Daniel A. Masters's Blog, page 4

June 28, 2025

Cleaned Out at Sabine Crossroads

After waiting all afternoon to go into action at Sabine Crossroads, Dan Dickinson and the 2nd Massachusetts Light Artillery were quickly overwhelmed once the action began.

"At every discharge, terrible gateways were made in their ranks and the shells we plunged into their midst scattered death and destruction far and wide," he wrote. "Their bullets swept the hill upon which we were posted in perfect showers but happily they aimed too low and none on our piece were killed, though two men were mortally wounded and eight of ten cannoneers were wounded. I am one of the lucky two who were not wounded though how I escaped is a miracle and a great wonder to me. One ball went through my pants at the knee, another struck my belt but did not penetrate. We brought our limber forward when there was no longer any hope of support or succor coming to aid us, limbering our gun when the Rebels were only 75 feet or so from our cannon. Five of the six horses attached to the limber were shot dead and the other was badly wounded. We were ordered to retreat and as there was no hope of bringing off our piece, we left going down the hill while the enemy with oaths yelled surrender."

Dan Dickinson’s account of his batterybeing overrun at the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, written to his father inWaukegan, Illinois, first appeared on page one of the May 21, 1864, edition ofthe Waukegan Weekly Gazette.

The 2nd Massachusetts Light Battery under Captain Ormand F. Nims lost all six of its guns, 82 horses, and 24 casualties at Sabine Crossroads.

The 2nd Massachusetts Light Battery under Captain Ormand F. Nims lost all six of its guns, 82 horses, and 24 casualties at Sabine Crossroads. Grand Ecore,Louisiana

April 16,1864

My dearfather,

We have had a great battle. On theafternoon of Thursday April 7th our battery was ordered to the frontas skirmishing was going on. We galloped through the village of Pleasant Hilland again entered the pine woods. We were unable to get into position owing tothe woods being very thick and dense and we were ordered back. We were alldisappointed for since leaving Alexandria our cavalry had been constantlyskirmishing and we had not be able to get into any of it. But little we thoughtthat speedily Nim’s battery would see a hard day…

On Friday morning the 8thwe started at 6 o’clock. The Rebels made a very obstinate stand at a mill creeksix miles from Pleasant Hill but were driven out before our battery came up. Atthis place, my section (the left) halted while the right and center sectionswent on under the command of Second Lieutenant [Joseph W.] Greenleaf. These sectionsrepulsed a charge of the enemy about 1 o’clock before we came up. Our sectionmarched slowly and easily along, arriving at the position of the rest of ourbattery at about 2:30 in the afternoon. We went into battery and as the timehad come to open action, some threw themselves on the ground and went to sleepwhile other reclined against the pines, passing the time in conversation.

At 3:30, orders came for us to openthe ball. On our right in the woods we heard heavy skirmishing which slowlyapproached near to us. We directed our piece to the right and our infantryentered the woods on the right. In the short space of 10 minutes, beingoutflanked and driven round to the center, our infantry reappeared right beforeout battery not more than 200 feet from us, followed by an overwhelming forceof drunken, yelling Rebels. They halted before us for a minute, poured aterrible, withering volley into the enemy, then came back towards the artilleryin a crouching run and passed by us, going down the hill and across the fieldas fast as they possibly could.

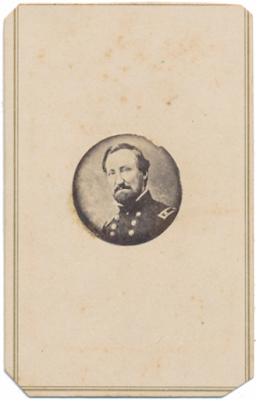

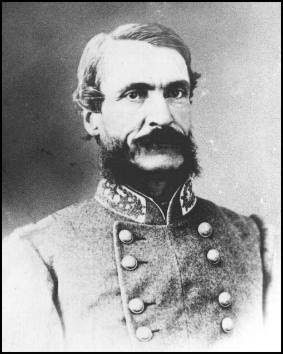

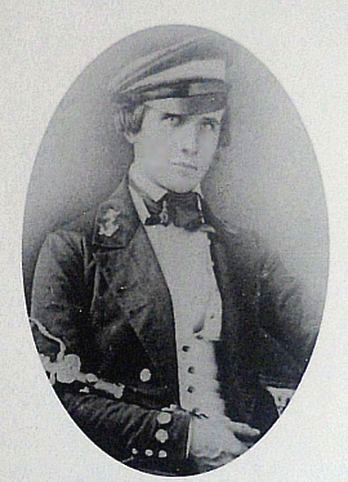

Captain Ormand F. Nims

Captain Ormand F. Nims2nd Massachusetts Light Artillery

We fired very fast indeed, and theroar of our pieces would not have ceased 10 seconds before it boomed forthagain. I doubt not but that their generals could say like Marshal Lannes “I couldhear the bones crush in my command like glass in a hailstorm.” Rebel prisonerssince captured say that the taking of our battery proved to be the mostterrible work they ever had and if we had had only a small force of infantry tosupport us that they never could have stood such fire. At every discharge,terrible gateways were made in their ranks and the shells we plunged into theirmidst scattered death and destruction far and wide. They only halted once, asif debating upon the expediency of their plan, and no doubt but those inadvance would have been glad to have fallen back. But they were charging infour deep, long columned lines and those in the rear forced those on who werein the advance.

