Andy Wolverton's Blog, page 4

September 7, 2023

Movies Are Magic: The Director's Cut (2022) Jennifer Churchill

Movies Are Magic: The Director’s Cut (2022) Jennifer Churchill, illustrated by Howard Edwards Creative, Asanka Herath

Published by Jennifer Churchill in partnership with The Film Detective

Paperback, 87 pages

Includes an introduction by Ben Mankiewicz, homeschool projects, teacher’s guide and photos

ISBN 979-8431662133

(Movies Are Magic: The Director’s Cut is an updated and expanded version of Churchill’s original Movies Are Magic from 2018.)

This book speaks to my heart. Okay, I know I’m not being very objective here, but (1) I’m a public librarian who works with children, (2) I’m a classic movie fan, (3) and the book does what it sets out to do.

Churchill’s goal is to provide “an introductory glimpse into the fascinating history of the origins of the streaming images kids watch today. It is my hope this updated edition will help bring the movies and history highlighted here even more to life.” Not only that, but Churchill also wants to celebrate the act of watching movies together with others, they way they were intended to be viewed.

From the very beginning of humanity, we have been captivated by stories made up of images, and Churchill takes us on a journey starting with the Lascaux cave paintings, moving into vaudeville, series motion photography, the Lumière brothers, silent film, and more. In writing a book about classic movies for children, one might be tempted to go either into too much detail, overwhelming the young reader, or too little, making kids wonder “What’s the point?” Movies Are Magic finds that sweet spot, focusing on many of the essential players and films that children may recognize, but more importantly are accessible, such as Charlie Chaplin, King Kong (1933), and cartoons.

Not only is the text approachable, so also are the illustrations. As with most smiley-faced emojis, the people depicted here have similar faces, easy entry points, if you will. When kids see the Chaplins, Keatons, and others onscreen, the familiar illustrations have prepared them for the unforgettable faces. And Churchill’s son Weston and his illustrated dog Oscar are adorable! Yet these graphics also allow children reading the book (or having it read to them) to place themselves into the stories as children frequently do with picture books.

To those naysayers who might counter, “Let’s get real. No kid is going to want to watch old black-and-white movies when they have all this other great stuff they can stream anytime they want,” I would challenge them to show a Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin short to any kid and ask them how they like it. You probably won’t even have to ask them how they liked it. You’ll see the smiles on their faces.

The book also does a fine job of introducing media literacy as well as discussing complex and controversial concepts. The genius of the book is that these ideas are not presented in a pedantic way, but rather organically.

Churchill also includes many fun ideas for kids and grown ups such as movie night and recipe pairings based on classic movies, classic movie and snack night ideas, how to make a zoetrope, and more.

What’s not to love about this book? It’s a must-own for people who love classic movies and want to pass that love on to their kids, grandkids, nieces and nephews, but it also provides a great way for parents who may not know much about classic movies an opportunity to discover them with their children.

My hat’s off to Churchill, Weston, and Oscar, for presenting such a fun book that can be enjoyed for years to come.

September 5, 2023

2023 Summer Reading Challenge: Suite for Barbara Loden (2012/2016) Nathalie Léger

Suite for Barbara Loden (2012/2016) Nathalie Léger, translated by Nathalie Léger and Cécile Menon

Dorothy Project

Paperback, 123 pages

ISBN 978-0-997366600

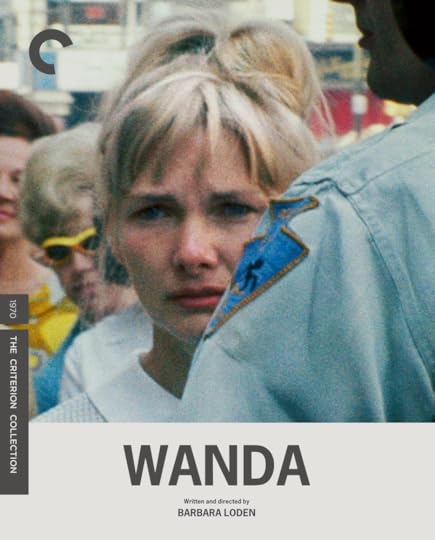

Suite for Barbara Loden would appear to be a book for a very limited audience. Other than cinephiles, how many people know who Barbara Loden was? How many have seen her only directorial effort, Wanda (1970)? Thanks to a physical media release from Criterion in 2019, the film is readily available, but even if you haven’t seen it, you can - and should - read Suite for Barbara Loden.

Richard Brody of The New Yorker famously described Loden as the “female counterpart to John Cassavetes.” She worked in theatre and early television, appeared in the films Wild River (1960) and Splendor in the Grass (1961), both directed by Elia Kazan, whom she later married. You might say that’s where Loden’s problems began, but they probably ran deeper and earlier than that.

Suite for Barbara Loden is a hybrid of sorts, part biography and part fiction, yet the reader unfamiliar with Loden and her work won’t know the difference. (I’m not sure I do, either.) The book is a portrait of a life seeking answers, or perhaps a life that has reached the point beyond seeking answers, having found none before arriving at this point. Both Barbara and Wanda seem to be women looking for acceptance and self-understanding, seeking to discover value and finding little. Léger, the narrator of the book, is on her own journey of discovery, traveling through the mining towns of Pennsylvania, tracking down archives and attempting to contact people who knew Loden.

During one of her stops in Carbondale, PA, Léger asks a local waitress at a diner how mines work. Léger’s answer:

She spoke slowly, gesturing with her hands: you dig, you shovel, you sift, you extract, sometimes you use dynamite, you shovel some more, and each new layer of coal, each new seam, is uncovered, excavated, sifted, and shoveled aside, fashioning an itinerant landscape on the vast devastated terrain. That’s what I understood - the landscape is constantly being unmade in one place and reconstructed in another, and once the seam is exhausted it gets filled in with the waste that once formed a high, dark embankment, and is abandoned for another mine.

The implication here and in other places is that Loden’s life underwent such devastating handling. It certainly pertains to Wanda’s life in the film. Yet we don’t really know exactly how much of what’s written here is autobiographical, the same way we don’t know how much Loden’s life is mirrored in Wanda’s. In both cases, I suspect quite a lot.

Suite for Barbara Loden shows us that often there are no easy answers, no objective entity which can measure the value of a person. Sometimes we are the least qualified to judge ourselves, but that doesn’t stop us from doing so. Yet Suite for Barbara Loden is more than a discovery for Léger about Loden. It’s also a discovery of who we are.

This review is part of the 2023 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge. You can (and should!) sign up here and be a part of the challenge, telling others about the classic film books you're reading, and getting suggestions for your own reading. Enjoy!

September 3, 2023

A Discussion with John Sayles

A few days ago, our Great Movies virtual discussion group was surprised and delighted to welcome special guest John Sayles, director of The Secret of Roan Inish (1994), the film we discussed to kick off the month of September. Here is that conversation! Many thanks to my friend Alison M., Andrew R., and Colin C.

September 1, 2023

The Warner Brothers (2023) Chris Yogerst

The Warner Brothers (2023) Chris Yogerst

University Press of Kentucky (part of the Screen Classics series)

Hardcover, 360 pages

ISBN 9780813198019

Includes foreword by Michael Uslan, notes, bibliography, acknowledgments, index, photos

Official release: September 5, 2023

The book’s prologue, “Put Up or Shut Up,” could have stood as the subtitle of Chris Yogerst’s new book The Warner Brothers. After early struggles, triumphs, and failures, these Polish American siblings became the first movie studio to create a feature defying the Nazi threat with Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939). It wasn’t the first time the studio portrayed society’s problems on the big screen, and it certainly would not be the last. Yet while the four Warners banded together for many victories and moments of greatness, their personal lives often caused anguish, bitterness, and great damage.

Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack Warner built their studio’s reputation by being courageous, not only in creating motion pictures portraying stories “ripped from the headlines,” they also led the way in embracing talkies, depicting an uncompromising view of the Great Depression, and, as mentioned earlier, standing up to Hitler. The brothers succeeded in spite of (or perhaps because of) their different personalities: Albert, quietly content to work away from the spotlight in distribution; Sam, “a genius whose enthusiasm for technical advancements was contagious” (p. 5); Jack, the VP in charge of production; and Harry, the president of the company, a man who watched trends, understood audiences, and was powerful enough to meet with world leaders. Most of the story - and the fireworks - belong to Jack and Harry.

While the movies that emerged from the studio are not the primary focus of the book, the major films, such as Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), Casablanca (1942), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), and many others receive plenty of attention. Yet the brothers’ behind-the-scenes efforts on those films provide narratives we perhaps haven’t heard.

Readers will find all the big stories here: censorship, stars and contract disputes (James Cagney, Olivia de Havilland, Bette Davis, etc.), battles with the U.S. Senate, the upheaval caused by WWII, the New Hollywood of the 1960s, and more. But each of these accounts takes on a different meaning when placed under the microscope of the battles raging between the brothers and their families. Prepare yourself for not only triumph, but heartbreak and tragedy. Although Warner Bros. prided itself on producing movies that addressed real issues in an uncompromising manner, some of the greatest conflict occurred within the walls of the Warner family itself.

Yogerst packs a tremendous amount of the history of the Warner Brothers and the studio into one volume, making for an informative and compelling read. Anyone with an interest in movie history, especially of the major U.S. studios, will want to add this book to their collection immediately.

August 28, 2023

September 2023 Film Noir New Releases

September is almost here, which means a new slate of film noir and neo-noir releases. I hope you find some temptations here...

August 9, 2023

New Discoveries in Rear Window (1954)

Letterboxd tells me that last night’s viewing of Rear Window (1954) was my fourth watch, but it’s probably closer to 10 or 12. Regardless of the number, I’ve seen the film enough times to know exactly what’s going to happen next, the next line, who’s going to say it, and how the other character(s) will respond. Rear Window is one of those movies that’s so familiar, not only can you watch it over and over, you can also discover something new with each viewing.

One of the things I noticed was movement, not only the motion of the characters across the way going about their daily lives (and the brilliant way Hitchcock choreographs them), but the movement in Jeff’s (James Stewart) apartment. It’s a confined space, which obviously adds to the tension, yet during at least two arguments with Lisa (Grace Kelly), Jeff expertly maneuvers his wheelchair so that he’s able to come as close to her as possible, making his points about what he believes is a murder that’s occurred in the neighborhood. It’s an instinctive move, and even in a wheelchair Jeff knows how to quickly get to Lisa and get his point across. Had he been able to stand, he would’ve towered above her. Instead, as he’s seated, she towers above him and consistently bests him. Not only this, she has the freedom of movement he lacks.

That freedom of movement also imprisons Jeff. Lisa can move freely about the apartment, getting the door for the delivery man from 21, warming up their dinner, turning on the lights, and using her body language in a variety of ways. Yet during most of the conversations concerning the future of their relationship, they are mostly on equal footing (or equal sitting, as the case may be). They are more or less at eye level with some distance between them, each making their case: she to gain acceptance into his life, he to end their relationship knowing that neither of them will ever fit into the other’s world. Hitchcock imposed so many spacial limitations upon himself and his characters, yet they all work brilliantly.

I also never noticed how difficult it is for Jeff to move about the apartment when it becomes clear that Thorwald is coming for him. There are only so many places a wheelchair can go in an apartment, and few of them make for good hiding places. The ease with which Jeff rushes to Lisa for his verbal combats are useless here. He’s never had to try and hide in his own apartment, at least not in a wheelchair. Jeff is reduced to trying to find the darkest possible corner of the dwelling in the scant time he has before the door opens. Although I’ve seen the movie several times, my anxiety level was off the charts, worrying that Jeff wouldn’t find those shadowy areas in time.

Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy)

Miss Lonelyhearts (Judith Evelyn)

I also noticed three close-ups (actually medium shots that feel like close-ups) of two women (other than Grace Kelly and Thelma Ritter). These two close-ups (not seen through Jeff’s zoom lens or binoculars) happen very quickly with two of them occurring after the discovery of the dead dog: close-ups of Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy) and Miss Lonelyhearts (Judith Evelyn). This is Hitchcock’s way of showing us that these are real people with real feelings, not just movable chess pieces in an ensemble of supporting players. Significantly they are also women dealing with real problems: Miss Torso “juggling wolves,” and Miss Lonelyhearts battling depression. (We also see a very quick close-up of Miss Lonelyhearts near the end of the film during Jeff’s struggle with Thorwald. I’d never noticed it before.)

Yet one aspect of the film had never struck me until last night. It had been obvious all the time, hiding in plain sight: Grace Kelly’s voice. Not just her voice, but her delivery, register, volume, and speed. The next time you watch Rear Window, pay close attention to her mood and how her voice matches it, especially in transitions from sweetness to confusion to anger to inquisitiveness. It’s a tremendous performance in vocal range.

I’m fortunate to live so close to a theater (Landmark Harbour Center in Annapolis, MD), which will continue Hitchcock month with the following films. Maybe I’ll see you there? (All Tuesdays at 7:30pm)

August 15 - The 39 Steps

August 22 - Rope

August 29 - The Lady Vanishes

July 30, 2023

August 2023 Film Noir New Releases

Here's what you can expect in new releases in classic film noir in August!

July 29, 2023

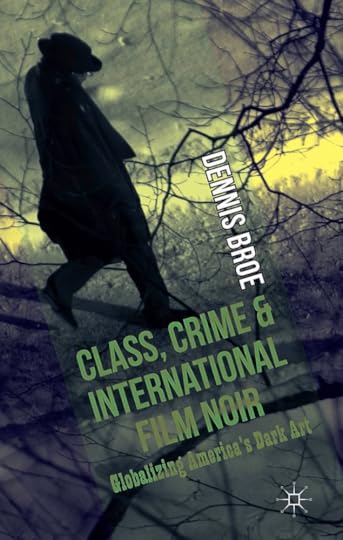

2023 Summer Reading Challenge: Class, Crime & International Film Noir (2014) Dennis Broe

Class, Crime & International Film Noir: Globalizing America’s Dark Art (2014) Dennis Broe

Palgrave Macmillan

Hardcover, 233 pages

Includes table of contents, list of figure, foreword by Kees van der Pijl, preface, acknowledgments, notes, bibliography, index, photos

ISBN 9781137290137

(Photos below are not taken from the book.)

Although the French gave us the name, many people believe film noir movies were made exclusively in America. Some even insist that noir pictures from other countries should not even be categorized as film noir. Dennis Broe’s Class, Crime & International Film Noir destroys that claim.

Broe, Professor of Media Arts at Long Island University and the author of Film Noir, American Workers and Postwar Hollywood (University Press of Florida, 2009) explores international trends that led to the birth of noir movies in France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, and the Mediterranean. Classic film noir was a global phenomenon touching on politics, economics, and aesthetics both before and after World War II. All the countries and areas represented in the book experienced significant social turmoil and change, and those elements appear in their films. The darkness of those pictures stems from a sense of defeat, powerlessness, and lack of hope that was largely economic. Yet while Broe finds common ingredients from each of these countries, he also uncovers some interesting differences.

La Bête humaine (1938)

In France, the left-wing Popular Front movement, workers’ strikes, and the rise of poetic realism in film all contributed to works such as Le jour se lève (Daybreak, 1939, Marcel Carné), Le Quai des brumes (Port of Shadows, 1938, Marcel Carné), and La Bête humaine (The Human Beast, 1938, Jean Renoir). With each chapter, Broe provides the social and economic backgrounds of the era affecting stories and character types, especially those of the working class. Jean Gabin, one of the most popular French actors of all time, excelled in such roles. Gabin, who appears in all three films, plays a fundamentally good man caught up in the forces working against him. As we would see from American film noir protagonists just a few years later, Gabin’s characters are desperate, on the run, and trapped with no way out. They’re not so concerned with winning, but surviving.

Hell Drivers (1957)

British post-war cinema gave a large working class the chance to show the reality of their lives. Shunning fantasy, stale comedies, and blue blood dramas, these noir titles conveyed the frustrations and struggles of the blue-collar world in films like Hell Drivers (1957, Cy Endfield), Night and the City (1950, Jules Dassin), and the Carol Reed masterwork The Third Man (1949). Several of these films also starred American actors whose box office popularity extended to the UK, promising not only a safer financial bet, but also an opportunity for blacklisted American directors like Endfield and Dassin to break free from the constraints of the U.S. Production Code, to say nothing of HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee).

Bitter Rice (1948)

In Italy, unemployment and inflation in the north and agitation in the agrarian south created a cinematic realism, especially after Hollywood dumped its backlog of films in the country. The dark side of neorealism in films like Ossessione (1943, Luchino Visconti), Bitter Rice (1948, Giuseppe De Santis), and others criticized political oppression, including the remaining Fascist presence, and explored Italy’s harsh economic conditions.

The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

Japanese noir runs the gamut between identity, abuse of power, repression, and much more, seen in films such as Akira Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel (1948), Stray Dog (1949), and a film containing layers of depth and corruption, The Bad Sleep Well (1960), which Broe states, gives “shape to his criticism of a society that was, as he saw it, on the brink of both prosperity and disaster” (p. 175). These three Kurosawa films are clearly powerful, but I’m surprised by the omission of High and Low (1963). Other directors and other films are mentioned, but the Kurosawa pictures provide the bulk of the chapter.

The short section on Mediterranean noir is somewhat tacked on and out of place since most of the films explored are well beyond the established era of classic film noir. While the section is interesting, it demands a more comprehensive study, which can, no doubt, be found in many other works.

Much of Class, Crime & International Film Noir is fascinating, yet readers should know that this is an academic work written primarily for academics. If you’re really into film noir, you might consider borrowing the book from a college or university library, through interlibrary loan, or wait (like I did) for a good discount to pop up, since the book (in paperback or hardcover) retails for about $55.

If nothing else, Class, Crime & International Film Noir proves that film noir was (and remains) a global phenomenon that fans should not ignore.

===============================

This review is part of the 2023 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge. You can (and should!) sign up here and be a part of the challenge, telling others about the classic film books you're reading, and getting suggestions for your own reading. Enjoy!

July 21, 2023

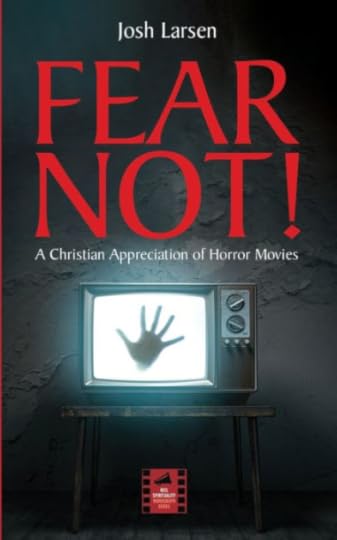

Christianity and Horror? Can Those Two Coexist? Read Fear Not! (2023) by Josh Larsen

Fear Not! A Christian Appreciation of Horror Movies (2023) Josh Larsen

Cascade Books (part of the Reel Spirituality Monograph Series)

Paperback, 106 pages

ISBN 978-1-6667-3852-0

Includes foreword by Soong-Chan Rah (Robert Munger Professor of Evangelism, Fuller Theological Seminary), acknowledgments, bibliography, index of movie titles

Josh Larsen, co-host of the WBEZ/NPR podcast Filmspotting and editor of Think Christian, a digital magazine on faith and culture, has taken on a tall order: writing about horror movies and Christianity in a way that will attract rather than repel both groups. Horror fans may gravitate to the genre for many reasons, and from my frequent examination of new movie releases on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K, horror is alive and well. Yet a significant number of Christians want nothing to do with horror, sometimes citing a passage from Philippians that Larsen uses in his introduction:

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable - if anything is excellent or praiseworthy - think about such things. (Phil. 4:8, NIV)

Is it even possible to find something noble, right, pure, lovely, excellent, or praiseworthy in films like The Shining (1980), Train to Busan (2016), The Witch (2015), Candyman (1992, 2021), Psycho (1960), Paranormal Activity (2007), and others? Larsen seems to think so, and so do I. After all, as Larsen points out, “Christianity speaks specifically to our fears,” and not only do these films speak to those fears, they frequently do so with messages of (or at least opportunities for) redemption.

Larsen understands that such an undertaking, especially in a genre so vast and voluminous, cannot realistically be contained in one volume. Yet the 66 films referenced stretch from 1931 (Dracula) to 2022 (X). Not bad for a book just over 100 pages.

Various periods of film history (especially in America under the Production Code) demanded restrictions on what could and couldn’t be shown. Aspects of violence, language, sexuality, sacrilege, and more that could only be hinted at during America’s early days of cinema are today commonplace. Larsen correctly points out that discernment is a personal matter (what offends you doesn’t necessarily offend me), yet we must be sensitive to sharing our thoughts, opinions, or the movies themselves with others who might find them uncomfortable or offensive.

Each chapter focuses on a particular subgenre of horror movies and their associated fears, such as “Zombies: Fear of Losing Our Individuality,” “Found Footage: Fear of the Dark,” “Psychological Horror: Fear of Our Anxieties,” and others. While each of the fears connected to these categories can be understood (and possibly experienced) by anyone, Larsen examines them all from a Christian worldview using the Bible as a source of illumination.

Case in point: In the chapter “Slashers: Fear of Being Alone,” Larsen makes a strong connection between power and helplessness in the 1984 Wes Craven film A Nightmare on Elm Street. Stalking Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) in the world of her dreams, Freddie Krueger (Robert Englund) takes advantage of the vulnerability of sleep to attack her, resulting in serious consequences in the waking world. Nancy asks her boyfriend Glen (Johnny Depp) to watch over her as she sleeps, but Glen can’t stay awake, leaving Krueger unopposed in his savage quest.

Readers familiar with the New Testament may make the connection to Jesus praying in the garden of Gethsemane, asking his friends and disciples Peter, James, and John to watch and pray, only to soon find them fast asleep (Mark 14:37-38). Nancy’s loneliness and vulnerability in the film remind Christians not only of Christ’s experiences in the garden, but also our own isolation and weakness without God.

Yet these films and their connections to Christianity are not instances of simple one-to-one correspondence we can easily tie up into neat packages. Like life (and the Christian life) itself, things aren’t so simple.

Larsen’s consideration of David Cronenberg’s 1986 film The Fly (as well as two of Cronenberg’s other films, Videodrome [1983] and Crash [1996]) delves into a complex yet approachable study of creation, original sin, man’s attempt at playing God, death and decay, and more. Although this section covers only a few pages, it provides plenty of food for thought.

Yet many explorations of films cry out for a deeper examination, especially those well-regarded cornerstone films of horror such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). Readers get not only a glimpse of the young people’s isolation, loneliness, and outright fear, but also the isolation, loneliness, and fear that underlie the cannibalistic family itself. Their separation from society may lead Christians to compare this situation to a sinner’s existence apart from the grace and mercy of God, or even from a community of concerned, caring people.

This and other sections of Fear Not! made me wish the book had gone deeper, made more connections, asked more questions. Larsen is clear to point out that “this book is intended as an entry point for thinking theologically about horror films,” and I applaud it for that. Yet I wished the book was about 50 or so pages longer, not in order to include more films, but to provide more space to explore some of the concepts more fully. Yet, as Larsen says, it is a starting point for further discussion, which is what we’re all after. In fact, many of the books in the Reel Spirituality Monograph Series are designed to be introductions to various aspects of the intersection of theology and film.

This short book serves also serves as a potential bridge to several groups: Christians who enjoy horror, Christians who don’t, and both Christian and non-Christian horror fans who feel they are separated by an impenetrable barrier. They’re not. Everyone can engage in the conversation, and this book is a good starting point.

July 15, 2023

Who's Afraid of Ozu?

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote asking you where you are at the halfway point of your movie watching in 2023. In seeking to continue (and hopefully conclude) my journey through Roger Ebert’s Great Movies list in 2023, I decided to watch the earliest unseen film on that list that I could access, which happened to be Floating Weeds (1959), directed by Yasujirō Ozu.

I confess to being an Ozu infant on my cinematic journey, having previously seen just two of his films, The Only Son (1936) and Tokyo Story (1953). I enjoyed the first and consider the second a masterpiece. Ozu is revered by many cinephiles, critics, and writers. Paul Schrader’s seminal book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (1972) is a book that’s been on my “to read” list for so long, I’m embarrassed that I haven’t yet purchased it. To be honest, I’ve seen more films by either Bresson or Dreyer than I have Ozu.

So why am I hesitant to delve into more of Ozu’s work?

I suppose I listen too much to the usual complaints:

"The films are too similar in theme."

"The camera doesn’t move."

"They’re a little slow." (Roger Ebert’s response to such a statement: “Maybe you’re a little slow.”)

Watching Floating Weeds this week, I didn’t believe any of that. I was transfixed.

Here’s a film about an itinerant Japanese theatre troupe (referenced in the film’s title), arriving in a quiet fishing village for a series of performances during an oppressively hot summer. The leader of the troupe, Komajuro (Ganjiro Nakamura) has chosen this particular village because his former wife Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura) lives there with her son. Komajuro’s mistress Sumiko (Machiko Kyo), also part of the troupe, knows this and reluctantly goes along with it. After all, Komajuro’s the boss.

There’s much more to the story, but I will say little more about the film, other than sharing a short quote from Ebert’s entry for the film in his Great Movies list:

This material could be told in many ways. It could be a soap opera, a musical, a tragedy. Ozu tells it in a series of everyday events. He loves his characters too much to crank up the drama into artificial highs and lows… When you see his films, you feel in the arms of a serenely confident and caring master. In his stories about people who live far away, you recognize, in one way or another, everyone you know.

Isn’t this why we watch movies? To feel something? We’re not experiencing a fleeting emotion, but something substantial, something that lingers in your mind and soul. Floating Weeds is not a movie to be consumed then forgotten. It’s a film that speaks to you, regardless of your race, sex, nationality, or anything else. It you’re human, it will speak to you.

Floating Weeds is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel, Kanopy, and Max. Although it is not yet available on a Criterion Blu-ray, the DVD also contains Ozu's original version of the film, A Story of Floating Weeds (1934).