Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 123

March 6, 2013

More on why Jason Dempsey is wrong: Thoughts on our first poet of the Iraq War

By Peter Molin

Best Defense bureau of war poetry

Jason Dempsey's 13 February post on this site

decried the lack

of poetry by veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Nostalgic

for the kind of poetry written by great World War I poets such as Wilfred Owen

and Siegfried Sassoon, Dempsey writes that from verse, "we get a tactile feel for the war paired with

examinations of what it means for life writ large -- the purpose of art, as it

were."

I agree with Dempsey

that poetry helps us understand war (and all experience) best, but disagree

with his claim that our contemporary wars have been left uncharted by poets. Since

December of 2012 I have been reviewing art, film, and literature associated

with the war at my blog Time Now (www.acolytesofwar.com) in an effort to publicize authors and artists who

take the Iraq and Afghanistan wars as their subjects. I have already posted on

three poets -- Walter E. Piatt, Paul Wasserman, and Elyse Fenton -- who explore

how the contemporary wars have wrought alterations of perspective and emotion

on those who fight them and those who have been affected by them. Below I offer

a few comments on Brian Turner, by far the most well-known and important of

contemporary war poets.

The author of two

volumes of verse, Here Bullet (2005) and Phantom Noise (2010), Turner combines an MFA in creative writing

from the University of Oregon with seven years of service as an enlisted

infantryman, to include a tour in Iraq with the 2nd Infantry Division. His

poetry is at once subtle and sensational, accessible and complex. A good

example is the title poem of his first volume:

Here, Bullet

If a body is what you want,

then here is bone and gristle and flesh.

Here is the clavicle-snapped wish,

the aorta's opened valves, the leap

thought makes at the synaptic gap.

Here is the adrenaline rush you crave,

that inexorable flight, that insane puncture

into heat and blood. And I dare you to finish

what you've started. Because here, Bullet,

here is where I complete the word you bring

hissing through the air, here is where I moan

the barrel's cold esophagus, triggering

my tongue's explosives for the rifling I have

inside of me, each twist of the round

spun deeper, because here, Bullet,

here is where the world ends, every time.

Interesting about

the poem is the marriage of modern war imagery and emotion with the classical

verse form of the apostrophe (a direct address to a non-human thing), all

informed by a poetic smartness about half-rhymes, assonance, alliteration, and

other forms of sonic alertness. Thematically, the poem presents an original

take on bravery. The poem is half-taunt and half-cry of pain, the challenge to

the onrushing bullet a futile effort to both resist and understand war's

deadliness. The blur of emotions is matched by the interpenetration of the

imagery, where the rifle and bullet are given human qualities and the

soldier-speaker's body parts are weaponized, as in "the barrel's cold

esophagus" and "my tongue's explosives."

The metaphysical

musing of "Here, Bullet" is typical of many Turner's poems, which rarely stop

to consider events in which he personally participated. Occasionally though he

works in a biographical vein, too. A great example is "Night in Blue," from Here, Bullet. Many readers have told me

it is their favorite Turner poem:

Night in Blue

At seven thousand feet and looking back, running

lights

blacked out under the wings and America waiting,

a year of my life disappears at midnight,

the sky a deep viridian, the houselights below

small as match heads burned down to embers.

Has this year made me a better lover?

Will I understand something of hardship,

of loss, will a lover sense this

in my kiss or touch? What do I know

of redemption or sacrifice, what will I have

to say of the dead -- that it was worth it,

that any of it made sense?

I have no words to speak of war.

I never dug the graves of Talafar.

I never held the mother crying in Ramadi.

I never lifted my friend's body

when they carried him home.

I have only the shadows under the leaves

to take with me, the quiet of the desert,

the low fog of Balad, orange groves

with ice forming on the rinds of fruit.

I have a woman crying in my ear

late at night when the stars go dim,

moonlight and sand as a resonance

of the dust of bones, and nothing more.

When Turner isn't

considering his own emotions or the cosmological significance of war, his

dominant mode is empathy for those with whom and against whom he fights. Two

examples will suffice, one recording a birth in Iraq and one a death:

Helping Her Breath

Subtract each sound. Subtract it all.

Lower the contrailed decibels of fighter jets

below the threshold of human hearing.

Lower the skylining helicopters down

to the subconscious and let them hover

like spiders over a film of water.

Silence the rifle reports. The hissing

bullets wandering like strays

through the old neighborhoods.

Let the dogs rest their muzzles

as the voices on telephone lines

pause to listen, as bats hanging

from their roosts pause to listen,

as all of Baghdad listens.

Dip the rag in the pail of water

and let it soak full. It cools exhaustion

when pressed lightly to her forehead.

In the slow beads of water sliding

down the skin of her temples --

the hush we have been waiting for.

She is giving birth in the middle of war --

the soft dome of a skull begins to crown

into our candlelit mystery. And when

the infant rises through quickening muscle

in a guided shudder, slick in the gore

of birth, vast distances are joined,

the brain's landscape equal to the stars.

"Eulogy"

It happens on a Monday, at 11:20 A.M.,

as tower guards eat sandwiches

and seagulls drift by on the Tigris River.

Prisoners tilt their heads to the west

though burlap sacks and duct tape blind them.

The sound reverberates down concertina coils

the way piano wire thrums when given slack.

And it happens like this, on a blue day of sun,

when Private Miller pulls the trigger

to take brass and fire into his mouth:

the sound lifts the birds up off the water,

a mongoose pauses under the orange trees,

and nothing can stop it now, no matter what

blur of motion surrounds him, no matter what voices

crackle over the radio in static confusion,

because if only for this moment the earth is

stilled,

and Private Miller has found what low hush there is

down in the eucalyptus shade, there by the river.

PFC

B. Miller

(1980-March

22, 2004)

Turner poems record

such facts of modern war experience as IEDs, women in uniform, and PTSD, but

the characteristic most worth mentioning in conclusion is his deep interest in

history. Turner's not particularly interested in the war's political

dimensions, but unlike 99 percent of American soldiers, he is ever conscious

that the Iraq soil on which he fought had a long, richly-recorded existence

before America turned it into a 21st century battleground. This pre-history of

Operation Iraqi Freedom wells up in Turner's poetry in the form of references

to ancient texts, images of ghosts, evocations of ancestors, and readiness to

consider contemporary events in a temporal context extending deep into the past

and into the future.

To Sand

To sand go tracers and ball ammunition.

To sand the green smoke goes.

Each finned mortar, spinning in light.

Each star cluster, bursting above.

To sand go the skeletons of war, year by year.

To sand go reticles of the brain,

the minarets and steeple bells, brackish

sludge from the open sewers, trashfires,

the silent cowbirds resting

on the shoulders of a yak. To sand

each head of cabbage unravels its leaves

the way dreams burn in the oilfires of night.

Turner, the first or near-first Iraq veteran to

turn his war experience into verse, has established an impressive standard of

both poetic craft and thematic depth for the poets who have followed him. Still,

no one artist says it all, and other poets such as Piatt, Wasserman, and Fenton

have also found interesting and important ways to use their verse to document

how the war has been fought and how it has been felt. We wait to see what they

bring us in the future and what other poets join the conversation.

Peter Molin is a U.S.

Army infantry officer with deployment experience in Kosovo and Afghanistan. He

holds a Ph.D. in English literature from Indiana University. The opinions

expressed herein are his alone and do not reflect DA or DOD policy.

Red Bull’s deployment haiku contest

Meanwhile, Chief

Red Bull is holding a haiku contest. Here's a

sampling he sends along:

Eight deployments down

most surreal thing I've

seen is

KAF's TGIF

*****

This summer sandstorm

Couldn't blind the

first sergeant

To my day-old shave.

*****

A circling bird calls:

War on TV is phoned-in,

COIN-operated

*****

Where is the Kandak?

Alone at the command

post.

Oh, it's Thursday

night!

*****

Sprint in a flight suit

Long tarmac, rip my

crotch

Warm Iraq breezes

*****

Our trucks move like

ducks

waddling between ponds

and now

stuck in this wadi

*****

Silly pogue don't know

Gunslingers don't drink

lattes

Macchiato sir?

March 5, 2013

Vali of the Donilons

In the hot new issue of Foreign Policy, Vali Nasr,

now dean at Johns Hopkins SAIS, but formerly at the State Department, offers a

scathing portrayal of President Obama's national security team. The villain

of the piece appears as "the White House," which is referred to 63 times, most

of them negative. Readers of this blog will not be surprised by Nasr's

conclusion that "the president had a truly disturbing habit of funneling major

foreign-policy decisions through a small cabal of relatively inexperienced

White House advisors whose turf was strictly politics."

Every administration has turf fights, but this article makes

me thinks Obama's have been memorably bad. Other examples:

"At times it appeared the White House was more interested

in bringing Holbrooke down than getting the policy right."

The White House "jealously guarded all foreign

policymaking."

"Turf battles are a staple of every administration, but

the Obama White House has been particularly ravenous."

"Had it not been for Clinton's tenacity and the respect

she commanded, the State Department would have had no influence on policymaking

whatsoever. The White House had taken over most policy areas: Iran and the

Arab-Israeli issue were for all practical purposes managed from the White

House."

Some hard lessons that may help in Mali

By Gary Anderson

Best Defense office of hard lessons

Over the course of the past 20 years, I have observed or

participated in counterinsurgency campaigns in South Lebanon, Somalia, Iraq,

and Afghanistan in both military and civilian capacities. Some were done

poorly, some successfully. The one thing that I have learned is that each is

unique in its own way and there are no templates that will work in all cases.

Mali is a good example of uniqueness, and there are some lessons from each of

my experiences that pertain to that particular situation.

As a U.N. observer in Lebanon, I watched the Israelis go from

liberators to hated occupiers in a way that was completely unnecessary, and caused

them needless grief. Like the French in Mali, the Israelis chased off an

unwanted foreign presence -- in their case, the Palestinians were viewed occupiers

by the largely Shiite southern Lebanese population. Unfortunately, the Israelis

had a tendency to view any armed Muslim Arab as a threat. Consequently, Israel

opted to arm a minority Christian-led militia. This action inadvertently

created Hezbollah, which became a far greater threat to Israel than the

Palestinians ever could present. The Israelis would have likely been far better

off arming individual villages for self-protection without taking sides in the

ongoing Lebanese civil war and positioning themselves as an honest third-party

broker in the inevitable civil disputes in South Lebanon.

Mali is a civil war as much as an insurgency. The southern third,

and the government, are dominated by blacks while the northern part has a considerable

population of light-skinned Tauregs of Berber origin. Although heavily armed al

Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) foreign fighters have provided the Taureg

separatists their military advantage, in the recent past the Tauregs have shown

an inclination to negotiate, and will likely do so again if the jihadists can

be ejected. This is where the French need to avoid Israel's Lebanon mistake and

become facilitators of real negotiations.

In Somalia, we learned the lessons of cultural ignorance the hard

way. After a largely successful humanitarian intervention to stop mass

starvation, we and the United Nations ignored the traditional clan system of

the Somalis and made the mistake of trying to supplant it with alien Western

style democracy. Ironically, the attempt by the former Somali dictator to

ignore the influence of the clans was what began the disastrous civil war that

caused the collapse of Somalia to begin with. The Americans and United Nations

overreached in Somalia. The Malian government understands that it needs to

rebuild the democratic institutions that were toppled by the disastrous

military coup that initiated the current crisis. We could help in

reestablishing Malian governmental legitimacy.

In Iraq, we succeeded largely because we were able to separate the

foreign jihadist insurgents from the indigenous Sunni nationalist insurgents

through a soft power combination of diplomacy and money. The use of soft power

such as this in driving a wedge between the Tuareg people and AQIM will be critical

to any potential success.

In Afghanistan, we continue to learn perhaps the most difficult

lesson of all. To successfully help a host-nation government fight an insurgency

requires that the host-nation government wants to address the root causes of

the insurgency. The Afghan government never accepted that principle, and may

never will. That does not mean that governance cannot be improved in Mali. Good

governance is not necessarily expensive. I have come to the conclusion through

bitter experience that the more development money we throw at a country, the

worse the government gets, as money breeds corruption. In Mali, we would be

better advised to spend small amounts of money on rule of law training and

local management techniques for local officials, particularly Tauregs and other

local officials in the north. Insurgencies are like politics in that they are

basically local.

In rebuilding the Malian military, we need to remember that the

organizer of the coup debacle was American trained. As Western trainers try to

retool the Malian Army, we need to remember human rights training and the

importance of civilian control over the military as much as small unit

training, patrolling, and other tactical skills. In addition, the Department of

State and French Foreign Ministry need to stress civil-military relations in

training national level Malian officials.

I am one of those opposed to U.S. intervention in Syria. The

infestation of Islamic radicals in the ranks of the rebels is even greater than

it was in Afghanistan during the revolt against the Soviets. I favor a

negotiated settlement with the Baathists that will allow them a reasonably soft

landing as we brokered between the government junta and the rebels in El

Salvador two decades ago, but Mali is different.

If we use Special Operations Force troops to train local militias

and retool the Malian Army into a professional force capable of supporting a

democratic civilian government, we can do so cheaply and effectively; that is

the SOF mission. More importantly, they could help build village-level self-defense

militias in the north to prevent the now hated Islamists from returning. Again,

a relatively inexpensive operation.

Likewise, the State Department and USAID now have hard-earned Iraq

and Afghanistan experience in coaching good governance and anti-corruption at

the national, provincial, and local levels. This ought to be exploited before

it atrophies. Again, this can be done affordably. Mali is not hopeless, and it

can be a model for the right way to stabilize governments and fight Islamic

extremists.

Gary Anderson

is a retired Marine Corps colonel who was a governance advisor in Iraq and

Afghanistan. He is an adjunct professor at the George Washington University

Elliott School of International Affairs.

A Navy expert: 21st century leaders need to communicate by listening as well talking

From a recent talk at the Naval War College by Rear Adm.

John Kirby:

The

whole debate over strategic communications ignores the reality that we live

increasingly in a participatory culture. People aren't waiting to lap up our

messages anymore. They don't want access to information. They want access to

conversation. They want to be heard. Ours is a post-audience world where we can

no more control the narrative than we can control the weather.

What

we can do is find ways to take part in that conversation, to inform it, even to

guide it at times. But that requires a certain humility that I worry we don't

always possess. It requires us to listen as well as to speak, to solicit as

well as to inform, to be willing to admit of our own shortcomings and accept

sometimes brutally frank feedback.

...

The point is that I know my credibility -- and that of the Navy -- is enhanced

when I endeavor to join a discussion rather than to lead it. That can be a hard

thing for us to do, letting go of leadership a little. But in this brave, new

world of instant communications letting go actually means getting ahead.

March 4, 2013

Corruption and Afghanistan: Do we really understand what is going on and why?

I've been reading a book by an economic

historian that made me think of the anti-corruption campaign in Afghanistan in

a different way.

The book is Douglas Allen's The Institutional Revolution.

I picked it up because I was so taken by his discussion in an academic article

about the organization of command and control in

the Royal Navy during the age of fighting sail.

In this book, Allen, looking at the roots of

the industrial revolution, argues that the more a society is subject to the

whims of nature (drought, flood, wind, and such), the more likely it will

appear to modern man to be corrupt. The last sentence in the book is, "What on

the surface seem to be archaic, inefficient institutions created by people who

just did not know any better, turn out to be ingenious solutions to the

measurement problems of the day."

What we call "corruption" is basically the way

the world worked before 1860, and much of the world still does today. Indeed,

he argues that the British empire was built on a complex web of bribes,

kickbacks, and what economists call "hostage capital."

"Institutions are chosen and designed to

maximize the wealth of those involved, taking into account the subsequent

transaction costs," Allen writes. "The institutions that survive are the ones

that maximize net wealth over the long haul."

I think Allen focuses a bit too much on

standardization and measurement as driving forces in the changes in 19th century institutions, such as public policing. For example, my experience of

theft in small towns is that people often know who does it, and handle it

quietly and privately, while in big cities, they have no idea who the criminals

are. Hence the need for public police forces in 19th century England

as there was a massive movement of people from the countryside to the cities.

Allen also changed the way I understand

aristocracy. He argues, persuasively, that the role of aristocracy was to

provide loyal, competent, honest service to the crown. Thus their wealth had to

be in land that could be confiscated. An aristo who invested in industry was no

longer hostage to the crown, and so could no longer be trusted entirely. Hence

the creation of strong disincentives to pursuing other forms of wealth, one

reason that the ruling class in England tended to sit out the Industrial

Revolution.

Overall, a really interesting book, full of

thought-provoking facts and assertions.

General Eikenberry on the unforeseen consequences of the all-volunteer force

I've been critical in the past of

Amb./Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Karl Eikenberry, so it

is a pleasure to report that he has a thoughtful article, "Reassessing the All-Volunteer Force," in the Winter 2013 issue of the Washington Quarterly. He argues that oversight of the military by

both the Congress and the media has diminished. "Indeed, nearly abject

congressional deference to the military has become all too common."

I think he is right. I hope we will see

a re-assertion of congressional interest and prerogatives in the coming years.

The more I think about it, it seems to

me that the AVF has been a tactical success and a strategic failure, in that it

detached the American people from their wars. And so we do not wage them as

well as we should.

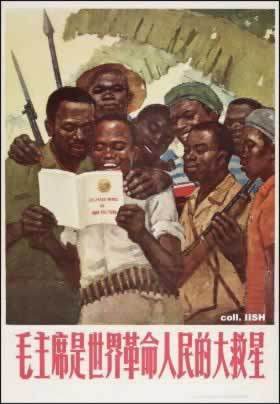

Out of China, into Africa: Tracking the ways of private Chinese investment

By

Katherine Kidder

Best

Defense office of Communist Chinese capitalist studies

China's

growing role in Africa over the past decade-or-so has raised some eyebrows. Questions surrounding

China's motives for investment abound: Are they purchasing U.N. votes? Simply extracting natural resources? Expanding the rhetoric of revolution, as it did in the 1960s?

Yet

most of these questions presuppose state-led investment in Africa. Xiaofang

Shen, a visiting scholar at the Johns Hopkins University SAIS China Studies

Program and former investment climate specialist at the World Bank, said in a

recent talk at SAIS that the more notable increase over the past decade

has been the rise in Chinese private-sector investment on the continent.

Pre-2001,

Chinese private investment in Africa was negligible; by the end of 2011, there

were 879 private companies and OFDI projects registered with the Chinese

Ministry of Commerce. Contrary to the image of state-led extraction, Chinese

entrepreneurs focus their energies mainly on manufacturing and service

industries. They increasingly are forging relationships with local management,

and aware of the value of learning local customs, religions, and languages.

So,

what does this mean for the West? Interestingly enough, Chinese private

investment in Africa may be a hat tip to Western models of development and

governance: Xiaofang Shen's study finds that going overseas to do business was much easier for up-and-coming Chinese

entrepreneurs than starting a business in inland China.

Most of China's industry grew up in the 1980s

and 1990s, with little-to-no regulation. By contrast, many African laws (at

least on paper) were copied and/or imposed by the West through such mechanisms

as Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). As a result, Chinese entrepreneurs

find African processes more conducive to business, from obtaining licenses and

navigating the bureaucratic process to trusting that the food they eat for

lunch is safe. African governments face higher incentives to improve

infrastructure and devote resources to political stability and regulatory

efficiency in order to attract capital -- precisely the same goals reflected in

SAPs.

March 1, 2013

My questions about the Vietnam War: I suspect there is a lot more to say about it

For a symposium put on recently by FPRI, I drew up a list of questions I have about the Vietnam

War. Here they are:

How

much new information about the war is coming out? Is there more to come? How is

it changing what we thought we knew? There has been a lot out of North Vietnam

over the last 20 years. So far, as one person at the symposium said, it is as

if our histories of the war were written by Custer.

Second,

to what extent do these new revelations challenge our basic assumptions about the war? For example, we often used

firepower lavishly in Vietnam. But what do enemy accounts and documents tell us

about our use of firepower? How much empty jungle did we kill? How many

civilians did we turn against us?

That

leads to a broader question. There is an assumption that for much of the war,

we were good tactically. Were

we?

When

Westmoreland said "counterinsurgency," what did he mean? He said he meant

"firepower." I see some historians these days waving memoranda they've found

saying Westy wanted COIN, and assume he didn't mean that. Such an approach

strikes me as a bit lacking in skepticism. Here's a surprise: Government

documents do not always reflect the truth, or even what the author really meant.

Officials sometimes have other purposes -- to set up a straw man, to record a

dissent, to show they are complying when they really are not, or perhaps to

cover someone's butt. Just as oral histories have problems, so do smoking gun

documents.

Generally,

can we learn more about what worked and what didn't? I think Mark Moyar is on to something. I

was struck, for example, that the Vietnamese army's official history of the war

concedes that the strategy of the imperialists

and the puppets worked very well in 1968 and 1969. Rice taxes

on the peasants were cut off, Viet Cong lived near starvation, and recruiting

went way down. Why were we unable to take

better advantage of those developments? So the other shoe for me is: How

bad were U.S. forces in that period? And how inept were some commanders in the

field that they could not push on that open door?

Related:

Were enemy forces just lying low in 1969 and 1970, waiting for the politics of

the thing to work out?

Finally,

some other, broader questions:

Wade

Markel wrote that in Vietnam, we developed "an Army that avoided error rather

than exploited opportunity." Is that correct? If so, how and when did it

happen?

Was

Vietnam a flawed strategy or poor operational execution? Or both?

Last

question: Is the military today telling itself a tale similar to the one it

told itself after the Vietnam War, that basically it did everything right but

the civilians screwed it up?

Soldier poets of the Great War (VI): Encountering corpses in no-man’s land

Arthur

Graeme West leads a small night patrol that encounters

...half a dozen men

All blown to bits, an

archipelago

Of corrupt fragments,

vexing to us three.

Even

more horribly, Edgell Rickword grows comfortable with a corpse lying out in

front of his position, and reads aloud to him -- until the body rot grows too

repulsive:

He stank so badly,

though we were great chums

I had to leave him;

then rats ate his thumbs.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers