Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 152

August 16, 2021

Poetry and a Chinese supermarket

GERRARD STREET IS THE HEART of London’s Chinatown. We often visit it to eat delicious dim-sum and other dishes at our favourite restaurant, The Golden Dragon, which has both indoor and covered outdoor dining spaces. One of our favourite dishes, which was introduced to us many years ago by my sister, is steamed tripe with chilli and ginger. It might sound off-putting, but, believe me, it tastes wonderful. Our visits to Gerrard Street always include a visit to Loon Fung, a Chinese supermarket. This well-stocked establishment bears a commemorative plaque that I only noticed for the first time today (12th August 2021). Partially hidden by a string of Chinese lanterns, it informs the passerby that the poet John Dryden (1631-1700) lived on the spot where we purchase pak-choi, chilli sauce, black bean paste, and a host of other ingredients for preparing Chinese-style dishes at home. I suspect that Dryden was unlikely to have ever come across any of these exotic ingredients back in the 17th century.

According to the English Heritage website (https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/…/blue…/john-dryden/):

“Dryden lived at 44 Gerrard Street with his wife Elizabeth (c. 1638–1714) from about 1687 until his death in 1700. His years there were difficult: his conversion to Catholicism in about 1685 meant that he was unable to take the oath of allegiance after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. As a result he lost his position as Poet Laureate, one he had held for 20 years. He found himself in financial difficulties but remained highly active in London’s literary world.Dryden usually worked in the front ground-floor room of the house, and it was here that he completed his last play, Love Triumphant (1694), the poem Alexander’s Feast, or, The Power of Musique (1697) and translations such as The Works of Virgil (1697). In the preface to the latter, Dryden likened himself to Virgil in his ‘Declining Years, struggling with Wants, oppress’d with Sickness’…

… Number 44 was built in about 1681 and re-fronted in 1793, before being redeveloped in about 1901. At the same time number 43 was demolished, a deed described in the press as ‘a hideous and wonton act of vandalism’ …

… The plaque, though damaged, was immediately re-erected on the new structure. It is unique among surviving Society of Arts plaques in its colour – white, with blue lettering.”

Well, I can add nothing to that informative quote. So, ext time you wander along Gerrard Street do look for this and other reminders of the area’s history. It was a place where several other well-known writers and artists resided several centuries ago.

August 15, 2021

The gardener’s enemy

August 14, 2021

Bulky rather than beautiful

DURING THE LAST YEAR or longer, we have visited plenty of ‘stately homes’ in England. Many of them are very fine works of architecture.Today, we visited Blenheim Palace for the second time in 12 months., It was built for the first Duke of Marlborough and is still home to some of his descendants.

Of the many grand homes that we have seen during our travels, Blenheim impressed me far, far less than many of the others. It is impressive in its bulkiness but, for me, it lacks the finesse that characterises so many of the other aristocratic homes we have visited.

PS: To be fair, Blenheim was not completed as originally planned because at some stage the funds for its construction became dramatically reduced.

August 13, 2021

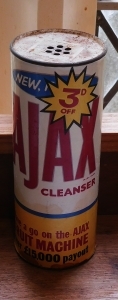

Removing stains, not memories

August 12, 2021

Calling the world

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, the family possessed a radio, which could receive long wave, medium wave, and short-wave signals. It was made by Pye, contained in a dark brown wooden cabinet, and took several minutes to ‘warm up’ before anything could be heard from it. It was faced with glass screen behind which there was a list of radio stations and a vertical cursor that could be moved across the list to tune into different stations. The stations listed were, to my young mind, quite exotic. They included places such as Berlin, Budapest, Beromunster, Moscow, Prague, Monte-Carlo, Leipzig, Hilversum, Vienna, Sofia, Cairo, and Luxembourg. One of the places on the tuning screen sounded far less exotic to me: Daventry. I knew that this place was somewhere in the English Midlands, and that gave it less appeal to me than places further afield and across the sea.

Recently, we spent a couple of nights near Rugby in Warwickshire. After leaving it to travel eastwards, we noticed that we would be passing through Daventry, and decided to stop there for breakfast. Prior to our arrival in that small town in Northamptonshire, I believed that it would turn out to be a place of little interest apart from the fact that I remembered having seen its name on our old radio back home in the early 1960s. How wrong I was to have pre-judged Daventry so harshly.

We parked next to a modern shopping centre, attractively arranged around an open space in which people were enjoying refreshments at outdoor tables and chairs. This contemporary shopping precinct is close to the High Street, which runs from Market Square to Tavern Lane. This thoroughfare is rich in historic buildings.

Overlooking Market Square is the former Daventry Moot Hall, an 18th century building, and beyond it on a slight elevation is the Holy Cross Church. This neo-classical style church was built between 1752 and 1758 to the design of David Hiorne (1715-1758) of Warwick. Not only does it resemble London’s St Martin-in-the-Fields, but on a smaller scale (and with a far smaller portico), but also many churches built by the British in India during the 18th and 19th centuries. Seeing the church in Daventry reminded me of the far larger St John’s Church in central Calcutta and the Danish church at Serampore on the River Hooghly. Unfortunately, the church in Daventry was not open when we visited it.

At the other end of the High Street, where it continues as the narrower Tavern Lane, there is a curious building with gothic revival features and crenellations. We asked an elderly man about the building and he told us that it used to be the BBC Club. It was then that I remembered that Daventry had connections with radio broadcasting. I recalled seeing the place’s name on our old radio at our home in northwest London. Our informant reminded us that for many years the transmitters near Daventry carried news and other broadcasts from Britain to the rest of the world.

On the 27th of July 1925 at 730 pm, the BBC began broadcasting from its new station at Daventry. At first, these transmissions could be received on crystal radio sets within a 250-mile radius of a circle with Daventry at its centre. Soon after this, broadcasts could be received far further afield. This was further augmented when the BBC installed much more powerful transmitters in about 1927. By the end of WW2, Daventry was transmitting the ‘highbrow’ Third Programme (now, ‘Radio 3’) broadcasts.

In December 1932, Daventry began transmitting programmes to a world-wide audience on the Empire Service. As the threat of war increased during the 1930s, Daventry started transmitting regional services such as The Arabic Service (in Arabic) and The Latin American Service (in Spanish). After WW2 broke out, there were broadcasts in many other foreign languages. Some monitoring of foreign broadcasts was also carried out in Daventry.

During the Cold War that followed the end of WW2, Daventry was involved in the transmission of programmes to people living on the Soviet side of the so-called Iron Curtain. Until its closure in 1992, the radio station and its transmitters at Daventry were continually updated. One of several reasons for its closure was the end of the Cold War following Gorbachev’s leadership of the USSR and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Now, returning to the gothic revival building at the end of Daventry’s High Street, here is what Norman Tomalin, who worked at Daventry and has written a history of its radio station (www.bbceng.info/Books/dx-world/dx-wor...), has to say about it:

“For the many thousands of BBC staff who briefly came to Daventry, the BBC Club … was home from home. It provided a central cosy meeting place, a break from the digs, a bar, billiards, table tennis, and photographic rooms and on the top floor, pride of place, a much treasured amateur radio transmitter. Call sign 5XX”

‘5XX’ was the call sign of the first transmitter at Daventry. It was superseded by another ‘5GB’ in 1927.

Our elderly informant told us that he remembered that broadcasts from his hometown used to begin with the words: “Daventry Calling The World”. In his book “Daventry Calling”, Tomalin wrote that the very first broadcast from Daventry began with the words: “Daventry Calling”, for back in 1927, it was not the world that could receive the programmes, only people in the UK.

I wonder how many of the people who listened to broadcasts from Daventry all over the world had any idea where the town was and if they did, did they wonder if it was as great a city as many of the others that appeared on radio tuning dials.

August 11, 2021

A country church with a thatched roof

SNAPE MALTINGS ON Suffolk’s River Alde is a famous venue for music (mainly) and the other arts. It is the home of the Aldeburgh Festival, started in 1948 by the composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) and his partner, the singer Peter Pears (1910-1986). We have yet to attend a concert there, but we have eaten a fine lunch in its beautifully designed River View eatery. From the Maltings, you can enjoy views across the water meadows and if you look carefully enough, you can spot the tower of the Church of St Botolph in the tiny village of Iken across the river.

St Botolph, who died in about 680, is believed to have brought Christianity to Iken in about 654. He is the patron saint of boundaries, and, because of this, also of trade and travel. The present church dedicated to him is curious because its nave has a thatched roof. It was preceded by a minster built by Botolph but destroyed by the Danes in the 9th century. In 870, a Saxon timber church was constructed. This has also gone. It was replaced by a stone edifice, the beginning of what we can see today.

The Norman flint-rubble nave of the current church was built between about 1070 and 1110. The western tower, also with flint and other masonry was constructed soon after Robert Geldeny and William Baldwyn bequeathed money for its construction in 1450 and 1456 respectively. During the Reformation in the 16th century, various changes were made to the church’s interior to conform with the restrained liturgical requirements of the Reformed Church. This would have included whitewashing over colourful frescoes and destruction of stained glass and other decorative features. By the 19th century, the church was becoming somewhat dilapidated. Between 1850 and 1860, restoration works were undertaken. A new chancel was constructed in the style of the early 14th century on the foundations of the original mediaeval chancel. It was designed by John Whichcord (1790-1860) of Maidstone in Kent.

In 1942, during WW2, the whole of the population of Iken was evacuated so that the area could be used for battle training. The church was also closed. It reopened in 1947 after the villagers returned to Iken. During the 1950s, they did much work to improve the condition of their church. In 1968, sparks from timber being burnt nearby set fire to the thatched roof of the church. The nave was badly damaged, but the chancel survived. Today, visitors to the church would not be able to imagine that it had suffered such a conflagration, so well has it been repaired.

Inside the church, several things attracted my attention. The most fascinating is the Saxon cross shaft in the northwest corner of the nave. Covered with bas-relief Celtic-style carvings this 4 ½ foot fragment of a stone cross (possibly, originally 9 feet in length) was created either in the 9th or 10th century. Near to this, there is a lovely octagonal stone font, which is 15th century. It is covered with superb carvings, some of which depict the emblems of the four Evangelists. These are separated from each other by angels. The wooden altar reredos, a panel behind the altar, was carved by Harry Brown of Ipswich and dedicated in 1959. It bears a bas-relief of The Last Supper, which Mr Brown based on the famous painting of that occasion by Leonardo da Vinci. I have mentioned a few of the items within the church that I found interesting but there is plenty more to see, all listed in an informative booklet on sale in the church.

From the boundary of the graveyard surrounding this lovely church, you can catch glimpses of the River Alde, which flows nearby. Visitors to Snape Maltings should spare some time to visit the church at Iken. It is so nearby yet feels so far away.

August 10, 2021

A hospital without patients

BROTHER PETER IS one of six retired ex-servicemen who reside at The Lord Leycester Hospital, one of the oldest buildings in the town of Warwick apart from its famous, much-visited castle. He explained to us that the word ‘hospital’ in the name refers not to what we know as a medical establishment but to a place providing hospitality. The men, who reside in the Hospital are known as the ‘Brethren’.

The Hospital is contained in an attractive complex of half-timbered buildings that were erected next to Warwick’s still standing Westgate in the late 14th century. They are almost the only structures to have survived the Great Fire of Warwick that destroyed most of the town in September 1694. The buildings and the adjoining chapel that perches on top of the mediaeval Westgate were initially used by the guilds of Warwick, which played a major role in administering the town and its commercial activity. The ensemble of edifices includes the mediaeval Guildhall in which members of the guilds carried out their business. Between 1548 and 1554, it was used as a grammar school.

In 1571, Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (1532-1588), who lived in nearby Kenilworth Castle, was asked by the queen to clear the streets of Warwick of ailing, infirm, and disabled soldiers, by establishing a refuge (i.e., ‘hospital’) to shelter them. It is said that Dudley persuaded the town’s officials to give him their Guildhall to be used for this purpose. This ended the guilds’ use of the complex of mediaeval buildings, now known as Lord Leycester’s Hospital.

Initially, Dudley’s hospital provided accommodation for The Master, a clergyman, and twelve Brethren, poor and/or wounded soldiers, and their wives. According to the excellent guidebook I bought, the original rules of the hospital include the following:

“That no Brother take any woman to serve or tend upon him in his chamber without special licence of the Master, nor any with licence, under the age of three-score years except she be his wife, mother, or daughter.”

To accommodate them, modifications of the interiors of the buildings had to be made. Brother Peter, with whom we chatted, is one of the current Brethren. He introduced us to another of his fraternity, a young man with a scarred head, who had survived an explosion whilst serving in Afghanistan.

Dudley’s arrangement survived until the early 1960s, when the number of Brethren was reduced to eight. By this time, the Master was no longer recruited from the clergy but from the retired officers of the Armed Forces. What is unchanged since Dudley’s time is his requirement, established in an Act of Parliament (1572), that the Brethren must attend prayers in the chapel every morning. They recite the very same words chosen by Dudley when he established the hospital.

We did not have sufficient time to take a tour of the buildings that comprise the hospital, but we did manage to enter The Great Hall, which now serves as a refreshment area for visitors. This large room has a magnificent 14th century beamed timber ceiling made of Spanish chestnut. It was here that King James I was entertained and dined in 1617, an event lasting three days. We were also able to catch a glimpse of the Mediaeval Courtyard, which is:

“… one of the best preserved examples of medieval courtyard architecture in England.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Leycester_Hospital).

The Lord Leycester Hospital is less well-known than the nearby Warwick Castle, which has become something of a costly ‘theme park’. However, the hospital is a far more interesting place to visit, However, you will need to go there before the 23rd of December 2021, when it will be closed for restoration for quite a lengthy period.

August 9, 2021

An isolated Anglo-Saxon chapel

A FEW MONTHS AGO, we paid a brief visit to Mersea Island, which is off the coast of Essex. While we were wandering around on the island, we spoke with a man, who recommended that we visit the isolated chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall, which is not far from Bradwell-on-Sea, also on the coast of Essex. He thought that we would enjoy its tranquillity and the beauty of its surroundings. In early August 2021, we drove beyond Bradwell-on-Sea to a carpark, which is 785 yards west of the chapel known as St Peter-on-the-Wall. The building is about 300 yards west of the east coast of Essex on the Dengie Peninsula, the southern lip of the mouth of the River Blackwater. The chapel stands on a hill overlooking the surrounding coast and countryside.

Winding the clock back to the time when the Romans ruled Britain, we find that there was a fort named ‘Othona’ near the site of the chapel. It was one of a series of Roman forts created to protect Britain from Saxon and Frankish pirates, possibly built by a Count of the Saxon Shore, a Roman official, named Carausius, who died in 293 AD. A Roman road ran up to the fort, connecting it with places further inland. During the 7th century, the Romans having left Britain, an Anglo-Saxon holy man, Cedd by name, landed at Othona in 653.

Cedd (born c620) was one of four brothers. He had a religious upbringing and education in the monastery set up by Saint Aidan (c590-651) at Lindisfarne on the coast of Northumbria. Cedd became a missionary. After successes in the Midlands, he was invited by Sigbert, King of the East Saxons, who reigned in Essex, to bring Christianity into the area. Cedd sailed from Lindisfarne and landed at what was the ruined fort at Othona. He moved north later in life and died in 664 (of the plague) near Lastingham in Northumbria, where he had founded another religious establishment.

Cedd’s first church at Othona might well have been wooden, but soon he built one of stone, of which there was plenty lying about in the ruins of the fort. His stone church is built in what was then the style of churches in Egypt and Syria. Apparently, Celtic Christians, such as Cedd, were influenced by this style. Building a church in the ruins of a Roman fort mirrored that which had been built in the ruins of a fort by St Antony of Egypt. The location of the former fort on the Roman road might have appealed to Cedd as it would have facilitated ‘spreading the word’ inland.

The church that Cedd built used to have a chancel and possibly other parts, as it was part of a monastic complex based near Bradwell. Cedd’s church, St Peter’s, simple as it was and is still, can be considered the first cathedral to have been built in Essex. It is considered unlikely that the monastery Cedd created near Bradwell survived the Danish invasions. Soon after Cedd’s death, Essex was incorporated into the diocese of London and St Peter’s became a minster, the chief church in the area. When the parish church of St Thomas was built in Bradwell-on-Sea, St Peter’s became relegated to being a ‘chapel of ease’. Services were held three times a week there until at least the end of the 16th century. Sometime after this, the chancel was pulled down; the church was left standing as a navigation beacon; and the building was repurposed as a barn. As a barn it remained until the early 20th century, when the church was reconsecrated and restored in 1920.

The church is still in use. Services are held there under the auspices of the nearby Othona Community, based nearby at Bradwell-on-Sea. At present, services are held on Sunday nights in July and August at 6.30 pm.

We walked across the fields to St Peter-on-the-Wall, which is one of Britain’s oldest still standing and working churches. After some difficulty, we managed to open the one door to the church. We entered the building’s simple and peaceful interior. A colourful crucifix, created by Francis William Stephens (1921-2002) hangs high up on the east wall. St Cedd is depicted praying at the feet of Jesus on The Cross. The supporting stone of the simple stone altar has three fragments embedded in it. One of them was a gift from Lindisfarne, another from Iona, and the third from Lastingham. The altar was consecrated in 1985. Apart from a circle of chairs for congregants and a timber framed ceiling, there is little else in the church apart from a feeling of tranquillity, which can only be experienced by visiting this charming place. The man at Mersea Island, who suggested that we visit St Peter-on-the-Wall, did us a good turn.

August 8, 2021

Watch out! Snakes about!

Near Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex

Near Bradwell-on-Sea, EssexMind the adders

One bite by these fine serpents

Could subtract from your life

August 7, 2021

He paid with spears and swords

MALDON IN ESSEX is best known for the sea salt, prized by cooks and gourmets, which is produced nearby. The town perches on a hill overlooking a marshy inlet of the River Blackwater and the River Chelmer, after which Chelmsford is named, flows through a lower section of the place. We have visited Maldon several times over the last 18 months and always walked along part of its promenade that provides attractive views over the marshes and streams watered by the Chelmer and the Blackwater. However, it was only during our most recent visit (August 2021) that we walked the entire length of the promenade to its end point, which is out of sight of the town. The promenade ends abruptly, a bit like the end of a pier. There at the furthest extremity of the walkway, there is a tall statue. It depicts a man in a helmet, brandishing a sword in his right hand, holding a circular shield in his left, and looking out to sea.

The statue overlooking the sea is a sculpture of Byrhtnoth, Ealdorman of Essex, an Anglo-Saxon aristocrat or high official, who lived during the reign of Ethelred the Unready (c996-1016). Byrthnoth died during the Battle of Maldon on the 11th of August 991. The battle was fought by the Anglo-Saxons against an army of Viking invaders. It is said that before the battle, the Vikings offered to sail away if they were paid with gold and silver. Byrhthnoth was recorded as replying that he would only pay the attackers with the tips of his men’s spears and the blades of their swords.

After the battle, the then reigning Archbishop of Canterbury, Sigeric the Serious, advised Ethelred to pay off the Vikings instead of continuing the fight against them. According to an article on Wikipedia, this payment of 3,300 kilogrammes of silver was the first example of the so-called Danegeld in England. This was a ‘tax’ paid to the Vikings in exchange for them desisting from ravishing the territory which paid it.

So, the statue depicts a participant in a defeat of the English (Anglo-Saxons), and much loss of life amongst the Viking invaders. It was created by John Doubleday (born 1947) and unveiled in 2006. Byrhtnoth stands on a tall cylindrical base decorated with bas-relief depictions of scenes of life in the 10th century and moments during the Battle of Maldon. A plaque embedded into the promenade’s pavement near the statue gives more background to the historical event. It reads:

“Byrthnoth, represented by the figure standing on this monument, was the principal voice in rejecting the policy of appeasement which dominated the court of King Ethelred in the closing years of the 10th century. The leading military figure of his time; he was probably aged 68 when he confronted the Vikings at the battle of Maldon. He surrendered his life in defence of the people, religion and way of life represented in the lower relief panel of the column. Above it you will see aspects of the battle in which he died. Around the base is a quotation from his final prayer as recorded in the surviving fragment of the poem ‘The Battle of Maldon.’”

The poem, mentioned above, was written in Old English. However, much of it has now been lost.

Apart from the statue, Maldon has much to offer the visitor. Along the quayside, there are several old Thames Barges with their maroon/brown sails and a lovely pub, The Queen’s Head Inn. Church Street climbs from the riverside to the High Street which is lined by several old houses; a disused church, now a museum; an attractive parish church; and plenty of decent places to eat and drink. Within easy reach of London, this is a delightful place for a day out or as a base for exploring rural Essex.