Something more stirring than common in the wind: Delaying the Federal Advance Along the Nashville Pike

After nearly three days of constant fighting in the daysbefore the Battle of Stones River, Captain George Knox Miller of the 8thConfederate Cavalry recalled an instance where two of the combatants finally hadenough and called a truce.

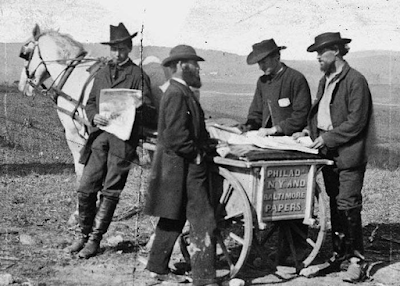

The scene was along Stewart’sCreek near LaVergne, Tennessee. “One of my boys, John C. Duncan, a very jovialfellow, singled out a Yankee and the two fired away at each other for overthree hours, all this time in speaking distance,” Miller said. “They abusedeach other heartily and incessantly. At last John bantered the other man tocease firing and make an exchange of newspapers. After considerable parleying,the proposal was agreed to, an armistice arranged, and the firing ceased. Johnsucceeded in getting possession of a Confederate newspaper and walked down tothe creek. The Yankee did likewise. While the two pickets were thus amusingthemselves, the whole Yankee army about the place came to look on. Newspaperswere exchanged and compliments passed.”

Written mere days after thebattle to his future wife Celestine McCann who then was residing in Equality in AndersonCounty, South Carolina, Captain Miller’s account provides an in-depth perspectiveof Wheeler’s delaying actions along the Nashville Pike on December 26-28. Theletter, part of a broader unit history Captain Miller provided to the AlabamaDepartment of Archives and History, is copied from the files of Stones RiverNational Battlefield.

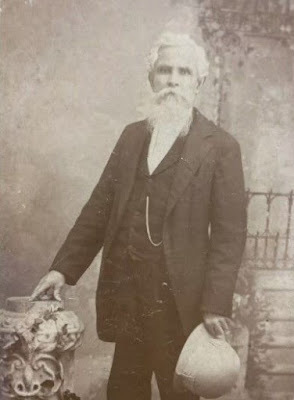

Captain George Knox Miller commanded Company A of the 8th Confederate Cavalry during the Stones River campaign. The regiment, consisting of six companies from Alabama and four from Mississippi, was formed into the 8th Confederate Cavalry and served under General Joseph Wheeler. Captain Miller dropped out of the study of law at the University of Virginia when Virginia seceded, and returned home to Talladega and enlisted in Captain Bowie's cavalry company which he later led.

Captain George Knox Miller commanded Company A of the 8th Confederate Cavalry during the Stones River campaign. The regiment, consisting of six companies from Alabama and four from Mississippi, was formed into the 8th Confederate Cavalry and served under General Joseph Wheeler. Captain Miller dropped out of the study of law at the University of Virginia when Virginia seceded, and returned home to Talladega and enlisted in Captain Bowie's cavalry company which he later led. January 10, 1863

South of Murfreesboro, Tennessee

I spent a quietChristmas in our camp at Stewart’s Creek, not choosing to engage in the sportsand pastimes resorted to by our officers generally: drinking, gambling, horseracing, etc. I felt much than I had in several day and found pleasure enough inthat feeling. The next morning, I was still weak but wanted to be with my boysin their work and accordingly reported for duty.

We had a drill in the morning butabout 12 o’clock, heavy firing in the direction of LaVergne warned us that theenemy was not spending the holiday in festivities at Nashville. The cannonadinggradually drew nearer and an order came for what of the brigade was then incamp to come up to LaVergne in all haste. We were soon in the saddle and a trotof five miles soon brought us to LaVergne.

In front of that place, we foundthe enemy. It was now 3 o’clock and as they did not retire, as when merely outforaging, we knew pretty well that something more stirring than common was inthe wind.

Our regimentwas sent forward to the left of the pike to support the 3rd AlabamaCavalry which the enemy was pressing pretty vigorously. After going about a mile,we dismounted and left our horses under the protection of a hill and dashed forwardas skirmishers. A quarter of a mile brought us upon the enemy well-concealed ina cedar thicket. They opened upon us at about 150 yards. Now the order came forus to charge. Forward we dashed, over two fences and to within 30 yards of theYankees. We had as hot a little brush as one would want on a December day.

The Yanks were well-posted andit was near dark. They had the advantage of the field where we marched.Besides, their uniforms were so near the color of the cedars behind which theyfought that it was almost impossible for our men to see them. For nearly anhour we fought them, each man to his tree. I was on foot and walked a little inadvance of our line to find better ground for some of the boys who were verymuch exposed. When kneeling at the foot of a tree and drawing a bead on a bigrascal, a Minie ball grazed my trousers just above the knee. It cut the orangecord I wear for a stripe but did no other damage. Bark from stricken trees fellinto my eyes from time to time but I was not hurt in the least.

Finding the enemy wellsupported, we withdrew inch by inch, until it grew so dark that we could notdistinguish one object from another. Nothing but the flash of the random gunremained to tell us that the enemy had taken his position for the night. Wecould see in the distance the whole horizon lit by his campfires. It requiredno ghost to tell that Rosecrans had begun his long-expected advance fromNashville. And this view was confirmed by the fact that all day long we hadheard heavy cannonading to our left on the Nolensville Pike showing his advancewas in heavy column on each road.

Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8th Confederate Cavalry

Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8th Confederate Cavalry The next day being our turn incourse to go on picket, our regiment returned to camp to prepare rations. Wegot in about 10 o’clock, cooked until 12, laid ourselves down to be thoroughlydrenched with rain and aroused by the bugle call at 3 a.m. At daylight, westarted for the field and had just thrown out pickets when the enemy advanced uponus. I commanded the pickets on the extreme left.

As the enemy advanced, we fellback slowly, skirmishing all the way. Our forces on the right between me andthe turnpike having fallen back faster than I anticipated threw me for a timein the rear of a large body of the enemy. There I had a full view of the heavycolumn as it rolled down the pike- infantry, cavalry, and artillery. I saw onewhole regiment of their cavalry mounted on white horses. I was so close that Icould distinctly hear the commands of the different officers.

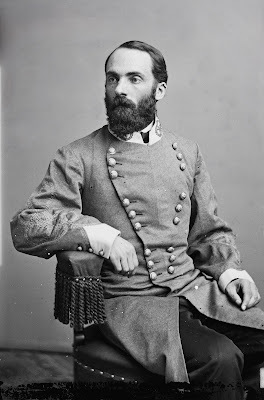

General Joseph Wheeler's delaying actions along the Nashville Pike slowed the Federal long enough to give his commanding general Braxton Bragg enough time to gather the dispersed portions of the Army of Tennessee to offer battle.

General Joseph Wheeler's delaying actions along the Nashville Pike slowed the Federal long enough to give his commanding general Braxton Bragg enough time to gather the dispersed portions of the Army of Tennessee to offer battle. Stewart’s Creek is a drivingstream with very steep banks and our intention was to cross it at the bridge onthe pike. But when we reached this point, we found that our artillery hadalready crossed over and General Wheeler had destroyed the bridge. The enemy’sartillery was then raking the pike. Fortunately, we found a narrow path leadingto a ford about a quarter of a mile above the burnt bridge. We barely had timeto cross when the enemy came close upon our heels. Night came on and weestablished a picket line for the night on the south bank of the creek onground where a few hours before our camps had been. They were now removedbackwards in the direction of Murfreesboro.

A cold, drenching rain hadfallen all day and there was another cheerless night before us. My squadronformed the second relief and was to stand four hours from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. Iwas lying on a wet blanket, nearly freezing, when I was called to go on duty. Iimmediately aroused my wet and sleepy boys. The enemy’s picket line was on theopposite side of the creek and so near that we could hear them in lowconversation.

While I passed along the bank,going from one post to another, one of their pickets fired on me not more than50 yards distant. His aim was only a little wide of my head and I called to himthat he had little to do! I moved on. Our high position gave us a full view ofthe enemy’s camp. As far as the eye could reach to the North, to the wholeearth seemed covered with their fires from which a murmur rose, like a swarm ofbees.

I slipped down to within 30yards of the burnt bridge and could hear a hundred hammers on the pontoonsbeing laid to replace it. I was certain that the morning would bring hot workfor us, but nothing disturbed the scene except occasional shots exchanged betweenour pickets and the enemy’s sharpshooters. The sun came out as genial as on aspring day this last Sunday in December 1862.

The trade in newspapers between the two armies at in Tennessee was surprisingly strong and frequent. It was not unusual for Rosecrans' headquarters to obtain copies of the Murfreesboro Daily Rebel Banner or Chattanooga Daily Rebel within a few days of publication. Likewise, Bragg's headquarters often had issues of the latest Nashville, Louisville, and even Cincinnati newspapers. Censorship was almost unheard of and no doubt the staffs of both armies gleaned much useful information about their enemies from the "open source" literature made available by the enlisted men engaging in this illicit trade in newspapers.

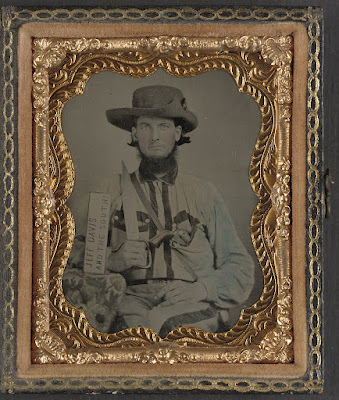

The trade in newspapers between the two armies at in Tennessee was surprisingly strong and frequent. It was not unusual for Rosecrans' headquarters to obtain copies of the Murfreesboro Daily Rebel Banner or Chattanooga Daily Rebel within a few days of publication. Likewise, Bragg's headquarters often had issues of the latest Nashville, Louisville, and even Cincinnati newspapers. Censorship was almost unheard of and no doubt the staffs of both armies gleaned much useful information about their enemies from the "open source" literature made available by the enlisted men engaging in this illicit trade in newspapers. I took advantage of a house nearthe creek. There I stood and viewed the Yankee horde as it filled the woods andopen fields in front of me. At 11 o’clock, my relief came on again and I postedmy boys behind trees and fences where for hours they amused themselves shootingat Yankee sharpshooters on the other side of the creek. One of my boys, John C.Duncan, a very jovial fellow, singled out a Yankee and the two fired away ateach other for over three hours, all this time in speaking distance. Theyabused each other heartily and incessantly. At last John bantered the other manto cease firing and make an exchange of newspapers. After considerable parleying,the proposal was agreed to, an armistice arranged, and the firing ceased. Johnsucceeded in getting possession of a Confederate newspaper and walked down tothe creek.

The Yankee did likewise. Whilethe two pickets were thus amusing themselves, the whole Yankee army about theplace came to look on. Newspapers were exchanged and compliments passed. Theenemy proved to be Federal Kentuckians. They asked many questions about friendsand acquaintances in our army. At sundown, all returned to their places. But,true to their instincts, the foe took advantage of John Duncan’s armistice tothrow sharpshooters over the creek and drive our pickets from a hill whichcommanding the road. We soon double-teamed and sent them back Gilpin style.

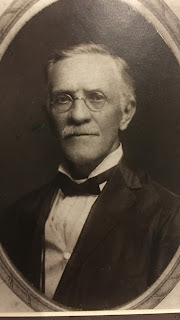

Captain Frederick Garternicht of the 84th Illinois provided a Federal perspective on this exchange of newspapers on December 28th. "After firing an hour or two, apparently with no effect on either side, the boys commenced laughing and hallooing to the Secesh. At first, they exchanged epithets and threw slang at each other; finally, they asked us if we had any papers to exchange. I had a Louisville Journal and was willing to exchange; we stopped firing and Alexander Beck went to the stream to affect the exchange. He wrapped his paper around an ear of corn and threw it over. The Secesh threw his but it came to shore then rolled back into the river. The Secesh grabbed another one (the latest they had) and it also fell into the river. Beck fished it out and got it though in very damp condition. Secesh, after expressing his regret at the accident, told Beck that his colonel wished him to tell his captain to do as they did in Virginia and not fire on the pickets. To this I consented, and we talked together until Captain [Alexander] Pepper with his Co. K relieved us." [To see full post, click here to read "A Nice Little Game of Balls Played Over Our Heads: With the 84th Illinois at Stones River."]

To learn more about the initial fighting along the Nashville Pike in the days leading up to the Battle of Stones River, please check out this post:

The LaVergne Skirmish [December 27]: Captain John H. James of the 26th Ohio

Source:

Letter from Captain George Knox Miller, Co. A, 8thConfederate Cavalry, Stones River National Battlefield Regimental Archives

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

Daniel A. Masters's Blog

- Daniel A. Masters's profile

- 1 follower