Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 115

April 11, 2013

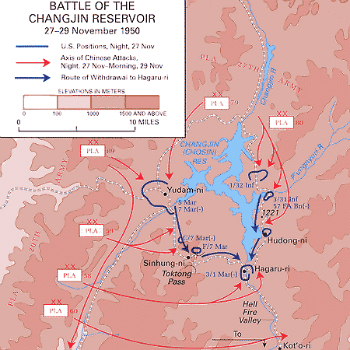

Body of Lt. Col. Don Faith, a key figure in the Chosin campaign, is found in North Korea and brought home after 63 years

I always read the

Pentagon casualty notices and MIA notices. This one jumped out at me yesterday,

as it would to anyone familiar with the history of the Chosin Reservoir campaign.

Lt. Col. Don Faith,

Jr. was the unfortunate leader of one of the biggest disasters in American

military history, taking over command of the Army regiment on the east side of

Chosin after the commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment was killed and the

other two battalion commanders were badly wounded. The regiment, badly

outnumbered and hampered by inept general officers, suffered a 90 percent

casualty rate. Its colors now are displayed in Beijing, I am told.

However, the

sacrifice of the Army regiment bought much-needed time for the Marine division

consolidating on the west side of the reservoir.

Soldier Missing from Korean War Identified

The

Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that

a serviceman, who was unaccounted-for from the Korean War, has been identified

and will be returned to his family for burial with full military honors.

Army

Lt. Col. Don C. Faith Jr. of Washington, Ind., will be buried April 17, in

Arlington National Cemetery. Faith was a veteran of World War II and went on to

serve in the Korean War. In late 1950, Faith's 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry

Regiment, which was attached to the 31st Regimental Combat Team (RCT), was

advancing along the eastern side of the Chosin Reservoir, in North Korea. From

Nov. 27 to Dec. 1, 1950, the Chinese People's Volunteer Forces (CPVF) encircled

and attempted to overrun the U.S. position. During this series of attacks,

Faith's commander went missing, and Faith assumed command of the 31st RCT. As

the battle continued, the 31st RCT, which came to be known as "Task Force

Faith," was forced to withdraw south along Route 5 to a more defensible

position. During the withdrawal, Faith continuously rallied his troops, and

personally led an assault on a CPVF position.

Records

compiled after the battle of the Chosin Reservoir, to include eyewitness

reports from survivors of the battle, indicated that Faith was seriously

injured by shrapnel on Dec. 1, 1950, and subsequently died from those injuries

on Dec. 2, 1950. His body was not recovered by U.S. forces at that time. Faith

was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor -- the United States'

highest military honor -- for personal acts of exceptional valor during

the battle.

In

2004, a joint U.S. and Democratic People's Republic of North Korea (D.P.R.K)

team surveyed the area where Faith was last seen. His remains were located and

returned to the U.S. for identification.

To

identify Faith's remains, scientists from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command

(JPAC) and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) used

circumstantial evidence, compiled by DPMO and JPAC researchers, and forensic

identification tools, such as dental comparison. They also used mitochondrial

DNA -- which matched Faith's brother.

Mission command is harder to do than the Army thinks -- and requires a lot of inputs

By

"Misha N. Komand"

Best

Defense guest correspondent

How can we really enjoy the benefits of mission

command without the inputs? You don't just 'do' mission

command (just as you don't just 'do' Army design methodology).

The Germans didn't just 'do' Auftragstaktik.

No, it was built on a culture that held junior

officers on up to rigorous accounting of academic and military ability. The

Army thinks it can incorporate the benefits of an idea by simply incorporating

(or poaching) the good terms or ideas of others, and not have to pay the price

in selecting and educating the right officers. There will be no true mission

command without a cultural change starting with accountability in education

(centering on military history) and better selection and shaping of the officer

corps.

"Misha N. Komand" is

an active duty Army officer serving on the periphery of the American dream.

Tales of the Afghan military: Honestly, which officer here hasn't raped a tea boy?

Ugh.

Maj.

Charles Wagenblast, a military intelligence

reservist, brought home this story from Afghanistan about an Afghan colonel:

One of

the colonels that we both knew had been accused of raping a chai boy, badly. They all have chai boys, it's not some perverted

thing, it's just what they do. Women are for juma. The only time you

interact with your wife is on Friday, the rest of the time it's chai boys. He had been raping this chai boy, which is normal, but he had

hurt him really bad. That caused the medical people to get involved and other

forces. So he's there in front of the judge, who is an imam. It's

religion mixed with law, the whole code of law would fit in a pamphlet and then

there's the Koran there on top of it. Anyway, his defense was, "Honestly,

who hasn't raped a chai boy? Ha ha

ha." And the judge goes, "You're right. Case dismissed."

April 10, 2013

'Way of the Knife': Mark Mazzetti's lively tour of the third war we've been fighting

The estimable Micah

Zenko wants a "first

draft" of "the Third War." Actually it has been written, and is

being published this week. It is The Way of the Knife,

by Mark

Mazzetti. It has all sorts of interesting details, like

that the United States has the ability to remotely turn on a cell phone in

Pakistan and then collect the precise coordinates of whoever is carrying

it.

Here is an interview I did with the author by

e-mail:

Tom Ricks: What are we going to learn from your book that

we haven't gotten from others, like those by Peter Bergen?

Mark Mazzetti: Peter's books are

absolutely terrific, and a hard act to follow! And, there have certainly been a

number of terrific books covering the war on terror. What I've tried to do in

my book is tell a story of a secret war, and how that war has changed places

like the CIA and parts of the Pentagon. The CIA is now at the center of waging

covert wars in places like Pakistan and Yemen. The agency certainly has had a

history of far flung military adventures, but then it tried to get out of the

killing business -- only to come back at it in a big way since the September 11

attacks. Meanwhile, the Pentagon has become more like the military, sending

soldiers into the dark corners of the world on spying missions. There's been a

real blurring of the lines between soldiers and spies.

With the "big wars" in Iraq and

Afghanistan either over or winding down, I think that these secret wars have

become the default way of doing business. And, only now is the pressure growing

for the White House to bring greater transparency to the shadow wars.

TR: What was the biggest surprise to you in reporting and

writing the book?

MM: I think that the biggest surprise

was how much this type of warfare brings various colorful characters to the

forefront. When the United States determined it couldn't send the 101st

Airborne into a country, it began to rely on private contractors and other

types of individuals to do things like gather intelligence on the ground. I

spent a chapter on the private spying network run by Duane Clarridge, a former

CIA officer and one of the figures in the Iran-Contra scandal. A Pentagon

official hired Clarridge's team to gather intelligence in Pakistan because

there was a belief that the CIA wasn't up to the task, but the entire operation

ended up in recriminations and a Pentagon investigation. It's stories like this

that I really tried to highlight in the book.

TR:

Why do you think

drones have become so controversial only recently in the United States?

MM: That's a good question. I think

that up until recently, at least in Washington, you had both Republicans and

Democrats uniformly supporting targeted killings and there was no constituency

calling for greater transparency and accountability for these kinds of

operations. Since the November election, you have seen Democrats become more

vocal in challenging the Obama administration on the use of targeted killings.

And, of course, there is Rand Paul's now-famous filibuster that captured

concerns among Libertarians about secret government operations.

TR: Which of our three wars (Iraq, Afghanistan, and "knife")

do you think historians ultimately will find the most significant?

MM: This might sound like I'm

avoiding giving a direct answer, but all three wars have impacted each other,

and so in some ways I think that some historians will look at this entire post-9/11

period as one that fundamentally changed both U.S. foreign policy and how the

United States conducts war. Certainly, the Obama administration has relied on

these shadow wars because it considers them cheaper, lower risk, and more

effective than the big messy wars of

occupation like Iraq and Afghanistan. But, so much of the way that an

organization like the Joint Special Operations Command does business is a

direct result of its work in both Iraq and Afghanistan. They took parts of what

they were doing in those countries and brought outside of the "hot"

battlefields.

TR: What do you think are the lessons

of this third war?

MM: There's no question that the United States has become

dramatically better at manhunting than it was on September 11, 2001. There is

better fusion of intelligence, and the Pentagon, CIA, and other intelligence

agencies are working more closely together. I think, though, that one of the

lessons is that secrecy can be very seductive and that it might be too easy for

our government to carry out secret warfare without the normal checks and

balances required for going to war. As you well know, as much as the Pentagon

can be a lumbering bureaucracy, there is a certain benefit of having a good

many layers that operations must pass through in order to get approved. When

decisions about life and death are made among a small group of people, and in

secret, there are inherent risks.

Is the West Point superintendent, Gen. Huntoon, guilty of an honor violation?

It looks

like that may be the case. But we don't know because he and the Army are

stonewalling. They're hiding behind a statement that an allegation of an

improper relationship was investigated and was unsubstantiated, and that he is

retiring as planned.

But they

aren't saying what was substantiated. The Washington Post found out through a FOIA request that the Defense

Department inspector general did find some wrongdoing. So it appears to me that

General Huntoon misled me when he told me in January that "there's no

investigation here." Which leads to the question: Are cadets held to a higher

standard of conduct than superintendents?

As of 10 am

today, General Huntoon hasn't responded to the question I sent him last weekend

asking him what is going on.

Remember the Iraq war?

Nathan

Webster does. Check out some of his recent work.

April 9, 2013

The Army and the mirror

Does anyone

know of any official Army publication that critiques and compares the

performance of Army generals in Iraq? I can't remember any, but 10 years is a

long time and there is a chance I have forgotten something.

I don't

mean individual articles in Military

Review or papers written at the Command and General Staff College. I've

read (and quoted) those in my last three books. What I mean is official

publications like On Point (which was

good) and On Point II (which wasn't).

That is, the studies that carry the imprint of a preface by a sponsoring

three-star or four-star officer.

If not, why

not? Is the Army really going to take the Lake Woebegone line that all its

generals were above average? Or is just going to fold its arms and believe that

such criticism is too rude for public discourse?

Speaking of

generals, I still haven't heard back from Lt. Gen. Huntoon about the nature of the

misconduct the IG found him to have committed.

You miss Maj. Mcilwaine?: OK, here are 10 more lessons from post-9/11 conflicts

By Kyle

Teamey

Best

Defense department of COIN rehabilitation

1. Regime change IS nation building.

Whether the intention is to stop ethnic cleansing or to affect a

change in policy by a rogue nation-state, the result of regime change is the

same -- a long period of rebuilding. In a multi-ethnic state with no history of

democracy, a period of violent turmoil should be expected after a regime is

toppled. It must either be managed directly by the United States (Iraq and

Afghanistan) or groups supported by the United States and allies (Libya).

2. A minimal U.S. footprint is the preferred way to do COIN...when

feasible.

An overlooked writer on the subject of counterinsurgency (COIN)

is Thomas Mockaitis. He took some very

good lessons from the United Kingdom's 20th century experiences in COIN and

summed them to three best practices that marked successful campaigns: minimal

force, civil-military cooperation, and tactical flexibility. The minimal force

part of that equation is critical. It often means minimizing the use of third

party forces because of the high probability that the third party adds to the

conflict simply by being present. An additional benefit of minimal use of force

is minimizing the costs to the United States in blood and treasure for a given

conflict. Recent efforts in Colombia, Yemen, Somalia, El Salvador, and the

Philippines where the U.S. supported COIN and counterterror efforts with few or

no U.S. troops are instructive. Minimal use of U.S. forces has been relatively

successful and low cost. That said, we really did not give ourselves an option

for a small footprint approach in Iraq. There was no other organization to step

into the post-Saddam power vacuum and leaving a total disaster in a

strategically important part of the world was not an option. See #1 above.

3. Small U.S. footprint or large, the principles of COIN are the

same.

Regardless of who is doing the COIN campaign or how the United States

is supporting the campaign -- foreign aid, foreign internal defense, advisors,

boots on the ground, etc -- the rules are the same. Best practices are best

practices no matter who utilizes them. We are constrained by law and social

norms to something that looks like population-centric COIN whether we do it

ourselves or support a third party. The government has to be legitimate, the

people have to be protected, there must be unity of effort amongst the

counterinsurgents, intelligence must drive operations, there must be unity of

effort amongst civil and military authorities, and the insurgents must be

exposed to security forces. The argument that we should "just kill all the

insurgents" is noise. Due to aforementioned law and social norms, killing

bad guys requires separating them from the populace, which doesn't happen if

the government is not legitimate, the people are not protected, etc. It should

also be noted that killing bad guys is one of the most important parts of

population-centric COIN. The argument that population-centric COIN only means

"hearts and minds" where everyone sits around drinking tea and singing together

is a strawman. Depending on conditions on the ground commanders may weight

their efforts more towards the use of force or more towards stability

operations, but there will always be an element of violence, or the threat of

violence, in population-centric COIN.

4. War hasn't changed: Good tactics don't matter if you are

operationally or strategically inept.

We proved this in spades in Iraq, where some units did things

well, others poorly, and there was initially no over-arching planning or

coordination for the post-regime era. We did pretty much everything wrong from

2003 to 2007 and got lucky it didn't go worse than it did. Get good generals

who know what they are doing. Fire those who don't. Sounds simple but it ain't.

5. If you want to defeat an insurgency, don't let the insurgents

have a safe haven.

Pakistani tribal areas, Fallujah in 2004, other "no

go" areas in Iraq in 2004-6, the FARC zone in Colombia, FARC camps in

Ecuador and Venezuela, etc. Nothing good comes of allowing a safe haven for

insurgents. Ever. If we are serious about defeating an insurgency, we should

never allow any safe havens. If national goals are limited to keeping the

insurgency down to a dull roar or killing some terrorists, then a safe haven

may be tolerable.

6. Rotate troops

effectively or it will be a "Groundhog Day" war.

U.S. troops fighting overseas need time to rest, relax, and be

with their loved ones. In short, they need to regularly rotate out of theater.

Unfortunately, this creates a major dilemma when using U.S. troops to conduct

long-term COIN operations. As in the movie "Groundhog Day," every rotation can

effectively create a new beginning to the same war. New relationships must be

(re)forged between the host nation and the incoming U.S. personnel for

operations to be effective. The identity and modus operandi of insurgent groups

and leaders must be (re)learned. The learning curve is very steep, and by the

time the troops know their "neighborhood" it is time to go home -- Groundhog Day

all over again. There are ways to mitigate the deleterious effects of troop

rotations, for instance, through the use of information technology or by

rotating units to the same locations in theater, but they cannot be avoided

altogether.

7. COIN lessons from Iraq have been misapplied in Afghanistan.

The tactics borrowed from Iraq for use in Afghanistan have

generally been effective. Applying a lot of flexibility to account for the vast

differences between the theaters, many of the tactics seem to work pretty well

at the brigade and below. Unfortunately, the operational and strategic lessons

from Iraq and prior conflicts have not been as well applied. In the absence of

a legitimate government, population-centric COIN does not work. If insurgents

have a large sanctuary where they can rest and refit, COIN has a high

probability of failing. If there is not unity of effort amongst civil and

military authorities, COIN has a high probability of failing. All of these are

problems in the Afghan theater. The government is, at best, tolerated. Pakistan

provides a massive refuge with endless border crossings. The leadership of

Afghanistan has an often rocky relationship with that of the United States and

attacks on U.S. troops by Afghan troops are commonplace. Under these

conditions, the best tactics cannot succeed in defeating the insurgency. Add to

these factors an inordinately large number of theater commanders over the

course of the campaign -- five in just the last five years -- and it is clear

the U.S. goal of defeating the Taliban did not align with practical realities.

See #3, 4, 5, and 6 above. It seems we ignored first principles in Afghanistan

and just hoped good tactics would win the day. Not a good approach. It is

understandable strategic leaders might judge it is too costly to do population-centric

COIN in the Af/Pak region "correctly," and that dealing with the Pakistani

tribal areas directly is infeasible. Under such circumstances, we should be

honest with ourselves that we cannot defeat the insurgency outright, align

goals with what is possible, and field a force that makes sense for the more

limited goals.

8. Detainee operations are much too important to be left to

amateurs.

We have completely messed this up since 9/11. Our tactics in

dealing with detainees have had such undesired effects as alienating allies,

angering large portions of the U.S. electorate, alienating portions of the

local population in countries where we operate, and reinvigorating Iraq's

insurgency with the Abu Ghraib prison scandal. We also conducted detainee

operations poorly for long periods of time. Initially large numbers of people

in Iraq were rounded up and sent to detention facilities for no good reason.

Later in the conflict we released a very large percentage of insurgents within

6-18 months of capture...often because the capturing unit had rotated back to

their home station. See #6 above. Insurgents came back from prison better

connected and with greater street cred. It was like a nightmarish National

Training Center rotation where the bad guys get a re-key and our troops get

shot or blown up by now better-trained insurgents. I thought Catch-22 was funny

until living it! Our poor detainee tactics in the time after 9/11 had very

negative operational and strategic impacts. If we ever do COIN again using U.S.

forces, it is imperative we get this right. To borrow from David Galula,

"Under the best circumstances, the police action cannot fail to have negative

aspects for both the population and the counterinsurgent living with it...these

reasons demand the operation be conducted by professionals..." -David Galula,

Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice.

9. Democracy and governance start from the bottom.

In Iraq, the Coalition Provisional Authority made a huge mistake

by disallowing local and regional elections until there was a national

constitution in place. We created a power vacuum that could only be filled by

traditional leaders (sheikhs and imams), insurgents, and coalition forces.

During the years it took to get a national government in place, we should have

been encouraging local elections to build experience with democracy, form

political parties, and create locally legitimate governance. Rule by the people

has to be built from the bottom up. The U.S. experience is instructive. The

presence of functioning state and local government allowed national leaders the

time to hash out a constitution. It took our founders about 12 years to get a

constitution written and approved... and that was with two tries because the

first attempt failed. We expected the Iraqis and Afghans to get it done in a

year or two and create an effective system of governance though they have no

experience in democracy, no political parties, traditional leaders or U.S.

troops trying to fill the role of local government, and a raging insurgency

that leaves a large portion of their population disenfranchised? That's nuts!

10. Maintain training and doctrine related to COIN.

We will do it again. We always say we won't and we always do.

It's too costly in lives and dollars to not keep this in the doctrine. Don't

make another generation get maimed unnecessarily.

Kyle Teamey is a major in the U.S. Army Reserves. He served on

active duty with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and 1st

Infantry Division from 1998 to 2004. After leaving active duty, he served as a

civilian counterinsurgency analyst from 2005-2006, co-authored the 2006 edition

of FM 3-24 Counterinsurgency, and assisted DARPA in the development and fielding of the Tactical

Ground Reporting System (TIGR) from 2005 to 2009. He is currently the chief executive

officer of a chemical technology company.

Livefyre sure sucks

There. Got it off my chest. Just had to

say it. Slow to load, balky to use.

And my blood pressure spikes every time

I read that cheerful, dumb introduction, "Welcome to

Foreign Policy's new commenting system! The good news is that it's now easier

than ever to comment and share your insights with friends."

Like I say, the bad news is the new

commenting sucks! That's the insight I wish to share.

As one reader commented recently, "the Battle of the Somme was a model of efficiency in comparison to 'Livefyre.'"

April 8, 2013

Army senior officer police blotter: Sex, alcohol, child porn, and something else

Maj. Gen.

Ralph Baker, commander of CJTF-Horn of Africa, got the big boot for personal misconduct related to sex and

alcohol, the ham

and eggs of flag officer troubles.

The Washington Post's Craig Whitlock

reported over the weekend that the Pentagon's inspector general upheld charges

of misconduct by two three-star Army generals, Joseph Fil and David Huntoon. "Records

obtained by The Post," he wrote, "show that the Pentagon's inspector general

also substantiated misconduct charges last year against Huntoon, the West Point

superintendent." This surprised me because when I heard in late January about

Huntoon being investigated, I asked him about it, and he basically flatly

denied there was anything to what I had heard. "There is no investigation

here," he said. So this past Saturday morning I sent him a note asking why he

said that. As of 10 am this (Monday) morning, I haven't heard back from him.

The Post didn't have specifics on

what the misconduct in question was. For all I know, it could have been

aggravated jaywalking. If so, I wish General Huntoon had said that at the

time.

Finally,

Col. Robert Rice, who works in war-gaming at the Army War College's Center for

Strategic Leadership and Development, was suspended after being charged on a

bunch of counts of having child porn on his personal laptop.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers