Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 146

October 28, 2021

Just before a drama

October 27, 2021

Images of Africa in south London

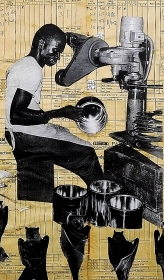

THE WHITE CUBE Gallery in London’s Bermondsey Street is overshadowed by the recently constructed (2013) glass-clad skyscraper, popularly known as ‘The Shard’. The gallery, a single-storeyed structure, contains a long wide corridor flanked by three vast exhibition spaces and a smaller bookshop. The exhibition spaces are deliberately sparsely decorated so as not to distract viewers from the usually wonderful contemporary artwork on display. At the end of the corridor, there is an auditorium in which videos relating to the existing temporary exhibition are screened. The current exhibition, which fascinated me and closes on the 7th of November 2021, is dedicated to displaying works by Ibrahim Mahama.

Mahama was born in Tamale, Ghana in 1987. He lives and works in the country of his birth but has exhibited widely in Africa and Europe. Not only are the works, which we saw at White Cube, exciting and intriguing visually but they also provide an interesting insight into the artist’s perception of modern Ghana and its past, when it was known as The Gold Coast.

Many of the works on display are gigantic collages, which from afar look like interesting abstracts or even modern tapestries. Closer examination of these reveals that the artist has glued fragments of photographs onto a background of usually either old maps of his country and/or a latticework consisting of numerous production order dockets issued by The Ghana Industrial Holding Company. Photographs of fruit bats in various poses often run around the fringes of the collages or appear within their main body. Photographs of aspects of life in Ghana are glued onto the backgrounds. Often, they have been trimmed so that the backgrounds intrude, and the photographs appear to merge or mingle with them. I felt that this was particularly effective when the map backgrounds mingled with the trimmed photographs, making me think that the maps were being brought to life. Also, they give the impression of modern Ghana emerging from the out-of-date maps. I was also impressed by one collage showing images of flying bats glued onto a sea of old order dockets: wildlife contrasting with man’s industrial enterprise.

One half of the largest display space is dedicated to a fantastic art installation. About 100 old-fashioned wooden school desks are arranged in rows facing a line of black boards to create the illusion of an enormous classroom. On each desk, there is an old-fashioned electric sewing machine. Every few minutes some of the sewing machines begin operating, creating a wonderful, loud noise, which varies as different groups of machines are activated and then silenced. Sewing machines, so the leaflet issued by the gallery inform us, were often used in Ghana by labourers wanting to learn a new trade. This exhibit aims, amongst other things, to resurrect the ghosts that Mahama feels reside within these discarded machines.

In the auditorium, a short video projected onto two neighbouring screens continues the artist’s interest in sewing machines. On one of the screens, the video shows in close-up the innards of sewing machines being cleaned and oiled. Simultaneously, the video on the neighbouring screen shows workmen doing messy maintenance work through a manhole cover and beneath the ground. The circular manhole cover is mirrored in the other video by the small circular orifice through which the innards of the sewing machine are maintained. Odd subjects, but well filmed and fascinating visually.

I am neither an art critic nor a sociologist, nor whatever it takes to ponder the deeper meaning and messages that the artist is trying to convey, but I enjoyed the exhibition greatly without having to worry about its deeper intellectual content. Visually, everything on display was exciting and often quite novel: a feast for the eyes and ears. If you can get to see this show, I am sure that you will not leave it unaffected by its impact. And, after feasting your ears and eyes at the gallery, I recommend a short walk down Bermondsey Street to treat your taste buds and olfactory sense to Vietnamese food, magnificently prepared, at Caphe House.

October 26, 2021

They are only there for the beer

DESPITE LIVING IN KENT for eleven years and having visited the county numerous times, it was only in October 2021 that I first stepped inside an oast house. Dotted all over the county with their tall conical (sometimes pyramidical) roofs surmounted by distinctive cowls, they play(ed) an important role in the production of beers.

An oast house with conical roof

An oast house with conical roofHops are the flowers (or seed cones) of the hop plant known by botanists as Humulus lupulus, a member of the Cannabaceae family of plants, whose members include Cannabis, the plant which is the source of marijuana. Only the flowers of the female hop plant are used in beer making. When dried to a well-defined degree, hops are added to the beer-making process both to add flavour and because of their antibacterial effects that prevent unwanted organisms growing whilst the beer is being brewed.

Traditionally in England, hops are dried out in oast houses. Picked hops are laid out on perforated drying floors in the upper levels of the oast house. A wood or charcoal fired kiln on the ground floor of the oast house produces hot air that drifts upwards through the layers of drying hops and then escapes through the cowl at the top of the oast house’s conical roof. The cowl has a vane that catches the wind and rotates the cowl so that the wind continuously draws the smoke from the kiln up through the oast house. The air that carries the smoke upwards is drawn into the oast house through perforations in the brickwork at the lower levels of the building. The tall conical design of the roof increases the draught of air through the hops. The drying process must be carefully monitored so that the hops are removed before they are dried out too much.

The earliest known record of hop cultivation was in a document dated 736 AD. It referred to hops being grown in Germany. The use of hops in beer production seems to have taken off in a big way by the 13th century. Before hops became used routinely in beer production, a mixture of herbs and flowers, known as ‘gruit’, was used for the same reason as hops. In Germany, hops became favoured over gruit in the early 16th century because unlike the latter, which were subject to taxation, the former were not (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hops).

Hops were introduced to England during the 16th century. The oldest description of an oast house (more accurately, a building for drying hops) was written in 1574. What was described was different in design to what we recognise as an oast house today. The earliest surviving oast house was built sometime during the following century. Today, hops are no longer dried in oast houses. They are processed in industrial premises that are not nearly as picturesque as oast houses, many of which have now been repurposed as dwellings and for other uses.

On the estate of Sissinghurst Castle, a former manor house rather than a castle, a set of former oast houses has been tastefully modified by the National Trust to create an exhibition space that includes information about oast houses and hop drying. Although the kilns are no longer present, the internal structures of the tall roofs have been preserved. By entering the exhibition space, I managed to see inside an oast house for the first time. I would be curious to see within an oast house that still contains its kiln and other equipment, but what I saw at Sissinghurst began to quench my thirst for knowledge about these curious looking buildings, which were only there for the beer and can be seen throughout the landscape of Kent.

October 25, 2021

The Zigzag path

MUCH OF FOLKESTONE, a seaside town in Kent, is perched on slopes leading down to cliffs overlooking the shoreline. The Leas, a wide promenade running along the top of the cliffs to the west of the centre of the town, affords fine views of the beaches and rocks far beneath it. Various staircases, a lift (out of action nowadays), and paths lead from The Leas down to the seashore and the park that runs alongside it. The most fascinating of these, The Zigzag Path, begins close to a cast-iron bandstand a few yards west of the statue of the scientist/physician William Harvey. I loved it so much that I walked down it three times in the three days we spent in Folkestone recently.

With five hairpin bends and a couple of short tunnels as well as blind ending caves, The Zigzag Path takes pedestrians down from the Leas at 150 feet above sea level to lower than 42 feet above the sea. The path is like a winding mountain road in miniature and provides endlessly changing views of the seashore and the trees and other vegetation growing near it. In more detail:

“The path is in five sections, and covers a substantial vertical area of about 75 metres across and 50 metres high. It incorporates steps, seats, plant pockets, low walls, and with tunnels, arches and caves at each turn.” (https://pulham.org.uk/2014/10/13/chapter-40-1920-21-the-leas-zigzag-path-folkestone-kent/).

The steep path was built for Folkestone Corporation in the early 1920s. The first attempt was not brilliant. So, the Corporation employed Mr Pulham of the company of James Pulham & Son, who specialised in the construction of rock gardens, follies, and grottoes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Pulham_and_Son). The company’s founder, James Pulham (1820-1898) was the inventor of a manmade (anthropic) rock-like material known as Pulhamite. This composite material simulates the appearance of natural rock so successfully that sometimes geologists are fooled by it. Pulhamite is a mixture of sand, Portland cement, and clinker, which is sculpted over a core consisting of rubble and crushed bricks (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulhamite). The Zigzag Path was built with Pulhamite. While walking down the path, I spotted several places where the surface of the Pulhamite had worn away leaving fragments of brick exposed. If I had not seen this, I would have found it difficult to believe that the path was not created using natural rock. Recently, interesting ironwork railings have been added to the side of path facing the sea. These incorporate metal features that resemble plant tendrils wrapping around a support.

The wonderful Zigzag Path is just one of many of the Pulham’s ornamental creations. A full listing can be found in “Rock Landscapes: The Pulham Legacy: The Pulham Legacy: Rock Gardens, Grottoes, Ferneries, Follies, Fountains and Garden Ornaments” by Claude Hitching and Jenny Lilly. A visit to Folkestone would not be complete without experiencing the beautiful and rather fantastic Zigzag Path, preferably by descending it. If you decide to ascend it, you will have done sufficient exercise not to need to visit the gym that day.

October 24, 2021

Blood on the wall

GRIPPING A HEART with the fingers of his left hand and his right hand on his chest, he stands in knee breeches, motionless on a plinth and staring out to sea. This bronze figure is a statue of the great scientist and first to give a scientific description of the way blood circulates through the heart and blood vessels, William Harvey (1578-1657), who was born in Folkestone, Kent, where his sculptural depiction stands. The commemorative artwork was created by the sculptor Albert Bruce-Joy (1842-1924) and made in 1881.

The heart in Harvey’s hand

The heart in Harvey’s handSon of a Folkestone town official, William Harvey began his education in the town, where he learned Latin. Next, he attended The Kings School in nearby Canterbury before matriculating at Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge. After graduating in Cambridge in 1597, he enrolled at the University of Padua in northern Italy. There, he graduated as a Doctor of Medicine in 1602. Harvey became a physician at London’s St Bartholomew Hospital, and later (1615) became a lecturer in anatomy. In addition to his teaching activities, he became appointed Physician Extraordinary to King James I. It was in 1628 that he published his treatise, “De Motu Cordis”, on the circulation of the blood, work that remains unchallenged to this day. In 1632, he became Physician in Ordinary to the ill-fated King Charles I. In 1645, when Oxford, the Royalist capital during the Civil War, fell to the Parliamentarians, Harvey, by now Warden of Oxford’s Merton College, gradually retired from his public duties. He died at Roehampton near London and was buried in St. Andrew’s Church in Hempstead, Essex.

Folkestone, formerly a busy seaport, has restyled itself during the last few years. It has become a hub for the creative arts. Works by various contemporary artists, some quite well-known including, for example, Cornelia parker, Yoko Ono, and Antony Gormley, are dotted around the town and can be viewed throughout the year. Every three years, even more art can be found all over the town as part of The Creative Folkestone Triennial. This year, 2021, it runs from the 22nd of July until the 2nd of November. As one wanders around the town, one can spot artworks in both obvious locations and some less easily discoverable places. This year, the London based artistic couple Gilbert and George have exhibited several of their colourful and often thought-provoking images. And this brings me back to William Harvey.

High on a wall just a few yards behind the statue of Harvey, there are two images by Gilbert and George. Both were created in 1998. One is titled “Blood City” and the other “Blood Road”. Both relate to blood, its corpuscles, and its flow. It is extremely apt that they have been placed close to the image of the man who did so much to increase our understanding of blood and its circulation through the human body.

October 23, 2021

A miniature man with a big story

FROM A DISTANCE, the small stone statue in Folkestone’s Kingsnorth Gardens looked like an oriental character, maybe a Hindu god or a Chinese warrior. Getting near to it, you can see that it depicts a small man in armour. The sculpture’s left hand rests on his waist and he holds a stout staff in his right. On the top of his hat or helmet, there perches a female figure, which on further examination proves to be a sphinx. And what fascinated me most was seeing that his breastplate has a double-headed eagle in bas-relief. This curious statue is supposed to be a depiction of Sir Jeffrey Hudson (1619 – c1682).

Jeffrey Hudson

Jeffrey HudsonHudson was baptised in Oakham in the county of Rutland, which used to be one of England’s smallest counties. Maybe, this was appropriate because Jeffrey was only 30 inches tall when he reached the age of 30 years. However, he eventually reached the height of 42 inches (www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1129288). Despite his shortness, which might have resulted from a disorder of the pituitary gland, he was perfectly proportioned and therefore a dwarf. Small as he was, his life story (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_Hudson) reads like a tall tale.

Aged 7 years, Jeffrey was presented to the Duchess of Buckingham, who welcomed him into her household. Soon after his arrival in this august household, the Duke and Duchess entertained King Charles I and his young wife, Queen Henrietta-Maria (1609-1669), at a party in London. The highlight of the evening was the arrival of an enormous pie:

“…two footmen enter the hall carrying a glorious pie, gilded in gold leaf, 2ft high and 2ft wide. The pie is placed before the queen and, as if in labour, it begins to move. A small hand pops through the crust, and a fresh-faced boy emerges with a cheeky smile, dark brown eyes and light brown hair. He wears a miniature suit of armour and marches up and down the banqueting table waving a flag. He returns to the queen and gives a bow.” (www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/amazing-life-jeffrey-hudson-queen-henrietta-maria-dwarf/)

The queen was so delighted by the dwarf that the Duke and Duchess presented her with Jeffrey as a gift.

Jeffrey joined the collection of live ‘curiosities’ that the queen kept in her court. There were two other dwarves, a giant porter, and a monkey, to list but a few. As Jeffrey grew up, he was educated, learned to ride and shoot, and joined in the court’s leisure activities. After the Civil War broke out in 1640 Jeffrey travelled to France with the queen and members of her household. By 1644, Jeffrey had become fed up with being a ‘pet’, a ‘curiosity’, and the butt of cruel jokes. In October of that year, he challenged a man called Crofts to a duel. Out of contempt for tiny Jeffrey, Crofts brought water squirt guns to the duel. However, when hit in the forehead by Jeffrey’s water emitting weapon, Crofts fell down dead.

Duelling was already banned in France. The queen sent Jeffrey back to England. Soon after leaving her court, Jeffrey was on a ship that was attacked by Barbary pirates. He was captured and enslaved. Nothing is known about his life in slavery. However, he is recorded as being back in England in 1669. He lived in Oakham for several years, returning to London in 1676. Convicted for being a Roman Catholic, he spent a long time in the Gatehouse Prison, which used to be in the gatehouse of London’s Westminster Abbey. He died a pauper sometime after being released. Thus ended the life of a very small man.

We wondered what Hudson’s connection with Folkestone was and why the town is blessed with a statue depicting him as he must have looked when he emerged from a pie. It turns out that he has no known connection with the town, but his statue has stood there since Victorian times and was placed in Kingsnorth Gardens in 1928. What we see today is a replica of the original, which had deteriorated over the years (www.gofolkestone.org.uk/news/welcome-return-of-sir-jeffery-hudsons-statue-to-kingsnorth-gardens/). As for the double-headed eagle on the statue’s breast plate and the sphinx on his head, I need to look into this at a later date.

October 22, 2021

A sea creature in stone at Richmond upon Thames

ON A TERRACE that overlooks the River Thames at Richmond there is a curious souvenir of the past. The so-called Fish Marker Stone was dug up in the 20th century. It is named thus because there is a carved fish or sea creature on top of it. Now no longer visible because it has worn away, the stone’s inscription bore the words “To Westminster Bridge 14 3/4 miles”. The stone is believed to have marked a fare stage for boatmen carrying passengers along the river.

October 21, 2021

Royal remains

WE VISIT RICHMOND regularly to see a couple of friends, with whom we almost always take a stroll, usually somewhere reasonably near their home. They know that I love seeing places that I have never visited before and almost always they take us to see something that they feel might interest us. On our most recent walk with them, taken in October 2021, we began by walking across Richmond Green, taking a path that was new to us. At the western edge of the green, we crossed a road and immediately reached a Tudor gateway that leads into an open space surrounded by buildings. The open space is on the site of a now mostly demolished royal residence that was particularly liked by Queen Elizabeth I.

The royal residence was Richmond Palace. It was built by King Henry VII, when the 14th century Shene Palace, which used to stand on the site, was destroyed by fire in December 1497. Henry VII built a new palace on the same ground plan of Shene Palace. Richmond Palace, as the new building was named, was used continuously a royal residence until the execution of King Charles I in January 1649.

On a wall facing a pathway leading from the old gatehouse to the River Thames, there is a commemorative plaque with the following carved on it:

“On this site extending eastwards to cloisters of the ancient friary of Shene formerly stood the river frontage of the Royal Palace first occupied by Henry I in 1125…”

It adds that Edward III, Henry VII, and Elizabeth I all died in the palaces that stood on this riverside site in Richmond.

After Charles I lost his head, the palace, like many other parts of the royal estate, was sold by the Commonwealth Parliament led by Oliver Cromwell. Much of its masonry was sold. According to an informative source (www.richmond.gov.uk/media/6334/local_history_richmond_palace.pdf):

“While the brick buildings of the outer ranges survived, the stone buildings of the Chapel, Hall and Privy Lodgings were demolished and the stones sold off. By the restoration of Charles II in 1660, only the brick buildings and the Middle Gate were left.”

The same source relates that after being owned by the Duke of York, who became King James II, and after he was deposed:

“The remains of the palace were leased out to various people and, in the early years of the 18th century new houses replaced many of the crumbling brick buildings. ‘Tudor Place’ had been built in the open tennis court as early as the 1650s, but now ‘Trumpeters’ House’ was built in 1702-3 to replace the Middle Gate, followed by ‘Old Court House’ and ‘Wentworth House’ (originally a matching pair) in 1705-7. The Wardrobe building had been joined up to the Gate House in 1688-9 and its garden front was rebuilt about 1710. The front facing the court still shows Tudor brickwork as does the Gate House. ‘Maids of Honour Row’ replaced most of the range of buildings facing the Green in 1724-5 and most of the house now called ‘Old Palace’ was rebuilt about 1740.”

During our recent perambulation with our friends, we saw most of the buildings listed in the quote above but not the Maids of Honour Row. They also pointed out that Richmond Green, across which we walked, was used for jousting tournaments in mediaeval times. Today, this pleasant green space close to Richmond’s main shopping street is used for more peaceful purposes including walking, both human beings and their canine companions.

Once again, a visit to our friends in Richmond has resulted in opening our eyes to new places of great interest, and for that we are most grateful.

October 20, 2021

Once it was owned by Rothschild

ACCIDENTALLY, WE BOARDED a bus, which we believed would take us to Gunnersbury station in west London, but instead it took us to the edge of Chiswick Business Park furthest away from the station. This meant that we had to walk through the business park, and this was no bad thing.

The business park has been built on land that used to be owned by the Rothschild family, who owned nearby Gunnersbury Park for much of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th. In 1921, a bus company built a 33-acre bus maintenance establishment on the site where the Rothschild’s used to have orchards and where today the business park stands. This was closed in 1990, and various architects, including Norman Foster, drew up plans to develop the site with buildings around a central ‘piazza’.

Eventually, after gaining planning permission, the first building was completed at the end of 2000. Gradually, the rest of the buildings were constructed. The site was completed in 2015. The result is spectacular. The buildings are uncompromisingly modern, almost sculptural, and, most importantly, pleasing to the eye. They are arranged around an attractive lake or pond, complete with waterfalls, a bridge, and some metal sculptures. A number of small spherical glass and metal ‘meeting pods’ have been placed close to the water feature and there are several refreshment kiosks dotted around the place.

In 2019, a long footbridge, suspended from a series of giant oxidised steel hoops was constructed between the place where our bus (route 70) terminated within the business park and Chiswick Park Underground station. It is an elegant piece of engineering.

We have often passed the Chiswick Business Park whilst travelling by car or bus along Chiswick High Road that forms its southern border, but never bothered to walk in it. Today, we did, and it was a pleasant new experience.

October 19, 2021

Small injection, small world

WE JOINED A SMALL queue at the vaccination centre, or “hub” as it calls itself, early one sunny but cool morning. All of us were waiting to receive our covid 19 booster vaccine, six months having elapsed since receiving the second of our first two ‘jabs’. Eventually, we were invited into the local hospital, in which the hub is located.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://yamey.files.wordpress.com/202..." data-large-file="https://yamey.files.wordpress.com/202..." src="https://yamey.files.wordpress.com/202..." alt="" class="wp-image-7320" width="227" height="358" />Photo by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels.comI was directed to a cubicle where a lady, a volunteer vaccinator, was seated. After having been asked some preliminary medical questions and given some advice about possible aftereffects of the vaccine, she said to me, having already noted my name:

“Are you South African?”

“My parents were,” I replied.

“I know a Craig Yamey,” she said.

“He is a relative of mine.”

Then, she said:

“I knew an old gentleman, a Mr Yamey married to a Greek lady.”

“He was my father,” I replied, adding: “How do you know him”

It turned out that the lady’s mother lives next door to where my father lived for the last 27 years of his long life.

Having established that and just before giving me the injection, quite painlessly I should add, she said:

“In that case, I must take very special care of you.”

The world can seem remarkably small, don’t you think?