Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 119

March 25, 2013

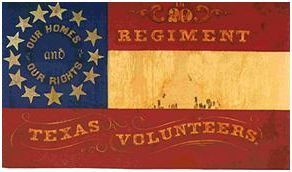

Secessionism 101: Feds maintain the Civil War didn’t end in Texas until mid-1866

I didn't realize that the U.S. government held that the

Civil War didn't end in Texas until sometime in 1866. In a document issued in

April of that year, President Andrew Johnson omitted Texas from a list of

pacified states, but he included it in a proclamation issued that August.

I learned this in an article by Ida

Tarbell titled "Disbanding

of the Confederate Army" that appeared in McClure's magazine in 1901. My issue

just arrived.

The sunshine general: JCS Chairman Dempsey reviews the world situation

By Eve

Hunter

Best Defense guest columnist

General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff, in an appearance at the Center for Strategic and

International Studies this past Monday, quoted F. Scott Fitzgerald's definition

of a first-rate intelligence as being able to hold two competing and opposing

ideas in your mind at the same time. That is precisely the predicament he put

his audience in.

Gen. Dempsey approached the current

geopolitical situation with a jovial attitude. He compared the U.S. position in

the world with the TV character "Mayhem," of Allstate Insurance (and 30 Rock) fame. His face was aglow with

patriotism, even while confronting questions concerning "the West's failure in

Syria." Hedging his bets, he spoke positively of the

Iraq War, saying that Iraq is now a "partner, not [an] adversary."

Despite the general's optimism,

however, he was very clear in the fact that Congress is inhibiting America's

potential to be a "global leader" and a "reliable partner." Dempsey spoke of a

prospective shift in defense strategy that would include

eliminating unnecessary weapons and recognizing, with funds, that diplomacy is

the key to global security.

The most engaging part of his speech

was his willingness to admit uncertainty. On a macro-level Dempsey was

ebulliently confident, but on country-specific questions, he seemed just as flummoxed

as the rest of us. For example, our understanding of the Syrian opposition is

more opaque than it was six months ago. On Iran, the one question he

would ask Ayatollah Khomeini is why he is doing what he is doing. Dempsey's

relationship with his newly appointed Chinese counterpart is only in the

beginning stages; implications for defense remain murky.

Many may see a lack of decisiveness as

a weakness, but at this inflection point in history I am happy to have a man

like Dempsey leading our Joint Chiefs. He is aware of the complexities of

today's world, as made clear by an alliterative reference to bits and bytes

being as dangerous as bullets and bombs. At the same time he is painstakingly

deliberate, which, at the 10 year anniversary of the

invasion of Iraq, is a welcome change.

March 22, 2013

More things I didn’t know: The Italians bombed England in World War II?

It is mentioned in the diary of John Colville,

one of Churchill's aides during the war. Churchill was so mad he said he would

make sure Rome was bombed.

Colville is a snob and a prig, but his diary contains many

illuminating passages about Churchill, and also some inadvertently good

insights into the British mentality during the war. Among other things, they

have no idea of how much ground they have lost technologically, which slammed

their economy in the following decades.

Another interesting moment came in February 1944, when

Churchill mistakenly had the songwriter

Irving Berlin to dinner, believing he had invited the philosopher and diplomat Isaiah Berlin. He kept pestering poor Irving with questions about his

thinking about when the war might end. The great songwriter, no slouch himself,

correctly predicted that FDR would run for a fourth term and win.

Also, on New Year's Day 1953, Churchill predicted that communism

in Eastern Europe would end before the century did. Well played, sir.

Air Force colonel relieved for being fat

Jeff Schogol, one of the more

historically knowledgeable military reporters out there, writes about an interesting case of holding people to standards.

Yet I cannot help but think of many

plump generals I have seen -- are they going to be relieved also? Or are GOs

exempt? Different weights for different rates?

Rebecca’s War Dog of the Week: 'NCIS' episode highlights military dogs in Afghanistan

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

Tuesday's episode of NCIS,

titled "Seek," not only features a military working dog and his handler but

revolves around them. Without giving too much away for anyone who missed the

show, the episode

begins with this Marine handler and his dog, a black lab named Dex, searching

a village lane in Afghanistan. Moments after a harrowing encounter with an IED,

the handler is shot and killed by a sniper. Shortly after this, the NCIS cast of characters is called in to

track down the handler's killer with Dex lending a helping paw.

Co-executive producer, Scott Williams, blogged about

the making of this episode, writing that inspiration for the storyline came

last year after the photo

of Hawkeye "laying faithfully beside the

flag-draped casket of his late master, Navy SEAL hero Jon Tomlinson," went

viral.

I've never watched NCIS

before and, as you might expect with a storyline like this, there's a bit of

creative license taken with its portrayal of the handler-canine combat-zone

experience, elements of which are plied for dramatic effect. But aside from some

overwrought canine wordplay, I was surprised by how few head-shaking moments

there were; the show's producers appear to have been very committed to an

accurate representation of an MWD's role in wartime -- from the jargon handlers

use to expository dialogue with a bit of war-dog history. Even the episode's

title "Seek," referring to the command a handler gives his dog when on an

explosive-seeking patrol, felt like an authentic tip of the hat to military dog

teams.

There's good reason for this accuracy, as the television

network hired a few MWD experts to work behind the scenes while filming,

including our friend Mike Dowling, former Marine handler

and author.

Dowling, who worked on the show as a technical advisor, says he enjoyed consulting

with NCIS writers and actors. "I really

appreciated how they

wanted to make sure they were honoring the military dog community properly," he

says. "They were very open to listening and learning about the

heroic work military dog teams do." Dowling

also mentioned that Dexter, the dog actor playing "MWD

Dex," was "simply brilliant." I agree, for while you'd be hard pressed to find

a dog who didn't pull heartstrings in this kind of story, Dexter alone makes

the show worth watching.

If you missed it, you can watch the episode

online (though fair warning, the amount of commercial interruption alone is

prohibitive). The

moment of the episode that really struck a chord with me came during one fairly

unremarkable scene where Mark Harmon's character, Special Agent Gibbs,

interviews a military contractor who witnessed the handler being shot. When Gibbs

wants to know what dog team's assignment was, the man replies, "[To] save our lives."

March 21, 2013

The FP transcript (VIII): Can we buy a fully capable force as defense budgets fall?

[Here are Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII.]

Crist: One of the

things as a federal employee who works on current Middle East issues, and

having studied pretty extensively for a project on the Joint Staff the lead-up

to decisions on Iraq, the thing that has struck me is that the lessons learned

among policymakers from Iraq is there was a lot of thought given -- which was

not the case in 2002 and 2003 -- given to second- and third- order effects of

American action and what are the ramifications for this that we don't

anticipate. Whether that can be sustained over the next generation or just each

generation learns its lesson, institutionalizes it and [inaudible].

Dubik: The

lesson-learned process and what people learn from our 10-year experience is

important. There is a reasoned way to think through using force, there is a

useful process in increasing the probability that you'll get it more right than

wrong -- not that you'll ever get it absolutely right.

I fear that we are throwing out counterinsurgency because we

are never doing that again. But we already did that once: It was post-Vietnam.

Counterinsurgency is not a strategy; it's a way to deal with an insurgency, and

if you face it again, it gives you a relatively decent structure to think

through these things. It certainly shouldn't be a national strategy. It was

never designed to do that.

Ricks: Another

person who could not attend today, Kyle Teamey, who

some of you may know, a terrifically smart young man, sent in this question:

"Is there anyone at this table who thinks we will not do counterinsurgency

again?"

For the record, I want to note that everybody agrees we will

do counterinsurgency again.

Mudd: But we went

in to do counterterrorism, and now all we talk about is counterinsurgency. So

success on Sept. 12 would have been, "Is there going to be an attack

against the United States?" and by 2003 that answer was no. And now we say

success is: Should we have a third election? And my view would be, if the

Taliban wins, I don't care as long as we have a residual capability to

eliminate the target we went in to get.

I hate counterinsurgency, because it wasn't our threat. Just

a quick asterisk: In parallel with these major wars we had intervention in

places like Somalia and Yemen. There's been no tactical conversation here, and

I think appropriately -- but especially with the new tactical capability--

we've been able to say, "Man, we are giving the president in some cases better

options, but in some cases much tougher?" You want to go into Mali? You want to

go against Boko Haram? I want to know why we are not talking about armed drones

against cartels, which were a much

bigger threat to this country than terrorism ever was or ever will be. But it

is interesting that parallel subwars or campaigns is part of this war and what

they mean about American intervention in the future that leads not only to

things like increasing the capacity of the partner but also unilateral use of

force against a target without ever having to put a boot on the ground fast.

Ricks: What do

they tell you?

Mudd: That tells

me that we are going to be into it because we are going to say there's a way to

get out of this without putting big green on the ground.

Flournoy: I think

that there probably will be some point in the future where we decide to help a

government deal with its problem of insurgency, and that's the thing: It's not

our insurgency. The question is: Can we come to some consensus on what's the

right model? Is there a single right model for that, or is it really entirely

case by case? To me, after the experience of the last decade or more, the El

Salvador model looks a lot more attractive than the conventional occupation

model of Iraq and Afghanistan, but is that just being falsely wedded to

something? Can we generalize from these different experiences to say there is

one approach that either is generally more effective or, from our own political

culture, generally more acceptable and sustainable to the American people?

Ricks: I'm going

to try and answer your question. I would say, yes, clearly: Light footprint,

minimal American boots on the ground, leading from behind, helping host nation

abilities, or even helping third parties like we've been helping the Colombians

help the Mexicans on the drug war. These are the things that work; these are

the things also that go to the issue of sustainability. I once was talking to Elliott

Abrams, and I said I thought secretly more Americans had been killed in El

Salvador than were killed in the 1991 Gulf War. He said, "Yeah, but I won

my war."

Alford: You also

have to design the force to support your strategy. You got to start thinking

about the force.

Ricks: We have a

force that's tactically magnificent, but is it relevant, Colonel Alford?

Alford: No, I

don't think we are organized the way we should be right now for the future.

Ricks: How should

we be better organized?

Alford: Well, I

mean all the things you just talked about were what the U.S. Marines do from

amphibious ships. We are balanced, we are flexible, we are adaptable, and we

are forward deployed. We can go in and be out and not have to put a footprint

on the ground for any significant period of time. And that's what we want.

I mean, I love the U.S. Army -- we have the best U.S. Army

in the world, but in Kosovo when you take in 24 helicopters and it takes 6,000

troops to support those 24 helicopters, that's not the future.

Ricks: I need to

go now to the Army generals who have been shaking their heads.

Dubik: We have a

great Marine Corps for a reason, and I'm glad we have it. But we have a great

Air Force, and Navy, and Army for a reason that we need also.

But I play golf with 13 clubs. And I like to solve problems

with more than one conceptual framework. So I'm not at all satisfied with a

conclusion of our last 10 years of war that "quote, unquote" this

approach works. I think that that would be a dangerous way to come out of this

war. For me, the lesson learned is come to a war with more than one conceptual

framework. Because every war, while it may have some common elements, every

war, as Clausewitz says, is a chameleon, admits to its own solution, and you

have to think through that solution. So the light-footprint approach that you

talked about works in many, many circumstances, but there are an equal number

that it won't.

Ricks: So be

adaptive is what you're saying?

Dubik:

Intellectually adaptive.

Ricks: I've been

reading another history of World War II recently which Churchill keeps on

saying in ‘39, ‘40, ‘41 that this will not be a force-on-force war.

Dubik: [Laughs.] Yeah, well it ended up being

that way.

And that gets to my comment about adaptability. It's not

just intellectual adaptability but force adaptability. If you predict one

future and you optimize your force for that future, you're either a hero or a

goat. You're a hero if the future unfolds as you predict. You're a goat because

you've got the country's reputation on something that now is not relevant. So

in our force-structure decisions coming up necessarily as a result of the

position we are in strategically and fiscally, maintaining as many options as

we possibly can is an important way forward in an uncertain environment. It's

organizationally important to have alternatives.

Ricks: Is it

possible to maintain options in an era when I'm guessing defense budgets are

going to go down 30 percent in the next few years?

Dubik: My own

answer is yes. The number of options may be reduced, but you can still retain a

good number of options if you are willing to break some rice bowls in terms of

current organizational structures, active, guard, reserve in each of the

components.

Mudd: A sand

wedge is what you're saying.

Dubik: Yeah, I

use a sand wedge.

Alford: One of

the four words I used there was adaptable. You've got to have a number of tools

in the box to cross the threat that we are going to face, which I believe is

going to be a more hybrid, irregular, not a toe-to-toe threat. That's going to

be the most prevalent, I believe.

Ricks: And the

other head-shaking general?

Fastabend: I'd

like to make two comments. Jim [Dubik] talked adequately about the need to have

13 clubs in the bag. I can't restrain myself from saying this now that I'm

retired: You can't help but love the Marine Corps. They are simultaneously one

of the greatest and most insecure institutions that I've ever encountered in my

life.

(More to come, as the Army-Marine smackdown continues)

Military resilience, suicide, and post-traumatic stress: What's behind it all?

By Dr. Frank J. Tortorello, Jr. and Dr. William

M. Marcellino

Best Defense guest respondents

What's causing rises and falls in suicide, PTSD, and other

socially negative outcomes for U.S. service members? We recently completed a

research project in the Marine Corps sponsored by the Training and Education

Command and the Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning aimed at

understanding how Marines understand stress and resilience. The results we

reported suggest that the issue is not so much medical as social, cultural, and

personal. Typical explanations of stress from a medical perspective suggest

broken biology (defective genes or an IED blast) or compromised psychology (a

psychological disposition or traumatic event). But this study found instead

crises of meaning: "How can I be a good Marine and be a good parent?"

or "How can I be a good Marine if I have let another Marine die?" This

is a single study, and we didn't talk to every Marine. But we think this

central insight has broad explanatory power for some problems Marines and other

servicemembers face.

When we asked, Marines in the study told us in great detail

what stress and distress are for them, and how they deal (or don't) with it. At

one end of the scale are Marines equipped to do resilience work -- actively

getting themselves back to a good state after distress. They can, for example,

forgive themselves for battlefield errors. At the other end are ones who do not

know how to (or choose not to) forgive themselves for real or imagined

failures, standing in judgment of themselves. And in the middle are those

Marines who are making it, but nagged by doubts about their worth or standing.

As these Marines told it, stress is variable and contextual,

and what is debilitating for one Marine isn't noteworthy for another. According

to them, there's nothing inherently traumatizing about seeing or inflicting

death; instead, these -- like all human action -- present an interpretive

choice: "I did what I had to do," vs. "I'm a murderer." Which

meaning is made depends on the Marine and their context.

All of this hinges on a fundamental question about the role

of our biology: Is it an important resource for making meaning, or is it a

mechanism that causes us to make certain meanings? The answer dictates what

legitimately constitutes data, and methods of data collection and analysis in

research. Typically we see researchers who work from a medical perspective,

even when claiming not to reduce humans to their biology, writing as if biology

causes certain social meanings. Only with this assumption does it make sense to

ignore whole persons in favor of parts of their biology or psychology.

On what scientific basis, we ask, are quantifiable

bio-phenomena substituted for what a Marine says in explaining his or her

stress? How are urinary free-cortisol levels more relevant for explaining and

understanding PTSD than a Marine's explanation that he's accountable for

another's death, and so doesn't deserve to live? That those with PTSD might

have altered catecholamine and cortisol levels is not in question, but rather

why researchers accord this primary focus or decisive weight in explaining what

otherwise appear to be issues of personal meaning.

Just as important are this question's implications for

interventions. If military members are only biomechanical creatures, then

currently funded research in areas like anti-depressant nasal sprays or omega-3

fatty acid levels, and proposed funding for research in stellate ganglion

blocks, are all good investments of public tax dollars. If instead military

members are whole persons living in socio-cultural contexts that actively try to

make sense of their lives, then we are better off researching how to train,

equip, and prepare them for likely challenges to their values and worth, as

they understand them. Our research tells us that there is a lot of preparation

already going on: Parents, coaches, good mentors and peers all help Marines

come up with strategies to avoid becoming dis-stressed, and ways to re-balance

if they do. Resilient Marines can articulate where they learned such

strategies, and how they employ them. But all this is ad hoc and private. The

services do a good job consistently and publically preparing military members

for combat and operational stress, but members are more than simply their

duties. The services could do just as much to prepare and support them in the

wider scope of living.

Dr. Frank J.

Tortorello, Jr. is a contracted socio-cultural anthropologist who develops and

researches foundational issues that impact the Marine Corps's global deployment

and war fighting capabilities. Dr. Tortorello focuses on Marine Corps culture

and how the Corps replicates its values through training and everyday work. His

research examines how Marine Corps culture both enhances and detracts from its

ability to deploy globally across the spectrum of missions from conventional

warfare to humanitarian relief. He has a special interest in resilience training,

defined as managing value conflicts and ethics in warfare, and in the

assessment of the impact of cultural training on Marine Corps operations.

Dr. William M.

Marcellino is a contracted researcher

in sociolinguistics and discourse analysis, who provides research support for

the USMC's Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning. His research focus

is in resilience and cohesion issues, and he is a former U.S. Marine Corps

officer and enlisted. The views presented in this work are the authors and do

not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, the U.S.

Government, or ProSol, LLC.

To fix critical thinking within PME, start at the ground floor with the basic stuff

By

Nicholas Murray

Best

Defense department of restoring standards to PME

The Army

has a critical thinking problem. To fix it, most focus on the need to change

the culture of the organization and the curricula of the staff schools and

higher. Fixing this will help, but only from the mid-career point onward. If we

really want to change the way the officer corps thinks, we need to start from

the ground up. That is, if we are truly going to fix Professional Military

Education, we must begin with a potential officer's undergraduate education.

Having

recently written an article for the Small Wars Journal examining Professional Military Education

through the lens of history, I was struck by the number of other articles

dealing with the general subject area. Almost all of them, however, including

mine, were focused on the staff officer schools or higher. This got me

thinking.

Perhaps

the problem starts much earlier in our system of commissioning. Here at the

CGSC I see a number of perfectly capable and bright officers who lack fairly

basic knowledge of their own history. Additionally, I've noticed that many of

them have never heard of the Treaty of Westphalia, and some have only the

vaguest awareness of international politics. Lacking such a foundation means

that they often flounder in classes where such issues are discussed, and I have

read many complaints about how this affects their ability to understand the

broader context of their role around the world. Additionally, the lack of

educational breadth means it is more difficult for them to grasp how things fit

together. Both Max Boot's and Harun Dogo's recent guest posts address

some of these issues and look at some of the consequent problems; they also

gave me food for thought.

What,

then, can we do to address some of these issues before officers reach the

middle stage of their career? An email from a cadet at the USMA pushed me

further in contemplating an answer (in it he reminded me of a guest post he wrote for Best Defense outlining some thoughts on

his experience). I thus came to the question: Why not do something more radical

than simply tweak what we do at the staff schools and above? Why not start from

the ground up? If all officers in the U.S. Army had to take courses in U.S.

history as a requirement of their being commissioned -- along with one or two

classes in Western civilization (or indeed world civilization), geography, and

international relations -- we might go some way to providing the background of

knowledge that many will need for much of their career. Being an immigrant

myself, I think it is a good idea, especially when considering the number of

serving soldiers who were born overseas. These classes would also facilitate

the broadening of knowledge that is so essential to effective critical

thinking. Of course, to become an officer a candidate needs to have completed a

four-year college degree. That surely solves the problem, right? Well, maybe

not, but it does suggest a solution.

With

that in mind I looked at the ROTC and OCS websites for guidance as to which of

the above classes are required as a part of the program. Disappointingly, these

courses were nowhere mentioned, at least, not that I could find. Furthermore,

simply requiring a four-year degree does not guarantee that an incoming officer

has taken even one of these classes let alone all of them -- it really depends

upon which school they attended and what that particular school's academic

requirements for a degree were. This is important because a solid base in these

subjects would provide much needed context for classes discussing strategy -- which

they will need later in their careers. It would also provide a greater number

of people who know something about the next piece of ground over which we have

to fight. That would be no bad thing. In its defense, the Army does require

that potential officers take a course in American military history, but that is

largely driven by the learning of facts (no bad thing) without the broader

analysis and context of what those facts mean (not a good thing). Thus, it does

not really address the central issue.

We need

to change the way we educate officers before they start their careers. This is

a solution to the Army's critical thinking problem. Additionally, fixing it

this way would at least mean that when officers show up for their education at

the staff schools and above they already have the grounding necessary for them

to focus on the essential. That is, preparing themselves intellectually for the

next ten years. That is, after all, our mission.

Dr.

Nicholas Murray is an associate professor in the Department of Military History

at the U.S. Army Command and Staff College. His book The Rocky Road to the

Great War (Potomac

Books) is due out this year, along with an edited book titled Pacification:

The Lesser Known French Campaigns (CSI). He recently published "Officer Education: What Lessons Does the French Defeat in

1871 Have for the US Army Today?" in the Small Wars

Journal. His views are his own. They are

not yours.

March 20, 2013

The FP transcript (VII): How our experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq shaped our approaches to Libya and Syria

[Here are Parts I, II, III, IV, V, and VI]

Ricks: Michèle,

you looked like you were about to say something.

Flournoy: I think

that this discussion is about the alignment of objectives. Are they

consistently aligned with our interests? And is the level of cost bearable and

appropriate, given the nature of our interests?

I saw that sort of insight applied to subsequent cases. I

think the experience of Iraq -- the inherited operations of both Iraq and

Afghanistan -- caused us to have a very fundamental strategic discussion about

Libya, for example, and why we weren't going to put boots on the ground, invade

the country, own it, et cetera. People have said, you know-- it's the

caricature of leading from behind, and that this is some terrible mistake for

the U.S.

What it was, was really circumscribing our involvement to

match what were very limited interests, to say we are going to play a

leadership role that enables others who have more vital interests to come in

and be effective. But we are not going to be out in front; we are not going to

own this problem; we are not going to rebuild Libya.

I think that the experience of Iraq and Afghanistan --

working through how do you get operations back onto a track where your

interests and your actions are aligned -- also informed things like Libya, like

Syria,

and so forth. You can argue whether or not that we made the calculation right,

whether we got it right or not. But I'm just saying that the conversation --

the fundamentals conversation -- did happen in subsequent cases because of, I

think, the experience in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

Ricks: Would you

say that President Obama -- to put you on spot -- is good at having that sort

of conversation?

Flournoy: In my

experience he is. If the staff doesn't -- if the process doesn't serve it up to

him -- he's usually pretty good at saying you're not asking the right question,

the right question is "x."

Brimley: I mean

just as a two-finger on that. That was my first month at the White House when

that happened. And it was an amazing process to watch almost from start to

finish as a case study in how a president considers the use of force.

Ricks: You're

talking about Libya?

Brimley: Yes.

When you read the history it seemed to me that with the decision to invade

Iraq, there might not have been a formal National Security Council meeting

where the benefits were voiced in open session in a proper process. But [on

Libya] the president held at least three or four full National Security Council

meetings and dozens of deputies and principals meetings to weigh that issue.

Ricks: And was

the question why front and center?

Brimley: Yes,

very much so.

Point No. 2: When you look at the mechanics of what we did

in Libya, we provided a set of capabilities that were unique. We had unique

comparative advantage: air- to-air refueling, ISR

architecture, command-and-control architecture.

Alford: Geography

mattered on that too.

Brimley: Geography,

yes absolutely. The fact that we had a presence in the Mediterranean already

was very helpful.

Alford: And you

have an ocean.

Brimley: Right.

We provided this set of unique capabilities that were enabling for other

partners, to include partners from the Gulf to act in ways that they hadn't

before. Every situation is different.

But I think that process, at least for someone like me

relatively young, as a case study in how we think about how we think about

use-of-force decision-making and the way we provide unique capabilities in the

future is hugely informative.

The second thing I'd say on Libyais that as a young person,

my limited experience dealing with these issues has been informed almost

entirely by Iraq and Afghanistan. So when we were debating Libya, people in my

generation were very sort of hesitant to really almost do anything. Almost a

hard-core realist approach of "it's not really core to our national

interests; we shouldn't get involved." But the people, I think, who had

came of age in the Clinton administration who dealt with limited uses of force

-- no-fly zones -- were much more willing to entertain creative solutions. So

people in my generation, I think, going forward will tend to be an all-in or

all-out.

Ricks: There's an

article to be done there on the generational qualities in foreign policymakers.

Brimley: I think

the people within the Clinton administration having dealt with a couple of

these use-of-force decisions in the ‘90s were much more creative in how they

thought about ways in which we could use force but not go all in.

Alford: A great

example, real quick. I was a second lieutenant in Panama when we took out

Noriega. And by December 26th the Panamanian people were on our side, but that

could have easily been a counterinsurgency fight, but the Panamanian people

were very Americanized. We invaded that country, took out its leader, and

rebuilt it. And it happened like that because the Panamanian people said yes.

By February I was home, drinking

beer.

(More to come about, especially about

the relationship between golf and force structure)

If we don’t want to be like the Iranians and get Stuxnetted, take these 4 steps

By John Scott

Best Defense guest columnist

It's Wednesday, and that means another story about the looming threat of cyberattack, how vulnerable

the United States and its infrastructure is, how bad the Chinese are, how to

retaliate, etc. But what seems to be left out of the discussion is what can practically

be done about it (beyond scolding bad people).

The first thing that should be done is to shrink surface

area for attack. What does this mean? Right now the U.S. government and

industry runs a pretty homogenous set of operating systems and applications

that have shown to be a big part of the problem; specifically, Microsoft and

Adobe are two companies whose wares have become amazing attack vectors. Why?

For a few reasons: 1) if you want to create a virus/exploit weapon you tailor

one for largest adoption, 2) attack large morphing code bases that give rise to

known-unknown software vulnerabilities, and 3) updates don't always filter out

in time once new vulnerabilities are detected and patched.

A great example is how Stuxnet is reported to have entered the Iranian nuclear program:

The main (and initial) infection vector is the transmission of the

Stuxnet malware via USB devices: if an infected USB device is inserted into a clean PC and later accessed with the

Windows Explorer, then the infection of that PC is triggered. This is due to

either a malicious ‘Autorun.inf' file present on the USB device (for the oldest

variants of Stuxnet) or to the usage of the ‘LNK' Windows vulnerability

(MS10-046,CERT-IST/AV-2010.313 advisory) for the variants found in June

2010.

The Iranians were probably running older versions of

Microsoft operating system software that wasn't updated (and was probably

pirated to boot). Further, the Iranians were a victim of Microsoft's

business model of stitching together source code to lock-in users and

conversely lock-out other software, which allowed the virus carte blanche

access to anything.

So what should we, the government, or private companies

for that matter, do? First thing, we've got to get our own house in order to

limit our vulnerabilities (or "know thyself," to paraphrase Sun Tzu).

First, get rid of software for which we have to

continually make excuses. Just as the U.S. military doesn't promote smugglers

(Han Solo) and farm boys (Luke Skywalker) to general, stop deploying

software that requires additional fixes and comes stitched together. Microsoft

and Adobe might be less expensive software, but if it leaves a backdoor open,

is it really "cheaper"?

Second, only install operating systems and applications

where the source code is available for widespread public inspection. Keeping

source code secret increases its widespread vulnerability to exploitation when

a defect is detected.

Third, increase heterogeneity of operating systems and

applications to create gaps so that a virus/exploit can't transverse between

different systems.

Fourth, fund research into more secure operating

systems and make the fruits of that investment public: A rising tide lifts all

(security) boats. A small investment in maturing source code can have a large

impact.

John Scott is a senior system engineer for Radiant

Blue Technologies and was a co-author of

Open

Technology Development: Lessons Learned and Best Practices for Military

Software

(Department

of Defense, 2011). He occasionally blogs at

Powdermonkey

.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers