Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 158

June 18, 2021

Dandelion

June 17, 2021

Ideas and appearance

EVERY YEAR SINCE 2000 (except 2020), the Serpentine Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens has commissioned a temporary pavilion to be constructed next to it. A website (www.inexhibit.com/case-studies/serpen...) explains:

“The pavilions, which last for three months and should be realized with a limited budget, are located in the heart of the Kensington Gardens and are intended to provide a multi-purpose social space where people gather and interact with contemporary art, music, dance and film events.”

The architects chosen to design these temporary structures have not had any of their buildings erected in London prior to their pavilions. Some of the architects involved over the years included Zaha Hadid, Smiljan Radić, Sou Fujimoto, Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei, Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, Frank Gehry, Olafur Eliasson & Kjetil Thorsen, Álvaro Siza, and Eduardo Souto de Moura with Cecil Balmond, and Oscar Niemeyer.

With a very few exceptions, I have liked the pavilions and admired their often visually intriguing, original designs. My favourites were the 2007 pavilion by Olafur Eliasson & Kjetil Thorsen; 2009 by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa; 2013 by Sou Fujimoto; and 2016 by Bjarke Ingels.

This year, the pavilion was designed by an architectural practice, Counterspace, based in Johannesburg (South Africa) and led by Sumayya Vally, who is the youngest architect to have become involved in the Serpentine pavilion project. According to the Serpentine’s website (www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/serpentine-pavilion-2021-designed-by-counterspace/) the 2021 pavilion is:

“… based on past and present places of meeting, organising and belonging across several London neighbourhoods significant to diasporic and cross-cultural communities, including Brixton, Hoxton, Tower Hamlets, Edgware Road, Barking and Dagenham and Peckham, among others. Responding to the historical erasure and scarcity of informal community spaces across the city, the Pavilion references and pays homage to existing and erased places that have held communities over time and continue to do so today.”

Well, maybe this was the designers’ aim, but it does not convey that concept to me. This circular, building coloured black and white, immediately conjured up in my mind images of often disused municipal structures such as bandstands and public conveniences that might have been constructed on provincial British or even South African seafronts in the 1930s to 1950s. It might have been conceived with high-minded ideas in the architects’ heads, but I felt that the structure is lacking in visual interest both in detail and in its entirety. Compared with many of the previous pavilions erected on its site, this is one of the dullest I have seen. It is a shame that the pavilion’s creators did not put more effort into its appearance than into the message(s) it is supposed to convey. To my taste, it is a disappointment but do not let me put you off: go and see it for yourself.

June 16, 2021

Many thanks!

I have just noticed that so far 900 people are following my blogs.

I wish to express my gratitude to you all for taking an appreciative interest in what I write.

Thank you very much and please do spread the good word about my website.

A peculiar post office

WHEN I WORKED AT MAIDENHEAD, I used to travel there by train from London Paddington. Many of the trains terminated at a station called Bedwyn, which serves Great Bedwyn. I visited this small town on the Kennet and Avon Canal for the first time only recently. While driving through the place, I noticed a building covered with gravestones and other ornamental carving. My curiosity was aroused.

The name ‘Bedwyn’ might have been derived from ‘Biedanheafde’, an Old English word meaning ‘head of the Bieda’, which referred to a stream in the area. In 675 AD, “The Anglo Saxon Chronicle” recorded the battle of ‘Bedanheafeford’ between Aescwine of Wessex and King Wulfhere of Mercia, which is supposed to have been fought near the present Great Bedwyn. The will of King Alfred the Great (c848-899) makes reference to Bedwyn. In short, Bedwyn has been a recognizable settlement for a long time.

Bedwyn’s combined post office and village shop can be found in a long, rectangular brick building on Church Street. The wall at the east end of the edifice carries a depiction of the Last Supper and above it, God on a throne, surrounded by saints and angels. These sculptural panels are in white and blue and somewhat resemble the kind of things produced by the Florentine sculptor Luca della Robia (1400-1482). Three gravestones are attached to the west facing end of the post office. A wooden gate next to this end of the building is labelled ‘Mason’s yard’. The front of the building, facing the street, is adorned with carved funerary monuments including gravestones, some of which bear humorous inscriptions.

The shop is attached to a house with a front door framed by a gothic revival porch. A carved panel in the porch reads: “Lloyd. Mason.” I asked some of the customers queuing up to enter the shop/post office if they knew anything about the curious decoration of the building. I was told that the place had once been the workshop of a stone mason who specialised in funerary items. My informant said that most of the carvings attached to the building were test pieces made by the stonemason’s apprentices; rejected or uncollected items; and offcuts.

Benjamin Lloyd (1765-1839), who died in Bedwyn, started his stonemasonry business in 1790 (www.mikehigginbottominterestingtimes.co.uk/?p=2825). He was responsible for some of the work done during the construction of the Kennet and Avon Canal, which began before he was born and was eventually completed in 1810. The company still exists. Now, it is run by John Lloyd, the seventh generation of the family to maintain the business (www.johnlloydofbedwyn.com/about-us). However, his premises have moved away from Bedwyn’s post office.

Benjamin Lloyd is buried alongside his wife Mary (1764-1827) in St Mary’s Church Burial Ground in Great Bedwyn. I do not know, but I would like to imagine, that their gravestone was made in the company Benjamin created.

June 15, 2021

The humble iris

See and admire the elaborate structure of this beautiful petal of an iris.

And reflect on its intricate complexity as you consider the brevity of the life of a flower.

Nature did not design this merely to please our eyes but to serve a greater purpose: the survival of a species.

June 14, 2021

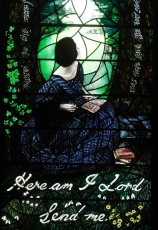

Lady with the lamp

ROMSEY IN HAMPSHIRE is a delightful small town with a spectacular parish church, Romsey Abbey, with many Norman and gothic architectural features. The edifice that stands today was originally part of a Benedictine nunnery and dates to the 10th century, but much of its structure is a bit younger. It rivals some of the best churches of this era that we have seen during travels in France. That it still stands today, is a testament to the good sense of former citizens of the town.

During Henry VIII’s Dissolution of The Monasteries in the 16th century, much of the nunnery was demolished. However, the establishment’s church was not solely for the use of the monastic order but also served as a parish church for the townsfolk. As Henry VIII was not against religion per se, and the need for a parish church was recognised, the townsfolk were offered the church for sale. In 1544, the town managed to collect the £100 needed to purchase the church and what remained of the abbey from The Crown. Thus, this precious example of church architecture was saved from the miserable fate that befell many other abbey churches all over England. However, what you see today was heavily restored in the 19th century, but this does not detract from its original glory.

The town of Romsey is 3.4 miles northeast of East Wellow, the burial place of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), the social reformer and statistician as well as a founder of modern nursing. I had no idea that Florence was famous in the field of statistics. Her biographer Cecil Woodham Smith wrote:

“In 1859 each hospital followed its own method of naming and classifying diseases. Miss Nightingale embarked on a campaign for uniform hospital statistics … which would ‘enable us to ascertain the relevant mortality of different hospitals, as well as different diseases and injuries at the same and at different ages, the relative frequency of different diseases and injuries among the classes which enter hospitals in different countries, and in different districts of the same countries.’”

In 1858, she was elected a member of the recently formed Statistical Society. So, there was much more to Florence than the commonly held image of ‘the lady with the lamp’ during the Crimean War.

Florence was christened with the name of the Italian city, where she was born. Part of her childhood was spent at the family home of Embley Park, which is 1.8 miles west of Romsey Abbey church and close to East Wellow. Now a school, it remained her home from 1825 until her death.

Broadlands, which was built on lands once owned by the nuns of Romsey Abbey, is a Georgian house on the southern edge of Romsey. It was home to Lord Palmerston (1784-1865), who was Prime Minister in 1856 when the Crimean War came to an end. Broadlands was Palmerston’s country estate. It is maybe coincidental that both Palmerston and Nightingale were associated with both Romsey and the Crimean War.

Palmerston is celebrated in Romsey by a statue standing in front of the former Corn Exchange. Florence has a more discreet memorial in the town. It is a stained-glass window within the Abbey church. Placed in the church in 2020, it was formally dedicated in May 2020. It depicts a young lady seated by a tree, her face turned away from the onlooker. Created by Sophie Hacker, the image depicts Florence seated on bench beside a tree in Embley Park. The tree in the window, a cedar, still stands in Embley Park’s grounds. The image is supposed to recall the moment when, as a young girl, she received her calling. Woodham Smith wrote:

“Her experience was similar to that which came to Joan of Arc. In a private note she wrote: ‘On February 7th, 1837, God spoke to me and called me to His service’”.

The window includes the following words above her head:

“Lo, it is I.”

And beneath her:

“Here am I Lord. Send me.”

There are a few other words on the window, some in English and others in Italian.

A visit to Romsey Abbey church is highly recommendable. We thought that we had visited it many years before 2021 and arrived expecting to see an abbey in ruins. We were delightfully surprised to realise that we had mistaken Romsey with some other place, whose name we have forgotten, and instead we had discovered a church that was new to us and unexpectedly wonderful both architecturally and otherwise. Anyone visiting nearby Winchester with its fine cathedral should save some time to come to see the magnificent ecclesiastical edifice in Romsey.

June 13, 2021

Dragonfly

June 12, 2021

From Egypt to Dorset

CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE IS a familiar landmark in London. It was originally erected at Heliopolis in Ancient Egypt in about 1450 BC and brought to London in about 1877. Less well-known is another hieroglyph covered obelisk in the gardens of Kingston Lacy near Wimborne in Dorset.

The pink granite obelisk at Kingston Lacy arrived in the grounds of this rich family’s dwelling in about 1827. Like Cleopatra’s Needle, this monument is inscribed with hieroglyphics. Because there is a mixture of Greek words and hieroglyphics, the obelisk, discovered on an island in the River Nile, became important in the early attempts to decipher the Ancient Egyptian writing.

In Banke’s collection of Egyptian artefacts at Kingston Lacy

In Banke’s collection of Egyptian artefacts at Kingston LacyKingston Lacy has been owned by successive generations of the Bankes family since the 1660s, when John Bankes (1589-1644) took possession of the estate and built the present grand house. One of his descendants, William John Bankes (1786-1855), who met Lord Byron when they were both studying at Cambridge University, first travelled in Spain and collected a vast number of Spanish paintings, many of which are hanging within Kingston Lacy House. Later, during the early part of the 19th century, William travelled extensively in the Middle East and along The Nile. During his travels, he collected many valuable Ancient Egyptian artefacts, some of which are beautifully displayed in a former billiards room within Kingston Lacy House.

The obelisk was found by Bankes at Philae in Upper Egypt in 1815. According to Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philae_obelisk), the inscriptions on the object:

“… record a petition by the Egyptian priests at Philae and the favourable response by Ptolemy VIII Euergetes and queens Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III, who reigned together from 144-132 BC and again from 126-116 BC. The priests sought financial aid to help them deal with the large numbers of pilgrims visiting their sanctuary and the king and queens granted the sanctuary a tax exemption.”

Both the Greek and the Egyptian inscriptions deal with the same topic but are not direct translations of each other.

June 11, 2021

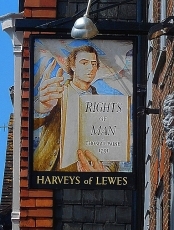

Rights of man

BULL HOUSE STANDS on the High Street immediately beneath the remain of the castle that dominates the Sussex town of Lewes near Brighton. Its neighbour is an older, half-timbered edifice that now houses The Fifteenth Century Bookshop, a supplier of second-hand books, which was unfortunately closed when we passed it on a Sunday morning.

In the year 1768, the owner of Bull House, a tobacconist named Samuel Ollive, and his wife Esther, took in a lodger, who had arrived in the town. This man was an excise officer aged about 31. His name was Thomas (‘Tom’) Paine (1737-1809). 1n 1771, Paine, already a widower, married Elizabeth Ollive, daughter of Samuel and Esther. At of that time, he became involved in the Ollive’s tobacco business as well as the administrative affairs of the town of Lewes. A year later, as part of a campaign to improve the remuneration of excise officers, he published a pamphlet. “The Case of the Officers of Excise”. Tom enjoyed lively discussions and debates at the town’s ‘Headstrong Club’, which met at the White Hart Inn on the High Street. This hostelry can still be seen today.

The year 1774 found Tom in trouble. He had been accused of being absent without permission from his position as excise officer. Also, his marriage failed, and he separated from his wife Elizabeth. To avoid a spell in a debtors’ prison, he sold all his possessions. He left Lewes and went to London, where he was introduced to the revolutionary Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), who recommended that Tom should emigrate to North America. Tom set sail from England and arrived in Philadelphia in November 1774.

The pamphlet that Paine wrote in Lewes was followed by many more published writings. Amongst these is his best known, “The Rights of Man”, published in 1791, in London, England, where Tom had returned in 1787. This work is described in a guidebook to Lewes as “…the bible of English-speaking radicals.” Whether Tom ever returned to Lewes after his first excursion to what is now the USA, I do not know. If it ever occurred, it is not mentioned in my guidebook, and I have not found any reference to it.

June 10, 2021

On the temple steps

THE DOMED IONIC temple in the gardens of Chiswick House in west London was built in the early 18th century. It appears in a painting executed in 1729. This circular building is faced by an obelisk that stands in the centre of a circular pool. Today, we walked past these neoclassical garden features when we noticed a lady in a flowing white dress posing on the steps of the temple. Facing her across the circular pond were cameramen and their assistants, some holding large reflector screens. They were either carrying out a photo-shoot or making a film. Every now and then, a man holding a smoke gun ran past the temple creating an illusion that the temple was bathed in mist. Here is a photo I took whilst this activity was in progress.