Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 144

November 17, 2021

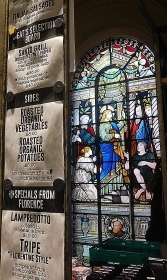

Gin and tonic by the pulpit

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE DIED in captivity on the tiny island of St Helena in the south Atlantic. While he was imprisoned on the island, Lieutenant General Sir Hudson Lowe (1769-1844) was the Governor of St Helena. He was buried at St Mark’s Church in North Audley Street in London’s Mayfair, where a commemorative plaque can be found by the main entrance. St Mark’s was built in the Greek Revival Style in 1825-28, designed by John Peter Gandy (1787-1850). In 1878, the church architect Arthur Blomfield (1829-1899) made considerable alterations to its interior including adding a timber vaulted ceiling over the nave.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the size of St Mark’s congregation diminished significantly. In 1974, the church was made redundant, and this is how it remained until 1994, when the church was used by The Commonwealth Christian Fellowship. It continued to serve this group until 2008. After that, it was used as a venue for occasional events. In about 2019 after a 5 million Pound restoration programme, the church underwent a surprising reincarnation.

After passing beneath the grand portico supported by two columns topped with ionic capitals, one enters the church’s large vestibule. Since 2019, this has become a marketplace selling upmarket Italian delicatessen goods. Entering the body of the church is rather like taking part in a Fellini film. The floor of the nave is filled with tables and chairs and people drinking and dining. The side aisles, north and south, contain several kitchens, preparing and serving a wide variety of foods, from Turkish to Thai. On the north side of the chancel, just behind the neo-gothic stone pulpit, there is a gin bar, and facing it on the south side of the chancel, there is another bar providing alcoholic refreshments. Look upwards and you can admire the splendid timber roof supports. The wide gallery surrounding the nave at the first-floor level is home to more food stalls, each offering tempting looking fare at not unreasonable prices, especially by local Mayfair standards.

In 2019, the church became home to a branch of Mercato Metropolitano, whose first venture was converting a 150,000 square foot disused railway station in Milan during the 2015 World Expo in that Italian city. The idea of the company was:

“The development of the first Mercato Metropolitano was carefully planned to retain the site’s original appearance, which nurtured the local community’s affection for a special part of their urban history.”

(https://www.mercatometropolitano.com/mmarketplace/#the-mercato-story).

And this is what has been done at the former St Mark’s in Mayfair. Many of the church’s fittings (for example, the tiled floors, the stained glass, the monuments, the pulpit, and the sacred paintings at the east end of the chancel) have been preserved. Entering the church is like entering the scene of a lively gargantuan feast. Seeing the large number of customers on a weekday lunchtime demonstrates that Mercato Metropolitano have successfully created a great place to meet, eat, and drink. It is highly original and exciting, both visually and gastronomically.

In Chapter 21 (verses 12-13) of the Gospel according to Matthew, we learn that:

“…Jesus went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the money changers, and the seats of them that sold doves, And said unto them, It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves.”

I just cannot help wondering, as many of you might also be doing, what The Good Lord would have made of what can now be seen inside the Church of St Mark’s in Mayfair.

November 16, 2021

Fallen foliage

November 15, 2021

Singing and socialism in an Essex town

THAXTED IS A PICTURESQUE small town in Essex, about six and a half miles northeast of Stansted Airport. Apart from its numerous quaint old buildings, the town has three notable landmarks: an old windmill, a 15th century guildhall, and a large parish church, which was built between 1340 and 1510 during the time when Thaxted was an important centre for the manufacturing cutlery. Also, Thaxted is home to an annual music festival, whose existence derives from the discovery of the town by a composer, Gustav Holst (1874-1934), creator of “The Planets” and many other musical compositions, who was on a walking tour in Essex during the winter of 1913.

Gustav Holst in Thaxted

Gustav Holst in ThaxtedHolst, who was born in Cheltenham, was living in London by 1913 and teaching music at St Pauls School for Girls in Hammersmith, James Allen’s Girls School in Dulwich, and Morley College for adults in Lambeth. At the same time, he was busy composing.

Holst had come to study at The Royal College of Music in London in 1893. Soon after arriving in London, he became acquainted with William Morris (1834-1896) and attended meetings at the latter’s house in Hammersmith, where he would have heard lectures on socialism given by George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) and others. Holst joined the Hammersmith Socialist Society (‘HSS’), which was led by Morris. Many of the socialists he met including Shaw were vegetarians, as was the composer Wagner, whom Holst greatly admired. As a student and a regular attender of meetings of the HSS, he became a vegetarian and at the same time developed a great interest in Hinduism (www.ivu.org/people/music/holst.html). He began studying Sanskrit at The School of Oriental and African Studies (https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-music/articles/holst-and-india) and several of his compositions bear Indian-sounding titles, such as “Savitri” and another opera called “Sita”, and songs based on the Rig Veda.

According to Nalini Ghuman:

“In contrast to the vague musical orientalism in vogue during the height of the British Empire, Holst’s hymns, with their bona fide Indian texts, subjects, and musical elements, have often seemed decidedly ‘un-Indian’ to the uninformed ear: ‘Sound firm impressions of the East from a sane Western perspective’ declared The Musical Times; ‘They do not suggest a point further East than Leicester-square’ (Daily Telegraph); after all, explained the Manchester Guardian ‘many real Eastern musical ideas are frankly ugly and uninteresting’. Their Indian musical roots have long been denied by the composer’s biographers.” (https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-music/articles/holst-and-india).

However, Ghuman points out in her article that Holst did incorporate elements of Indian music, including emulating Vedic chanting and a South Indian mode, the namanarayani. You would need to be a serious musician with specialist interest in Indian music to be aware of these features whilst listening to Holst’s Indian inspired compositions.

Returning to his political leanings, major biographies of Holst tend not to focus much on his connections with socialism, but an informative article, “Gustav HoIst, William Morris and the Socialist Movement” by Andrew Heywood (Journal of the William Morris Society, vol 11, no. 4: 1996), shows that his involvement was far from inconsiderable. In addition to attending meetings of the HSS, Holst conducted its socialist choir, played the harmonium on the ‘official socialist’ cart, and was involved in the administration of the society. Heywood wrote that:

“In the light of his clear commitment to the socialist movement through 1896 it would seem likely that his involvement with the musical activity of the society did not stem from a lack of political commitment; rather it was an opportunity to serve the movement in a way which utilised his musical talents and interest.”

It was through the HSS that Gustav met his wife Isobel, who not only sang in the socialist choir but also, according to Heywood, was politically active in the society.

So, it was with a background of involvement with socialism that Holst walked into Thaxted in late 1913 and took such a great liking to the place that he rented a 17th century cottage there (actually, in Monk Street, 1 ½ miles from Thaxted) from its owner, the Jewish author Samuel Levy Bensusan (1872-1958). Thus began Holst’s several year’s association with the town. It was not long before he made the acquaintance of Thaxted’s vicar, Conrad le Despenser Roden Noel (1869-1942). After the cottage in Monk Street burnt down, Holst and his family lived in a house, The Manse (formerly known as ‘The Steps’), in the centre of Thaxted. Today, this is marked by a commemorative plaque.

Noel was not a run-of-the-mill country cleric. He was a Christian Socialist and a member of Social Democratic Federation, a founder member of the British Socialist Party, and for some time the Chairman of the Anti-Imperialist League, supporting the struggle for independence both in Ireland and India. Deeply committed to Christian socialism, social justice, and egalitarianism, Noel made sure that what went on in his parish church promoted these ideals. Noel’s biographer, Reg Groves, wrote that Conrad:

“…emphasised always that there was much more to making a new society than the acquisition of political power and the transfer of some property from the rich to the state, from one set of rulers to another. In this as in so many things, he was at one with the wisest of English socialists, William Morris, and much of what Morris said in prose and poetry and in the work of his hand, Noel tried to say in the group life he had developed at Thaxted”.

Noel and Holst shared socialist sympathies and more.

During Holst’s sojourn’s in Thaxted in between his heavy teaching and other musical commitments, he attended services led by Noel. It was after one of these held at Whitsun in 1915, that Holst, having heard the great potential of singers in the church, approached Noel and offered to give the choir the benefit of his professional skills as a trainer of vocalists. Noel, recognizing the splendid opportunity, soon had Holst become his church’s ‘master of music.’

