Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 117

April 3, 2013

Press criticism, Iraqi style

Fifty Shiite gunmen invaded

the offices of four newspapers in Baghdad. They

smashed equipment, stabbed some people, and threw one reporter off the roof.

Let freedom reign?

April 2, 2013

Hey, JOs: Want an interesting career plus a life? Come to the Guard and Reserves

By Brig. Gen. James D.

Campbell

Best Defense Guard

columnist

One of things I find most interesting, and even objectionable,

in the entire discourse between these two senior officers is the fact that, clearly, neither of

them recognizes or even considers the reserve components as part of "the

Army."

Many of the talented young officers and NCOs who

are choosing to leave the active force are, in fact, transferring to the

National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve. So in that sense, "the Army"

isn't losing these experienced young leaders. That is, we're not losing them if our active counterparts view the

Guard and Reserve as part of the wider team. Even more of these junior leaders

would choose the Guard and Reserve if active duty senior leaders actually tried

to present service in the Reserve Components as a viable option for those who

want to keep serving but also want stability for their families along with

different career and educational opportunities. Unfortunately, as judged by

these essays in FP, most senior Army

leaders don't ever even think of the reserve components as really part of

"the Army." Personally, along with many of my peers I left the regular

Army in the early '90s after almost 10 years of service and have been in the

Guard ever since. I've managed to have a full, reasonably successful career,

and have gotten to do a lot of things on the civilian side I never would have

done had I stayed on active duty.

This paradigm of leaving the reserve components

out of the equation has all sorts of corollaries: The refusal, for example, of

senior Army leaders to consider that, based on the recent Reserve Forces Policy Board report showing that the reserve components (RC)

cost only one-third the amount of the active components (AC), shouldn't we seek

to grow the RC as we must shrink the AC in order to retain the military

capability and force structure at less cost, and therefore have a flexible

"surge" capacity for emergencies? Aside from the fact that this is

effectively what we have done post-conflict throughout the entire history of

our nation, the cost pressures alone would dictate that it is a very

intelligent option. In addition to saving force structure and capability, we

would also be saving enormous numbers of proven, combat-experienced officers,

NCOs and soldiers by keeping them in the uniform and having them around for the

long term. Unfortunately, what we are hearing from senior Army leaders is that

they want to keep the AC as large as possible, even if that means cutting the

RC -- an idea that flies in the face of fiscal reality, the past 12 years of

actual operational experience, U.S. military history and tradition, and serves

as yet one more glaring reminder that our current generation of senior leaders

has never accepted the RC as equal, capable elements of the overall force. Cutting

off the nose to spite the face...

I invite all high-caliber junior and mid-grade

leaders in our Army (and Air Force) who are seeking a change and want more

stability for their families, more interesting assignment and career

opportunities, and challenging educational opportunities to look into joining

the National Guard in their home states or the states where they'd like to

live. We have been the key component of our nation's military since 1636, we

are in many ways the sole remaining repository of many of the best traditions

of the service, we listen to our people (we have to in order to keep our

high-performing, traditional part-time leaders in uniform), and we are still on

the front lines around the world. We are also still the only part of the force

which can legally and rapidly respond to assist our local communities when they

are in need.

BG James D. Campbell, Ph.D. is the adjutant

general of the Maine National Guard.

If military leaders were serious about retaining talent, they'd collect some numbers on who is leaving and why

By Maj. Peter Munson, USMC

Best Defense commission on junior officer

management

The recent battery

and counter-battery

of general

officer articles on talent

management in the face of a military drawdown is doing little to advance

the debate toward any solution -- or even agreement on the problem. The

debaters are undermined by their hyperbole. Surely, not all of the military's best officers are leaving. On the other hand,

from the volume of complaint, it seems sure that there is something awry with

talent management in the armed forces. A more qualified assertion would be that

more top talent is leaving the

military than should be the case. Yet, as deeply as I believe this statement to

be true, I cannot prove it. Therein lies the greatest problem: a personnel

system that seems not to have a measure of its success or failure in retaining talent vice retaining numbers.

The sad fact of the matter is that we lack the data to fully define the

talent management problem, so there is no way to come up with meaningful

proposals for solutions. This is a debate characterized by hyperbole and

personally charged anecdotal evidence because real data on the phenomenon are

almost completely lacking. The fact that the armed forces do not apparently

collect data on departing servicemembers for talent management purposes is

telling. There is a healthy stable of data available on each servicemember:

performance evaluations, standardized testing, civilian and military school

standings, physical fitness tests, and so on. Correlating these data to

retention and separation propensities should be a relatively easy thing, but as

far as I can tell, this work has not been done and it seems not to have been

released into the public domain.

Yet, even with the existing

data, we have a problem. While we have top-down performance evaluations,

physical fitness, and IQ-like intelligence test data, these data leave out what

may be the most important dimensions of leadership. There is no widespread data

on emotional intelligence, personality type, or 360-degree perspectives on military

officers, even though these tests are readily available and could easily be

done for those screening for key billets, or for a sample population of

separating officers. These would also be an extremely useful statistic when

considering who is getting out and who is staying in.

Absent these data, we have to

rely on works like that of Tim Kane, former Air Force officer, Ph.D. economist,

and author of the book Bleeding Talent: How the US Military

Mismanages Leaders and Why It's Time for a Revolution. Sadly, the lack of data left Kane to

rely on opinion polling -- what people perceived about the talent of those

leaving the military and their reasons for doing so -- rather than first-order

data. This method left Kane's conclusions open to dismissal by the powers that

be, but the indictment is really on a system that has no knowledge of its own

talent challenges.

As long as there are no

publically available data on these issues, each side in the debate about talent

retention in the military is informed only by their personal choices and the

anecdotes that validate that choice. There cannot be a truly informed debate

without some facts to start from and, inexplicably, these facts are completely

lacking. If senior military leaders were serious about talent retention, these

data would already be at their fingertips.

Peter J. Munson is a major in the U.S. Marine Corps. Though selected

for lieutenant colonel, he is leaving the Marine Corps with sixteen years of

service this summer. He is the author of War,

Welfare & Democracy: Rethinking America's Quest for the End of History (Potomac, 2013).

Quote of the day: What one JO wants

From a blog comment posted

on Sunday evening:

I crave autonomy, a sense of meaning in my work, and to have

some semblance of self-determination in my career. My first two desires were

met more often than not while I was deployed to Afghanistan for the last nine

months. However, I'm not entirely sure that will continue now that my unit is

back in garrison and no longer on a patch chart. We have returned to an

environment of repetitive briefings and seemingly endless bureaucratic forms,

and all the while there are whispers of funding problems canceling

opportunities for military schools and substantive training events. Time will

tell if we head the way of incessant drill and ceremony practice augmented by

pay day activities and area beautification. Truth be told, I do not know

because I have never been in a unit that is not preparing to go to war, but

this is the fear. The fear is we will spend hours laying out and cleaning

equipment that we can't train with. That our training will be on making perfect

Powerpoint slides instead of rolling up our sleeves to enable sergeant's time.

April 1, 2013

What President Obama should say about North Korea’s provocative statements

By Lt. Gen. John H. Cushman, U.S. Army (Ret.)

Best Defense guest columnist

This is what the president should say:

Organs of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea have recently made announcements of that nation's readiness to attack

with long range weapons targets of the United States.

It is time for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea to

cease such behavior and to join the community of nations.

The United States has no intention to attack the Democratic People's

Republic of Korea.

If under any pretext the Democratic People's Republic of Korea attacks

the United States, we will respond with devastating might. Their nation will be

a wasteland.

Leaders of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea have built military

weaponry that can serve no useful purpose.

I repeat, it is time for them

to cease such behavior and to join the community of nations.

End of conference

General

Cushman commanded the 101st A

irborne Division, the Army Combined Arms Center, and the

ROK/US field army defending Korea's Western Sector. He served three tours in

Vietnam. He also is author of

C

ommand and Control of Theater Forces: The Korea Command and

Other Cases

(1986).

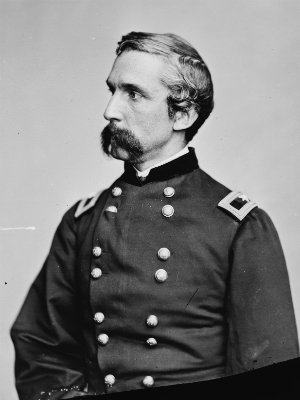

The Hodges-Barno smackdown: A view from the cheap seats of a junior officer

By "Si Syphus"

Best Defense junior officer panel

"Let's get ready to RUMBLE!" I can just picture

Michael Buffer

announcing the upcoming "prize fight."

In the blue corner stands Lt. Gen. (R) David Barno and in the red corner stands

Lt. Gen Fredrick ‘Ben' Hodges. The main event: Are we losing talent in today's Army?

Reading the differences between senior leaders

is quite hilarious. I would equate it to watching two dudes argue about (insert

sports teams here), in an alcohol-induced stupor, less the possibility of

violence. Both bring up valid points, yet one uses "how they see the facts" to

support their argument. However, no matter who is right and who wrong, what is

lost in translation is the actual premise of the argument -- in this case

junior leaders -- and nothing is done to rectify the situation. The end result

is an epic 12-round bout with a split decision resulting in a draw, and a

re-match likely on the horizon in a couple of years.

Lt. Gen. (R) Barno's "Military

Brain Drain" echoes the position of Tim Kane's Bleeding Talent,

stating that "if you ignore the expectations of today's young,

combat-experienced leaders as you shrink the force, your most talented officers

and sergeants will exit, stage left." Both Barno and Kane lament protecting the

"crown jewel" of talented junior leaders is required for future success.

On the other hand, Lt.

Gen. Hodges disagrees with Barno's supposition that there is

a "brain drain" in the Army based on four main points: 1) junior officers are doing

good things deployed, 2) there are "broadening" opportunities, 3) what his

peers have to say, and 4) senior leader examples.

My response, for what it's worth:

Round One: Yes,

junior leaders are doing exceptional things while deployed. That is because

there is "freedom of maneuver." Problems are complex and our junior leaders are

excelling with the opportunity to demonstrate their innovativeness,

adaptability, and unique ability to solve the complex issues. However, when

these junior leaders come home, this ability is stymied due to the fact of not

being at war. The "garrison" Army was, is, and will continue to be a polar

opposite to war-time. Junior leaders, ones that currently have less than 12

years of service, know absolutely NOTHING about "garrison." We are

operationally minded, doing one of three things: prepare to deploy, deploy,

recover. This has been the cycle, but that is about to change. Bottom line: There

is not enough money or incentives in the world that will be able to keep 100

percent of the targeted group to stay in the Army, unless there is a change.

Round Two: Lt. Gen.

Hodges mentions various things that the Army is offering to junior leaders --

"the best and most expensive" universities, fellowships, and training with

industry. Let's be honest, all of these things are pretty cool and the fact

that it is an option, also pretty cool. However, let's be realistic. The Army

has the Olmstead Scholarship -- one per year. Congressional fellowships -- 25

per year. Advanced civil schooling -- a generous figure would be 400 per year.

A realistic amount of junior leaders receiving this "broadening" any given year

would be about 600. However, when applying for these opportunities, a junior

leader is grouped with a total of about three year groups' worth, or about

6,000 other people. So this "broadening" is available to about 10 percent of

junior leaders. If the target is to retain the "top 20 percent" and this is all

the incentive, then we are falling short. Don't get me wrong, this is a good

start. But let's not use this as the be-all end-all answer to saying quality

junior leaders are not leaving. This is more of a "look what we are going to

keep some of the talent."

If you have sipped the green Kool-Aid and are

immersed in current Army rhetoric, now might be a good time to stop reading.

Otherwise, you might berate me as a junior leader who doesn't know shit.

The following two examples are used by Lt. Gen.

Hodges to support his argument that I take issue with the most:

Round Three: Lt. Gen.

Hodges starts his argument saying he is "disappointed" in Barno's position

because it is not something he sees or hears in his "dealings with senior Army

leaders" or his peers. (Ok, I am going to believe it now because a bunch of

crusty old men are saying it's not true. Sure.) I'm pretty sure this is the

whole "group think" mentality we are trying to go away from. What about

"outside the box" thinking? Apparently this only applies to junior leaders.

What do other senior leaders and other generals know about why junior leaders

are staying in? I got an idea: How about asking them and not your peers.

Lt. Gen. Hodges also claims that Barno's

comments about the best leaving are "an insult to the thousands staying." Not

the case. I stayed, and I'm not insulted. Lt. Gen. (R) Barno or Tim Kane never

referred to me as "not talented" because I chose to stay. I understand where

they are coming from when they point out the facts that quality junior leaders

have left up to this point (true) and quality junior leaders will continue to

leave until this situation is rectified (also true). I'm not drinking the

Kool-Aid and buying into a senior leader telling me I should be insulted for

something that is the truth. I'm also not buying it just because a bunch of

them are saying it.

Round Four: The

justification I most take exception to is the "this worked for me" approach.

"Senior Army leaders

have emphasized this repeatedly and are setting an example by doing it

themselves. My own experience validates this. In 33-plus years of service and

about 25 different duty positions, there were only two times when I ended up in

a duty position I had specifically requested or pursued. Every other assignment

was the result of personal intervention of commanders, mentors, or some senior

leader in the span of my career who wanted to invest in me and prepare me for

greater challenges. That has been my experience- indeed, that is the norm I

have witnessed for over three decades- and it's the legacy I have tried to pass

to others."

This statement is

what is wrong with our current Army and exactly the premise that Barno and Kane

are using to explain the exodus of talented junior leaders. Just because this

worked for Lt. Gen. Hodges does not mean that it will work for all current

junior leaders or for that fact even the majority. While this style might have

worked for Lt. Gen. Hodges's three decades of service (20 of which were

predominantly during times of peace), this should not be the direction of the

future.

The Army currently is

structured in such a way that in order to be successful, you have to meet

certain "gates" at certain times. If you don't meet them, no matter how much

talent you possess, you are considered "at-risk" for advancement, as well as

ineligible for any of the extra incentives Lt. Gen. Hodges invoked. Likewise,

it doesn't matter who you are, if you checked the right block at the right

time, then you are good to go. Hypothetically speaking here, what is wrong with

a captain who doesn't want to be a commander but makes a great intelligence

officer, signal officer, or whatever staff position? If he or she had the

opportunity to continue as a staff officer, he or she could be an integral

component of the team. Why must that individual be a commander, where he or she

might not excel, just to be eligible for promotion?

Let's take an example

of two Army captains. In this example, all things are equal. They are in the

same year group and have the exact same jobs. Captain #1 has been stationed at

Ft. Hood (heavy) for 3 years, and wouldn't mind staying for another 3 years.

Captain #2 has been stationed at Ft. Drum (light) for 3 years and really wants

to go to Ft. Bragg (also light). Captain #1 receives orders for Ft. Bragg

because he doesn't have light experience. Captain #2 receives orders for Ft.

Hood because he doesn't have heavy experience. Why is it not possible for the

two to switch and be happy? Well, it has been determined that in order for both

to be successful, they need to be diverse. The outcome of this scenario: two

disgruntled junior leaders who might end up deciding to get out. On the other

hand, had the opportunity presented itself to get what they both wanted, both might

stay in.

Nowadays people want

stability over anything else, especially as we begin to emerge from a decade at

war. I would venture to say that this is the driving factor over anything else

on one's decision to "stay or go." Being obligated to pick up and move

(children are deep-rooted at a school and/or a spouse is well-established in a

career) just to check the block for promotion presents an officer with an

undesirable choice. Nobody should fault that individual for choosing to get out

-- that is, putting family first.

Rather than argue and maintain a stubborn

mindset that there is nothing wrong, or that the Army is better off without the

junior officers who choose to leave, my first recommendation is that current

Army senior leaders LISTEN to what Barno and Kane are saying on the subject.

Barno said it perfectly in his 13 February "Military Brain Drain" article:

There is no reason

not to listen and respond to the concerns of younger officers -- while also

fully meeting the needs of service. But you can't do it with a World War II

mindset, an insular outlook, or an industrial aged personnel system- all of

which are markedly in evidence today. And in the coming years, throwing money

at the problem is not likely to be as easy as in the past.

The decision: Talk to junior leaders and find

out what THEY want. Continuing down the current path won't "break" the Army;

however, it certainly will hinder it for future generations.

"Si

Syphus" is the company-grade officer sitting just a few desks away from you. Go

ask him what he thinks.

Hey, Tom: The next time you write a book, try looking up from the ground

By Lt. Col. Tom

Cooper, USAF

Best Defense aerial

book critic

In order to support our Best Defense host's

desire to learn

more about Air Force history, I thought I'd

provide an airman's perspective on The Generals.

Many reviews of Tom's most recent book ping-pong back and forth against

the Army and in

favor of the Army but make no mention of the teamwork

required to execute military operations since World War II. I don't have much

experience working under direct Army leadership but I do know that the

contributions of the joint team were not fully accounted for in the book.

The subtitle of Tom's book, "American Military

Command from World War II to Today," is not a complete statement because it

neglects all naval and air leaders who have made significant contributions to

military operations in the same period. Fortunately for the nation, more than

just the Army and Marine Corps conduct military operations. The narrow vision

of "the military" presented in the book does not fully capture the lessons of

leadership for the way joint warfighting is conducted today. It is joint

teamwork that makes American military operations succeed. And it is

perspectives born from different service experiences that help broaden the

thinking of leaders and produce the high-level of trust needed for joint

success.

Unfortunately, many assume the strategic leader

ought to wear the same "boots" as the guys sent to fight -- probably tactically

appropriate, but unproven strategically. A single-service strategic perspective

does not take advantage of the joint force the nation has prepared to fight its

wars. The Joint Task Force Commander should be surrounded by a diversity of

thought, not same-service minions that benefit from agreeing and reinforcing

the same-service leader's way of thinking. The military successes (and military

failures) of the leaders highlighted by Ricks require deeper examination

through a joint warfighting lens. Each success in The Generals embraced diverse viewpoints of how to fight over

single-service concepts.

Many people assumed that the wars of the past

decade needed leaders with a ground perspective, but leaders who can approach

problems from other viewpoints might have led to different outcomes. A

different perspective might have created innovative ways to operate in Iraq and

Afghanistan that may have cost less and risked less. In My Share of the Task,

General Stanley McChrystal's descriptions of increasing the pace of operations

of Task Force 712 to hunt Zarqawi is similar to the military challenge General

Carl Spaatz faced when put in charge of achieving air superiority before D-Day.

I don't know if General McChrystal ever studied air operations over Europe, but

the challenge of generating an operational pace that can exhaust your enemy

while not exhausting your own was a significant lesson Carl Spaatz learned in

the skies over Europe in early 1944. Similarly, "it

takes a network" rings very closely to how airmen across

generations thought about generating an effects chain to disrupt enemy actions

before "effects-based operations" became a "concept

that should not be spoken of" by a respected

senior leader.

To understand the diversity of thought brought

by different military experiences, consider the following academic example. As

an airman, I chose a path that did not train me to understand the tactics of an

infantry squad, and I have no expectation that I should lead in the infantry. However,

in choosing the Air Force, I chose a

service that develops an innovative mindset not hindered by geography and more

conscious of range.

This became particularly evident to me while

participating in a recent Army-led Antietam staff ride. The experience included the entire

South Mountain campaign and siege of Harpers Ferry,

giving a more strategic viewpoint than what happened in the individual, but

instructive, skirmishes. We began on a hillside looking north towards

Frederick, Maryland, where our leader, a well-respected, retired infantry colonel,

asked us what Lee was trying to do by moving towards Pennsylvania. My Army

counterpart, a SAMS graduate who has thought about these things at length,

responded, "The terrain in the valley was a natural funnel for Lee to take the

ground ahead of him and move into the North." I looked at the terrain, thought

of the geography, remembered my very slight skimming of Landscape Turned Red

and said, "Didn't Lee really want to get across Maryland into Pennsylvania to

gain access to the industrial capacity of the North and possibly show the

European allies that the Confederacy was for real?" Right or wrong, what struck

me was that I saw "terrain" across a broader distance like you'd see from the

air and my Army counterpart's view was shaped by infantry experience of being

on foot. It was the sharing of two diverse viewpoints that created a broader

view of what Lee was trying to accomplish.

Similarly, Ricks's most successful examples in The Generals used contributions of

diverse thinking airmen to strengthen the fight. General George Marshall's

embrace of the yet-unproven Army Air Corps and faith in its leader, General

Henry "Hap" Arnold, to strengthen the independent Army Air Forces early in

World War II is proof alone of the need for a broader viewpoint towards

warfighting. Marshall's

trust in Hap Arnold to grow the AAF to a robust,

independent fighting organization, sometimes at the expense of ground force

priorities, was critical to military success. Just as highlighted by Ricks, it

is Marshall's superior leadership that many look to for a superior example of

how a strategic leader should lead. Marshall's leadership skill is solidified

by the fact that all his ground Army subordinates in both theaters embraced the

contributions of airpower.

In Europe, Eisenhower clearly understood the

use of airpower to change the situation on the ground. Eisenhower had

significant trust in RAF Air Marshall Arthur Tedder and AAF commander in Europe

General Carl Spaatz. Tedder

was Eisenhower's second in command for the invasion of Normandy.

Spaatz

was "Eisenhower's Airman" as he commanded United States Strategic Air Forces in

Europe. Eisenhower understood the integration of

ground and air forces so well that when it came to establishing his

headquarters in England, he co-located his with Spaatz. Eisenhower rated Spaatz

and General Omar Bradley as the two leaders who did the most to defeat the Germans,

specifically describing Spaatz as an "Experienced and able air leader: loyal

and cooperative; modest and selfless; always reliable." A final testimony of

this trust is in what Eisenhower wrote to Spaatz in 1948: "No man can justly

claim a greater share than you in the attainment of victory in Europe." General

Omar Bradley, when asked by Eisenhower to rank top generals in prioritized

order based on their contribution to the defeat of Germany, listed Spaatz as

number two and General Elwood R. "Pete" Quesada as number four. Two in the top

five were airmen. (Bedell-Smith was one, Courtney Hodges was another, and

Patton didn't make the top five.)

In the Pacific, General Douglas McArthur's

relationship with General

George Kenney is one of the more interesting stories of how

an innovative air leader changed the way we fought on the ground during World

War II. Kenney's

ability to integrate both air and ground fighting to hop through the southwest

Pacific is what MacArthur's success was built on.

From innovative new bombing techniques to airdrop methods using bombers and

cargo aircraft to cutting trucks in half to move them into the fight, at every

turn Kenney used his unique experience and perspective to strengthen the fight

on the ground. MacArthur's own words about Kenney are the most descriptive of

what he contributed: "Of all the commanders in the war, none surpassed him in

those three great essentials of successful combat leadership: aggressive

vision, mastery over air tactics and strategy, and the ability to exact the

maximum in fighting qualities from both men and equipment." It is clear that

Kenney had MacArthur's trust to use his unique viewpoint on how to fight to

achieve military victory.

Numerous examples exist and all become clear in

a recently released volume of biographies titled Air Commanders.

This book's detailed descriptions of air commanders in conflicts ranging from

World War II to Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom highlight the role played

by airmen and the contributions of airpower to these conflicts. The unique perspective

provided by these air leaders to achieve military effects differently than what

would have been achieved by fighting through a single-service lens is a

critical lesson for future commanders. Each example is stronger or weaker based

on the teamwork between the ground commander and the air commander. Our most

successful military operations tend to have leaders that understood fighting in

the air as strengthening the fight and not as threatening to the Army as they

increasingly have since the early 1950s. A couple of the less lauded Army

leaders in The Generals begin to

exhibit fear of airpower during the Korean War. Maj. Gen. Ned Almond was

opposed to the Air Force's concept for conducting air operations and Gen. Mark

Clark advocated that tactical air forces should operate purely under the

command of the ground commander. In both cases, airpower's flexibility was not

embraced and may have limited airminded solutions for fighting in Korea. Just

look to one of the heroes of The Generals

for what a dose of airmindedness can achieve -- General O.P. Smith's first

action during fighting at the Chosin Reservoir was to build a runway.

Services don't fight wars, the nation does. The

nation fights wars by the application of the full capabilities of joint force to

achieve a military outcome. Ground combat should not be the goal of military

leaders when they develop plans, in fact it might be argued that we should

fight in a way that makes forces on the ground engaging the enemy a last

resort. By discussing generalship and its effectiveness purely in terms of the

Army, it discounts the strength of the joint team and what our nation expects

and deserves. Our nation invests heavily in building a trained joint force that

integrates diverse warfighting perspectives across the spectrum of military

operations. Using examples from one service viewpoint, without recognizing

joint teamwork, is half the story and does not strengthen future leaders with

examples of leadership that truly strengthens how we fight today. As we

continue toward a smaller, more capable, more adaptable military for the United

States, leadership examples with unique perspectives, teamwork, and, most

importantly, trust are increasingly important and should be emphasized.

Lt.

Col. Tom Cooper is deployed from Headquarters Air Force to the Office of

Security Cooperation -- Iraq, where he works to build more than just one strong

Air Force.

March 29, 2013

An insurgent’s memoirs -- and his observations about his British captors

I've long wanted to

know more about what the Iraq war looked like from the side of the insurgents.

I actually had hoped one day to write a book about this in collaboration with Anthony Shadid,

but he was killed about 13 months ago while trying to cover the fighting in

Syria.

But I got a bit of

insight, unexpectedly, when reading Ernie O' Malley's

On Another Man's Wound: A Personal

History of Ireland's War of Independence, which was

recommended recently by one of this blog's guest

columnists. (I didn't know when I learned that the book and

his other memoir were the basis for the great film The Wind That Shakes the Barley.)

Here is O'Malley's

net assessment of the war. It sounds kind of familiar, no?

The enemy could have

regular meals, a standard of comfort, the advantage of numbers and training,

more than ample supplies of ammunition, and well-cared-for and efficient

weapons, but they were...operating in a hostile countryside when they left the

shelter of their barracks....The British could defeat some of our columns and

round-up our men, but they could not maintain civil administration when they

had lost the support of the people.

Tom again: O'Malley

found that the British army, though full of veterans of World War I, was slow

to adjust to the situation in the Irish fighting, where the rebels could move

among the people. "Few [British] might be elastic enough for guerrilla

fighting," he concluded. He detected in the British soldiers "a glum, swarthy

melancholy."

As a captive, he

concluded that, "Soldiers make bad gaolers," or jailers. He eventually escaped.

The British never even figured out his true identity, even though they beat him

and threatened to torture him with a red-hot poker, holding it close enough to

his face to burn his eyebrows and singe his eyeballs. Calling Abu Ghraib!

What did victory look

like? One day early in 1921, the fact that the fence-sitters were coming over

to the side of the rebels made O'Malley realize he was winning: "We were

becoming almost popular. Respectable people were beginning to crawl into us;

neutrals and those who thought they had best come over were changing from

indifference or hostility to a painful acceptance."

One important

difference, though I don't know quite what to make of it: The British soldiers

and their Irish foes were much closer culturally than were the Americans and

Iraqi insurgents. They could even speak to each other, which meant that

O'Malley could sort of apologize to some British officers

held prisoner before executing them. O'Malley's brother had even been in the

British army.

Gen. Hodges vs. Gen. Barno: Is the Army losing too many talented officers?

What General Hodges lacks in facts in his

column he makes up in indignation. Dare General David Barno worry that the Army is

losing talented Army officers? "What an insult to the thousands who are in fact

staying," Hodges fumes.

Is the Army

"somehow non-adaptive, too inflexible and unimaginative"? Well, I would say too

many Army generals are. But, without

any facts to back up his case, and conveniently ignoring years of

inadaptiveness in Iraq (2003-06), General Hodges assures us that, "This is

nonsense and I reject it." He offers no facts, but hey, we have to take it on

faith, he seems to say -- after all, how could a system that produces me be faulty? It reminds me of the old

Ring Lardner line: "‘Shut up,' he explained."

But you all

know what Tom thinks -- I wrote a whole book on the subject. I

would like to know what you all think, especially junior officers, both those

leaving and those staying in. Let's ask those involved. Who is right: Hodges or

Barno?

Necessary

disclosure: Barno is a colleague of mine at CNAS.

Rebecca’s War Dog of the Week: 20 years later, the world has not forgotten India’s bomb-sniffing dog, Zanjeer

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

When a series of 12 bombings rocked Mumbai in March 1993 -- blasts

that killed over 250 people and left more than 700 others injured -- one member

of India's Bomb Detection and Disposal Squad (BDDS) was heralded as savior, a golden

lab called Zanjeer. And now, two decades later, Zanjeer's photo and his story

are making the Internet rounds once again, this time in memorandum.

Zanjeer's first find during those fateful days came on March

15, when he gave his signature three-bark alert on a bomb-laden scooter parked

on Dhanji Street, a mere "stone's throw away" from BDDS

headquarters. In the days that followed he reportedly saved thousands more

lives by finding explosives in "unclaimed suitcases" discovered at the Siddhivinayak

temple and then again a few days later at the Zaveri Bazaar.

All in all, Zanjeer helped members of the BDDS find, as reported by Reuters, "more

than 3,329 kgs of the explosive RDX, 600 detonators, 249 hand grenades and 6406

rounds of live ammunition."

Zanjeer, named after a 1973 Hindi action film about a lone honest cop

who perseveres in a world overrun by corruption, was trained in Pune and joined

the officers of India's BDDS in 1992 at just one years old. The much beloved

and lauded dog went on to have an illustrious and astoundingly productive

eight-year career, during which he was credited with uncovering: "11 military

bombs, 57 country-made bombs, 175 petrol bombs, and 600 detonators." These

finds coming after the March bombings

in 1993.

When Zanjeer died

of bone cancer (other reports

say lung failure) in November of 2000, his fellow officers gave him full honors

during a ceremony and memorial service -- as seen in this

photo as a senior official places flowers over Zanjeer's body. And while

the world is remembering this dog 20 years later, citizens of Mumbai are said

to have commemorated the anniversary of Zanjeer's death yearly.

According to Zanjeer's obituary,

"The cops grew so dependent on Zanjeer that there were occasions when they

would bring only Zanjeer and no equipment." The chief of BDDS

during Zanjeer's tenure, Nandkumar Choughule, said

that the dog was "god sent" and that when men were not able to track down the

explosives, it was Zanjeer who found them.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers