Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 155

July 17, 2021

An artist in Germany, Norway, Scotland, Isle of Man, then Somerset

AN UNUSUAL CRUCIFIX hands within the church of St Mary in Bruton, Somerset. It is a sculpture typical of early 20th century German Expressionism, yet it was created in 1969, long after the heyday of this artistic trend. The creator of this religious sculpture was Ernst Blensdorf (1896-1976). He was born Ernst Müller in North Germany, but after his marriage to his first wife, Ilse Blensdorf, in 1923, he changed his surname to ‘Müller-Blensdorf’, then later to ‘Blensdorf’.

At first, Blensdorf became a seaman. After having been interned as an enemy alien by the British during WW1, Ernst travelled to Johannesburg in South Africa with a fellow internee. It was here that he made a table-top wood carving of an African village. On his return to Germany, this fine carving persuaded Ernst’s father that his son had a future as an artist and was willing to support him towards this aim. While in Africa, Ernst had seen African art first-hand and exposure to this certainly helped influenced his future creations.

After a brief spell at an art school in Barmen, he left to become apprenticed to a master joiner. By 1922, he had become a journeyman for a furniture company, which specialised in manufacturing luxury items. During this period, he was influenced by the Bauhaus artist Paul Klee and the sculptor Alexander Archipenko. The skill that Ernest acquired and developed whilst manufacturing wooden objects for the furniture company became useful as he moved from applied craftsmanship to artistic endeavours. In addition to other activities, he taught at the art school in Barmen during the 1920s. By the 1930s, he had become an established sculptor and had exhibited his works at various exhibitions in Germany, where he received both private and public commissions.

When the Nazis took power in Germany, Blensdorf became one of the first artists whose works were categorised as ‘degenerate’ by Hitler and his regime. This led to him losing his teaching post at Barmen and his studio being wrecked by the Nazi’s loutish followers. Ernst, his wife, and children, moved to Norway, where he was planning a giant peace monument to honour the Norwegian statesman and Nobel Peace prize winner Fridjtof Nansen. In Norway, he worked on this project and made a living creating and selling artistic ceramic works, alongside the Norwegian ceramicist Eilif Whist.

When the Germans invaded Norway in spring 1940, Blensdorf and his children fled to Scotland. His wife, Ilse, remained behind, saying that she was a follower of Adolf Hitler. Following his arrival in the UK, Blensdorf was once again interned as an ‘enemy alien’. Along with many others, including a good number of men with artistic talent and German nationality, he was interned on the Isle of Man (from 1940 to 1941). His children were placed in a couple of orphanages. While interned, he, along with fellow artists, were allowed to satisfy their creative urges and even to sell their creations. Using whatever materials he could find during this period of scarcity, Blensdorf’s creative output was impressively large. For the first time in his life, he had plenty of time to undertake artistic work in the absence of anxieties such as he had experienced before arriving on the Isle of Man.

Blensdorf was released from internment in 1941. He went to live with an Austrian couple, the Schreiners, whom he had met in the internment camp. They lived in Charlton Musgrove in Somerset. With him, the Schreiners planned to set up an art school, but this failed for financial reasons. Ernst remained in Somerset. His first job was teaching pottery at a school in Bratton Seymour. It was here that he met his second wife, Jane Lawson. They married in 1942 and moved into a house near Wincanton, where they were joined by his children. Blensdorf taught in various schools in Somerset including the King’s School in Bruton.

In 1943, Blensdorf and his family bought a run-down 17th century house close to Bruton. Gradually, the house was restored and improved. It remained his home for the rest of his life. Although he exhibited often and in prestigious venues, Blensdorf never realised the great reputations that other artists, such as Henry Moore, Elizabeth Frink, Anthony Caro, and Barbara Hepworth, gained in the UK and beyond. For this reason, seeing his work for the first time during my first visit to the lovely Bruton Museum in July 2021, was a wonderful surprise and an exciting eye-opener. In one corner of this small museum, there is a large glass cabinet that contains examples of Blensdorf’s sketches, ceramics, and sculptures. When I told the lady, who was looking after the museum, how much I liked what I had seen of his works, she told me about the crucifix in the local church, which fortunately I was able to see. She also sold me a copy of a well-illustrated catalogue of an exhibition of his works that was held some time ago in the Bruton Museum. It is from this publication that I have extracted much of the information above. Bruton is a gem of a town. Visiting its museum is a ‘must’ because not only does it allow you to ‘discover’ the works of Blensdorf but also to see a display of artefacts relating to the author John Steinbeck, who lived close to Bruton between March and September 1959 … but that is another story.

July 16, 2021

Born in Portugal, hanging in the Tate

THE TATE BRITAIN is currently hosting a wonderful exhibition of the works of Paula Rego, born 1935 in Lisbon, Portugal during the fascist dictatorship of Antonio Salazar (1889-1970), who was in office from 1932 to 1968. Her father was anti-fascist and anglophile. He sent Paula to a finishing school in Kent (UK) when she was 16. Later, she enrolled to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art, part of London’s University College. While she was studying there (from 1952 until 1956), she met her future husband, the painter Victor Willing (1928-1988). They married in 1959, following Victor’s divorce from his first wife. Paula and Victor lived between Portugal and the UK, finally settling in the latter in 1972.

Distributed within eleven rooms of the Tate Britain, Rego’s works are well displayed, some of them with informative panels placed beside them. Her paintings express her political (anti-fascist) and social consciousness, some of which is concerned with the ill-treatment of, and the indignities inflicted on, women, especially in the country where she was born.

Rego’s paintings are dramatic, colourful, powerful, and not lacking in a sense of humour. They are sometimes almost abstract, but the element of figurativeness is never completely absent. Her paintings often lean towards surrealism. Whether they are expressing subversion, or love, or depression, or pure fantasy, they are visually intriguing and cannot fail to engage the viewer. Throughout her works, which span several decades, the influence of her native land can be discerned, sometimes without difficulty, other times with the assistance of the informative labels by their side.

The exhibition, which opened on the 7th of July 2021, will continue until the 24th of October 2021. So, there is plenty of time for you to enjoy this superb exhibition of the fabulous works of this fascinating artist. It is an exhibition that once again demonstrates that great art is often created as a reaction to an oppressive regime.

July 15, 2021

Shifted to Somerset from London

EVERY YEAR SINCE 2000, excepting 2020, The Serpentine Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens has erected a temporary summer pavilion. Each pavilion is designed by a different architect or group of architects. What they have in common is that their pavilion is the first of their designs to be constructed in London, or maybe the UK. They stand in front of the Serpentine Gallery during the summer months and into early autumn. They are always fascinating visually and always contain a café with seating. Over the years some of them have been used as event spaces.

At the end of the season, the pavilions are dismantled and are never seen again in Kensington Gardens. Some of them might be sold and others re-erected elsewhere, but until recently I have never seen one again.

A few years ago, a contemporary art gallery, Hauser and Wirth, which has a branch in London’s West End, bought a farm on the edge of Bruton in Somerset. They have used some of the farm buildings and constructed some new ones to accommodate another branch of their gallery. In addition to the exhibition spaces, there is a superb restaurant, an up-market farm shop, and a wonderful garden created by the Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf (born 1944).

The garden slopes upwards from the gallery. At the top of the slope, there is something that at first sight looks like a giant hamburger patty or the profile of an oversized bagel. I recognised it immediately as being one of the former summer pavilions that once stood next to The Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens. It is the 2014 Serpentine pavilion designed by Smiljan Radic (born 1965 in Santiago, Chile).

When I saw it in London in 2014, I was not overly impressed by it. However, seeing it at Hauser and Wirth in Somerset, it looks great. My description of it as an oversized bagel is not too far from the truth. It is, basically, an annular structure like a ring or a bagel, but it is far more interesting than that. Supported on rocks, the ring is not in one plane, but it undulates gradually. Irregularly shaped holes in its translucent skin provide intriguing views of Oudolf’s garden, which looks good in all seasons, and the surrounding hilly Somerset countryside.

A visit to Hauser and Wirth in Somerset makes a fine day out even if you have only a scant interest in contemporary art. The food served in the restaurant is of a high quality and not unreasonably priced. The buildings on the estate are lovely and the garden is hard to beat for its beauty.

July 14, 2021

Cows on the café

GUILAN IS A NEW cafe on the corner of Moscow Road and St Petersburgh Place in London’s Bayswater. I have walked past the building numerous times over the past more than 25 years, but until today I missed seeing something on the building.

Above the ground floor windows there are a number of

sculpted heads of cattle. I had never noticed these before.

On looking at a map produced in the 1950s, I discovered that

the building was then a dairy. An older map revealed that it was ‘The Aylesbury

Dairy’. A search on the Internet informed me that this building was the head

office of the company, which had another branch not far away. So, the cattle heads are a souvenir of the

building’s time as a dairy.

The new café in the former dairy is across the road from

Aghia Sofia, a Greek Orthodox church. The cafe is elegant and serves good

coffee and tasty pastries including a croissant flavoured with za’atar. I have

no idea from which dairy the milk is supplied to Guilan, but you can be sure it

is not the Aylesbury Dairy.

July 13, 2021

Candid

Godolphin House, Helston, Cornwall

Godolphin House, Helston, CornwallWhat can be seen

When you peer secretly through

A small hole in the wall.

July 12, 2021

Eating ice cream in an old harbour

CHARLESTOWN IN CORNWALL should not be confused with the dance named after Charleston in South Carolina, as it is just south of the Cornish town of St Austell. The latter, named after a sixth century Cornish saint, St Austol, was first associated with the tin trade and then with the China clay industry, which burgeoned after the material was discovered in the area by William Cookworthy (1705-1780) in the 18th century.

In 1790, only nine families lived in the tiny seashore settlement of West Polmear, a fishing village just south of St Austell. A year later, much was to change in this little place. For, in 1791, Charles Rashleigh, a local landowner, began building a dock at West Polmear, using designs prepared by the engineer John Smeaton (1724-1792), who is regarded by many as ‘the father of civil engineering’. By 1799, a deep-water harbour with dock gates had been constructed. The water level in this dock was maintained by water that travelled in a ‘leat’ (artificial channel) from the Luxulyan Valley, some miles inland. The harbour was fortified against the French with gun batteries.

Named after nearby Mount Charles, the Charlestown harbour was used first for loading boats with copper for export, and then later with China clay, also for exportation. Charlestown prospered during the rapid expansion of the Chana clay industry that lasted until the start of WW1. By 1911, the former fishing village, by then Charlestown, had a population of almost 3200. Between the end of WW1 and the 1990s, Charlestown continued to be a port for exporting clay, but rival ports and the use of ships too large to be accommodated, led to its gradual decline. Now, the lovely, well-preserved 18th century harbour has become a tourist attraction and a home for a few picturesque tall ships. It is also used occasionally as a film set.

We visited Charlestown on a warm, sunny, late June afternoon. After exploring for a while, we homed in on an ice cream stall, a small hut with a pitched roof tiled with slates, located above the northern end of the dock. After queuing for what turned out to be first class ice cream, we sat at a table near the stall to enjoy what we had ordered. It was then that I noticed that some of the tables and chairs were standing on a vast cast-iron plate, which was covered with geometric patterns and some words, which I examined. My suspicion that this plate had once been part of a weighbridge was confirmed when I noticed the words: “20 tons. Charles Ross Ltd. Makers. Sheffield”. I checked this with the ice cream seller in his stall. He told me that his stall had been the office of the officials who used the weighbridge and pointed out that there was another weighbridge nearby. I found this easily. Its metal plate bore the words: “Avery. Birmingham-England”, Avery being a well-known manufacturer of weighing machines. And the hut that used to be used by the officials now sells a range of snacks.

After eating our ice creams and examining the former weighbridge plates, a trivial thought flashed through my mind: by consuming ice cream at this stall, we were putting on weight at the weighbridge.

July 11, 2021

A recycled telephone kiosk

RURAL TELEPHONE BOXES (kiosks) are often used (re-purposed) to house AED defibrillators and small book libraries. Occasionally, they still contain coin-operated telephones. We were driving through rural Cornwall between Bodmin and Luxulyan, when we took a wrong turn and drove along a small lane. After making a three-point turn, I spotted an old telephone box partly covered with vegetation. Its original glazed door had been replaced by a wooden one that was quite out of keeping with the box’s elegant design. The present owner of the telephone box has been using this as the entrance to his or her garden. I was pleased to make find this quirky modification of an old telephone kiosk.

July 10, 2021

Gone for a barton in Bruton

BRUTON IN SOMERSET lies along the River Brue. Most of the old town is high above the river on its steep banks. Narrow passageways run along the steep slopes, connecting the High Street with the riverbank below. These steep passageways in Bruton are called Bartons. The word ‘barton’ means ‘farmyard’ in Old English. However, why these passages are called ‘bartons’ in Burton is a bit of a mystery despite the fact that there used to be farmsteads close to the town.

July 9, 2021

Sexey in Somerset

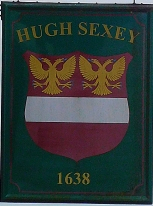

THE RIVER BRUE flows through the Somerset town of Bruton. In the Domesday Book (1086), its name was recorded as ‘Briuuetone’, which is derived from Old English words meaning ‘vigorously flowing river’. In brief, this small town is picturesque and filled with buildings of historical interest: a church; several long-established schools; municipal edifices; an alms-house; shops; and residences. On a recent visit, we drove past a Tudor building that was adorned with a crest labelled “Hugh Sexey” and the date “1638”. At first, I thought it was a sort of joke, rather like ‘Sexy Fish’, the name of a restaurant in London’s Berkeley Square. I walked back to the building after parking the car.

I looked at the sign, and my curiosity was immediately aroused. The crest bears a pair of eagles with two heads each, double-headed eagles (‘DHE’). Now, as some of my readers might already know, the DHE is a symbol that has fascinated me for a long time. This bird with two heads has been used as an emblem by the Seljuk Turks, the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires, Russia (before and after Communism), the Indian state of Karnataka, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, and some people in pre-Columbian America, to name but a few. In the UK, several families employ this creature on their coats-of-arms. These include the Godolphin, the Killigrew, and the Hoare families, to name but a few. Each of these three families has connections with the county Cornwall, which, through Richard, Earl of Cornwall (1209-1272) and King of the Germans, had a strong connection with the Holy Roman Empire, whose symbol was the DHE. Until I arrived outside the building in Bruton, Sexey’s Hospital, I had no idea about the existence of the Sexey family nor its association with the DHE.

Sir Hugh Sexey (c1540 or 1556-1619) was born near Bruton. He became royal auditor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I and later King James I, and amassed a great fortune. After his death, much of his wealth was used for charitable purposes in and around Bruton. Two institutions that resulted from his money and still exist today are Sexey’s Hospital, outside of which I first spotted the crest with two DHEs and Sexey’s School (www.sexeys.somerset.sch.uk/about-us/the-sexeys-story/). The school, which is now housed in premises separate from the hospital (now an old age home), was first housed in the same premises as the hospital.

According to the school’s website:

“…a two headed spread eagle is taken from the seal used by Hugh Sexey later in his life which can be seen on his memorial on Sexey’s Hospital …”

The article then considers the DHE (‘spread eagle’) as follows:

“Traditionally the spread eagle was considered a symbol of perspicacity, courage, strength and even immortality in heraldry. Prior to notions of medieval heraldry, in Ancient Rome the symbol became synonymous with power and strength after being introduced as the heraldic animal by Consul Gaius Marius in 102BC (subsequently being used as the symbol of the Legion), whilst it has been used widely in mythology and ancient religion. In Greek civilisation it was linked to the God Zeus, by the Romans with Jupiter and by Germanic tribes with Odin. In Judeo-Christian scripture Isa (40:31) used it to symbolise those who hope in God and it is widely used in Christian art to symbolise St John the Evangelist. An heraldic eagle with its wings spread also denotes that its bearer is considered a protector of others. Sexey’s seal and crest may have included the spread eagle to symbolise the family’s Germanic heritage.”

Some of this is in accordance with what I have read before, but I need to cross-check much of the rest of it, especially the Greek and Roman aspects. The final sentence relating to Germanic heritage seems quite sound, as the DHE was an important symbol in the Holy Roman Empire.

There is a sculpted stone bust of Sir Hugh Sexey in the courtyard of his hospital (really, almshouses), which was built in the 1630s. This portrait was put in its position in the 17th century long after his death. Above the bust, there is a carved stone crest bearing two DHEs, which was created by William Stanton (1639-1705) from London. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (‘DNB’):

“ Later in the seventeenth century a stone bust of Sexey, together with a coat of arms (that of the Saxey family of Bristol, with which he had no known connection), was placed over the entrance hall…”

The plot thickens as I now wonder whether the DHEs are related to the Sexey family or that of the above-mentioned Saxey family. A quick search of the Internet for the coats-of-arms of both the Sexey and the Saxey families revealed no DHEs except on crests relating to Bruton’s two Sexey foundations.

One family that was involved in the history of Bruton and whose crest bears the DHE is Hoare. They took over the ownership of the manor from the Berkely family in 1776. This is long after Hugh Sexey died and is therefore unlikely to be the reason that William Stanton included the DHEs on the crest above Sir Hugh’s bust. So, as yet, I cannot discover the history of the DHEs that appear all over Sir Hugh’s hospital and neither can I relate them to any other British family that uses this heraldic symbol. But none of this should mar your enjoyment of the charming town of Bruton.

July 8, 2021

From Cornwall to Poland and the Himalayas

THE CORNISH VILLAGE of St Kew, though small, is an extremely attractive place to visit. Its name derives from that of a Welsh saint called ‘Cywa’ who might have been the sister of Docca, who founded a monastery near the present village of St Kew. In the centre of the village, close to a bridge crossing a stream, there is a lovely pub, The St Kew Inn, which was built in the 15th century (www.stkewinn.co.uk/). We stopped there for much-needed liquid refreshment on a hot afternoon in late June 2021. Close to, and on higher ground than, the pub, there is another 15th century edifice, the parish church of St James.

The church contains much to fascinate the visitor including fine stone and wood carvings, remnants of pre-Reformation stained-glass, a carved stone with ancient Ogham script, a carved gravestone bearing the date 1601 and a depiction of a lady in Tudor dress, and wooden barrel-vaulted ceilings. All of this and more makes St James one of the loveliest churches we have seen in Cornwall. Although I was highly enchanted by all this antiquity, it was one modern memorial in the church that intrigued me most.

Themonument on the inside of the north wall of the church reads:

“Inmemory of Alison Chadwick-Onyskiewicz of Skisdon, St Kew. Born May 4th 1942. Artist and Mountaineer. She made the first ascentof Gasherbrum III. 26090 ft. And died on Mt Annapurna, Nepal, on 17thOctober 1978.”

Well,I was not expecting to find this when I entered the church at St Kew.

FromAlison’s obituary on the alpinejournal.org.uk website, I have extracted thefollowing information about her. She was born in Birmingham but spent herformative years in Cornwall. Whilst studying at the Slade School of Art atUniversity College, London, she became interested in mountaineering. Herclimbing experience began in North Wales, before gaining experience in the Alpsand rock faces in Devon and Cornwall.

In1971, she married a well-known Polish mountaineer, Janusz Onyskiewicz, who wasalso a mathematician and twice Poland’s Minister of National Defence (1992-1993and 1997-2000). In the 1980s, he was a spokesman for the Solidarity Movement. Alisonlived in Poland after she married him in Bodmin, Cornwall. She and Janusz were twoof the four members of the Polish expedition that conquered Gasherbrum III,which was at the time the highest yet unclimbed peak. The obituary notes:

“Alison’sclimbing ethics were always of the highest standard and on high mountains she wishedto compete with men on equal terms with the minimum of oxygen and Sherpa assistance.Perhaps it was for this reason that she chose to accept an invitation to jointhe 1978 American Ladies Expedition to Annapurna rather than accept a place on themore glamorous Franco/Austrian Expedition to Everest. On the Annapurnaexpedition Alison’s contribution was crucial, leading the ice-arete betweencamps 1I and III which proved to be the crux of the route. After the summit hadbeen reached on 15 October, Alison and Vera Watson were killed in a fall whilemaking a second summit bid.”

AlthoughJanusz was in the Himalayas 40 miles away from the scene of the fatal accident,news of it took two weeks to reach him.

So,that is, in brief, the story of the lady commemorated by an oval slate memorialin St James Church in St Kew. I have yet to discover where she was buried andwho placed the memorial in the church. Discovering this connection between StKew and the Himalayas was yet another delightful surprise that enhanced myenjoyment of the southwestern county of Cornwall.