Heywood explains that Holst’s:

“…first job was to train the choir for the church. Its members were drawn from the local population, and they achieved high standards with Holst. One member, Lily Harvey from the local sweet factory, was sent to London for professional training because of her exceptional vocal talents. In addition to his activities with the choir and playing the organ, Holst organised three major music festivals in Thaxted between 1916 and 1918.”

Lily was not the only person sent to London for musical training. The then young curate Jack Putterill, who was politically turbulent and played the organ, became one of Holst’s students at Morley College. Jack, who married Noel’s daughter, succeeded Noel as Vicar in 1942.

The festivals organised by Holst involved not only performers from Thaxted but also some of his students from Morley College and St Pauls as well as other musicians from outside the town. Each festival lasted several days, on each of which there were many hours of music making, both rehearsed concert pieces and much spontaneous music.

Holst not only helped make music in Thaxted but also composed there. The plaque on the The Manse, where he lived, is positioned on the outside of the wall of the room in which he composed. While living at Monk Street, he composed much of what was to become the well-known piece, “The Planets”. The “Jupiter” section of “The Planets” contains a tune or theme that Holst named “Thaxted” (you can listen to this familiar tune here: https://youtu.be/GdTpBSg7_8E). In 1921, “Thaxted” was used as the tune for the patriotic song “I vow to Thee, My Country”, whose words were written by the British diplomat Cecil Spring Rice (1859-1918). Holst also composed pieces specially for Thaxted and its people. These works include a special version of Byrd’s “Mass for Three Voices”, “Three Hymns for Thaxted” (later known as “Three Festival Choruses”), and a setting of the Cornish carol “Tomorrow shall be My Dancing Day” (hear it on https://youtu.be/Cz_0j__FDuc).

Although the last festival in Thaxted with which Holst was intimately involved was in 1918, he never lost touch with music making in the town, even after he moved from it to nearby Little Easton in 1925. Holst’s pupil Jack Putterill, an accomplished musician who was Thaxted’s assistant curate from 1925 to 1937 and its vicar from 1942 until 1973, helped keep the town’s musical life alive and vibrant. In the 1950s and 1960s, concerts with great orchestras such as The London Philharmonic and audiences in excess of 1000 were held in the parish church. In 1974, the hundredth anniversary of Holst’s birth, the first of what was eventually to become an annual music festival was held in Thaxted. By the 1980s, the Thaxted Festival had become a regular and respected part of the British musical calendar (www.thaxtedfestival.co.uk/).

Apart from the Festival and the house with the plaque in Thaxted, most souvenirs of Holst’s time in the town can be found within the cathedral-like parish church, which, incidentally, was once a candidate for becoming Essex’s cathedral (this honour was granted to the parish church in the centre of much larger Chelmsford). The church in Thaxted contains a photograph of Holst with singers and musicians at the Whitsuntide Festival held in 1916. Near this, there is some calligraphy with the words of “Tomorrow shall be My Dancing Day”. The church’s Lincoln organ built in 1821 by Henry Cephas Lincoln (who worked between c1810 and c1855) was played by Gustav Holst and has been recently restored. Not far from the organ is a cloth banner, sewn by Conrad Noel’s wife, which was used in the 1917 Whitsuntide Festival. It bears the words “The aim of music is the glory of God and pleasant recreation”. These words were written by the composer JS Bach (1685-1750) and were chosen for use on the banner by Holst. Near this banner, there is a bust of Holst’s friend and collaborator, Conrad Noel.

Both Holst and his student Putterill fell in love with Thaxted at first sight and were so strongly drawn to it that the town came to occupy important places in their hearts and minds. We first visited Thaxted in the early summer of 2020 soon after covid19 restrictions began to be relaxed sufficiently to permit travelling out of one’s immediate neighbourhood. Like Holst and Putterill, Thaxted made a special impression on us, so much so that we have visited it at least twice since our first encounter with it. Next year, we hope to be able to attend concert(s) at the Thaxted Festival inside a church that we have grown to love.

November 14, 2021

Washed up by the sea

November 13, 2021

A small cinematic survivor

THE COUNTY OF Essex is traversed by numerous rivers (http://essexrivershub.org.uk/), one of which is the Crouch. This lies south of the Blackwater and north of the Thames. The small town of Burnham-on-Crouch with its picturesque river front and much-favoured by yacht owners lies on the north bank of the estuary of the Crouch, about five miles from the North Sea. So near London, the town feels so far away from the metropolis – another world. Once home to several boat-building yards and various factories, Burnham appears to have become a centre for leisure activities. If you are staying in the town and have had your fill of pubs, cafés, and bistros, there is also a small cinema that shows the latest films.

The Rio cinema, despite its name, is not on the river front, but not far from it. Its decorative façade and foyer are backed by a shed like building with a corrugated iron roof, which contains the auditorium and screen, which I was not able to enter as we visited Burnham one early morning. The cinema has a long history (http://burnhamrio.co.uk/history.php), which I will summarise.

Burnham’s first cinema, The Electric, opened in 1910, making Burnham-on-Crouch one of the first towns in England to have a cinema. In 1931, this ran into problems when a rival, a purpose-built cinema, The Princess, was opened. The Electric closed and the larger Princess thrived. In the late 1960s, its name was changed to its present one, The Rio.

Burnham-on-Crouch is one of the towns and villages in the Dengie Peninsula, which until quite recently was a relatively impoverished part of Essex. During The Great Depression when money was scarce and people lived literally ‘from hand to mouth’, they had little or no money to buy cinema tickets. In those difficult times, the cinema was prepared to accept goods instead of money for tickets. The history relates:

“A Jam Jar would get you admission for the Saturday morning picture shows. Something as uncommon as an orange would admit a whole family midweek…”

Things have changed in the Dengie Peninsula. Today, many of its inhabitants and visitors are:

“… fat merchant bankers, Hooray Henrys, Minor Celebs and eastern Europe nouveau rich.”

The Rio was one of the last cinemas in England to have a gas-powered emergency lighting system. Reading this reminded me of my visits to The Everyman Cinema in Hampstead during the 1960s. I saw many films there. My enduring memory of the auditorium was that it always smelled of leaking gas. I now wonder whether The Everyman, like The Rio, also had a gas-powered backup lighting system.

The Rio in Burnham has survived two of its rivals, The Flicks in nearby South Woodham Ferrers and The Empire in Maldon, also not far away. The latter, which was housed in an Art Deco building, has sadly been demolished. The Rio’s website makes it clear that the 280 seat cinema is not in the Art Deco style. I am not quite sure which architectural style, if any, can lay claim to it. However, next time we visit Burnham, we will make sure that we watch a screening at the long-lived Rio.

November 12, 2021

Decaying but still afloat

November 11, 2021

The Connecticut connection

THE CITY OF CHELMSFORD is the county town of the English county of Essex. It is a place that until November 2021 we felt. without any reason, was not worthy of a visit and have tended to avoid, skirting it on its by-pass. It was only recently that we realised that the place is home to a cathedral. Being nearby on a recent tour in Essex and curious about its cathedral, we paid a visit to Chelmsford and were pleasantly surprised by what we found.

St Cedd window in Chelmsford Cathedral

St Cedd window in Chelmsford Cathedral The cathedral, which I will discuss later, is housed in what used to be the parish church of St Mary. The edifice is in the centre of a pleasant grassy open space. One of the buildings on the south side of this green bears a plaque commemorating Thomas Hooker (1586-1647), who was the curate and ‘Town Lecturer’ (a position established by the Puritans) of Chelmsford between 1626 and 1629.

Hooker was born in Markfield, a village in Leicestershire (www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Hooker) and studied at the University of Cambridge (https://connecticuthistory.org/thomas-hooker-connecticuts-founding-father/). At Cambridge, he underwent a moving religious experience that made him decide to become a preacher of the Puritan persuasion. He became a well-loved preacher, first serving the congregation of a church in Esher (Surrey) before moving to preach at St Mary’s in Chelmsford in 1626. A preacher in a neighbouring parish denounced Hooker to Archbishop Laud (1573-1645), a vehement opponent of Puritanism, and was ordered to leave his church and to denounce Puritanism, which he was unwilling to do. In 1630, Hooker was ordered to appear before The Court of High Commission. Soon, he forfeited the bond he had paid to the court and, fearing for his life, fled to The Netherlands.

In 1633, Hooker immigrated to The Massachusetts Bay Colony, where he became the pastor of a group of Puritans at New Towne (now Cambridge, Mass.). To escape the powerful influence of another Protestant leader, John Cotton (1585-1652), Hooker led a group of his followers, along with their cattle, goats, and pigs, to what was to become Hartford in what is now the State of Connecticut. They arrived there in 1636.

When Hooker and his followers reached the Connecticut Valley, it was still being governed by eight magistrates appointed by the Massachusetts General Court. In 1638, Hooker preached a sermon which argued that the people of Connecticut had the right to choose who governed them. This sermon led to the drawing up of a document called “The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut”, which served as the legal basis for the Connecticut Colony until 1662, when King Charles II granted The Connecticut Charter that established Connecticut’s legislative independence from Massachusetts. Hooker’s importance in this process has led him to be remembered as “the father of Connecticut.”

In 1914, the church of St Mary in Chelmsford, was elevated to the status of ‘cathedral’. The reason for this is slightly complex but is explained in a well-illustrated guidebook to the cathedral written by Tony Tuckwell, Peter Judd, and James Davy. In the mid-19th century, London expanded, and the size of its population grew enormously. Many previously rustic parishes that became urbanised were absorbed from the Diocese of Rochester into the Diocese of London. This resulted in a denudation of the Diocese of Rochester. To compensate for this, Rochester was given parishes in Hertfordshire and Essex. The Archbishop of Rochester lived in Danbury, Essex, which was closer to the majority of his ‘flock’ than anywhere in Kent. In 1877, the county of Essex was transferred into the new Diocese of St Albans in Hertfordshire. However, by 1907, 75% of the population of this new diocese were living in Essex. A further reorganisation led to the creation of two new dioceses, one in Suffolk and the other in Essex. After some acrimonious competition between the towns of Barking, Chelmsford, Colchester, Thaxted, Waltham Forest, West Ham, and Woodford, it was decided that Chelmsford should become the cathedral seat of the new Diocese of Essex. St Mary’s, where Hooker of Connecticut once preached in Chelmsford, became the new cathedral. In 1954, the cathedral’s dedication was extended to include St Mary the Virgin, St Peter, and St Cedd, whose simple Saxon chapel can be seen near Bradwell-on-Sea.

The cathedral, of whose existence we only became aware this year, is a wonderful place to see. Its spacious interior with beautiful painted ceilings contains not only items that date back several centuries but also a wealth of visually fascinating art works of religious significance created in both the 20th and 21st centuries. To list them all would be too lengthy for this short essay, so I will encourage you to visit the church to discover them yourself.

Having just visited Chelmsford, its cathedral, and its tasteful riverside developments, my irrational prejudice against entering the city and preferring to avoid it by using its bypass has been demolished. Although Chelmsford might not have the charm of cathedral cities such as Ely, Canterbury, Winchester, and Salisbury, it is worth making a detour to explore it if you happen to be travelling through East Anglia.

As a last word, it is curious that although there are places named Chelmsford in Massachusetts, Ontario, and New Brunswick, there does not appear to be one in Connecticut; at least I cannot find one.

November 10, 2021

An oversized man

MALDON IN ESSEX was home to a truly remarkable man. Edward Bright (1721-1750) was short lived but easily recognisable. In his younger days, he was a post boy riding between Maldon and Chelmsford (www.itsaboutmaldon.co.uk/edwardbright/). He had to give up this job when at the age of 12 years, his weight had reached 12 stone (www.bbc.co.uk/essex/content/articles/2008/05/15/fat_man_maldon_feature.shtml).

Later, Edward became a candle maker and grocer in Maldon. His business operated from rented premises opposite the Plume Library, a converted church in the heart of Maldon. He died at the early age of 29, which might not come as surprise when you learn that when he was 28, he weighed nearly 42 stones (265 kilogrammes). A year later, he had put on another two stones. By that time, he was 5 foot and 9 inches in height, his chest measurement was 5 foot and 6 inches, and his stomach measured 6 feet and 11 inches (about 210 centimetres). These measurements necessitated special clothing to be made to fit him.

On the first of December 1751, a bet was made at Maldon’s King’s Head Inn. A prize of a ham, some chickens, and several gallons of wine, was to be awarded if nine men were able to fit inside Bright’s enormous waistcoat. The nine men, whose names and professions are listed on a memorial in Maldon, were easily accommodated inside the vast waistcoat. The memorial, located in an alleyway that connects the High Street with a car park, has a depiction of this occasion, a bas-relief sculpted in bronze by Catharni Stern (1925-2015) in 2000.

Bright fathered at least one child, also named Edward Bright. The parish burial register records that when the overweight man was buried at All Saints’ Church:

“’A way was cut through the wall and staircase to let it down into the shop; it was drawn upon a carriage to the church and slid upon rollers to the vault made of brickwork, and interred by the help of a triangle and pulley. He was a very honest tradesman, a facetious companion, comely in his person, affable in his temper, a tender father and valuable friend.” (www.itsaboutmaldon.co.uk/edwardbright/)

Although there was much of Edward Bright to be seen when this larger than average character lived in Maldon, this pleasant town has much more to offer the visitor including a lovely promenade alongside the estuary of the River Blackwater.

November 9, 2021

A flourishing pub in Hampstead

ONCE LONDON’S HAMPSTEAD had two pubs or taverns named ‘The Flask’. This should not come as a great surprise as Flask used to be a common name given to pubs. One of them, The Upper Flask, used to be located at the top (northern) end of East Heath Road and the other, The Lower Flask’ was (and still is) on Flask Walk, a street leading off Hampstead High Street.

The Upper Flask used to be a remarkable establishment. Once called ‘The Upper Bowling Green House’ because of its good bowling green, it was a meeting place favoured by fashionable and ‘cultured’ men (mainly) and women during the 18th century. It was a summer meeting place for The Kit Kat Club, which thrived in the early 18th century and whose members included literary figures and political personalities, who supported the Whig Party. The Upper Flask figures several times in “Clarissa”, a lengthy novel by Samuel Richardson (1689-1761), first published in 1747. The place ceased operating as a hospitality business in the 1750s, when it became a private residence (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/v...). In 1921, it was demolished to clear the site for building the Queen Mary Maternity Hospital (https://ezitis.myzen.co.uk/queenmaryhampstead.html), which has since become the site of a luxury housing complex.

The Lower Flask (in Flask Walk) is also mentioned in “Clarissa”, but unflatteringly as:

“… a place where second-rate persons are to be found often in a swinish condition,” (quoted from “Old and New London”, by Edward Walford, about 1880).

Unlike the lost Upper Flask, the formerly named Lower Flask is still in business, but much has changed since Richardson published his novel.

Located at the eastern end of the pedestrianised stretch of Flask Walk, the former Lower Flask, renamed The Flask, was rebuilt in 1874 (and extended in 1990; https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1322190). Formerly, it had been a thatched building and was a place where mineral water from Hampstead’s chalybeate springs was sold. It and Keith Fawkes’ second-hand bookshop are the only things in Flask Walk, which were in existence when I used to visit Hampstead regularly in the 1960s and 1970s. In those, now far-off, days, I remember that there used to be another second-hand bookshop and a butcher, both on the south side of the passageway. Before the 20th century, there used to be a fair held for a few days in August on the triangular open space a few yards downhill from The Flask pub. Close to The Flask, also on Flask Walk, miscreants could be found languishing in the parish stocks. Both the stocks and the fair are now but long distant memories recorded only in books published many decades ago.

Oddly, despite visiting Hampstead literally thousands of times during the last more than 65 years, it was only on Halloween 2021 that I first set foot in the Flask pub, and I am pleased that I did. The front rooms of the pub retain much of their Victorian charm and the rear rooms are spacious. Although we only stopped for a drink, I could see that the Sunday lunches being served to customers around us looked delicious. We hope to return there soon.

November 8, 2021

A sculpture, a steeple, and stucco

LANCASTER GATE IS ten minutes’ walk or a three-minute bus ride away from where I have lived for over 29 years. I have passed it innumerable times, yet I have never explored it. Yesterday, the 30th of October 2021, I decided it was high time that I took a closer look at the place. The name refers to an entrance to Kensington Gardens as well as a nearby network of streets. The network includes a long street extending from east to west between Craven Terrace (near Paddington Station) and Leinster Terrace. The section of road between Craven Terrace and Bayswater Road is also called Lancaster Gate. Midway along the long east-west section of the Gate, there is a wide street, almost a square or piazza, that leads to Bayswater Road. This rectangular piazza is south of a rectangular loop to the north of the east-west section, in the centre of which there is a 20th century building called Spire House. If this sounds confusing, then please look at a map!

What I have called the ‘piazza’ opens out onto Bayswater Road. In the middle of it, there is a monument topped with the weather worn sculpture of a seated child, probably male. The sculpture sits above a bas-relief depicting the western façade and the dome of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral. Below, on the south side of the pedestal, there is a bas-relief, depicting the face of a man with a bushy moustache and a long luxuriant beard. Weather and/or pollution has worn away details from his portrait. At first sight, I thought that it was a representation of George Bernard Shaw as an old man, but it is not. It is, according to the almost undecipherable inscription beneath it, the face of Reginald Brabazon, the 12th Earl of Meath, who lived from 1841 to 1929. The words on the plinth include that he was “a patriot and a philanthropist”.

Brabazon was Anglo-Irish and born in London (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reginald_Brabazon,_12th_Earl_of_Meath). Educated at Eton, he became a diplomat, but resigned from the Diplomatic Service in 1877. Ten years later, he joined the House of Lords as a Conservative peer. Reginald and his wife, Mary, devoted much of their lives to relieving human suffering and ameliorating social conditions. Amongst his many good works was the establishment (in 1882) of a charity called the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association, whose aim was the preservation of public open spaces and the creation of new ones, which might explain why the memorial to him faces Hyde Park. The Portland stone monument, known as The Meath Memorial, was designed by Joseph Hermon Cawthra (1886-1971) and unveiled in 1934.

A few feet north of Brabazon’s memorial, which stands on a wide traffic island, there is a slender stone column topped by an ornate octagonal structure surmounted by a shiny metal crucifix. The base of this column reveals that it is was built as a WW1 memorial. In the pavement between the two memorials, the City of Westminster has set several informative panels about the history of Lancaster Gate. The development of Lancaster Gate, originally known as ‘Upper Hyde Park Gardens’, began in the late 1860s, an initiative of the developer Henry de Bruno Austin. Many of the houses he built have rich stucco facades and porches supported by neo-classical style pillars. Quite a few of them are now hotels. These buildings are interspersed with a few newer buildings, presumably where the originals were bombed during WW2. However, most Lancaster Gate’s houses are those built in the 19th century.

The name Lancaster Gate was chosen to honour Queen Victoria, who was amongst many other things, the Duchess of Lancaster.

Before Lancaster Gate was developed, it was mostly agricultural land. Until 1775, the composer, actor, botanist, and playwright John Hill (1716-1775) had his Physic Garden here. By 1795, visitors flocked to the area to enjoy the springs and fresh air at the Bayswater Tea Gardens, which later was renamed the Flora Tea Gardens, and then the Victoria Tea Gardens. This establishment closed in 1854.

At the southern end of the loop and towering above the plaza with its two monuments, there is a tall church tower with a spire. This is all that remains of the Christ Church, Lancaster Gate, whose construction began in 1854. The last service to be held in the church was in 1977, by which time the roof was badly infected with dry rot. The church was demolished, but the tower retained. Where the body of church stood, there is now a block of flats. Opened in about 1983, it is appropriately named Spire House. Its 20th century architecture is quite attractive and contrasts dramatically with the stuccoed Victorian buildings that face its west, north, and east sides. Spire House has external concrete supporting pillars that suggest an updated version of the flying buttresses used in mediaeval church architecture.

Lancaster Gate is a relatively unspoilt example of mid-Victorian town planning and worthy of a short visit. While walking around the area, I only spotted one blue plaque, commemorating a resident worthy of note. It recorded that the “Chemical Scientist” Sir Edward Frankland (1825-1899) lived in Lancaster Gate from 1870 to 1880. He was one of the founders of organo-metallic chemistry and a discoverer of Helium. Also, he took an active interest in the problem of pollution of rivers and the quality of London’s water. I trust that he would be pleased to know that fish have returned to London’s once filthy River Thames.

After exploring Lancaster Gate and its sea of stuccoed facades, head east into Craven Street, where you can find several cafés and at least one pub.