Daniel A. Masters's Blog, page 11

January 25, 2025

Fighting for the Honor of the Old Pine Tree State: The 4th Maine Battery at Cedar Mountain

Rolling into combat for the first time on the afternoon ofAugust 9, 1862, at Cedar Mountain, First Lieutenant Lucius Haynes of the 4thMaine Battery noted how the wounding of one of the men inspired the men of thebattery in the fight.

“We had notfired but three shots before Abel Davis of New Portland fell, wounded in theleg,” he wrote. “But this did not intimidate, it rather incited our boys torenewed valor. Now the firing of the enemy becomes indeed terrific; a perfectstorm of shell and solid shot pours in upon us from the front and right, comingapparently from six different Rebel batteries. We replied with spirit andundoubted effect. Every man stood bravely at his post- the officers workinghand-to-hand with the men, taking the places of those who had so nobly fallenat the posts. We had never been under fire before, but I think it can be saidof our Maine artillery not the first time under fire, that it did honor to thedear old Pine Tree State.”

LieutenantHaynes’ letter first saw publication in the August 29, 1862, edition of the KennebecJournal published in Augusta, Maine. It is worth noting that the 4th Maine Battery was equipped with 3-inch Rodman rifles at Cedar Mountain, having been issued these guns in late May 1862 and was under the command of Captain O'Neil W. Robinson.

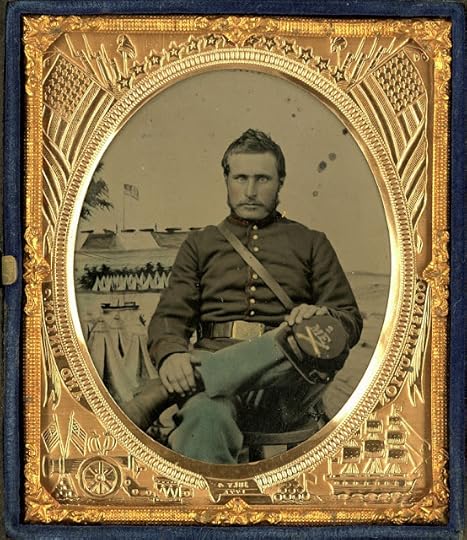

This image depicts an artillerist in the 2nd Maine Battery who also fought at Cedar Mountain but a little later in the engagement than the 4th Maine. Note the hat brass that calls out the battery number (2), ME for Maine, and crossed cannons symbolizing the artillery branch.

This image depicts an artillerist in the 2nd Maine Battery who also fought at Cedar Mountain but a little later in the engagement than the 4th Maine. Note the hat brass that calls out the battery number (2), ME for Maine, and crossed cannons symbolizing the artillery branch. Culpeper Courthouse, Virginia

August 14, 1862

Now that theexcitement and confusion of the late battle of Slaughter Mountain has somewhatsubsided, I will endeavor to give you a detailed description of its horrors andevents.

Prince’sbrigade, to which we were attached, was ordered to move from their camp onSaturday morning last at 11 o’clock. After a rapid march of about five milesduring which we were almost suffocated by heat and dust, we were halted in agrowth of woods about a quarter mile in width. Hardly had we recovered from thefatigue of our rapid movement, when the order came again ‘Forward!’ Emerging fromthe woods, we saw at once that we were really to engage the enemy. Already theshells were flying over our heads. The infantry moved off and took up theirposition on the left of the line of battle, which, consisting of our entirecorps (about 7,000 men) extended nearly a mile from east to west directly infront of Slaughter Mountain.

“Upon our arrival at the woods, General Prince placed CaptainRobinson under arrest for some reason, the exact nature of which was neverclearly understood but was generally supposed to be running by other troops andgetting out of place in the line. There was not a very good feeling existingbetween the General and Captain Robinson as was shown by a little incident thatoccurred that morning. After first harnessing up, the captain sent a lieutenantto the general asking for orders. The general very curtly replied, ‘When I haveorders for Captain Robinson, I will send them.’ This reply did not put thecaptain in the best of humor and perhaps had an effect on him during theremainder of the day. After about half an hour in the woods, the captain wasrelieved from arrest.” ~ History of the 4th Maine Battery LightArtillery

In front ofour line and about 30 rods in advance was a slight elevation. Here our battery,the 4th Maine, was ordered to take position and commence firing. Wewent into battle under a fire already becoming severe. But our boys were ascool as veterans. We were soon at work. We had not fired but three shots beforeAbel Davis of New Portland fell, wounded in the leg. But this did notintimidate, it rather incited our boys to renewed valor. Now the firing of theenemy becomes indeed terrific; a perfect storm of shell and solid shot pours inupon us from the front and right, coming apparently from six different Rebelbatteries. We replied with spirit and undoubted effect. Every man stood bravelyat his post- the officers working hand-to-hand with the men, taking the placesof those who had so nobly fallen at the posts. We had never been under firebefore, but I think it can be said of our Maine artillery not the first timeunder fire, that it did honor to the dear old Pine Tree State.

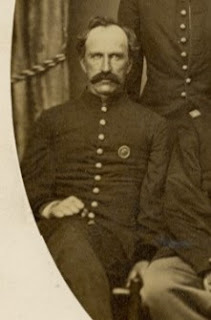

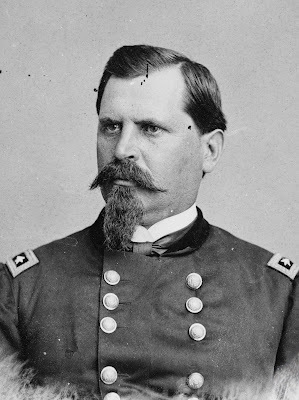

Captain O'Neil W. Robinson of the 4th Maine Battery sits in the chair with two of his fellow battery commanders of the 3rd Corps artillery brigade in this image taken at Brandy Station, Virginia. Artist Alfred Waud of Harper's Weekly stands at right. At Cedar Mountain, Captain Robinson found himself temporarily under arrest by his brigade commander General Henry Prince; Prince himself would be captured during the battle by a private in the 23rd Virginia.

Captain O'Neil W. Robinson of the 4th Maine Battery sits in the chair with two of his fellow battery commanders of the 3rd Corps artillery brigade in this image taken at Brandy Station, Virginia. Artist Alfred Waud of Harper's Weekly stands at right. At Cedar Mountain, Captain Robinson found himself temporarily under arrest by his brigade commander General Henry Prince; Prince himself would be captured during the battle by a private in the 23rd Virginia. Thus, wefought for two hours, aided by two batteries on our right and the 6thMaine on our left. Occupying the center of the artillery line as we did, wenecessarily received the most direct and fearful fire of the enemy. At onetime, in the short space of half an hour, one man was killed, three horsesshot, and both pieces in the right section struck, one of the pieces beingentirely disabled by a shot, which, striking its wrought iron axle three inchessquares, broke it near the wheel. [Ed. note- this was Lieutenant Haynes' section]

“Lieutenant Haynes section on the right seemed to get thebrunt of the fire and after getting about 50 rounds from each gun, a shellstruck the wheel of Sergeant Bangs’ piece and glancing struck Byron Phillips,tearing away part of his chin and shoulder. He was taken to the rear where hedied about two hours later. A little later, Sergeant Owen’s piece was struck bya shell and the axle broken so that it could not be used again. The splinters slightlywounded several of the gunners and the concussion of a shell as it struck andexploded very near Ambrose Vittum’s head caused a deafness in one ear fromwhich he has never recovered.” ~ History of the 4th Maine BatteryLight Artillery

At 5 o’clock,the infantry came to our rescue and amid incessant cheering, charged upon theenemy. The volleys of musketry, the booming of cannon, the cheers of the men,the clouds of smoke, and the whizzing of the shell through the air, with themingled groans of the wounded and dying, gave a tone of infernal horror to ascene which I hope never to witness again.

The battlelasted until nearly 8 o’clock. When we retired from the field, almostexhausted, the moon was shining brightly, lighting up this field of carnagewith unearthly splendor. As we passed through the woods again to encamp underarms for the night, we found that heavy reinforcements from Sigel and McDowellhad arrived and we felt comparatively safe. But it was not until the next day(the Sabbath) that we secured any peaceful rest. Then indeed it was refreshingto lie down upon the ground and easing our tired limbs, thank God for His kinddeliverance from the jaws of death.

This detail from the American Battlefield Trust's map of the Battle of Cedar Mountain shows the Federal artillery arrayed along the Mitchell's Station Road, the 4th Maine Battery being the battery just to the right of "Banks" on the map. According to Lieutenant Haynes, the 6th Maine Battery occupied the position to the 4th Maine's left.

This detail from the American Battlefield Trust's map of the Battle of Cedar Mountain shows the Federal artillery arrayed along the Mitchell's Station Road, the 4th Maine Battery being the battery just to the right of "Banks" on the map. According to Lieutenant Haynes, the 6th Maine Battery occupied the position to the 4th Maine's left. Our loss inkilled and wounded already amounts to about 1,000; it will not much, if any,exceed that amount. General Prince of Maine is taken prisoner but is unhurt. Inour battery we had one man killed and six slightly wounded. If our ranks hadbeen full, we must have lost many more. Ten of our horses were either killed ordisabled by solid shot or pieces of shell.

It is statedin some of the dailies that the 2nd and 5th MaineBatteries were in the fight and did great execution; this is a mistake. Theywere not on the field at all. The 5th Maine did not fire a singleround while the 2nd Maine fired a few rounds of ammunition after 9 o’clockupon a battery that contrived to annoy our advance until late at night. We donot detract from the honor of others but must claim our own. The 4thand 6th Maine were all the Maine batteries upon the field and theywere there, too, until they were ordered to leave. This was done in good orderwith the Rebel infantry within 30 rods of their rear sections.

The battleitself was a draw game. But the results flowing from it are replete withsuccess to our army. Jackson commenced a retreat the next day and is now beyondthe Rapidan with General Pope close on his heels. So much for the first fight;I will write again.

Lucius M.S. Haynes was a young pastor at the Baptist Church of Augusta, Maine when he joined the 4th Maine Battery in late 1861.

Sources:

Letter from First Lieutenant Lucius M.S. Haynes, 4thMaine Battery Light Artillery, Kennebec Journal (Maine), August 29, 1862, pg. 2

History of the 4th Maine Battery Light Artillery in the Civil War, 1861-1865. Augusta: Burleigh & Flynt, 1905

January 23, 2025

Hard Bread and Coffee Our Only Food, Blankets Our Only Shelter: The First March of the 20th Maine

In September 1862, the new recruits of the 20thMaine endured their first wartime march during the Maryland Campaign and “ahard one it was” remembered Sergeant Edward Simonton.

“We marched our march lastFriday and hard one it was, at the rate of 20 miles a day, under a scorchingsun, loaded down with gun, ammunition, rations and blankets- leaving ourknapsacks behind,” he wrote. “Hard bread and coffee was our only food-blanketsour only shelter at night. The old regiments said it was the hardest march theyever had. I felt ready to drop once or twice, but the idea that we were inpursuit of old Stonewall nerved me up to new effort and urged me onward.”

The 20thMaine, mustered into service on August 29, 1862, at Camp Mason, near Portland,Maine, had sailed from Boston to Alexandria, Virginia aboard the steamer Merrimackalong with the 36th Massachusetts. Upon arrival on September 6, theregiment camped at the Washington Arsenal, received weapons, and on the 11thwere assigned to General Daniel Butterfield’s brigade, Morrell’s Division, ofthe 5th Army Corps

Sergeant Simonton’sdescription of the 20th Maine’s first wartime march first sawpublication in the October 1, 1862, edition of the Bangor Daily Whig andCourier.

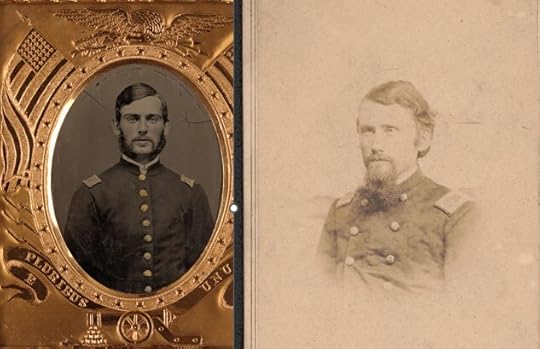

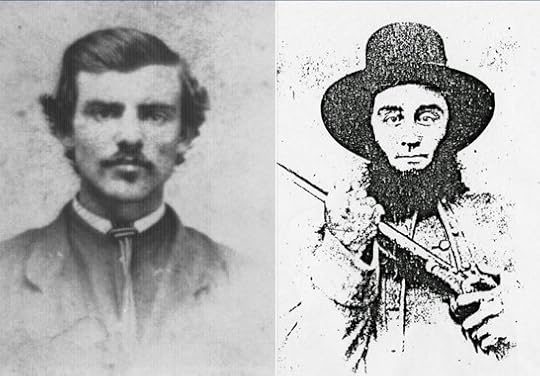

Sergeant Simonton's comrades during the first march of the 20th Maine included two men familiar to readers who have watched the movie Gettysburg: Sergeant Thomas Chamberlain, Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain's younger brother, at left was then in Co. I while Captain Ellis Spear on the right commanded Simonton's Co. G. Both men would be promoted to field grade by the end of the war: Spear became the colonel while Chamberlain became lieutenant colonel.

Sergeant Simonton's comrades during the first march of the 20th Maine included two men familiar to readers who have watched the movie Gettysburg: Sergeant Thomas Chamberlain, Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain's younger brother, at left was then in Co. I while Captain Ellis Spear on the right commanded Simonton's Co. G. Both men would be promoted to field grade by the end of the war: Spear became the colonel while Chamberlain became lieutenant colonel. Near Keedysville, Maryland

September 18, 1862

We leftWashington for Arlington Heights, about two miles into Virginia, a week agolast Monday. There our regiment was immediately attached to General Fitz JohnPorter’s corps (V), Morell’s Division, and General Dan Butterfield’s brigade.Ours is the only Maine regiment in the brigade; the others are New York andMichigan regiments.

Soon after wearrived at Arlington Heights, Porter’s corps was ordered to cross over intoMaryland to join McClellan in pursuit of Stonewall Jackson. We marched ourmarch last Friday [September 12] and hard one it was, at the rate of 20 miles aday, under a scorching sun, loaded down with gun, ammunition, rations andblankets- leaving our knapsacks behind. Hard bread and coffee was our only food-blanketsour only shelter at night. The old regiments said it was the hardest march theyever had. I felt ready to drop once or twice, but the idea that we were inpursuit of old Stonewall nerved me up to new effort and urged me onward. Many,however, fell out by the way.

We passedthrough the city of Frederick, a place I think about as large as Bangor. Herewe saw sad indications of Rebel raids- bridges destroyed, camps deserted, andgeneral ruin all around. Our march was through a beautiful region of thecountry. Day before yesterday we passed through Middletown, the scene of the latefight, and there saw many prisoners as well as arms, clothing, and heaps ofslain, scattered along the road, all proclaiming the horrors of war.

The Smith Farm near Keedysville was used as a hospital after the Battle of Antietam. This image was taken by Alexander Gardner soon after the battle.

The Smith Farm near Keedysville was used as a hospital after the Battle of Antietam. This image was taken by Alexander Gardner soon after the battle. Yesterday wearrived here near the village of Keedysville which is about five miles from thePotomac and nine from Harper’s Ferry. There was a terrific engagement all day,a constant roar of artillery-bang! Bang! A continuous rushing to and fro oftroops, artillery, cavalry, and infantry. Our corps acted as reserves, beingdrawn up in line of battle all day ready and expecting every moment to becalled into action. Shot and shell went whizzing over our heads and falling allaround us but doing no other injury to our division than to cause some of us tobend our necks and shrug our shoulders slightly. But towards night, our brigadehad orders to hasten to the right; we started on the double quick and expectedan engagement but had none for the enemy had appeared there in force and onseeing us, skedaddled.

We have atremendous force here and hope to be able to bag the entire Rebel force. Wouldto God that we might. Wouldn’t it be glorious? General McClellan is verypopular here. Just now he rode by our lines and was very heartily cheered as heis wherever he goes. He raised his cap and bowed his acknowledgements. He isundoubtedly the man; if let alone, he will, I believe, lead us on to finalvictory.

Sergeant Simonton would enjoy a long and activeservice during the Civil War, but only a small portion of it was spent with the20th Maine. After being commissioned as second lieutenant in January1863, he resigned scarcely two months later. However, in July 1863, he accepteda commission as second lieutenant in Co. I of the 1st U.S. ColoredTroops and would serve with that regiment until mustered out on September 29, 1865,as a captain. He was severely wounded in the left thigh on June 15, 1864,during the first battle of Petersburg and spent several months recuperatingfrom this wound. He received two brevet promotions, to major and lieutenantcolonel for “gallant conduct before Petersburg and for general good conduct andmeritorious service.” He would join the army a third time in February 1866,serving until September 1870 with the 4th U.S. Infantry.

Source:

Letter from Sergeant Edward D. Simonton, Co. G, 20thMaine Volunteer Infantry, Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Maine), October1, 1862, pg. 2

January 22, 2025

Life Among the ‘Wrecks’: The Convalescent Camp at Fort McHenry

As the thundering sounds of the battles of South Mountain andAntietam echoed in the dim distance, Lieutenant Henry Ayres of the 5thWisconsin Infantry, lying sick at a convalescent camp in Baltimore, called it “slowtorture. We felt like the leviathan of old that smelt the battle afar off andwished to be in it.”

"Convalescent Iam informed means a wreck- the leavings of a body that fever, diarrhea, wounds,and army surgeons have seen fit to let remain," he continued. "Some 800 non-commissionedofficers and privates with about 40 commissioned officers make up this camp. Themen are from all parts of the army and of every branch of the service; cavalry,artillery, and infantry all mixed up together. The convalescents went under thename and style of the “Cripple Brigade.”

LieutenantAyres’ description of life at the Fort Henry convalescent camp first appearedin the October 2, 1862, edition of the Berlin City Courant published inBerlin, Wisconsin.

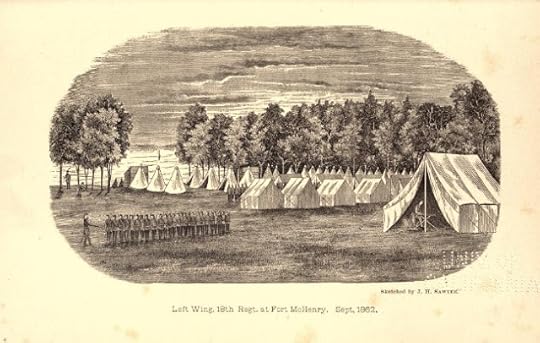

Lieutenant Ayres spent his mornings and afternoons teaching the men of Co. A, 18th Connecticut the nuances of drill at their camp within the enclosure at Fort McHenry. "The location of the camp was delightful," recalled Chaplain William C. Walker. "The duty was not heavy though constant and regular. Reveille and roll call at 5 a.m., breakfast at 6, guard mounting at 8, drill at 10, dinner call at 12, drill again at 3, dress parade at 5, supper at 6, tattoo at 9 and taps at 10 p.m." This depiction of that camp was included in the 18th Connecticut's regimental history penned by Chaplain Walker.

Lieutenant Ayres spent his mornings and afternoons teaching the men of Co. A, 18th Connecticut the nuances of drill at their camp within the enclosure at Fort McHenry. "The location of the camp was delightful," recalled Chaplain William C. Walker. "The duty was not heavy though constant and regular. Reveille and roll call at 5 a.m., breakfast at 6, guard mounting at 8, drill at 10, dinner call at 12, drill again at 3, dress parade at 5, supper at 6, tattoo at 9 and taps at 10 p.m." This depiction of that camp was included in the 18th Connecticut's regimental history penned by Chaplain Walker. Camp of Convalescents, Baltimore, Maryland

September 19, 1862

Have you heardof the Camp of Convalescents at Fort McHenry? Well, supposing you have, some ofyour readers have not and may like to hear all about it. It is a place or campwhere the good, kind, and very indulgent government at Washington places underMajor General John E. Wool all those enlisted men and commissioned officer whoare unable to return to their regiments directly from discharge from hospitalsin cities where they have been and recovered partially. Others come in daily totake a turn to quinine, the knife, and unwelcome air. Here they have to go intotents and have grounds to exercise upon not found in the cities with fresh,delightful sea breezes which come up the Chesapeake, the Patapsco, and Severn,for their especial benefit I suppose.

Convalescent Iam informed means a wreck- the leavings of a body that fever, diarrhea, wounds,and army surgeons have seen fit to let remain. Some 800 non-commissionedofficers and privates with about 40 commissioned officers make up this camp. Themen are from all parts of the army and of every branch of the service; cavalry,artillery, and infantry all mixed up together. There is a system, however, bywhich this camp is governed. Brevet Brigadier General Morris has command of thefort and all therein. The ranking convalescent is Major D.T. Everetts, 39thNew York Volunteers. General Morris put him in command of all the convalescedas we are sometimes called. The major divided up the 800 men into companieslettered from A-S, putting officers over them as in regular regiments. Theconvalescents, when this was done, went under the name and style of the “CrippleBrigade.”

The hospitaltents are large and supplied with good iron bedsteads. All the tents haveplatforms in them and mattresses or ticks filled with good clean straw. Thefood is good, what there is of it. I am sorry to say that complaints are madethat the rations are not full. Someone must be taking a spec somewhere…

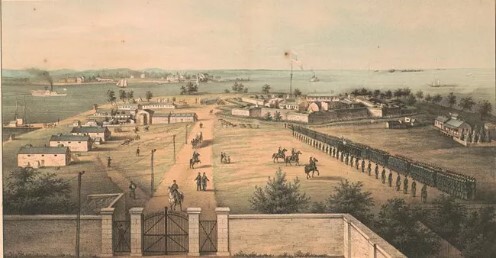

Fort McHenry's fame stems from it being the origin of our national anthem. By the time of the Civil War, Fort McHenry had been expanded considerably from its War of 1812 appearance and was armed with large caliber Columbiads for defense.

Fort McHenry's fame stems from it being the origin of our national anthem. By the time of the Civil War, Fort McHenry had been expanded considerably from its War of 1812 appearance and was armed with large caliber Columbiads for defense. Fort McHenryis situated on a peninsula that extends down to the bay between the PatapscoBasin and Severn River and about 1-1/2 miles from Baltimore. The point on whichthe Fort is erected is made ground. There has been a sort of earthwork on thispoint since the times of the Revolution, but this fort was built in 1831. In1814, the British shelled the earthworks and drove the soldiers out.

There could beno healthier spot selected than this for a camp. We can procure any delicacyour appetites may crave, Peaches, pears, plums, apples, melons, and every kindof fruit is daily brought into camp by the hucksters. The water is good and thebathing facilities are splendid.

Large squadsof men leave nearly every day for their regiments and large numbers come indaily from the different hospitals. About 30 are discharged daily and leave forhome. It would do you good to see the poor fellows faces brighten up when theyget their discharge. Fathers and wives come here from Pennsylvania, New Jersey,New York, the eastern states, and in fact all the states, seeking theirhusbands and sons to hasten their discharge.

The days dragslowly away. This convalescent camp is no place for an uneasy man. To be sick justenough to keep one from doing field duty, able to walk about one day, and abedthe next, is slow torture. Last Sunday, we heard the cannonading at Frederick,a distance of 40 miles, very plainly. We felt like the leviathan of old thatsmelt the battle afar off and wished to be in it.

Within theenclosure a wall runs across the peninsula. Some 50 rods above the fort areseveral buildings filled with secession sympathizers and political prisoners,nabbed by the police and lodged here for a cooling spell. We have some of Ashby’scavalry and spies, too. Within the fortress are a few dungeons, inside of whosewalls the biggest rascals are kept. These no one are allowed to see; their friendsoften come to see them, but in vain.

One artillerycompany of regulars is stationed within the fort and some of the volunteercompanies, also. Without the fort but within the enclosure the 18thConnecticut Volunteers are encamped, doing the guard duty principally. This isa new regiment and some eight officers of the convalescent brigade are regularlydetailed to teach them the drill. Your humble servant has Company A of thatNutmeg Battalion to instruct. It is a splendid regiment and commanded by a veryfine set of intelligent officers who need but little practice to make themadept in military drill.

I hope soon tobe leaving these quarters for those in the field. My health has greatlyimproved. The glorious news received today puts new enthusiasm in us all and wewish to leave drilling for the scene of action. The 5th Wisconsinhas been in again in its usual happy style, using up Howell Cobb’s brigadeagainst whom they had some scores. That brigade was doing picket duty on theYorktown defenses just opposite the 5th Wisconsin. Amasa Cobb tookHowell as the boys used to say he would, only give him a chance.

The weather isquite cool and agreeable. Little rain has fallen lately. The roads aresplendid. Today, minute guns were fired from the fort and flags flew at halfmast for General Reno. General Wool is at Harrisburg on business. The city ofBaltimore, one week ago on the eve of a riot, has subsided. Most of Porter’sgun fleet is laying off the city with the 13-inch mortars all sound on thegoose. There are only 6-8 men from our Wisconsin regiments in this camp.

Source:

Letter from Second Lieutenant Henry K.W. Ayres, Co. G, 5thWisconsin Volunteer Infantry, Berlin City Courant (Wisconsin), October2, 1862, pg. 2

January 20, 2025

Correcting a Slight Mistake: The 100th Illinois Saves the 8th Indiana Battery at Chickamauga

After losing a third of his command in the short span of 15 minutes on the first day of Chickamauga, Major Charles M. Hammond of the 100th Illinois was eager that the homefolks got the story right.

"I noticed in your issue of September 23rd a slight account of the fight of Saturday afternoon the 19th and in relation to Davis’s division rescuing the 8th Indiana Battery and discovered a slight mistake," he commented to the editors of the Wilmington Independent. After describing how the brigade arrived on the field, he wrote " At that moment, troops from Davis’s division came rushing through our lines and a battery from the same division, I think (though have not been able to ascertain positively) ran over us, killing one man and wounding several others. In the meantime, the Rebels were pouring in upon us a raking fire which was returned with interest. At this moment, General [Thomas J.] Wood rode up and ordered the 100th to charge, which was responded to with a shout and a rush, but our left being heavily pressed, began to give way, and the order was given to fall back and after retreating about 250 yards was again rallied and moved up to the crest of the knoll. We sent the enemy back kiting and recapturing that 8th Indiana Battery spoken of in yours of the 23rd, hauling it off by hand, the horses being mostly shot down. We drove the enemy back into the woods and held the ground fought over until darkness closed over the scene of action."

Major Hammond's account of Chickamauga first appeared in the October 28, 1863, edition of the Wilmington Independent published in Wilmington, Illinois.

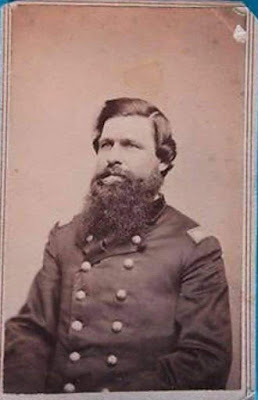

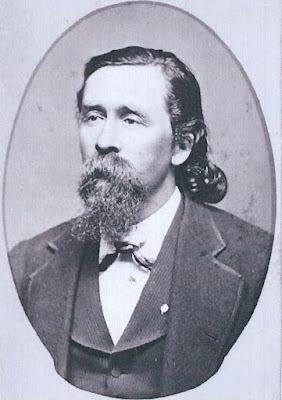

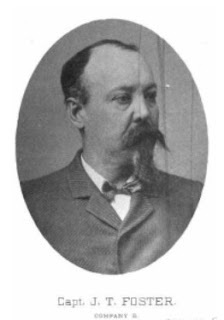

Major (later Colonel) Charles M. Hammond, 100th Illinois Volunteer Infantry

Major (later Colonel) Charles M. Hammond, 100th Illinois Volunteer InfantryCamp of 100th Regt. Illinois Vols., Chattanooga,Tennessee

October 8, 1863

Friend Steele,

I noticed inyour issue of September 23rd a slight account of the fight ofSaturday afternoon the 19th and in relation to Davis’s divisionrescuing the 8th Indiana Battery and discovered a slight mistake.There was the spot and that the time, full one-third of the 100thwas cut down in the short space of 15 minutes.

About 3 p.m.of that day, orders came to the First Brigade consisting of the 58thIndiana, 26th Ohio, 13th Michigan, 100thIllinois, and 8th Indiana Battery, then stationed at Gordon’s Mills,holding the ford to move on a double quick about two miles to our left to thesupport of Davis’s division who were then being heavily pressed. On arriving atthat point which was an open field skirted with timber on the right, left, andfront, we were immediately formed in two lines with the 26th Ohioand 100th Illinois in front, and the 58th Indiana and 13thMichigan in the rear supporting us while the 8th Indiana Battery tooka position between and a little in the rear of the 26th Ohio and 100thIllinois.

At that moment,troops from Davis’s division came rushing through our lines and a battery fromthe same division, I think (though have not been able to ascertain positively)ran over us, killing one man and wounding several others. In the meantime, theRebels were pouring in upon us a raking fire which was returned with interest.At this moment, General [Thomas J.] Wood rode up and ordered the 100thto charge, which was responded to with a shout and a rush, but our left beingheavily pressed, began to give way, and the order was given to fall back andafter retreating about 250 yards was again rallied and moved up to the crest ofthe knoll. We sent the enemy back kiting and recapturing that 8thIndiana Battery spoken of in yours of the 23rd, hauling it off byhand, the horses being mostly shot down. We drove the enemy back into the woodsand held the ground fought over until darkness closed over the scene of action.

Our regimentimmediately commenced looking over the field after our killed and wounded, butwere fired upon by the enemy, probably to afford them an opportunity forplundering. They succeeded, however, in bringing off most of the wounded, whowere conveyed in ambulances to the field hospital. Those are the facts, writtennot to boast of the 100th (for that is unnecessary) but to set thematter right before friends at home.

A Tennesseemajor with 48 deserters came into our lines yesterday morning. The major statesthat on the evening of the 4th, when they attacked and attempted tocarry our whole line by storm, the Tennessee troops did not come up to thework, which so enraged Longstreet’s troops that a pitched battle grew out of itwherein some 500-600 were killed and wounded. This is a Rebel account and Igive it for what is worth.

CaptainBradley opened on them today with a 32-lb Parrott, stirring them up on a hillestimated to be three miles from us. They returned the fire; but the shots fellamongst their own pickets, falling short nearly one mile which does not lookmuch like shelling Rosy out of Chattanooga.

Before Iclose, let me add a word for Chaplain Crews and Dr. Bowen who came to lookafter our wounded. On arriving at Stevenson and finding no conveyance to take themany farther, each immediately cut a good hickory and charged over themountains, a distance of 40 miles, on foot. On arriving at the camp of the 100th,notwithstanding they walked like old stage horses, they immediately repaired tothe hospital, took off their coats, rolled up their sleeves, and waded in,dressing the wounded, and sticking to their work while here like men mowing bythe acre. Long will they be remembered by the 100th and particularlyby those whose sufferings they relieved.

Trustingeverything is all quiet on the Potomac now that no fears are entertained froman attack by Longstreet and Washington is safe, I remain very respectfullyyours,

C.M. Hammond,

Major, 100th Ill. Vol.

To learn more about the actions of the First Brigade which fought under the command of Colonel George P. Buell at Chickamauga, please check out these posts:

In the Center at Chickamauga (58th Indiana)

The Chances of War: Captured Surgeons After Chickamauga (13th Michigan)

It is the Fate of War: The 26th Ohio at Chickamauga

Source:

Letter from Major Charles Morrel Hammond, 100thIllinois Volunteer Infantry, Wilmington Independent (Illinois), October28, 1863, pg. 2

January 18, 2025

The Rebels Flew Right and Left: A Hoosier at Mill Springs

Following the Federal victory at Mill Springs, PrivateWilliam Ruby of the 10th Indiana observed the mad scramble for souvenirsamongst his peers. He proudly reported securing one of the best prizes: aConfederate flag that belonged to a company in the 16th Alabama.

“We gave them such an ungodlyscare in the fight that they left their wagons, tents, trunks, horses, saddles,clothes, guns, pistols, ammunition of all kinds, cannons and in fact everythingimaginable,” he wrote to his father. “A person could not form the least idea ofthe scene which followed. There is hardly anyone but what had a relic or trophyto keep in remembrance of the ever-to-be remembered 19th of January.I captured a splendid banner belonging to the Marion County, Alabama Guards. Iwill present it to old Tippecanoe County, together with another one captured byJohnny Mackessey of our company. I also got a flute worth about $30, a silverwatch, a splendid pistol and case worth about $30. I have several nice littletrophies which I intend sending home at the first opportunity. Swords and longknives are in abundance.”

Private Ruby’s account of thefight at Mill Springs first saw publication in the January 25, 1862, edition ofthe Lafayette Journal & Courier published in Lafayette, Indiana.

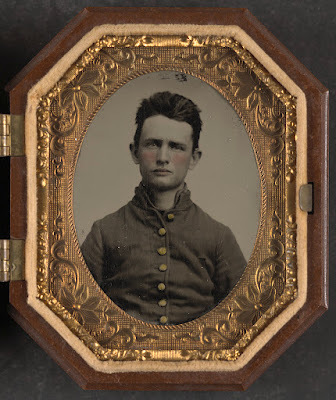

Corporal William Duncan fought at Mill Springs as part of Co. G of the 10th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. The Hoosier would not survive the war, dying June 25, 1864, from a wound sustained 10 days earlier during the Atlanta Campaign.

Corporal William Duncan fought at Mill Springs as part of Co. G of the 10th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. The Hoosier would not survive the war, dying June 25, 1864, from a wound sustained 10 days earlier during the Atlanta Campaign. Camp Beech Grove, inside Zolly’s Fortifications, Mill Spring,Kentucky

January 21, 1862

Dear father,

No doubt youare anxious to hear of my whereabouts. I can only say that I weathered thestorm and came out without a scratch. I shot two seceshers that I know of; I togetherswith others saw them fall. One was a color-bearer who waved his flag in ourfaces when I took good aim and down he went.

Last Sundaymorning, immediately after roll call, one of Woolford’s cavalry came into campwith the intelligence that a large force was advancing towards us. We had nosooner received the news than we heard the pickets firing briskly. The longroll was beat, the regiment formed in line of battle and started immediately tothe rescue of Co. K who were out on picket duty. We no sooner reached the sceneof action than Colonel Kise gave the command to “fire!” which the boys did witha will. Our situation was upon a small hill, the enemy on the hill just above us,but out of sight on account of the density of the underbrush. After a fight ofnear an hour, we were obliged to retreat, as the other regiments failed to comeup to sustain us.

We held ourground against a force of 9,000 strong. Before we retreated, they flanked usright and left so that we were in a crossfire, it was in this predicament thatwe lost most of our men. When we retired the 4th Kentucky came upand took our place, where they did good service. They fought valiantly as anytroops could have done. No sooner had we reached our camp than we were againcalled to rally, which we did with alacrity. No sooner had we formed in linethan General Thomas ordered us forward to sustain the 4th Kentucky,who were now nearly out of ammunition. We went forward to the front, squattedbehind a fence and pecked away at the Rebels whenever we got a chance.

In about half an hour, we wereordered to the woods where we again went on double quick. From this position,we were ordered to the left from there we were commanded to “charge bayonet”which we did with a yell and a good will. The Rebels flew right and left. Ourboys followed them, keeping up a continual fire. The Rebels fell all around;some of them were spunky, held their ground as though they intended stayingwith us a while, which in fact they did. After driving the Rebels out of thewoods, we kept after them through an open field when they squatted behind afence, when our boys, the 4th Kentucky, and 9th Ohiowhich had just come up, took to stumps and old dead trees.

The last half hour’s firing wasthe hottest and heaviest of all. During the engagement, our artillery firedsome 25-30 shells which made a general scatter among the seceshers. Theyreturned the fire with interest. In their flight the Rebels left two cannon andguns innumerable. After the Rebels fled, we followed them about half a milewhen we came to a halt, took breakfast at the expense of the party ‘cleaned out’which they had left behind them a short distance, intending (as they said) toreturn for it after they had given us what we needed and taken breakfast in ourcamp. Old General Zollicoffer said at starting that he would take breakfast inour camp or in hell that morning. I think he must certainly have taken hisbreakfast in the latter place as he was killed early in the engagement.

Colonel Speed Fry of the 4thKentucky claims the killing of Zollicoffer; others say that it was an Enfieldball that put out his lamp of life. One thing certain, Zollicoffer is dead.General George Crittenden was wounded and is a prisoner in our camp. We pursuedthe Rebels; they fled for their fortifications, but no officer could get themout of their bunks after they had once reached them in safety. The roads wepassed over were the worst and muddiest that I ever traveled or ever want to again.

National colors presented to the 10th Indiana by the Loyal Ladies of Lafayette; note the Mill Spring battle honor above the regimental identification.

National colors presented to the 10th Indiana by the Loyal Ladies of Lafayette; note the Mill Spring battle honor above the regimental identification. We came in sight of oldZollicoffer’s works just before dark and could see the Rebels at work inside oftheir entrenchments. They threw two shells at us but did us no damage. Ourartillerists threw about 40 rounds at them, which made them get up andskedaddle. All night we could see them crossing the river on their ferry boats.As soon as daylight set in, we threw eight or ten more shells at them as theycrossed the river. One shell set their boat on fire. After that we could seethe Rebels swimming the river. One whole regiment pitched in at once.

None of them got their gunsashore; they started in with them but lost them in the river. Over 3,000 gunswere lost in the Cumberland and over 100 horsemen drowned. On the night ofJanuary 19, our regiment lay out, Mother Earth for a bed, the bright canopy ofheaven above for a covering, and slept first rate, dreamed of home and seeingyou all. On the morning of the 20th, we took our frugal breakfastwhich consisted of a hard cracker and a piece of bacon, roasted on the coals.

About 10 o’clock, we formed inline and marched over to the camps lately vacated by the Confederates. Onceinside, we began to look around and were astonished to see how or what could possessa set of men to leave works as strong as they had here on the riverside. Theyhad natural fortifications and on the side from which we would have to attackthem were strong enough to hold with a small force against a host, we couldnever have taken them without a heavy loss on our side. And after we would havetaken their works on this side of the river, they could have held the otherside as they had heavy works all around them, whilst on the river side, theworks were almost impregnable.

They could have sunken everyboat that we could have got or attempted to use, but as luck would have it, we gavethem such an ungodly scare in the fight that they left their wagons, tents,trunks, horses, saddles, clothes, guns, pistols, ammunition of all kinds,cannons and in fact everything imaginable. A person could not form the leastidea of the scene which followed. There is hardly anyone but what had a relicor trophy to keep in remembrance of the ever-to-be remembered 19thof January.

Of our officers (that of Co. E)I can say this much: they behaved nobly, did their duty, none could have donebetter. Our loss in the 10th Indiana was 13 killed and 80 wounded,two of whom have since died. Our company lose one killed and six wounded.Lieutenant Louis Johnson has a slight scratch on the right arm. On our firstfight in the morning, we held our ground one hour and 40 minutes against 9,000men. Our force was only 700. One prisoner, a Mississippian whom I took, said tome, “By God, boys, you fight like hell. You are too heavy for us!” We had tocontend against Mississippians, South Carolinians, Alabamians, Louisianans,Tennesseans, and Kentuckians. The Hoosiers beat all and the 10thIndiana gets all the praise, the 4th Kentucky a share.

After the battle, General GeorgeThomas rode up before us. He told General Mahlon Manson that he never saw suchfighting in his life as we did and said, “three cheers for the brave Indianans.”Everyone says that we do beat hell in a fight. I captured a splendid bannerbelonging to the Marion County, Alabama Guards [Co. G or K, 16th Alabama].I will present it to old Tippecanoe County, together with another one capturedby Johnny Mackessey of our company. I also got a flute worth about $30, asilver watch, a splendid pistol and case worth about $30. I have several nicelittle trophies which I intend sending home at the first opportunity. Swordsand long knives are in abundance.

Mess No. 4 is quartered in a hutlately occupied by an Alabama captain. The Rebels had erected winter quartersand intended staying here. We captured over 1,600 head of horses and mules, 500wagons, and 14 cannons. Provisions are plenty- we have everything that we couldwish for and have had a good old time reading Secesh letters. The Rebels puttheir loss at over 2,000; we have picked up and buried over 250. We have about60 prisoners in our camp besides others; they say their loss is heavy.

To learn more about the Battle of Mill Springs, please check out these related posts:

Trembling in Our Very Boots: A Hoosier Describes Mill Springs (10th Indiana)

Nip and Tuck with the 2nd Minnesota at Mill Springs

A Librarian's First Battle: At Mill Springs with the 2nd Minnesota

A Tale of Two Colonels: A Blue & Gray View of Mill Springs (16th Alabama and 2nd Minnesota)

Failure at Fishing Creek: A Mississippi Tiger's Take on Mill Springs (15th Mississippi)

The Odyssey of Zollicoffer's Body

WilliamFranklin Ruby was born December 2, 1840, in Lafayette. Tippecanoe Co., Indianaat the age of 16, set out to make his fortune in Texas where he engaged in thedrug business for four years, but left the now now-seceded state on April 12, 1861.The overland journey took nearly three months to complete, Ruby arriving in Lafayetteon July 24, 1861.

Ruby enlisted as a private inCo. E of the 10th Indiana Volunteer Infantry on September 18, 1861.Promoted to regimental commissary sergeant on March 20, 1863, he mustered outwith the regiment September 19, 1864, at Indianapolis, Indiana. He had a veryactive service with the 10th Indiana, taking part in engagements atMill Spring, Perryville, Hoover’s Gap, Chickamauga, and throughout the Atlantacampaign. Cited for heroism is distributing cartridges to the regiment atPerryville, Ruby suffered a severe wound at Resaca in May 1864. “He was sent toGallatin, Tennessee with a train of supplies for the troops who had gone afterMorgan’s band at Muldraugh’s Hill and received a telegram to get back toElizabethtown as fast as possible as Morgan was making for the railroad at thatpoint to cut off and capture the train and supplies, but he won the race byabout 20 minutes and saved the train,” his obituary stated.

In April 1865 he wascommissioned as quartermaster of the 154th Indiana, one of Indiana’slast Civil War regiments, and served just a few months before mustering out ofservice for the final time August 4, 1865, at Winchester, Virginia. LieutenantRuby passed away October 13, 1924, in his hometown of Lafayette and is buriedat Greenbush Cemetery.

Source:

Letter from Private William Franklin Ruby, Co. E, 10thIndiana Volunteer Infantry, Lafayette Journal & Courier (Indiana), January25, 1862, pg. 3

January 16, 2025

The Bullet Magnet of Stones River: Dr. Yoder’s Wound Catalogue

At the Battle of Stones River, Lieutenant Noah Webster Yoder could lay sole claim tobeing the premier bullet magnet of the Army of the Cumberland. The Ohioan no doubt musthave felt snake bit at the battle as the 25-year-old formercountry doctor sustained no less than eight wounds in a manner ofminutes when his 51st Ohio vainly tried to stop Breckinridge’sattack on the afternoon of January 2, 1863.

LieutenantYoder’s story, copied from a family history of the Hostetler family, is givenas follows:

He educated himself, taughtschool, studied medicine and practiced till the war of 1861, when he enteredthe army as Lieutenant of Co. G, 51st Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Heengaged in many battles and skirmishes in Kentucky and Tennessee. At the battleof Stones River through some mistaken order of his superior officers hisregiment was ordered to advance over the brow of the hill and hold the positionat all hazards. The Rebels advanced in solid mass and cut the regiment all topieces.

"The Bullet Magnet of Stones River" First Lieutenant Noah Webster Yoder of Co. G, 51st Ohio Volunteer Infantry survived his eight wounds to return home and practice medicine in his home community of Shanesville, Ohio until perishing from a buggy accident in 1877.

"The Bullet Magnet of Stones River" First Lieutenant Noah Webster Yoder of Co. G, 51st Ohio Volunteer Infantry survived his eight wounds to return home and practice medicine in his home community of Shanesville, Ohio until perishing from a buggy accident in 1877. He was in command and refused toretreat against orders and was hit first by a large musket ball, which enteredin front of the breast, fractured the left collar bone and came out the backnear the spine. A branch of the large artery which leads from the heart to thehead was severed and the blood spurted at every pulsation. His knowledge ofsurgery taught him how to stop the blood, which saved his life.

His comrades, against his earnest protest,refused to abandon him on the field. In the midst of the hail of bullets andcannon balls they picked him up but were shot down one after another until atlast Mr. John Hall, of Berlin, Ohio, a powerful man who had been drafted andjoined the regiment only a few days before picked him up bodily and set himagainst a stump with his face toward the Rebels. While he was being carried in this manner a ball fractured his left leg belowthe knee.

The enemy charged past him andnothing but the stump against which he leaned kept him from being crushed todeath. A Rebel officer who was in the rear of the advancing charge wasattracted by his groans and upon looking at him was struck with the fineintellectual face. Noah had a remarkable, kind and striking appearance. Theofficer stooped down and spoke some kind words to him calling him"Pawdner". and inquired what he could do for him. The only reply thatNoah could make was, "Water! For God's sake give me some water!". Histhirst was caused by the loss of blood. No one that has not experienced thisfeeling can realize it. The officer slipped the strap of his canteen over hishead, went to the river, which was some distance away, brought it back and Noahwas no time in draining it dry. The officer said, "I must join my commandand can nothing more for you." Noah said, "Go! God Bless you."

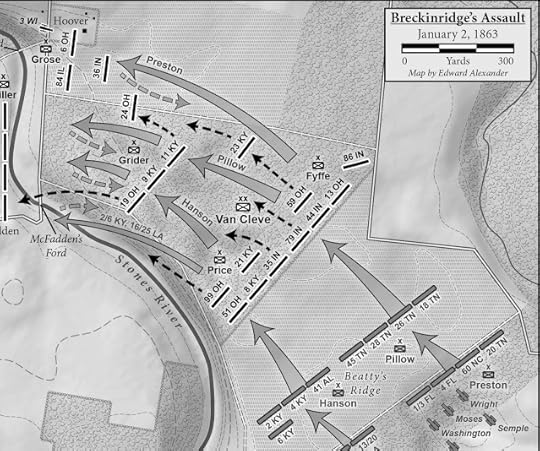

This map, from my recent book Hell by the Acre, shows the initial position of the 51st Ohio along Beatty's Ridge adjacent to McFadden's Ford at Stones River. Lieutenant Yoder sustained his wounds just to the rear of the regiment's first position as he tried to rally his company.

This map, from my recent book Hell by the Acre, shows the initial position of the 51st Ohio along Beatty's Ridge adjacent to McFadden's Ford at Stones River. Lieutenant Yoder sustained his wounds just to the rear of the regiment's first position as he tried to rally his company. The Rebels were soon driven backpast Noah and as fate would have it formed their lines of battle just beyondhim which left him about midway between the two firing lines and there for nineterrible hours he lay, the bullets and cannon balls from both sides passedover, round and by him. He was hit eight times. The end of his finger was cutoff, the breastbone was hit, a ball passed through his bowels and in fact hewas shot all to pieces.

This battle was fought January2, 1863, and yet Noah lived to raise a family of children and do much good inthe practice of medicine in the Shanesville community. He lived through allthis to be upset from his carriage, in what might be called a mud run, anddrowned while on his way to relieve a suffering patient. When his untimely andtragic death occurred, there was mourning in every household, mothers wentabout their work sobbing and children wept at the mention of his name. Wintersnows may fall and cover his grave, but his memory will ever remain green inthe hearts of those who knew him best. His heroism, patriotic devotion to hiscountry, and the great good he did to his people will be told from generationto generation.

After his wound, Dr. Yoder’sleft leg was amputated but he was promoted to regimental quartermaster April15, 1863, only to resign his post July 30, 1863. As stated above, he returnedhome to Shanesville, Ohio, surviving his eight wounds only to lose his life ina buggy accident March 9, 1877, at the age of 39.

Source:

Hostetler, Harvey. Descendants of Jacob Hostetler, theImmigrant of 1736. 1913, pgs. 699-700

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

January 14, 2025

A Blackened Page of History: The Aftermath of the Centralia Massacre

After gathering the bodies of his slain comrades,murdered at the hands of Bloody Bill Anderson and his band of guerillas outsidethe town of Centralia, Missouri in September 1864, one Iowa captain resolved toseek revenge for the deaths of his men.

“I arrived onthe ground the morning after the massacre and received a detailed account of itfrom an eyewitness,” he wrote to a friend in Illinois. “I had a small detail tolook after the murdered men of our own regiment, as it was known that seven ofthem had been on the train. I was not long in finding them, but in an awfullymangled condition. The butchers had thrown some of them across the track andcompelled the engineer to run a construction train over them. There were twomen from my own company among the slain and I found one of them with ninebullet holes in him and his throat cut. The other one had three bullets and histhroat cut. Now talk of peace with such a race, will you? I have made a vow tobe revenged for the murder of my two boys, and I will have it with a big premiumbefore I leave this state if the authorities don’t watch me too closely…”

The letter waspublished unsigned, but I strongly suspect was written by Captain Thomas Jonesof Co. C of the 1st Iowa Cavalry. It first saw publication in theOctober 19, 1864, edition of the Wilmington Independent published in Wilmington, Illinois.

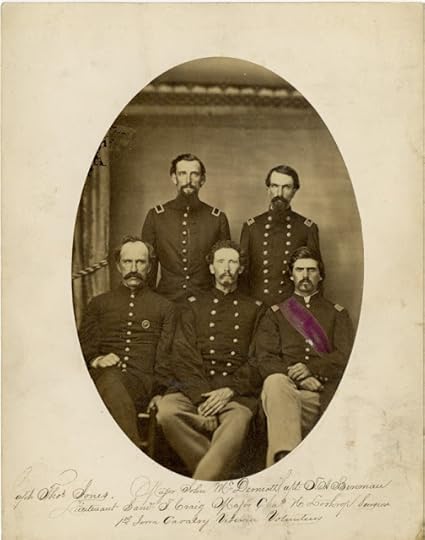

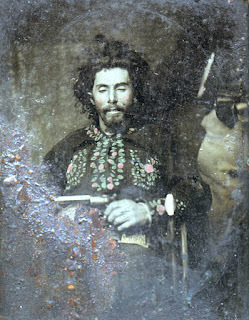

This photo of five officers of the 1st Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, depicts the soldier that I believe wrote this description of the Centralia Massacre, Captain Thomas Jones of Co. C who sits at bottom left. The officers, all identified, are as follows: Jones, bottom row left, Major John McDermott at center, Captain T.A. Bereman at right. Top row left is Lieutenant Samuel T. Craig and at right, Major Charles Lothrop. (Wilson's Creek National Battlefield)

This photo of five officers of the 1st Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, depicts the soldier that I believe wrote this description of the Centralia Massacre, Captain Thomas Jones of Co. C who sits at bottom left. The officers, all identified, are as follows: Jones, bottom row left, Major John McDermott at center, Captain T.A. Bereman at right. Top row left is Lieutenant Samuel T. Craig and at right, Major Charles Lothrop. (Wilson's Creek National Battlefield) Mexico, Missouri

October 2, 1864

On the 27thof September, as the train going west from St. Louis to Macon City was passing Centralia,13 miles west of this place, it was stopped by a band of men claiming to beConfederate soldiers, but dressed in Federal uniform, and robbed of all thevaluables and money upon the passengers and express. They compelled thepassengers to get off the train which they set fire to and started off withoutengineer or conductor.

There were alarge number of discharged soldiers on their way to see their loved ones athome after having served out their time, but alas, that home they were destinednever to see. After collecting all the booty they could find, they proceeded totheir more hellish and brutal acts. They marched out all who wore any portionof the Federal uniform and shot them down like dogs, mangling and mutilatingthem in the most horrible manner.

I arrived onthe ground the morning after the massacre and received a detailed account of itfrom an eyewitness. I had a small detail to look after the murdered men of ourown regiment, as it was known that seven of them had been on the train. I wasnot long in finding them, but in an awfully mangled condition. The butchers hadthrown some of them across the track and compelled the engineer to run aconstruction train over them. There were two men from my own company among theslain and I found one of them with nine bullet holes in him and his throat cut.The other one had three bullets and his throat cut. These were men who had gonethrough many dangers and always did their duty bravely.

We brought thepoor fellows to this place and gave them a decent burial. We picked up 27 othersand brought them here; this was all we could transport. There 155 others whomwe buried near where they fell. Two others had crawled away some distance anddied, making a total of 157 souls.

Now talk ofpeace with such a race, will you? I have made a vow to be revenged for themurder of my two boys, and I will have it with a big premium before I leavethis state if the authorities don’t watch me too closely as I am set for themand am not compelled to make report of all that transpires while out scouting.

The CentraliaMassacre was actually a two-part affair; the first event, described above, occurredon the morning of September 27, 1864, and resulted in a total of 22 soldiersand a single civilian being murdered. Later that afternoon, a detachment oftroops from the 39th Missouri Militia under Major Andrew V.E. Johnstonarrived and attacked Anderson’s camp. The militia were slaughtered nearly tothe man and their bodies left all about town- this became known as the Battle of Centralia.

General Clinton B. Fisk messagedhis commanding officer General William S. Rosecrans a few days later that Major Johnston's command was “completely overwhelmed and himself and command subjected to the mostinhuman butchery and barbarities that blacken the pages of history. MajorJohnston was murdered and scalped, 130 of his officers and men shared his fate.Most of them were shot through the head, then scalped, bayonets thrust throughthem, ears and noses cut off, and privates torn off and thrust into the mouthsof the dying. The heart sickens and the mind recoils at the recital andcontemplation of the barbarous atrocities.”

It took a fairamount of detective work to land on the probable author of this letter asCaptain Thomas Jones of Co. C of the 1st Iowa Cavalry. This letter,unsigned, was described as being from “a captain in an Iowa cavalry regimentwriting to his friend in this town,” that town being Wilmington, Illinois.

The first task became narrowingdown which Iowa cavalry regiment might have had troops either mustering out or activein Missouri in late September 1864. A quick search of the regimental servicesof Iowa’s cavalry regiments narrowed it down to the 1st and 3rdregiments. A deeper read of the History of Boone County’s account of theCentralia Massacre makes mention of a soldier of the 1st Iowa Cavalrycalling out the guerillas while still on board the train.

LurtonIngersoll’s compendium of histories of Iowa regiments during the Civil War sealedthe deal. In his account of the services of the 1st Iowa Cavalry, hestates that “on the 27th of September, the savage guerilla BillAnderson attacked and captured a train near Centralia and atrociously murderedall the soldiers aboard, numbering about 30, of whom seven were members of the1st Iowa Cavalry.” Seven men matched exactly what our correspondentstated was his regiment’s loss in that bloody affair. So, it is the 1stIowa Cavalry.

Ingersoll then gave the names ofthe seven men of the 1st Iowa Cavalry who were murdered, which are as follows:

Private Owen P. Gore, Co. A

Private Oscar G. Williams, Co. B

Private George W. Dilley, Co. B

Private John Russell, Co. C

Private Charles E. Madera, Co. C

Corporal Joseph H. Arnold, Co. E

Private Charles G. Carpenter, Co. K

You mightrecall that our correspondent specifically mentioned finding two members of hiscompany, which narrowed it down to the captain of either Co. B or Co. C of the1st Iowa Cavalry. A quick search of the rosters of both companiesyielded a pair of candidates:

Captain Joseph T. Foster, of Co. B. Fosterenlisted from Lyons, Iowa as the 21-year-old Fourth Sergeant of Co. B on May 1,1861, and progressively moved up the ranks, first to battalion sergeant majoron October 7, 1861, orderly sergeant of Co. B on September 1, 1862, first lieutenanton December 21, 1862, and captain of August 5, 1864. He was wounded July 11,1862, during the engagement at Big Creek Bluffs, Missouri. After being musteredout of service with the 1st Iowa on February 15, 1866, he accepted acommission as first lieutenant in the 8th U.S. Cavalry and servedwith the regulars until he was dismissed December 28, 1868.

Captain Thomas Jones of Co. C. Jonesenlisted from Towanda, Illinois as a 31-year-old private in Co. C on June 13,1861. Jones became orderly sergeant of the company on October 7, 1861, and wassuccessively promoted to second lieutenant on July 1, 1862, first lieutenant onDecember 12, 1862, and finally to captain on February 14, 1863. Jones wasdischarged on December 16, 1864, at St. Louis, Missouri.

The fact thatJones was a resident of Towanda, Illinois, a town along the railroad betweenChicago and Wilmington, leads me to believe that the most probable author ofthe letter was Jones and not Foster, but I can’t say that with absolute certainty.What I can say with certainty is that the letter, a grisly account of theaftermath of the Centralia Massacre, was written by one of these two officersof the 1st Iowa Cavalry.

Bill Anderson photographed a month after the Centralia Massacre, killed in a skirmish with Federal troops.

Bill Anderson photographed a month after the Centralia Massacre, killed in a skirmish with Federal troops. It is worthnoting that Bloody Bill Anderson’s days of terror were numbered, and his endreflects the epitome of savagery that gripped the Missouri frontier in the waningdays of the Civil War. Scarcely a month at the events at Centralia, Andersonwas shot behind the ear and instantly killed while charging against a Federaldetachment near Albany, Missouri. His body was taken to nearby Richmond,Missouri, photographed, and paraded around town; one soldier cut off his fingerto steal a ring. A pair of brothers, Frank and Jesse James, who rode with Anderson, went on to notorious careers as desperadoes in the Wild West of the post-CivilWar era.

Source:

Letter from Captain Thomas Jones, Co. C, 1st IowaVolunteer Cavalry, Wilmington Independent (Illinois), October 19, 1864,pg. 2

January 13, 2025

Sad Freight of Mangled Humanity: Arrival of the Wounded of Shiloh at Louisville

On Sunday night, April 13, 1862, Lieutenant Benjamin H. Oberof the 77th Pennsylvania witnessed one of the saddest sights of hisshort military career: the arrival of the steamboat Minnehaha at Louisville,Kentucky carrying a boatload of wounded soldiers from the Shiloh battlefield.He climbed aboard eagerly seeking news of his comrades.

“I walkedthrough the cabins and looked into every suffering face, fearing at every stepto meet the gaze of a wounded comrade with whom I had been so long associatedand with whom I enjoyed so many pleasures and endured so many hardships,” hewrote. “But there were no familiar faces there. It is impossible to describethe sufferings of many of the poor fellows. Some of them were writhing andtwisting, rolling over on their hard couches and uttering piteous groans thatmade the heart ache. Others less severely wounded seemed cheerful and happy andvery ready to communicate all they knew about the battle, which they said wasvery little as after the first attack it was every man for “number one.”

LieutenantOber, a former employee of the Lancaster Daily Evening Express and frequent correspondent, was absent sick from his regiment during the battle, and would soon resign hiscommission scarcely a week later. His letter first appeared in the April 18,1862, edition of the Lancaster Daily Evening Express. I’ve supplementedhis account with articles from the Louisville Daily Journal which alsonot only document the arrival of the Minnehaha, but provide a completelist of names of the wounded who were aboard and what hospital they wereassigned to after arrival.

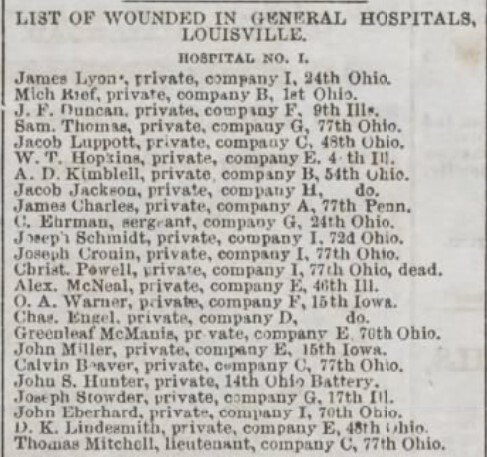

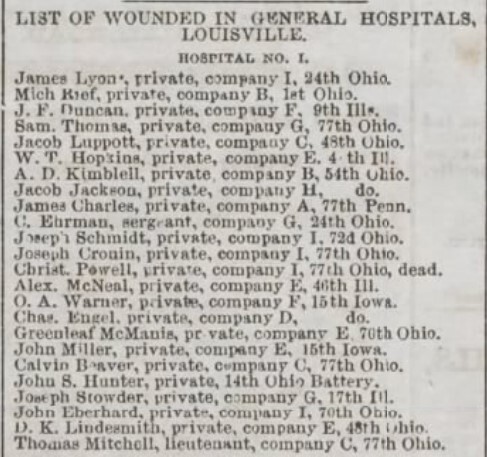

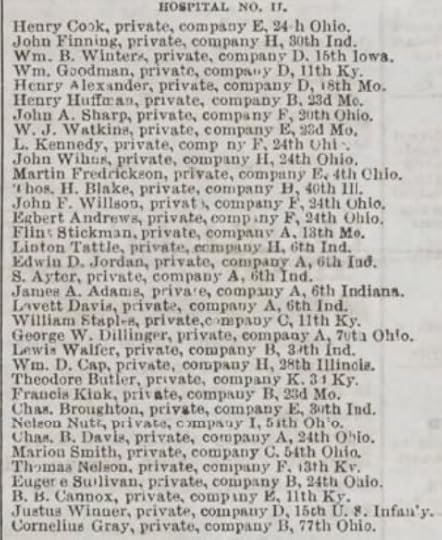

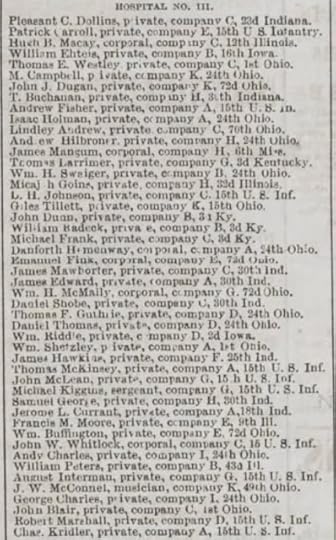

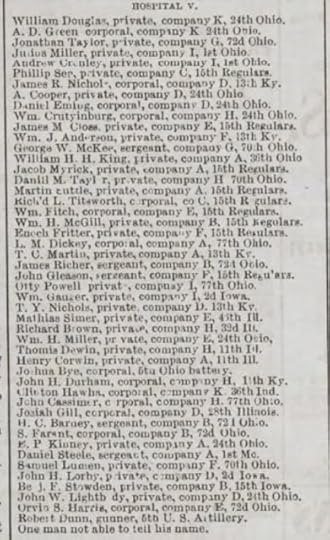

These men, delivered to Hospital No. 1 in Louisville, were among the wounded soldiers of both armies who were aboard the Minnehaha. The remainder of the lists of wounded soldiers, pulled from the Louisville Daily Journal, are at the bottom of the article.

These men, delivered to Hospital No. 1 in Louisville, were among the wounded soldiers of both armies who were aboard the Minnehaha. The remainder of the lists of wounded soldiers, pulled from the Louisville Daily Journal, are at the bottom of the article.Louisville, Kentucky

April 13, 1862

We aregradually getting the facts of the great battle at Pittsburg Landing. The firstaccounts seem, for once, to have been mainly correct with the exception of thenumber of killed and wounded. The first day, everything favored the Confederatesand they were masters of the field. The next, however, we regained our groundand advanced our troops some ten miles further than our first position and sentthe Rebels in full retreat, though in excellent order, in the direction ofCorinth. These are the leading facts and indeed about all the information Icould obtain after questioning and conversing with some 20 wounded officers andmen who were in the thickest of the fight and who arrived in this city duringtoday and this evening.

I was the witnessof a scene this evening which I hope never to look upon again, and, which painfullyillustrates the horrible character of this fratricidal strife. I saw 200wounded soldiers, 60 of whom were Rebels and prisoners, stretched upon the cabinfloor of a steamboat, mutilated and mangled in every conceivable form and manyof them groaning and apparently suffering the most intense agony.

It wasyesterday announced in one of the city papers that several boatloads of thewounded would arrive in the city. The announcement had the effect of attractinghundreds of people to the neighborhood of the levee where the boats wereexpected to stop at an early hour in the morning. As the day wore on, thethrong increased and it finally became so large that it became necessary forthe Provost Marshal to order out several companies of soldiers in order toclear the street. This was accomplished and the crowd was not allowed toapproach within a block of the levee. But still the crowd remained, many ofwhom were women and children, weeping and looking anxiously down the river,hoping the expected boats would bring some tidings of absent friends.

But the daywas passing away and still no signs of the anxiously looked for boats untilnear evening when far down the river, the black smoke of an approaching steamerput everybody on the lookout. The boat finally neared the landed and proved tobe the Minnehaha with 200 wounded as already stated. A half hour beforethe arrival of the boat, I was standing in front of the crowd when the officercommanding the guard noticed me and sent his orderly to invite me within thelines. I very readily accepted the invitation. I was in company with Mr. JamesStewart of your city [Lancaster, Pa.] who has a nephew in the 31stIndiana which was so terribly cut up on the first day of the fight. He was veryanxious to obtain some information concerning the nephew.

As the boatapproached the levee, the neighboring house tops, sheds, and all availableplaces, became crowded with people with the river was alive with skiffs filledwith anxious friends or by those prompted by morbid curiosity. Knowing thatGeneral McCook’s division was in the fight the second day and as my regiment(the 77th Pennsylvania) is in that division, I was very eager tolearn whether it was in the engagement. I made inquiry of several officers andsoldiers who gave their opinion that it was and a private of an Indianaregiment [probably the 29th or 30th Indiana who were inthe same brigade as the 77th- Ed. note] and he assured me that hewas acquainted with the regiment and was sure it was in the fight, but couldnot tell whether there was any wounded on board belonging to it.

“The steamer Minnehaha reached here at a late hourlast night with 240 wounded soldiers from the field at Pittsburg. They wereindiscriminately selected from friends and foes and it is not yet known howmany Rebels were among them. As yet, no list has been made out for the surgeonsand all others who have them in charge are entirely exhausted and werecompelled to seek repose. The wounded were all removed from the boat to thevarious hospitals.” ~Louisville Daily Journal, April 14, 1862, pg. 3

I thereforewalked through the cabins and looked into every suffering face, fearing atevery step to meet the gaze of a wounded comrade with whom I had been so longassociated and with whom I enjoyed so many pleasures and endured so manyhardships. But there were no familiar faces there. The wounded were mostly ofKentucky and Indiana regiments, but there will be several boats in tonight andI was informed that the next will contain the wounded of General McCook’sdivision. If so, tomorrow morning I will have to undergo the painful ordealover again.

It isimpossible to describe the sufferings of many of the poor fellows. Some of themwere writhing and twisting, rolling over on their hard couches and uttering piteousgroans that made the heart ache. Others less severely wounded seemed cheerfuland happy and very ready to communicate all they knew about the battle, whichthey said was very little as after the first attack it was every man for “numberone.”

On April 15,1862, the Louisville Daily Journal published a full list of the “sadfreight of mangled humanity brought to the hospitals of this city on thesteamer Minnehaha on Sunday night. Since their arrival, the followinghave died: Charles Powell, Co. I, 77th Ohio; John Fletcher, Co. H,36th Indiana; Hardin Boyd, Co. C, 4th Kentucky."

Below are thesnapshots for each hospital:

Private William McEnally (left) and Emanuel Fink (right) of the 72nd Ohio were among the wounded soldiers delivered to Louisville by the Minnehaha. Both went to Hospital No. 3- McEnally would survive his wound and return to the regiment; Fink would not.

Private William McEnally (left) and Emanuel Fink (right) of the 72nd Ohio were among the wounded soldiers delivered to Louisville by the Minnehaha. Both went to Hospital No. 3- McEnally would survive his wound and return to the regiment; Fink would not.

Sources:

Letter from First Lieutenant Benjamin H. Ober, Co. K, 77thPennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Lancaster Daily Evening Express(Pennsylvania), April 18, 1862, pg. 1

“The steamer Minnehaha,” Louisville Daily Journal(Kentucky), April 14, 1862, pg. 3

“The Pittsburg Wounded,” Louisville Daily Journal(Kentucky), April 15, 1862, pg. 3

January 11, 2025

With the Chicago Mercantile Battery at Arkansas Post

Surveying the carnage wrought by his battery during thereduction of Fort Hindman, Arkansas in January 1863, Private Everett Hudson ofthe Chicago Mercantile Battery came away with a harsh education in the horrorsof war.

“Such a sightas met my eyes when I first gained the top of the pits I can never forget,” hewrote a week later. “Here and there lay dead and wounded Rebels in allconceivable forms. Some lay with a head off, some a leg, others an arm, andsome mangled all to pieces. Inside the casements, our shells had burst and hitthe gunners on the head and spattered the brains all over the walls. Pieces ofshells weighing 15-20 lbs. were found imbedded in the solid walls inside,showing that our shells were terribly destructive.”

The carnagewas not one-sided. Hudson witnessed a Confederate shell that detonated among anearby group of Federal soldiers. “The ball cut men in two, just below theheart. I was standing only a few yards distant at the time and only a fewmoments before was standing with the same group,” he recalled.

Hudson, agrocery clerk working in Chicago at the time of his enlistment, joined theChicago Mercantile Battery under the command of Captain Charles G. Cooley onAugust 20, 1862. The battery was organized under the auspices of the MercantileAssociation, consisting of the most prominent merchants in the city of Chicago.The battery was initially equipped with four 6-lb smoothbores and two 3-inch wrought-ironordnance rifles and Private Hudson found himself assigned to one of thesmoothbore pieces.

He would serve through the restof the war with the battery, mustering out July 10, 1865, at Chicago. In thosethree years, the battery would see extensive action in the western theater,fighting mostly as part of the 13th Army Corps in the Army of theTennessee. The engagements at Chickasaw Bayou, Port Gibson, Champion’s Hill, Vicksburg,and Sabine Crossroads thundered with the sound of the Mercantile battery’s sixguns.

Hudson would survive the war. Anative of Ohio, he had moved to Illinois with his parents in 1846 and had hisfirst clerkship in a general store in Wilmington, Illinois, which explains whyhis letter appeared in the local newspaper. Not long after his discharge,Hudson journeyed west to Dakota Territory and settled in what later becameYankton, South Dakota. His mercantile training served him well, as Hudson becameinvolved in banking, real estate, insurance, and brokerage firms during hislengthy business career. In 1874, he married Clara E. Warren with whom heenjoyed 22 years of marriage until her death in 1896. Hudson never remarried, devotinghis time to Yankton College, the local school board, and his associations withthe Grand Army of the Republic until his death at age 85 on October 28, 1924,in Windom, Minnesota.

Private Hudson’s account ofArkansas Post appeared on the first page of the February 18, 1863, edition ofthe Wilmington Independent published in Wilmington, Illinois.

The red stripes of this Cincinnati-depot shell jacket denote the artillery branch; Private Hudson and his comrades of the Chicago Mercantile Battery wore similar jackets when they took part in the operations against Fort Hindman in early 1863.

The red stripes of this Cincinnati-depot shell jacket denote the artillery branch; Private Hudson and his comrades of the Chicago Mercantile Battery wore similar jackets when they took part in the operations against Fort Hindman in early 1863. On board steamer Warsaw

January 18, 1863

The last timeI wrote you, I was on board the steamer Adriatic bound up the Mississippi Riverand destination not positively known. You have undoubtedly heard ere this wherewe went and what we have been about and now anxiously await a letter from me.

Theparticulars of the capture of Fort Hindman (named after the illustrious senatorfrom Arkansas when the Secesh seceded from the halls of Congress) are about asfollows. We arrived before the fort about dusk on Saturday the 10thinstant, and the artillery, cavalry, and infantry were immediately ordered todebark and form in line of battle around the entire fort and rifle pits, thisline being about two miles long. The enclosure formed by the rifle pitscontained, I should judge, about 200 acres. The fort was on the extreme leftand lower corner of the area. The works were built on a bend of the river, thebend being convex from the land; the rifle pits extended from the river at thefort out into the woods and around to the river above. Distance was half a milefrom the starting point by water and as I said before, two miles around by thepits.

The fort wasso arranged that if we gained possession of the ground inside the pits that westill had the fort to take as there was an embankment thrown up between thefort and area of the main ground. Upon this embankment were heavy gunscommanding any point of the compass. On the side of the fort commanding theriver were two blockhouses built of heavy green oak timber hewn a foot squareand laid up double, making it old solid mass of timber two feet thick and theroof being built in the same manner as the walls excepting the roof is casedover with iron half an inch thick. The roof being a one-sided roof withquarter-pitch slanting from the river.

Inside thecasements were one 84-lb and one 120-lb Parrott guns. Mark me, one gun throwinga ball 84 lbs. and the other 120 lbs., each capable of throwing accurately twomiles. In other parts of the fort were guns and howitzers throwing balls from6-32 lbs., being flying artillery in all parts of the field. There were insidethe enclosure about 60 baggage wagons, 400 mules and horses, and quite a largesupply of commissary stores in sufficient quantities to last the garrison of8,000 men about three months. Everything in and about the fort was done asthough they thought it impregnable and therefore intended to make it apermanent post. Inside the fort was a well about 120 feet deep with an abundantsupply of water. In this well hung a fireman’s hose with one end attached tothe engine and the other end in the water; this was designed to put out fire incase we threw hot shot.

Well, to goback to the time we arrived. The order was executed in quick time and the firstintimation of our presence the Rebs had was when they were completelysurrounded by 10,000 men. All was now ready, a rocket was sent up as a signalto the gunboats when they (three in number) opened the ball with a terrificbombardment against the fort while we, the artillery and infantry, lay low inthe bushes watching the effect of our balls. This was after dark, but the firefrom the gunboats and the fires about the fort afforded us light enough to seepretty well.

The gunboats steamed up so closeto the fort that the Rebels’ guns could not hit ours. The fort was on a highhill and the heavy guns were so fixed that they could not shoot low enoughinside of a half mile to hit us. I suppose the Rebs did not think the Yankeeswere so audacious as to steam up as close as we did. The only chance they hadof hitting the gunboats was from the time they were two miles distant untilthey were within half a mile; after that, we were under their range.

Their guns, weighing severaltons, could not be moved without some great mechanical force that could not begot in readiness while so hotly engaged as they were. The bombardment wascontinued without intermission for an hour and 20 minutes. All this time, theground jarred worse than any thunder I ever heard. There was a constant quiver likelightning in the air high over the flat from the cannon’s mouth. How to accountfor this singular phenomenon was the query of all observers. I suppose thoughit was caused by the hot and cold air coming into contact, similar to the caseof lightning. After the bombardment had ceased, all was still and calm as agraveyard until the first rays of light on the morning of the 11thwhen we ordered the Rebels to surrender, which they politely declined. The Rebswere under the command of that unmerciful old Churchill, who you will recollecthad command of the Indians at the Battle of Pea Ridge and who ordered them, orlet them, bayonet our wounded upon the field.

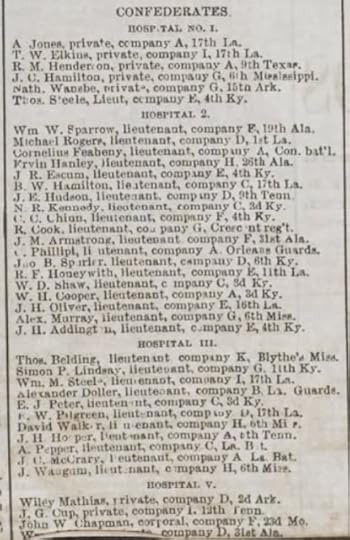

Union gunboats firing upon Fort Hindman on January 11, 1863.

Union gunboats firing upon Fort Hindman on January 11, 1863. After the preliminaries werepassed through, the ball again opened at half past 12- musketry, artillery, andgunboats combined. For 300 yards from the rifle pits all the way round stoodtrees from the size of a man’s body up to two and even three feet in diameter.These had been fell by the Rebs in order to have an open field in which tofight when they were assailed. But here fortune favored us, for they had eitherdelayed or had not time to remove them before our appearance, probably thelatter as the trees looked fresh cut. These trees afforded us great shelter.

The infantry entered thisunderbrush and poured volley after volley into the Rebel ranks every time theyraised their heads above the pits to fire. The artillery would aim about 6 inchesbelow the top of the pit and then could be seen sand, sticks, and splintersflying high into the air. The gunboats, in the meantime, were throwing grapeand shell over the fort to the opposite side of the field, doing terrible execution.Their shells would strike trees as large as my body and cut them straight intwo. There was one large tree in the center of the enclosure, a perfect oldmonarch, with many branches as large as a good-sized tree; these branches wereall riddled by our shell and solid shot.

The battle went on in this wayfor just four hours when they hoisted the white flag and surrenderedunconditionally 8,000 men, 10,00 stand of arms, a large quantity of ammunition,and other ordnance stores besides about half the horses and miles. The otherhalf lay dead or wounded upon the field. When they capitulated, we marched upto their works and took immediate possession of everything.

But such a sight as met my eyeswhen I first gained the top of the pits I can never forget! Here and there laydead and wounded Rebels in all conceivable forms. Some lay with a head off,some a leg, others an arm, and some mangled all to pieces. Inside thecasements, our shells had burst and hit the gunners on the head and spatteredthe brains all over the walls. Pieces of shells weighing 15-20 lbs. were foundimbedded in the solid walls inside, showing that our shells were terriblydestructive. The very gun I was working upon was sighted upon a 20-lb howitzerwith solid shot and fired and was seen to break right into the center or aboutthe trunnions. There were about a dozen guns served in like manner.

The fallen trees were so great aprotection that our loss was comparatively small in proportion to the Rebels.Our battery came out without any killed and only three wounded, two of themslightly. Our loss would have been severe if the Rebs had not been so hotlyengaged by the infantry from the center. It could not have been otherwise as wewere only 300 yards from the Rebel sharpshooters. Some of our horses were shot.

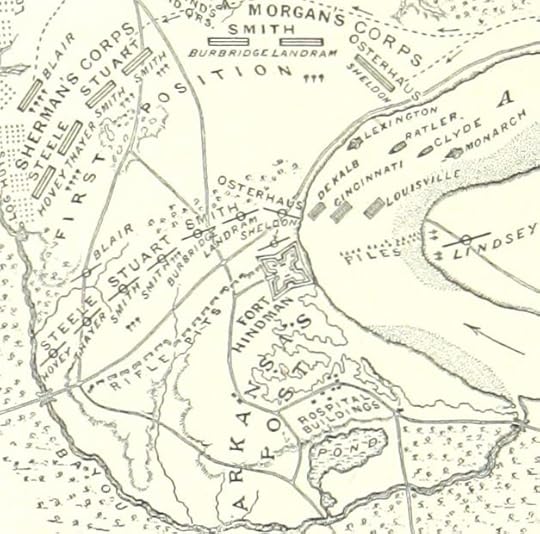

The Chicago Mercantile Battery was attached General Andrew J. Smith's division which constituted the federal left center during the operations against Fort Hindman. Hudson relates an incident in which his battery overshot a Confederate battery and dropped a shell amongst the hospital buildings shown on the map above as being located behind the fort proper.