Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 156

July 8, 2021

From Cornwall to the Himalayas

THE CORNISH VILLAGE of St Kew, though small, is an extremely attractive place to visit. Its name derives from that of a Welsh saint called ‘Cywa’ who might have been the sister of Docca, who founded a monastery near the present village of St Kew. In the centre of the village, close to a bridge crossing a stream, there is a lovely pub, The St Kew Inn, which was built in the 15th century (www.stkewinn.co.uk/). We stopped there for much-needed liquid refreshment on a hot afternoon in late June 2021. Close to, and on higher ground than, the pub, there is another 15th century edifice, the parish church of St James.

The church contains much to fascinate the visitor including fine stone and wood carvings, remnants of pre-Reformation stained-glass, a carved stone with ancient Ogham script, a carved gravestone bearing the date 1601 and a depiction of a lady in Tudor dress, and wooden barrel-vaulted ceilings. All of this and more makes St James one of the loveliest churches we have seen in Cornwall. Although I was highly enchanted by all this antiquity, it was one modern memorial in the church that intrigued me most.

The

monument on the inside of the north wall of the church reads:

“In

memory of Alison Chadwick-Onyskiewicz of Skisdon, St Kew. Born May 4th 1942. Artist and Mountaineer. She made the first ascent

of Gasherbrum III. 26090 ft. And died on Mt Annapurna, Nepal, on 17th

October 1978.”

Well,

I was not expecting to find this when I entered the church at St Kew.

From

Alison’s obituary on the alpinejournal.org.uk website, I have extracted the

following information about her. She was born in Birmingham but spent her

formative years in Cornwall. Whilst studying at the Slade School of Art at

University College, London, she became interested in mountaineering. Her

climbing experience began in North Wales, before gaining experience in the Alps

and rock faces in Devon and Cornwall.

In

1971, she married a well-known Polish mountaineer, Janusz Onyskiewicz, who was

also a mathematician and twice Poland’s Minister of National Defence (1992-1993

and 1997-2000). In the 1980s, he was a spokesman for the Solidarity Movement. Alison

lived in Poland after she married him in Bodmin, Cornwall. She and Janusz were two

of the four members of the Polish expedition that conquered Gasherbrum III,

which was at the time the highest yet unclimbed peak. The obituary notes:

“Alison’s

climbing ethics were always of the highest standard and on high mountains she wished

to compete with men on equal terms with the minimum of oxygen and Sherpa assistance.

Perhaps it was for this reason that she chose to accept an invitation to join

the 1978 American Ladies Expedition to Annapurna rather than accept a place on the

more glamorous Franco/Austrian Expedition to Everest. On the Annapurna

expedition Alison’s contribution was crucial, leading the ice-arete between

camps 1I and III which proved to be the crux of the route. After the summit had

been reached on 15 October, Alison and Vera Watson were killed in a fall while

making a second summit bid.”

Although

Janusz was in the Himalayas 40 miles away from the scene of the fatal accident,

news of it took two weeks to reach him.

So,

that is, in brief, the story of the lady commemorated by an oval slate memorial

in St James Church in St Kew. I have yet to discover where she was buried and

who placed the memorial in the church. Discovering this connection between St

Kew and the Himalayas was yet another delightful surprise that enhanced my

enjoyment of the southwestern county of Cornwall.

July 7, 2021

Overlooking the harbour that was attacked by the Spanish

THE CHURCH OF St Mary’s in Cornwall’s western town of Penzance overlooks the harbour and much of the town. Its site has been a place of worship since at least 1321, when there was a chapel on the spot. Between the 2nd and 4th of August 1595, Penzance, along with Newlyn, Mousehole, and Paul, was sacked by Spanish forces under the command of Carlos de Amésquita. After causing much damage, Carlos celebrated mass in the chapel of St Mary at Penzance, an edifice he had spared from destruction.

The chapel was enlarged in 1662-1672 and then again in 1782. Until 1871, when a new parish was created, the enlarged chapel had been a ‘chapel of ease’ for the parish of nearby Madron. Reverend Thomas Vyvyan began replacing the old chapel with a new church in 1832. Its architect was Charles Hutchens (c1781-1834), of Torpoint near Plymouth. In August 1832, the old chapel was demolished, and worshippers used a temporary wooden building whilst the new church was being constructed (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1220507). The new church, gothic revival in style, was ready for use in November 1835.

