Robert Hayden, said, "There is no such thing as Black literature. There's good literature and bad. And that's all." That's the way it should be. That's not the way it is. If not, why would Charles Johnson, author of Middle Passage, write, in his book, Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing, “Since the 1960s whites dare not speak on black subjects, regardless of how much research they may have done, because they lack ‘the authority of experience’ that comes from being born and raised black.”

I can't solve that problem.

I can talk about what African American writers have changed me.

I could start with Lawd Today! and Black Boy by Richard Wright.

Followed closely by:

The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. The Big Sea, the Simple books and the poetry of Langston Hughes. Up from Slavery by Booker T. Washington. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The Color Purple by Alice Walker.

The Quality of Hurt by Chester Himes. The Sixteenth Round by Ruben "Hurricane" Carter. Beneath the Underdog by Charles Mingus. The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois. The Blue Devils of Nada by Albert Murray. Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin. An American Story by Debra Dickerson. Jamaica Kincaid's garden writing. Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver.

Recently, let me add Hunger by Roxane Gay. We Cast a Shadow by--ahem, friend--Maurice Carlos Ruffin. Heavy by Kiese Laymon. Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

And a whole sub-genre of books that might not appear on anyone's favorite books list, but do on mine. Including Pimp: The Story of My Life and Mama Black Widow by Iceberg Slim. Invisible Life by E. Lynn Harris. And Succeeding Against the Odds: The Autobiography of a Great American Businessman by John H. Johnson.

Yes, left many out, but this shouldn't just be a compilation, now should it?

In fact, the how and why of the influence will have to come with part II. But I wouldn't be the writer, or person, I am without having read these black writers.

Let me close with a quote from Toni Morrison's (can't forget her) 1992 book, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, "It is interesting, not surprising, that the arbiters of critical power in American literature seem to take pleasure in, indeed relish, their ignorance of African-American texts."

White writers, say it ain't so.

Published on January 14, 2020 08:23

January 12, 2020

Books? Yes, we have books.

In the 1960 movie, The Time Machine, there's a memorable scene.

The hero, played by Rod Taylor, is an inventor who lives in late nineteenth century London. He has built a time machine. He uses it to journey 800,000 years into the future where he finds a world in which, at first glance, everything is a kind of paradise. The people are docile and seemingly happy, wearing Roman-toga-like clothes and doing, basically, nothing. Worry doesn't exist. Strangely, all their food, in the form of oversized fruit, is provided for them. By whom?

Taylor, fascinated and curious, seeks to find out more about these people, called the Eloi. His questions are answered indifferently, in the most monosyllabic way: "What kind of government rules your world?" Taylor asks. "We have no government," an Eloi responds.

"Do you have books?" Taylor asks excitedly.

"Books? Yes, we have books." replies another Eloi.

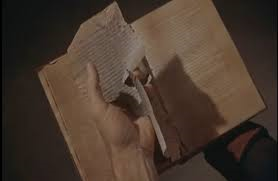

The Eloi leads Taylor to an ancient library. The place looks like Miss Havisham's house--ratty curtains, dust everywhere. The Eloi points to a shelf of books. Excitedly, Taylor pulls out a book. At last, he will find out about this "civilization." He opens the book, and it crumbles in his hand. So does the next book. He sweeps his hand across a row of books on the shelf, and they all disintegrate. (The whole scene is fantastic. Check it out here.)

The Eloi, he realizes, are mindless. Worse, they don't care.

When I saw this movie the year it came out, I viewed it as science fiction. I've never been attracted to that genre, but now I see that H.G. Wells, who wrote the book, was a seer.

With the advent of the electronic age, with Kindle, tablets, smart phones, etc., books as actual artifacts are becoming less viable. Walk onto any bus or subway, and see how many people are reading actual books versus reading from a device of some kind. Libraries are buying less and less books, more electronic subscriptions.

I led a panel at a literary conference a few years ago in which an editor--yes, an editor--said that books had had a good run, but that run was over.

Is he right? Will some Rod Taylor of the future walk into the Library of Congress and ask someone there, "Do you have books?"

And will that person say, "Books? Yes, we have books."

The hero, played by Rod Taylor, is an inventor who lives in late nineteenth century London. He has built a time machine. He uses it to journey 800,000 years into the future where he finds a world in which, at first glance, everything is a kind of paradise. The people are docile and seemingly happy, wearing Roman-toga-like clothes and doing, basically, nothing. Worry doesn't exist. Strangely, all their food, in the form of oversized fruit, is provided for them. By whom?

Taylor, fascinated and curious, seeks to find out more about these people, called the Eloi. His questions are answered indifferently, in the most monosyllabic way: "What kind of government rules your world?" Taylor asks. "We have no government," an Eloi responds.

"Do you have books?" Taylor asks excitedly.

"Books? Yes, we have books." replies another Eloi.

The Eloi leads Taylor to an ancient library. The place looks like Miss Havisham's house--ratty curtains, dust everywhere. The Eloi points to a shelf of books. Excitedly, Taylor pulls out a book. At last, he will find out about this "civilization." He opens the book, and it crumbles in his hand. So does the next book. He sweeps his hand across a row of books on the shelf, and they all disintegrate. (The whole scene is fantastic. Check it out here.)

The Eloi, he realizes, are mindless. Worse, they don't care.

When I saw this movie the year it came out, I viewed it as science fiction. I've never been attracted to that genre, but now I see that H.G. Wells, who wrote the book, was a seer.

With the advent of the electronic age, with Kindle, tablets, smart phones, etc., books as actual artifacts are becoming less viable. Walk onto any bus or subway, and see how many people are reading actual books versus reading from a device of some kind. Libraries are buying less and less books, more electronic subscriptions.

I led a panel at a literary conference a few years ago in which an editor--yes, an editor--said that books had had a good run, but that run was over.

Is he right? Will some Rod Taylor of the future walk into the Library of Congress and ask someone there, "Do you have books?"

And will that person say, "Books? Yes, we have books."

Published on January 12, 2020 05:04