Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 138

January 16, 2022

Mushroom man

January 15, 2022

Fish on the roof

WEATHERVANES ATTRACT BOTH wind and my attention. The variety of forms that these wind direction indicators assume is why I enjoy looking at them. A few days ago, whilst crossing London Bridge I spotted a building with two weathervanes on its roof. They are shaped like fish. But they are not alone because the roof is decorated with more metal fish. Their presence is appropriate because between 1875 and 1982, this arcaded edifice next to the river was home to the Billingsgate fish market. Today, the place is used as a venue for gatherings of various sorts.

Writing in 1598, John Stow (c1524-1605) noted that the ward of Billingsgate was named after ‘Belinsgate’. It was then, he wrote:

“… a large water-gate, port, or harborough, for ships and boats, commonly arriving there with fish, both fresh and salt, shell-fishes, salt, oranges, onions, and other fruits and roots, wheat, rye, and grain of divers sorts, for service of the city and parts of this realm adjoining.”

He also mentions that in the reign of Edward III (reigned 1327-1377), Belinsgate was then a much-used place for mooring ships and that these all attracted harbour fees, which depended on their size.

John Timbs (1801-1875), writing in his “Curiosities of London”, published in 1867 provided more of the history of Billingsgate. He wrote that it had been a landing place, if not also a marketplace, since the reign of King Ethelred II (reigned 978-1013). In 1699, an Act of King William III declared that Billingsgate was a market for all kinds of fish, and that it should be close to London Bridge. Timbs recorded:

“The Market, for many years, consisted of a collection of wooden pent-houses, rude sheds, and benches: it commenced at three o’clock AM in summer and five in the winter: in the latter season it was a strange scene, its large flaring oil lamps showing a crowd struggling amidst a Babel din of vulgar tongues, such as rendered “Billingsgate” a byword for low abuse … In Baileys “Dictionary” we have; a Billingsgate, a scolding, impudent slut’”

In 1849, the market was enlarged, making it more spacious and less of a scrum that it had been previously. In 1850, the first Billingsgate market building was ready for use but by 1873, when it was demolished, it was already too small for its purpose. The former market building, which we see today with its rooftop fish ornaments, was designed by the City Architect Horace Jones (1819-1887) and opened for use in 1876. Jones’s most famous building, Tower Bridge, was completed after his death.

After it ceased being used as a fish market, instead of being demolished, the old Billingsgate market was:

“Given an industrial twist by architect Lord Richard Rogers, the building has undergone an amazing transformation, from the 19th century’s largest fish market to London’s premier event space.”

Thanks to that repurposing, we can still enjoy sight of fish on a roof in the heart of the City of London.

January 14, 2022

Pictures at an exhibition

Overlooked by The Shard,the White Cube Gallery in Bermondsey Street, near to London Bridge Station, provides wonderful expanses of well-lit exhibition space. One can explore works of contemporary art in an uncluttered, airy environment. This is so much better than many traditional exhibition spaces such as in 19th century galleries, or even in the relatively recently constructed Tate Modern. Visiting the White Cube in Bermondsey is a worthwhile experience not only because of its wonderful spaciousness but also because it often displays exciting works of art. And when you have had your fill of art, there are plenty of places in Bermondsey Street where you can find a wide variety of food and drink.

Here is some information about the building from https://www.dezeen.com/2011/10/14/white-cube-bermondsey-by-casper-mueller-kneer/:

“144–152 Bermondsey Street is an existing warehouse and office building, set back from Bermondsey Street via an entrance yard. The building dates from the 1970s and has a modernist industrial appearance, with long horizontal window bands and a simple cubic shape. The outer walls of the building are constructed from dark brown engineering brick, with a concrete and steel framed internal structure…

…The new gallery spaces were inserted as self-supporting freestanding volumes, barely touching the envelope of the existing building.The powerfloated concrete floors can take loadings up to 100 KN/m2. Walls and ceilings are constructed as steel cages allowing art to be installed at almost any point within the space. Structural exclusion zones allow the punching through of walls at selected locations to allow entry points into the exhibition spaces to be coordinated with the ever-changing displays.”

