Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 142

December 7, 2021

The first of its kind in England

THE ARCHITECT JOHN Soane (1753-1837) was skilled in designing buildings with features to permit natural light to reach parts of them that were far away from their exteriors. Good examples of this were the two homes he designed for himself, one in Lincolns Inn Fields, now the Soane Museum, and the other in Ealing, the recently restored Pitzhanger Manor. Another superb example, which we visited recently (December 2021) is the Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London. Completed and opened in 1817, it became the first picture gallery in England that was open to the public.

Light enters Soane’s galleries at Dulwich from above via overhead sky lights. These were placed in such a way that they illuminate the hanging spaces without allowing direct sunlight to hit the paintings on the walls. This system has since been adopted in many other art galleries. Newer rooms, lit entirely by artificial lighting, are used for temporary exhibitions including that of the woodcuts of the American artist Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), which we saw on our latest visit. Compared with Soane’s galleries, these newer ones are far less impressive, and despite the modern lighting they feel claustrophobic and rather gloomy.

The permanent collection of old masters, which is hung in Soane’s original galleries, is fabulous. Some of the paintings were parts of collections made before the 19th century. Others were supplied by the artist Sir Francis Bourgeois (1753–1811) and his business partner, the art dealer and collector, Noël Desenfans (1744–1807). Together they ran an art dealership in London and were commissioned in 1790 to purchase a collection of paintings for the then King of the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania, Stanisław August Poniatowski (1732-1798). It took them five years to do this but by 1795, the Commonwealth had been dissolved. The collection remained in England. After Desenfans died, Bourgeois inherited the collection and then commissioned Soane to design a gallery to house it. The superb gallery at Dulwich came into existence. Soane included within it a small circular mausoleum in which the remains of both Desenfans and Bourgeois have been placed. Rather irreverently, I felt, it was being used to screen a video about the artist Helen Frankenthaler.

In 1944, during WW2, the western façade of Soane’s gallery was badly damaged by bombing (a German V1 flying bomb) but it has been well-restored. Later, in 1999, a new café and other facilities in a modern style were built to the designs of the architect Rick Mather (1937-2013).

As for the exhibition of works by Frankenthaler, this was a delightful surprise. It is a collection of colourful abstract woodcuts that are the result of years of the artist’s complex and imaginative experimentation. Many of the works reminded me of, but were not identical to, the subtleties of Japanese ceramic glazes. Despite being displayed in galleries far less satisfactory than those designed by Soane, this as an art show well worth visiting before it ends on the 18th of April 2022.

December 6, 2021

Shadow

December 5, 2021

A perfect pub

IT MIGHT BE OBVIOUS to many that the village pub is, along with the local parish church, often the social hub of small settlements all over England. Since the outbreak of the covid19 pandemic, we have not made our usual annual long trip to India. Instead, when public health regulations have permitted, we have been taking the opportunity better our knowledge of the country where we live, England, by making frequent trips to different parts of the land. On all these excursions, we have stopped for food and drink at pubs in many small places. Some of these pubs have become more like restaurants than traditional village social centres, but many still act as communal living rooms where local people gather to drink and chat together.

Inside the Pig and Abbot

Inside the Pig and AbbotIn Cavendish, a small village in Suffolk, there are two pubs. One is more of a restaurant than a traditional pub. By the way, it serves very excellent food. The other pub serves no food except packets of potato crisps. When we visited it, we were told that it only offers drinks. This pub was full of locals talking to each other quite animatedly. One, whom we overheard, claimed to be having a fantastic sexual relationship with a French lesbian, in whose house he had done some plumbing work.

One pub, which we have visited more than half a dozen times since early 2020, is in south Cambridgeshire. The Pig and Abbot at Abingdon Piggots, a village with about 60 households not far from Royston, successfully combines being a meeting place for locals with being a place where very well prepared, tasty food may be enjoyed, either in a small restaurant area or at tables near the centrally located bar.

The current owners, Mick and Pat, have owned the pub for almost 20 years. Pat is a superb cook and warm hostess, and Mick is a knowledgeable and charming host. He told us that the early 18th century building in which his pub is located used to be the local dower house, in which the wife of the lord of the manor lived after she was widowed. Back in those days, women usually outlived their husbands. The dower house was far from being a peaceful retirement home for widows of lords of the manor. It was a hive of activity. It was in the dower house at Abingdon Piggots that bread was baked, and other food prepared, not only for the manor house, but also for all the local families that worked for the lord of the manor. The manor, which had been in the Piggott family, many of whom have memorials in the local church, ended up in the hands of the De Courcy-Ireland family. In the early 20th century, a descendant of the Piggott family, who had inherited the manor married the Reverend Magens De Courcy-Ireland (died 1955). Mick told us that the dower house became a pub during the second half of the 19th century.

While we were enjoying a superb lunch during a recent visit to the Pig and Abbot, we asked Nick how many of the local villagers used the pub regularly. He told us that of the 60 households, 10 were regulars. We wondered whether we were amongst his customers who lived furthest away from the village. He said that we are, but his furthest customer, a former resident in the village, a biologist, now lives in Fairbanks, Alaska. However, whenever he is in England, he makes a point of visiting the Pig and Abbot. Despite this outlier and us, most of the regulars do not come from afar, and I noticed that Nick seems to know most of his customers by their first names.

Of the many pubs that we have visited during our extensive roaming around the English countryside, the Pig and Abbot has become our favourite. From its warm welcoming staff, to its great food and drink, to its range of well-chosen decorations, and to its lovely wood burning fireplaces, it ticks all the boxes, making it a perfect pub. Visiting the Pig and Abbot gives one a wonderful idea of what has made the English country pub such a successful institution over many centuries.

December 4, 2021

A lady in Hampstead and Boy George

GROVE PLACE IS a short street running southwest from Hampstead’s steeply inclined Christchurch Hill. We often walk along it on our way to the lovely café at nearby Burgh House. A building containing numbers 29-31 Grove Place has often attracted my attention because its roof is topped with a couple of cupolas, each supported by four carved wooden pillars. These stand on either side of a grand central façade. The edifice bears a plaque, which is in an excellent state of preservation, that reads:

“This stone was laid by Mrs Sarah A Gotto on the 13th of July 1886 being the 50th Yr of the reign of her majesty Queen Victoria”

Elsewhere on the wall facing Grove Place there is a metal shield, painted black, which bears the following:

“1871. SPPM”

I was a bit puzzled by this because 1871 was some years before the stone was laid by Mrs Gotto.

I was pleased to discover that this building has been described in a book I possess, “The Streets of Hampstead” by Christopher Wade. He revealed that it was converted in 1970 from Bickersteth Hall, a hall built for the nearby Christ Church in 1895, and named after a former vicar, who later became the Bishop of Exeter. This gentleman was Edward Bickersteth (1825-1906), who had been vicar of Christ Church in Hampstead from 1855 to 1885 (www.praise.org.uk/hymnauthor/bickerst...). Wade adds that it is confusing that the 1871 St Pancras shield and the 1886 Mrs Gotto plaque have been placed on the building. So, it seems that Mrs Gotto might have had little to do with laying the first brick of the building, but I wondered who she was.

Wade describes Sarah Gotto as Mrs Edward Gotto. Edward was most probably Edward Gotto (1822-1897), a civil engineer and architect who entered a partnership with Frederick Beesley in 1860 to create the engineering firm of Gotto and Beesley, which flourished for 30 years and carried out drainage works in towns all over the world including Rio de Janeiro, Seaford, Trowbridge, Evesham, Huyton and Roby, Redditch, Brentford and Cheshunt; and the drainage and water-supply of Campos (Brazil), Oswestry, Leominster and Cinderford (www.gracesguide.co.uk/Edward_Gotto). According to his obituary, Mr Gotto lived in Hampstead in a house called The Logs on East Heath Road. Built in 1868, The Logs, was as I have described elsewhere (see https://adam-yamey-writes.com/2021/02/01/finding-boy-george-and-bliss-in-north-london/), much later home to the comedian Marty Feldman and the singer Boy George. Edward’s wife Sarah was born Sarah Ann Porter (1829-1901; https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/L1Q6-7NL/major-harold-ralph-gotto-1868-1957), She and Edward had eight children, one of whom was Harold Ralph Gotto. He was born in 1868 in Hampstead and later became a major in the British Army.

All of this is interesting enough, but none of it explains (to me) why Sarah is commemorated by the plaque on the house in Grove Place. If anyone knows the reason, I would be pleased to hear from them.

December 3, 2021

Swans on the Serpentine

December 2, 2021

A pottery and a prison

HAMPSTEAD IN NORTH London is full of interesting nooks and crannies.

