The Best of Friends and Most Determined of Enemies: A Pennsylvania Surgeon Among the Confederates After Chancellorsville

Ordered across the Rappahannock after the conclusion of theBattle of Chancellorsville, Surgeon John W. Rawlins of the 88thPennsylvania might have expected a grim task ahead of him. What surprised thePennsylvanian was the courtesy and kindness with which he was treated by hisConfederate hosts.

Arriving atthe field hospital set up at Salem Church, Surgeon Rawlins recalled the warmfriendships that soon developed with his counterparts in gray. “During our stayof four days and four nights at this church and in its vicinity, we had a greatmany Rebel visitors from the generals down with whom we freely expressedopinions, discussing politics and the war freely,” he wrote. “We were treatedwith much courtesy and invariably with politeness. We had the pleasure ofmeeting surgeons from Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia,some of whom had been college mates of ours in Philadelphia, and others werewell acquainted with many of our former friends. Our social evenings at SalemChurch with the Rebel surgeons seemed more like the reunion of well-triedfriends after a long separation. We shook hands and parted the best of friendsbut the most determined of enemies.”

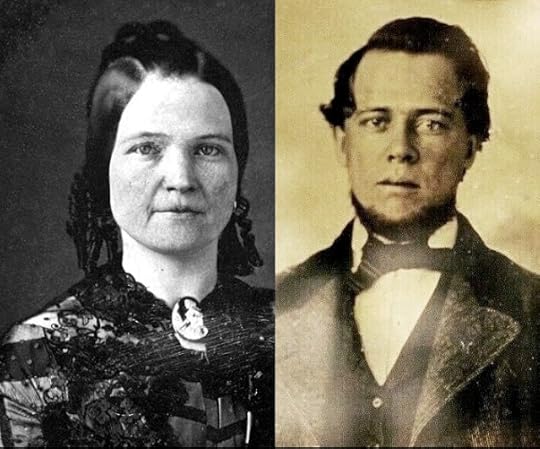

Among thesurgeons he met was Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, the younger brother of MaryTodd Lincoln. “I showed him a likeness (on a $10 greenback which by the way isa very true likeness) of his distinguished brother-in-law,” Rawlins noted. “Dr.Todd remarked that he considered the “circumstance no credit and no discredit.”Someone suggested that he should send Mrs. Lincoln a letter; he declined butsaid we “might give his respects.”

Surgeon Rawlins’remarkable letter first saw publication in the May 20, 1863, edition of the LancasterDaily Evening Express published in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

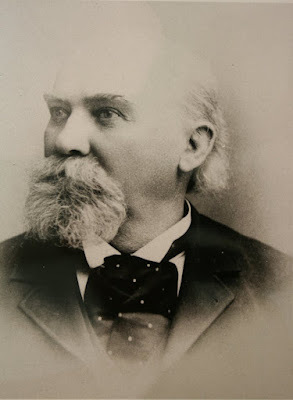

Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins of the 88th Pennsylvania was comfortably settling into camp when orders came for him along with a half dozen other surgeons to recross the Rappahannock and provide care for wounded Federal soldiers. Rawlins ended up at Salem Church, the scene of vicious fighting on May 3, 1863. Rawlins speaks little of the medical tasks he performed, focusing instead on the friendships that developed between the Federal and Confederate surgeons. "We shook hands and parted the best of friends and but the most determined of enemies," he noted.

Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins of the 88th Pennsylvania was comfortably settling into camp when orders came for him along with a half dozen other surgeons to recross the Rappahannock and provide care for wounded Federal soldiers. Rawlins ended up at Salem Church, the scene of vicious fighting on May 3, 1863. Rawlins speaks little of the medical tasks he performed, focusing instead on the friendships that developed between the Federal and Confederate surgeons. "We shook hands and parted the best of friends and but the most determined of enemies," he noted.

Camp in the pines, Virginia

May 14, 1863

During theafternoon of the May 6, 1863, we had another thunderstorm, accompanied by heavyrains, which made our camping place that night very muddy and unpleasant. Butfortunately, I succeeded in obtaining possession of an outhouse partly filledwith hat which I converted into a hospital for the night, furnished a drylodging place for some 10-15 guests.

The next day,May 7th, we encamped under shelter tents near our present locationand on the 8th, we pitched tents and prepared to make ourselves comfortable.But while I was sitting by a warm fire in my little camp stove between 5 and 6o’clock, drying my feet and congratulating myself upon the creature comfortswhich I was about to enjoy, I received an order to proceed immediately withinstruments and report to Dr. A. of the U.S. Army at Banks’ Ford. I would gowith a flag of truce within the enemy’s lines to attend our wounded on thebattlefield. In a few minutes, I was on the road and was joined at corpsheadquarters by six other surgeons. We proceeded on our lonely, devious, anddark road in pursuit of science or rather practice under difficulties.

After beingconducted from one line of pickets to another, we got lost, but after discoveringa farmhouse in the distance, we determined to go there and obtain a guide or remainthe balance of the night. Fortunately, we found Dr. A. there to whom we were toreport. We soon unburdened and fed our horses, unrolled our blankets on thefloor and went to sleep supperless. Next morning, after a good breakfastfurnished for us at 50 cents each by the kind farmer, we proceeded with ourboats and several wagonloads of supplies to Banks’ Ford, which, by courtesy ofthe Rebels whose pickets lined the south bank, allowed a number of us to cross.The balance was sent up to the United States Ford to cross over to thebattlefield of Chancellorsville. Three of us went on in advance, being guidedby a Rebel lieutenant colonel and a major on horseback who courteously carriedour field cases of instruments. We had to leave our horses on the north side ofthe river, not being able to get them over.

The first lotof wounded we came to numbered about 70 and occupied the barn of a man namedHogan. Our services being more urgently needed further on, we proceeded (afterstopping at several houses on the way where lots of 4-6 men were quartered) toSalem Church. This church is a brick building (of good size for a countrychurch) and is situated on the Plank Road leading from Fredericksburg toChancellorsville. Here we found nearly 100 of our wounded under the care of Dr.O. of the 121st New York who had been detained by the Rebels. [The121st New York under the command of Colonel Emory Upton reportedlylost 48 killed, 173 wounded, and 55 missing in the engagement near Salem Churchon May 3, 1863; 32 of the 55 missing were subsequently discovered to have beenkilled in action.]

During ourstay of four days and four nights at this church and in its vicinity, we had agreat many Rebel visitors from the generals down with whom we freely expressedopinions, discussing politics and the war freely. We were treated with muchcourtesy and invariably with politeness. We had the pleasure of meetingsurgeons from Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia, some ofwhom had been college mates of ours in Philadelphia [Jefferson Medical School], and others were wellacquainted with many of our former friends. Our social evenings at Salem Churchwith the Rebel surgeons seemed more like the reunion of well-tried friendsafter a long separation. Although our political sentiments were as wide asunderas the poles, I am sure both parties were highly gratified by the courteous,kind, and gentlemanly treatment received at each other’s hands. We shook handsand parted the best of friends but the most determined of enemies. I could notbut contrast their conversation and conduct with that of our Copperhead friendsof the North. The Rebel gentleman is a noble lion, the Copperhead a sneakinghyena.

On Sunday May10th, the Rebels having furnished is with an ambulance or two andseveral wagons, we placed in them about 50 of our best cases and we threesurgeons accompanied them on foot about four miles to Fredericksburg where theywere paroled and permitted to be sent across by General Barksdale. Having leftsufficient surgeons on the battleground, we proposed to cross over and rejoinour commands but General Barksdale would not permit us. I made a virtue ofnecessity and remarked to Barksdale that it was immaterial as we had so farbeen treated with great courtesy and anticipated nothing less than acontinuance of the same. He replied that there was a hotel in Fredericksburgwhere we might go, but knowing very well what poor fare and high charges wemight expect at a hotel in Rebeldom, I suggested that as we could still rendersome service at Salem Church, I would prefer to return there. He replied thathe had no objection to that.

So, we walkedback again accompanied a great part of the way by three Rebel soldiers whoentertained us with their account of the battle. We entered Fredericksburgabout an hour after their great General Stonewall Jackson died; he was woundedin both arms, only one of which he would suffer to be amputated. The Rebelssaid he was wounded accidentally by his own men who mistook him for a Unionofficer. They also state the cause of his death was pneumonia, but it is moreprobable, I think, that it was consequent upon his wounds and those woundsreceived from the enemy in battle as it was said he took command in person ofthe Stonewall Brigade after the death of Brigadier General Elisha Paxton. Inpassing through Fredericksburg, we witnessed the burial of a Rebel officer andthe brass band striking up a tune immediately behind us, we marched for thefirst time in our lives to Rebel music.

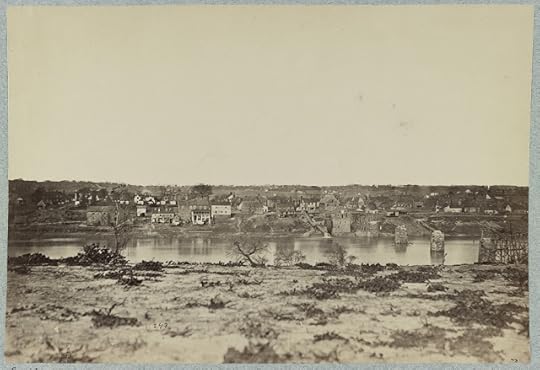

Fredericksburg, Virginia, in February 1863. By May, Surgeon Rawlins observed that "Fredericksburg is a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen. Many of the finest houses were deserted, the gardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers."

Fredericksburg, Virginia, in February 1863. By May, Surgeon Rawlins observed that "Fredericksburg is a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen. Many of the finest houses were deserted, the gardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers." Fredericksburgis a deserted city; there are but few women and children to be seen, but thosefew seemed quite interested in the appearance of “the Yankee officers.” A lotof well-dressed boys volunteered to show us the way down to the crossing whichwas opposite the Lacey House. Many of the finest houses were deserted, thegardens running wild with grass and beautiful flowers. We passed the celebratedMarye’s Heights which Sedgwick had the honor of taking but could not keep; wewalked back the same road many of the troops took tom escape at Banks’ Ford.

But, more unfortunate than us,they met a lion in their path in the shape of General [Cadmus] Wilcox’sbrigade, strongly posted behind breastworks made of planks taken from the PlankRoad. The Rebels say this was constructed after the battle, but I do notbelieve a word of it for the walls, windows, and ceiling of the brick churchare thickly strewn with the shreds of garments, letters to Federal soldiers,memorandum books, etc. All show plainly that a desperate contest occurred thereand the numerous graves provide still better proof. The Rebels say our troopsadvanced without throwing out skirmishers; the Rebel skirmishers quietlyretiring and leading the Federals right into the open space in front of theRebel lines.

The officerswe met with were nearly all intelligent and good-looking gentlemen. Some ofthem wore uniforms of coarse material, but all appeared to enjoy good healthand to be able to endure considerable service. But they did not endeavor todeny the fact that their men were all in the field, but they also assume ourconscripts won’t fight and that their veterans are more than a match for ours,having full confidence in their commanders. They estimate our so-called peacemen and Copperheads (Vallandigham, Woods, Sanderson, etc.) at their proper value.They know these truckling doughfaces of old and spur their sympathies as theywould the caress of a troublesome, fawning spaniel.

Mary Todd Lincoln and her younger brother Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, who at the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville was serving as the chief brigade surgeon for Brigadier General Paul Semmes' brigade of Georgians. When it was suggested that Dr. Todd send his older sister a letter, he declined but offered that the Federals "might give his respects" to Mrs. Lincoln.

Mary Todd Lincoln and her younger brother Dr. George Rogers Clark Todd, who at the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville was serving as the chief brigade surgeon for Brigadier General Paul Semmes' brigade of Georgians. When it was suggested that Dr. Todd send his older sister a letter, he declined but offered that the Federals "might give his respects" to Mrs. Lincoln. Among ourvisitors was Dr. [George Rogers Clark] Todd, chief surgeon of Semmes’ brigade.Dr. Todd is a brother of Mrs. President Lincoln. I showed him a likeness (on a$10 greenback which by the way is a very true likeness) of his distinguishedbrother-in-law. The Rebel officers all took a good look at the engraving. Dr.Todd remarked that he considered the “circumstance no credit and no discredit.”Someone suggested that he should send Mrs. Lincoln a letter; he declined butsaid we “might give his respects.” The last time he saw Mr. Lincoln was someseven years ago at his father’s home in Lexington, Kentucky. One of our Rebelsurgeons has a father residing in Westmoreland County, New York while anotherhas a mother and sister residing in Cecil County, Maryland, my old home and theland of my birth.

On Wednesdaymorning last, having sent over the last of our 200 wounded, we bid adieu toSecessia, glad once more to hear Yankee Doddle and to see our blue-clad fellowsoldiers. We traveled once more from the extreme right to the extreme left ofour lines, through camps innumerable. All seemed happy as larks, enjoying thebright warm weather and the welcome rest after their arduous toils. The army,as far as I can judge, is just as effective and courageous and is able andwilling to fight another battle just as they were before the late fight. Icould detect no signs of decimation or demoralization and if we could only geta fair chance at the enemy in an open field, I have no doubt we can whip them.

Source:

Letter from Surgeon John Windsor Rawlins, 88thPennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Lancaster Daily Evening Express(Pennsylvania), May 20, 1863, pgs. 1-2

Daniel A. Masters's Blog

- Daniel A. Masters's profile

- 1 follower