Daniel A. Masters's Blog, page 12

January 4, 2025

The Best of Friends and Most Determined of Enemies: A Pennsylvania Surgeon Among the Confederates After Chancellorsville

Ordered across the Rappahannock after the conclusion of theBattle of Chancellorsville, Surgeon John W. Rawlins of the 88thPennsylvania might have expected a grim task ahead of him. What surprised thePennsylvanian was the courtesy and kindness with which he was treated by hisConfederate hosts.

Arriving atthe field hospital set up at Salem Church, Surgeon Rawlins recalled the warmfriendships that soon developed with his counterparts in gray. “During our stayof four days and four nights at this church and in its vicinity, we had a greatmany Rebel visitors from the generals down with whom we freely expressedopinions, discussing politics and the war freely,” he wrote. “We were treatedwith much courtesy and invariably with politeness. We had the pleasure ofmeeting surgeons from Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia,some of whom had been college mates of ours in Philadelphia, and others werewell acquainted with many of our former friends. Our social evenings at SalemChurch with the Rebel surgeons seemed more like the reunion of well-triedfriends after a long separation. We shook hands and parted the best of friendsbut the most determined of enemies.”

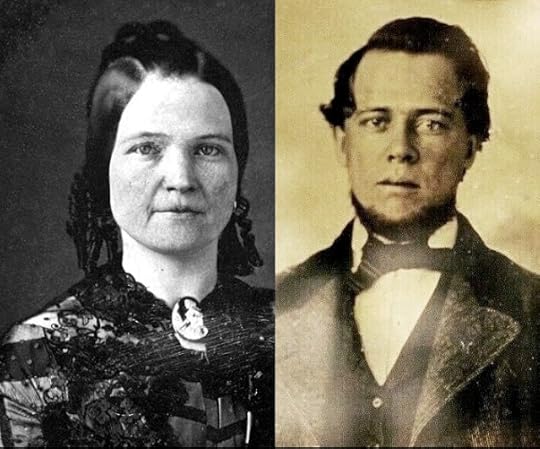

Among thesurgeons he met was Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, the younger brother of MaryTodd Lincoln. “I showed him a likeness (on a $10 greenback which by the way isa very true likeness) of his distinguished brother-in-law,” Rawlins noted. “Dr.Todd remarked that he considered the “circumstance no credit and no discredit.”Someone suggested that he should send Mrs. Lincoln a letter; he declined butsaid we “might give his respects.”

Surgeon Rawlins’remarkable letter first saw publication in the May 20, 1863, edition of the LancasterDaily Evening Express published in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

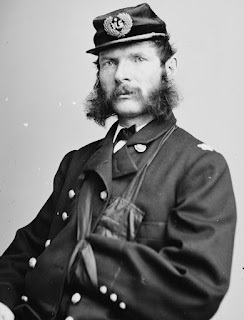

Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins of the 88th Pennsylvania was comfortably settling into camp when orders came for him along with a half dozen other surgeons to recross the Rappahannock and provide care for wounded Federal soldiers. Rawlins ended up at Salem Church, the scene of vicious fighting on May 3, 1863. Rawlins speaks little of the medical tasks he performed, focusing instead on the friendships that developed between the Federal and Confederate surgeons. "We shook hands and parted the best of friends and but the most determined of enemies," he noted.

Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins of the 88th Pennsylvania was comfortably settling into camp when orders came for him along with a half dozen other surgeons to recross the Rappahannock and provide care for wounded Federal soldiers. Rawlins ended up at Salem Church, the scene of vicious fighting on May 3, 1863. Rawlins speaks little of the medical tasks he performed, focusing instead on the friendships that developed between the Federal and Confederate surgeons. "We shook hands and parted the best of friends and but the most determined of enemies," he noted.

Camp in the pines, Virginia

May 14, 1863

During theafternoon of the May 6, 1863, we had another thunderstorm, accompanied by heavyrains, which made our camping place that night very muddy and unpleasant. Butfortunately, I succeeded in obtaining possession of an outhouse partly filledwith hat which I converted into a hospital for the night, furnished a drylodging place for some 10-15 guests.

The next day,May 7th, we encamped under shelter tents near our present locationand on the 8th, we pitched tents and prepared to make ourselves comfortable.But while I was sitting by a warm fire in my little camp stove between 5 and 6o’clock, drying my feet and congratulating myself upon the creature comfortswhich I was about to enjoy, I received an order to proceed immediately withinstruments and report to Dr. A. of the U.S. Army at Banks’ Ford. I would gowith a flag of truce within the enemy’s lines to attend our wounded on thebattlefield. In a few minutes, I was on the road and was joined at corpsheadquarters by six other surgeons. We proceeded on our lonely, devious, anddark road in pursuit of science or rather practice under difficulties.

After beingconducted from one line of pickets to another, we got lost, but after discoveringa farmhouse in the distance, we determined to go there and obtain a guide or remainthe balance of the night. Fortunately, we found Dr. A. there to whom we were toreport. We soon unburdened and fed our horses, unrolled our blankets on thefloor and went to sleep supperless. Next morning, after a good breakfastfurnished for us at 50 cents each by the kind farmer, we proceeded with ourboats and several wagonloads of supplies to Banks’ Ford, which, by courtesy ofthe Rebels whose pickets lined the south bank, allowed a number of us to cross.The balance was sent up to the United States Ford to cross over to thebattlefield of Chancellorsville. Three of us went on in advance, being guidedby a Rebel lieutenant colonel and a major on horseback who courteously carriedour field cases of instruments. We had to leave our horses on the north side ofthe river, not being able to get them over.

The first lotof wounded we came to numbered about 70 and occupied the barn of a man namedHogan. Our services being more urgently needed further on, we proceeded (afterstopping at several houses on the way where lots of 4-6 men were quartered) toSalem Church. This church is a brick building (of good size for a countrychurch) and is situated on the Plank Road leading from Fredericksburg toChancellorsville. Here we found nearly 100 of our wounded under the care of Dr.O. of the 121st New York who had been detained by the Rebels. [The121st New York under the command of Colonel Emory Upton reportedlylost 48 killed, 173 wounded, and 55 missing in the engagement near Salem Churchon May 3, 1863; 32 of the 55 missing were subsequently discovered to have beenkilled in action.]

During ourstay of four days and four nights at this church and in its vicinity, we had agreat many Rebel visitors from the generals down with whom we freely expressedopinions, discussing politics and the war freely. We were treated with muchcourtesy and invariably with politeness. We had the pleasure of meetingsurgeons from Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia, some ofwhom had been college mates of ours in Philadelphia [Jefferson Medical School], and others were wellacquainted with many of our former friends. Our social evenings at Salem Churchwith the Rebel surgeons seemed more like the reunion of well-tried friendsafter a long separation. Although our political sentiments were as wide asunderas the poles, I am sure both parties were highly gratified by the courteous,kind, and gentlemanly treatment received at each other’s hands. We shook handsand parted the best of friends but the most determined of enemies. I could notbut contrast their conversation and conduct with that of our Copperhead friendsof the North. The Rebel gentleman is a noble lion, the Copperhead a sneakinghyena.

On Sunday May10th, the Rebels having furnished is with an ambulance or two andseveral wagons, we placed in them about 50 of our best cases and we threesurgeons accompanied them on foot about four miles to Fredericksburg where theywere paroled and permitted to be sent across by General Barksdale. Having leftsufficient surgeons on the battleground, we proposed to cross over and rejoinour commands but General Barksdale would not permit us. I made a virtue ofnecessity and remarked to Barksdale that it was immaterial as we had so farbeen treated with great courtesy and anticipated nothing less than acontinuance of the same. He replied that there was a hotel in Fredericksburgwhere we might go, but knowing very well what poor fare and high charges wemight expect at a hotel in Rebeldom, I suggested that as we could still rendersome service at Salem Church, I would prefer to return there. He replied thathe had no objection to that.

So, we walkedback again accompanied a great part of the way by three Rebel soldiers whoentertained us with their account of the battle. We entered Fredericksburgabout an hour after their great General Stonewall Jackson died; he was woundedin both arms, only one of which he would suffer to be amputated. The Rebelssaid he was wounded accidentally by his own men who mistook him for a Unionofficer. They also state the cause of his death was pneumonia, but it is moreprobable, I think, that it was consequent upon his wounds and those woundsreceived from the enemy in battle as it was said he took command in person ofthe Stonewall Brigade after the death of Brigadier General Elisha Paxton. Inpassing through Fredericksburg, we witnessed the burial of a Rebel officer andthe brass band striking up a tune immediately behind us, we marched for thefirst time in our lives to Rebel music.

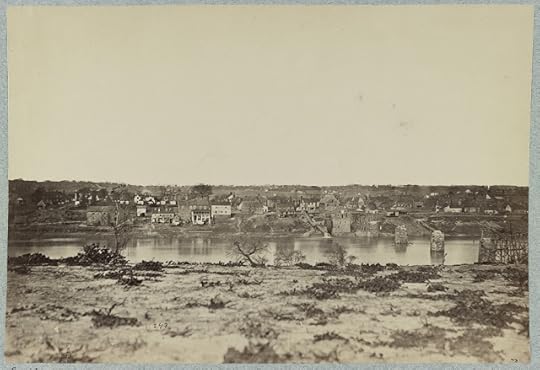

Fredericksburg, Virginia, in February 1863. By May, Surgeon Rawlins observed that "Fredericksburg is a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen. Many of the finest houses were deserted, the gardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers."

Fredericksburg, Virginia, in February 1863. By May, Surgeon Rawlins observed that "Fredericksburg is a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen. Many of the finest houses were deserted, the gardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers." Fredericksburgis a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen, but thosefew seemed quite interested in the appearance of “the Yankee officers.” A lotof well-dressed boys volunteered to show us the way down to the crossing whichwas opposite the Lacey House. Many of the finest houses were deserted, thegardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers. We passed the celebratedMarye’s Heights which Sedgwick had the honor of taking but could not keep; wewalked back the same road many of the troops took tom escape at Banks’ Ford.

But, more unfortunate than us,they met a lion in their path in the shape of General [Cadmus] Wilcox’sbrigade, strongly posted behind breastworks made of planks taken from the PlankRoad. The Rebels say this was constructed after the battle, but I do notbelieve a word of it for the walls, windows, and ceiling of the brick churchare thickly strewn with the shreds of garments, letters to Federal soldiers,memorandum books, etc. All show plainly that a desperate contest occurred thereand the numerous graves provide still better proof. The Rebels say our troopsadvanced without throwing out skirmishers; the Rebel skirmishers quietlyretiring and leading the Federals right into the open space in front of theRebel lines.

The officerswe met with were nearly all intelligent and good-looking gentlemen. Some ofthem wore uniforms of coarse material, but all appeared to enjoy good healthand to be able to endure considerable service. But they did not endeavor todeny the fact that their men were all in the field, but they also assume ourconscripts won’t fight and that their veterans are more than a match for ours,having full confidence in their commanders. They estimate our so-called peacemen and Copperheads (Vallandigham, Woods, Sanderson, etc.) at their proper value.They know these truckling doughfaces of old and spur their sympathies as theywould the caress of a troublesome, fawning spaniel.

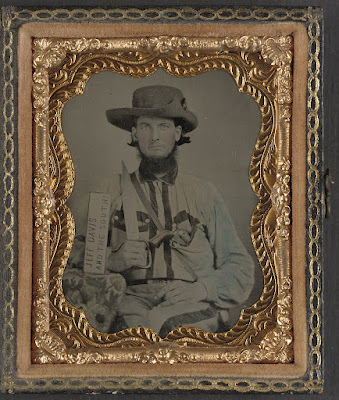

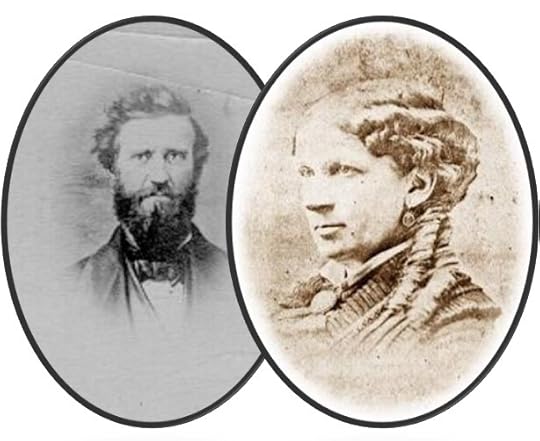

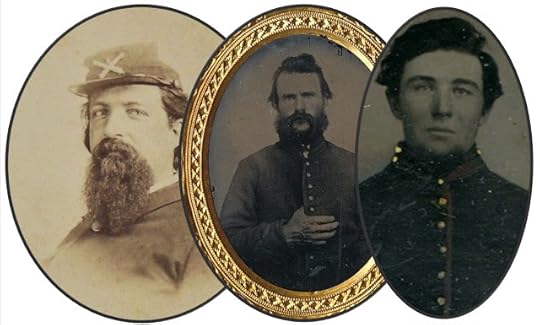

Mary Todd Lincoln and her younger brother Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, who at the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville was serving as the chief brigade surgeon for Brigadier General Paul Semmes' brigade of Georgians. When it was suggested that Dr. Todd send his older sister a letter, he declined but offered that the Federals "might give his respects" to Mrs. Lincoln.

Mary Todd Lincoln and her younger brother Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, who at the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville was serving as the chief brigade surgeon for Brigadier General Paul Semmes' brigade of Georgians. When it was suggested that Dr. Todd send his older sister a letter, he declined but offered that the Federals "might give his respects" to Mrs. Lincoln. Among ourvisitors was Dr. [George Rogers Clark] Todd, chief surgeon of Semmes’ brigade.Dr. Todd is a brother of Mrs. President Lincoln. I showed him a likeness (on a$10 greenback which by the way is a very true likeness) of his distinguishedbrother-in-law. The Rebel officers all took a good look at the engraving. Dr.Todd remarked that he considered the “circumstance no credit and no discredit.”Someone suggested that he should send Mrs. Lincoln a letter; he declined butsaid we “might give his respects.” The last time he saw Mr. Lincoln was someseven years ago at his father’s home in Lexington, Kentucky. One of our Rebelsurgeons has a father residing in Westmoreland County, New York while anotherhas a mother and sister residing in Cecil County, Maryland, my old home and theland of my birth.

On Wednesdaymorning last, having sent over the last of our 200 wounded, we bid adieu toSecessia, glad once more to hear Yankee Doddle and to see our blue-clad fellowsoldiers. We traveled once more from the extreme right to the extreme left ofour lines, through camps innumerable. All seemed happy as larks, enjoying thebright warm weather and the welcome rest after their arduous toils. The army,as far as I can judge, is just as effective and courageous and is able andwilling to fight another battle just as they were before the late fight. Icould detect no signs of decimation or demoralization and if we could only geta fair chance at the enemy in an open field, I have no doubt we can whip them.

Source:

Letter from Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins, 88thPennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Lancaster Daily Evening Express(Pennsylvania), May 20, 1863, pgs. 1-2

December 27, 2024

Something more stirring than common in the wind: Delaying the Federal Advance Along the Nashville Pike

After nearly three days of constant fighting in the daysbefore the Battle of Stones River, Captain George Knox Miller of the 8thConfederate Cavalry recalled an instance where two of the combatants finally hadenough and called a truce.

The scene was along Stewart’sCreek near LaVergne, Tennessee. “One of my boys, John C. Duncan, a very jovialfellow, singled out a Yankee and the two fired away at each other for overthree hours, all this time in speaking distance,” Miller said. “They abusedeach other heartily and incessantly. At last John bantered the other man tocease firing and make an exchange of newspapers. After considerable parleying,the proposal was agreed to, an armistice arranged, and the firing ceased. Johnsucceeded in getting possession of a Confederate newspaper and walked down tothe creek. The Yankee did likewise. While the two pickets were thus amusingthemselves, the whole Yankee army about the place came to look on. Newspaperswere exchanged and compliments passed.”

Written mere days after thebattle to his future wife Celestine McCann who then was residing in Equality in AndersonCounty, South Carolina, Captain Miller’s account provides an in-depth perspectiveof Wheeler’s delaying actions along the Nashville Pike on December 26-28. Theletter, part of a broader unit history Captain Miller provided to the AlabamaDepartment of Archives and History, is copied from the files of Stones RiverNational Battlefield.

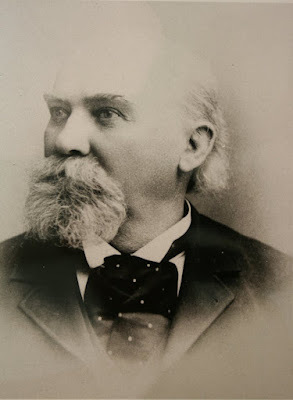

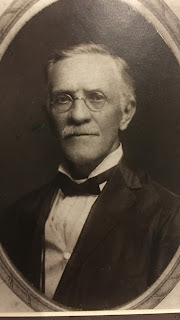

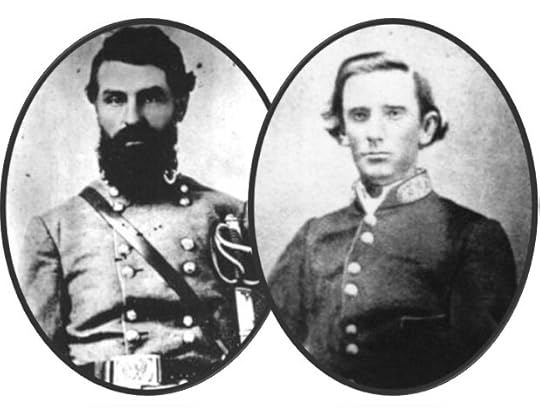

Captain George Knox Miller commanded Company A of the 8th Confederate Cavalry during the Stones River campaign. The regiment, consisting of six companies from Alabama and four from Mississippi, was formed into the 8th Confederate Cavalry and served under General Joseph Wheeler. Captain Miller dropped out of the study of law at the University of Virginia when Virginia seceded, and returned home to Talladega and enlisted in Captain Bowie's cavalry company which he later led.

Captain George Knox Miller commanded Company A of the 8th Confederate Cavalry during the Stones River campaign. The regiment, consisting of six companies from Alabama and four from Mississippi, was formed into the 8th Confederate Cavalry and served under General Joseph Wheeler. Captain Miller dropped out of the study of law at the University of Virginia when Virginia seceded, and returned home to Talladega and enlisted in Captain Bowie's cavalry company which he later led. January 10, 1863

South of Murfreesboro, Tennessee

I spent a quietChristmas in our camp at Stewart’s Creek, not choosing to engage in the sportsand pastimes resorted to by our officers generally: drinking, gambling, horseracing, etc. I felt much than I had in several day and found pleasure enough inthat feeling. The next morning, I was still weak but wanted to be with my boysin their work and accordingly reported for duty.

We had a drill in the morning butabout 12 o’clock, heavy firing in the direction of LaVergne warned us that theenemy was not spending the holiday in festivities at Nashville. The cannonadinggradually drew nearer and an order came for what of the brigade was then incamp to come up to LaVergne in all haste. We were soon in the saddle and a trotof five miles soon brought us to LaVergne.

In front of that place, we foundthe enemy. It was now 3 o’clock and as they did not retire, as when merely outforaging, we knew pretty well that something more stirring than common was inthe wind.

Our regimentwas sent forward to the left of the pike to support the 3rd AlabamaCavalry which the enemy was pressing pretty vigorously. After going about a mile,we dismounted and left our horses under the protection of a hill and dashed forwardas skirmishers. A quarter of a mile brought us upon the enemy well-concealed ina cedar thicket. They opened upon us at about 150 yards. Now the order came forus to charge. Forward we dashed, over two fences and to within 30 yards of theYankees. We had as hot a little brush as one would want on a December day.

The Yanks were well-posted andit was near dark. They had the advantage of the field where we marched.Besides, their uniforms were so near the color of the cedars behind which theyfought that it was almost impossible for our men to see them. For nearly anhour we fought them, each man to his tree. I was on foot and walked a little inadvance of our line to find better ground for some of the boys who were verymuch exposed. When kneeling at the foot of a tree and drawing a bead on a bigrascal, a Minie ball grazed my trousers just above the knee. It cut the orangecord I wear for a stripe but did no other damage. Bark from stricken trees fellinto my eyes from time to time but I was not hurt in the least.

Finding the enemy wellsupported, we withdrew inch by inch, until it grew so dark that we could notdistinguish one object from another. Nothing but the flash of the random gunremained to tell us that the enemy had taken his position for the night. Wecould see in the distance the whole horizon lit by his campfires. It requiredno ghost to tell that Rosecrans had begun his long-expected advance fromNashville. And this view was confirmed by the fact that all day long we hadheard heavy cannonading to our left on the Nolensville Pike showing his advancewas in heavy column on each road.

Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8th Confederate Cavalry

Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8th Confederate Cavalry The next day being our turn incourse to go on picket, our regiment returned to camp to prepare rations. Wegot in about 10 o’clock, cooked until 12, laid ourselves down to be thoroughlydrenched with rain and aroused by the bugle call at 3 a.m. At daylight, westarted for the field and had just thrown out pickets when the enemy advanced uponus. I commanded the pickets on the extreme left.

As the enemy advanced, we fellback slowly, skirmishing all the way. Our forces on the right between me andthe turnpike having fallen back faster than I anticipated threw me for a timein the rear of a large body of the enemy. There I had a full view of the heavycolumn as it rolled down the pike- infantry, cavalry, and artillery. I saw onewhole regiment of their cavalry mounted on white horses. I was so close that Icould distinctly hear the commands of the different officers.

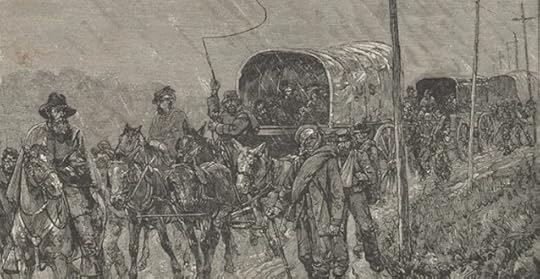

General Joseph Wheeler's delaying actions along the Nashville Pike slowed the Federal long enough to give his commanding general Braxton Bragg enough time to gather the dispersed portions of the Army of Tennessee to offer battle.

General Joseph Wheeler's delaying actions along the Nashville Pike slowed the Federal long enough to give his commanding general Braxton Bragg enough time to gather the dispersed portions of the Army of Tennessee to offer battle. Stewart’s Creek is a drivingstream with very steep banks and our intention was to cross it at the bridge onthe pike. But when we reached this point, we found that our artillery hadalready crossed over and General Wheeler had destroyed the bridge. The enemy’sartillery was then raking the pike. Fortunately, we found a narrow path leadingto a ford about a quarter of a mile above the burnt bridge. We barely had timeto cross when the enemy came close upon our heels. Night came on and weestablished a picket line for the night on the south bank of the creek onground where a few hours before our camps had been. They were now removedbackwards in the direction of Murfreesboro.

A cold, drenching rain hadfallen all day and there was another cheerless night before us. My squadronformed the second relief and was to stand four hours from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. Iwas lying on a wet blanket, nearly freezing, when I was called to go on duty. Iimmediately aroused my wet and sleepy boys. The enemy’s picket line was on theopposite side of the creek and so near that we could hear them in lowconversation.

While I passed along the bank,going from one post to another, one of their pickets fired on me not more than50 yards distant. His aim was only a little wide of my head and I called to himthat he had little to do! I moved on. Our high position gave us a full view ofthe enemy’s camp. As far as the eye could reach to the North, to the wholeearth seemed covered with their fires from which a murmur rose, like a swarm ofbees.

I slipped down to within 30yards of the burnt bridge and could hear a hundred hammers on the pontoonsbeing laid to replace it. I was certain that the morning would bring hot workfor us, but nothing disturbed the scene except occasional shots exchanged betweenour pickets and the enemy’s sharpshooters. The sun came out as genial as on aspring day this last Sunday in December 1862.

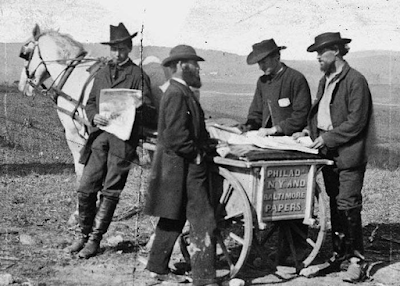

The trade in newspapers between the two armies at in Tennessee was surprisingly strong and frequent. It was not unusual for Rosecrans' headquarters to obtain copies of the Murfreesboro Daily Rebel Banner or Chattanooga Daily Rebel within a few days of publication. Likewise, Bragg's headquarters often had issues of the latest Nashville, Louisville, and even Cincinnati newspapers. Censorship was almost unheard of and no doubt the staffs of both armies gleaned much useful information about their enemies from the "open source" literature made available by the enlisted men engaging in this illicit trade in newspapers.

The trade in newspapers between the two armies at in Tennessee was surprisingly strong and frequent. It was not unusual for Rosecrans' headquarters to obtain copies of the Murfreesboro Daily Rebel Banner or Chattanooga Daily Rebel within a few days of publication. Likewise, Bragg's headquarters often had issues of the latest Nashville, Louisville, and even Cincinnati newspapers. Censorship was almost unheard of and no doubt the staffs of both armies gleaned much useful information about their enemies from the "open source" literature made available by the enlisted men engaging in this illicit trade in newspapers. I took advantage of a house nearthe creek. There I stood and viewed the Yankee horde as it filled the woods andopen fields in front of me. At 11 o’clock, my relief came on again and I postedmy boys behind trees and fences where for hours they amused themselves shootingat Yankee sharpshooters on the other side of the creek. One of my boys, John C.Duncan, a very jovial fellow, singled out a Yankee and the two fired away ateach other for over three hours, all this time in speaking distance. Theyabused each other heartily and incessantly. At last John bantered the other manto cease firing and make an exchange of newspapers. After considerable parleying,the proposal was agreed to, an armistice arranged, and the firing ceased. Johnsucceeded in getting possession of a Confederate newspaper and walked down tothe creek.

The Yankee did likewise. Whilethe two pickets were thus amusing themselves, the whole Yankee army about theplace came to look on. Newspapers were exchanged and compliments passed. Theenemy proved to be Federal Kentuckians. They asked many questions about friendsand acquaintances in our army. At sundown, all returned to their places. But,true to their instincts, the foe took advantage of John Duncan’s armistice tothrow sharpshooters over the creek and drive our pickets from a hill whichcommanding the road. We soon double-teamed and sent them back Gilpin style.

Captain Frederick Garternicht of the 84th Illinois provided a Federal perspective on this exchange of newspapers on December 28th. "After firing an hour or two, apparently with no effect on either side, the boys commenced laughing and hallooing to the Secesh. At first, they exchanged epithets and threw slang at each other; finally, they asked us if we had any papers to exchange. I had a Louisville Journal and was willing to exchange; we stopped firing and Alexander Beck went to the stream to affect the exchange. He wrapped his paper around an ear of corn and threw it over. The Secesh threw his but it came to shore then rolled back into the river. The Secesh grabbed another one (the latest they had) and it also fell into the river. Beck fished it out and got it though in very damp condition. Secesh, after expressing his regret at the accident, told Beck that his colonel wished him to tell his captain to do as they did in Virginia and not fire on the pickets. To this I consented, and we talked together until Captain [Alexander] Pepper with his Co. K relieved us." [To see full post, click here to read "A Nice Little Game of Balls Played Over Our Heads: With the 84th Illinois at Stones River."]

To learn more about the initial fighting along the Nashville Pike in the days leading up to the Battle of Stones River, please check out this post:

The LaVergne Skirmish [December 27]: Captain John H. James of the 26th Ohio

Source:

Letter from Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8thConfederate Cavalry, Stones River National Battlefield Regimental Archives

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

December 26, 2024

Days of Constant Vigilance and Fighting: The 8th Texas Cavalry and the Opening of the Stones River Campaign

General John Wharton’s cavalrybrigade, tasked with guarding the left flank of the Army of Tennessee’sposition in middle Tennessee, saw plenty of action in the opening days of theStones River campaign as remembered by Chaplain Robert F. Bunting of the 8thTexas Cavalry.

“The old year, freighted withmomentous events, is numbered with the mighty past,” he wrote to the editor ofthe Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph. “It’s blended hopes and fears, itsmingled sighs and tears, its victories and defeats are all among things thatwere. 1863 has been born amid the stirring scenes which will have a prominentrecord in history. The second battle of Murfreesboro has been fought, a glorioustriumph has followed our arms and the sounds of victory were sounding forthalong the lines of the Army of Tennessee. That brilliant achievement was thelast legacy which the departing year could give to our bleeding country.”

In this excerpt from ChaplainBunting’s lengthy account of the campaign, he describes the fighting whichbegan on Christmas Day 1862 and only increased with intensity over the next twodays as the 8th Texas Cavalry grappled with the advance of GeneralAlexander McCook’s Right Wing.

Pennsylvania-born Robert Franklin Bunting went off to war in 1861 with the storied 8th Texas Cavalry. Bunting not only served the spiritual needs of Terry's Texas Rangers but also took on the role of regimental historian. His lengthy letters back home are some of the best Confederate documentation of the Stones River campaign.

Pennsylvania-born Robert Franklin Bunting went off to war in 1861 with the storied 8th Texas Cavalry. Bunting not only served the spiritual needs of Terry's Texas Rangers but also took on the role of regimental historian. His lengthy letters back home are some of the best Confederate documentation of the Stones River campaign. Shelbyville, Tennessee

January 6, 1863

Editor Telegraph,

The old year,freighted with momentous events, is numbered with the mighty past. It’s blendedhopes and fears, its mingled sighs and tears, its victories and defeats are allamong things that were. 1863 has been born amid the stirring scenes which willhave a prominent record in history. The second battle of Murfreesboro has beenfought, a glorious triumph has followed our arms and the sounds of victory weresounding forth along the lines of the Army of Tennessee. That brilliantachievement was the last legacy which the departing year could give to ourbleeding country.

On Christmasabout 11 o’clock, the enemy’s battle line slowly advanced upon our left wingwhich had been protected by General Wharton’s brigade for over a month. Hisline extended from the Wilson and Winstead Pikes to the Nolensville Pike, someseven miles. During all this time, the duty of picketing the Wilson Pike hadbeen assigned to Lieutenant [William] Ellis with Co. G. About noon, his picketswere driven in and he was soon compelled to abandon his reserve stand and fallback towards Nolensville. The line of the enemy being composed of infantry,cavalry, and artillery could only be impeded by our cavalry.

The brigadehad early been ordered to the front and during the afternoon the Rangersskirmished very heavily with the enemy for several hours. Observing theircoolness and individual daring when charging upon the enemy, one could not butfeel that they were engaged in holiday amusement rather than the introductionto a great battle. Towards evening, quiet reigned and we returned to camp.

Lt. Arthur Pue and his wife

Lt. Arthur Pue and his wifeCo. G, 8th Texas Cavalry

Fridaymorning, couriers from our pickets reported the enemy still advancing in heavyforce. His battleline was extended and compact. He had early reachedNolensville some three miles below our camp. It was not certain the enemy wasmaking a general advance and the brigade was sent out to skirmish and disputehis way. The Rangers were today conspicuous for the determination and couragewith which they fought. At one time, they were in the hottest place they havelately found, but the danger only seemed to develop their coolness andgallantry.

During theday, Captain White’s battery of two guns did splendid execution and greatlycontributed to our success. Some 15 Rangers are on detached service in thisbattery. Under Lieutenant Arthur Pue, they are efficient artilleryman. King’sGeorgia Battery today abandoned a gun and it fell into the hands of the enemy.It was lost through pure cowardice. Slowly the enemy advanced his line. Ourcasualties increased: Lieutenant A.H. McClure of Co. E was killed while J.H.Glasco and P.C. Pybas of Co. C were slightly wounded. Samuel Dennis of Co. K ismissing while Colonel Harrison had his horse shot from under him. Captain [Gustave] Cookwas temporarily stunned by his horse falling. Sergeant Major John M. Claibornehad both himself and horse knocked down by a cannon ball.

About 2 o’clock,it was evident our camp was in danger. Hastily, tents were struck and the trainmoved beyond Triune. Here the wagons remained until morning and then set outfor Murfreesboro. It was a very rainy and disagreeable night. As darkness cameon, it was found that the enemy lay within a few hundred yards of the housewhich had been occupied as headquarters by General Wharton.

General Sterling Alexander Martin Wood (left) and General John A. Wharton conducted a well-conducted delaying action near Triune on Saturday, December 27, 1862, holding McCook's wing to an advance of just seven miles.

General Sterling Alexander Martin Wood (left) and General John A. Wharton conducted a well-conducted delaying action near Triune on Saturday, December 27, 1862, holding McCook's wing to an advance of just seven miles. Saturday wasgloomy. From the exposure of the night and want of food, the men felt illyprepared for a renewal of the fight. But daylight opened the ball again. Bythis time, General [Sterling A.M.] Wood’s infantry brigade had come to ourassistance and with a battery or two they supported our charges. The infantrydid but little fighting. Our cavalry was constantly engaged during theforenoon. Triune being situated in a rolling country the ground was adapted tothis work. The maneuvering was skillful, and everywhere the enemy was met byour gallant boys. General Wharton and staff were constantly moving and inperson he directed the movements. The cavalry of the enemy was becoming moredaring but the infantry was close by providing support. This rendered ourcharges dangerous for whenever his cavalry was pressed, they would fall backand draw us upon the infantry.

With their long-rangeguns, we were in their power. In the afternoon, when we had retired beyondTriune, his batteries opened on us. It was observed today that the Rangers werealways nearest the enemy and under the heaviest fire. They can oftener get intoa fight with him than any other cavalry. It was now the evident policy of ourgenerals to draw the enemy on and mass our troops at Murfreesboro, hence ourskirmishing and falling back. It was a day of constant vigilance and fighting.

Our lastengagement of the day was heavy and one and a half miles this side of Triune.Our loss increased. During the evening, a very heavy rain fell which made thedirt roads very mirey, yet the train plod on through mud and water until lateat night when it camped near the Salem Pike. The sun set clear and the nightwas very frosty, but the dry cedars furnished good fires and thus the exposurewas neutralized. The cavalry camped near the train. The infantry had mostlypreceded us from Triune. It was a serious trip for them.

DaylightSunday morning [December 28] found the train ready to move and by the end apike 12 o’clock found us within five miles of Murfreesboro. The warm sun andbalmy air contrasted most favorably with yesterday’s gloom and rain. We allanticipated a few hours’ rest in preparation for the coming fight, but scarcelyhad the horses been unsaddled and the wagons started out for forage, theblankets and clothing spread out to dry, before a courier came dashing alongwith the announcement that the enemy was still upon us and within two miles by anotherTriune road.

All wascommotion again. The cavalry hastened to the rear and the train moved towardsMurfreesboro. It proved to be a false alarm although he was on our track sixmiles to the rear. The Rangers spent the night near his advance while the traincamped near town. On Sunday night, every available main and horse was madeready for the coming battle.

To read more about the opening phases of the Stones River campaign, please check out these posts:

Capturing the Gun at Knob Gap with the 15th Wisconsin

Charles Barney Dennis at Stones River Pt. 1

Source:

Letter from Chaplain Robert Franklin Bunting, 8thTexas Cavalry, Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Texas), January 1863

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

December 23, 2024

Twice Captured and Stripped: Father Stephan's Bad Day Among the Confederate Cavalry

While perusing issues of the Journal& Courier from Lafayette, Indiana recently, I came across thisfascinating little story of a chaplain’s experience during the Battle of StonesRiver. It took a bit of digging to find out that the central character of thisstory was none other than Father Joseph Andrew Stephan, who at the time of thebattle was leading St. Boniface Church in Lafayette.

“The adventures of our worthyfriend Father Stephan in the recent battle of Murfreesboro furnish aninteresting chapter in the history of the great fight,” the Journal &Courier reported in their January 20, 1863, issue. “On Wednesday morning,in company with two other gentlemen, he started out on a mission of mercy andunconsciously got into the Rebel lines and was made a prisoner. He was taken tothe headquarters of the Rebel General [Joseph] Wheeler when, after stating hisvocation, he was released and furnished with a mule to regain our lines.”

“While pursuing his way union-ward,the mule landed him gently into a middle puddle and upon examination he foundthat a cannonball from one of our batteries had deprived the quadruped of twoof his pedestals,” the paper continued. “While deploring this accident, a partyof concealed Rebels again made a prisoner of him by whom he was treatedshamefully. They stripped him almost to a state of nudity, beat and kicked himmost unmercifully, at the same time relieving him of everything in the way ofvaluables.”

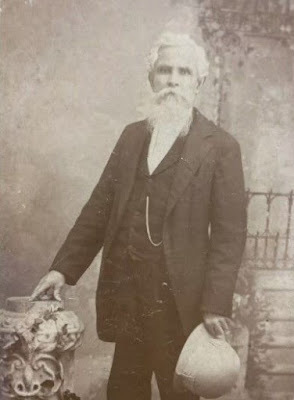

Father Joseph Andrew Stephan of St. Boniface Parish in Lafayette, Indiana, shown here much later in life, was "very indignant" at the treatment he received from Confederate cavalrymen during the Battle of Stones River when the Hoosier priest was captured twice upon the battlefield. Rather than just live with the indignity, he threw his shoulder to the wheel and joined the army in May 1863.

Father Joseph Andrew Stephan of St. Boniface Parish in Lafayette, Indiana, shown here much later in life, was "very indignant" at the treatment he received from Confederate cavalrymen during the Battle of Stones River when the Hoosier priest was captured twice upon the battlefield. Rather than just live with the indignity, he threw his shoulder to the wheel and joined the army in May 1863. “Our troops coming in sight, theRebels, forcing the worthy chaplain to accompany them, beat a retreat,” thestory continued. “But upon Father Stephan giving out from sheer exhaustion,they mounted him upon a modern Rosinante without saddle or bridle and in thismanner reached the Rebel lines. He was eventually released and his entrée intoNashville, minus several important articles of wearing apparel, is described asanything but agreeable. He was very indignant at the treatment he receivedwhich, however, is on par with their previous actions.”

A few days later, no less apersonage that General William S. Rosecrans telegraphed the Bishop of theDiocese of Cincinnati asking that Father Stephan might be allowed to return tothe army. “Father Stephan is not only an invaluable aid in the hospital but isa first-class civil engineer,” the Journal & Courier reported. “He wasattached in this capacity to the staff of one of the revolutionary generals inBaden in 1848 and won some distinction.”

Joseph Andrew Stephan’s rootsstretched back to the Gissingheim in the Duchy of Baden-Wurttemberg where hewas born November 22, 1822, to Greek and Irish parents. Educated at Freiburgand Karlsruhe, he became an instructor in civil engineering at one of the universitiesbut became seriously ill and emigrated to the United States after the failedrevolution where completed his theological studies in Cincinnati. By theoutbreak of the Civil War, he was leading St. Boniface Parish in Lafayette. Anearly supporter of the war effort, Father Stephan lent his influence and gavehis support by both making speeches and encouraging enlistments, but also byvisiting his parishioners in the field. That’s how he came to his misadventuresat Stones River.

Perhaps still “indignant”at his recent treatment by the Confederate cavalry and flattered by Rosecrans’request (Rosey’s brother was also a Catholic priest in the Diocese ofCincinnati), Father Stephans was commissioned as a hospital chaplain on May 18,1863, and served until the end of the war, mustering out July 15, 1865. Hisobituary stated that “during the Civil War, Monsignor Stephan served as chaplainwith the forces of General Sheridan,” a fellow Catholic.

“He was one of the promoters ofCatholic missionary work among the Indians and in 1884 was appointed Directorof the Indian Mission by Cardinal Gibbons,” the obituary continued. “He waseminently successful in this work as is attested by the fact that during thisperiod he secured for the maintenance and support of the mission between $4-5million from the government and private sources. He was greatly loved by theIndians and his death will be mourned by them.” Monsignor Stephan passed away ofpneumonia September 12, 1901, in Washington, D.C. at the age of 79. He isburied at the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament Cemetery in Bensalem,Pennsylvania.

Sources:

“Father Stephans,” Lafayette Journal & Courier(Indiana), January 20, 1863, pg. 3

“Father Stephens,” Lafayette Journal & Courier(Indiana), January 24, 1863, pg. 3

“Funeral of Mgr. Stephan,” Washington Post (District ofColumbia), September 16, 1901, pg. 8

December 22, 2024

The Troops Need Rest Very Much: A Confederate Reporter Writes After Nashville

Writing from West Point, Mississippi along the Mobile &Ohio Railroad, a reporter from the Memphis Daily Appeal assured theeditors that despite the defeat at Nashville, he was hopeful that a period orrest and reorganization would bring the Army of Tennessee back into fightingtrim.

“The largerportion of the army is now at Tupelo where it was some two and a half years ago,”he wrote. “The Memphis & Charleston Railroad is still occupied by ourtroops from Corinth to Tuscumbia. Whether our army will go into winter quarterswhere it is now or not, I am unable to say. The troops need rest very much andthe probability is that they will be quartered at once.”

Speaking withsoldiers wounded at Franklin and brought into Mississippi for medicaltreatment, he found them “all cheerful and speak of the fight at Franklin asone of the more desperate of the war. Many of these troops will soon recoverfrom their wounds and be ready again to confront the foe.”

But the situation at Tupelo was dire- despite the reporter's glossy appraisal, the Army of Tennessee had been well-nigh wrecked by its campaign in Tennessee. The army had been reduced to roughly 15,000 infantrymen and as Thomas Connelly wrote "fewer than half were still equipped or considered effective. A large part of the army's artillery had been captured, abandoned, or destroyed. Some 13,000 small arms were missing and wagon transportation had been annihilated on the long march. By January 14, when Beauregard arrived at Tupelo, the army was practically without food, still had no winter clothing, and had few blankets to withstand the unusually cold Mississippi winter."

The same day Beauregard arrived at Tupelo, General John Bell Hood, the army's commander, asked to be relieved of command of the army. Two days later, Richmond agreed and General Richard Taylor took command.

Originally published in the MemphisDaily Appeal (then being produced in Montgomery, Alabama), this letter wasrepublished in the January 27, 1865, edition of the Alabama Beacon fromGreensboro, Alabama.

By the time the once proud Army of Tennessee rolled into camp at Tupelo in early January 1865, its ranks had dwindled to less than 20,000 men, most of them suffering from a lack of winter clothing and equipment. One of its veterans, Sam Watkins, recalled that the "Army of Tennessee had degenerated to a mob. We were pinched by hunger and cold. The rains and sleet and snow never ceased falling from the winter sky while the winds pierced the old, ragged grayback Rebel soldier to his very marrow. The clothing of many were hanging around them in shreds of rags and tatters while an old-fashioned slouch hat covered their frozen ears."

By the time the once proud Army of Tennessee rolled into camp at Tupelo in early January 1865, its ranks had dwindled to less than 20,000 men, most of them suffering from a lack of winter clothing and equipment. One of its veterans, Sam Watkins, recalled that the "Army of Tennessee had degenerated to a mob. We were pinched by hunger and cold. The rains and sleet and snow never ceased falling from the winter sky while the winds pierced the old, ragged grayback Rebel soldier to his very marrow. The clothing of many were hanging around them in shreds of rags and tatters while an old-fashioned slouch hat covered their frozen ears."

West Point, Mississippi

January 12, 1865

Editors Appeal,

As I amstopping here for a few hours, I propose to give you a line or two.

The largerportion of the army is now at Tupelo where it was some two and a half years ago.[see "Braxton Bragg and the Tupelo Revival."] The Memphis & Charleston Railroad is still occupied by ourtroops from Corinth to Tuscumbia. Whether our army will go into winter quarterswhere it is now or not, I am unable to say. The troops need rest very much andthe probability is that they will be quartered at once.

The roads arein a wretched condition, almost impassable. This being the case, it will be impossiblefor the enemy to advance upon us under two months at least. During this time,our army can be reorganized and repleted in numbers to 40,000-50,000 or evenmore which will prevent [General George] Thomas from executing his coveted planin the spring- that of aping Sherman and plunging his hireling horde throughMississippi and Alabama to the Gulf. This is now said to be his campaign forthe spring.

To preventhim, our country should arouse itself being now and that time, put every mancapable of bearing arms in the field to oppose him. It will not do forMississippi and Alabama to be overrun and held by the enemy as our armies nowdraw their supplies from these states. The Yankees, being aware of this fact,will put forth their whole force to overrun them as soon as the condition ofthe roads will admit of an advantage.

The woundedfrom Corinth are now being shipped through this place to Columbus, Mississippiand other points in the rear. Dr. Tuttle informs me that he has sent 550yesterday on one train and expects more today. The most of them are slightlywounded and were brought away from Franklin and Nashville before our army fellback. They are all cheerful and speak of the fight at Franklin as one of themore desperate of the war. Many of these troops will soon recover from theirwounds and be ready again to confront the foe.

In the defeatof our army near Nashville and the retreat from the state of Tennessee, ourprincipal loss was in artillery. This is quite serious, but as we have plentyof guns captured from the enemy in previous engagements with him, we can affordit. More anon.

Sources:Letter from Memphis, Alabama Beacon (Alabama), January27, 1865, pg. 1

Connelly, Thomas L. Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee, 1862-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971, pg. 513

December 19, 2024

Jesus Will Take Me Home: Lt. Col. Canfield's Final Days

Herman Canfield was born July 29, 1817, in Canfield Township,Mahoning County, Ohio, the youngest son of Herman Canfield and his wife Fitie. Hegained his education in the common schools of his community and entered Kenyon Collegein 1834 where he became proficient in both Greek and Latin. In 1838, heembarked on the study of law and was admitted to the bar in 1841. By 1845, hemoved to Medina and joined his law practice with that of his older brotherWilliam and soon was appointed clerk of the common pleas court.

In 1848, he married Sarah Ann MarthaTreat and the couple, ardent abolitionists and possessing a deep faith in God, assistedwith the local Underground Railroad while Herman devoted his legal talents to defendingfellow Ohioans accused of breaking the Fugitive Slave Act. The couple joined St.Paul’s Episcopal Church where Herman became superintendent of the Sundayschool.

Herman and Sarah Ann "Martha" Canfield.

Herman and Sarah Ann "Martha" Canfield. Originally a Whig, Canfieldjoined the Republican Party upon its formation and served in the Ohio Senatefrom 1855-1862. In 1860, he was appointed Trustee of the Ohio State IdioticAsylum “in which position he faithfully and devotedly served until his death,spending the last hours of the night preceding his departure from Camp Chase[in February 1862] with the superintendent of the institution,” his obituarysaid.

ColonelCanfield “saw the South was marshaling for resistance to law” and upon thefiring upon Fort Sumter, “his soul was most deeply stirred and at the firstcall of the president for volunteers, he was strongly moved by the desire toaid in preserving his beloved land from its peril,” his obituary noted. He tooka leading role in raising troops in Mahoning County and in October 1861,Governor William Dennison commissioned him lieutenant colonel of the 72ndOhio Volunteer Infantry.

It took monthsfor the 72nd Ohio to fully organize, but it left the state inFebruary 1862 for its first camp in Paducah, Kentucky and by March 1862 was incamp at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. Colonel Ralph P. Buckland of the 72ndOhio was placed in command of the brigade which elevated Colonel Canfield to commandof the regiment. “He soon exhibited rare qualities as a commanding officer,enforcing good discipline while winning the warm love of his soldiers andinspiring them with confidence in his ability to lead them successfully tovictory or death,” his obituary continued.

On April 6,1862, the test would come and for Lieutenant Colonel Herman Canfield, it would bethe end.

After being wounded, Lieutenant Colonel Herman Canfield of the 72nd Ohio was carried behind the field officers' tents in the 72nd Ohio camp and given medical treatment. The wound, however, proved to be mortal. This article details what is known of Colonel Canfield's last two days alive. You can walk on these same grounds today at Shiloh National Military Park as I did back in 2021.

After being wounded, Lieutenant Colonel Herman Canfield of the 72nd Ohio was carried behind the field officers' tents in the 72nd Ohio camp and given medical treatment. The wound, however, proved to be mortal. This article details what is known of Colonel Canfield's last two days alive. You can walk on these same grounds today at Shiloh National Military Park as I did back in 2021. Charles Treat, Colonel Canfield’sbrother-in-law, witnessed the 72nd Ohio going into action on Sundaymorning and provided the following account of the action and wounding of thecolonel. “Early on Sunday morning, scattering firing was heard in the directionof Prentiss’s division which soon came nearer,” Treat stated. “Shortly after 8o’clock, the 70th Ohio was called out, formed in line, and advancedfiring. The 72nd immediately formed in line in front of its camp andadvanced towards the creek. They had marched about 20 rods to the brink of ahollow when they saw the enemy’s infantry not 20 rods distant, filling theravine and coming down over the opposite ridge. They had crossed the creek onthe bridges built for the march of our army and came in unobserved by ourforces. The opposing forces immediately drew up in line of battle facing eachother and commenced a heavy fire of musketry.”

“The executionwas murderous,” he continued. “At every volley, our men fell in numbers and theeffect on the enemy was at least equally as great. The wounded, as fast as theyfell, were taken to the rear of the regimental camp, and placed on hay that hadbeen hastily thrown on the ground for their reception. For more thanthree-quarters of an hour, this desperate conflict continued, the firing beingas rapid as the men could load and fire. Neither side gave any sign ofretiring, both parties fighting with desperation. At the end of that time, thefiring ceased on both sides and the enemy fell back for more ammunition.”

“During thefirst fight with the enemy, Colonel Canfield continually rode up and down theline of the regiment, cheering on his men. Just at the close of the firstfight, as he was in the act of turning to ride back along the line, a Minieball entered his breast through the right arm hole of his vest, passed alongthe whole distance and penetrating the right lung and then passed out the leftside, tearing a ghastly hole. He fell from his horse and was carried to the rearby some of his men who placed him on some hay thrown in the rear of the fieldofficers’ tents.”

Three men who treated Colonel Canfield's wound from left to right: Surgeon John B. Rice, Assistant Surgeon William M. Kaull, and Captain Charles G. Eaton

Three men who treated Colonel Canfield's wound from left to right: Surgeon John B. Rice, Assistant Surgeon William M. Kaull, and Captain Charles G. Eaton Treat came to thecolonel’s side and remained with him until the end. Regimental surgeon JohnRice, assisted by Captain Charles G. Eaton, examined the wound and somelint was placed on the wound. “He lay apparently dead until Treat poured some brandyand water into his mouth when he opened his eyes and said with difficulty, ‘Rightlung, bleeding inwardly.’

In themeantime, a subsequent attack on the Federal line caused the 72ndOhio to retreat. Colonel Buckland had notified Dr. Rice that the line waslikely to give way “and when the order came, we took with us all our woundedand the 8 men who had been wounded the Friday previous and as many sick fromthe field,” Rice recalled. “Some were placed in wagons, some on horses ormules, and some were carried off in litters.” Colonel Canfield, knowing thathis wound was fatal, had expressed a wish that his brother-in-law would takehim home to his family. As the regiment started to retreat around him, Charles “expresseda fear that he would not be able to comply with his brother’s request, to whichColonel Canfield calmly replied, “Never mind, Charley, Jesus will take me home.”

Treat need not have feared ashelp soon arrived. Colonel Canfield wasplaced on a stretcher and carried to the rear by Treat, Sergeant Major Orin England, and two privates into a ravine. “They followed the line of the ravineamid a hailstorm of bullets that rattled all around them until a gully wasreached and partially protected them,” Treat remembered. “Finding they were cutoff from the regiment by the enemy, the little party followed the gully to thecreek which they forded at one place and crossed at another across a log and athird time on a temporary bridge. They waded through the mud until the banks ofthe Tennessee were reached about 3 miles above Crump’s Landing.”

Sergeant Major Orin O. England was one of the four litter bearers who carried Colonel Canfield miles back to safety near Crump's Landing. England was later commissioned first lieutenant of Co. C and served on General Ralph Buckland's staff later in the war.

Sergeant Major Orin O. England was one of the four litter bearers who carried Colonel Canfield miles back to safety near Crump's Landing. England was later commissioned first lieutenant of Co. C and served on General Ralph Buckland's staff later in the war. The partyspent a miserable night along the riverbank. “Here they lay all night which waspitchy dark in a storm of wind, rain, thunder, and lightning. Treat and hiscompanions kept the rain off the wounded colonel’s face by holding out ablanket over him all night. About 50 men of various regiments, most of themsick and wounded, were on the riverbank having escaped from the battlefield.Captain [John H.] Blinn and [Co. E] Captain Eaton of the 72nd werethere with about 20 men, all they could find of their companies. They had beencut off from their regiment and retreated in the direction of Crump’s Landing.”

At dawn, the party set out forCrump’s Landing where Colonel Canfield was placed aboard an old barge thatSurgeon Thomas W. Fry of the 11th Indiana had converted into ahospital. “During the day, we received some 50 of the wounded who wandered some5, 6, or 8 miles through the woods,” Fry recalled. “Among them was brought on alitter Lieutenant Colonel Canfield of Ohio.” Canfield’s wound was finallytreated but it was too late. “He was shot through the lungs and died about darkon Monday,” Dr. Fry stated.

Charles Treat recalled thataround noon the colonel “became partially conscious and died at nearly 7 o’clockon Monday evening. Before he became unconscious, he inquired repeatedly inrelation to the progress of the fight and once made the remark, ‘I have facedthe enemy and fell.’ A little before his death, Treat informed him that we hadwon the victory; Canfield slightly raised his hand as if to show that heunderstood.” His obituary noted that “during all these hours of consciousness,he expressed no misgivings as to the wisdom of his choice, no regrets as to hisearly fall. He had said, in view of the possibility of his fall, that if it pleasedGod, he would that it might be in the last battle of this terrible rebellionwhen the work of the soldier was done.”

Unbeknownst to all, ColonelCanfield’s wife Martha had arrived at Pittsburg Landing on Sunday anddiscovered his husband soon after his death. Surgeon Fry recalled that Canfield’s“wife came up on Monday or Tuesday, not knowing he was wounded, and found hisdead body on our barge.” No doubt stunned at the loss, she, along with herbrother Charles, accompanied her husband’s body back home to Ohio, stoppingfirst at Cairo before moving on to Cincinnati, Columbus, Tiffin, and finally Medina.

Lt. Col. Herman Canfield Gravestone

Lt. Col. Herman Canfield GravestoneMedina, Ohio

The Mahoning Registeropined upon his loss that “we have given up one of our best, an honest man, aman of talent, a good, exemplary citizen, a safe counsellor, a true patriot,and an able soldier. Mr. Canfield was a lover of letters, a lover of nature,and learning. His heart had a warm side towards humanity, a reformer in sympathy,warm in his friendship.” A large number of citizens from Mahoning County metthe train at Grafton to escort the colonel’s body back to the family home inMedina. “On the following days prior to internment, the house was thronged byvisitors desirous of taking a last view of him who had fallen when battling forthe rights of their common country,” the Cleveland Morning Leader stated.

A public funeral was held onMonday April 14, 1862, and in which Colonel Canfield’s remains, escorted to thegrave by a dozen of his fellow attorneys, were laid to rest at Spring GroveCemetery in Medina. Thinking back on their work with the Underground Railroad,Widow Canfield resolved to continue her husband’s work by setting up an orphans’asylum for formerly enslaved children in Memphis, Tennessee and operated it forthe rest of the war.

Sources:

“Battle of Pittsburg Landing: The 72nd in the Fight,”account of Charles Treat, Daily Toledo Blade (Ohio), April 14, 1862, pg.2

“Jesus Will Take Me Home,” Marysville Tribune (Ohio),October 8, 1862, pg. 4

Letter from Surgeon John B. Rice, 72nd Ohio. Dee,Christine. Ohio’s War: The Civil War in Documents. Athens: OhioUniversity Press, 2006, pg. 69

Letter from Surgeon Thomas W. Fry, 11th IndianaVolunteer Infantry, Lafayette Journal & Courier (Indiana), April 25,1862, pg. 2

“Lieut. Col. Canfield,” Mahoning Herald (Ohio), May 1,1862, pg. 2

“The Late Lieut. Col. Canfield- Action of His FellowCitizens- Funeral Obsequies,” Cleveland Morning Leader (Ohio), April 18,1862, pg. 3

History of Medina County, Ohio. Chicago:Baskin, Battey, Historical Publishers, 1881, pg. 336

December 17, 2024

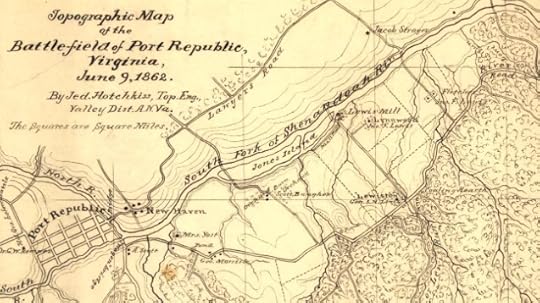

A Hoosier at Port Republic

Looking back on the events of the Battle of Port Republic, Private Elliott Winscott of the 7th Indiana laid the blame for his regiment's misfortunes on one man: Colonel Samuel Sprigg Carroll. In particular, he called into question Carroll's decision making on the Sunday afternoon on June 8, 1862.

"On Sunday, we were within 6 miles of Port Republic and the cavalry under the command of Captain Keughn of Shields’ staff was sent ahead to drive the enemy from the bridge that spans the Shenandoah Rover opposite the town," he noted. "The work was entrusted to a faithful officer and nobly did he discharge his duty, driving the enemy away and firing the bridge. Had he been left to use his own discretion, as he ought to have been, the bridge would have been destroyed and saved our defeat. But no sooner had General Carroll heard what had been done when he ordered the fire put out, and two pieces of short-range brass guns were ordered forward together with our brigade to support them. The purpose was to drive the enemy back and hold the bridge. The general must have been greatly deceived in the strength of the enemy or thought they were arrant cowards that would run at the first appearance of a few Yankees, or he would never have given such orders for the enemy at the least calculation were 20,000 strong while our force did not exceed 1,500."

Winscott was correct, and Carroll's decision set the stage for the fight on the following day where two brigades of General James Shields' division were overwhelmed when attacked by Stonewall Jackson's army.

"

There never was so unnecessary a sacrifice of life since the beginning of time," Winscott concluded. "No general was ever known to make an attack against such unequal numbers with so little show of accomplishing any good, and but for the want of sound judgment, all this sad casualty to life and the cause we are defending might have been avoided."PrivateWinscott’s account of the Battle of Port Republic first saw publication in theJune 27, 1862, edition of the Dearborn County Democratic Registerpublished in Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

Camp near Luray, Page Co., Virginia

June 11, 1862

I doubt notthat any news could have been more startling to the citizens of our state andparticularly to some of those in Dearborn County than that which has recentlyflashed across the electric wires announcing the sad disaster to a portion ofShields’ division, composed partly of the 7th Indiana regiment. Itis true we have met with a reversion in which several precious lives have beenlost, causing anguish of heart to friends at home, but our defeat has been a dearlybought victory to our enemies.

Probably it wasfortunate to our boys that we met the enemy when we did, for although we lostsome noble fellows in that battle, many more lives must inevitably have beensacrificed by fatiguing marches we were making order to give them fight. It isdeath, anyhow, to a soldier in Shields’ division and it were far better that heshould fall on the battlefield by the hands of the enemy than to eek out amiserable existence after being broken down by long marches.

We wereenjoying one of those temporal reposes which are so seldom given us after along march when on Saturday last, we were ordered to strike our bivouacks and beprepared to march at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. We drew short rations for twodays, started, and marched till about midnight, a portion of the way over stonyroads, and the balance through a miry swamp. Then we stopped and spread ourblankets for sleep, having gone about 13 miles. At 3 o’clock in the morning, wewere again awake and put in motion again. The advancing column consisted of the7th Indiana in front, the 1st Virginia, and the 84thand 110th Pennsylvania following together, with a company or two ofcavalry, all of which constituted the Fourth Brigade of General Shields’division commanding by General Samuel S. Carroll.

On Sunday,which has nearly always been an unfortunate day for making an attack, we werewithin 6 miles of Port Republic and the cavalry under the command of CaptainKeughn of Shields’ staff was sent ahead to drive the enemy from the bridge thatspans the Shenandoah Rover opposite the town. The work was entrusted to afaithful officer and nobly did he discharge his duty, driving the enemy awayand firing the bridge. Had he been left to use his own discretion, as he oughtto have been, the bridge would have been destroyed and saved our defeat. But nosooner had General Carroll heard what had been done when he ordered the fire putout, and two pieces of short-range brass guns were ordered forward togetherwith our brigade to support them. The purpose was to drive the enemy back andhold the bridge.

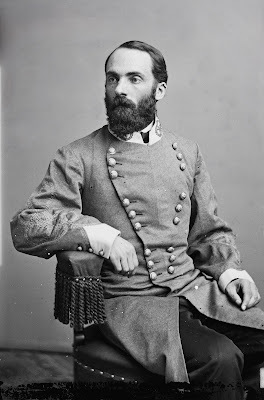

Colonel Samuel S. Carroll

Colonel Samuel S. Carroll8th O.V.I.

The generalmust have been greatly deceived in the strength of the enemy or thought theywere arrant cowards that would run at the first appearance of a few Yankees, orhe would never have given such orders for the enemy at the least calculationwere 20,000 strong while our force did not exceed 1,500. There were morebelonging to the brigade, but most all of the 84th and 110thPennsylvania fell out, some from exhaustion, and others doubtless for want ofnerve.

Port Republicis situated on an island formed in the Shenandoah River. That part of the riverbetween us and the town is not large and not bridged and the town is reached byfording the stream. One of our pieces was crossed into the town and the otherleft on this side. Our artillery opened upon the enemy’s battery which repliedin intervals as if merely making a formal resistance until our brigade wasbrought into range. Then they opened upon us with about 6 batteries of 5-6pieces each from the opposite end of the bridge.

The enemy’sguns were planted on the brow of the hill fronting the river commanding theroad we had to come through for two miles at least, and for about an hour and ahalf, they poured shot, shell, and canister into our ranks that seemed to fallaround and in the ranks almost as thick as hail in an April shower. To allthis, we could only feebly resist with two pieces of artillery. The wholetransaction looked, to a sensible mind, like an act of folly of foolhardiness.The folly of the move was seen by our general and a retreat ordered, but notuntil we had lost 8 men killed and several wounded out of our regiment. CaptainJesse Armstrong’s company escaped with but two casualties: James Gattenby receiveda slight contusion on the head and I was bruised in the side by a splinter froma rail knocked off by a bursting shell.

Pvt John Russell

Pvt John RussellCo. K, 7th Indiana Infantry

The regimentretreated from the field about two and a half miles in good order, the enemyfollowing up our retreat with a few pieces of cannon but without much effect.About 30 of the boys in Co. K were engaged and all behaved like brave men, butparticular credit is due to William Merrill, Thomas Williams, James Lambertson,A.J. Connelly, and William Ripking for volunteering their services to bring upa cannon from under the fire of the enemy’s guns that the artillerymen had beencompelled to abandon because they had broken the tongue out of the carriage. Thesemen, with a few others from different companies of our regiment, went backnearly a mile in the direction of the enemy and brought out the piece withtheir own hands.

Anotherinstance of personal bravery: the color bearer was wounded by a shell andsuffered the colors to trail on the ground when Thomas Grogan, another ofCaptain Armstrong’s boys, stepped forward, grabbed the flagstaff, and handinghis gun to the color bearer, unfurled the colors again to the breeze andtriumphantly bore them from the field. If brave conduct meets with its justreward, these men should receive for their bravery something more than apassing compliment from those whose duty it is to reward men for meritoriousconduct.

After we hadfallen back under the shelter of an adjacent wood and remained for a shortspace of time, the Third Brigade [Colonel Erastus B. Tyler] came to our reliefand the two brigades went back about 3 miles, stationing themselves along ahillside in a thick wood. But by this time, Blenker’s division had engaged theenemy on the opposite side of the river out of our reach but within the soundof their cannons. Heavy cannonading from both forces were heard by us all thatafternoon. The result is unknown further than we learned from Rebel prisonerstaken the next day that Jackson’s forces had driven Blenker’s division back 3miles with heavy losses on both sides.

During thecourse of Sunday night, the enemy crossed the bridge in large force andscattering a few men in a wheatfield, stationed the others in different positionsin front to the left of us. Monday morning came and brought with it the clashof resounding arms. The enemy’s cavalry made their appearance in the road andour artillery opened on them, bringing on a general engagement. The 7thIndiana was posted on the extreme right and Co. K was deployed to skirmish inthe field and had the first man wounded that day.

The skirmishers had fired but afew shots when the regiment was brought into contact with three of the enemyregiments. The enemy poured volley after volley into our ranks for threequarters of an hour and yet with their vastly superior numbers, they had togive way, our regiment driving them back to the river. The battle now commencedin earnest, the enemy came pouring out of the woods on our left in numbersalmost innumerable, making it impossible for our forces to withstand theircharge and we had to give way, retreating under their fire and leaving manydead and wounded upon the field.

The 7th Indiana hadto make the attack, and when our forces were compelled to retire, she coveredthe retreat. The engagement on the part of the artillery lasted 6 hours and theinfantry just 3 hours and all, even those who had fought in European wars, saythat the firing was the sharpest they ever witnessed. Colonel [James] Gavin hadhis horse shot from under him. Lt. Colonel [John F.] Cheek was with the boysuntil compelled by sickness to leave the field. He should not have been therefor the reason he had been unwell for several days before the battle. Our losswas heavy but the enemy lost two to our one.

The 7th Indiana lost23 killed and 143 wounded and missing. None of the killed were of Co. K. CaptainArmstrong, who commanded this company, was in all the fight at his post.Lieutenant [James F.] Vaughn was along with the company and through hiscoolness has the credit of saving many a soldier from an untimely grave. Onlyabout 25 of Co. K were engaged in the fight on Monday and the casualty wasgreat for the number engaged. The reason that there was not any more of thecompany in the fight was because they had no shoes to wear on the march.

There never was so unnecessary asacrifice of life since the beginning of time. No general was ever known tomake an attack against such unequal numbers with so little show ofaccomplishing any good, and but for the want of sound judgment, all this sadcasualty to life and the cause we are defending might have been avoided.

Source:

Letter from Private Elliott Winscott, Co. K, 7thIndiana Volunteer Infantry, Dearborn County Democratic Register (Indiana), June27, 1862, pg. 2

December 13, 2024

Go in on your own hook, boys: With the 16th Indiana at Vicksburg

As the Federal army tightened the noose around Vicksburg onMay 21, 1863, Captain James R.S. Cox of the 16th Indiana had anopportunity to observe General Ulysses S. Grant up close and personal.

Cox was atop aridge with Generals Stephen Burbridge and A.J. Smith when he saw “GeneralGrant, smoking as usual, walking slowly along the ridge, paying no attention tothe sharpshooters who are feeling for him,” he wrote. “Some newspapers deem himincompetent to fill the position, but the soldiers of his army swear by him.They know that the campaign, thus far and under great difficulties, has beenconducted successfully. I had formed an idea from the description that he was awhiskey barrel on legs but found myself greatly in error. Paying littleattention to dress, he usually wears a stand-up collar with cap and coat muchthe worse for wear. He seems a plain unassuming man, whether studying his maps oras is his custom, smoking, walking up and down with his hands behind him, graveand thoughtful, becoming one filling his high position.”

Captain Cox’sin-depth description of the skirmishing on May 21st at Vicksburgfirst saw publication in the June 12, 1863, edition of the Dearborn CountyDemocratic Register published in Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

As the 16th Indiana's skirmish line approached the Confederate works at Vicksburg on May 21, 1863, the Hoosiers traded barbs and bullets with the gray-clad defenders, their favorite phrase being "Here's your mule!" The Hoosiers came away impressed with the Vicksburg defenses and Colonel Thomas J. Lucas was convinced a frontal assault would be a "useless sacrifice." The following day's assault would bear out Lucas's prediction.

As the 16th Indiana's skirmish line approached the Confederate works at Vicksburg on May 21, 1863, the Hoosiers traded barbs and bullets with the gray-clad defenders, their favorite phrase being "Here's your mule!" The Hoosiers came away impressed with the Vicksburg defenses and Colonel Thomas J. Lucas was convinced a frontal assault would be a "useless sacrifice." The following day's assault would bear out Lucas's prediction. Headquarters, 10th Division, 13th Corps

(near Vicksburg, Mississippi, May 1863)

On Monday [May 18, 1863], theadvance of Grant’s army passing over Black River and driving in rear guards andskirmishers bivouacked within cannon range of the vaunted Sevastopol of the NewWorld. After its long mud impediment, like one of the Southern alligatorssuddenly awakened from its torpor, this army had marched nearly 200 miles,passing completely in rear of the foe. In 20 days, it had fought and gained 8battles, captured 72 pieces of artillery, the capitol of the state, 10,000prisoners, and so many small arms that for want of transportation, thousands ofthem were burnt.

Division after division arrivedduring the night and took up their position so when the sun rose on Wednesday morning[May 20] it found the Rebel forces completely encircled: Sherman’s army corpson the right, McPherson in the center, McClernand on the left with McArthur andhis men in possession of Warrenton on the Mississippi. The enthusiasm commonwith recruits had long since passed away from the men which compose this army.Here were regiments who spoke with pride of battlefields as far back as Belmontwhile many bore inscribed upon their banners the proud word Shiloh.

The Rebels had spent a year inpreparing to meet the shock and now the gathering forces of the Federal armyseemed locked round the doomed city in a death struggle for supremacy of theSouthwest. Every state in the Northwest is represented here, and they seem toknow that before them are strong works with desperate men to man them. A spiritof grim earnestness is seen on every countenance from the general in his tentto the skirmisher watching his chance for a shot over the walls of the fort.

General Stephen G. Burbridge

General Stephen G. BurbridgeIn the morning, the roar ofcannons unceremoniously awoke us and after breakfast, we started out to see aday’s work, General [A.J.] Smith permitting me to accompany him while the companyremained behind has headquarters guards. Passing a short distance up a ravine,horses were hitched, it being unhealthy for them on the top of the ridge. Uponreaching it, we found our gallant Brigadier General Stephen G. Burbridge at work with the 17th Ohio Battery. He said hehad been at work since daylight and had dismounted some of the enemy’s cannons.Burbridge is a noted artillerist. At Champion Hill, he fired the shot thatkilled General Lloyd Tilghman. The Rebel general had just sighted a gun andstepped back when a piece of exploding shell hit him on the head and made onetraitor less.

On the point, the eye takes in aportion of the Rebel works. We almost involuntarily draw a long breath as weperceive the number and strength of their forts. Each of their smaller worksare constructed open to the rear with a front and apron at the sides which areconnected with similar works by rifle pits. There are three or four of thesesmall forts and then a large one along the whole range of hills.

Burbridge sighted a gun at apoint where the wheels could be seen in the large fort in front of McPherson. Acolumn of smoke 200 feet high showed that he had exploded a caisson or limber.It created quite a confusion and we could see them trying to take away theartillery horses through a glass. We watched one fellow tugging away at thehalter of an obstinate mule until shells commenced dropping too thick, then hebroke. The bullets of their sharpshooters were singing over us as we lay in theshade on the green hillside, and our thoughts of May parties at home were disturbedby some of them coming unpleasantly near.

Some of the boys of the 6thMissouri Cavalry came out to see the fun. That regiment has a great reputation.They have been driven from their homes by guerillas, had their homes burned,friends murdered, wives and little ones exposed to inclement weather. Feelingthemselves to be the avengers of blood, seldom troubling themselves with prisoners,they show no mercy and feel no remorse. In trying to rally a wavering line atthe Arkansas Post fight, Major [Samuel] Montgomery, in plain view on horseback,shook his fist at the yelling scoundrels in the fort in his excess of wrath.

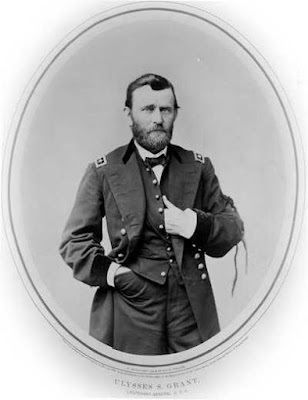

"He seems a plain, unassuming man, whether studying his maps or as is his custom smoking, walking up and down with his hands behind him, grave and thoughtful," wrote Captain James R.S. Cox of his army commander at Vicksburg. "History will decide whether as the servant of a nation and the leader of great armies he possessed the requisite abilities which constitute a great general."