Andy Wolverton's Blog, page 6

June 8, 2023

It's That Time Again... The 2023 Classic Film Reading Challenge

Love classic movies? Of course you do, otherwise you wouldn't be reading this post. Love reading? Same. So here's a way you can enjoy both, avoid bad air quality (as long as you stay inside), and possibly win a nifty prize. Join me in signing up for my friend Raquel Stecher's 2023 Classic Film Reading Challenge!

Just click the link to find out everything you need to know and get started. You've got from May 25 to September 15, 2023, plenty of time to knock out a few books on classic film. Not sure what qualifies as a classic film book? It's all on the Classic Film Reading Challenge page.

Okay, let's get this thing started! Happy reading!

June 6, 2023

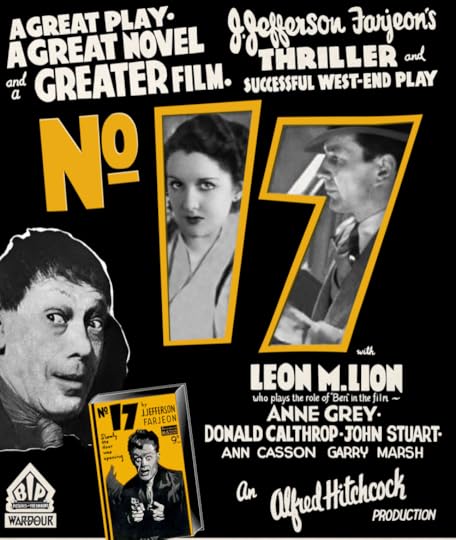

The Alfred Hitchcock Project #15: Number Seventeen (1932)*

Number Seventeen (1932)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Produced by John Maxwell (6-14)

Written by Alfred Hitchcock, Alma Reville (11-14), Rodney Ackland

Based on the play (and later novel) Number Seventeen (1925) by Joseph Jefferson Farjeon

Cinematography by Jack Cox (12-14), Bryan Langley

Edited by A.C. Hammond

Music by Adolph Hallis

Production company - Associated British Picture Corporation (formerly British International Pictures, which appears in the credits)

Distributed by Wardour Films

(1:04) Kino Lorber Blu-ray

You can find my journey (so far) through Hitchcock’s filmography ,here.

Alfred Hitchcock called Number Seventeen a disaster.

The picture was assigned to Hitchcock by Elstree Studios as a “quota” picture, films that were 100% produced in Great Britain with British casts and crew that could be imported to America. Hitchcock was hoping to be given John Van Druten’s play London Wall (1931) to adapt but was instead handed Number Seventeen, an old dark house play written by Joseph Jefferson Farjeon. In protest Hitchcock apparently decided to turn the project into a parody. Yet this idea has been disputed since the play itself contains several elements of farce. (Interestingly, The Old Dark House directed by James Whale came out the same year as Number Seventeen.)

Number Seventeen opens with a tracking shot presenting strong gusts of wind not only scattering leaves along a nighttime London street, but also blowing a man’s hat onto the doorstep of a darkened house. The man (John Stuart) follows his hat to the mysterious dwelling marked “For Sale or Let,” a structure also designated with the number 17 in an upper window.

Noticing a light above and shadows from someone moving around upstairs, the man enters to find two men at the top of the stairs: one dead and one living, a homeless drifter named Ben (Leon M. Lion) who’s very much alive, talking, and agitated. Although he claims he didn’t murder anyone, we know Ben has something to hide and so does the man chasing his hat, who now introduces himself as Fordyce.

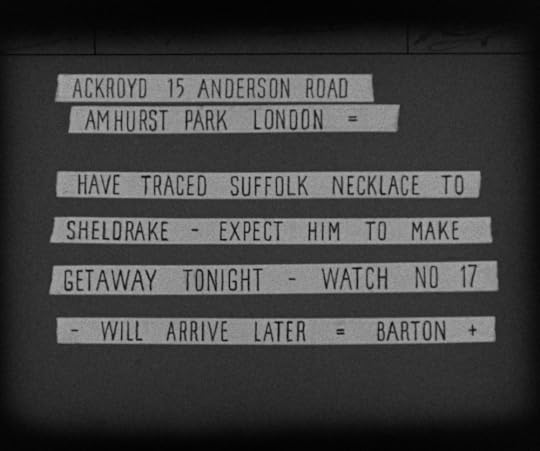

It’s not long before we have more company arriving, a young woman who enters in an unorthodox manner by falling through the roof. After dusting herself off, Rose Ackroyd (Ann Casson) claims she was on the roof of her home, number 15, searching for her missing father. Rose also shows Fordyce a telegram that mentions Number 17 and a missing necklace.

Hmmm…

After this round of introductions, the three discover that the corpse has vanished.

Oh, but there’s more. Three additional characters enter - a man named Brant (Donald Calthrop), his deaf-mute escort Nora (Anne Grey), and a man named Henry Doyle (Barry Jones), all here under the pretense of possibly purchasing the property. (Sure, I’m sure any realtor is willing to meet you at midnight.) And then a man named Sheldrake (Garry Marsh) shows up.

Put simply, Number Seventeen is a mess. But Hitchcock’s opening is intriguing and atmospheric, making good use of quick (although not very smooth) edits, shadow play, and what appears to be hand-held camera shots. We aren’t sure who any of these characters really are, what their purpose is, or what it’s all about, but confusion and intrigue are sometimes marks of Hitchcock’s work. Events happen seemingly at random and as a consequence, few of the picture’s twists are satisfying. Yet the film’s major problem is that the audience has no idea whose story this is.

It’s a given that everyone is lying about something (and maybe everything), but the script never allows any of these characters to develop. (Making things more complicated, some of them change identities.) Again, some confusion is acceptable, but there comes a point in any standard narrative in which the audience has to ask themselves, “How much longer until I know where I stand with this film?” When you watch a mystery or a thriller, the audience has to have some idea where things are headed, even if that particular direction is a deceptive one. If after a half hour (of a 64-minute movie) you don’t know who these people are and what they want, the viewing experience no longer becomes entertainment but frustration.

Yet the film is not without interest.

As mentioned before, Number Seventeen shows a Hitchcock who is more than willing to play around with quick cuts, experiment with light and shadow, and even create some wild fight scenes. Although these brawls are messy and a bit ridiculous, one brief moment brought to mind Leonard (Martin Landau) getting decked by Phillip Vandamm (James Mason) in North by Northwest (1959). Plus the claustrophobic nature of the setting works well.

The discovery of a body whose murder we have not witnessed is also intriguing. As far as I can tell (and I have seen all but seven of Hitchcock’s films), it’s rare that we see a corpse and have no idea how the murder was committed or by whom**. The only other instance I can think of in Hitchcock’s filmography is The Trouble with Harry (1955), but if I’ve missed one, please let me know.

Some of the film’s comedic elements work fairly well, but Leon M. Lion’s schtick becomes tiresome quickly. Apparently Hitchcock thought the same thing. Lion also starred in the original stage play, and Hitchcock may have had no say in casting him.

If the film is remembered at all it is usually for the final chase sequence involving a train, a bus, and a ferry. Modern audiences can easily spot the use of models, sets, and other trickery, but Hitchcock makes it work for the most part. Look at how some of Hitchcock’s more memorable suspense scenes are edited, such as the wine cellar in Notorious (1946), the bell tower in Vertigo (1958), the crop dusting scene in North by Northwest (1959), and the masterful shower scene from Psycho (1960), just to name a few. Compared to these, Number Seventeen simply shows Hitchcock playing in the sandbox.

But this brings up another point: If Hitchcock didn’t want to make this film, did he use it as an opportunity to experiment? Was he simply trying things out to see what worked and what didn’t? If so, what did he learn?

I believe that Hitchcock, like any great artist, allowed himself to learn from experimentation, remembering what worked, what didn’t, and how he could refine some of the blunt tools he used in this film, sharpening them to a fine point of precision. Audience would enjoy seeing those tools and Hitchcock’s skill over the coming decades. So for that, we can all be thankful for Number Seventeen.

And we have a MacGuffin in the form of the necklace.

If you pick up the Kino Lorber Blu-ray (and despite my review, you should) you’ll also find an audio commentary by film historian Peter Tonguette, an audio excerpt of the Truffaut/Hitchcock interview, an introduction to the film by French actor Noël Simsolo, and a one-hour documentary Alfred Hitchcock: The Early Years (2004). Plus, with the new 4K restoration, the film itself looks great. Consider picking it up.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoy my posts and would like to express your support and appreciation, you can buy me a coffee.

=============================================================

* Number Seventeen was actually Hitchcock’s 14th film to direct, but was held up in order that Rich and Strange could be released first.

** Spoiler: If you’ve seen Number Seventeen, you know that what I’ve stated here isn’t entirely accurate.

June 2, 2023

Talking About Men and Reading on Book Stew from WCTV Wilmington

I recently had the great pleasure of being a guest on WCTV Wilmington's show Book Stew with host Eileen MacDougall. We talked about men, reading, and much more. I hope you'll check it out!

May 31, 2023

The Damned Don't Cry (1950) and Caged (1950) Coming Soon to Blu-ray

Last week, anticipating yesterday's gallbladder surgery (which went very well, I can thankfully say), I made two short videos about upcoming film noir releases on Blu-ray. I'll get another video out soon about the rest of the June releases, but in the meantime, here are videos covering The Damned Don't Cry (1950) and Caged (1950). Trust me, if you love film noir, you'll want to pick up both of these!

https://youtu.be/Ybo9zHyZdc8https://youtu.be/RUCOXNW6qPwMay 29, 2023

Talking Ida Lupino, The Hitch-Hiker (1953), and more on the Cinema Chat Podcast

I was delighted to be a recent guest on the podcast Cinema Chat with David Heath, discussing The Hitch-Hiker (1953), Ida Lupino, and more!

I'm really honored to be a guest on David's show, especially since his previous guests have included Eddie Muller, Glenn Kenny, Ben Model, Joseph McBride, Kristen Lopez, Lara Gabrielle, Karen Burroughs Hansberry, Mary Mallory, Vanda Krefft, John Dileo, and many others.

You can find the podcast on various platforms, including:

Amazon Music

and more!

May 23, 2023

The Alfred Hitchcock Project #14: Rich and Strange (1931)

Rich and Strange (aka East of Shanghai, 1931*)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Produced by John Maxwell (6-13)

Written by Alfred Hitchcock, Alma Reville (11-13), Val Valentine

Based on the novel Rich and Strange (1930) by Dale Collins

Cinematography by Jack Cox (12, 13), Charles Martin

Edited by Winifred Cooper, Rene Marrison (12, 13)

Music by Adolph Hallis

Production company - British International Pictures

Distributed by Wardour Films

(1:23) Kino Lorber Blu-ray

You can find my journey (so far) through Hitchcock’s filmography ,here.

Although many of Alfred Hitchcock’s films contain dark humor, only a handful can be classified as comedies, and the success of those films is often debated. Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941) and The Trouble with Harry (1955) both have their fans, but they’re usually few in number, not very vocal, or both, yet they far outweigh those who’ve even seen Rich and Strange.

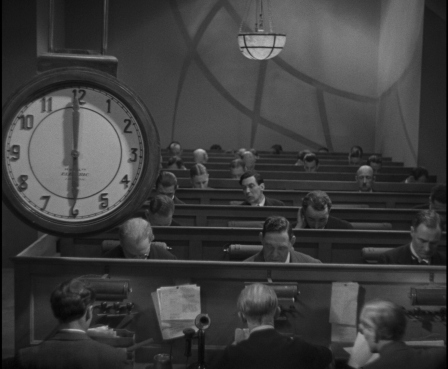

Hitchcock’s 14th film begins with a scene that calls to mind a film from just a few years later, Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), treating audiences to shots of London office workers, working stiffs being herded like cattle as they file out of their office building like robots. Perhaps the scene was influenced by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927)?

One such worker is Fred Hill (Henry Kendall), who’s shown as someone who’s clearly out of place in this environment. Hitchcock conveys this by filming Fred having problems with his umbrella amidst seemingly dozens who aren’t having any trouble whatsoever. It was probably an old gag in 1932, and while it’s not very funny, we get the point: Fred doesn’t fit in with this environment. In his mind, he was made for something better.

Fred’s wife Emily (Joan Barry) isn’t quite as frustrated with life, instead looking forward to the day when things may be different. We get the feeling that Emily is rather content with their lot, but would certainly welcome a change for the better. (Actress Joan Barry, another Hitchcock blonde, appears in this film and no other except for dubbing the voice of Alice White [Anny Ondra] in Blackmail.)

And their luck does change when Fred receives a letter from a rich uncle. Not content to wait until he’s dead, the uncle bequeathes Fred’s inheritance now so they can enjoy themselves while they’re young. With this manipulative plot device, we’re off, and so are Fred and Emily, bound for a cruise from Marseille to the Orient.

Almost instantly Fred becomes seasick and stays in their cabin. Noticing the lovely young Emily along on board, a dapper and well-known bachelor named Commander Gordon (Percy Marmont) begins to woo her. Emily initially resists, but… We know where this is going.

Of course two can play this game, and when Fred recovers, he finds himself attracted to a German “princess” (Betty Amann). Well now…

The differences in Fred and Emily come through as they both are tempted. Emily, clearly the stronger of the two, initially resists the Commander’s advances for all the right reasons: She’s married, and she loves Fred. Fred, however, rushes in blindly (and stupidly), giving us even more evidence that he’s a spoiled little boy with no depth or maturity.

Again, we know where this is going, as audiences in 1932 undoubtedly knew as well. But that doesn’t mean we can’t have a good time on this voyage.

Hitchcock gives us a wonderful scene that he used often in his career, showing us characters as they’re walking, conveying their motivation and desire. On their way to a tryst, the camera follows the legs and feet of Emily and Commander Gordon as they carefully step over a series of carelessly placed ropes and chains. Gordon steps gingerly as Emily takes care to protect her long gown. After the tryst we see the same action, but neither character practices any caution returning since the damage is done.

Hitchcock also uses a costume ball in the film, mostly to good effect, a device he would return to in Rebecca (1940), To Catch a Thief (1955), and probably others. One of the stops along the cruise finds Fred and Emily in an unnamed exotic marketplace, reminiscent of the Moroccan scenes in the 1956 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Things get darker as Fred and Emily have their inevitable confrontation with each other. Being a comedy, and watching one with 1930s eyes, we might not expect such darkness. (Certainly, even by this time, Hitchcock fans would’ve at least somewhat expected this.) Suddenly we’re in the middle of a drama without a hint of comedy. Something happens here that I will not disclose, but it’s a turning point for Fred, Emily, and everyone on board.

Near the end Hitchcock delivers a scene (no spoilers) that rivals or even surpasses many other scenes to come in subsequent films as one of the most horrific moments in his career. Even with these darker moments between Fred and Emily, the scene shocks even today, making us forget that this movie started as a comedy.

Perhaps because it is a comedy, Rich and Strange tends to get overlooked or dismissed, but it’s something of a hidden gem in Hitchcock’s filmography. Hitchcock was overall pleased with the picture, but wished he could’ve gotten actors with more box office appeal (Truffaut/Hitchcock, p. 81).

Rich and Strange, while not a great film, certainly should not be passed over. Hitchcock completists will want to at least see it if not own the Kino Lorber Blu-ray, which boasts a new 4K restoration, an audio commentary by Nick Pinkerton, and an audio excerpt from Hitchcock/Truffaut: Icon Interviews Icon.

As far as I can tell, Hitchcock does not make an on-camera appearance in Rich and Strange.

For more on the film (with spoilers), I refer you to Michael Barrett’s review at Pop Matters from 2022.

I hope you’ll join me next time. (I promise it won’t take another 18 months!)

* Originally released in the UK on December 10, 1931; in the U.S., January 1, 1932

May 20, 2023

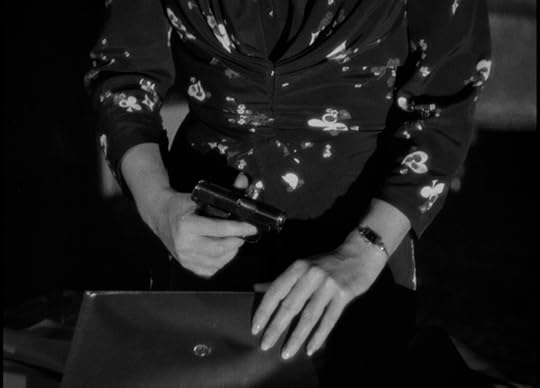

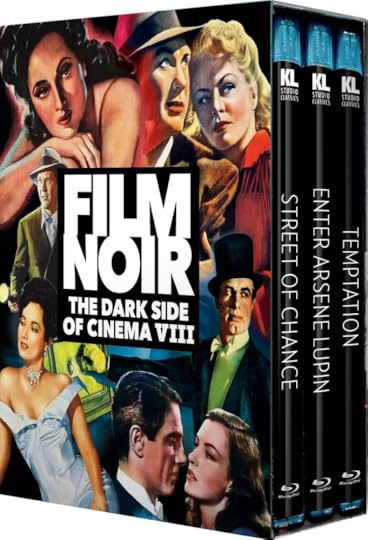

Street of Chance (1942): An Early Example of Amnesia Noir

Amnesia noir is one of my favorite subgenres, and as far as I can determine, Street of Chance (October 1942) was the second American amnesia film noir released just months behind Crossroads (July 1942). I believe Street of Chance contains more noir elements than Crossroads, not the least of which is Street’s source material, the Cornell Woolrich novel The Black Curtain (1941).

As he is walking down a New York City street, minding his own business, Frank Thompson (Burgess Meredith) is hit by a piece of falling debris from a construction site. As a result he doesn’t know who he is, how he got there, or why he’s carrying a cigarette case bearing the initials D.N.

But Frank remembers where he lives. When he encounters people from the neighborhood, some of them ask where he’s been keeping himself for the past year. Frank swears he was just there the day before. Even Frank’s wife Virginia (Louise Platt) is surprised to see him.

He’s still a little loopy, trying to fit all the pieces together, but when he sees a man (Sheldon Leonard) he assumes to be a thug following him, Frank realizes he’s in danger.

Okay, things could be worse, I guess…

But things get a little clearer - and worse - when Frank meets a woman named Ruth (Claire Trevor) who knows him as “Danny,” a man wanted for murder.

Street of Chance is an nifty amnesia noir that’s both contrived and fun, featuring some good performances, nice twists, and effective cinematography by Theodor Sparkuhl who also shot Among the Living (1941), The Glass Key (1942), and one of my favorite comedies from the 1940s, Murder, He Says (1945). In fact you could probably trace several visual amnesia tropes back to this film, largely due to Sparkuhl’s excellent work.

It’s too bad director Jack Hively isn’t nearly as imaginative as Sparkuhl. Meredith makes a nice “lost and helpless” noir protagonist, but he and the rest of the cast can’t carry the film.

Hively’s handling of Meredith’s fine performance is static and lifeless, rarely taking the opportunity to visually reflect Frank’s confusion and instability. The lack of noir atmosphere, especially when shooting interiors, creates little tension.

And the rest of the cast is quite good. I’m always glad to see Claire Trevor in any film. Sheldon Leonard is Sheldon Leonard… or is he?

Street of Chance is far from the worst entry in the Dark Side of Cinema series. If nothing else, it is clearly film noir, whereas some of the titles in the series have questionable noir status at best. If you own the Kino Lorber Dark Side of Cinema Vol. VIII set, you already have this one. The film also played on the Noir City festival circuit last year. Although the disc contains a few areas that have been well-worn, the 2K restoration mostly looks good.

Bottom line: Enjoyable.

May 18, 2023

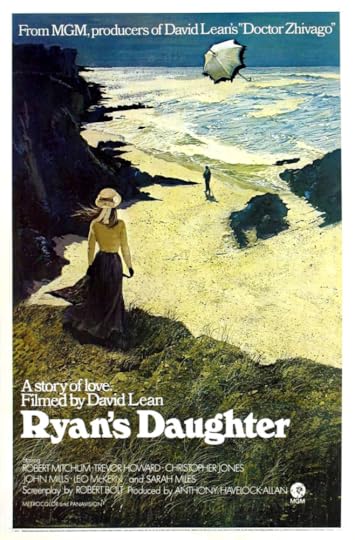

Ryan's Daughter (1970) or "David Lean... What Happened, Old Chap?"

Ryan’s Daughter joins a long list of other films from the 1960s and ‘70s that I’ve owned on DVD for years, discs that usually sit on my shelves until I discover there’s no room for new acquisitions. Before last week, I’d estimate I’d owned Ryan’s Daughter for at least two or three years.

Part of my hesitation in watching it was probably due to the fact that the film is (1) over three hours long, (2) not well-regarded by most critics and audiences, and (3) hated by many Robert Mitchum fans. But I put all those hesitations aside last week. (SPOILERS ABOUND)

Let me start by saying I’ve researched very little about Ryan’s Daughter (loosely based on Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary). I also have a long, but unusual relationship with David Lean’s films. I saw The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) on WTBS (years before we had TCM) one Saturday afternoon. I loved the film, especially the performances and the examination of a man who realizes too late he’s made a monumental mistake.

I was in college when A Passage to India was released and totally fell into the film. (I didn’t read the E.M. Forster novel until many years later.) I loved the picture, the characters, the cinematography, and the fact that Alec Guinness appeared in both.

In watching the film while it was in theaters, I knew that Lean was a director I would want to explore further. I believed he was one of the current masters who would probably be gone soon. (Indeed, A Passage to India was his final film, not counting the 1979 documentary Lost and Found: The Story of a Cook’s Anchor). I felt I was watching a work of greatness from a gifted director just before he vanished forever.

Later I saw some of Lean’s other epics such as the stunning Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago (which I didn’t really care for), and was in awe of them, especially visually. I hoped that Ryan’s Daughter might tread on familiar territory. For the record, I’ve only seen two of Lean’s films before Kwai: Brief Encounter (1945) and Great Expectations (1946), both of which are masterful. (I know, this is a problem I must correct soon.)

Back to Ryan’s Daughter…

How can you not love the Freddie Young cinematography in this film? It’s absolutely fantastic and certainly deserving of its Oscar win. There’s nothing in the look of the film that lessens my enjoyment in the least.

I can’t say that about the picture’s other aspects. The cast is a mixed bag, but that’s not totally the fault of the actors. (More on that in a moment.) Christopher Jones as the British Major Doryan is the weakest link, but at least he doesn’t have to do very much.

Even though Robert Mitchum is woefully miscast and playing as far against type as you can get, I enjoyed him in the role. It’s just so foreign to him, like asking a duck to play wide receiver. Mitchum had an awful time on the film, which you can read more about in his biography Baby, I Don’t Care by Lee Server.

Sarah Miles (nominated for an Oscar), Trevor Howard, John Mills (Oscar winner), Leo McKern, Barry Foster, and others are all mostly fine, and I’ll get into a bit more of the actors in a moment.

The Maurice Jarre score is equal parts wonderful and embarrassing. Jarre worked with Lean from Lawrence through A Passage to India, creating some stunning, sweeping musical moments that frequently complement the visuals, and this is certainly the case here in places. Yet Jarre also drops an anvil or two on our heads when he attempts to drive home the point that Mitchum’s character Charles is frustrated by Rosy’s behavior, or Thomas Ryan (McKern) is filled with anxiety about his secret. Why did Lean and Jarre think such blatant aural reminders were necessary? Did they not respect the audience enough?

The biggest disappointment for me with Ryan’s Daughter is its script. It’s all over the place. If the film is sprawling, that’s one thing. But if the film and the script are sprawling, you’ve got a long, uncontrollable mess, and if Lean enjoyed anything, it was control.

So what do we expect from a 3-hour epic? We have to know the characters, their motivations, and what they want. We get touches of this, but just brush strokes.

Mitchum’s Charles is a quiet widower largely uninterested (or unable to be interested) in sexual love. (Again, you would cast Mitchum for this role why, exactly?) He also lives a very routine and, let’s face it, boring life. (Again, you picked Mitchum for this?)

Rosy is filled with excitement and curiosity, but she’s also impatient. She’s going to stop at nothing to get what she wants (or thinks she wants).

From the get-go, Rosy is repulsed by the village idiot Michael (Mills). He sees Rosy as a thing of beauty, like the flowers he often carries. He wants to be close to that beauty, to hold it, kiss it, but Rosy is disgusted whenever Michael comes within a few feet of her. He is, as she will be as the picture progresses, shunned and laughed at by the locals. Unlike him, however, she will be not only shunned, but also scorned and hated by the community.

Michael also becomes interested in explosives, which could destroy not only him, but the entire village. He doesn’t know what he’s doing until Major Doryan shows him what even the smallest of explosives is capable of doing. Rosy also is flirting with disaster with Major Doryan, and the consequences of her acts are far more explosive to her and the community.

These are aspects of the film that don’t need to be overplayed, but could’ve been given a little more attention. I could explore these characters and how the screenplay could’ve made these connections stronger, but we also have the subplots of the hatred of the Irish locals for the occupying British, the local informer, the storm and its aftermath, Tim O’Leary (Barry Foster) and his small band of Irish Republican Brotherhood men, and the themes of waning respect for religion represented by Father Collins (Trevor Howard), the future of Ireland, and more.

But I want to now focus on a few things I noticed about this film and Lean’s next and final non-documentary film A Passage to India. (SPOILERS HERE AS WELL)

Both Rosy and A Passage to India’s Adela Quested (Judy Davis) are interested, if not obsessed, with their quests. (Quested. I see what you did there, E.M. Forster…) Rosy’s quest: to land a husband, an acceptable way to satisfy her desires, and Adela’s, to experience “the real India,” but there’s much more she wants to experience. Both women have similar features: fair skin, the same shade of brown hair, a pretense of the niceties of society. Yet while Rosy is primarily pursuing a blind passion, Adela is filled with quiet anxiety over her upcoming marriage to Ronny Heaslop (Nigel Havers), the British magistrate in Chandrapore.

It’s been years since I’ve seen A Passage to India, but there’s a scene where Adela explores a wooded area by herself. She comes upon a series of statues depicting sexuality. This scene provides an awakening in Adela that we don’t see in Rosy (at least not quite in the same way). It also prepares us for Adela’s accusation that her new friend Dr. Aziz Ahmed (Victor Bandejee) attempted to rape her inside the Marabar Caves. (Interestingly, Ryan’s Daughter has a brief shot of a cave, suggesting that Rosy and Major Doryan enjoyed a tryst there.)

That element of mystery in A Passage to India is one of the driving forces of the film. Since we, the audience, don’t get to experience that moment, we’re always wondering what really happened up to (and beyond?) the film’s ending. The elements of mystery in Ryan’s Daughter are far lesser. We may be surprised that Rosy and Charles are together at the film’s end, but how long will they be together? The biggest mystery at the conclusion is whether anyone will ever discover the identity of the village’s true informer.

Other comparisons come to mind, but I have already taken what I thought would be a short post and turned it into a length approaching Leanian proportions.

I don’t believe Lean was necessarily trying to “fix” the problems that plagued Ryan’s Daughter in making A Passage to India, but the latter film is more satisfying to me personally. In a manner of speaking, I love Ryan’s Daughter and wish it had been better. I’m sure A Passage to India has it’s problems, those I’ve forgotten or have yet to discover, but it is a film I treasure, perhaps due to when I saw it and where I was in my personal and cinematic journey. (There's a reason I call this Journeys in Darkness and Light.)

I’m sure we all have such films. Feel free to share yours. Thanks for reading.

May 12, 2023

Why Men (and Boys) Don’t Read - My MLA Presentation

Yesterday I had the great pleasure of delivering a presentation at the Maryland Library Association’s annual conference in Cambridge, Maryland at the Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay. My topic was “Why Men (and Boys) Don’t Read,” based partly on my book Men Don’t Read: The Unlikely Story of the Guys Book Club. (The book is available here, at Amazon, and the usual online places.)

(photo: Harry Brake)

Like most conferences and conventions, MLA had multiple events running at the same time as my presentation, so I was delighted and amazed to have 37 people in attendance, several of whom were my coworkers at AACPL. (Thank you all!)

Although most of my book focuses on men and reading, I spent significant time yesterday talking about the problems of boys and reading. If you want some sobering information, just Google “boys and reading” and see what you find. There are many reasons why this is a problem, but one of the issues I focused on involves a generalization (yet one that’s often true) that boys are more interested in reading about things they can use right now. That might include how to shoot more baskets, run faster, build a treehouse, play Minecraft better, or something else. Boys generally (there go those generalizations again) want to read something that’s going to pay off now, not weeks, months, or years from now.

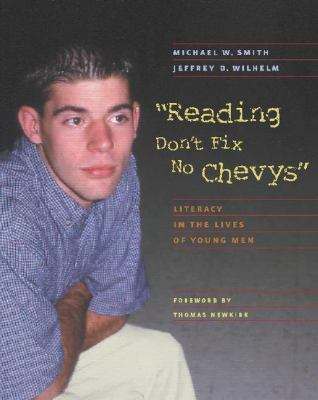

So if we can identify the activities boys like and find a way to work reading into those activities, we have a greater chance than we would if we just kept reminding them of the importance of reading. (Not a topic they're very jazzed about.) I gave several strategies for such activities, some of which I found in a book called Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys: Literacy in the Lives of Young Men (2002) by Michael Smith and Jeffrey D. Wilhelm. Although the book is over 20 years old, the information in it is still valid. (And you can find it cheap on the used market.)

But we also talked about reading for girls, men, and women. We are in a place right now (which is partly due to COVID, but we can’t totally blame this on the pandemic) where people of all ages are reading less. Oddly enough, this is a time when more books are available than ever in so many different formats. I talked about some of the reasons why reading is not generally a priority for our society and why the problem isn’t new. More importantly, I discussed what we can do about it.

I was overwhelmed at the number of people I talked with after the presentation who told me they couldn’t wait to get home and try some of these methods and techniques I discussed. I was delighted to hear this, but told them I don’t have all the answers. We all have to work together: librarians, teachers, and parents. We have to share our resources, our victories, and even our defeats. It’s a long game we’re playing here, and we have to be patient.

By the way, I attended other presentations at MLA, all of which were terrific, but the best one was led by Barb Langridge who runs A Book and a Hug, a fantastic website for helping determine a reader’s personality type, which greatly helps in recommending and choosing books for readers of any age.

My entire MLA experience was tremendous, but if there was a disappointment, it was the fact that the presentations were not recorded. Yet if you would like for me to speak to a group in your area, please let me know. You can reply here or contact me via Twitter @awolverton77. (Although my book covers some of this material, the focus on younger readers is more prominent in my in-person presentation.) Again, feel free to contact me if you’re interested.

In the meantime, keep fighting the good fight. Reading is for everyone, for all ages and all groups of people. Keep reading!

May 2, 2023

The Last Time I Wrote Fiction

For several years my main focus was becoming a fiction writer. I wrote stacks and stacks of short stories, two novels (one was bad; the other excruciatingly bad), and collected countless rejection slips. But I had successes as well. I published in a few very small magazines you've never heard of. I was chosen to attend the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop in 2004 and absolutely loved it.

But my fiction never really went anywhere.

Yesterday I was reminded that 12 years ago I had a short story published in Jenny Magazine, a magazine of the Youngstown State University Student Literary Arts Association. I was even invited, along with other writers, to read my work at an event celebrating the magazine's second issue (Fall 2011). It was a great time with great people.

This is the story that made it into that issue, "I Believe This Belongs to You," a story inspired by one of my favorite novels, Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. I hope you enjoy the story.