January 13, 2022

Cormorant

January 12, 2022

Me Here Now

UNTIL RECENTLY, LONDON Bridge railway station, overshadowed by the glass-clad Shard skyscraper, was not visually appealing. It was a place that you lingered no longer than necessary either whilst waiting for a train or having just disembarked.

Today, the station has been transformed into a place where you might want to linger and explore. It has been cleaned up and tastefully remodelled. The station and the tracks leading from it have always been above ground, supported by innumerable brickwork arches. A few years ago before the improvement works were carried out, many of these archways led to passages beneath the station, most of them dark and unwelcoming.

One of these was the Stainer Street Walkway that links St Thomas Street and Tooley Street and passes through the station’s foyer from which stairways lead up to platforms. This wide passageway lined with ochre coloured brickwork is now well-lit and apart from being a bit chilly, quite pleasant. But look up, and you will see three enormous, reflective, decorative umbrellas suspended from the ceiling. Each umbrella is decorated with geometric symbols and lettering. The lettering forms sets of words that are supposed to be meaningful for those who bother to read them.

Together, these umbrellas comprise an artwork, “.Me. Here. Now” by Mark Titchner , which were put in place in mid-2019. With the decrease in passenger numbers since the start of the covid19 pandemic, this lovely set of artefacts have been seen by far fewer people than were anticipated by the commissioners of this creation, Network Rail.

January 11, 2022

Sir Anthony Blunt sat here often

HOME HOUSE IN London’s Portman Square was completed in 1777 for the wealthy Elizabeth Home, Countess of Home (c1703-1784). Born in Jamaica into a slave-owning family, her wealth was produced by the unpaid labour of slaves imported from Africa. The house is remarkable, especially for its intricately detailed interior décor designed by the architect Robert Adam (1728-1792).

In 1933, Home House became home to the Courtauld Institute of Art, now part of the University of London. A close friend of mine, now sadly deceased, studied at the Courtauld for both his bachelor’s degree and his doctorate. Whilst writing his doctoral thesis, my friend was supervised by Sir Anthony Blunt (1907-1983). Blunt was the director of the Courtauld from 1947 to 1974. He was also in charge of the Royal Collections of art from 1945 onwards. In addition, he carried out much important scholarly work in the field of history of art. Blunt, as director of the Courtauld, was given a flat in Home House.

Until 1979, few people knew, or even suspected, that Blunt had been involved with spying for the Soviet Union. When this came out into the public domain, Blunt’s downfall commenced. He was stripped of his knighthood and his Honorary Fellowship at Cambridge’s Trinity College was rescinded. Also, Blunt resigned as a Fellow of the British Academy. Soon after his exposure as an espionage agent, who worked against his own country for the Soviet Union, Blunt ceased residing at Home House. In 1989, the Courtauld Institute shifted from Home House to larger premises in Somerset House in the Strand. Home House remained vacant until 1998, by which time it had been beautifully restored and adapted to become a private social club. During a recent visit to Home House when we were entertained by a friend, our host, a member, took us to see an interesting exhibit, which is housed in the wash basin area of one of the Club’s unisex toilets. We were shown a glass-fronted display case containing a wooden furniture item. It bears a label with the words: “From the bathroom of Sir Anthony Blunt”. The labelled object is the toilet seat on which Blunt must have sat numerous times, and its wooden lid. Another case in the room contains Blunt’s telephone. Although the loo seat and the ‘phone are unremarkable except for their provenance, the rest of Home House is a visual delight.

January 10, 2022

mutANTS

January 9, 2022

A brave man

FIREFIGHTING IS NEVER without hazard. This is something that James Braidwood (1800-1861) knew only too well when he attended a fire in Tooley Street near London Bridge station on the 22nd of June 1861.

Braidwood was born in Edinburgh, Scotland and in 1824, he was appointed Master of Fire Engines just before The Great Fire of Edinburgh, which began on the 15th of November 1824 and lasted for 5 days. Having been trained as a surveyor, he understood building techniques and materials. This along with his recruitment of various types of tradesmen helped him deal with the conflagration. His methodical approach to firefighting gained him a good reputation.

In 1833. He left Edinburgh and shifted to London, where he took over the running of the city’s London Fire Engine Establishment, the forerunner of The London Fire Brigade. In October 1834, he was involved in tackling the fire that destroyed much of the Palace of Westminster. His reputation was already great when he attended the fire in Tooley Street on the 22nd of June 1861. Three hours after the fire broke out, he was crushed to death by a falling wall. It took two days to recover his body and he was given a hero’s funeral. The fire, which began in Cottons Wharf, continued to burn for a fortnight. The reasons for its long duration included:

“The first was that firefighters were unable to get a supply of water for nearly an hour due to the River Thames being at low tide. The second was that the iron fire doors, which separated many of the storage rooms in the warehouse, had been left open. It is believed that had they been closed, as recommended by James Braidwood, the Superintendent of the LFEE, the fire could have been contained, avoiding disaster.” (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Tooley-Street-Fire/)

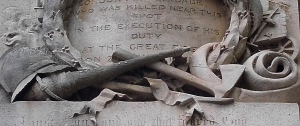

Overlooked by London’s recently constructed, glass-clad Shard, is short Cottons Lane that leads north from Tooley Street. Where these two roads meet, there is a sculptural plaque high up on a wall. It depicts a wreath entwined with a firefighting hose pipe. Behind the wreath, the artist carved the façade of a building with smoke billowing out of its windows. There also depictions of other tools used to fight fires in the 1860s when this memorial was constructed. Within the wreath. there are words:

“To the memory of James Braidwood, superintendent of the London Fire Brigade, who was killed near this spot in the execution of his duty at the great fire on 22nd June 1861” This is not the only memorial to Braidwood. Others, which I have not yet seen, can be found in Edinburgh and in Stoke Newington’s Abney Park, where Braidwood was buried.

January 8, 2022

Marconi slept here

DURING A SHORT VISIT to Chelmsford in Essex, we noticed an old hotel The Saracens Head. Situated in the centre of the city – yes, Chelmsford is a city; it has a fine cathedral – it bears a commemorative plaque which states that the inventor of radio Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937), founder of the Wireless Telegraph Company, stayed at the hotel between 1912 and 1928, when he made visits to his New Street factory in Chelmsford. Marconi made the city a place that was to change the world. It is hard to imagine how our world would be today without radio signals.

I wondered why he had chosen Chelmsford to site his factory. The only explanation I can find is that Marconi needed electricity for his factory and that Chelmsford had a good supply of it. In any case, his factory provided work for many (up to 6000) people in the city.

As for The Saracens Head hotel, I have not yet stayed there, which might be a good thing as it receives many poor reviews on Tripadvisor.

Prior to establishing his factory in Chelmsford, he lived in a terraced house near London’s Westbourne Grove, at number 71. He lived there between 1896 and 1897. That was 2 years after he had made the world’s first demonstration of radio transmission. He arrived in London from Italy in 1896 because few in his native land could see much of a future in what he had demonstrated.

January 7, 2022

Chemistry

Many people considered father to be charming, amusing, interesting, and kind, all of which he was. Many women found him attractive and some of them became romantically involved with him, but only about two years after my mother died. I was pleased because these interactions appeared to elevate his mood.

One of the first serious relationships that I was aware of involved Dad and ‘M’, a former home help from Scandinavia, who had lived with us for at least two years back in the early 1960s. M lived in Scandinavia but visited Dad in London several times. Although I had liked her a great deal when she was looking after my sister and me, my opinion of her had muted considerably when I saw her again many years later whilst she was visiting Dad.

On one of her visits, my sister kindly drove Dad and M down to Brighton for the day. She said that the amorous couple sat in the rear of her Volkswagen ‘Beetle’ and hardly uttered a word either to each other or to my sister, who felt that she had become a chauffeur rather than a daughter.

Whenever I was staying at Dad’s home for the weekend, I used to hear him speaking to M on the ‘phone. I knew that he was talking to M because he spoke in a tone that differed from his normal one. One Sunday morning I was sitting in our living room after breakfast and could just about hear Dad speaking in this strange tone. When he had ended the call, Dad entered the living room, and said:

“You know, Adam, it’s always difficult breaking up with girlfriends.”

For a moment, I was lost for words. Then, I said:

“Well, Dad, I could not see that you and M had much in common.”

Walking towards the door, and pausing in the doorway, he turned to me and said: “That doesn’t matter. It’s chemistry, you know, Chemistry.”