At the west end of Well Walk in Hampstead, near the lower end of Flask Walk, there is a corner building with a Georgian shop front. It is now a small theatre but was once the Well Walk Pottery, which occupied this place for many years. The pottery was started by the potter Christopher Magarshack in 1959. According to Bohm and Norrie, writing in their “Hampstead: London Hill Town”, published in 1980, Elsie, the widow of the Russian Jewish translator and writer David Magarshack (1899-1977), lived there. She bought this corner building, which had formerly been Sidney Spall’s grocery shop in 1957, for Christopher to use as his pottery. His father, David, left his birthplace Riga, then in Russia in 1918 and later lived above the shop. Elsie died in 1999, aged 100. In addition to selling pottery there, the pottery also held classes for ceramicists, some of whom now have good reputations. David’s daughter Stella, a fine artist, was the Head Art Teacher at King Alfred’s, a ‘progressive’ school situated between Hampstead and Golders Green. In 2016, aged 87, she was brutally attacked in the street close to her home. Now, the premises is to be home to a theatrical enterprise, The Wells Theatre. Its present owners have decorated one of its windows has been decorated with a pictorial history of the premises.

Before returning uphill along Flask Walk towards the pub, you will pass a pair of doors covered in metal studs arranged neatly in geometric patterns. According to an article in the January 2018 issue of “Heath and Hampstead Society Newsletter”, this pair of studded doors:

“…is supposed to have come from Newgate Prison,”

The prison closed in 1902.

December 1, 2021

Two freedom fighters in London’s Hampstead

PLATTS LANE WINDS its way between London’s Finchley Road and West Heath Road in Hampstead. It follows the route of a track between Hampstead Heath and West End (now West Hampstead). This track was already in existence by the mid-18th century. According to a historian of Hampstead, Christopher Wade, the thoroughfare was first called Duval’s Lane to commemorate a 17th century French highwayman. Louis (alias Lodewick alias Claude) Duval (alias Brown) who was, according to another historian, Thomas Barratt, famed for being gallant towards his victims, many of whom he robbed on Hampstead Heath. Barratt related:

“It used to be told that, after stopping a coach and robbing the passengers at the point of the pistol on the top of the Hill, he would, having bound the gentlemen of the party, invite the ladies to a minuet on the greensward in the moonlight.”

Duval was hung at Tyburn soon after 1669.

Over time this track’s name became corrupted to Devil’s Lane. A pious local resident, Thomas Pell Platt (1798-1852), probably put an end to that name after he had built his home, Childs Hill House, nearby in about 1840.

Platt graduated at Trinity College in Cambridge in 1820 and became a Major Fellow of his college in 1823. While at Cambridge, he became associated with the British and Foreign Bible Society and was its librarian for a few years. He was also an early member of The Royal Asiatic Society (founded 1823) as well as a member of The Society of Antiquaries of London. In 1823, he prepared a catalogue of the Ethiopian manuscripts in a library in Paris. In addition, he did much work with biblical manuscripts written in the Amharic and Syriac languages. Apart from being a scholar, he was an intensely religious man. He died not in Hampstead but in Dulwich.

Platt lived near the lane named after him for quite a few years. The same cannot be said for a later resident of Platts Lane, Tomas Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937), who was born in Moravia (now a part of the Czech Republic). Masaryk added the name Garrigue to his own when he married the American born Charlotte Garrigue (1850-1923) in 1878. A politician serving in the Young Czech Party between 1891 and 1893, he founded the Czech Realist Party in 1900. At the outbreak of WW1, he decided that it would best if the Czechs and Slovaks campaigned for independence from the Austro-Hungarian empire. He went into exile in December 1914, staying in various places before settling in London, where he became one of the first staff members of London University’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies, then later a professor of Slavic Research at Kings College London.

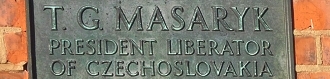

In London, Masaryk first lived in a boarding house at number 4 Holford Road in Hampstead (http://tg-masaryk.cz/mapa/index.jsp?id=285&misto=Pobyt-T.-G.-Masaryka-1915-1916). In June 1916, he moved from there to number 21 Platts Lane, which was near to the former Westfield College where his daughter Olga was studying. The house, the whole of which he rented, became a meeting place for the Czechoslovak resistance movement in England. Masaryk stayed in Platts Lane until he departed for Russia in May 1917. It is possible that he returned there briefly when he made a visit to London in late 1918. On the 14th of September 1950, the Czechoslovak community affixed a metal plaque to the three-storey brick house on Platts Lane, which was built in the late 1880s. It reads:

“Here lived and worked during 1914-1918 war TG Masaryk president liberator of Czechoslovakia. Erected by Czechoslovak colony 14.9.1950”

Actually, Masaryk only used the house between 1916 and 1917. The year that the plaque was placed was a century after Masaryk’s birth year. The day chosen, the 14th of September, was that on which he died in 1937.

Not too far away from Masaryk’s Hampstead home, there is a place on West End Lane that used to be called The Czechoslovak Club before it became the Czechoslovak Restaurant and currently Bohemia House. Here you can see a portrait of Masaryk and enjoy yourself sampling Czech beers and food. The establishment is within the Czechoslovak National House, which was founded as a club in 1946.

The houses where Czechoslovakia’s freedom fighter lived in London still stand in Hampstead. However, that is no longer the case for another freedom fighter and founder of a new nation, who lived near Platts lane on West Heath Road, the wealthy barrister and founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948). In the 1930s, Jinnah practised law in London. One of his biographers, Hector Bolitho (1897-1975) wrote (in 1954):

“One day in June 1931, when Jinnah was walking in Hampstead, he paused before West Heath House, in West Heath Road. It was a three-storied villa, built in the confused style of the 1880s, with many rooms and gables, and a tall tower which gave a splendid view over the surrounding country. There was a lodge, a drive, and eight acres of garden and pasture, leading down to Childs Hill.

All are gone now, and twelve smaller, modern houses occupy the once-pretty Victorian pleasance. Nearby lives Lady Graham Wood, from whom Jinnah bought the house; and she remembers him, on the day when he first called, as “most charming, a great gentleman, most courteous…

… In September 1931 Jinnah took possession of West Heath House, and he assumed the pattérn of life that suited him. In place of Bombay, with the angers of his inheritance for ever pressing upon him, he was able to enjoy the precise, ordained habits of a London house. He breakfasted punctually and, at nine o’clock, Bradbury was at the door with the car, to drive him to his chambers in King’s Bench Walk. There he built up his new career, with less fire of words, and calmer address, than during the early days in Bombay.”

It was at West Heath House that Jinnah entertained Liaquat Ali Khan (1895-1951), another of Pakistan’s founding fathers and its first Prime Minister, who had arrived from India. Bolitho wrote:

“A great part of the fortunes of Pakistan were decided оn the day, in July 1933, when Liaquat Ali Khan crossed Hampstead Heath, to talk to his exiled leader.”

Bolitho recorded that Liaquat’s wife recalled the occasion:

“Jinnah suddenly said, ‘Well, come to dinner on Friday.’ Sо we drove to Hampstead. Іt was a lovely evening. And his big house, with trees—apple trees, I seem to remember. And Miss Jinnah, attending to all his comforts. I felt that nothing could move him out of that security. After dinner, Liaquat repeated his plea, that the Muslims wanted Jinnah and needed him.”

At the end of the evening, Jinnah said to Liaquat:

“’You go back and survey the situation; test the feelings of all parts of the country. I trust your judgment. If you say “Come back,” I’ll give up my life here and return.’”

Jinnah returned to India in 1934, and Pakistan was created in August 1947.

Judging by Bolitho’s description, Jinnah’s Hampstead house could not have been very far from the house which Masaryk rented in Platts Lane, which, like Jinnah’s garden, is close to, or more accurately on, Childs Hill. I have found Jinnah’s house marked on a map surveyed in the 1890s. It was located on the west side of the northern part of West Heath Road, about 430 yards north of Masaryk’s residence on Platts Lane.

It might come as much of a surprise as it was to me to learn that the founders of two countries, each of which was founded soon after the ending of World Wars, both lived in Hampstead for brief periods in their lives.

November 30, 2021

Black abolitionists in Westminster

WESTMINSTER ABBEY IS costly for tourists to enter. Currently (November 2021) the entrance ticket ranges in price from £10 for a child to £24 for a full-price adult ticket. Without doubt, the Abbey is well worth a visit, but if you do not feel like spending so much money, its neighbour, the St Margaret’s Church is also full of interest but charges no entry fee.

Because the present Abbey was once the church attached to a monastery, St Margaret’s was built in the 11th and 12th centuries to provide a place of worship for the (non-ecclesiastical) residents of Westminster. When the residential population of the area declined, it became what it is now, the parish church for The House of Commons. The first church on the site was built in the Romanesque style, but when this deteriorated in the 14th century, it was replaced by the present structure built in the Perpendicular (gothic) style. Since then, like many old churches it has undergone various modifications over the centuries.

Amongst the many fascinating things within the church, which are described in an excellent booklet by Tony Willoughby and James Wilkinson, several things particularly attracted my attention. First of all, several of the windows in the south wall of the church contain superb modern stained glass designed by the painter John Piper (1903-1992) and created by Patrick Reyntiens (1925-2021). The were installed in 1966 to replace Victorian windows that were destroyed during WW2. Piper’s windows alone are a good reason to visit the church.

Another thing that caught my eye is a pair of doors on the north side of the church. These are covered with red leather, each one embossed in gold with a portcullis, surmounted by a crown, the symbol of Parliament. Some of the prayer kneelers are also decorated with this symbol.

Amongst the many tombs and funerary memorials within the church, there is one to the artist Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677). Born in Prague, he left the city when the Emperor Ferdinand the Second ordered Bohemian nobility to convert to Roman Catholicism or leave the country. A highly prolific and much-admired artist, creator of many works including detailed views of London, he died a poor man in Westminster. His monument is on the north wall.

Amongst the many memorials on the south wall there is an oval plaque commemorating the fact that in 1759, Olaudo Equiano (aka Gustavus Vassa) was baptised in the church when he was a slave owned by a sea captain, Michael Henry Pascal. Equiano (c1745-1797) was a black African slave, who gained (purchased) his freedom in 1766. After numerous adventures, which he related in his autobiographical work “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano”, published in 1789 in London, he became active in the nascent movement to abolish the slave trade. In addition to his book, he wrote a great number of pamphlets and letters to the press.

Whereas I was able to spot the plaque for Equiano with no difficulty, I was unable to see the grave of another abolitionist, also a former slave, Ignatius Sancho (c1729-1780), who was born on a slave ship and is buried in the churchyard of St Margaret. He married a West Indian woman, Anne Osborne, in St Margaret’s, ran a grocery shop in Westminster, acted, composed music, and wrote against slavery using the pseudonym “Africanus”. He was the first black Briton to vote in a parliamentary election. He cast his vote both in 1774 and 1780.

In addition to these two black abolitionists, the church contains memorials to two men who tried to alleviate the suffering of slaves in the Americas, Richard Burn (c1744-1822) and Thomas Southerne (1660-1746). The latter was one of the first writers in English to denounce slavery.

I hope that what I have written above will help to distract you from the idea of visiting only Westminster Abbey and to encourage you to make plenty of time to explore St Margaret’s.

November 29, 2021

On the wagon – no longer!

IN THE CENTRE of Warwick, there is a building with superb examples of Victorian decorative terracotta work. High on its façade, in terracotta lettering are the words “coffee” and “tavern” because this edifice began its life as a coffee house back in 1880.

Designed by a Warwick architect Frederick Holyoake Moore (1848-1924), it was constructed for a local manufacturer and philanthropist Thomas Bellamy Dale (1808-1890). He was mayor of Warwick three times and:

“…was a philanthropist in every sense of the word, for his name was connected with the principal benevolent institutions of England, of which he was a generous supporter; as a public man he took a very active part in the sanitary improvements of the borough of Warwick, and in the adoption of the Free Library Act. He was a generous supporter of every useful institution in the town, and, though exceedingly charitable, was most unostentatious in all his benefactions.” (www.mirrormist.com/t_b_dale.htm)

In the 19th century, alcohol consumption was considered to be responsible for the ill-health of poor people and detrimental to their general well-being. Dale built his coffee tavern and hotel to offer an alternative to alcohol and pubs. His establishment had:

“…a bar and coffee room on the ground floor with service rooms at the rear; a bagatelle room, smoke room and committee and club room on the first floor, and rooms for hotel guests on the second floor.” (www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/article/coffee-tavern-warwick).

The place was designed to keep people away from alcohol, “on the wagon”.

Now, all has changed. Today, the building still offers refreshments and hotel rooms, but does something that the late Mr Dale, who encouraged people to become teetotal, would not approve. Customers at what is now named “The Old Coffee Tavern” can now enjoy not only coffee but also a full range of alcoholic drinks. He might be pleased if he knew that when we visited its pleasant lounge decorated with colourful tiled panels, we chose to sip coffee rather than drinks containing an ingredient that did not meet with his approval.