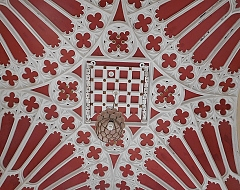

The church’s interior was damaged by fire caused by an arsonist in 1985 but was restored the following year. Being built of granite, the church looks older than it is at first sight. However, the design of its windows is typical of gothic revival. Inside the church, there are features that exemplify the very best of the gothic revival style, which reminded me of that masterpiece of the style, Strawberry Hill at Twickenham (near London). Having been restored after the fire, they are looking in superb condition.

I am glad that I climbed the several staircases that ascend the steep slope from the seashore near Penzance’s art-deco Jubilee Bathing Pool to the church. For those who prefer not to climb, the church can also be accessed by walking down Chapel Street from the central shopping area of Penzance. However, after seeing the church you will have to climb back up to where you started, but on the way, you might pause to look at the Chapel Street Methodist Church, with its odd but harmonious mixture of architectural styles, built in the mid-19th century. Or, if you have had enough of ecclesiastical architecture, you could drop into The Turks Head Inn for some refreshment spiritual or otherwise. The pub’s name reflects the fact that Cornwall used to be raided by Moorish pirates, who captured some of the locals and made them enter slavery, but do not let that put you off entering the place. Oh, and whilst you are on Chapel Street, do not miss seeing the unusual Egyptian House near the top of the thoroughfare.

July 6, 2021

The most southern city in England

AN HOUR IN TRURO is hardly enough to get to know the county town of Cornwall well, but it is long enough to discover that the city’s centre is attractive and interesting. In 1876 the Diocese of Truro was founded and in the following year, it gained the status of ‘city’, making it the southernmost city in mainland Britain. Until the diocese was established, the county of Cornwall including the Scilly Isles and a couple of parishes in Devon were in the Diocese of Exeter. Given that the Christian faith was well established in this southwestern part of England at least 100 years before the first Archbishop of Canterbury was appointed, it was high time that Cornwall had its own diocese and archbishop.

Truro Cathedral

Truro CathedralBetween 1880 and 1910, a gothic revival cathedral designed by John Loughborough Pearson (1817-1897) was constructed on the site of the 15th century parish church of St Mary. Parts of this old church were incorporated into the new cathedral and the top of its granite spire stands in a garden next to it. One of only three British cathedrals with three spires, Truro’s cathedral was the first new cathedral to be built in England after many centuries. Although a relatively recent structure compared with many of Britain’s other cathedrals, it is a fitting design for the mediaeval heart of the city with its narrow winding streets.

The name Truro might be derived from the Cornish words meaning ‘three rivers’ or ‘the settlement on the River Uro’. In any case, Truro has a river running through it, which helped stimulate the growth of the city’s prosperity. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the tin mining industry added to Truro’s wealth. Lemon Street, where we parked, is evidence of that; it looks like a Georgian street in Bath or some parts of London. The arrival of a direct railway line between the city and London in the 1860s provided a further boost to the city’s success. Earlier in mediaeval towns, Truro, which is inland and therefore difficult to reach by seaborne foreign invaders, became an important port. In addition, it was a stannary town, where revenue from the tin industry was collected, yet another source of the town’s wealth.

Our brief first visit to Truro (at the end of a long day out) has whetted my appetite for another lengthier exploration of the city, which at first sight seems to have many interesting features to excite tourists who have an interest in history.

July 5, 2021

A viaduct in Cornwall and a man who died for his country

THE SMALL CORNISH village of Luxulyan has a fine old parish church, which is dedicated to Saints Ciricius and Julitta, both of whom are new to me. This edifice was built in the 15th century and restored in the 19th (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1158407). The northern aisle of the church was filled with used books for sale when we visited it. A weathered Cornish cross stands close to the west end of the church. During the 19th century, this was brought to its present location from Three Stiles (near Consence). The church and its churchyard, along with the tiny village are charming, but what caught my eye and raised my curiosity was a building bearing the name ‘Captain TC Agar-Robartes Memorial.’

Treffry Viaduct near Luxulyan in Cornwall

Treffry Viaduct near Luxulyan in CornwallThe name Agar-Robartes intrigued me. My interest in it increased when I saw a small stone memorial near the River Fowey in Lostwithiel. It bore the words:

“Royal British Legion, Lostwithiel Branch, 1932-1997. Opened by Lady Robartes.”

Things became clearer after visiting the magnificent Lanhydrock House, originally constructed in the 17th century, and reconstructed quite faithfully after a huge fire in 1881. The house was created by John Robartes (1606-1685), 2nd Baron Robartes of Truro, 1st Viscount of Bodmin, and 1st Earl of Radnor. One of his many descendants, Anna Maria Hunt (1771-1861) married Charles Bagenal-Agar (1769-1811). One of their three sons, Thomas James Agar-Robartes (1808-1882), assumed the surname ‘Robartes’ in 1822 and tacked it on to his Agar surname. One of his ten grandchildren was Thomas Charles Reginald Agar-Robartes (1880-1915), the ‘TCR Agar-Robartes’, whose name is on the building in Luxulyan.

Thomas was educated at Eton and Christ Church College, Oxford. He was elected to represent the South-East Cornwall constituency as its MP in 1906. However, he was unseated a month after the election because of infringing some electoral regulations. He had been found guilty of bribery and other offences. Nevertheless, he was re-elected in 1908. His election campaign was based on support of free trade and reform of temperance laws. In August 1914, Thomas signed up as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Bucks Hussars, and then in 1915, wanting to see action on the battlefront, he left for France as an officer in the 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards. In June 1915, he was promoted to become a captain. During the Battle of Loos in September 1915, he was shot in no-mans-land and never recovered.

The building, a working man’s institute and reading room in Luxulyan, which bears Thomas’s name, was first conceived in 1913, but only began to be used as such in 1924, when the edifice was completed. Naming it after Thomas is explained on a website page about the building (www.luxulyanpc.co.uk/Luxulyan_Memoria...

“ Tragically, as we know, young Tommy Robartes of Lanhydrock died after receiving wounds rescuing a comrade from one of those fields of battle. He had been well known and liked in the village, often coming to visit, accompanying the land agent dealing with tenants. The village picked up its interrupted thoughts on the Institute and Reading Room idea; whether the idea of a Memorial to Tommy, or just asking the Lanhydrock estate for a piece of land came first, is not clear, but it was agreed that a piece of land from the estate for a Memorial Institute was acceptable to all.”

Having already offered £50 towards building the Memorial institute, Dr Nathaniel T Coulson then offered a further £100 on condition that Thomas Agar-Robartes’s name was on the hall. Dr Coulson, who is described in the website, interested me because of his profession:

“He was born in Penzance in April 1853, abandoned by his drunken father at the age of 10 years and bound over to the farmer at Penquite Farm, Lostwithiel. He then spent some years in the British Navy and first arrived in San Francisco in 1875. For a while he worked for a stock-broking firm and wrote for several daily newspapers. In 1884 at the age of 30, he became a student at the dental department of the University of California, where he graduated after two years, receiving his degree as a Doctor of Dental Surgery. He was a member of several fraternal organisations, and generous with donations to many worthy causes. Among others in England, he helped finance the establishment of Coulson Park, Lostwithiel, in 1907. He travelled back here on several occasions, also visiting India after his retirement…”

So, that explains the hall that we saw in Luxulyan. I am not at all sure which ‘Lady Robartes’ is the one whose name appears on the British Legion monument in Lostwithiel, which bears the words “Opened by Lady Robartes”. If a Lady Robartes opened the branch in 1932, who was she? Only one of Thomas’s brothers married, Arthur (1887-1974). His wife, Patience Mary Basset, whom he married in 1920 might have been the ‘Lady Robartes’. Alternatively, she might have been one of Thomas’s sisters: Mary Vere (1879-1946) or Julia (1880-1969) or Edith (1888-1965) or Constance (1890-1936). If on the other hand the words refer to the inauguration of the monument in 1997, then I cannot offer any suggestions.

Luxulyan is worth visiting not only to see the things I have already mentioned, but also the impressive, massive, granite combined aqueduct and viaduct near to the village. It carries water and a railway track over the River Par. Known as the Treffry Viaduct, it was completed in 1844 and designed by the engineer and mining entrepreneur Joseph Treffry (1782-1850).

Until we visited Luxulyan, I had never heard of the Agar-Robartes family. Once again, visiting Cornwall has resulted in finding places and persons of great interest. The more I see, the more I want to know.

July 4, 2021

Lost and found … in Cornwall

MY COUSINS IN CORNWALL live not far from a place called Withiel. The mainline train from London to Penzance usually stops at a station called Lostwithiel. The latter is just over 7 miles southeast of Withiel as the crow flies. Yesterday, the 26th of July 2021, we decided to visit both Withiel and Lostwithiel. Despite its name, Lostwithiel on the River Fowey is much easier to access than Withiel, which is deep in the Cornish countryside.

Mediaeval arch in Lostwithiel

Mediaeval arch in LostwithielThe ‘lost’ in Lostwithiel has little if anything to do with being unable to be found. There is agreement that ‘lost’ is the Cornish word for ‘tail’. It is likely that Lostwithiel derived from the Cornish ‘Lost Gwydhyel’, meaning ‘tail end of woodland’. The village of Withiel is known as ‘Egloswydhyel’ in the Cornish language. This means ‘church in woodland’. Having found out that Lostwithiel is not actually lost nor ever has been, I will compare the two places.

Withiel, far smaller than Lostwithiel, is small village with a fine old church, St Clements and a few, about twenty at most, houses arranged around a rectangular open space. The parish church, which I have yet to enter, originated in the 13th century. It was rebuilt in granite in the 15th and 16th centuries and looks far too large for such a small village and its neighbouring communities including one called Withielgoose. The rebuilding was instigated by Thomas Vyvyan (late 1470s – 1533), the penultimate Prior of Bodmin before the Reformation. He was a Cornishman educated at Exeter College (Oxford), who was instituted in the rectory of Withiel in 1523, and then at St Endellion Church in 1524. Withielgoose, which is tiny place that includes the word ‘withiel’, has nothing to do with geese. The name derives from the Cornish words ‘gwyth’, meaning trees; ‘yel’, of unknown meaning; and ‘coes’, meaning ‘wood’.

Tiny Withiel has at least one interesting historical figure apart from Thomas Vyvyan, Sir Bevile Grenville (1594/95-1643). Educated at Exeter College (Oxford), he was a Member of Parliament and a Royalist. He was killed at The Battle of Lansdown (5th of July 1643) in the English Civil War. The historian of the Civil War Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (1609-1674), who served the Royalists during the conflict, wrote of Sir Bevile:

“…to the universal grief of the army, and, indeed, of all who knew him. He was a gallant and a sprightly gentleman, of the greatest reputation and interest in Cornwall, and had most contributed to all the service that had been done there.”

From small Withiel, we move to the town of Lostwithiel, an attractive place that seems not to have become as great a tourist attraction as have many other picturesque places in Cornwall. The town was established in the early 12th century by Norman lords, who constructed Restormel Castle nearby. It was a stannary town, which meant that it could manage the collection of ‘tin coinage’, a duty payable on tin mined in Cornwall. Most of what was collected entered the coffers of the Duchy of Cornwall.

In the 13th century, Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall (‘Edmund of Almain’; 1249-1300) built both the Great Hall in Lostwithiel and the town’s church tower. Edmund was son of Richard of Cornwall, 1st Earl of Cornwall and King of the Romans (king, not emperor, of the Holy Roman Empire) between 1257 and 1272. The tower is still standing as are also the remains of the Great Hall, built between about 1265 and 1300, making it one of the oldest non-ecclesiastical buildings in Cornwall. It was a large complex of buildings, which was badly damaged during the English Civil War. What remains is an interesting set of mediaeval buildings and the old Exchequer Hall, now known as ‘The Duchy Palace’. Later used as a Masonic Hall, some of its windows contain six-pointed stars as used by the Masons. A crest on one of its walls is the earliest version of that of the Duchy of Cornwall, which has long since been replaced by the plume of feathers used today. The Cornish born (in St Austell) and world-renowned historian Alfred Leslie Rowse (1903-1997) wrote that in the mediaeval era:

“… the real centre of Duchy administration was Lostwithiel; here the various offices, the shire hall where the county court met, the exchequer of the Duchy, the Coinage Hall for the stannaries’ and the stannary jail, were housed in the fine range of buildings built by Edmund, Earl of Cornwall…”

So, Lostwithiel was once important as an administrative centre, but it has now lost this role.

The River Fowey flows through Lostwithiel, passing meadows where people picnic, and children play. The river, though wide, is shallow enough for youngsters to play in safely. The river is crossed by a magnificent multi-arched, stone bridge, which is so narrow that it is only wide enough for one single motor vehicle. The crossing has six pointed arches. It was constructed in the mid-15th century. Its parapets were built in the 16th century and an additional flood arch was added in the 18th century (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1327324).

We wandered around Lostwithiel for a while and saw many fine old buildings apart from those already mentioned. One of them is the Museum, housed in the former Corn Exchange (a Georgian building), and the former Grammar School. We also spotted an ancient Cornish cross in the parish churchyard. Lostwithiel is a place to which I hope to return to spend more time there. In comparison to Withiel that is far more lost from sight, Lostwithiel has plenty to interest the visitor.

July 3, 2021

Two heads in Cornwall

BIRDS WITH TWO heads have fascinated me ever since I first became interested in Albania when I was about 15 years old. Just in case you did not know, the flag of Albania (and several other countries) bears an eagle with two heads. Another place that uses this imaginary bird with two heads as a symbol is a place I visit frequently: Karnataka State (formerly Mysore State) in the south of India. Currently (June 2021), unable to visit either Albania or India, we are on holiday in the English county of Cornwall. At least two Cornish families have employed this imaginary double-headed creature as a symbol: the Killigrews and the Godolphins. The famous banking family, the Hoares, also use the double-headed bird on their crest. A branch of this family might have originated in Cornwall ().

In the Kings Room at Godolphin House, Cornwall

In the Kings Room at Godolphin House, CornwallI do not know for sure when or why the two-headed bird was adopted by these leading Cornish families, but here is my theory. John (1166-1216), King of England from 1199 until his death, had a son, his second, called Richard (1209-1272). His older brother, who became King Henry III, gifted him the county of Cornwall, making Richard High Sherriff of the county as well as its duke. The revenues collected from his county made Richard a wealthy man. Cutting a long story short, Richard of Cornwall was elected King of the Germany in 1256, often a position held by candidates being considered for becoming Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. This allowed him to become known as the ‘King of the Romans’. He was the ruler (but not the emperor) of the Holy Roman Empire, a position he held until 1272, when he was replaced by Rudolf I of Habsburg (1218-1291). Richard hoped to become emperor, but never made the position. His crest bore a single-headed eagle, but that of the realm to which he aspired, The Holy Roman Empire, employed an eagle with two heads. At this point, I enter the realm of speculation. I suggest (with no evidence to back this up) that some noble families in Cornwall, who might have been associated with Richard, might have borrowed the double-headed eagle of Richard’s German kingdom for use on their family crests to enhance their family’s importance. Or, they might have used it in deference to Richard. But, as my late father-in-law often said, I am only thinking aloud.

Recently, we visited Godolphin House, a National Trust maintained property just over 4 miles northwest of Helston. Set in lovely gardens, the house is what remains of a building that dates to about 1475, built by John I Godolphin. It was part of a far larger building, much of which is in ruins. It has a good set of stone outhouses. Godolphin built his house about 7 years after the death of the Albanian hero Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu (1405-1468), also known as ‘Skanderbeg’, whose coat of arms, helmet, and seal includes a double-headed eagle. I do not know whether Skanderbeg was aware of the Godolphins, but it is possible that the reverse might have been the case, as much was written about the Albanian hero, even soon after his death, and many members of the Godolphin family were well-educated.

The name ‘Godolphin’ is derived from several earlier versions of the family’s surname. In 1166, there was reference to ‘Edward de Wotholca’. A record dated 1307 mentions the family of ‘Alexander de Godolghan’, who died in 1349. It was he who built the first fortified residence at Godolphin, the name that the family eventually adopted. John I Godolphin demolished the first dwelling and replaced it with what was the basis for the existing building.

The Godolphins of Cornwall included several notable figures. Sir Francis I Godolphin (1540-1608) constructed extensive defensive works to protect Cornwall and The Scilly Isles against Spanish incursions, as well as improving the efficiency of his tin mines. His son William Godolphin (1567-1613) was a loyal supporter of royalty during the English Civil War. It was said that the future King Charles II visited Godolphin House and stayed in what is now known as the ‘King’s Room’.

Sidney, 1st Earl of Godolphin (1645-1712) was involved in the Court and Parliament during the reign of Queen Anne, which ran from 1707 to 1714. His most important position was First Lord of the Treasury. During both Anne’s reign and that of her predecessor, King William III, he was strongly associated with the military career of John Churchill, the 1st Duke of Marlborough. Sidney’s son, Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin (1678-1766) was also a politician and a courtier. Although he was born in London, he represented the Cornish constituency of Helston, which is not far from Godolphin House. Francis worked his way up the governmental hierarchy to become Lord Privy Seal in 1735. a position he held for five years. In 1698, Francis married Henrietta (1681-1733), eldest daughter of the 1st Duke of Marlborough.

The Godolphins were spending hardly any time in Cornwall by the 18th century. From 1786, Godolphin House was owned by the Dukes of Leeds, who never lived there. Despite its now distant connection with the Godolphin family, their double-headed eagle can still be spotted around the house. There is a fine example in the Kings Room and several more on the hopper heads at the top of the rain collecting downpipes.

Whether or not birds with two heads fascinate you, a visit to Godolphin House, remote in the Cornish countryside, is well-worth making, not only to spot the mythical birds but also to enjoy fine architecture and wonderful gardens.

July 2, 2021

What’s in a name?

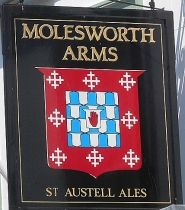

THE NAME MOLESWORTH immediately recalls a naughty schoolboy who cannot spell properly. Nigel Molesworth, a pupil in St Custards, a preparatory school, appears as a character in books by Geoffrey Willans (1911-1958) such as “Down with Skool”, “How to be Topp”, and “Whizz for Atomms”. However, for the Cornish town of Wadebridge, the name Molesworth has other significance.

One of the main shopping thoroughfares in Wadebridge is called Molesworth Street. The Town Hall was opened in 1888 by Sir Paul Molesworth (1821-1889). A pub called The Molesworth Hotel, a former coaching inn housed in a building that dates back to the 16th century, is located on the street named after Molesworth. The pub was only named as it is today in 1817. Previously, it had various names including The Fox, The King’s Arms, and The Fountain.

Wikipedia informs us that:

“The Molesworth, later Molesworth-St Aubyn Baronetcy, of Pencarrow near St Mabyn in Cornwall, is a title in the Baronetage of England. It was created on 19 July 1689 for Hender Molesworth.”

Hender Molesworth (c1638-1689) was a Governor of Jamaica from 1684 to 1687 and from 1688 to 1689. Pencarrow House is just under 4 miles southeast of Wadebridge. Each of the 2nd, 4th,6th, and 8th Baronets represented Cornwall or parts of the county in Parliament. The Molesworths were (are?) major landlords in the area around Wadebridge.

Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet (1810–1855), was the grandfather of Sir Paul, who opened the Town Hall in 1888. This edifice bears a weathervane in the form of a steam railway locomotive. After undertaking a ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, which lasted from 1828 to 1831, William made his way to Pencarrow, where he:

“…devoted time to establishing the Wadebridge-Bodmin Railway company. He engaged Hopkins the civil engineer to survey the land for the route with the prospectus for the formation of the Railway Company drawn up by Mr Woollcombe, from the family’s firm of solicitors.” (www.pencarrow.co.uk/story/sir-william-molesworth/)

This railway opened in 1834, was the first steam railway in Cornwall. It continued in service until 1979. The tracks have been removed but some of Wadebridge’s station buildings have been preserved,

William became interested in radical politics. In 1832, he was elected Member for East Cornwall, and re-elected in 1835. As an MP, he:

“…had joined a group named the ‘Philosophical Radicals’ who advocated various reforms such as universal education, disestablishment of the church and universal suffrage.”

Between 1837 and 1841, William, having alienated his Cornish electorate, sat in the House of Commons, representing Leeds. After falling out with his Leeds constituents on account of his views on foreign policy, he retired to Pencarrow, where he dedicated his time to improving the gardens.

In 1844, William married a widow, an opera singer Andalusia (née Carstairs), who died in 1888. The year after his marriage, William was elected MP for London’s Southwark constituency, a seat he held until his death. Amongst his positions whilst representing Southwark, he was Secretary for The Colonies during the last few months of his life. He had wished to be buried in his grounds in Pencarrow, but instead he was buried in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery.

Sir William and his family are deeply involved in the history of Wadebridge and it is right that the Molesworth name is so prominent in the town. From now onwards when I hear or read the name Molesworth, a naughty schoolboy with spelling problems will not be the only thing that springs to mind.

July 1, 2021

A filling station in rural Cornwall

THE LAST TIME that a person other than me put petrol into a car that I was driving was in August 2003 in South Africa, where self-service petrol pumps were then a rarity. In India, where I do not drive, vehicles are often filled by the garage attendants. Today (24th June 2021), we were driving along the A394 road in Cornwall when we spotted a petrol station, the modest-looking Double S Garage at Ashton, selling lower than average priced petrol. It was charging £1.26 per litre (currently the price of a litre in Cornwall ranges from £1.24 to £1.36).

I stopped by a pump and got out of the car, ready to operate the pump when an elderly man came out of the garage and on to the forecourt. Instead of having to fill the car myself, he filled it. While he was putting petrol into our car’s tank, I looked around and noticed that his small garage was filled with about five used cars, all with prices attached.

The most prominent car on sale was an aged Bentley, which the garage owner told me he had been driving for the past 15 years. The other cars in the small showroom-cum-garage included a vintage MG convertible; an old Jaguar sports car with a soft top; an Austin Seven complete with engine crank; and a very old looking Morris Minor. The owner, who had filled our car, allowed me to take photographs of his collection of old vehicles and appeared pleased when I told him that his garage was like a small motor car museum.

The Double-S is across the road from a small Victorian gothic chapel built with granite walls and a tiled roof. This is The Annunciation. It is the parish church of Breage with Godolphin and Ashton and is contained within the C of E diocese of Truro. The edifice was designed by the prolific church architect James Piers St Aubyn (1815-1895) and dedicated in 1884. The church is small but seen from outside, it is lacks architectural distinction.

We could have filled up at a superstore, where petrol prices are often not unreasonable, but I am glad that we patronised The Double S Garage, which must be amongst a diminishing number of fuelling places in England where the customer does not need to serve himself or herself. Also, it was fun finding the fascinating collection of vintage or almost vintage cars being stored close to the pumps. It is idiosyncratic experiences such as visiting this garage that help to make Cornwall a delightful place to visit.

June 30, 2021

A saint, a hermit on high, and a cousin

I HAVE OFTEN VISITED my cousin, Peter, who lives near Bodmin in Cornwall. On my way to see him, I have always noticed signs pointing to roads leading to Roche. It was this year, only on our most recent visit to the area, that we first visited the small village about 6 miles southwest of Bodmin. Roche, pronounced as in ‘poach’, and is French for ‘rock’, is known as ‘Tregarrek’ in the Cornish language, which means ‘homestead on the rock’, which is a suitable name for the place, as I will explain.

Hermitage at St Roche, Cornwall

Hermitage at St Roche, CornwallUnfortunately, the parish church was closed when we stopped in Roche. It is dedicated to St Gomonda, one of the many saints barely known outside Cornwall. Robert Meller, who is compiling a fascinating multi-volume, encyclopaedic account of Cornwall, wrote of Gomonda:

“Precisely nothing is known about this female-sounding saint and in reality, she might have been Saint Gonand, a male saint.”

Nothing is known about St Gonand. It is also possible that the church was dedicated to Bishop Conan, the first bishop of St Germans, appointed in the 10th century. The church itself has a Norman font (which we were unable to see) and a mediaeval tower (15th century). The rest of the church was rebuilt between 1820 and 1822 in a style typical of older churches in the area.

St Gomonda’s churchyard, which we entered by crossing over a stile made of granite slabs, contains a weathered Cornish cross, a primitive-looking monolith about six feet in height. The stone is covered with man-made indentations or carvings. One of these depicts a sword, which according to Meller, is an unusual image to be found on a Cornish cross. There have been standing stones, menhirs, such as the cross at St Gomonda, since before Christianity arrived in Cornwall. The crosses with Christian symbolism date from the 5th century onwards. It is therefore possible that the one we saw at Roche was pre-Christian with later Christian carvings, but here I am merely guessing.

About 420 yards southeast of the parish church, there is a ruined early 15th century, two-storied hermit’s chapel. Like many holy Hindu shrines in India and the monasteries in Greece’s Meteora district, the chapel perches high above the land around it. It can be seen 60 feet above its surroundings on the top of Roche Rock, whose presence inspired the naming of the village near it. Built in 1409 and dedicated to St Michael, the chapel used to be accessed by an iron ladder. At some stage, the cell beneath the chapel (on the upper floor) was occupied by a leper, expelled from his village because of his illness. He survived because every day, his daughter, Gundred, carried him water from a well about a mile and a half away. For her compassion and kindness, she was sanctified, becoming yet another of the saints of Cornwall.

Roche Rock and its chapel figure in various folk legends, including “Tristan and Isolde”. Meller wrote that when King Mark was chasing the lovers, Tristan and Isolde:

“… they took refuge in Roche Chapel to escape capture …To escape capture from the soldiers, Tristan jumped out of the chapel window – referred to as ‘Tristan’s Leap’”

Putting aside legends, the Roche Rock is an exceptional geological feature. Geologists consider it to be the finest example of quartz-tourmaline rock in Britain. It is composed of quartz and black tourmaline, which is a type of granite also known as ‘schorl’. Schorl is extremely hard and resistant to being worn away by the weather. Over the millions of years since this large lump of stone was formed, the surrounding terrain has been worn away, leaving the prominent rock that we see today.

I doubt that I would have thought twice about visiting the place had my cousin not lived nearby. I first met Peter in the early 1980s or late 1970s. Then, I got to know him and his family as friends. In the late 1990s, I began researching my family history, a process that included filling in gaps on family trees. A relative in New Zealand provided me with much information about a branch of my mother’s extended family. You might be able to imagine my surprise when I discovered from this information what Peter and I never knew before – that we are related; we have a common ancestor. We found out that apart from being friends, we are also members of the same family. Peter and I are doubly related because my mother’s parents were second cousins once removed. Peter and I are not only 4th cousins but also 5th cousins.

Our first visit to Roche proved interesting. Small as it is, Roche contains several things to see, which are some of the many features that help to make Cornwall attractive for visitors. Although one might not want to stay there, it is worth making a small detour from the main A30 road to explore the place briefly.

June 29, 2021

Packed with art in St Ives, Cornwall

THE TATE GALLERY has two branches in the picturesque fishing port of St Ives in Cornwall. The artworks displayed at Tate St Ives are contained in a building overlooking Porthmeor Beach, constructed between 1983 and 1993. It replaced a disused gasworks, but I feel that the gallery’s almost fascistic architecture neither does anything to enhance the town or to match the beauty of many of the items displayed within it. The other part of The Tate in St Ives is house and gardens of the sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975). A visit to her former home and its garden, filled with her sculptures, is a delightful experience.

Barbara Hepworth and her sculpture in the Penwith Gallery

Barbara Hepworth and her sculpture in the Penwith GalleryNot far from the Tate St Ives, there is another ‘must-see’ attraction for lovers of modern and contemporary art. This is the Penwith Gallery on Back Road East. Less visited than the two Tate institutions in St Ives, the Penwith is the home of the Penwith Society of Arts, one of whose founders was Barbara Hepworth. The gallery contains one of the loveliest Hepworth sculptures that I have seen to date. Maybe I like it because it recalls the works of the Romanian born sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), a sculptor whose works are much to my taste. To be frank, I am not a great lover of Hepworth’s sculpture and this piece in the Penwith is less typical of what I do not like about her work.

Returning to the gallery itself, its website reveals (https://penwithgallery.com/):

“The society was founded in 1949 by Barbara Hepworth,Ben Nicholson, Peter Lanyon, Bernard Leach, Sven Berlin and Wilhelmina Barns– Graham, amongst others. Later members have included Patrick Heron, Terry Frost and Henry Moore (honorary member). This association with so many progressive and influential artists has given the Penwith Society a unique place in British art history.

Today the society continues to play a central role in the thriving and vibrant St. Ives art community, exhibiting contemporary art from Cornwall and beyond.”

The gallery is housed in a former pilchard packing factory. Its ceiling is supported with roughly hewn granite pillars, painted white. Part of the ceiling is glass-covered, allowing natural light into the largest of the three main display areas. The rest of the ceiling does not transmit light.

The gallery displays an ever-changing collection of artworks, which are on sale. Created by members of the Society or artists, who have worked in the Society’s studios, they include sculptures, prints, paintings, and ceramics. Some of the works are figurative and many of them are abstract. Some are halfway between the two extremes. I have enjoyed abstract art since my childhood. This is probably because my mother, who was a sculptor who enjoyed creating abstract pieces. The lovely Hepworth piece that stands next to a fine photograph of its sculptor, and several other works, form part of the Penwith’s permanent collection. A small range of books and cards are available for visitors to purchase.

Every time I visit the Penwith, I enjoy the gallery’s spaces and the works displayed within them. Instead of being packed with pilchards, as it was in the past, and other tourists, as are the two Tate establishments, the Penwith is comfortably packed with pleasing works of art, which you can take home if you can afford them, and some of them are not excessively costly.