Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 121

March 14, 2013

The FP transcript (IV): Why is making the hard choices always someone else’s job?

[Here are Parts I,

II,

and III.]

Ricks: Michèle?

Flournoy: Two

things, and especially because I think in Iraq, because the fundamental premise

for the war was shown to be false, that should have triggered exactly the kind

of discussion that: "Uh-oh, here we are. We've discovered there are no

WMD, so what are we trying to do here, and what is our strategy and what are

the risks and what are the tradeoffs and how much in resources are we willing

to put in?" And then, the perverse effect is that it also affected

Afghanistan because once the focus was on Iraq, Afghanistan really did become

an economy-of-force effort for the first many years, which also takes the

oxygen out of the fundamental strategic discussion.

Fastabend: I

discovered this dilemma in Iraq. I wasn't in charge of strategy; I was in

charge of operations. From the strategy guys, I would get the strategic

conditions I was supposed to achieve: "Secure the borders of Iraq; end the

violence. Our job is done. Make it happen." And no choices had been made,

no options, nothing really was useful with respect to strategy.

Ricks: Shawn and

Michèle, you both effectively held strategic positions. In fact, Shawn had the

title, director of strategy for the American Empire.

Glasser: That's a

capital "E"?

Ricks: Again and

again we're coming back to original sin, fruit of the poisoned tree, and

strategic confusion at the outset, where the system did not work, where the

differences were not examined, and where assumptions were not examined either.

Brimley:

Right, so I think we have a profound inability to make hard, clear strategic

choices, but then I think that forces us to react, right? It forces us into a

reactive posture. And for years I've heard the phrase, "Oh, Shawn, you

know the enemy has a vote. The enemy has a vote." But we have a veto,

right? And as we think about the years ahead, as we think about a constrained

fiscal environment, we're going to have to make hard choices. And the enemy is

going to try to lure us to do things that are not in our comparative advantage,

so we're going to have to face up to the notion that we can veto that. We have

a choice, and that's in how we prosecute these things. Those choices carry

inherent levels of risk, but we should embrace that, not run from it.

Ricks: Michèle,

why doesn't the system make hard choices?

Flournoy: Well, I

can speak to what I experienced in the Obama administration. A lot of what

we're talking about here happened in a much earlier period. I'm just guessing,

I'm speculating, that part of why this initial fundamental strategic rethink

didn't happen in Iraq is that, in the middle of [the war], you've gone in and

you've broken the china, and now you have to say, "Whoops. The fundamental

premise was wrong. Now what are we going to do?"

That's a very politically fraught thing for an

administration to do when it's got tens of thousands of Americans in harm's way

on the ground for a mission that was very controversial from the beginning. I

think it would have been an extraordinary act of leadership for, whether it was

the president or the national security advisor, you know, the team, to sort of

say, "Hey, wait a minute. This is not what we thought it was. What are our

interests? How do we clearly define a new set of objectives and make some

choices about how we're going to prosecute this?"

Ricks: That

explains Iraq, but does it explain Afghanistan?

Flournoy: In

Afghanistan -- again, I wasn't there in the early days-- I think that we were

very good at getting in, very poor at seeing the way out. And I think part of

the reason why we migrated from the focus on al Qaeda to "What are we

going to do about Afghanistan writ large?" is getting caught in the sense

of: What is a sustainable outcome? If you take too narrow an approach, it's

like taking your hand out of the water. Once you leave, you're right back in

the exact same situation where you have a government that's providing safe

haven and you're facing a threat again. And yet we never really resourced,

fully resourced, a counterinsurgency strategy until very late in the game when

Obama did the review. But that was like coming in the middle -- the symphony

had been playing for a number of years. You're inheriting something and now

trying to say, "Well, now, given the interests at stake, clearly define

who is the enemy, who is not. What's the limited outcome we're going to try to

achieve, and how do we go after that?" But it's a lot harder to do coming

into the middle of an operation with a lot of history than it is to do it right

from the beginning. And I think that we probably would have defined it

differently had we had that opportunity to shape it from the beginning, but

given where we were and what we inherited, I think, you know, we did the best

we could.

Ricks: Jim, it

seems to me that what this conversation is saying is that there's something

profoundly wrong at the civil-military interface, and your initial question

speaks to this.

Dubik: The sense

that I'm getting is we spend too much time worried about control and autonomy

and less time talking about shared responsibility in strategic and operational

decisions. The civil-military discourse is defined by civilian control of the

military -- absolutely essential to it -- but all relationships are more

complex than one formula can ever describe. So, while control and autonomy are

part of the relationship, the shared responsibility is a huge part that doesn't

seem to get as much play in the professional military education or in the

development processes that are used for producing civilian strategists and

leaders.

Ricks: This is an

unfair question, but let me ask it anyway. If you could rewind us to Sept. 11,

2001, how should civil-military discourse have been conducted at that point?

Dubik: Well it

certainly should have been centered around the fundamental questions, not of how, but of why and what.

But I'd like to kind of challenge the discussion a little

bit, in the sense that we didn't have these analyses. When I went back and

reviewed your

books [gestures at Ricks], Woodward's

books, Michael

Gordon's book, your

book [gestures at Chandrasekaran], I see a very similar pattern with

respect to Iraq for sure. There are at least eight or nine major strategic

reviews that clearly identified that what we were doing was not working. Yet we

didn't make really a big shift until 2007. My bet is you could go through and

find papers about Afghanistan that say the same thing, that until you [gestures

to Flournoy] did the review in 2009, that there were plenty of evidence that

what we were doing wasn't working, but we had no shift. Back to your original

question. The first question was more about how and not enough about why and

what, and then we couldn't adapt. It wasn't just in Afghanistan that we were

treating it as an economy of force -- we were -- but it was an economy of thought. There wasn't the attention.

Flournoy: Because

there's no bandwidth.

Dubik: Right.

Brimley: There's

only so much bandwidth for policymakers, and what you see early in Afghanistan

is all the planning power on the military and civilian side gets sucked into

the Iraq problem. And it is sort of on autopilot: Things are going well;

there's not a lot of thought that needs to be given to it.

Ricks: Bandwidth?

When I go back and read the papers of George Marshall and other senior leaders

in 1939, 1940, '41, they're dealing with much bigger problems, global issues,

and they are making really hard

choices, such as: Let the Philippines go, keep the sea lines of communication

open to Australia--but win in Europe first. These are basic, fundamental

things.

So I would argue with the bandwidth thing. What's clogging

them up nowadays?

Crist: The

initial question I raised was: Do commanders have to think? And I think it gets

to what General Dubik said about getting focused on shooting the close-in

target.

We don't think about the long-term ramifications of the

actions and the strategy. In my view, the great failing of Tommy Franks, he never

asked about that the assumptions were coming down about what this campaign

would look like -- assumptions being facts in the campaign design. Those

assumptions were never challenged. In many ways, as I describe in my

book, there was no red team to look at, "OK, how is this going to

impact Iran? Does it open opportunities for them, or does it have a deterrent

effect?" And so I think that, having sat down with a number of top

commanders and staff, that piece of it isn't done. It's almost discouraged

because "that's the policymakers' realm, it's not ours."

Dubik: Well

that's the civil-military issue. It's control and autonomy. So, at least on the

military side, the bulk of the training is deductive training. You are given a

mission, you are given an end state, you are tossed over the transom the

strategy, and just. . . .

Ricks: When

you're talking about shared responsibilities, it seems to me you're talking

about trust. Trust is the essence of that shared responsibility -- the sense of

a common future, that we trust each other, we'll be working on this. It seems

to me you're saying there's a fundamental lack of trust in our civil-military

system.

Mudd: Hold on.

One interjection that relates to bandwidth is the difference between choices

and questions. I think [back in 2001] we blew over the questions. You said it's

not "how," which is what we did on Sept. 12; it's why and what. On Sept. 12, 2001, can you imagine asking the question: Is

the Taliban really a threat? Today, 12 years later, I'd say, "Well

clearly it's not a threat! In fact, they're going to be in the government!" But

we blew through the question, which led to space, because you have to have

space because the Taliban's a problem -- in retrospect, they weren't. So we

made a choice, but we didn't know we had a choice.

I'll close by saying there's a bandwidth issue; part of this

is the speed of decision-making in Washington. Can you imagine at the Washington Post, sitting back on Sept.

12 and saying, "Wait a minute; you sure the Taliban's a threat?" You

would have been crushed. That, clearly, would have been a good question.

Ricks: I want to

go to two things here. Dave Fastabend, you talk about the inability to make hard

choices. How do we get the system to surface and make hard choices?

Fastabend: I

think we need to relook at what we teach about strategy and train people about

how these decisions are made. I think we should teach strategy much like the

Harvard Business School teaches strategic decision-making in business, on a

case-study basis. There's lots of good history out there where they could teach

people what were, in essence, the choices people had in various situations. You

[Ricks] very articulately described the ones Marshall had. Talk about what the

options were, how they made the trades and came to it. But don't take people

through these ridiculous exercises about define the ends you want and go see if

someone can make a path to it.

(and more yet to come)

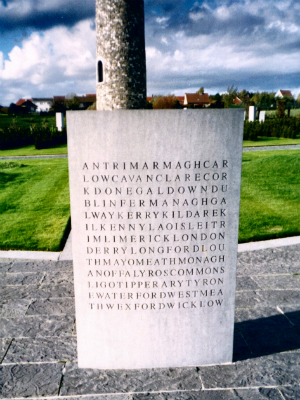

The British Army and the people of Ireland: This is one complex love story

By

Henry Farrell

Best

Defense office of ethno-military affairs

You

asked recently whether the

"British Army ever formally

recognized and honored the role that Irishmen (not Anglo-Irish aristos)

historically played in its enlisted ranks?"

The answer is yes, at least for World War I. Neither the British nor the Irish

government was particularly inclined to celebrate the role of Irish soldiers in

the British Army until quite recently. World War I split the Irish Volunteers

into a majority under the sway of John Redmond, who supported the British in

World War I (and in many cases volunteered to join the British Army), and a

minority who opposed the war and the threat of conscription (which was

nominally led by my great-grandfather Eoin MacNeill). The latter started the

Easter Rising and the War of Independence, and won, more or less (the Irish

civil war was fought between two sub-factions of this faction; as Brendan Behan

once remarked, the first item on the agenda of any IRA meeting was always The

Split). The former nearly completely disappeared from historical memory --

nobody, except the Ulster Unionists, particularly wanted to remember the

Irishmen who had fought on Britain's side. Sebastian Barry's extraordinary

play, The Steward of

Christendom, talks to this amnesia from the

perspective of the "Castle Catholics" who had sided with the British

administration. Frank McGuinness's earlier play, Observe the

Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, talks about it from a Unionist perspective.

This began to change in the 1990s,

leading to an initiative to create a memorial to the Irish who died in World

War I, which was folded into the more general peace initiative. The result was

the building of a tower with financial support from both the British and Irish

governments, commemorating the war dead from both parts of Ireland. The British

and Irish army bands played together for the first time at its opening. The

Wikipedia page on the memorial gives a good overview of the project and the politics behind it.

Henry

Farrell

is an associate professor of political science

and international affairs at the George Washington University. He blogs at the

Monkey Cage

and

Crooked Timber

.

The other rebalance

By Lt. Cdr. David

Forman, US Navy

Best Defense guest

correspondent

Before President Obama's national security team started

their analysis in 2009 that eventually led to the current rebalance

to the Asia-Pacific, then-Senator Jim Webb experienced a peculiar event. It was

so peculiar that it now helps shape his argument that we need another type of

rebalance: one that returns the legislative and executive branches to actual co-equal partners in government.

In December of 2008, Sen. Webb entered a soundproof room to

review the Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA) that would shape our long-term

relations with Iraq. Though not actually classified, the White House controlled

the document as though it was. According to the logbook he signed to enter the

room, Sen. Webb was the first member of the legislative branch to review it. The

irony of "secretly" reviewing a document that should have been written or

thoroughly debated by Congress was not lost on such an experienced public

servant.

In his recent article,

"Congressional Abdication," in The

National Interest, Webb draws attention to three main events he believes

indicate Congress is not fulfilling the full range of its responsibilities,

including Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution

as it pertains to use of the military. First, as mentioned above, the Congress

did not play any meaningful role in the development of the SFA agreement with Iraq. Though not an official

treaty, the agreement was a unique display of exclusive executive-branch

negotiations. Second, and most alarming to Webb, is that the Congress played no

part in debating or approving combat operations in Libya in March 2011, a

previously unprecedented type of military intervention. And last, the Congress was

kept in the dark until the president was ready to sign the strategic

partnership agreement with Afghanistan in May 2012.

To be clear, Webb's remarks at a recent session at the

officers of The National Interest

began with, "I'm not on a crusade." He is not trying to throw stones in the

Congressional arena now that he is on the sidelines. Webb's goal is to provide

an honest and insightful assessment of the current imbalance between the two

branches.

After the terrorist attacks on U.S. soil in 2001, the president

was understandably afforded great leeway to act. No elected official wanted to

be seen as unpatriotic in the aftermath of such a penetrating and deadly

assault on American territory. However, the complexity and diversity of

pursuant foreign policy issues combined with the perpetual need to fundraise

has prevented Congress from digging deep into foreign policy issues and

recovering the ground it patriotically sacrificed in 2001.

The path to rebalancing is not easy or entirely clear, but

recognition by the president and the Congress, the media, and the American

people is a necessary first step. Congressional approval may seem like a

nuisance in the pace of today's political developments, but it is also vitally

important. Not only does this process adhere to our laws, it also shows the

resolve of the American government and the nation it represents.

Though the eventual solution will take time, the Senate

Foreign Relations Committee is a natural focal point to help restore

legislative balance to executive branch involvement in foreign policy. The

framework for Congressional involvement and genuine oversight still exists, but

its members must duly exercise this capability. With American involvement in

Afghanistan winding down, issues with North Korea and Iran are most likely

front-runners of opportunity for the Congress to reassert its constitutional

authorities and work as a co-equal partner to steer our nation through a myriad

of upcoming foreign-policy decisions.

LCDR David Forman, USN

, is

a senior military fellow at the

Center for a New American Security

. The

views presented here are his own and do not represent those of the Navy or the

Department of Defense.

March 13, 2013

Navy captain: Time to deep-six the old school manned aviation carrier -- before long-range Chinese missiles do it for us

Navy Capt. Henry Hendrix has just written one of the best

papers I've seen in the last several years by an

active duty officer. In it, he challenges some of the central beliefs of his

service. "After 100 years, the [aircraft] carrier is rapidly approaching the

end of its useful life," he asserts.

Hendrix,

the current

director of naval history, says the current aircraft carrier is

too expensive, inefficient, and of doubtful survivability. It is now in danger

of becoming, like the battleship during the mid-20th century, "surprisingly

irrelevant to the conflicts of the time."

"If the fleet were designed today," he

observes, "it likely would look very different from the way it actually looks

now -- and from what the United States is planning to buy."

He would like to see unmanned combat aerial

vehicles, more than mere drones, capable of flying off both big carriers and

the smaller "amphibious" carriers.

What would the equivalent of this paper be in

the Army? Has it been written? Any smart colonels out there challenging sacred

cows?

The FP transcript (III): How did we back into the strategies we used, and why?

Crist: I agree on

the notion of the tendency of the U.S. military. In Vietnam, they used to call

it the "Little Brown Man Syndrome," which is: The Americans come in

and show you how to really fight your war. But I think with Afghanistan the

fundamental problem is a lack of a long-term strategy. What do we want

Afghanistan to do? And I see we sort of evolved into it without a lot of

thinking.

The initial force went in; we got enamored with the idea of

SOF [special operations forces], light footprint, using the Northern Alliance

-- in fact we probably should have had more conventional forces. We missed a

lot of opportunities as these guys skirted across Pakistan, and we, frankly,

allowed them to do it because the Afghans wouldn't go after them. If they wanted

to sit up in the hills, the Northern Alliance was more than happy to let them

sit in the mountains, and we didn't have that capability.

Then the problem is, as we slowly evolve with, frankly, not

a lot of thought -- if you look at the force incrementally increasing, it's not

a well-articulated strategy. Then it comes to the point where, well, we have

the force, we need to start doing this ourselves, and we sort of fall back on

our natural patterns and tendencies and things that are comfortable with an

effective military that likes to solve problems. So I lay it on the long-term

strategy that went in in 2001.

Jabouri: Let me

say something from my experience: I think American forces focus just on the

enemy, on al Qaeda, and they forget about the people.

I think if you want to win the war against al Qaeda, you

should protect the people first. The American forces always, in the beginning,

in Iraq, they put their eyes on al Qaeda, and they don't care about the people.

I think the security forces can't create the security without the long-term

forces. If you now go to Kurdistan in Iraq, if you see the images, Kurdistan

has very good security, but they do not have many checkpoints or forces. The

people have, and the government has the security forces to keep the security.

They are the people in other parts of Iraq, the people not interested in the

security forces of Iraq because they do not have to create the security.

Ricks: This seems

to go to Phil Mudd's question of space versus targeting, but it seems to me

also to Colonel Alford's comments because one of the answers to reconciling

space and targeting is to have local forces occupy the space, not American

forces that alienate locals.

Dubik: But a

strategy, correctly or not, a strategy that emphasizes local forces, building

local conditions, is de facto a long-term strategy. It gets right back to the

question of -- we backed into both these wars.

Ricks: Not unlike

in Vietnam, where we put in ground troops originally to protect the air bases.

Dubik: And it

sucked us in. We just backed ourselves into the problem we faced, and had we

thought that the solution was going to be a 10- or 15-year solution, we

certainly would not have committed. We would have changed many of the decisions

that we made, but we didn't adopt the indigenous force because we thought we

could solve it and leave.

Fastabend: I

think the reason we do that consistently is, as I hinted at in my question (I

really liked your question; I'll explain to you why), is because we think

strategy and we keep strategy, and our theory of strategy is the linkage of

ends, ways, and means, which is how I got here, which is how I'll do my job

tomorrow.

It is pablum; it is a way to avoid making a real choice, so

no one in or out of the government ever said to themselves, "Let's decide

what we're going to do. Are we going to target individuals regardless of space,

or are we going to go in there and have space?" No, what we said is,

"We need a stable government in Iraq, so therefore, you need a stable

government in Iraq." Deductive logic tells you that you need to control

everywhere in Iraq. And then you have to worry about the security forces;

you've got to make sure they've got border patrols. And we never went back to

the fundamental choice about what do we really need to do. We hide choices. We

never talk about choices because choices are hard and choices mean making a

decision. Choices mean taking responsibility for who makes the choice and which

choice they take -- and that, in my view, is the biggest flaw we have

institutionally in this country, is we've got very shallow theory and doctrine

about what strategy really is.

Ricks: This is a

great comment.

(Much more to come)

Army force structure in World War II

I bet there is a good

blog post in this chart of the Army of World War II, if

I could only understand it.

If you are in a

hurry, here is the official answer.

March 12, 2013

Remember my 'More Salvadors, Fewer Vietnams'?: Turns out it's already written!

Remember how last month I was thinking aloud

about how I should write an essay on future force structure with the title "More

Salvadors, Fewer Vietnams"? Well, it turns out it already has

been written, by Army Maj. Fernando

Lujan. It was published last week.

Maj. Lujan, a career Special Forces officer who

extensively studied the operations of American forces in Afghanistan, and also

spent a lot of time hacking his way through the jungles of South America,

called it "Light

Footprints: The Future of American Military Intervention."

And it is a fine article about military human capital. The essay, he said at a

seminar I attended last week, "is about how to do more with less." Not only is

the light footprint, indirect approach more effective than sending in brigades

of conventional ground forces, it also is cheaper, he argues.

There are several characteristics of successful

missions, he explains:

They are led

by civilians, which plugs them into the larger political strategy. "Without

a robust political plan, military action may only postpone state failure or

prolong the conflict."

They are small.

"It's hard to be arrogant when you're outnumbered," he quotes an SF officer as

saying.

They are indirect,

"working by, with, and through the indigenous forces that can preserve peace in

the future."

They are consciously long-term. "An overly aggressive pace can inadvertently cause

advisers to ‘mirror image' Western methods and organizational structures onto

local forces rather than taking the time to understand the unique historical

and cultural context of the country first. Unless indigenous forces see the new

methods as organic ... they are likely to jettison them as soon as foreign

advisers withdraw."

They are preventive.

"They are generally intended to prevent and contain security problems, not to

resolve them decisively."

Special operations, he reminded us at the

seminar, is "not just drone strikes and ninjas." Word up.

The 'Foreign Policy' roundtable (II): What we should have done in Iraq and A'stan

Ricks: What I

hear from around

this table is a remarkable, surprising consensus to me. I'm not hearing any

tactical problems, any issues about training, about the quality of our forces.

Instead, again and again what I'm hearing is problems at the

strategic level, especially problems of the strategic process. To sum up the

questions, they are asking: Do our military and civilian leaders know what they

are doing? And that goes to the process issues and to general strategic

thinking. That's one bundle of questions. The second emphasis I'm hearing, and

this also kind of surprised me, is, should we have, from the get-go, focused on

indigenous forces rather than injecting large conventional forces? That is, in

Iraq and Afghanistan, have we tried to do El Salvador, but wound up instead doing

Vietnam in both, to a degree?

Mudd: Just one

quick comment on that as a non-military person: It seems to me there's an

interesting contrast here between target and space. That is: Do we hold space

and do we help other people help us hold space, or do we simply focus on a

target that's not very space-specific? And I think at some point fairly early

on we transitioned there [from target to space], which is why I asked my

initial question. A lot of the comments I hear are about the problem of holding

space, and should we have had someone else do it for us? And I wonder why we

ever got into that game.

Ricks: Into which

game?

Mudd: Into the

game of holding space as opposed to

eliminating a target that doesn't

really itself hold space.

Alford: It's our

natural tendency as an army to do that. To answer another question, it's also

our natural tendency as an army to build an army that looks like us, which is

the exact opposite of what we should do. They're not used to our culture. One

quick example, if I could: the Afghan border police. The border police, we

tried to turn them into, essentially, like our border police and customs

agents. Right across the border, the Pakistani Army uses frontier guardsmen.

Why do they do that? They use their culture -- a man with a gun that fights in

the mountains is a warrior. He's respected by his people. He's manly. All those

things matter, and it draws men to that organization. We always talk about how

our borders on [the Afghan] side are so porous; it's because we don't have a

manly force that wants to go up into the mountains and kill bad guys, because

we didn't use their culture.

Ricks: So we're

already breaking new ground here. We're holding up the Pakistanis as a model!

Alford: On that piece. It's a cultural thing.

Dubik: I agree

with the second comment. On the first point, in terms of why we held space, I

think it's how we defined the problem. We defined the problem not as al Qaeda

-- it was "al Qaeda and those who give them sanctuary." And so we couldn't conceive

of a way to get at al Qaeda without taking the Taliban down, and because of the

problem definition, we inherited a country.

Ricks: So what

you're saying is actually that these two problems I laid out come together in

the initial strategic decision framing of the problem.

Fastabend: I

don't think there was such framing.

Ricks: The

initial lack of framing...

Fastabend:

Getting back to Ms. Cash, we didn't really decide what the questions were. We thought we knew

the question. You know, we thought we had in each case [of Afghanistan and

Iraq] governments to support that would hold space, and that was a secondary

thing that came on us when we got there: that actually the sovereign government

wasn't so sovereign.

Ricks: I just

want to throw in the question that [British] Lt. Gen. Sir Graeme Lamb sent. He

couldn't be here today. General Lamb said, "My question is, given the

direction I had -‘remove the Taliban, mortally wound al Qaeda, and bring its

leadership to account' -- who came up with the neat idea of rebuilding

Afghanistan?"

Mudd: It's

interesting. If you define threat as capability and intent to strike us, then I

think there's confusion early on with the Taliban, because I would say they had

neither the capability nor intent to strike us, but they provide safe haven. If

you look at areas where we have entities that have those twin capabilities or

those twin strengths -- Yemen and Somalia come to mind, maybe northern Mali --

we're able to eliminate threat without dealing with geography. So there are

examples where you can say, "Well, we faced a fundamental -- I mean, not

as big a problem as Afghanistan." But you look at how threat has changed

in just the past two years, and I don't think anyone would say that the threat,

in terms of capability and intent, of Shabab or al Qaeda in the Arabian

Peninsula, is anywhere near where it was a few years ago. That's because we

focused on target, not geography.

Glasser: Just to

go back to this question, was the original sin, if you will, focusing on U.S.

and NATO presence in Afghanistan, versus working from the beginning to create

or shore up local forces? I want to probe into that a little bit. How much did

people at the time understand that as a challenge? I remember being in Kabul

for the graduation of the first U.S.-trained contingent of Afghan army forces,

and they were Afghan army forces. These guys worked for warlords that had come

together, Northern Alliance warlords who made up the fabric of the Defense

Ministry. They had nothing to do with an Afghan force, and that's why we're

still training them now.

Ricks: But

Colonel Alford's point is that, those are the guys you want to work with,

though. But don't work with them on your terms; work with them on their terms.

Glasser: But

that's what we did. That's what we do. We worked with the warlords in

Afghanistan. That's who our partners were in toppling the Taliban.

Alford: But we

never turned it over to them, though. In '04, I was [in Afghanistan] as a

battalion commander. We never would let them fight unless we always led the

way. It's part of our culture, too, as soldiers and Marines. You send an

infantry battalion into a fight, they're going to fight. It takes a lot to step

back and let the Afghans do it, and do it their way. Provide them the medevacs and

fire support -- that's the advisory role for those missions we're going to

switch to this spring, and I'm all for it. We should have done this four years

ago, but now we also need to see if this is going to work over the next almost

two years. We need to be ruthless with young lieutenant colonels and colonels

who want to get out there and fight, or generals who do, to support the Afghans

and then see how they do against the Taliban. I'll tell you how they're gonna

do: They're gonna whoop 'em. The Taliban does not have the capability to beat

the Afghan army if we get out of their way.

(more)

Headline of the day: 'War of 1812 enthusiasts gather in Hamilton'

Oh, Canada.

I guess the two of them shook hands.

March 11, 2013

The 'Foreign Policy' transcript (I): Our basic problem over the last 10 years has been decisionmaking at the top level

Here is the first part

of a transcript of a conversation held at the Washington offices of Foreign

Policy magazine in January of this year. A shorter version, with full IDs of the participants, appears in the current issue of

the magazine. This is the full deal, edited just slightly for clarity and ease

of reading, mainly by deleting repetitions and a couple of digressions into

jokes about the F-35 and such.

I had asked each

participant to bring one big question about the conduct of our wars in

Afghanistan and Iraq. I began. We began with those.

Thomas E. Ricks:

One of my favorite singers is Rosanne Cash, a country singer who is Johnny

Cash's daughter, who has a great line in one of her songs: "I‘m not looking for the answers-- just to

know the questions is good enough for me." And I think that is the

beginning of strategic wisdom: Rather than start with trying to figure out the

answers, start with a few good questions.

So what I'd like to start by doing is just go around the

table with a brief statement -- "I'm so-and-so, and here's my

question." So, to give you the example: I'm Tom Ricks, and my question is,

"Are we letting the military get away with the belief that it basically did the

best it could over the last 10 years in Iraq and Afghanistan, but that

civilians in the government screwed things up?"

Philip Mudd: I

guess my question is: "Why do we keep talking about Afghanistan when we went in

12 years ago, we talked about a target, al Qaeda. How did that conversation

separate?"

Maj. Gen. David

Fastabend (U.S. Army, ret.): My name is David Fastabend, and my question

is: "Do what we think, our theory and doctrine, about strategy -- is that

right? Could we not do a lot better?"

Rajiv Chandrasekaran:

Rajiv

Chandrasekaran, got a lot of questions. I suppose one among them would be,

"How did the execution of our civilian-military policies so badly divert on the

ground at a time, at least over the past couple of years, when there was supposed

to be a greater commonality of interests in Washington?"

Lt. Gen. James M.

Dubik (U.S. Army, ret.): I'm Jim Dubik, and my question's related to

Rajiv's and Tom's: "How do we conduct a civil-military discourse in a way that

increases the probability of more effective strategic integration in

decisions?"

Shawn Brimley:

Shawn Brimley. I have a lot of questions, but one that keeps coming to mind,

being halfway through Fred

Kaplan's book, is: "How did we,

collectively, screw up rotation policy so badly that we never provided our

military leaders the chance to fully understand the reality on the ground

before they had to rapidly transition to a new colonel, a new brigadier, a new

four-star?"

Maj. Gen. Najim Abed

al-Jabouri (Iraqi Air Force, ret.): My name is al-Jabouri. As an Iraqi, I

have a different view of 2003. I was a general in the Iraqi Air Force, so I

wanted to shoot down your airplanes. After 2003, I was a police chief and a

mayor, so I wanted your help to build my country. In the last 10 years I have

learned that America has a great military power. It can target and destroy

almost anything.

However, I have also learned that it is very difficult for

America to clean up a mess it makes. Leaving a mess in someone else's country

can cause more problems than you had at the beginning. Military operations in

Muslim countries are like working with glass. If you do it right, it can be

beautiful and great, but if you break it, it is difficult to repair or replace.

My question is: "Do American strategy planners understand the consequences of

breaking the glass, and if so, do they know what it will take to repair or

replace the broken glass?" Thank you.

Col. J.D. Alford, USMC: My name is Dale

Alford. I too have many questions, I guess, but I'm going to stay a little

bit in my lane and I'm going to talk about the military. My question would be:

"Can a foreign army, particularly with a vastly different culture, be a

successful counterinsurgent? And if not, why haven't we switched and put more

focus on the Afghan security forces?"

David Crist: My

name is David

Crist, and a bunch of people had very similar lines of thought to what I

was going to use, so I'll take a common complaint that James

Mattis says all the time and frame that into a question: "Do our commanders

have time to think? Think about the issues and the information -- in some ways

they have to be their own action officer. Do they have time to sit back and

think about the issues with the op tempo going on and just the information

flow?"

Michèle Flournoy:

I have two, and I can't decide which one.

Ricks: You get

both.

Flournoy: I get a

twofer? So the very broad, strategic question is: "How do we ensure that we

have a political strategy that takes advantage of the security and space that a

military effort in counterinsurgency can create? How do we ensure that the

focus remains primarily there while we resource that aspect?" Kind of a

Clausewitzian question.

Second is a much more narrow question, and we have the right

people in the room to reflect on this, which is: "What have we learned about

how to build indigenous security forces in a way that's effective and

sustainable?" I mean, this is a classic case where we reinvent the wheel, we

pretend like we've never done it before, we pretend like there aren't lessons

learned and good ways -- and less effective ways -- to do this. So: "Can we

capture what we know about how to build indigenous security forces?"

Susan B. Glasser:

I have a question of my own that's particularly for the people with a military

background in this room, which is: "In September 2001, if you had told us that

in 2013 we are going to be in Afghanistan with 65,000 American troops and

debating what we accomplished there and how quickly we can get out, how many

more years and how many billions of dollars we'd have to pay to sustain this

operation, my strong sense is that there would have been an overwhelming view

in the U.S. military -- and among the U.S. people more broadly -- that that was

an unacceptable outcome. So, if we can all agree that 13 years was not what we

wanted when we went into Afghanistan, what did we miss along the way?"

(more to come...)

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers