Andy Wolverton's Blog, page 10

July 18, 2022

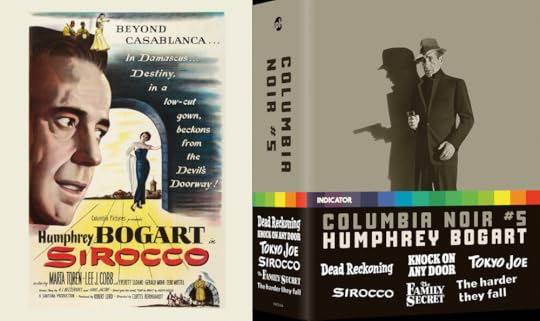

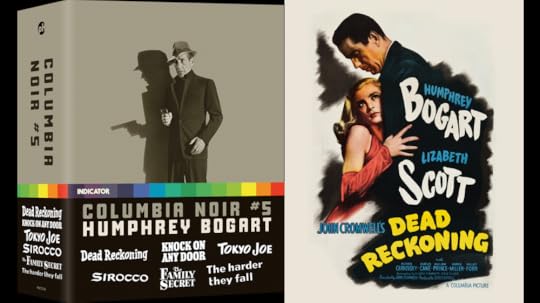

Sirocco (1951) - Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart

Sirocco (1951) directed by Curtis Bernhardt

part of the Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart box set from Indicator

(PLEASE NOTE: This is a REGION B set)

Previously reviewed from this set:

Dead Reckoning (1947)

Knock on Any Door (1949)

Tokyo Joe (1949)

Sirocco is undoubtedly the most unappreciated film in this set and possibly the most reviled. As I describe it, you may understand why, yet when you watch the picture, you might just challenge those majority opinions.

The film begins in 1925 Damascus with a gathering of English and American journalists interviewing Emir Hassan (Onslow Stevens), the Syrian rebel leader seeking to free Syria from French occupation. “You want to know why we Syrians fight the French,” Hassan says. “We fight because they have invaded our country.”

French General LaSalle (Everett Sloane) sees things differently, claiming that the French presence in Syria was mandated by the League of Nations, which settles the matter.

Even if you don’t know much about the history of the Middle East (I certainly don’t, but I can recommend The Arabs: A History by Eugene Rogan as a good starting point), this is an intriguing beginning, and we know we’re likely to see some significant conflict.

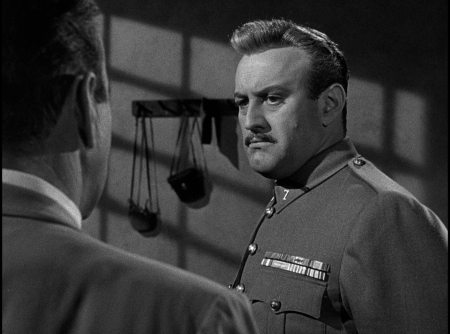

And we do. During an ongoing revolt, we see Syrians hiding and gunning down a French night patrol, the fourth such incident in the past 10 days. Incensed, the general tracks down the rebels and orders their execution. But LaSalle’s Colonel Feroud (Lee J. Cobb) suggests the general wait 48 hours to allow him to discover who is supplying arms to the rebels.

I’m sure no one reading this review will be surprised to discover that the gunrunner is none other than Humphrey Bogart, here as American black marketeer and gambling house operator Harry Smith. We the audience know this, but the French authorities don’t. Yet Smith draws attention to himself when, after Feroud accuses him and four other local food marketers of price gouging, Smith agrees to cooperate while the others balk at the colonel. Smith knows Feroud could simply confiscate the goods, but why shouldn’t Smith play ball and bide his time?

At a local nightclub, Smith eyes a woman named Violetta (Märta Torén), who appears to be attached to Feroud. Smith begins thinking about how he can rectify this situation when something happens that I will not disclose, an event that brings these three characters into each others’ lives creating an interesting triangle.

Smith is resourceful and smart, knowing when he can control a situation and when he can’t. In at attempt to woo Violetta, Smith arranges a harmless (but somewhat costly) ruse that works until it doesn’t. Even so, he has a Plan B and probably a Plan C, D, and E. In another scene, with Feroud taking Violetta to a local restaurant, Violetta notices Smith enjoying a steak at a nearby table. Violetta calls over a waiter and nods toward Smith’s table. “I’ll have what he’s having.” The waiter shakes his head. “Filet mignon. It’s not on the menu. Mr. Smith brings in his own food.”

By this point in the film, most viewers are ready to make the claim that Sirocco is just another rip-off of Casablanca (1942). Both feature Bogart, exotic locales, women who want to escape their current situation, an American with local connections and apparently no loyalties, and protagonists who are forced to make important decisions at the end of their films. While all of those things are present, Sirocco is not, I would argue, an imitator of Casablanca. In the disc’s audio commentary, film historians Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson make this argument far better than I could. Sirocco is a much darker film than Casablanca, with more film noir elements present as well as more cloudy moral dilemmas. It’s too easy and simplistic to claim that Harry Smith is Rick Blaine several years later. (Actually it’s several years earlier, since Sirocco is set in 1925.) Smith is primarily a businessman, and while we may question the true intent of his actions at the end of the film, he’s a far more hardened character than Rick.

Sirocco also arrives on screens several years after WWII, but the French are still a presence in Vietnam in 1951. And let us not forget that HUAC was still a major concern in Hollywood. Screenwriters A.I. Bezzerides and Hans Jacoby clearly had these situations in mind when working on Sirocco. The constant aural presence of gunfire and explosions offscreen remind the viewer that the conflict is constant, with seemingly no end in sight.

Anyone who may view Sirocco and dismiss it would do themselves a disservice by not watching the film again with the audio commentary with Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson, who dismiss many of the Casablanca comparisons and highlight some of the important aspects of the film. More importantly, the two film historians tackle the question of whether Bogart’s career was in a tailspin after 1950’s In a Lonely Place. This period was a complex one for Bogart and frequently misunderstood, yet Heller-Nicholas and Nelson bring some much-needed illumination to the topic.

While Sirocco is not a great film, it is an entertaining, yet dark one that should be enjoyed on its own merits. It is my hope that viewers will discover or rediscover this film.

Although the disc contains only two significant extras, they are both excellent:

Audio commentary with film historians Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson

The South Bank Show: “Bogart: Here’s Looking at You, Kid” (1997, 52. min.)

This very welcome extra is a real treat covering Bogart’s entire life and career featuring Bogart’s son Stephen Bogart, who initially distanced himself from his father’s legacy, then came to embrace it.

Image gallery

Next: The Family Secret (1951)

Most of the images in this post come from ,DVD Beaver. Please consider supporting them.

July 12, 2022

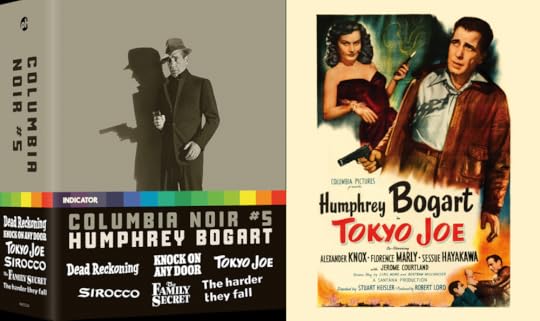

Tokyo Joe (1949) - Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart

Tokyo Joe (1949) directed by Stuart Heisler

part of the Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart box set from Indicator

(PLEASE NOTE: This is a REGION B set)

Previously reviewed from this set:

Dead Reckoning (1947)

Knock on Any Door (1949)

Tokyo Joe, the second Santana Productions film from this set, finds Bogart as ex-Air Force Colonel Joe Barrett, who returns to Japan after the war to see if his bar, Tokyo Joe’s, is still intact. It is, now being run by his friend Ito (Teru Shimada), but Joe discovers that things have changed. A bigger surprise awaits Joe when he finds his wife Trina (Florence Marly), whom he thought died in the war. Joe gets yet another shock when he learns Trina’s divorced him in absentia to marry Mark Landis (Alexander Knox), an American lawyer working in Japan.

Joe understands that his 60-day visitor’s permit and lack of funds won’t give him adequate time to win Trina back, so he’s forced to set up a business that will keep him in Tokyo. An airline freight company would do the trick, but he needs financial backing. Baron Kimura (Sessue Hayakawa), former head of the Japanese police can back Joe financially, but that guarantee comes with a price. To tell you more would ruin the fun.

Tokyo Joe is far from a great film, but it contains several interesting and sometimes compelling elements. Second unit director Art Black and cameramen Joseph Biroc and Emil Oster Jr. were the first crew on an American film allowed to shoot in postwar Japan. The images they capture tell a sobering visual story of the country’s life after defeat as well as its rebuilding. The film also resurrected the career of Sessue Hayakawa with his restrained but menacing role as Baron Kimura. And how often do we see Bogart onscreen holding a conversation with a young child (Trina’s daughter Anya, played by Lora Lee Michel)?

The film also serves as a strange type of “What if?” picture compared with Casablanca (1942). As with Rick Blaine’s isolation in that film, Barrett finds himself in the same type of dilemma in Tokyo Joe: an American who can’t leave without giving up what he really wants, his wife Trina. A song also serves as a reminder of misery of each Bogart character, “As Time Goes By” in Casablanca, and “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)” from Toyko Joe. (In his appreciation on this disc, Bertrand Tavernier makes the case for “These Foolish Things” being the better song.) Yet the more intriguing question remains: What if Rick had changed his mind at the end of Casablanca, come after Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) and stood up to Victor Lazlo (Paul Heinreid)?

On the not-so-great side, Toyko Joe is quite bigoted, portraying most of its Japanese characters as little more than rank stereotypes. Also Bogart was not happy with the casting of Florence Marly as Trina. Marly is visually striking, but lifeless and uninteresting in the role. The sequence of events leading up to the picture’s finale (and the finale itself) go out on a limb that’s nearly completely sawed off.

Despite the film’s problems, I enjoyed it, but the real treasures of the Tokyo Joe disc can be found in its supplements:

Audio commentary with writer and film historian Nora Fiore (aka The Nitrate Diva)

Fiore takes the viewer on a whirlwind tour of the people behind the film, the production history, and much more. This is a tremendous commentary you shouldn’t miss.

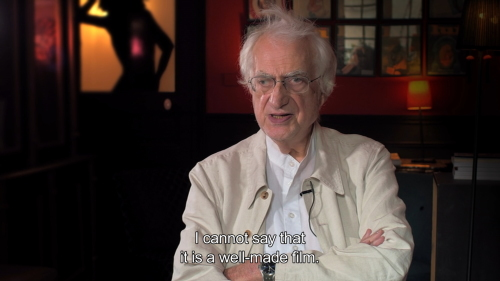

Bertrand Tavernier on Tokyo Joe (2017, 33 min.)

Tavernier, while recognizing the picture's limitations, champions both the film and its director Stuart Heisler, explaining why the director was so misunderstood and hard to pin down stylistically. Tavernier’s knowledge of cinema was vast (which is only one of the reasons he’s missed since his passing last year), and he says a tremendous amount about Tokyo Joe and more in just over half an hour.

A Superstar Returns (2022, 15 min.)

If all you know of Sessue Hayakawa comes from his performance as Colonel Saito in Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), you’re in for a surprise. Hayakawa was a major film star in the silent era, and this tribute by archivist Tom Vincent is a welcome addition to the disc.

Second unit photography (1948, 11 min.)

As mentioned above, a valuable look at postwar Tokyo.

The Negro Soldier (1944, 41 min.)

Jim Pines on The Negro Soldier (2010, 41 min.)

This short, commissioned by the U.S. War Department as a recruiting film for African American enlistees, was directed by Stuart Heisler and stands as a fascinating work that was enormously daring for its time. Heisler actually inherited the project and decided to hold nothing back, not only in directing it, but also in depicting the contribution of African Americans throughout U.S. history. Carlton Moss, who wrote the script, also portrays the preacher in the film. As an added bonus, viewers have the option of a commentary track by author and lecturer Jim Pines, who discusses the history and importance of the film as well as other films featuring African Americans such as Home of the Brave (1949), Buck and the Preacher (1972) and more.

Image Gallery

The selection here is fewer than the previous two films (only 30), but generally of better quality.

Tokyo Joe contains the collection’s best supplementary features thus far. These are all extras worth watching and rewatching.

Next: Sirocco (1951)

Most of the images in this post come from ,DVD Beaver. Please consider supporting them.

July 10, 2022

Collateral Damage Meets Humanity: Dogfight (1991) Nancy Savoca

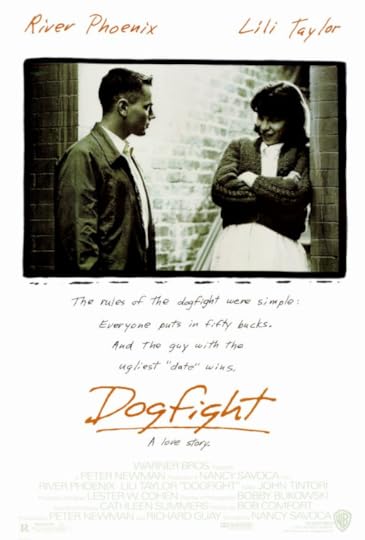

“The rules of the dogfight were simple: Everyone puts in fifty bucks. And the guy with the ugliest ‘date’ wins.”

This text, meant to resemble handwriting, appears on the Dogfight movie poster just below a black-and-white photo of a young couple in the early stages of a relationship. The picture suggests an awkward shyness on the part of the woman and a patient determination from the man. Underneath the title we find a phrase that confirms our suspicions: “A love story.” We think we’ve seen this before and know where it’s going, but don’t be so sure.

Most of Dogfight unfolds in 1963 San Francisco, although the time and place may not be immediately apparent to those unfamiliar with the city or the era. This is a very different San Francisco from the one we would later know: 1967’s Summer of Love, an iconic period marked by hippie culture, Haight-Ashbury, drugs, rock, and “free love.” With the exception of a tiki bar and some neon signs, the colors of this 1963 setting are somewhat reserved, the sights and sounds subdued. Yet San Francisco is a port city, so the potential for excitement is always in the air, especially when a group of young Marines arrives in town looking for a night of fun.

River Phoenix plays Eddie Birdlace, one member of a quartet of Marine buddies on their last night of leave before heading to “a little country called Vietnam,” a place that doesn’t yet mean much to them or most Americans. These guys are prepping for the aforementioned dogfight, as excited as if they were going into battle, and perhaps they are. As was the case for many soldiers in Vietnam, they could be in for some surprises.

Only one of these jokers is going to walk away from the dogfight with significant folding money, and they will all trample some hearts, but the money - to say nothing of the success of their “mission” - is what’s important. When you’re in a battle, you aren’t concerned about collateral damage.

To get out of the rain, Eddie walks into a coffee shop where he hears a woman quietly strumming a guitar, singing softly where most of the customers can’t see or hear her. Moving to the back of the shop, Eddie discovers a waitress on her break and slowly approaches her. The woman’s back is to the camera, and we can sense from her body language that she’s probably shy and awkward.

She turns around, slightly embarrassed, but Eddie seems delighted: This woman named Rose (Lili Taylor) is shy and awkward, her hair a mess, her waitress uniform ill-fitting. Perfect for the dogfight.

After hearing just a snippet of her song, Eddie tells an unconvincing lie about his knowledge of folk music. Rose knows he’s lying, but he’s a good-looking guy, and he’s talking to her. The shot captures the reflection of cascading rain on the wall behind Rose, but when the camera moves to Eddie, he’s standing in front of a wall that looks vibrant, as if it were painted just moments ago. The positioning of these two characters this early in the film is significant, because in a later scene the situation will be very different.

As Eddie works his charm, Rose busies herself, filling a sugar container that’s already full, not trusting herself to make eye contact, but rather looking around to confirm that she’s not dreaming. During their introductions, Eddie proves he is who he says he is, showing Rose his military issue ID. Rose examines his picture and says, “Gosh, you look so angry.” Eddie’s response? “I’m not angry. I’m just ready.”

Both of his statements are lies, which Rose discovers as the “dogfight” (of which initially she is painfully unaware) unfolds. Eddie’s friends are jerks, caring only for themselves and their own pleasures, unconcerned with whom they may hurt. Women exist only for men’s pleasure, so there’s no harm done, right? These are the rules of the game, and it’s a game much larger than this dogfight.

I will not reveal what happens next, but you know that Rose is eventually going to get wise to what’s going on. I won’t tell you how that plays out, but I will visit another scene that provides a fascinating contrast with the coffee shop meeting.

Eddie and Rose find themselves in a club that’s closing down for the night. With no one else around, Eddie asks Rose to step up onstage and sing something for him. Tentatively Rose seats herself at the piano, touches the keys a bit, and demurs, yet Eddie encourages her to continue. Softly, but with more confidence than she displayed in the coffee shop, Rose begins to sing the Malvina Reynolds song “What Have They Done to the Rain”:

Just a little rain falling all around,

The grass lifts its head to the heavenly sound,

Just a little rain, just a little rain,

What have they done to the rain?

Just a little boy standing in the rain,

The gentle rain that falls for years.

And the grass is gone,

The boy disappears,

And rain keeps falling like helpless tears,

And what have they done to the rain?

Just a little breeze out of the sky,

The leaves pat their hands as the breeze blows by,

Just a little breeze with some smoke in its eye,

What have they done to the rain?

Just a little boy standing in the rain,

The gentle rain that falls for years.

And the grass is gone,

The boy disappears,

And rain keeps falling like helpless tears,

And what have they done to the rain?

The director and producers could have chosen many songs from this era, but “What Have They Done to the Rain” is the perfect choice. The lyrics not only capture the joy and celebration of what Rose hopes will turn into a flourishing and lasting relationship, but also becomes a harbinger of corruption, a once good and natural occurrence that has turned poisonous, deadly, and devastating. It brings to mind ruined innocence, misplaced trust, and broken promises without a hint of remorse.

This alone would be a potent moment in an already engaging film, but director Nancy Savoca makes a couple of brilliant choices. The camera begins with a tight shot of Rose at the piano, a very personal, very vulnerable shot. She fills the screen even if her voice doesn’t. Yet slowly, as with the song’s lyrics, the camera pulls back to reveal the bigger picture of Rose as a complete person and not just a face.

Both the lyrics and Rose’s delivery of the song work on Eddie as we see him seated at a table in a medium-long shot. There’s a chess board within reach, indicating the game he and his buddies have been playing, and he’s smoking a cigarette in a carefree manner. As the camera slowly moves toward him, we see that just maybe he’s understanding the song’s words, but more importantly he’s seeing Rose for the first time, realizing how she is changing him for the better, making him more human, more caring. River Phoenix was such a gifted actor that he can portray this revelation not only with a look, but also in his body language, the way he pulls the cigarette away and stares at this woman with a staggering sense of wonder.

Eddie looks at everything differently now, although something happens near the end of the film - and the Marines’ night out - that makes us wonder if the lesson stuck. Dogfight also shows us that we as a nation began to look at everything differently after Vietnam. We haven’t learned all the lessons we need to learn, but - like Eddie - maybe we’re just beginning to understand that people matter. Everyone should be treated with dignity. Savoca pulls this off in a subtle way, refusing to hit us over the head with it, and Dogfight is more powerful because of it.

Sometimes it takes a Rose (and a tremendous performance from an actor like Lili Taylor) to help us realize that there are people in our lives that the world doesn’t deserve. Rose is a heartbreaking character because she exists in the midst of a multitude who see in her nothing more than someone to laugh at or tease. Yet if we listen to her, she works on us, not in the way combatants assault one another, but with pure humanity. Rose’s humanity devastates us, because it reminds far too many of us that we lack it. She is a treasure. So is this film.

Dogfight is available on DVD from Warner Archive. Let’s hope they upgrade this to Blu-ray status soon.

July 7, 2022

Watching Movies Together: It's Not Just Fun, It's Essential

Tonight we're showing Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) at the Severna Park Library where I work. A movie at the library... No big deal, right?

Wrong.

This isn't just a fun time watching an '80s classic at the library. It's building community. Tonight we're going to laugh, be thrilled, and filled with wonder at an amazing film that was created without CGI technology. It's a movie that adults and kids can enjoy on different levels. But the important thing about this event isn't the movie itself. It's the discussion afterward. As Roger Ebert called his Ebert Interruptus events, it's democracy in the dark.

People will be able to share their opinions on the movie, and every voice is welcome. It gives the audience the opportunity to hear others' opinions as well, to perhaps think about something they hadn't considered before. There's always plenty to talk about at these events, and the movies don't have to be high-brow or art house, but it's fine if they are.

We are all still trying to navigate our way back to pre-Covid experiences. We've been isolated for too long, and many have forgotten how to connect and interact with others. Events like this bring people together. It's really more about building community than it is about watching a movie (although that's lots of fun!). I talk about this in my book Men Don't Read, but it applies to many types of library programs. If your library isn't having movie events, I urge you to consider starting some. You don't have to be a movie expert. Just show a movie (Check your licensing requirements first!), let the audience discuss it afterward, and you'll begin to see magic happen.

Thanks for reading.

July 5, 2022

Knock on Any Door (1949) - Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart

Knock on Any Door (1949) directed by Nicholas Ray

part of the Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart box set from Indicator

(PLEASE NOTE: This is a REGION B set)

Previously reviewed from this set: Dead Reckoning (1947)

Knock on Any Door, the first film produced by Humphrey Bogart’s independent company Santana Productions, knocks on several doors, which becomes both the picture’s strength and its weakness.

Like Dead Reckoning, the first title in the Columbia Noir #5 box set, Knock on Any Door drops us into a city street at night. We witness a shootout in an alley where a cop is shot and killed. A young criminal named Nick “Pretty Boy” Romano (John Derek, in his film debut, unless you count a very small role in 1947’s A Double Life) gets tagged for the crime and thrown in the slammer, awaiting legal representation. We’ve seen all this before, even in 1949.

Cut to attorney Andrew Morton (Bogart) at home on the phone, turning down a potential client. Finishing his conversation, Morton sits down to resume a game of chess with his wife Adele (Candy Toxton, credited as Susan Perry). As the game continues, Morton tries to convince himself that turning down the case is the right thing to do. Although she never says a word, Adele apparently has the ability to change her husband’s mind simply by her presence. (We sense this isn’t the first time she’s done this. Or perhaps she knows he has to argue with himself before making final decisions.) Morton takes the client, which is, of course, Nick Romano.

Cue Flashback Central: We learn that Nick wasn’t really a bad kid, he just got in with the wrong crowd. Living in poverty and in a single-parent family can contribute to that. As Nick is drawn into a life of crime he justifies his behavior with what has become the film’s most famous line: “Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.”

When Nick finds a nice girl named Emma (Allene Roberts) he tries the straight-and-narrow for a while. We’ve seen all this before as well.

Earlier in the decade Bogart might have played the Nick Romano character. In the 1930s, he would’ve portrayed one of the young hoods hanging out with Nick. Here he plays the lawyer who grew up in the same environment as Nick, which provides one of those strength/weakness contrasts I mentioned earlier. Years earlier Morton was responsible for putting Nick’s dad in prison where he died, so the lawyer is clearly seeking to make things right this time around. Now we understand why he didn’t want the case.

Much of this is familiar, and large parts of the film would be routine if not for Bogart’s performance. John Derek (regardless of what we think of his later career and behavior) gets the job done, which is about the best you can hope for when you’re standing toe to toe with Bogart. Nick’s character is mostly unlikable, becoming a symbol (a major weakness) rather than a character as the film draws to its conclusion.

Casting Barry Kelley as a judge is something of a head-scratcher, but George Macready as District Attorney Kerman is a perfect choice, although the character is written primarily as a one-dimensional foil for Morton. Yet the courtroom scenes are the best parts of the film, including a nice interior voiceover as Morton examines the jury members, scenes with witnesses that are both comedic and intense, and a wonderful moment in which Kerman taunts Nick on the stand, calling him “Pretty Boy” while the DA fingers his own (real) facial scar.

It’s unfair to judge a film for what it should have been rather than what it is, but had Knock on Any Door focused on Morton’s guilt and fears that he might let down the Romano family again, we might have had a better picture. The film is also extremely didactic in its last reel. Morton’s closing argument is certainly passionate, but soon grows preachy.

One of the film’s strengths is Ray’s insistence on detail, which includes the sweat on the faces of people in the courtroom, tight shots of Nick in confined spaces implying capture, and scenes on or near staircases conveying instability. Yet details should refine something that’s already well-established.

The real weakness of the film is in making Nick a symbol, a victim of his environment. Yes, he is an outsider, unable to fit into normal society. While impressively shot, the final moments of the film make sure we understand who’s really at fault here, reducing the characters to metaphors. It’s the old nature vs. nurture argument, which is endless, yet this is some of the same territory Nicholas Ray explored in his first film They Live by Night (1948). Throughout his career, Ray was fascinated by and sympathetic toward the outcast, which we would see several years later in his most famous film Rebel without a Cause (1955). Knock on Any Door is something of a dress rehearsal for that film, and while it contains many good moments, watching it can be a frustrating experience.

EXTRAS

Audio commentary with writer and film historian Pamela Hutchinson

Nobody Knows How Anybody Feels (2022, 20 min.) appreciation by critic and film programmer Geoff Andrew

Andrew does a fine job exploring several aspects of the film’s production, creators, themes, and more. I like this a bit more than the Tony Rayns featurette on Dead Reckoning (which is still good) and hope the rest of the subsequent appreciations are up to the level Andrew establishes here.

Tuesday in November (1945, 17 min.)

Produced by the Office of War for the series The American Scene, this short (with Ray serving as assistant director) describing the democratic process of the American government was originally meant for overseas distribution, but was probably shown to American children well into the 1950s.

Theatrical trailer

Image gallery

61 images, again, of varying quality

Next: Tokyo Joe (1949)

Most of the images in this post come from DVD Beaver. Please consider supporting them.

July 1, 2022

Dead Reckoning (1947) - Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart

Dead Reckoning (1947) directed by John Cromwell

part of the Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart box set from Indicator

(PLEASE NOTE: This is a REGION B set)

It’s an early Sunday morning in Gulf City, still too early for the sun to come up and nighttime activities to cease. A brightly lit sign boasts “Tropical Paradise of the South.” Few film noir locales can be called tropical, yet some of them seem to guarantee paradise. Gulf City, at least based on our introduction to it, fails to deliver on either promise. Rip Murdock (Humphrey Bogart) would no doubt confirm this failure of the city as he attempts to slip and slide through its rain-soaked city streets, avoiding contact with people, or perhaps trying to distance himself from the police.

Rip stumbles around the city, looking disheveled as if he’s just barely escaped a beating. He dashes into a church, eyes a priest, and corners him. Father Logan (James Bell) turns out to be a man in uniform, a paratrooper just like Rip. Maybe he’ll understand. The words spill out of Rip like a flood: “I’ve gotta tell somebody about this thing before something happens to me.”

Rip takes the priest (and the audience) for a ride on The Flashback Express which transports Rip and his paratrooper buddy Johnny Drake (William Prince) from a Paris hospital to a train headed to Washington, D.C. where they are scheduled to receive a hero’s welcome and medals for their bravery during the war. Rip is excited mostly for Johnny, whom Rip believes is more deserving of all the attention. Johnny, however, is nervous, and not because he’s camera-shy. When the train stops and the press want to photograph and interview the duo, Johnny runs away and hops another train headed in the opposite direction, leaving Rip alone and confused.

In a couple of days Rip learns that Johnny was killed in an auto accident in Johnny’s hometown of Gulf City. Suspecting that something’s fishy, Rip travels to Gulf City to discover the truth.

While in the “Tropical Paradise of the South,” Rip discovers that Johnny wasn’t completely honest about his past. I won’t go into the particulars, but it appears Johnny was involved in some shenanigans with a married nightclub singer named Coral Chandler (Lizabeth Scott). That involvement led to murder, which could explain why Rip is having so much trouble getting straight answers from anyone. Can Rip trust Coral, the local cops, or anyone in Gulf City?

This early in the game (about 15 or so minutes) we recognize that Dead Reckoning contains several of the necessary elements to constitute a good or maybe even a top-notch film noir. We’ve got Bogart, Scott, scriptwriter Steve Fisher, a mysterious past, a supporting cast of characters we’re pretty sure we can’t trust, hardboiled banter, and more. Dead Reckoning is good, but not great, and here’s why:

Rip makes a transition in character that isn’t totally believable. We buy it because it’s Bogart, and we’re used to seeing Bogart perform in a certain way: confident, savvy, independent, a man with smarts and tough talk, knowing how to handle the ladies, calling all the shots. But we see little of this at the beginning of the film. Rip is just a typical soldier, maybe a bit atypical because he and Johnny are about to be decorated, but it’s clear that Johnny is the one who’s more worthy of being honored. Rip seems like a regular G.I. who’s used to following orders and was just doing his duty. But once he hits Gulf City, Rip becomes Sam Spade, complete with hardboiled banter and mannerisms that seem as if he borrowed them from The Maltese Falcon clearinghouse. When Rip discovers a dead body in his room, he’s got the smarts and resourcefulness of a Sam Spade, knowing exactly what to do without a second thought.

Speaking of The Maltese Falcon (made just just six years before Dead Reckoning), the script contains too many allusions to the John Huston classic. Not only do we get lines that are so similar to The Maltese Falcon (“You know, you do awful good,” and “When a guy’s pal is killed, he ought to do something about it”), we also get a sadistic henchman (Marvin Miller) who dreams of kicking Rip in the head whenever possible, and Rip on the wrong end of a Mickey delivered by a club owner named Martinelli (Morris Carnovsky). It’s fine to pay homage to a classic, but Dead Reckoning relies too much on devices from a better, more memorable film.

Although she’s not great, Lizabeth Scott gets the job done. Let’s not forget that in this picture Scott is something of a Lauren Bacall substitute, or more correctly, a Rita Hayworth substitute, as Hayworth was originally chosen for the role. This was also only Scott’s third film, and here she often seems bland and unexpressive. Yet to her credit, perhaps Scott is exactly right for the part, especially when we consider her performance in light of the character of Coral as it develops throughout the film.

The film generally looks good, but you’ll see at least a couple of instances of awkward editing and clunky cinematography, particularly cuts between points-of-view in which the lighting doesn’t match either in backgrounds or on actors’ faces.

Yet there’s plenty of good stuff here as well. When speaking to the priest, Rip’s face is often in the shadows, portraying either that his lack of knowledge has him “in the dark,” or perhaps showing us that the city’s darkness has swallowed his soul. There’s also a wonderful scene where Rip lures Coral to the dance floor in order to administer his own clever lie detector test.

It’s subtle and probably not accidental, but there’s the friendship angle that is briefly explored in a way that doesn’t necessarily try to steal from The Maltese Falcon. Early in the film, Rip trusts Father Logan because they are part of a brotherhood of paratroopers. Rip believes in Johnny because of what they’ve been through during the war. He trusts Johnny, so the priest must be worthy of trust as well. Rip cares enough about his friend to take a chance on a priest who probably understands him in a way that no one else can.

Overall Dead Reckoning is a good, but not great noir I will enjoy revisiting.

EXTRAS

Audio commentary with film scholar, preservationist, and historian Alan K. Rode

Although I have not yet listened to all of this commentary, Rode is knowledge and his presentations are always first-rate. I look forward to listening to this track in its entirety.

A Pretty Good Shot (2022, 17 min.) appreciation by writer and film programmer Tony Rayns

Rayns offers an excellent overview of the casting decisions in the film, how Bogart was brought over from Warner Bros. and Lizabeth Scott from Paramount, director John Cromwell’s career, and more. Rayns also explores some of the film’s themes such as servicemen returning to a chaotic and unfamiliar America. Although he spends a little too much time summarizing the film’s plot, Rayns brings a knowledgable eye to the picture’s background and development. Well worth your time.

Watchtower Over Tomorrow (1945, 16 min.)

Indicator continues the addition of these short films that people have either forgotten about or weren’t aware of in the first place. These are typically featurettes that share a theme, director, producer, or star from the main film on the disc. Watchtower Over Tomorrow, directed by John Cromwell, is essentially a public service propaganda film from the War Activities Committee giving us a tour of how the United Nations was formed after WWII. I’m glad these films exist, they are interesting archival works, but you’ll probably only watch it once. At least we get to see Lionel Stander.

Image Gallery

80 stills of varying quality

Next: Knock On Any Door (1949)

Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart - Dead Reckoning (1947)

Dead Reckoning (1947) directed by John Cromwell

part of the Columbia Noir #5: Humphrey Bogart box set from Indicator

It’s an early Sunday morning in Gulf City, still too early for the sun to come up and nighttime activities to cease. A brightly lit sign boasts “Tropical Paradise of the South.” Few film noir locales can be called tropical, yet some of them seem to guarantee paradise. Gulf City, at least based on our introduction to it, fails to deliver on either promise. Rip Murdock (Humphrey Bogart) would no doubt confirm this failure of the city as he attempts to slip and slide through its rain-soaked city streets, avoiding contact with people, or perhaps trying to distance himself from the police.

Rip stumbles around the city, looking disheveled as if he’s just barely escaped a beating. He dashes into a church, eyes a priest, and corners him. Father Logan (James Bell) turns out to be a man in uniform, a paratrooper just like Rip. Maybe he’ll understand. The words spill out of Rip like a flood: “I’ve gotta tell somebody about this thing before something happens to me.”

Rip takes the priest (and the audience) for a ride on The Flashback Express which transports Rip and his paratrooper buddy Johnny Drake (William Prince) from a Paris hospital to a train headed to Washington, D.C. where they are scheduled to receive a hero’s welcome and medals for their bravery during the war. Rip is excited mostly for Johnny, whom Rip believes is more deserving of all the attention. Johnny, however, is nervous, and not because he’s camera-shy. When the train stops and the press want to photograph and interview the duo, Johnny runs away and hops another train headed in the opposite direction, leaving Rip alone and confused.

In a couple of days Rip learns that Johnny was killed in an auto accident in Johnny’s hometown of Gulf City. Suspecting that something’s fishy, Rip travels to Gulf City to discover the truth.

