Daniel A. Masters's Blog, page 2

August 31, 2025

An Echo Like the Wail of Departed Spirits: With the 16th Michigan at Gaines Mill

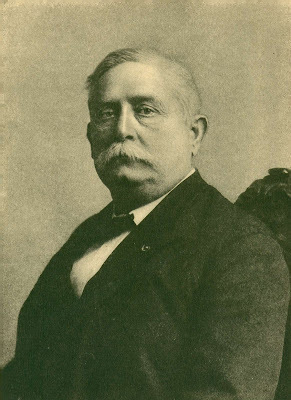

As he watchedthe remnants of the Army of the Potomac fall back after being defeated at theBattle of Gaines Mill on June 27, 1862, the confidence of Hospital StewardWilliam L. Berry of the 16th Michigan in the generalship of GeorgeMcClellan suffered its first blow.

“The thought came to my mind: what did all this mean? WasMcClellan surprised and was the vast army that the government had been socarefully nursing for the past year suddenly to be put to rout and driven back?Was all the admirable plans to be defeated and was the enemy to still holdtheir sway? I pondered over it all night and could come to no reasonable conclusionwhy we should be so defeated and driven from the ground that we had held for solong a time. I’ll confess that for the first time, my confidence in McClellanwas shaken but felt satisfied that all would turn out for the best,” theCanadian wrote home.

Hospital Steward Berry’s account of Gaines Mill first sawpublication in the July 25, 1862, edition of the Ingersoll Chronicle,published in Ingersoll, Ontario, Canada, his hometown. Later in the war, Berry wascommissioned as an assistant surgeon and wrote regularly to the Chronicle detailingthe services of the 16th Michigan.

During the Seven Days’ campaign, the16th Michigan was part of Colonel Dan Butterfield’s Third Brigade ofGeneral George Morrell’s First Division of the 5th Army Corps, underGeneral Fitz-John Porter.

"I sit in my tent and think but it seems like a horrid dream," William L. Berry wrote. "Hundreds of my companions gone, victims to the strife, never to return. I have but to step to the door and look at those that are still left and then the sad reality looms before me in its darkest form."

"I sit in my tent and think but it seems like a horrid dream," William L. Berry wrote. "Hundreds of my companions gone, victims to the strife, never to return. I have but to step to the door and look at those that are still left and then the sad reality looms before me in its darkest form." Camp nearJames River, Virginia

July 5, 1862

A week of horrors has just passed.Future historians will dwell upon the scenes of the past week as the mosteventful and bloody since the christening of the western hemisphere. I sit inmy tent and think but it seems like a horrid dream. Hundreds of my companionsgone, victims to the strife, never more to return. I have but to step to thedoor and look at those that are still left and then the sad reality loomsbefore me in its darkest form.

I look to the next regiment and seebut 150 guns stacked where there used to be 800 and again, I know it is not adream. But the saddest of all is when I look for a dear friend and fear, too,he has fallen. What I have witnessed I hope and pray never to witness again. Iwill, in as plain a manner as possible, tell you what I have seen, so that youmay judge what war is. I told you what I saw at West Point and HanoverCourthouse, but they are not to be compared to the struggle of the past fewdays.

We had encamped in a most beautifulgrove. Everything has been done to make ourselves comfortable as we all were ofthe opinion that our stay at this point should be extended into the summer. Thethird day of our stay here [June 26] was drawing to a close, the men loungingunder the luxuriant foliage of the adjacent trees all satisfied that all waswell. When to the utter surprise of all, we heard the first sergeant call themen to fall in with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, and three days’ rations.What could it mean? None could tell, but the order was quickly obeyed and inone hour from the time the order was read, the line was formed and under way.

I stood by the road as they filed outand it was the last time that I saw half of them. I was not ordered off withthem, so I, as well as others that were left in camp, supposed that they werebut going on picket or fatigue duty and thought nothing about it, but duringthe night, the rumbling of the wheels of cannon could be continually heardwhile the clattering of horses feet galloping along the road kept up acontinual noise but with the early morn, a different aspect of affairspresented itself. Before it was clearly light, I received an order to pack upall our hospital furniture, send the sick over the Chickahominy as quickly aspossible, to get everything off in a half hour, and if I could not get all offin that time to be off myself without delay.

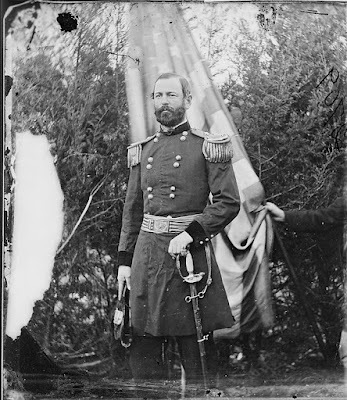

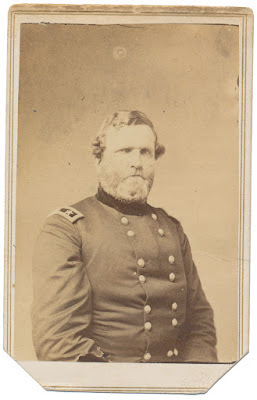

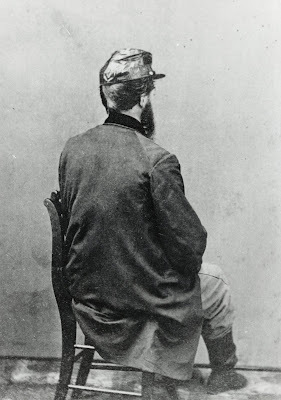

Major General Fitz-John Porter, commanding the 5th Army Corps during the Seven Days

Major General Fitz-John Porter, commanding the 5th Army Corps during the Seven DaysThis order came from the brigadesurgeon and had to be obeyed; but we worked with a will and before the timeelapsed, we were off. But hardly had we got away from the spot before theshells from the enemy’s guns nearly reached the spot we were leaving. We putspurs and whips to our horses and were soon over the Chickahominy, disposing ofthe sick and stores as directed.

I hastened back to the scene ofconflict. I found everything in battle order, artillery placed upon commandingpositions, ably supported by infantry, while the cavalry were disposed of aswas proper. I found our regiment and brigade and after carefully viewing theposition of our forces and knowing well the lay of the ground at thatparticular point, instantly became satisfied that we were in a criticalposition. Especially if the enemy was in force as strong as we supposed theywould be and if they attempted to break through our lines. One advantage we hadover them was our superior force of artillery, the mightiest arm of war.

We waited with almost breathlessanxiety for the commencement of the fight. We had not long to wait. Theregiment was lying upon the ground for greater safety when suddenly a reportwas heard and with it a terrific screech from the left of our column. Uponhastening to the spot, we found that a shell from the enemy’s gun has burstupon three of our men, inflicting the most horrible and painful wounds. Theywere removed.

All was now excitement, it being thefirst time that our regiment was ever under actual fire. Delay was nowimpossible. We knew their position, although hidden by a thick growth ofVirginia pine, and our batteries began to belch forth their own hail with theutmost rapidity. It was returned with spirit and cannonading was kept up forupwards of two hours without intermission and strange to say, without much lossupon our side. One captain in our regiment was the only one that fell afterthat first shell; but at this point, things took a different turn.

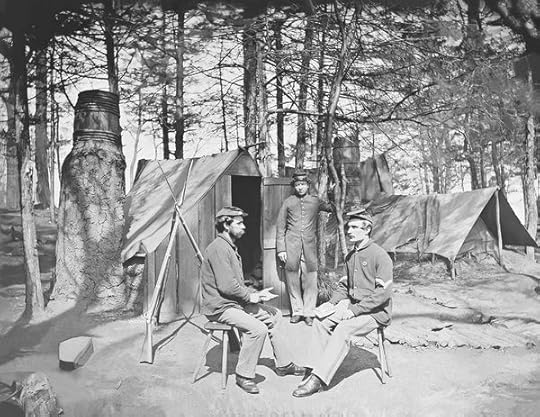

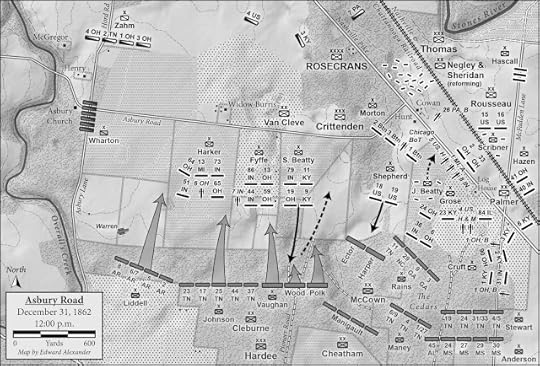

The 16th Michigan held a position in the second line on the far left of the Union line during the sunset attacks by the Confederates at Gaines Mill. These assaults finally broke the Union line as Berry describes in his letter.

The 16th Michigan held a position in the second line on the far left of the Union line during the sunset attacks by the Confederates at Gaines Mill. These assaults finally broke the Union line as Berry describes in his letter. Musketry began to be heard on our leftand our lookout, who was up in a thick tree, said that they were advancing bythe left. Orders were instantly given for us to “left face, forward march” andwe soon met them face to face. Shots were instantly exchanged. At this point,our regiment suffered heavily as about 50 fell at the first fire. We stood ourground for awhile but they succeeded in taking a battery of artillery from us bywhich we were so weakened that we were forced to retire, leaving our wounded.

But the enemy’s success was onlytemporary; for we soon rallied and went up by the left flank and charged onthem, succeeding in taking back our ground, although at a terrible loss oflife. The fighting again became general, the cannons roaring, shells burstingin the air, balls whistling with their shrill music by to us to commit havocupon those in our rear while the volleys of musketry sounded like the distantapproach of a whirlwind, the echo like the wail of departed spirits singing asad requiem to those just fallen.

The enemy was in force much strongerthan ours. They regularly relieved every 15 minutes while our men had to standtheir ground amidst the most galling fire. They crowded us up and again we fellback, this time in regular order. We were now reinforced by what is called theIrish Brigade. General Porter rallied the men, formed them upon a color line,and back went our thinned ranks to battle against their unequal forces oncemore.

The men retained their courage. We now came up to them andpoured in a volley. The order was given to “load and fire at will” but ourgeneral, seeing that the odds were against us, concluded to try once more. Theorder was given to charge. Every gun came to a shoulder and then to a charge,and way we went with a yell that ought to frighten old Nick. The enemy fled.

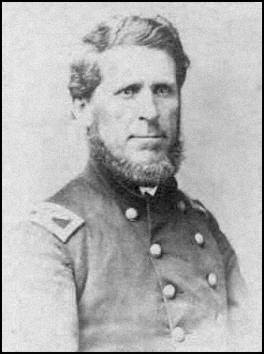

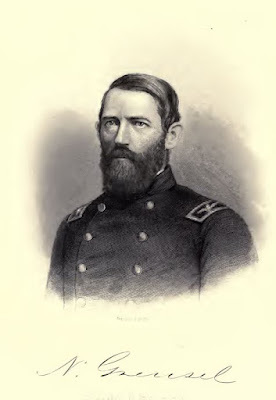

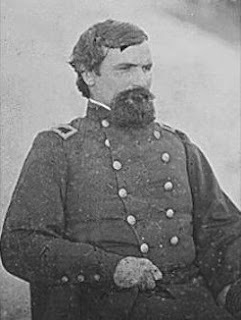

Colonel Thomas B.W. Stockton

Colonel Thomas B.W. Stockton16th Michigan

Prisoner of War

The general, seeing them fly and seeing the evening shadescoming on, ordered us to retire. So, the order to about face was given. Wegladly obeyed the order and retreated quickly across the Chickahominy, leavingthe enemy in possession of the field and more than all, in possession of thewounded. The greatest loss we sustained was the loss of our gallant and braveColonel [Thomas Baylis Whitmarsh] Stockton; he is a prisoner. Two captainsfell, three were wounded, several lieutenants were killed and wounded, but acomplete list you will doubtless see in the papers.

[Colonel Stockton’s horse was shot out from under him then hewas captured. Stockton, an 1827 graduate of West Point, would be exchanged inAugust for Colonel Lewis Burwell Williams of the 1st Virginia, an 1855graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and former assistant instructor intactics at V.M.I. Williams had been wounded and captured at Williamsburg on May5, 1862.]

The thought came to my mind: what did all this mean? WasMcClellan surprised and was the vast army that the government had been socarefully nursing for the past year suddenly to be put to rout and driven back?Was all the admirable plans to be defeated and was the enemy to still holdtheir sway? I pondered over it all night and could come to no reasonable conclusionwhy we should be so defeated and driven from the ground that we had held for solong a time. I’ll confess that for the first time, my confidence in McClellanwas shaken but felt satisfied that all would turn out for the best.

At the approach of morning, I left the ground where I hadlaid all night and went to the bridge crossing the river. This I found stronglyguarded and preparations made to destroy it. Suddenly, a loud report was heardand all communication over the Chickahominy was cut off. Things now looked moregloomy and mysterious than ever. All our forces were withdrawn from over theriver, all our baggage train had been hurried away, all the commissary stores (ofwhich there was a vast quantity) had been destroyed. Thousands of our woundedwere in the hands of the enemy and everything looked as if we were about tomake preparations for another fight or march, those who were left filling theirhaversacks with bread and getting the full amount of cartridges.

Union forces on the retreat. "Everybody looked gloomy and everybody supposed that all was wrong and that our army would be routed and broken up," Berry lamented.

Union forces on the retreat. "Everybody looked gloomy and everybody supposed that all was wrong and that our army would be routed and broken up," Berry lamented. Everybody looked gloomy and everybody supposed that all waswrong and that our army would be routed and broken up. I passed along lookingfor our regiment from which I had strayed. I stopped a moment under the shadeof a tree to rest. While there, a colonel came up and asked a question which Ianswered. We got into conversation and I asked him if things were not lookingblue. He seemed astonished at the question. “Truly, do you not understand themove,” he asked. I told him it looked strange and would like to be informed.

He then asked me what good advantage it would be to staywhere we were. I told him that it was close to a water communication withWashington and a good place for making an attack on the Rebel capitol. “Yes,that’s true, but is not the James River a better means of communications and abetter base of operations than where we were?” That cleared my eyes. I saw thewhole game in a moment and told him so and we parted, he to fall into the ranksand I to let you know it.

The 16th Michigan lost 49 killed, 116 wounded, and55 missing at Gaines Mill, a total of 220. Major Norval E. Welch assumedcommand of the regiment after Colonel Stockton was captured.

To learn more about the Battle of Gaines' Mill, please check out these posts:

With the Jasper Grays at Gaines Mill (16th Mississippi)

Carrying the Colors of the 5th Texas at Gaines Mill

Louder than the Bolts of Heaven: With the 1st Michigan at Gaines Mill

A Promise Kept After Gaines Mill (1st Michigan)

More in the Wind Than We Bargained For: The Seven Days with the 3rd New Jersey

The Great Skedaddle: With Berdan's Sharpshooters During the Seven Days (1st U.S. Sharpshooters)

Source:

Letter fromHospital Steward William L. Berry, 16th Michigan Volunteer Infantry,Ingersoll Chronicle (Ingersoll, Ontario, Canada), July 25, 1862, pg. 2

A complete transcription of all of Berry's letters to the Ingersoll Chronicle was published as A Canadian in the Army of the Potomac: The Letters of William L. Berry of the 16th Michigan published in 2024. Kim Crawford's regimental history of the 16th Michigan is also worth a perusal.

August 28, 2025

Catching a Hatful of Bullets: With the 2nd Minnesota at Chickamauga

The 2ndMinnesota fought on four separate occasions during the two days of the Battleof Chickamauga. One soldier recalled that the hottest fighting occurred on themorning of September 20th when the regiment was trying to hold theleft of the Union line.

“Here the Rebels came up on our left flank,” he noted. “Wechanged front to meet them with the 9th Ohio in advance and were immediatelyordered to lie down. Here was the hottest place for bullets I ever saw. Itseemed as though we could have held up our hats and caught a hatful. The 9thOhio broke, but rallied in our rear and for a few minutes, the fighting wasterrific, the Rebels hurling mass after mass to the front but in vain. OurMinies could go through four ranks at short range but they could not stand theslaughter and fled."

"The 9thOhio and 87th Indiana charged across the field in front, the 35thOhio passed on and we, according to orders, caught up the rear. At the edge ofthe woods in front we halted and were again ordered to lie down. Here we werein exact range of a Rebel battery but a few rods in advance in the road. Theypoured in grape and canister and here Ambrose Palmer was killed; he was struckin the side and scarcely moved except to slightly raise one hand which hedropped very quietly by his side," he wrote.

This following letter, written by anunknown soldier of Co. B of the 2nd Minnesota, first saw publicationin the October 24, 1863, edition of the Rochester City Post.

Chattanooga,Tennessee

October 5,1863

Thinking a plain statement of thehistory of Co. B of the 2nd Minnesota during the days of the 19thand 20th of September 1863 might not be uninteresting to the friendsof those who shed their blood and laid down their lives on that tryingoccasion, I will relate its principal incidents.

On the night of the 18th at6 p.m., we were ordered to march left in front with 20 extra rounds ofcartridges. We marched all night and in the morning arrived in the vicinity ofthe enemy who was endeavoring to cut off our communication with Chattanooga. Wehad half an hour in which to make coffee then we marched off to the right ofthe road, threw out skirmishers, formed our line of battle and advanced a milebefore halting in position. The skirmishing soon commenced on the right of thedivision, rolling towards the extreme left, the position of the 2ndMinnesota. The first attack was a light one, the regiment losing only two orthree wounded and was repulsed with ease.

For half an hour scarcely a gun wasfired when it suddenly opened in our front and rather to the left, apparentlynearing us rapidly. Suddenly, the woods in our front swarmed with a confusedmass of our men, running rapidly to the rear. Upon inquiry, we found it was theThird Brigade, U.S. Regulars, belonging to Rousseau’s division. Our officerscalled upon the men to stand, but they showed no disposition to move but laydown quietly and cursed the Regulars as they retreated over them.

Hardly had the Regulars passed whenthe Rebels came down. For 20 minutes the fighting was fierce; when the Rebelsgave back, the 9th Ohio charged and retook the 5thRegular Battery which the Regular Brigade had lost. In this fight,Co. B lost Samuel D. Calvert. A few minutes later and the Rebels appeared onour left flank. We were ordered to change front by the left flank. The orderwas given late and we executed it under a hot fire and lost the heaviest of theday. But we soon opened on them and the 4th U.S. Battery, belongingto our brigade, poured in a terrible fire.

The left of the regiment was orderedto fall back 20 paces; they did so, relined themselves, and opened once more,pouring in a left oblique fire with such effect that in a few minutes theRebels fell back and with us, the fighting for the day closed. We learned fromprisoners and deserters that we had been fighting Walker’s division ofLongstreet’s corps. That evening, we marched off to the right and rested asbest we could in the bitter cold.

Until 9 o’clock the next morning,scarcely a shot was fired. We moved to the front, double column closed in masswith our brigade in reserve. By and by there came an occasional shot from thewoods in front, gradually becoming sharper and quicker until the woods roaredwith musketry, accompanied with the booming of cannons and the occasionalstriking of projectiles rather nearer to our closed ranks than was agreeable toyour humble servant. But our men were pushing them, and we moved on into thewoods which we crossed and struck the open field beyond.

Here the Rebels came up on our leftflank; we changed front to meet them with the 9th Ohio in advanceand were immediately ordered to lie down. Here was the hottest place forbullets I ever saw. It seemed as though we could have held up our hats andcaught a hatful. The 9th Ohio broke, but rallied in our rear and fora few minutes, the fighting was terrific, the Rebels hurling mass after mass tothe front but in vain. Our Minies could go through four ranks at short rangebut they could not stand the slaughter and fled. Here Ellis A. Comstock waswounded.

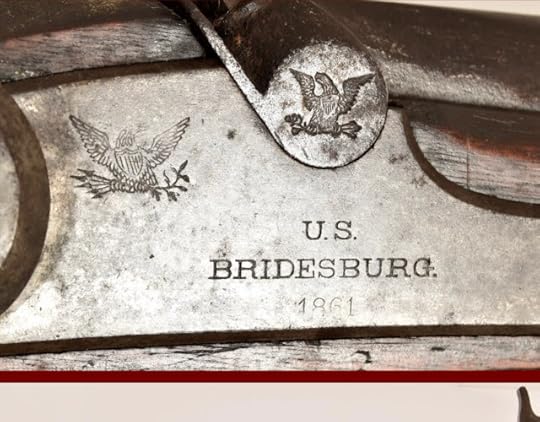

At Chickamauga, the 2nd Minnesota was armed with quite the mix of long arms including M1861 Springfields whose lockplate is shown above, along with Enfields, Mississippi rifles, a few Colt's revolving rifles, three .69 caliber altered to percussion muskets and a solitary Lorenz!

At Chickamauga, the 2nd Minnesota was armed with quite the mix of long arms including M1861 Springfields whose lockplate is shown above, along with Enfields, Mississippi rifles, a few Colt's revolving rifles, three .69 caliber altered to percussion muskets and a solitary Lorenz! The 9th Ohio and 87thIndiana charged across the field in front, the 35th Ohio passed on and we, according to orders, caught up the rear. At the edge of thewoods in front we halted and were again ordered to lie down. Here we were inexact range of a Rebel battery but a few rods in advance in the road. Theypoured in grape and canister and here Ambrose H. Palmer was killed; he wasstruck in the side and scarcely moved except to slightly raise one hand whichhe dropped very quietly by his side.

The 35th Ohio drove themfrom our front and we moved up about 20 rods and lay down once more. Here the35th Ohio was driven back and we were quickly engaged in one of thefiercest fights of the day. From this time, the discouraging part of the daycommenced. The regiment on the left (I did not get its name) gave way; theRebels began to flank us and we were ordered to fall back which was done bypassage of lines to the rear until we took up a new position about 4 o’clockhalf a mile to the rear of Missionary Ridge.

The regiment on our left had formed arail breastwork and was prepared to hold it. The 9th Ohio formed onour left and the 35th Ohio on the right. The Rebels soon advancedand for two and a half hours it was hard telling how it would go; the Rebelsplanted their colors within a rod of the breastworks on our left and were repeatedlydriven back. Cartridges became exhausted, the boxes of the dead were searchedand emptied and every available means resorted to for ammunition. It was almostdark when the Rebels withdrew and left us in possession of the hill.

Half an hour later and we took up ourline of march for Rossville where we rested for the night and had time to countthe dead, the wounded, and the missing. We went into the fight with 37 men onSaturday morning; we came out on Sunday evening leaving 5 of them dead on thefield, 13 wounded, and 2 taken prisoners. Since our return to Chattanooga, HezekiahG. Smith lost a finger by a shot from a sharpshooters while going on picket.

Second Minnesota monument which is located at Horseshoe Ridge at Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Battlefield.

Second Minnesota monument which is located at Horseshoe Ridge at Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Battlefield. It is not for me to relate more thanthe simple fact of what was done; what is true of Co. B is true of theregiment. Every man did his duty and the memory of our dead shall by sacredforever. We know they fought with unflinching determined bravery and whiletheir friends mourn them, let them be assured that this company mourns withthem for long association had made their vacant places in the ranks as sacredas the vacant chair of the family hearthstone.

The regiment lost in the battle 153 killedand wounded. Every officer did his duty: Colonel [James] George was cool and steady,Lieutenant Colonel [Judson] Bishop was everywhere in the right place and in theright time, and Major [John B.] Davis has a look that would make a cowardfight. Captain Abram Harkins, when he left the field with his arm left broken,told the boys to fight to the last. All our field officers had their horsesshot under and all were slightly wounded, but not seriously. [Captain Harkinswould lose his left arm to amputation and resigned his commission June 20,1864.]

To learn more about the Battle of Chickamauga, please check out my Battle of Chickamauga page which features dozens of accounts from both Federal and Confederate combatants.

To learn more about the service of the 2nd Minnesota Infantry, please check out these posts:

Nip and Tuck with the 2nd Minnesota at Mill Springs

A Tale of Two Colonels: A Blue and Gray View of Mill Springs

A Librarian's First Battle: At Mill Springs with the 2nd Minnesota

A Fight for Corn: Eight Medals of Honor Awarded at Nolensville

Source:

Letter fromSoldier of Co. B, 2nd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry, RochesterCity Post (Minnesota), October 24, 1863, pg. 2

August 27, 2025

A Grandstand View of Missionary Ridge: A Voice from the 10th Ohio

Stationed in Fort Wood in Chattanooga as officer of the day, Lieutenant Alfred Pirtle of the 10th Ohio enjoyed a grandstand seat of the Army of the Cumberland's daring and successful charge upon Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863.

"At 3 o’clock or later, orders were issued from Orchard Knob, General Thomas’s headquarters, for the line in front of Missionary Ridge to advance. It is beyond my powers of description to give any idea of the excitement we all felt at Fort Wood, from our heart of hearts, as we heard the first shots that told the hot work that was coming. The firing broke forth at all points almost at the same moment. Fort Wood joined in, with the heaviest guns on the batteries at Bragg’s headquarters, more than two miles away on the summit of the ridge. The enemy’s batteries threw shells at our men, who were charging across the open at the entrenchments, while we could see the Rebels rushing from behind the crest of the ridge to line the breastworks, thrown up along the very highest part of the ridge, from battery to battery, six of which were playing on our men in the fields below," he remembered.

"For a few moments the roar of the battle was tremendous and incessant and then we saw the Rebels leaving the rifle pits, scampering for the second line. Our men paused for a few moments under cover, charged the second line and took a few prisoners. Here the fire of the enemy’s batteries was very hot, when to seek protection from it our officers led the way to the ridge. Now commenced the most exciting and brilliant feat of arms yet performed during the war. The ridge is about 500 feet high, very steep, free from underbrush where the assault was made, having been cleared, as I before remarked. Several wagon roads led to the top, by which then Rebs had communication with the camps below, but these roads were raked by artillery. Here and there sharp ridges of only a few feet in altitude broke the general formation of the slope, affording protection against flanking fire to a few men who availed themselves of the gullies between."

Lieutenant Pirtle's letter, written just two days after Missionary Ridge, first saw publication in Volume 6 of the papers read to the Ohio Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

Captain Alfred Pirtle of the 10th Ohio Infantry lived until 1926, writing extensively of his experiences during his service as a soldier in the Army of the Cumberland.

Captain Alfred Pirtle of the 10th Ohio Infantry lived until 1926, writing extensively of his experiences during his service as a soldier in the Army of the Cumberland. Camp of 10thOhio Infantry, Chattanooga, Tennessee

November 27,1863

We have gained a great victory andshown the world what can be done by science and bravery. On the morning of the23rd, it was expected that we would commence the battle, but itseems that General Sherman had not crossed the Tennessee River north ofChattanooga, as was expected, and the program was delayed. During the forenoon,the steamer Dunbar which the enemy had burned at the wharf here whenthey left in haste for Georgia, had been rebuilt by mechanics from our army,was engaged in ferrying at the wharf, where our pontoon bridge had been sweptaway by Rebel rafts sent down the night before.

At 1:55 p.m., skirmishing commenced infront of Fort Wood, which was near the left of the ground occupied by the 4thArmy Corps. This seemed to be the signal for a general advance, as our forcesmoved from our lines simultaneously from all points in the front ofChattanooga, throwing out their skirmishers and grandly, slowly, and surelyoccupying Rebel ground once more. From a commanding elevation in the center, Isaw this magnificent panorama of war, unexcelled by anything I ever imagined. Facingto the enemy, the heavy guns from Fort Wood boomed at intervals and the rushand roar of their projectiles, overpowering the minor arms, gave dreadful noteof our coming.

Small arms sounded in the woods eastof the Atlantic & Western Railroad embankment and our men were in the enemy’slines on the left. The center swung out in fine order, slowly as I said, as ifexpecting sharp resistance, but still advancing, their long black linesbristling and flashing with bright arms. From Fort Negley, a long line ofartillery opened and rattling shells exploded and crashed in the woods in frontof the troops advancing from our center. Those batteries cease, for our firstline is in the woods, the second in the open ground, massed and ready to movein any direction. Now our right is going ahead, slowly also, over disputedterritory, but without meeting opposition, reaching the timber where the enemyformerly picketed.

The enemy’s big gun mounted on the topof Lookout Mountain now joins in, to drop shells at our spiteful battery on MoccasinPoint, which is blazing away at a column of Rebel troops on the slope of themountain descending to the valley on the road toward their right. A Rebelbattery away toward the enemy’s right on Missionary Ridge opened fire on ourmen near the left, who have occupied the rifle pits where they captured aGeorgia regiment. This artillery fire from the enemy brings answering fire fromone of our batteries; the Rebels throw forward a larger force and our men wereobliged to retire. Not long do they rest, but, reinforced and encouraged, theyreturned to the fray, reoccupied the ground and remained.

While this is going on the droppingfire to the right indicated that skirmishers are moving; the fire increases,declines, growing more and more distinct, until at dusk a half mile advance hasbeen fought over, driving the enemy that far. The results are reported ashighly satisfactory; 200 prisoners taken and much ground secured with triflingloss. Both armies kept quiet during the night.

General Joseph Hooker and his staff in Lookout Valley in 1863

General Joseph Hooker and his staff in Lookout Valley in 1863The morning of the 24th wasdamp and disagreeable, promising rain. About noon, a brisk skirmish rattledfrom the western slope of Lookout Mountain on our extreme right, where GeneralHooker’s army corps had been encamped so long. Behind the slope of the point ofthe mountain, hidden from us in Chattanooga, a fierce fight was going on, but noone could tell to whom was the advantage. The deep roar of the artillery frombatteries in Lookout Valley reverberated from the sides of Raccoon and LookoutMountains, and curling wreaths of smoke marked where their shells burst in thewoods.

A lull occurred and everyone anxiouslygazed at the open ground near a large white house on the northern slope in fullview, expecting to see some signs of the fight, stragglers or wounded men, butnone of them appeared. Bragg had not looked for an attack on his left, for aletter or dispatch to one of his generals had been captured, saying we weremassing on our left, and he was concentrating his troops there. The supports wesupposed would soon go to the enemy at length appeared on the eastern slope ofLookout Mountain, concealed from our battery on Moccasin Point. The fightreopened on the western slope and grew heated; hearty cheers and rattlingvolleys; a silence and then, a rush of Rebels across the open fields, hurryingindiscriminately from our victorious lines.

Into this mass of fugitives our gunsfrom Moccasin Point and Fort Negley poured shells, ceasing to fire when ourbluecoats emerged from the woods. Forming line of battle, the first regimentadvanced at double quick across the field, their colors borne 30 yards beforethem, and amid the shouts of our army, who saw the gallant deed, took the whitehouse, made good their hold on the enemy’s rifle pits and remained under heavyfire. A second regiment soon joined them, and the enemy’s supports came up toolate. The 40th and 99th Ohio regiments are said to havedone this gallant deed, and, whoever they were, they deserve to be rememberedwell by their country, for it filled all our army with admiration. A tremendousrain and mist soon came down, hiding the fight from us, but the steady rattleof musketry behind the veil showed a stubborn resistance from the enemy. Thisfire was kept up, dying away at times, again to be renewed and lull again,until about 10 p.m. when it ceased.

The rain was over by dusk, giving wayto a most splendid moon about full, and the night turned very cold before day.On Lookout Mountain, over the space newly gained so bravely, gleamed a line offires, beacons of loyalty, carrying glorious news and encouragement to GeneralGrant’s army that lay at the mountain’s foot. Early in the night from the eastslope of Lookout Mountain, the side where the two lines of foemen lay fighting,bright sparkles of vivid light, quick and bright as lightning, gleamed at eachshot, sometimes so frequent as to almost illuminate the spot where the briskskirmish was going on, kept up by the enemy to enable them to extricate the forcesfrom the summit of Lookout and hide the rattling of wagons that all night longwere hurrying down the big guns and supplies.

The 25th was bright andcool, bracing, and exhilarating. General Sherman’s corps had made good theirfooting on the night previous, as their long lines of fires gleamed on thehillside at the north end of Missionary Ridge, opposite the campfires of theenemy on a knoll just south of theirs. About 8 a.m., the battle began onSherman’s front. Fort Wood had a commanding position, giving a view of thewhole lines of both armies, and we could see two batteries on Sherman’s frontat work, as well as an answering one from the enemy; but as both remainedstationary, we concluded neither side was gaining ground. The sounds ofmusketry only came at intervals, borne on the wind, but the boom of the cannonfollowed regularly on each shot.

The 11th Army Corps movedfrom its place in front of Fort Wood about 9 o’clock, crossed Citico Creek,advancing under skirmishers toward Sherman; for we could see the enemy’s columnhurrying along the top of Missionary Ridge to mass on their right, and all wereapprehensive of an attack on our extreme left or Sherman. While these movementswere going on, a sharp fire opened up on General Thomas’s front, as if he wasgoing to take the enemy’s rifle pits, eliciting a heavy artillery fire from theridge, replied to by one of our batteries on Orchard Knob, Fort Wood, and a batteryin Sheridan’s division. This advance drove the enemy from the woods and forcedthem to retire on their entrenchments in the open ground near the foot of theridge.

Our attention was drawn from ourimmediate front toward the left again where an effort was beginning toward thetop of the ridge. A line of battle could be seen moving over an open field, upa hill, directed on a Rebel battery that that had been playing on our left upto this time. Up went the regiment until near the crest where it halted to takebreath and throw our skirmishers toward the enemy. A strong support moved upand the two lines closed upon the foe, followed by a third line. When thelatter arrived near enough to be in supporting distance, a brisk fire opened, acharge was soon made, the Rebel battery fired, reinforcements to the enemyrushed along the ridge and after a hard struggle we see with deep sorrow ourmen fall back down the hill.

One of our batteries pitched into thepursuing forces, who are checked, and finally fall back in turn. Forming again,our undaunted warriors, after a rest, try another line of approach farther toour left, fight with renewed vigor as well as a determination that drives allbefore it, giving us possession of the hill, but at considerable loss. From thefact that Bragg had massed the majority of his troops on his right, the fightthere was not attended on our side with the same amount of success as followedour operations on his center and left.

General Hooker, meantime, had been occupiedswinging round the right of our line from Lookout Mountain on Rossville, adistance of 4-5 miles, feeling his way, but making good progress, for about 3 o’clockword went round Fort Wood that ‘Hooker was in Rossville’ and everyone expectedsomething great would soon happen, but where the blow was to fall no oneappeared to know. By reviewing the position, it will be observed that Grant hadso maneuvered that Bragg had concentrated most of his troops on the north endof Missionary Ridge, while the national troops were driving back his center andleft. Almost a parallel case to ours at Chickamauga, only the wings werereversed. Events subsequently showed he had no Thomas to save his left. So confidentwas he of driving us back that he was at his headquarters until our men were onthe ridge within rifle shots of him and had taken some of his artillery.

General George H. Thomas

General George H. Thomas"Rock of Chickamauga"

Since occupying the ground inSeptember, the enemy had cut the timber off the valley for more than a milefrom the foot of the ridge and also trimmed the slopes of the hill so as togive range to their artillery, more than 30 pieces of which bore on the groundover which our troops had to advance if an assault on the ridge was everattempted. Not far from the timber, from which our lines debouched, a line ofrifle pits was thrown up and again between them and the hills heavy breastworksof logs and stones, earth, and other objects had been erected to protect theircamps.

At 3 o’clock or later, orders wereissued from Orchard Knob, General Thomas’s headquarters, for the line in frontof Missionary Ridge to advance. It is beyond my powers of description to giveany idea of the excitement we all felt at Fort Wood, from our heart of hearts,as we heard the first shots that told the hot work that was coming. We, not knowing what vast supports might be near the top of the ridge, hidden from our view.From our outlooking position on Fort Wood we could see the movements made onthe hillside, as it lay directly before us, though the first push of our braveboys was concealed by the woods, whence they had driven the enemy about 1 o’clockin the morning.

The firing broke forth at all pointsalmost at the same moment. Fort Wood joined in, with the heaviest guns on thebatteries at Bragg’s headquarters, more than two miles away on the summit ofthe ridge. The enemy’s batteries threw shells at our men, who were chargingacross the open at the entrenchments, while we could see the Rebels rushingfrom behind the crest of the ridge to line the breastworks, thrown up along thevery highest part of the ridge, from battery to battery, six of which wereplaying on our men in the fields below. For these details we had to rely onglasses to bring them out, because Fort Wood is more than two miles from theridge.

For a few moments the roar of thebattle was tremendous and incessant and then we saw the Rebels leaving therifle pits, scampering for the second line. Our men paused for a few momentsunder cover, charged the second line and took a few prisoners. Here the fire ofthe enemy’s batteries was very hot, when to seek protection from it ourofficers led the way to the ridge.

Now commenced the most exciting andbrilliant feat of arms yet performed during the war. The ridge is about 500feet high, very steep, free from underbrush where the assault was made, havingbeen cleared, as I before remarked. Several wagon roads led to the top, bywhich then Rebs had communication with the camps below, but these roads wereraked by artillery. Here and there sharp ridges of only a few feet in altitudebroke the general formation of the slope, affording protection against flankingfire to a few men who availed themselves of the gullies between.

Up the steep slope charged Sheridan’s,Wood’s, and Baird’s divisions in full sight, in the order named, from right toleft. Twenty pieces of cannon under General Bragg’s personal supervision rainedgrape and canister at our gallant fellows, while thousands of small armscracked from behind the breastworks. We see the glancing arms of our linesslowly creeping up and we mark the dear old flags so bravely blowing in theenemy’s face.

A few yards at a time each man climbed and when exhaustedthrew himself down behind a tree, stone, stump, or other cover to get hisbreath. High up the hill one brave fellow has borne his stars and stripes untilhe falls for want of breath; lying there, he waves and waves his flag and wefancy we can hear his comrades cheer for he does not lie long alone. We see mencrawling, climbing up to him, past him, and soon he rises, runs forward toplant his flag in or among the enemy, almost in their ranks. Here he pauses,flaunting his flag at the Rebels, who fire at him in vain. Clustering around wesee men forming and gradually the line becomes formidable. Another flag soonstands near the first, and then the two regiments approach the top, theircenters forming the point of a wedge toward the enemy.

Swinging the wings around, they clambered over thebreastworks and are face to face with the foe, who in superior numbers stretchalong both ways. But they are wavering and their line is thin out towards theflanks, while our strengthens every moment, fighting furiously. At anotherpoint, up go the supports, straining every nerve. We, who stand watching themso anxiously, see the large numbers of the enemy fighting those already up andwe tremble lest the supports do not get there in time.

They are in at the death. Five standards blow out in thenorth wind, a splendid charge follows, and our men disappear behind the ridge,in pursuit of the Rebs. Those who participated in this grand achievement toldus that such cheering was never before heard as pealed from thousands ofthroats ‘Chickamauga, Chickamauga’ followed in thunder tones the flying foedown the eastern slope where hundreds of them were captured.

The fighting on Sherman’s frontcontinued till dark but we could not see that he gained any ground from wherewe stood.

Sources:

“Three MemorableDays- A Letter from Chattanooga, November 1863,” First Lieutenant Alfred Pirtle, Co. F, 10th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Sketches of War History,1861-1865. Papers Prepared for the Commandery of the State of Ohio, MilitaryOrder of the Loyal Legion of the United States. 1903-1908. Volume 6.Cincinnati: Monfort & Co., 1908, pgs. 35-46

August 25, 2025

The Battle Became Interesting in the Extreme: With the 84th Illinois on Lookout Mountain

The Chattanooga Campaign might not have been the hardest fought one the 84th Illinois ever participated in, but the scenery proved awe-inspiring as recalled by Lieutenant Lewis N. Mitchell of Co. A.

"The morning of November 25th dawned clear and beautiful but cold. We were at such an elevation that the surrounding country lay fair to view. Chattanooga, the Tennessee River in its devious course, and our camps; oh, how beautiful the sight! But what do we see to our left? The Rebel works and camps are in plain view and there are long lines of bluecoats advancing across the plain towards Missionary Ridge. Now we see their colors and now the boom of artillery and the rattle of musketry and they are hidden from view. The old flag waves from Lookout Point and cheer after cheer rolls off across the valley below," he wrote.

Lieutenant Mitchell’s diary of theChattanooga campaign, featuring insights into the fighting on Lookout Mountain,Missionary Ridge, Ringgold Gap, and a visit to the Chickamauga battlefield, waspublished on the front page of the Christmas Day edition of the MonmouthAtlas from Monmouth, Illinois.

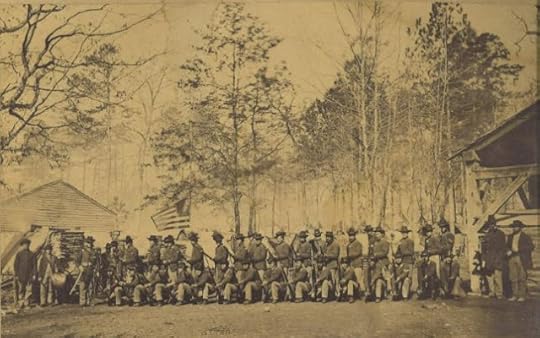

Company E of the 84th Illinois poses in their camp at Murfreesboro in early 1863. The men had just recently participated in the Battle of Stones River and had the Tullahoma campaign, Chickamauga, and Lookout Mountain ahead of them through the balance of the year.

Company E of the 84th Illinois poses in their camp at Murfreesboro in early 1863. The men had just recently participated in the Battle of Stones River and had the Tullahoma campaign, Chickamauga, and Lookout Mountain ahead of them through the balance of the year. On the morning of November 23, 1863,we were encamped at Whiteside, Tennessee. We had reveille at 5 a.m. and at 7the bugle sounded to strike tents and we were soon packed and rationed for themove. We marched at 10:30 a.m., taking the road leading to the point of LookoutMountain. We arrived within one mile of Lookout at dark and reported to GeneralHooker. We camped in the valley at dark for the night after a march of 9 miles.

Reveille came at 4 a.m. on November 24th;the morning was chilly, foggy, and sprinkling rain making it very disagreeable.We moved at daylight to the creek west of Lookout and formed in line of battle withCompanies F and G thrown forward as skirmishers, advancing in line to within 30yards of the Rebels outer rifle pits. This brought on a brisk engagement aswould be supposed. The regiment waded a pond in the move, varying in depth from2-4 feet and cold. Walker’s division of Rebels occupied Lookout and our musketssoon brought out a regiment or two of them to prevent our crossing the creek.

We constructed rude breastworks oflogs and stone, felling some trees. Our sharpshooters and skirmishers kept themclose in their works and along the railroad the action lasted in this shape forsome 2 hours when a division of the 15th Corps had succeeded (bydrawing their attention there) in flanking them. The battle then becameinteresting in the extreme as the whole field could be taken in one view.Musketry and artillery were both freely used and when the Rebels found theywere flanked with our fire in front, they had to lie still in their pits and betaken prisoners. They did not try to retreat in line at all and it became a routor skedaddle and our regiment alone took 126 prisoners with 4 commissionedofficers. At the top of the ridge, they railed and formed a new line and heldus at bay till midnight when they got up and dusted again. We remained in lineof battle that night. [To read more about the November 24th fighting on Lookout Mountain, please check out "The Flag Capturing Machine: The 149th New York and the Chattanooga Campaign," and "Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion: An Iowan on Lookout Mountain."]

The morning of November 25thdawned clear and beautiful but cold. We were at such an elevation that thesurrounding country lay fair to view. Chattanooga, the Tennessee River in itsdevious course, and our camps; oh, how beautiful the sight! But what do we seeto our left? The Rebel works and camps are in plain view and there are longlines of bluecoats advancing across the plain towards Missionary Ridge. Now wesee their colors and now the boom of artillery and the rattle of musketry andthey are hidden from view.

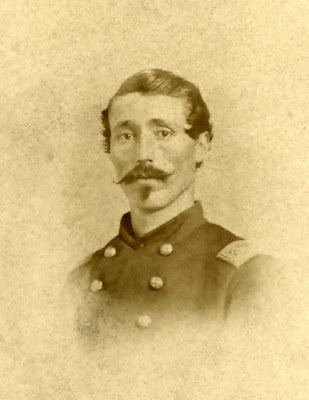

Colonel William Grose

Colonel William Grosebrigade commander

Our loss was light on Lookout- about150 in killed and wounded. Our prisoners number nearly 3,000 and 4 pieces ofartillery. The old flag waves from Lookout Point and cheer after cheer rollsoff across the valley below. Hooker is with us in person and orders a reconnaissancetowards Missionary Ridge. Our regiment moves out with our company (A) asskirmishers. We moved over a low hill and the skirmishers capture 18 prisoners,4 boxes of guns, clothing, meal, flour, beans, tents, officer’s mess boxes,etc. that were left in their precipitous flight. A vast amount o stores areburning near the Rebel stronghold.

Osterhaus’s division passes us on theroad to Rossville and the advance becomes engaged at the pass. At 3 p.m., wedrive them in in column, then move by the left flank and in 5 minutes we arehotly engaged. The 9th Indiana and the 4th Iowa are inthe front line, the 84th Illinois and 36th Indiana in thesecond line. We drive a whole brigade and they rally on another brigade ofCheatham’s division. Hooker comes forward and says, “Don’t stand and quarrel withthem; go for them!” And they did go with the bayonet.

In the meantime, Osterhaus has pressedis front around [page indistinct] and nearly a whole brigade surrender andagain no enemy confronts us. Our cheers ring over hill and dale. Our loss islight- 2 killed, 4-5 mortally wounded, with some 12-15 slightly wounded. TheRebels left 28 dead on the field and over 30 wounded. We slept on the field butthe roar of battle far to our left did not cease till midnight.

Reveille was at early dawn on November26. All was quiet and the sun rose with a red glare through the smoke of thebattle and camps. It is a day set apart for Thanksgiving, but a day of sorrowto many it really is. But we here do feel truly thankful for victory althoughit takes valuable lives to win it. Our form of government is worth fighting forand must be preserved for posterity. We moved forward towards Ringgold at 9 butwere much delayed by bad roads and destroyed bridges. At 11 we fall in with theenemy’s rear guards and had a warm skirmish, capturing 4 pieces of artillery,10 wagons, caissons, etc. We went into bivouac in line at 1 a.m.

Scattering shots all night preventedsleep and we had reveille at 4 a.m. on November 27. Moving out at dawn, wefound broken caissons, wagons, cartridge boxes, guns, etc. along the road. Ouradvance met the enemy one mile from Ringgold at 9 a.m. and skirmished throughthe town. We saw their lines in a strong position on a hill called Taylor’sRidge. It was Cleburne’s division and one brigade of Walker’s.

Tattered colors of the 84th Illinois

Tattered colors of the 84th IllinoisWe drove in their skirmishers but we were suffering, theyhaving us at a disadvantage. At 12 noon, our artillery came up on the run and tookposition. Generals Grant, Hooker, Palmer, Osterhaus, Geary, and others are atthe head of our column. The 14th Corps is pressing in towards theirrear and flank; the 12th Corps on the other flank. The Rebelsdiscovered the move and lit out on the double quick and saved their bacon bydestroying the railroad bridges. Our loss was 37 killed and about 100 wounded;the Rebels left 26 dead on the field and 60 wounded in our hands, taking manywith them. [To learn more about the fighting at Ringgold Gap, please check outthese posts: “Its Glory Seemed to Have Parted-The 7th Ohio atRinggold,” “No Valor Could Have Rescued Them: The 76th Ohio LosesIts Regimental Colors at Ringgold Gap,” and “."]

During the skirmishing, one woman called to the Rebels tostand their ground, calling our men “sons of bitches” and other names. Herhouse was fired and her husband found killed in the Rebel skirmish line. Wetook a vast amount of forage, corn, flour, meals, etc., there being two millsat that place. They were selling meal at 50 cents per pound in Rebel money. Wetook the engines to Chattanooga; we also took about 500 prisoners, many of themcoming in voluntarily.

November 28th was rainy and cold. We made areconnaissance and found the Rebels were destroying the railroad; we came backand destroyed one mile to help them. The next day we found the ground frozenand it thawed but little through the day. We laid in camp all day. On November30, we marched out at 3:30 p.m., taking the road to the Chickamaugabattlefield. We arrived at Reed’s Bridge (destroyed by Wilder on September 18)at dark and bivouacked for the night. [Click here to visit my Battle of Chickamauga page which features dozens of posts about the bloodiest battlefought in the western theater.]

On December 1, we marched at sunrise and by 10 a.m. foundourselves where the extreme left of the Rebel army lay on the morning ofSeptember 19th, that day long to be remembered by Americans whereour small army was torn, mangled, and overpowered by an overwhelming force, butnot whipped. We passed up the road towards Chattanooga, over ground familiar tothe eye, heart, and mind.

At 11 a.m. we halted and sent details to all parts of thefield to bury the killed of the battle of 70 days before. We found many of ourmen just as they had fallen, save the flesh and any little valuables they mayhave had. Some were covered with leaves and a little dirt, but none wereentirely covered. Their own dead were well buried and many of them there were,too, where the fighting was heaviest on Sunday the 20th.

Many of the trees were entirely cleared of bark by musketry,canister, shrapnel, and much timber felled by heavier metal, some trees aslarge as 22 inches through being cut down. The ladies of the state of Georgiahave had a picnic on the field. It must have been a grand affair with theghastly skulls of their countrymen staring at them and how many of their ownflesh and blood were under that same sod. The women are the worst half of the rebellion.Many of our men's heads were cut off and their own correspondent to the Mobilepapers says they were set up on stumps and logs. But enough of the field. Weleft the sickening scene at 3 and came back through Rossville on theChattanooga road and went into camp at dark.

Source:

Letter fromFirst Lieutenant Lewis Nelson Mitchell, Co. A, 84th Illinois VolunteerInfantry, Monmouth Atlas (Illinois), December 25, 1863, pg. 1

August 24, 2025

Rain Falling Fast and Mud Deep: A Tullahoma Campaign Journal

Sergeant French Brownlee of the 36th Illinois never explains how he kept his journal during the rain-soaked Tullahoma Campaign in June-July 1863, but one gets the sense of the ebullient spirits of his regiment in the midst of a miserably uncomfortable march.

On June 27th, the regiment marched about 20 miles "but were kept on our feet for 15 hours. Part of the time, the sun shone hot and others the rain fell in copious showers. We camped for the night in an orchard. The 36th boys came into camp singing “We are going home to die no more.” A few days later while crossing the a ford of the Elk River, Brownlee observed "the current was rapid with water to the armpits with cartridge boxes on the end of our rifles. The boys halloed and shouted “This is all for the old flag.”

Sergeant Brownlee’s journal entriesconcerning the Tullahoma campaign first saw publication in the July 31, 1863,edition of the Monmouth Atlas published in Monmouth, Illinois. Duringthis campaign, the 36th Illinois formed part of the First Brigade (GeneralWilliam H. Lytle) of General Phil Sheridan’s division of the 20th ArmyCorps. Sergeant Brownlee would not survive the war, succumbing to disease atChattanooga, Tennessee Christmas Day, 1863.

The constant rainy weather was a key element that marked the Tullahoma Campaign and no doubt it proved a miserable experience for the soldiers of both armies who waged war in the midst of it. Federal soldiers often would use their rubber gum blanket as a rain poncho as Si and Shorty are doing in the image above. However, their boots would become saturated and the damp would soon get to their feet, making each step a painful exercise. Drying one's socks at the end of the day was an important part of soldiers taking care of themselves.

The constant rainy weather was a key element that marked the Tullahoma Campaign and no doubt it proved a miserable experience for the soldiers of both armies who waged war in the midst of it. Federal soldiers often would use their rubber gum blanket as a rain poncho as Si and Shorty are doing in the image above. However, their boots would become saturated and the damp would soon get to their feet, making each step a painful exercise. Drying one's socks at the end of the day was an important part of soldiers taking care of themselves. Our division marched on the 24thof June, a portion of our part of labor in the forward movement of the Army ofthe Cumberland. We took the Shelbyville Pike, at first dusty, but soon theheavy rain converted the dust into mud. Marching seven miles, we halted inclose proximity to heavy skirmishing and an artillery duel between Granger’scorps on our sides and the Confeds at Liberty Gap. Being rear guards, we took nopart in the affair. But after remaining a few hours, we filed left and pursuedour march for the Manchester Pike, the rain falling fast and the mud increasingin depth. We camped in a wet bottom, using pine twigs to keep out of the mud duringour slumbers and cedar rails for fuel.

June25: We remainedat the same place, Brannan’s division passing amidst a very heavy rain.

June26: Resuming ourmarch this morning with the rain pouring down in torrents, we marched threemiles and had a pretty hillside for a camp and straw to sleep on.

June27: Our march was resumed early in the morning,but such roads! Wagons fast in the mud, wagons upset, roads blocked. Theinfantry marched as we had done on the previous days, through fields, yards,and gardens without regard to persons. Five miles brought us to the ManchesterPike. Here we got in sight of the pontoon train and were admonished that “bigthings were on hand.” Two or three miles brought us to Hoover’s Gap, a strongposition. We were greatly surprised that the Rebs made such slight resistancewhere the natural advantages were so great.

Filing right during a heavy rain, weleft the pike, taking a dirt road for purposes to us unknown. This afternoon,for the first time in Tennessee, a lady cheered by waving her handkerchief aswe marched by, one of my comrades remarking “You protect my property and I willshake the flag.”

We arrived at Fairfield in theafternoon [Page is indistinct] a skirmish took place here, the second brigade ofour division participating. The 36th Illinois loaded at will and byfiling left was thrown in the advance with the right company deployed asskirmishers, but nary a gun was fired and nary a Reb spied.

Resuming our march, we passed throughthe first clover field we had noticed in Tennessee, filled with swine, horses,and cattle proving conclusively that the country is adapted to clover. This day’slabor was severe, many soldiers falling out of the ranks through fatigue. Wemarched 18-20 miles but were kept on our feet for 15 hours. Part of the time,the sun shone hot and others the rain fell in copious showers. We camped forthe night in an orchard. The 36th boys came into camp singing “Weare going home to die no more.” But why recite our marches to the conservatives?Not a dollar of their money can we get of their money to assist in relievingour sick and wounded soldiers.

I noticed two ladies crying thisafternoon as we marched along the road and supposed they had lost or relativeor friend. But the next morning I ascertained it was only a couple of horses. Isuppose these ladies approximate the feelings and opinions of Northernconservatives who have no tears to shed for their distracted country.

Colonel Nicholas Greusel, 36th Illinois

Colonel Nicholas Greusel, 36th Illinois

June28: A march ofseven miles brought is to Manchester, rain falling fast, mud deep, the roadsalmost impassable. We crossed two branches of the Duck River, the smallestbranch spanned by a bridge 210 feet in length. Two companies of Rebels had beenleft to guard and destroy these bridges, but by a flank movement, thesecompanies were taken in out of the wet and the bridges saved. Manchester is thecounty seat of Coffee County, containing an old courthouse, a great manydecayed buildings, with but few neat residences. Our division, from this place,occupied the advance.

June 29: Leaving amidst the heaviest rain,continuing the greater part of the afternoon, we marched seven miles and campedin a dense piece of timber. In the evening there was sharp firing by thepickets and the 36th took a position on the picket line.

June30: The last ofJune we lay in camp. Our thoughts went back to the Stones River engagement. Thefact that six months ago today the regiment lost 45 killed and 163 wounded. Onthat fatal morning [Page indistinct] sincere Christian and honest citizen,Sergeant McClung fell, a sacrifice to his country. We were sad. Tullahoma theenemy may hold but seven miles from us and the solemn thought that some of ournumber will fall and who or how many is known only to God reverted through ourminds.

We thought of a letter that a youngsergeant of Co. C received shortly after the Stones River battle from aresident favoring a disgraceful peace and calling the soldiers home, givingthat sergeant no encouragement for supping on grapeshot the evening of the 30thstanding by the side of a tree for six hours on picket as a rest through thenight; breakfasting on Minie balls administered by a brigade of Rebels on the31st of December 1862.

But while we were musing thus, we rememberedthat our patriotic governor, the soldier’s friend, had prorogued therepresentatives of this class of citizens just as they were meditatingmischievous things in their minds. All honor to the gallant Yates.

Orderly Sgt. Orison Smith

Orderly Sgt. Orison SmithCo. E, 36th Illinois

July1: About 11 o’clock,we received orders to march. We had proceeded but a short distance when we receivedintelligence that Tullahoma was evacuated. The day was hot and sultry, the roadnarrow, timber on each side. The rays of the sun were piercing. We were alldeceived in Tullahoma. The fortifications were strong- more rifle pits than weexpected to see and hundreds of acres of timber felled to obstruct our advance.We were much surprised to find such a small place and poor site. The onlyredeemable feature was a fine spring of water and a nice creek to bathe in.

July2: Reveille at 3in the morning. We soon started in pursuit of Bragg but were brought to a haltat Elk River, the bridge being burnt. Filing left, we took a meandering routethree miles out of the way, crossing at a shallow ford by wading. The currentwas rapid with water to the armpits with cartridge boxes on the end of ourrifles. The boys halloed and shouted “This is all for the old flag.” We all gotover safe. Our regiment was on picket, our company deployed as skirmishers, butno enemy was discovered. Having been put on half rations, many of the boys hadnothing to eat.

July 3: Theday found us early on the march in pursuit of the retreating foe. Five miles broughtus in view of Winchester and the enemy in line of battle. One company of the 21stMichigan and our company were deployed as skirmishers. We deployed through oneof the largest dewberry patches I ever viewed. The boys were hungry; the berrieslarge and thick, delicious, and tempting. But there is a prospect for Minieballs being hurled at us. [Page indistinct] merely imitating the off side ox inthe prairie team, bend down without stopping, and get some of the largestberries.

Fearing our skirmish line, the Rebelsmade a hasty retreat, thus causing us to lose a shot at the Rebs and thedewberries. Crossing a large stream, we soon took possession of Winchester at a“right shoulder shift, arms.” This is a pretty place. One of the ladiesremarked as we passed through town, “Oh, the poor Confederate troops, how theywill suffer!” We made a short halt- the rain falling fast, but soon resumed ourmarch. The Rebels made a stand a short distance from town on the banks of alarge creek. But we soon dislodged them and a few of the 39thIndiana were wounded.

Plunging through the stream andascending the banks, a painful sight presented itself to our view. A boy of 16had been shot by one of our sharpshooters of the 21st Michigan at adistance of 600 yards. The parents were Union people. The aged mother exclaimedwith tears running down her cheeks, “My son was always in for the Union. Hislast words were ‘hurrah for the Union!” Pursuing our way, we arrived at Cowan’sStation and camped on the ground occupied by Bragg’s forces in the forenoon.Bragg, by burning bridges and felling timber in connection with the heavyrains, made further pursuit for the present impractical.

The health of the boys is good. Ourcompany left Murfreesboro with 43 and of these, all but one are fit for duty. Wehave been down the railroad to Anderson’s Station 15 miles distant. Therailroad is but little damaged. I had the pleasure of performing picket dutyone night in Alabama. The mosquitoes made free use of their bills for the firsttime during my enlistment.

Source:

Campaigndiary from Orderly Sergeant French Brownlee, Co. B, 36th IllinoisVolunteer Infantry, Monmouth Atlas (Illinois), July 31, 1863, pg. 2

August 23, 2025

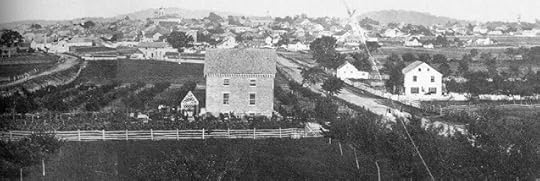

War is a Fearful Business: A Civilian Recalls Gettysburg

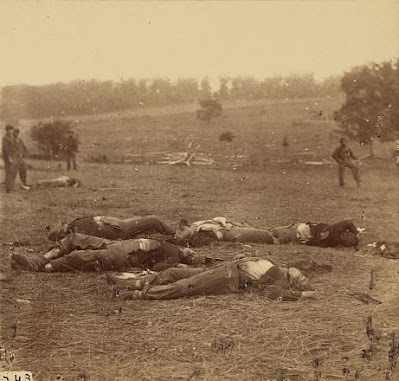

Dr. Andrew J. Traver of Andersontown, Pennsylvania lived a mere 300 yards from the advance of Jeb Stuart's cavalry in the days before the Battle of Gettysburg. In this extraordinary letter written 9 days after the battle, he describes to friends in Illinois the carnage left in the wake of the costliest battle of the Civil War.

"Over thousands of acres and for miles the ground was covered with dead and dying," he noted. "Broken cannons and caissons, rifles, muskets, knapsacks, cartridge boxes, blankets, hats, caps, boots, shoes, canteens, beef, crackers, and cooking utensils, dead horses, broken ambulance wagons, ammunition wagons, etc., all mixed and mingled in one mass of ruin. In many places the ground was covered with blood and water shoe deep and along the sloughs, the blood and water ran in streams."

"I returned home on Friday [July 10], one week after the battle, and some portions of the field were yet covered with dead Rebels who had not been buried," he continued. "The Rebel prisoners were sent out to bury them but the smell was beyond endurance. Decomposition was so rapid that they would fall to pieces on handling. Hundreds of them were strewn on piles and a little dirt thrown on them. Others were piled in between rocks and thrown in gutters and runs with stones and brush thrown over them with their heads, arms, and legs sticking out."

Dr. Traver’s letter first sawpublication in the July 24, 1863, edition of the Monmouth Atlaspublished in Monmouth, Illinois.

Andersontown,Pennsylvania

July 12,1863

Dearfriends,

After passing through one of the mostexciting and fearful periods of my life, I embrace a few moments of leisure inorder to drop you a few lines concerning matters and things in our locality asregards the great Rebel raid, the desperate fighting, etc. You have had fullparticulars through the press but of the awful realities you know but little.

We have lived one whole week under theadministration of Jeff Davis and from such another week I hope the good Lordmay forever deliver us. The Rebels have ransacked almost every hill and valleysouth of the Susquehanna River and carried off horses, mules, cattle, sheep,wheat, and flour. They have destroyed grain and grass fields, burned fences andbridges, plundered houses, and robbed private citizens of their money andclothes. In many instances they have destroyed women’s clothing and broke theirdishes, destroyed their bed clothes, and in fact, demolished everything exceptwhat they had on their persons. This I have seen with my own eyes and knowwhereof I speak.

This was the case when they first cameinto the neighborhood, but when they found they had to leave, they becamedesperate. Many farmers were entirely ruined. Andersontown was lucky. Stuart’sand Fitzhugh Lee’s Rebel cavalry, 15,000 strong, passed close by us. Theiradvance was up the road about 300 yards from our house. They were making forthe Cumberland Valley to join General Jenkins’ guerillas, but our militia from Harrisburghad driven him up beyond Carlisle and the Rebels hearing our cannons roaring upthe valley and thinking they were cut off, made a hasty retreat to Gettysburg.They burnt many of their baggage wagons in the passes of Round Top Mountain, soyou see how we were saved.

Jenkins’ guerillas were in Lisburn andSiddensburg, but our cavalry from New Cumberland under Colonel Wynkoop were soclose upon them that they had but little time to plunder the country except tosteal horses. The copperheads suffered dreadfully as they did not hide theirhorses. They boasted before the Rebels came that their property would berespected and no Knight of the Golden Circle would be molested. But the poor,deluded creatures were dreadfully disappointed.

I was in Harrisburg for three daysunder arms but I had to fight for nothing and board myself, [page is indistinct].Would go home and act as bushwhackers as Harrisburg was amply defended. I wasas far as Gettysburg and here, oh my God, I hardly know how to describe theawful carnage. Such desperate fighting I suppose had never been known upon the Americancontinent. The Rebels knew that the Confederacy was suspended upon theiractions and the Union army was determined to drive them from our soil, orcapture and kill them at all hazards and this they succeeded in doing to agreat extent.

It will never be known how many Rebelswere killed as hundreds were scattered through the rocks and mountains thatwill never be taken any account of. I returned home on Friday [July 10], oneweek after the battle, and some portions of the field were yet covered withdead Rebels who had not been buried. The Rebel prisoners were sent out to burythem but the smell was beyond endurance. Decomposition was so rapid that theywould fall to pieces on handling. Hundreds of them were strewn on piles and alittle dirt thrown on them. Others were piled in between rocks and thrown ingutters and runs with stones and brush thrown over them with their heads, arms,and legs sticking out. This the Rebels done themselves; as far as our soldiersburied them, they did it with more decency.

But the Rebels appeared to have no respectfor themselves or anybody else. They were so completely thrashed and outwittedat every point that they appear to have given up in despair. Over thousands ofacres and for miles the ground was covered with dead and dying. Broken cannonsand caissons, rifles, muskets, knapsacks, cartridge boxes, blankets, hats,caps, boots, shoes, canteens, beef, crackers, and cooking utensils, deadhorses, broken ambulance wagons, ammunition wagons, etc., all mixed and mingledin one mass of ruin. In many places the ground was covered with blood and watershoe deep and along the sloughs, the blood and water ran in streams.

From my own personal observation, I amconvinced that the Rebels lost two killed to our one on our center and left,and on our right, they lost three to our one. In fact, one what is calledSugarloaf Mountain and along Rocky Creek, I could not find more than 20 of ourmen killed whilst that of the Rebels was from 800-1,000. Our men had piled uprocks into breastworks and the Rebels became frantic at their loss and chargedour works four different times under Longstreet, leaving their dead three orfour men deep in front of our lines. A little farther to the right, thePennsylvania Bucktails charged on Longstreet’s corps and captured one wholedivision.

On the afternoon of the 3rd,General Lee sent a flag of truce asking permission to bury their dead, but thisgame would not work. General Meade was not to be caught with their chaff andsent word back that the dead did not need much attention and that he intendedto fight awhile yet. The Rebels soon after commenced to retreat in disorder,throwing down their guns in utter despair. Many thousands were captured andhundreds fled to the mountains and deserted. Their loss in killed, wounded,prisoners, and deserters will not fall much short of 40,000.

I conversed with many Rebels whoadmitted that Lee brought 120,000 infantry, 20 artillery regiments, and 60,000cavalry over the Potomac, making in round numbers 200,000 men, about 140,000were engaged at Gettysburg. [Dr. Traver’s estimate is off by about a factor oftwo!] The rest were posted at different points between here and Williamsport toguard communications, etc. General Meade has about 150,000 men, but one granddivision did not arrive so that we had scarcely 100,000 men on the field andonly about 75,000 engaged, the rest being held in reserve for any emergencythat might arise.

The balance of Lee’s army had made its way to Hagerstown,hotly pursued by our cavalry who captured a great portion of their baggagetrains and stolen horses. Our cavalry have also destroyed the pontoons over thePotomac. Lee’s army is in a bad fix. Yesterday, heavy cannonading was heard andI suppose another battle was fought on the banks of the Potomac but I have notyet heard the result. For six days, the earth shook from the Potomac to theSusquehanna beneath the heavy firing of artillery. Hanover Junction, Hanover,Carlisle, and Gettysburg were the principal places of conflict.

It has been raining nearly every day since the fighting commencedand I fear that what grain and grass the Rebels left will be spoiled.Everything was neglected during the conflict. What horses were not taken by theRebels were over the river and the grain has been left to rot in the fields.Many of the farmers will not have a bushel of grain or forkful of hay, thearmies having pastured and eaten everything. Truly, war is a fearful business.

But I begin to hope that the rebellion will soon be wound upas the Rebels are beginning to lose confidence in themselves. I talked with avery intelligent officer of the Rebel army who admitted their cause was lost asthey had raised their last army. The whole South was recruited to gather up Lee’sgreat army for the march to Pennsylvania. Their object was to whip our army atGettysburg and then divide into three divisions: one for Washington, one forBaltimore, and one for Harrisburg. By this means, they calculated to counteractthe loss of Vicksburg and the Mississippi Valley which they knew was lost tothem. But they have failed and I think their cause is about lost.

A.J. Traver

To read someother civilian accounts of the Gettysburg campaign, please check out theseposts:

A Civilian's Viewpoint of Lee's Invasion of Pennsylvania

With the U.S. Christian Commission at Gettysburg

On Soil Enriched with Their Blood: The Aftermath of Gettysburg

Dedicating the Gettysburg National Cemetery

Source:

“Letter fromPennsylvania,” account of Dr. Andrew Jackson Traver, Monmouth Atlas (Illinois),July 24, 1863, pg. 2

August 15, 2025

With the 11th Ohio Cavalry in the Far West

Among Ohio’sregiments during the Civil War, none traveled further west than the 11thOhio Volunteer Cavalry. While most of their Buckeye trooper brethren servedeast of the Mississippi River, the 11th Ohio (and for a portion of thewar the storied 2nd Ohio Cavalry) served in the western territories.Rather than fighting the Confederacy, the 11th Ohio Cavalry servedto buttress the Federal military presence along the Oregon Trail and at otherpoints protecting the flow of emigrants who sought their fortunes in the FarWest.

“To be sure, we are not engaged in asactive service as those in the armies in the east or southwest, yet at the sametime, we are in the service of the U.S. and the position we occupy is of farmore importance as that of any troops in the field,” one trooper stated. “Thesewestern forts have to be garrisoned by some troops, and why not us?”

Fort Laramie in Idaho Territory in 1864 as depicted by Lieutenant Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio Cavalry. Collins would be killed in a skirmish with Indians the following year.

Fort Laramie in Idaho Territory in 1864 as depicted by Lieutenant Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio Cavalry. Collins would be killed in a skirmish with Indians the following year. (PBS Antiques Roadshow)

Gold served as a primary lure drawingemigrants to the West and as Hospital Steward Kilburn H. Stone noted whilestationed at Fort Laramie in the newly created Idaho Territory (now present-dayWyoming), “it is estimated that no less than 20,000 emigrated between themonths of May and August 1863, a large portion of which passed by this fort. Goldwas first discovered in the Salmon River in 1861 and caused a large emigrationto this country. In 1862, gold was discovered in quantity on the KooskooskiaRiver and its mines are now considered among the richest in the west. Gold isfound in the bed and along the banks of these rivers. The Bannock city goldmine fever raged very high here now. The citizens, discharged soldiers, andmountaineers are nearly all going or making calculations to go just as soon as springopens.”

“A large increase of emigration isexpected in the spring,” he continued. “This country abounds plentifully in allkinds of wild game such as buffalo, black and grizzly bears, elk, deer,antelope, wolves by the thousands, hare, and rabbits. There are now about 500men stationed at this garrison; the balance of the regiment are stationed alongthe old stage line, some at Fort Halleck, some at Sweetwater Bridge, and someat South Pass; they are stationed for the purpose of keeping the Indians atbay.”

“Theoccasional severity of the weather is worthy of record. On the 3rd,4th, and 5th of January 1864, the mercury at Fort Laramiefroze each night- on the 3rd for four hours, on the 4thfor 15 hours, and on the 5th for 12 hours. A spirit thermometerwould have indicated from 50-60 degrees below zero. On one of these mornings anexperiment was made with sanitary whiskey and upon being exposed in a tin cup,it froze solid in 20 minutes and was tossed about like a brickbat.” ~ WhitelawReid, Ohio in the War

Writing from Fort Laramie in December 1863, one trooper ofCo. D noted “we are in almost perfect safety” and “are in a health country,have plenty of everything, and dress parades every evening if the inclemency ofthe weather is not too much so. We certainly should be the most happy andcontented soldiers in the U.S. service, especially since we have a Reading Room(which is a good institution), and a brass band. Yes, strange as it may seem,we have a brass band 600 miles from civilization proper. Co. A organized theband, procured instruments, sent to Denver for a teacher, and we now have themost inspiring strains of music ever heard in Idaho I reckon.”

The far west showing the initial outlines of the Idaho Territory. This entire region was the theater of action for the 11th Ohio Cavalry during the Civil War.

The far west showing the initial outlines of the Idaho Territory. This entire region was the theater of action for the 11th Ohio Cavalry during the Civil War. Regarding the reading room, Whitelaw Reid added that “alibrary of 800 volumes was obtained from the states by donation and purchase anda reading room established at headquarters which was well filled withnewspapers and magazines. All books and newspapers were distributed to distantposts and were exchanged from time to time. Even a theater was improvised andthough pantomime was cultivated principally, tragedy and comedy were notneglected and in fact were not badly presented.”

Thinking of music, Hospital Steward Stonenoted how in February 1864 a tribe of Sioux visited Fort Laramie and performeda “war dance” as he called it. “When they entered the parade ground they camerunning as fast as possible, whooping and yelling as the top of their voices inthe most hideous manner imaginable,” he wrote. “They then formed a circle, maleand female, old young, and took their respective positions in the circle.Directly the musicians began and then away they went, all hands round, singing,whooping, and yelling again tremendously.”

“There were about 150 part who tookpart in the mazey dance while hundreds of other Indians were on-lookers,” Stonecontinued. “Most of the females (or squaws as they call them here) were attiredin beautiful, beaded deer skin dresses of their own industry and neatness.Their music consisted of four drums, made more like a banjo than anything I canthink of. They also had some powder horns filled with small pebbles that theyrattled and called music. I see any quantity of Indians every day; they are themost of them very friendly. I often go to their wigwams and smoke with them thepipe of peace. They have not been troublesome at all of late.”