Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 120

March 20, 2013

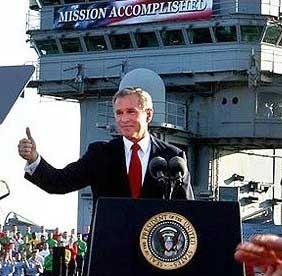

Weird quote of the day: Bush speechwriter says the Iraq war kind of just happened

David Frum, a former speechwriter

for President George Bush the latter, writes:

"For

a long time, war with Iraq was discussed inside the Bush administration as

something that would be decided at some point in the future; then, somewhere

along the way, war with Iraq was discussed as something that had already been

decided long ago in the past."

March 19, 2013

Two former Marine officers: Hey generals, stop whining about budget cuts and start to improvise, adapt, and overcome!

By Michael Haft and Harrison Suarez

Best Defense guest columnists

The inspector general's sign said to contact him in case of

fraud, waste, or abuse. We laughed cynically about which issue he might find

most egregious.

Would it be the non-alcoholic beer shipped around the world

into Afghanistan? The civilian contractors who slept all day in their hootches

and ignored the war going on around them? The ostentatious Post Exchange at the

Marine Corps's headquarters in Helmand Province, with its aisles lined by

televisions, air conditioners, and stereos?

Or maybe it would be the money-losing commissaries back in the

United States, a system of grocery stores receiving $1.5 billion in federal

subsidies every year? Or perhaps the Semper Fit girls in Camp Lejeune, who

acted like personal trainers but seemed like little more than beneficiaries of

a welfare program for Marine dependents?

Our brainstorming went on, but we never did find out. At the

time it wasn't our place. We had to pick our battles, and we weren't military

planners, we weren't financial management officers, we weren't whatever

military occupational specialty handles budgeting. We were just two infantry

officers looking around every day at all the bloat and wondering how it had

come to this.

If we've seen such excess in the Marine Corps -- traditionally

the most frugal service and one that receives just 4 percent of the defense

budget -- we can only imagine the extent to which it takes place in the other

branches. And as sequestration slowly comes into effect, it's worth asking:

Might a budget cut actually be a good thing for our military?

It could be, if our generals can make smart fiscal choices. And

although our top military leaders have spent months decrying the potential

effects of sequestration, it's worth noting that the Department of Defense budget

has just about doubled in the years since 9/11, that this figure doesn't

include money spent conducting the wars, and that what our leaders are

bemoaning is just a 7 percent cutback on the baseline budget.

As former Marines and members of the service that has always

prided itself on doing more with less, the discussion thus far has been

frustrating to watch. Very few people seem willing to question whether America

has gotten its money's worth from the ever-expanding military-industrial

complex.

Meanwhile, we aren't convinced. It's just too easy to call to

mind examples of questionable spending or hours of productivity lost due to

outdated systems. Meals at the dining facilities in Afghanistan cost more than

$25 per plate. Back in America, many of our computers still had floppy drives.

And all of these examples don't even get at the murky process of weapons

procurement and acquisition, in which no-bid contracts have become all too

common.

No question, when we were deployed we enjoyed those meals

tremendously on the rare occasions we visited large bases, and we were the

beneficiaries of new gear and weapons that came from some of those contracts.

But it is simply unbelievable that there isn't money to cut, that every dollar

spent goes to a worthwhile program.

Leaving Camp Lejeune for the last time a few months ago, we

drove by a series of newly-constructed LED billboards. On the screens, a

digital version of the American Flag waved in an imaginary wind. It felt

obscene, and as we passed each caricature, we couldn't help reflecting on all

the times our junior Marines had been forced to scrounge for necessary supplies

or to pay for better gear out of their own pockets.

Why was it that we had money for such frivolities, but

sometimes not the slings for our rifles? Why was it that every contractor we talked

to bragged about his six-figure income? Why was it that the new two-story chow

hall had a Mongolian barbecue, but there were never enough spots to attend

humvee training?

How did it come to this?

Our military leaders can do better. We believe that the budget

cuts will instill some much-needed fiscal discipline. We believe it's possible

to cut back without hollowing out the force. And we believe that it's time for

our generals to prioritize, something that has fallen by the wayside in this

era of military-industrial excess.

In the end, all we are asking is that our senior leaders take

some of the advice we were given as young lieutenants: Stop pointing fingers elsewhere. Figure it out. Improvise, adapt, and

overcome.

Michael Haft and Harrison Suarez are

former infantry officers in the United States Marine Corps. They served

together in Helmand Province, Afghanistan during the summer of 2011, where they

embedded with the Afghan Uniformed Police and the Afghan National Army. The

views presented here are their own and do not reflect those of the Department

of Defense or the United States Marine Corps.

The FP transcript (VI): What will Afghanistan look like in the long run?

[Here are Parts I, II, III, IV, and V]

Glasser:

Afghanistan is a very interesting question. Aside from the very early days of

pushing the Taliban out, which obviously was a military operation, or the

battle of Tora Bora or Shah-i-Kot,

since then there have been military operations certainly, but how would we

characterize in terms of as a war and then also what do we think of how the

U.S. military presence there will be remembered as? Is it going be "we

lost this war," or is it that it was a violent political conflict that

lasted for more than a decade and was unresolved?

Ricks: I'd like

to start by asking the historian and the Marine.

Crist: I agree

with General Dubik. We backed into this. That is the fundamental problem, is

the long-term strategy for a host of different reasons. I think we'll be

remembered as in some cases of duplicating a lot of the problems we've made in

our earlier wars, and then when we were faced with a crisis our natural

inclination, particularly in the U.S. military, is to fall back on doctrine. We

have a counterinsurgency doctrine -- if it worked in Iraq then it's going to

work in Afghanistan. And so you just sort of take that and transplant it as if

it's sort of a manual on how you're going to do that. And the problem with all

these wars is that they are all dependent on the dynamics, and they're

completely different. And so our response is a huge surge. Maybe it was the

right or wrong answer. I tend to think that it really ultimately didn't solve

much in Afghanistan, nothing like it did in Iraq, because the conditions were

different.

Alford: First

off, I think that we can look back in the future and say we succeeded. Not win

but. . . . . Because I do believe that we've spent enough time there, and the

transition we are getting ready to make is viable, I believe, from a partnered

operational design to an advisory piece and really get out of the way and let

them do it. I believe that their army -- in particular their army -- will be

able to keep it stable enough for this new government to muddle its way through

over the next few years. I think this third election -- a lot of people say the

second election in a new democracy is the most important -- it's the third

election here. And if it goes and people look at it as somewhat legitimate,

then they have a real chance, because the Taliban are not going to come

together as an army and take Kabul.

Ricks: Rajiv?

Chandrasekaran: I

think this in my view is going to likely wind up as some form of barely

satisfactory arrangement of sort of mildly unsatisfactory stalemate that will

not be seen as having been anywhere near worth the cost in dollars, and in

lives, and in limbs.

Look, I spent a lot of time in places where we surged troops

over the last several years. There is discrete impact. I've seen districts

where security has improved. It's incontrovertible. When you send in additional

numbers of U.S. troops, good things generally follow -- but for a discrete

period of time. We didn't achieve the sort of aggregate impact that we saw in

Iraq. And we all know the reasons why. Ultimately, I step back and say it was

not a wise expenditure of resources.

Stepping back even further, we fundamentally failed to grasp

the politics of that country [Afghanistan]. Our solutions were simply not

tailored to the environment. And ultimately I think in many parts of the

country -- it's already happening -- things will essentially revert back to

their natural order. And a natural order that may well in many parts of the

country be simply good enough for us. But could we have gotten to that natural

order without having spent as many hundreds of billions of dollars and as many

years as it has taken us to get there?

Alford: If we had

had the courage to make the shift four or five years ago? Absolutely. We took

some of the most decentralized people in the entire world and imposed one of

the most centralized constitutions on them. It's ludicrous that President

Karzai appoints a district governor and a district police chief. I'm telling

you, the people where I come from -- Rome, Georgia -- would rise up if the

president appointed the county commissioner. It's crazy.

Chandrasekaran:

Look, look, people criticize the United States for going around the world and

imposing democracy, and I think to myself, well only if we shared with people

the sort of democracy that made our country great. The Afghan Constitution on

paper centralizes power like no other state -- I suppose like North Korea. I

mean, it's crazy.

(More to come-first, about Syria and Libya)

Marshall: One of my concerns in World War II was British doubts about my army

Gen. George C.

Marshall was usually very close-mouthed about the tensions he felt with our

British allies during World War II. But in a 1947 letter to McGeorge Bundy, who

was helping write the memoirs of former Secretary of War Henry Stimson,

Marshall was pretty candid:

... there was quite

evident to me the feeling that of the British leaders that our ground army was

not going to be effective, at least in time to play a decisive part in the

fighting. As you know, Mr. Churchill had grave doubts about the comparative

fighting ability of the American divisions as compared to the German divisions,

though we should never say this publicly.... There was also the feeling that we

would have no commanders comparable to the British Field Marshal..."

(P. 236, The

Papers of George Catlett Marshall, Vol. 6: ‘The Whole World Hangs in the

Balance.'

Edited by Larry Bland, Mark Stoler, Sharon Stevens and Daniel Holt. Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2013. Buy it now! )

March 18, 2013

The FP transcript (V): Why weren’t we more savvy about our political objectives?

[Here are Parts I,

II,

III, and IV.]

Ricks: Rajiv,

you have been unnaturally patient. [Gestures dramatically with open right hand]

This is a man who, in Baghdad,

was famous for shouting at people, "Right now, right now, right now!" He was a great bureau chief.

Chandrasekaran:

I'm just taking all

this in. It's fascinating. I find myself agreeing with an awful lot of

what's being said around the table.

Just sort of building on a lot of this, I feel like the

military does a great job of looking at troop-to-task calculations. We don't we

do that on the diplomatic side of things? There was this assumption building

on, all right, September 12: Was the Taliban really our enemy? We then --

fast-forward a couple months -- think that we can have a reasonably strong

central government, civilian government, in a country with zero institutions,

with no human capacity. There just, from the very beginning, weren't the necessary

questions asked about what this would take, not from a military point of view,

but from a whole-of-government point of view.

All these assumptions get baked in that wind up being

completely contradictory and counterproductive to any efforts to build a stable

government, and at no point do we step up and say, "Wait. This doesn't

make sense." Part of it's a bandwidth issue. Part of it is, I think,

civilian sides of our government aren't doing the necessary sorts of

calculations about: Is this in our best interests? Is this doable? What would

it take to do it? And then, even further, getting right back to the beginning,

the question of space; one associated issue with this -- and I don't mean to

blame the victim here -- we don't do a good enough job of saying no to the

partners we're trying to help. Not just internationally, but the Afghans

themselves. You know, when the Afghans say, "We want to centralize power

in Kabul because, you know, Ashraf

Ghani says it's going to help fight corruption," we don't push back

meaningfully and say, "Yes, but it's completely unrealistic given the

capacity of your government." When [Afghan President Hamid] Karzai says,

"We want you ISAF forces to go

push into these districts because we've got bad guys there," we don't do a

good enough job of saying, "Wait a second; it doesn't make sense to do

that."

Ricks: General

Jabouri, listening to this, as someone who has dealt with the Americans, what

do you think of Rajiv's analysis? Are the Americans able to say no? Do they

make intelligent decisions, from your perspective as an Iraqi general and a

mayor of a city?

Jabouri: I think

the Americans, in the beginning, always take the ally from who said, "OK,

do everything they want." And they're strong. Like Chalabi,

Mowaffak al-Rubaie,

someone, they always say to them, "OK, I'm from this hand to this hand

[extends hands, palms up]." But after that discover they chose the wrong man.

The ally is not the man who says it is always OK to do things.

Ricks: So again,

a lack of sufficient thought, of understanding, going into the situation.

Jabouri: I think

also they depended totally on the people outside Iraq, not from inside Iraq.

The do not make a balance between that, but now we see the result in Iraq, with

what happened.

Ricks: Ms.

Flournoy?

Flournoy: I think

this point about really being thoughtful about your political objectives and

what's the goals and the strategy to achieve them and not being all things to

all people is really important. And I think it is something that we really

struggle with. When you ask why, I do think it does also speak to the imbalance

in our own investment as a government. I mean, we have this tremendously --

well, at least historically -- well-resourced military, well trained, well

cultivated. Obviously when you put thousands of Americans in harm's way, a lot

of attention is going to rightfully be focused in that direction to make sure

we know what we're doing and are managing that well.

But again, if you think what drives the success or failure

of these operations, it is your political objectives and your political

strategy and how well you frame those question. I would argue we don't grow on

the civilian side grand strategists, we don't grow political strategists. You

occasionally find them, and I can list a few I admire and respect. But I

remember one of the most difficult moments of the Iraqi government formation,

sitting in the embassy in Baghdad saying, "Well, what're we going to do?

What's our strategy to help them cohere?" Not that the U.S. was going to

dictate the outcome, but how are we going to help get over this hump and move

forward? Having the senior political officer at the time tell me, "Well,

that's not my job. My job, as the political officer, is to observe and

report." And I said, "I'm sorry. We invaded a country. We are

occupying this country. Your job is

thinking about the political strategy that's going to help put it back together

again on sustainable terms." But that's not what we train people to do;

it's not what we resource them to do. And I do think it's connected to this

fundamental imbalance of resources and that we didn't put enough time,

attention, thought, focus, resources into the whole civilian side of what we were

doing.

Dubik: In

conflicts that are essentially not winnable, militarily. The military

operations are necessary, but they're not sufficient. They're not even

decisive.

Ricks: Emile

Simpson makes this very good point in his new book, War From the Ground Up, as a young British officer who fought

in Afghanistan that you've got to turn Clausewitz on his head and look

as this as violent

politics, not as warfare that leads to a political outcome. A lot of it is

political operations coming out of the barrel of a gun.

Green-on-blue incidents are what happens when the conventional Army tries to operate unconventionally in Afghanistan

By "An SF Vet"

Best Defense guest contributor

When

SF moved there

they fell in on a ton of unvetted ALP that the regular Army had

"trained." Why was the regular Army standing up ALP, when they have

no real understanding about how to properly vet and conduct unconventional

warfare? Great question. Probably because a sorry officer made the poor

decision to allow this to happen.

So

the ODA fell in on hundreds of these poorly-trained, unvetted Afghans. So, they

did what they were told, set up a base out there, and began vetting these guys

with the last month they had in country. Fast forward to another sorry officer

that told the team to "Hurry up and vet these guys" so he could tell

higher how great of a job they were doing. When they said they had only vetted,

like, 40 percent, they were told that wasn't good enough, and the officer then

padded the stats because in his exact words, "I can't tell a general we

only vetted 40 percent."

I can't speak to everything that happened this past year, but this is the

sort of thing that causes green on blue. The conventional Army has no business

setting up ALP, but since that is the hot ticket these days, people only want

to mass-produce them. The current team on the ground has done a lot of

good things there, but it is hard (and dangerous) when you have leaders that

allow this to happen.

Morals of the story:

1) Start

giving higher the real story (I am talking to you, shitty, self-serving, careerist field grades).

2)

The war isn't over yet for the guys on the ground, so support them and

give them what they require to be successful.

3) Stop

allowing conventional Army to do unconventional tasks.

You want a 10th anniversary post for the invasion of Iraq? OK, here are the 10 biggest mistakes we committed in Iraq

By Col. Ted Spain, U.S. Army (Ret.)

Best Defense guest columnist

1.

Secretary Rumsfeld's deployment plans did not include an adequate number of

military police to control the routes during the ground war, nor sufficient

military police to help control the streets after the ground war. This

contributed to the Jessica Lynch fiasco and the chaos on the streets of

Baghdad.

2.

Law and order was not given sufficient attention in the pre-war planning. This

failed to provide a police system to provide security to the Iraqi citizenry

and to instill a sense of trust in the U.S. Army.

3.

The categories of the thousands of detainees were never clear, causing

confusion as to the proper legal treatment. Were they enemy, terrorist, or

criminal? What's the difference?

4.

The process of collecting intelligence from detainees was flawed from the

pre-war planning sessions, during the ground war, and during the subsequent

occupation. This set the stage for abuse, including the Abu Ghraib Prison

scandal.

5.

Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, the warden of Abu Ghraib Prison, was the

wrong leader at the wrong place at the wrong time. Her appointment resulted in

scandal and loss of trust in American forces by Iraqi citizenry.

6.

Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, commander of all military forces in Iraq

during the occupation, was in over his head and continued fighting the ground

war long after it was over.

7.

The Coalition Provisional Authority, under the leadership of L. Paul Bremer,

dismantled the Iraqi Army and the highest level of the Ba'ath Party. We lost

some of the most experienced personnel that were so vital in putting Iraq back

together again.

8.

Former New York City Police Commissioner Bernie Kerik was more focused on

padding his résumé and getting camera time than helping stand up a viable Iraqi

Police Services.

9.

Because standing up an Iraqi Police Service was focused on quantity, not

quality, we never completely knew who we could trust.

10.

President Bush's coalition of the willing was only a coalition in name. Even

those that were willing were not able. Only a couple of countries contributed

to gaining stability in Iraq.

Colonel Ted Spain commanded the U.S.

Army's 18th Military Police Brigade during the ground war and first year of the

occupation of Iraq. He was responsible for thousands of military police and

Iraqi Police across Baghdad and Southern Iraq. He is the co-author, along with

Terry Turchie, a former Deputy Assistant Director of the FBI, of

Breaking Iraq: The Ten Mistakes That Broke Iraq

,

which is being published this week.

March 15, 2013

Soldier poets of the Great War (VIIIth and last): A grim prophecy by Joseph Leftwich

This

is pretty impressive to have written not long after the beginning of World War I:

And if we win,

And crush the Huns

In twenty years

We must fight their

sons.

Tom Donnelly explains what that chart on Army force structure in WW II tells us

By

Thomas Donnelly

Best

Defense office of historical force structure analysis, French and Indian War to

World War II division

Beyond

the official story, that Army chart tells you a couple of

things:

1.

Army was never as big as planned.

2.

It got heavier -- more tanks and more artillery.

3.

It got heavier in different ways than planned -- fewer tanks, a lot more

artillery.

4.

Didn't buy as many aircraft as planned.

5.

Needed many more higher-echelon support troops than planned.

Questions

why:

1.

Were the differences a result of policy, manpower constraints, industrial

constraints, tactical learning?

2.

For a war that's supposed to be about the rise of tactical aviation and close

air support, the increase in artillery and failure to meet aircraft goals is

interesting.

3.

Higher-echelon support troops: Like other wars, this was fought in coalition

and at great strategic distances from the United States and at great

operational distances within the theaters. Is "tail" actually

"tooth?"

Rebecca’s War Dog of the Week: Why medics train with MWDs in combat theater

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

In this photo a flight medic with C Company, 2nd Battalion,

3rd Aviation Regiment, is being lifted into a MEDEVAC helicopter with Luca, a

military working dog with the 4th Stryker Brigade during training at FOB Spin

Boldak in Afghanistan. The medics participating in this February exercise were not military veterinarians or vet techs,

but were learning how to evacuate a MWD in the event that a handler was injured

or otherwise unable to care for the dog himself. In combat theater a dog is

treated as a full-fledged member of a unit and, if he were injured, would

receive the same kind of emergency life-saving care and attention as any other

solider, including the attention of a medic.

Still, treating an injured canine in the heat of battle

poses a unique set of challenges, especially if the dog is particularly protective

of its handler or is known to bite (note the muzzle in this photo). When a dog

team is out on a mission, the handler cannot be the only person in the unit who

knows what kind of medical attention his dog will need or how it should be

administered. All handlers are trained on how to treat their dogs, whether for

dehydration, broken limbs, or blood loss. But when working outside the wire, many

will carry cards detailing a kind of abbreviated "in case of emergency"

instructions so someone else (hopefully a medic) will know how to treat their

dogs if they are also wounded during missions.

As one Army

handler (who I interviewed for the War

Dogs book) told me last year, the first person a savvy handler will get to

know when assigned to a new unit is the medic. "Whatever you can do to help the medics out in your AO as a

handler, that's what you do. You introduce your dog to them. You let them play,

you know, get friendly with them." This handler wanted the medic, as well as the

rest of his team, to know his dog and to care about his well being because they

could be the ones in a position to save the dog's life.

RIP MWD Bak: This is a photo of Bak, a dog who was killed in

action on March 11 in Afghanistan. Few details about the circumstances of how

Bak was killed have been made public, but a memorial page is

active on Facebook, including an extensive photo gallery. His handler, Sgt.

Molina, is reportedly fine and, as of Wednesday, was awaiting transfer back to

the States.

Rebecca Frankel is away from her FP

desk, working on a book about dogs and war.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers