Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 118

March 28, 2013

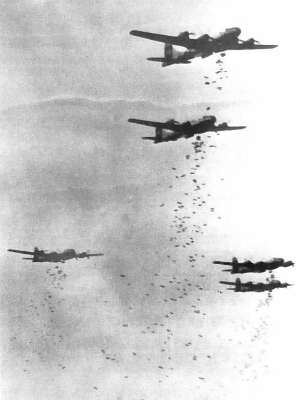

'Mission with LeMay': Perhaps the worst military memoir I've ever encountered

I recently picked up the

memoirs of General Curtis LeMay, partly out of guilt that I don't know more

about the history of the Air Force. My problem is, I still don't.

The book is mainly pablum. I gave

up about halfway through and skimmed the rest, something I rarely do.

I did learn a few things:

--Alamogordo, New Mexico, seems to

be the only Air Force base so lonely that even the chaplain once deserted.

--LeMay had a contempt for

professional military education typical of the fast-rising officers of World

War II. "It was utterly absurd, sending a lot of people to the War College

after the war, when they'd already been through the mill." I wonder if the

seeds of the Vietnam War are contained in that view -- that if you fought in

the big one, there was nothing more to learn?

--I didn't know that he actually

wrote that the solution to the Vietnam War was to threaten "to bomb them back

into the Stone Age." He did.

--He did seem to use mission

command, and see it as particularly American. "My notion has been that you can

explain why, and then you don't need to give any order at all. All you have to

do is get your big feet out of the way, and things will really happen. Forever

I took the same course. Get the team together. ‘There's the goal, people. Go

ahead.'"

That said, much of the rest of it is

the type of claptrap that H.L. Mencken made a living destroying. I had expected

that having Mackinlay Kantor, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Andersonville, as co-author of the

memoir was a recommendation. I didn't realize that Kantor was a hack.

So I would rate this memoir as even

worse than Douglas

MacArthur's, which at least gave the reader a strong sense of that

general's querulous grandiosity. And also worse than Tommy

Franks' book, which had some memorable passages that inadvertently revealed

that man's ignorance of his profession. (Plus, you can buy it used for one

penny.)

Army to 24,000 soldiers: Take a hike, bub

I've been reading a briefing by Maj. Gen. Richard P.

Mustion, commander of the Army's Human Resources Command, who predicts that

the Army will have to eject about 24,500 soldiers in the next five years. That

is, in order to reach the projected size of 490,000 in 2018, it will have to

lose 17,000 more enlisted soldiers than it would lose through natural rates of

attrition, and also 7,300 officers.

I hadn't seen those numbers before. Have youse?

I actually think the Army is going to have to lose more than

that, because I think the overall defense budget will be cut more than the Pentagon

expects. If that happens, I hope the Army aims to maintain quality more than

quantity.

March 27, 2013

The Best Defense interview: Steve Coll on White House leaks & what might happen

Steve

Coll, a former managing editor of the Washington

Post and author of Ghost Wars, a favorite book of many readers of this blog, is one of the best

journalists I've ever met. He especially understands intelligence matters,

national security, and Washington. So when he wrote this week in the New Yorker about the possibility of

high-level indictments of national security officials at the Obama White House,

I paid attention. Here is an e-mail interview I

conducted with him:

What

makes you think that there may be indictments of high-level Obama administration

officials down the road?

It's clear that the Justice Department has been

carrying out extensive interviews with current and former senior administration

officials about David Sanger's excellent reporting on the Obama administration's

involvement in cyberattacks against Iran. At the same time, the administration

has established that it is willing to tolerate aggressive leak prosecutions

against current and former government officials. Equally, the White House is

allowing Justice prosecutors to make such decisions without political interference

-- as is proper (See: Richard Nixon). So if you add all that up, indictments

are a possibility.

Have

you talked to David Sanger, or to anyone else at the New

York Times, about the leaks to him? If so,

what did they say?

I have not formally approached the Times or Sanger about this investigation

-- the subject of my New Yorker

reporting was the separate prosecution of former C.I.A. officer John Kiriakou,

who pleaded guilty and became the first C.I.A. officer ever sent to prison for

providing information to the American press. In that longer story, I mentioned

the ongoing Sanger case as context, based on what I picked up along the

reporting trail, and I cited some reporting by the Washington Post, which appeared earlier this year.

Do

you think that the situation with Sanger and high-level Obama administration

officials may have altered the Times's coverage of national security issues? If so, how?

I don't have any reason to think that. The Times, under executive editor Bill

Keller and now Jill Abramson, has had to handle a succession of tricky

editorial and publishing decisions involving classified information, from

Wikileaks to these multiple leak investigations by the National Security

Division at Justice. There was the Kiriakou case, which involved the Times; a separate case involving former

C.I.A. officer Jeffrey Sterling and Times reporter James Risen; and now the

Sanger case. In the Risen and Sanger cases, the Justice investigations have

involved reporting done for books, in addition to reporting done for the Times. My reading from far outside is

that the Times editors have done very

well handling these dilemmas. It's a complicated responsibility, as I can

testify from experience at the Washington

Post. I'm sure there are at least a few calls the editors would like to

have back, but overall I think they've made courageous, responsible decisions

in the public interest.

Who

do you think might be indicted?

I don't know.

Do

you think such indictments would be justified?

Almost certainly not, particularly if they

involve heavy charges under the Espionage Act or other similar statutes, as

Justice has done in previous cases. As my story about the Kiriakou case

outlined, leak prosecutions are highly selective and they fail to take into

account the institutionalized failures and hypocrisy of the government's

management of classified information. David Pozen, a law professor at Columbia

University, estimates in a forthcoming Harvard

Law Review article that fewer than three in a thousand leak violations are

actually prosecuted, and the true percentage, if all leaks of classified

information could be counted reliably, is almost certainly much closer to zero.

These kinds of prosecutions -- aimed, apparently at creating a deterrent effect

-- in an atmosphere of such laxity just can't be justified as public policy,

even if they are permissible as a matter of law.

What does

all this say to you about how Washington (both in politics and journalism) works

these days?

The

Kiriakou case teases some of that out -- it's a very polluted environment.

There's a lot of opportunism from all sides. That's why they call Washington a

swamp. But I think the single biggest factor -- and a factor that could be

fixed -- is the broken system that over-classifies government information by

orders of magnitude. Until the government can credibly distinguish a real

secret from a phony or artificial one, prosecutions of leakers will always seem

selective and without adequate foundation.

Maj. Gen. H.R. McMaster on the future of ground warfare: First, we need to unlearn some bad lessons from the last decade

By April

Labaro

Best

Defense guest columnist

(March 20, 2013)

What's new in warfare? Not much, according to Major General H.R. McMaster, commanding general of the

U.S. Army Maneuver Center of Excellence.

Rather, McMaster said in a talk the other day (March 20) at the Center for Strategic and

International Studies, we've actually had to re-learn some basic concepts. The

most important one being that despite technological advances, there are

continuities in modern warfare that shouldn't be overlooked. This is where he

got all Clausewitzian on us, arguing that the continuities are that war is an

extension of politics, has a human dimension, is always uncertain and,

ultimately, is a contest of wills. Ensuring that these lessons don't have to be

re-learned in the future may be more important than the outcomes of the wars

themselves, he said.

There are also a few lessons that we shouldn't have learned, the

first "wrong lesson" being that the raiding approach leads to a fast, easy and

cheap win. It didn't work in Iraq or Afghanistan and is not likely to work in

the future, he asserted.

The second bad lesson is that wars can be outsourced to proxy

forces. What can be accomplished via proxy forces is often exaggerated, he

warned, in part because collaboration does not necessarily mean congruent

interests.

And what projections can be made about the future of ground

maneuver warfare? There's a lot of uncertainty, but McMaster said he doesn't

buy the arguments made lately by schools of thought that believe that the

future will be more secure and our ground forces will not face many strategic

surprises. Institutionalizing the lessons learned (and unlearning the "wrong"

ones) is a critical first step towards making more accurate projections and

improving the effectiveness of our ground forces,

especially in the face of fiscal austerity and the growing range of

unconventional threats.

Bots on the ground: The FBI's reading list on military robots and other lethal drones

I don't know if this list is expertly done, but I do like

how it is organized. Here are their other reading guides.

More drone

fun here.

March 26, 2013

The FP transcript (Xth and last): What the last 9 segments tell us about the state of the American confrontation with Iran

[Here are Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, and IX.]

Ricks: We are

almost out of time. Speaking of mutually shared decisions, the U.S. government

is probably going to face one this year on Iran. How has everything we've been

talking about shaped how we are going to be thinking about Iran down the road?

First David, then Michèle.

Crist: Well I

think it's all interrelated -- issues in Afghanistan, issues in Iraq, all

affect how we look at Iran and how we are positioned to be able to do something

about Iran. I think it's all interrelated. Lessons I think have been

institutionalized at least within senior leaders on some of the problems we had

in Afghanistan and Iraq, especially second- and third-order effects. What are

the consequences of different actions we take? What are consequences of

conflict in general? Is regime change a viable option? Isn't it a viable

option? If not, then how do we...? I mean, all that is in the background of

all the discussions. And I think it's been very healthy in many ways.

Ricks: One of the

issues that we've been talking about is the quality of civil-military relations

and straightforward, candid, honest advice from generals to civilian

leaders -- for which we have apparently just seen General

Mattis quietly fired. [Ricks note: I should have said "pushed out early."]

Crist: On the

record I won't comment on General Mattis's views.

I will say and I can say this with a certain honesty since

I've helped draft many of the memos: He has been very candid on what his views

of what needs to be done. I haven't seen anything like the Rumsfeldian approach

to stifling alternative views, and so as a consequence while...And some

people in the U.S. military -- maybe the political leadership isn't as

receptive as they would like on authority issues and some other response...the

dialogue is there, and frankly a lot of it gets to these ideas of what I have

always thought of as one of the intangibles where you have breakdown in

discourse between civilian and military leadership is as you say trust. And a

lot of it is personality based. Just personalities of the individual players

and how they personally get along, as well as concerns of political leadership.

Ricks: And you

have seen a trusting, candid exchange?

Crist: I have

from my level, absolutely. And I've sat in many -- not as many as Michèle and

some of the others here -- but a number of meetings with senior leaders on both

sides of it. And I have seen it be quite candid.

Ricks: My

impression is that the Obama administration has been almost afraid of Centcom

under Mattis and Harward -- the mad-dog symptom with two incredibly aggressive

guys. But I see Michèle shaking her head. Michèle, jump in.

Flournoy: I would

say of all the issue areas that I was exposed to in the deputies committees

process, there was none where we took a more deliberate, strategic,

questioning, and very candid approach than Iran. And it really started back --

this goes a few years back now when it was started up when Gates was still

secretary of defense -- and I think the thought that was put into exactly what

words the president says to describe our objective in Iran: Is it "prevent"? Is

it "contain"? That was debated, the consequences downstream of choosing one

versus the other, multiple senior leader seminars, war games looking at

different options, going down the road of different scenarios, very close

partnership with the military in actually setting the theater so that we are now

communicating a degree of deterrence to back up the policy of sanctions and

negotiations.

So I actually think on Iran, probably more than on any other

issue that I've seen, it's been very strategic, very comprehensive. There's no

idea that you can't bring to the table. There's no idea that hasn't been

debated. And people may have very strong views and disagree. But this is not

one where -- this was one where there was a real constant coming back to what

are our interests? What are our objectives? How do we make sure we are applying

rigor and not just going down the road towards confrontation with no limits or

no boundaries or no sense of what we are trying to achieve?

Crist: I would

add one more point in having looked at U.S.

strategy for a long time on Iran. One thing that I found interesting that

has evolved over the last few years that I haven't seen earlier is looking even

beyond the nuclear issue. What is our long-term relationship with this country?

Are we long-term adversaries? If so, how is that going to play out across the

region? And how do we counteract that? And also, are there areas, I think,

which despite the engagement piece, seemed to have died off, there has been a

lot of thought given -- are there areas where there is mutual cooperation? And

what will that lead to long term? Can we have maybe not rapprochement but some

kind of détente with Iran?

Ricks: So can we

start to get Putin to be aggressive again and drive Iran into our hands?

Crist: Yeah, it's

tough because in my personal opinion we are for a host of reasons adversaries

in the region. We have two different strategic views of what we want out of it.

But the issue is bigger than just the nuclear issue. The

nuclear issue is a symptom, more than a cause, of our problems.

THE END... -- or is

it?

Coll: Possible that senior White House officials may be indicted for leaking

Steve Coll's article in the issue of the New Yorker out this week, about a CIA

officer jailed for leaking, is interesting especially for two asides:

-- Over the past 100 years, he writes, 10 government

officials have been prosecuted for leaking. Six of them have been during the

Obama administration.

-- Coll predicts that this may come back to haunt the

administration: "If prosecutors find that senior White House officials broke

the law while communicating with Sanger, President Obama may be unable to

prevent high-level indictments."

Defense crime blotter: U.K. defense official who served in Af’stan guilty of sex assault

A woman who had too much to

drink fell asleep on a train. Mark Scully, an official in the British Ministry

of Defence, pretended to help her to a taxi but instead dragged her into some

woods and assaulted her. He worked on reconstruction issues in southern

Afghanistan in 2009-10, the Daily Mail

reports.

March 25, 2013

The FP transcript (IX): Did we really do any counterinsurgency in the last 10 years?

[Here are Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII.]

Fastabend : I

want to challenge us at the table. I want to give an example of some of the

things we lapse into. Half of us have said that the problem of the past decade

has been counterinsurgency and that we've done it and now we are all wrapped up

about whether we are going to do it again or not. I'm not sure we've done it.

You could equally assert that what we have done is brokered

two civil wars. And what's really striking to me about the difference between

the two experiences of the last decade and El Salvador: In El Salvador, there

wasn't that -- there were many moments that I had in many nights in Iraq

wondering about, "I wonder if we are fighting for the right guys

here." I think in retrospect we were brokering a civil war, and that's how

we calmed it down, by giving the Sunnis a chance to get it to a stalemate.

I think that civil war is still ongoing. I don't think Iraq

was a success unless we have an incredibly low standard for success. I can't

believe after over 6,000 dead and over 50,000 wounded -- not counting what's

happened to the Iraqis -- we leave behind a government that can't stop

overflights of arms to Syria from Iran. That counts for success? Really?

Alford: Would it

be better to still have Saddam there?

Fastabend: That's

a ridiculous statement, if you don't mind me saying. Of course not. It would be

better to have enough presence and influence in that area to have justified

that sacrifice having made it. Or having had a better decision process about

whether we are going to make that sacrifice or not. We'd be a lot better off in

the coming months in our face-off with Iran if we had two, three brigades

around the five strategic air bases in Iraq. It would definitely influence

their decision-making.

Alford: So that

should influence our decision in two years in Afghanistan.

Fastabend: Yeah,

it should.

Ricks: So you

think the way that the Obama administration resolved Iraq has fundamentally

weakened our position vis-à-vis Iran?

Fastabend: [Response off the record.]

Flournoy: Can I

just say for the record, a little bit of a point of fact. I think there was serious

discussion of a willingness of having a residual force. What changed the whole

dynamic was when [Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-] Maliki made the judgment that

he could not bring the guarantee of immunity for U.S. forces through the COR

[Council of Representatives] without risking a confidence vote on his

government, and therefore he wasn't willing to do that. Then you're left with

do you leave forces there with no immunities? That was a nonstarter. That's

what ultimately drove us to zero. It wasn't necessarily a preferred option for

the reasons you are describing.

Glasser: So

thinking about this in the context of Afghanistan and the decisions that are

yet to come, I have questions.

One, has anything changed that has made us take a more

strategic approach or to ask the right questions now after so long of somehow

not getting to the right set of questions over the next two years? Because that

certainly -- this is a very reasoned discussion, but I think pulling back you

get a sense that there's just a rush to the exits and that that's what we are

doing. In part because the politics and the public opinion in the U.S. have

already gotten us out the door, does that have an increased risk from a

military point of view?

Second one: This issue that Shawn raised of what is our

post-Vietnam legacy? What is the version of that for post-Iraq and

post-Afghanistan legacy? There were obviously crucial decisions that were made

in the 1970s after Vietnam about what the U.S. military force was going to be,

how it was going to be reorganized. Have we learned the lessons from that? We

know we are going into a period of transition. Are the right things happening?

Are the right preparations happening? Is there a process to understand what

this moment of transition can mean over the long term?

Chandrasekaran:

Can I tack another question onto that? Which is, what do we see as an

acceptable end state in Afghanistan given the parameters that are on the table?

Fastabend: I like

Tom's light footprint, having a few bases there from which you go out and hunt

every night.

Mudd: Just the

ability to eliminate the target we

went into. [CROSS TALK, INAUDIBLE.] The only way Kabul makes a difference is it

affects our capability to protect ourselves. That's it.

Ricks: David

Kilcullen, who couldn't be here today, maintained you can't do that because you

need the larger presence to acquire the intelligence that gives you the

targets.

Mudd: I don't

think that's true . . .

Dubik: Well, you

need the intelligence; whether it needs the larger U.S. presence to get that

intelligence is a separate issue. You can get the intelligence from Afghans...

[CROSS TALK]

Mudd: We can get

it in Pakistan.

Dubik: If the

relationship is correct and there is enough stability and trust that the

Afghans will give it to you. So I think that there's, for me anyway, a very

difficult set of questions to ask yourself.

First, what's necessary to protect our interests? Apropos of

why we went in there to begin with.

Second, what do I have to do in the country to be in the

position to make attacking al Qaeda a real capability? For me anyway, when I

ask myself that question, that gets to some degree of stability in the country,

some degree of relationship with the military and the population, and some

propping up of the military in terms of enablers to allow them to do what they

can do and, I think, want to do.

Crist: To me a

larger issue of defining success in Afghanistan is something that doesn't

destabilize Pakistan. I'm far more worried about the impact of a drawdown from

Afghanistan is going to have on Pakistan than I am . . . [inaudible].

Flournoy: I

wanted to respond to, "Is this all just a rush to the exits?" I think

you'd see a very different set of decisions if it were just a rush to the

exits. I think Dale actually described it well when he said that we are at a

critical juncture in the whole campaign, which is when you really do put the

Afghan forces you've built -- helped to build -- in front. And you still have a

hand on the back seat, but you want to do that before you draw down

substantially. You want to put them up front while you are there to be able to

help and advise and adjust. It's that milestone that's being -- the judgment is

that they are ready for the most part.

Let's have a year, year-plus, to make sure that this is

going to work and make adjustments as necessary and then get to the much more

circumscribed mission, which is about securing our counterterrorism objectives

long term vis-à-vis al Qaeda in the region and making sure that the Afghan

forces can at minimum prevent the overthrow of the central government and a

return to some kind of safe-haven situation. That's the critical thing -- that

does not take a huge long-term U.S. force. It requires some, and I would agree

with your point on at least in the near time some of those neighbors ought to

be pretty [INAUDIBLE OVER COUGHING]. So it can't just be advisors. If it were

really like wanting to wash our hands of this, you would see a very different

profile than what just came out of the White House and the meeting with Karzai.

Chandrasekaran:

It's hard to reconcile the kind of wash-your-hands view with what has been

telegraphed -- you know, deputy national security advisor talking about a

potential zero option even though that was likely just a negotiating tactic --

the very real possibility that it could be a presence anywhere between 2,500

and maybe 6,000. That's certainly sufficient to continue the necessary CT

[counterterrorism] missions.

But we've built an army there that is going to require an

enormous follow-on assistance presence as well as financial support, a part of

this that really hasn't gotten, I think, nearly enough attention. If the bill

for the sustainment of the Afghan security forces is somewhere around $4

billion in 2015 and if we only have 3,000 forces there, we can say all we want

to about trying to diverge the troop footprint from the congressional

appropriation, but our history shows us that those two things are inextricably

linked and that the fewer troops you have there the less chances you have of

getting the necessary money to support them. And we all know why the

communist-backed regime fell was when Moscow stopped funding Kabul. And so I

think we are not paying nearly enough attention to the money question.

But we still, I think, are not asking ourselves -- our

government is not asking -- whether this grand plan of building such a large

ANSF [Afghan National Security Forces] with such complex logistical

requirements, with such complex need for enablers, which will likely have to be

internationally provided for some years, is at all feasible there, and in the

time remaining between now and the end of 2014 should the security force

assistance mission be more than just pushing the Afghans into the lead but also

one last-ditch attempt to triage this to get to a smaller, more manageable

force that has a better chance of holding its own.

Ricks: This

actually goes back to the whole issue of, "OK, it might have been a better

original decision to go with local forces. Then, what sort of local

forces?" I actually think in Vietnam our fundamental error was in '62, '63

not emphasizing local forces and keeping our eye on that ball and just

"no, we are not putting our national forces in." It might not even

need to look like your forces. It might be better to have an indigenous force

that looks like an indigenous force. But Jim Dubik is an expert on this having

done this. Jim?

Dubik: I think

there's still some learning to be done on both our part and the Afghan part on

exactly what the ANA [Afghan National Army] is. And I'll just focus on ANA and

not the greater. We certainly, I think anyway, made exactly the right decision

in 2009 to expand the Afghan army and at the same time to disintegrate the

development effort, to take the combat forces and to accelerate them as fast as

we could and to allow the enablers to grow at what is going to be a really slow

pace. I think that was the right decision, and I think it got us to a better

point than we are now. The enablers, though for me, is really going to be a

very -- it's not a settled question, let's put it that way. For me, anyway, in

the near term, the set of enablers they need are pretty well known and have to

be externally provided.

But we've never really asked the Afghans in a way that is

meaningful. To say, "OK, how do you really want your army to be

organized?" We have asked them, so I don't mean to say we haven't. But

we've asked them in our presence, and that's like asking your younger brother,

"You want to go to a movie with me?" or "Oh, yeah, I'm going

with you." When you're not there, the answers might be different. The set

of enablers that we assume now -- and I've written about them and drank some of

that Kool-Aid myself -- but the enablers that we ask now may not be, after the

question is settled in, say, 2015, which I think is probably the right time

frame, the enablers that they really need or want. And the current organization

of regional commands probably will stay, but in our absence the arrangement and

relationship of those regional forces and how they're -- that I still think

there's some learning to occur in 2013 and 2014 when our presence is

diminishing and their sovereignty and judgment increases.

We saw a good bit of that in Iraq in 2009, '10, '11 when they

started making more independent decisions about their own force. Now I know the

two cases are significantly different, but there are certain commonalities.

Chandrasekaran:

On paper what was done starting in 2009, I think, made sense. There was a lot to

be said for it. But it just didn't fundamentally take into account the

political realities that we face here. It made assumptions about the

willingness of the U.S. government to continue sustainment, and it assumed that

there would be a robust U.S. security force mission. I don't think 2014 was on

the table in '09, but it made assumptions about robust U.S. support -- physical

support -- for many years.

Dubik: No

argument. But those assumptions, as questionable as those were, were better

than the assumptions of 2001 through '9, when we were going to grow the army at

such a slow rate that we would be there for 150 years before we were done with

it. Because we were growing it at the rate of its slowest -- we integrated the

force, so we weren't going to put a force out until all elements were ready.

Ricks: I remember

reading somewhere that we couldn't start training the Afghan soldiers until

they were literate. 99 percent of soldiers in world history have been

illiterate. Why can't we have a few illiterate soldiers here?

Blake Hounshell: Are

the Taliban literate?

Alford: Don't you

think they'll evolve back after we leave in '14? There'll be an evolution back

to their history and natural tendency?

Dubik: There'll

be a shift. I don't know if it's evolution back or forward. And that's what I

mean by learning. We are going to learn what actually works and what's actually

sustainable.

Glasser: I'm

raising that point actually only to get us to this question of clearly there is

a broad consensus around this table that the civilian-military dysfunction was

a key part of what got us to where we are. All I was trying to do was to

suggest how can we isolate what are sets of decisions or strategic choices that

do fall more on the military side of the ledger.

For example, Shawn started us off with his question about

rotation. Why wasn't there ever a decision? I don't know and I may be wrong

with this, but my guess is that is not so much coming from the civilian leadership

as this is how our Army works, this is how our system works. So, yeah, we have

to have a new commander in Afghanistan every year.

Dubik: I have a

different opinion. It certainly is a major component of the military decision.

But if you make the assumption that the war is going to last X amount of time

and [so] you don't need to grow the size of the ground forces, then you're kind

of left with a de facto rotation

decision. Or you're not going to allow policy-wise to go there and stay because

that's not an acceptable policy.

The nexus of those kinds of decisions is by its nature

civil-military. And in fact in my other comment about autonomy, that's why we

have the wrong model. These are shared

decisions, and they have to be shared decisions. The commitment of resources in

a military campaign is not merely a military decision. This is, and necessarily

will be, an important civilian component of the decision. The rotation stuff --

in Iraq for example -- if we are going to leave by 2004, then you don't have to

grow the size of the army, and, well, we're not really 2004. Maybe it'll be

2006: "OK, we'll just rotate our way through this."

(One last installment to come, about Iran, of course.)

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers