Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 148

September 25, 2021

Only the name is the same

AFTER A SUNNY DAY spent at Whitby in North Yorkshire, we stopped for a drink at sundown in a small pub for a pre-prandial alcoholic beverage. Behind and slightly above the pub, we could see a well-maintained 12th century parish church with later modifications and a square tower. Below the pub, a narrow stream, lined with bushes and trees, ran alongside the main road. Apart from the infrequent passing car, the place was silent except for some pleasant birdsong. From where we sat on the terrace of the hostelry, we could see a small, sloping village square with a simple war memorial, some parked cars, and a small post box. At first, I did not realise where we had stopped. Then, I noticed that the village is called Kilburn.

Kilburn, North Yorkshire

Kilburn, North YorkshireThere is another Kilburn about 215 miles south of the lovely village where we stopped for an evening drink. The latter is in North Yorkshire and the place with the same name many miles south of it is in north London. Apart from sharing the same name, London’s Kilburn is anything but rustic and peaceful, as many Londoners will know. London’s Kilburn is not really picturesque in conventional people’s eyes; it might appeal to lovers of urban sprawl. It is a crowded metropolitan area with much commercial activity and a racial profile infinitely more diverse than that of the village in North Yorkshire.

I am not sure which of the two Kilburns is the oldest. North Yorkshire’s village was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 and named ‘Chileburne’. London’s Kilburn was a settlement on an ancient Celtic route, a track between the places now known as St Albans and Canterbury. A priory was constructed on a stream that flowed through where London’s Kilburn now stands. The stream was known variously as ‘Cuneburna’, ‘Kelebourne’, and ‘Cyebourne’.

Whatever the origins of these two Kilburns, I know which of them is the place where I would prefer to linger in front of a glass of bitter.

September 24, 2021

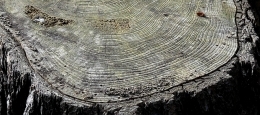

Rings of life

September 23, 2021

The hole story: Barbara Hepworth in Wakefield

I VISITED BARCELONA in the late 1960s. One of the sights I saw was a museum dedicated to Pablo Picasso. Before entering that place, the artist’s works somewhat puzzled me. In the museum, there were some of Picasso’s earliest paintings. They were straightforward rather than abstract, and extremely well executed. The artist’s talents were immediately obvious. As I moved from room to room, the works on display became increasingly abstract. By seeing his progression from figurative to abstract, I began to appreciate his greatness as an artist, and I began to understand why he is regarded as a brilliant creator by many people. By the time I had finished looking around the museum, I had been converted from being sceptical about Picasso to becoming yet one more of his fans. More recently, I saw an exhibition showing the artistic development of Roy Lichtenstein from his earliest to his latest creations. No longer was he just a creator of entertaining pictures based on American comic strips, but I could see that he was an artist of great competence. Like the foregoing examples, a visit to the Cartwright Hall Museum in Bradford and seeing some of David Hockney’s earliest works also enhanced my appreciation of this highly prolific visual artist.

Bradford in Yorkshire is not far from the city of Wakefield, where Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) was born. She was baptised in the city’s fine cathedral. Until today, I had mixed feelings about Hepworth’s works. There are some that I like very much, including a Mondrian-like crucifix at Salisbury Cathedral and a Naum Gabo inspired work attached to the eastern side of the John Lewis shop on London’s Oxford Street. Also, I have enjoyed visits to Hepworth’s studio and garden in Cornwall’s St Ives. However, as beautifully executed as her works are, I did not become terribly keen on her artistic output until today, the 18th of September 2021.

What converted me and increased my appreciation of Hepworth as an artist was today’s visit to the Hepworth Wakefield Museum. We arrived to discover that for the time being the whole museum is filled with works by Hepworth, beginning with her earliest and ending with her latest. The temporary exhibition, “Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life”, continues until the 27th of February 2022, and should not be missed.

As with other abstract artists, such as Picasso, Hepworth began learning the basics of figurative representation. Her earliest carvings and drawings were created superbly competently but give no hint of which directions her creative output was soon to follow. Had she not developed any further, she would have been regarded as a skilled, if not too exciting, sculptor. However, Hepworth soon became involved artistically, and in one case maritally, with leading artists of the twentieth century. Contact with them and their ideas can be detected in some of the works she created as she moved from purely representational to highly abstract. It was particularly interesting to see a small carving with a hole in it, the first of her many works to have holes in them. The idea of the holes is to allow light to flow through her sculptures. It was not only other artists who inspired Hepworth’s creation but also the forces of nature, which unconsciously sculpt rocks, trees, and other natural features in the landscape.

It was interesting to see the life-size prototypes of some of Hepworth’s works I have admired in the past. It was wonderful, for example, to be able to get close to the full-size model sculpture which is now high up on the wall of John Lewis in Oxford Street.

Once again, seeing a collection of works illustrating the progression of an artist’s output from student days until the achievement of fame and beyond has helped me to increase my appreciation of an artist about whom I had some reservations. Today’s visit to the Hepworth Wakefield has moved Barbara Hepworth a long way up my ladder of great artists and removed any doubts I had about her works.

Finally, here is something that intrigues me. Hepworth, like Picasso and also my late mother, had what might be described as traditional basic artistic training, just like the European and western artists who created during the many centuries before the 20th, yet all three of them (and many others) moved from expressing themselves with figurative works to abstract creations. However, unlike the artists who flourished before the latter parts of the 19th century and never strayed into the world of artistic abstraction, those who created during after the late 19th century (including the Impressionists) strayed away from the purely figurative/representational. Why this happened is no doubt the subject matter of much art historical literature, which I have yet to read. As I wrote the previous sentence, it occurred to me that the move towards abstraction (and other forms of art that do not appear to give the viewer a straightforward recreation of nature) coincided with the advent of photography. The photograph can give the illusion of being a true image of the world, leaving the artist to explore other more imaginative representations of what he or she has seen.

September 22, 2021

A pair of converging railway viaducts

THERE IS A FASCINATING pair of railway viaducts at Chapel Milton, near Chapel-en-Frith in the Peak District. Constructed in about 1860 and then 1890, the viaducts support a place where two railway lines diverge. The viaducts, which join each other at a bifurcation were built at different times as the dates suggest. One of the arcades consists of 13 arches and the other of 13.

Allow Wikipedia to explain:”The Midland Railway opened a new line via Chapel-en-le-Frith Central and Great Rocks Dale, linking the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midland Junction Railway with the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, in 1867, giving it an express through route for the first time between Manchester and London … The eastern section, essentially a second, mirror-image viaduct in an identical style, was added in 1890 to allow trains to travel between Sheffield and the south via Buxton and the Midland’s own line.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chapel_Milton_Viaduct)

September 21, 2021

Draining a canal

EVERY NOW AND THEN, a canal needs repairing. For example, it might have sprung a leak either in its retaining walls or in its clay bottom. In such circumstances and no doubt others, the repair work can only be carried out if the canal is emptied of water, a tall order in a canal that might be many miles in length. Recently, we were walking along the towpath of the Macclesfield Canal, which links Marples Lock on the Peak Forest Canal with Hardings Wood Junction on the Trent and Mersey Canal, when we spotted something that we had never noticed before whilst walking along a canal towpath.

What we saw was a pile of sturdy wooden planks, each with two metal handles attached to their narrowest edges. They looked quite modern. We asked a man, who was walking his dog, about the planks. He explained that they were used to block both ends of a section of canal between two consecutive bridges. When these barricades are lined with plastic sheeting, the water between the two barricades can be drained from the part of the canal between the two waterproofed wooden barriers, Then, work can be carried out on the drained stretch of the canal. The planks are known as ‘stop planks’

Our informant pointed out notches carved in the stonework near to a bridge. The notch is opposite another identical one across the canal. It is into these pairs of notches that the planks we had noticed ate inserted to create a dam, I regard myself as being quite observant, but I have never seen or noticed either this kind of notch or the wooden planks for inserting in them during many long walks along canals in other parts of England. Maybe, they are common, but until we walked beside the Macclesfield Canal, I had never seen them before, Maybe, this is because other methods of damming (see: https://www.rchs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/OP-128.pdf) are also employed in addition to that which we spotted on the Macclesfield Canal at Bollington in Cheshire.

September 20, 2021

Books in Buxton

ONE OF THE SEVEN WONDERS of the Derbyshire town of Buxton has to be Scrivener’s bookshop. Located on the town’s High Street, this shop displays books on five floors including the basement. Many, but by no means all, of the books are second-hand (pre-loved). At first sight, the books seem to be crowded together in no particular order, but the reverse is true: they are arranged systematically rather than chaotically.

The books are far from being at bargain prices, but they are priced fairly, not outrageously. Those of you, who know my addiction for acquiring books, will be relieved to know that I purchased only two volumes. There were plenty more that I might have been tempted to buy had I not already embarked on on a project of carefully reducing the number of books in my possession.

September 19, 2021

Drama in the Peak District

WE DROVE TO BUXTON from Macclesfield, crossing part of the Peak District, which was shrouded in dense morning mist despite it being mid-September. The town, once an important spa, is delightful. Its centre is rich in Victorian buildings, as well as some 18th century edifices, such as The Crescent, now a hotel. In appearance, the Crescent, which was built for the 5th Duke of Devonshire between 1780 and 1789, rivals the fine crescents found in Bath. Another notable structure in Buxton is The Dome, now a part of the University of Derby. This huge dome was built to cover a stable block for the horses of the 5th Duke, which was constructed between 1780 and 1789 to the design of John Carr (1723-1807). The dome itself, which is 145 feet in diameter and larger than those covering Rome’s Pantheon and St Peters, was added between 1880 and 1881, by which time the building it covered was being used as a hospital. It is the second largest unsupported dome in the world.

In common with great cities such as Vienna, Milan, Paris, Manaus, London, New York, and Sydney, tiny Buxton also can boast of having an opera house. Located next to a complex of Victorian glass and iron structures including a plant conservatory and the Pavilion with its attached octagonal hall, the Opera House was designed by the prolific theatre architect Frank Matcham (1854-1920) and first opened its doors to an audience in 1903. Live theatrical performances, not confined to opera, were held there regularly until 1927, when it became a cinema. Between 1936 and 1942, the Opera House, although then primarily a cinema, hosted annual summer theatre festivals, two of which were in collaboration with Lillian Baylis (1874-1937) and London’s Old Vic Theatre company (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buxton_Opera_House). In 1979, the theatre was restored, and an orchestra pit added. Since then, the Opera House puts on a programme of live performances, which include a little bit of opera. Unfortunately, during our visit to Buxton, the auditorium was closed, but we did manage to enter the lovely foyer with its mosaic-bordered floor and its ceiling painted with a scene evoking the style of 17th and 18th century painters.

The Opera House, the Crescent and the Pump Room opposite it, and The Dome, all add to the charm of Buxton. They are all close to a lovely park, through which the River Wye (not to be confused with the river with the same name in Wales) runs through. Buxton’s Wye flows into the North Sea via the River Humber. High above the park, runs the High Street, where we stumbled across a fabulous bookshop, Scrivener’s, which boasts five floors packed with books, many of them second-hand or antiquarian. So, if it is literature (fiction and non-fiction) rather than drama that appeals to you, this shop is a place that must be visited.

It was well worth winding our way across the hills to Buxton through the low clouds, which made visibility very poor. The town is filled with interesting things to see, some of which I have described above. However, it was the Opera House that intrigued me most. Had it been given a name other than Opera House it might not have fascinated me quite as much. That a town or city can boast an opera house, gives the place a certain ‘caché’ that places, which do not possess one, lack.

September 18, 2021

Travelling abroad at last

WE ARRIVED IN ENGLAND from India on the 27th of February 2020. Because of the covid outbreak, we had not left England until today, the 13th of September 2021. Some, especially those who live there, regard Cornwall as being another country, rather than part of England. We have visited that southwest county of what most people regard as England, since we arrived back from England. So, it would be pushing things if we said that we went abroad to Cornwall,

Today, we travelled abroad, leaving England for a few hours. To reach our destination we did not have to take covid tests or show evidence of double doses of vaccine or, even, show our passports. However, leave England we did. We crossed the River Severn to leave England and enter Wales. Crossing the Severn Bridge on the M48 did not require us to pay a toll as used to be the case, as the crossing is now free of charge. A few years ago, a toll was charged for crossing into Wales, but no longer; it has been abolished.

Tintern Abbey

Tintern AbbeyWell, I hear you say, Wales is not exactly ‘abroad’, but when one has not left England for over 18 months, it will do as ‘abroad’. Wales has its own parliament and most signs, be they on the road or elsewhere, are bilingual (English and Welsh) and, if you are lucky, you will meet a speaker of the Welsh language. To us, crossing over into Wales, after so many moths without foreign travel, felt like going abroad.

We drove along the beautiful Wye Valley and stopped at the attractive ruins of the former Cistercian Tintern Abbey (Abaty Tyndyrn in Welsh), the first ever Cistercian foundation in Wales. At the ticket office, I expressed my joy at being abroad after so many months, and the cashier said to me in a gently Welsh accent:

“I like your style.”

We have visited Tintern Abbey (founded 1131) many times in the past and each time it has been a wonderful experience. Today was no exception. Set in a wooded valley, the ruins of the gothic buildings look great against the background of trees with dark green foliage. After spending about an hour in Tintern, we drove along roads which were mainly in Wales but occasionally crossed the border into England. When we reached Wrexham (Wrecsam in Welsh), we headed off north and east into England, our trip abroad having been completed.

September 17, 2021

A new sculpture at Wells Cathedral

New metal sculpture by Antony Gormley at Wells Cathedral

New metal sculpture by Antony Gormley at Wells CathedralAmong the carvings

At venerable Wells Cathedral

Stands a novice

The sculptor Antony Gornley (born 1950) has added a new artwork (made of metal) to an empty niche on the west facade of Wells Cathedral in Somerset, England

September 16, 2021

A lonely chimney

A SOLITARY CHIMNEY stands in the middle of East Harptree Woods in the Mendip Hills of Somerset, not far from Bristol and Bath. This tall, not quite vertical, chimney and the surrounding uneven landscape is all that remains of the local tin and zinc mining activities in the area. Known as Smitham Chimney, this was built in the 19th century and was the exhaust for the toxic fumes created by the furnaces smelting lead-bearing materials. The unevenness of the surrounding area, now richly populated with a variety of trees, was caused by the pits and spoil heaps created during the era of mining activity. The chimney was built in 1867 and by 1870, the East Harptree Lead Works Co Ltd were producing about 1000 tons of lead per year (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smitham_Chimney,_East_Harptree).

Smitham Chimney

Smitham ChimneyToday, the chimney stands amongst a fine collection of trees including conifers and birches, all growing in a sea of ferns and other bushes. Much of the woodland is mossy. Maintained by Forestry England, the Mendip Society, and Somerset County Council, the woodland has good, fairly level paths, easy on the feet. The place and its industrial archaeological feature make for a pleasant and interesting short excursion.