While in the “Tropical Paradise of the South,” Rip discovers that Johnny wasn’t completely honest about his past. I won’t go into the particulars, but it appears Johnny was involved in some shenanigans with a married nightclub singer named Coral Chandler (Lizabeth Scott). That involvement led to murder, which could explain why Rip is having so much trouble getting straight answers from anyone. Can Rip trust Coral, the local cops, or anyone in Gulf City?

This early in the game (about 15 or so minutes) we recognize that Dead Reckoning contains several of the necessary elements to constitute a good or maybe even a top-notch film noir. We’ve got Bogart, Scott, scriptwriter Steve Fisher, a mysterious past, a supporting cast of characters we’re pretty sure we can’t trust, hardboiled banter, and more. Dead Reckoning is good, but not great, and here’s why:

Rip makes a transition in character that isn’t totally believable. We buy it because it’s Bogart, and we’re used to seeing Bogart perform in a certain way: confident, savvy, independent, a man with smarts and tough talk, knowing how to handle the ladies, calling all the shots. But we see little of this at the beginning of the film. Rip is just a typical soldier, maybe a bit atypical because he and Johnny are about to be decorated, but it’s clear that Johnny is the one who’s more worthy of being honored. Rip seems like a regular G.I. who’s used to following orders and was just doing his duty. But once he hits Gulf City, Rip becomes Sam Spade, complete with hardboiled banter and mannerisms that seem as if he borrowed them from The Maltese Falcon clearinghouse. When Rip discovers a dead body in his room, he’s got the smarts and resourcefulness of a Sam Spade, knowing exactly what to do without a second thought.

Speaking of The Maltese Falcon (made just just six years before Dead Reckoning), the script contains too many allusions to the John Huston classic. Not only do we get lines that are so similar to The Maltese Falcon (“You know, you do awful good,” and “When a guy’s pal is killed, he ought to do something about it”), we also get a sadistic henchman (Marvin Miller) who dreams of kicking Rip in the head whenever possible, and Rip on the wrong end of a Mickey delivered by a club owner named Martinelli (Morris Carnovsky). It’s fine to pay homage to a classic, but Dead Reckoning relies too much on devices from a better, more memorable film.

Although she’s not great, Lizabeth Scott gets the job done. Let’s not forget that in this picture Scott is something of a Lauren Bacall substitute, or more correctly, a Rita Hayworth substitute, as Hayworth was originally chosen for the role. This was also only Scott’s third film, and here she often seems bland and unexpressive. Yet to her credit, perhaps Scott is exactly right for the part, especially when we consider her performance in light of the character of Coral as it develops throughout the film.

The film generally looks good, but you’ll see at least a couple of instances of awkward editing and clunky cinematography, particularly cuts between points-of-view in which the lighting doesn’t match either in backgrounds or on actors’ faces.

Yet there’s plenty of good stuff here as well. When speaking to the priest, Rip’s face is often in the shadows, portraying either that his lack of knowledge has him “in the dark,” or perhaps showing us that the city’s darkness has swallowed his soul. There’s also a wonderful scene where Rip lures Coral to the dance floor in order to administer his own clever lie detector test.

It’s subtle and probably not accidental, but there’s the friendship angle that is briefly explored in a way that doesn’t necessarily try to steal from The Maltese Falcon. Early in the film, Rip trusts Father Logan because they are part of a brotherhood of paratroopers. Rip believes in Johnny because of what they’ve been through during the war. He trusts Johnny, so the priest must be worthy of trust as well. Rip cares enough about his friend to take a chance on a priest who probably understands him in a way that no one else can.

Overall Dead Reckoning is a good, but not great noir I will enjoy revisiting.

EXTRAS

Audio commentary with film scholar, preservationist, and historian Alan K. Rode

Although I have not yet listened to all of this commentary, Rode is knowledge and his presentations are always first-rate. I look forward to listening to this track in its entirety.

A Pretty Good Shot (2022, 17 min.) appreciation by writer and film programmer Tony Rayns

Rayns offers an excellent overview of the casting decisions in the film, how Bogart was brought over from Warner Bros. and Lizabeth Scott from Paramount, director John Cromwell’s career, and more. Rayns also explores some of the film’s themes such as servicemen returning to a chaotic and unfamiliar America. Although he spends a little too much time summarizing the film’s plot, Rayns brings a knowledgable eye to the picture’s background and development. Well worth your time.

Watchtower Over Tomorrow (1945, 16 min.)

Indicator continues the addition of these short films that people have either forgotten about or weren’t aware of in the first place. These are typically featurettes that share a theme, director, producer, or star from the main film on the disc. Watchtower Over Tomorrow, directed by John Cromwell, is essentially a public service propaganda film from the War Activities Committee giving us a tour of how the United Nations was formed after WWII. I’m glad these films exist, they are interesting archival works, but you’ll probably only watch it once. At least we get to see Lionel Stander.

Image Gallery

80 stills of varying quality

Next: Knock On Any Door (1949)

June 25, 2022

Need Some Film Noir Suggestions?

Kino Lorber is having a great Spring Into Summer sale which includes a ton of film noir titles on the cheap. I've got some single-disc suggestions for you in this video:

https://youtu.be/YYkERY8wW-UMay 29, 2022

Film Noir New Releases for June 2022

Right now I'm only posting the video version of my report on new releases in film noir and neo-noir. Thanks for watching!

May 25, 2022

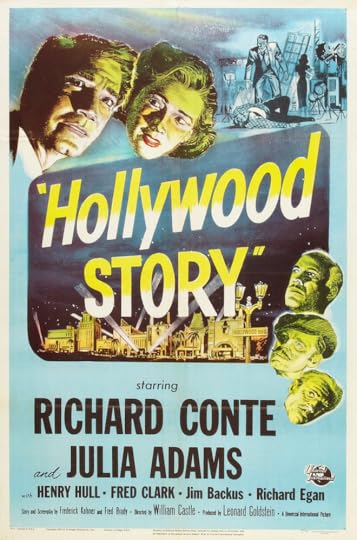

Hollywood Story (1951), or "Richard Conte Lite"

Hollywood Story (1951) William Castle

Before he became the gimmick master of thrillers and horror movies in the late ‘50s, William Castle made several crime pictures including Hollywood Story (1951) for Universal International.

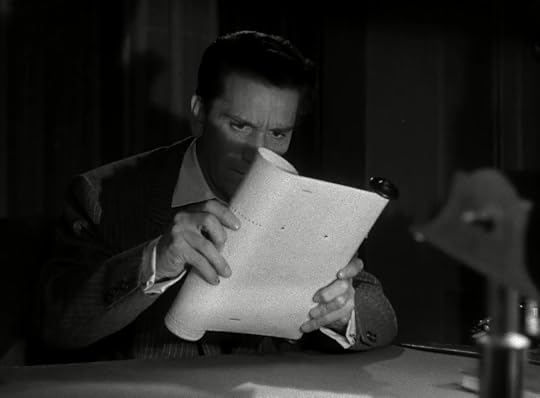

Richard Conte (center) plays Larry O’Brien, a New York producer who wants to transition to making movies in Hollywood. Thanks to his friend and publicist Mitch Davis (Jim Backus, right), O’Brien purchases an old studio that’s been vacant since the silent era. Once Davis leads O’Brien into the bungalow where the famous silent film director Franklin Ferrara was mysteriously murdered 20 years earlier, O’Brien knows he’s got his first picture idea: a documentary on Ferrara.

Davis tells his friend that neither he nor anyone else knows who killed Ferrara. “Someone knows,” O’Brien counters. “The person who killed him.”

O’Brien’s obsession with Ferrara leads to encounters with various people, all of whom become sources of information and potential suspects, including O’Brien’s business partner Sam Collyer (Fred Clark), who thinks the film project is a bad idea.

But there’s also Sally Rousseau (Julie Adams), a woman who knows the case and clearly has secrets of her own. And what about police Lieutenant Bud Lennox (Richard Egan, below), who appears to be sometimes assisting, sometimes hindering O’Brien’s investigation. But when a gunman’s bullet narrowly misses O’Brien, the filmmaker begins to think that digging into the case might be bad for his health.

Two things are clear: Hollywood Story is loosely based on the famous unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor in 1922, and the picture is meant to capitalize on the then recent film Sunset Boulevard. When you understand that Hollywood Story was never meant to blow the lid off the William Desmond Taylor case, it becomes a fairly interesting venture, more mystery than noir.

Yet watching the film requires the viewer to ignore several questions in believability that could’ve brought the storyline to a complete halt, including plot holes (no, let’s call them craters), the idea that this bungalow has been sitting around untouched for over 20 years (combined with a security guard who’ll seemingly let anyone inside), and an extremely unlikely ending featuring some awful gunplay. As long as you go with the flow (or torrential flood), you’ve got a reasonably good shot at enjoying the picture.

My biggest problem with the film is that Richard Conte isn’t a tough guy here, although much of the problem comes from the way the part is written. Even when he knows he’s being lied to by multiple characters, O’Brien exactly doesn’t put on the heat. (It’s more like an old hand warmer.) Any halfway successful New York producer should have more bite than this guy. And of course an outsider with no previous knowledge of the case is going to be able to solve it in 77 minutes. Sure, no problem. Conte has often played smart characters with plenty of sense, but too many things come far too easy for O’Brien.

This is indeed a low-budget affair, but it features some good supporting players, including Fred Clark, Julie Adams, and Henry Hull. Plus you’ll see cameos from several actors from the silent era including Francis X. Bushman, William Farnum, Betty Blythe, Helen Gibson, and Joel McCrea, who appeared uncredited (as he does here) in several silent films before he became a major star.

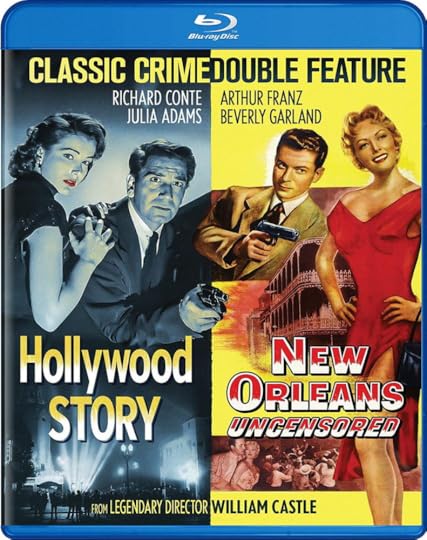

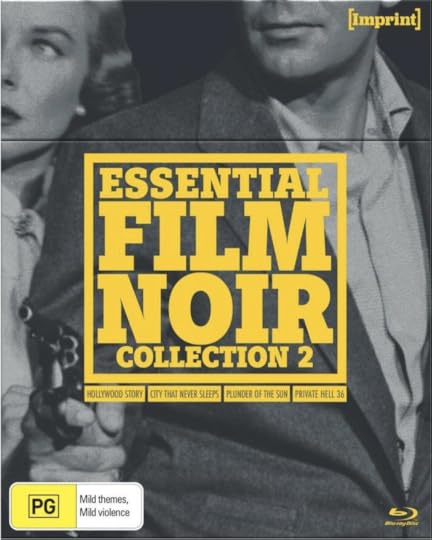

You can find Hollywood Story on a 2-disc double feature (with another Castle film, New Orleans Uncensored) Blu-ray from Mill Creek as well as Essential Film Noir - Collection 2 from the Australian company Import, which also includes City That Never Sleeps (1953), Plunder of the Sun (1953), and Private Hell 36 (1954).

Photos from DVD Beaver and IMDb.