Their bullets swept the hill uponwhich we were posted in perfect showers but happily they aimed too low and noneon our piece were killed, though two men were mortally wounded and eight of tencannoneers were wounded. I am one of the lucky two who were not wounded thoughhow I escaped is a miracle and a great wonder to me. One ball went through mypants at the knee, another struck my belt but did not penetrate. We brought ourlimber forward when there was no longer any hope of support or succor coming toaid us, limbering our gun when the Rebels were only 75 feet or so from ourcannon. Five of the six horses attached to the limber were shot dead and theother was badly wounded. We were ordered to retreat and as there was no hope ofbringing off our piece, we left going down the hill while the enemy with oathsyelled surrender.

I escaped being wounded again bymiracle. There was a man behind who was shot through the brain and nearlystruck me when he fell over. Another on my left was shot through the groin andfell. There was quite a number shot while going down the hill. When I arrivedin the woods on the east, I found the road blocked up with wagons from whichthe mules had been detached filled with infantry and cavalry without officers,officers without men, the utmost confusion reigning on all sides as everyonesought as best he could to save his own life.

Soldiers, panic-stricken, heedless,and paying not the slightest attention to the prayers of officers to rallyagain. The road was jammed, crammed with a demoralized, crowded mass, woundedmen crawling to the rear to be cared for, General Banks and his staff almostpraying the men to form in line. The enemy was close upon us and the shellsshrieking through the air burst on all sides, adding to the terrible panic.

General Nathaniel P. Banks and wife

General Nathaniel P. Banks and wifeAlthough this was the first time I hadbeen under fire, yet I felt perfectly cool throughout and did not feel theleast fear and would have been perfectly willing to have gone into action againif I had known that I should be killed. My companions were perfectly cool andwe all endeavored to rally the troops but in vain. I saw three men cut down forrefusing to halt. Three of our pieces were left on the hill and three that werenot so exposed to the enemy’s fire were brought away from the field and gotinto the woods, but the wagon train completely blocked the road and we wereordered to spike the guns and leave them since it was impossible to get themaway.

The mass retreated in a mannerperfectly terrible and frightful for eight miles. It was nearly dark when webeheld the 19th Corps drawn up before us in a line of battle. It wasthe 13th Corps that retreated so disgracefully and it was the 19thCorps that saved us all from being captured. As the enemy came up, they weremet by a withering volley from the whole corps which lasted for two minutes ormore. The enemy was checked. That day was a reenactment of Bull Run and theenemy captured 22 pieces of artillery. I am not acquainted with the loss on ourside but it must have been heavy in killed and wounded.

That night our army fell back 18 milesto Pleasant Hill and on Saturday [April 9, 1864] the Rebels got worsted.Western troops fought that day under General Smith who drove the enemy sixmiles. All the artillery had been recaptured except one battery which theRebels will keep out of our way since they have been fighting for it for overtwo years. General Sims, the chief of Rebel artillery in this department, senthis regards to Captain Nims yesterday saying that our battery was the best hehad ever seen and that he should take the best of care of it.

To use an expression, I am completelycleaned out of everything. My knapsack containing all my clothing and otherindispensables was strapped to the caisson and was left behind. Please give Mr.Lindsay an order to make me some clothes and send them to me and I will sendhim the money the first pay day. I have nothing but one pair of torn, dirty,ragged pants, one shirt, a suit of underclothes, and a torn, dirty blouse, nostockings, no change of clothing, no paper, no money, no postage stamps.

As for our battery, it is rumored thatwe go to New Orleans to refit and reorganize. I hope so. General Lee was on thetop of the hill during the fight and is, in my opinion, a very brave man. Whenwe were ordered to leave our pieces, I noticed him on his horse perfectlycomposed amid a terrible shower of bullets. Porter Scott conducted himself in avery courageous and gallant manner and is worthy the name of a brave man.

Goodbye and may God protect andprosper you is the prayer of your affectionate son, D.O. Dickenson, Jr. Don’tforget my clothes.

To learn more about the Red River campaign and the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, please check out the following posts:

Worse Than Madness for Us: The 56th Ohio at Sabine CrossroadsEvery Man for His Own Pork & Beans: The 29th Wisconsin at MansfieldCursing Banks and Franklin: With the 77th Illinois at Sabine CrossroadsSource:

Letter fromPrivate Daniel O. Dickinson, Jr., 2nd Massachusetts Light Artillery, WaukeganWeekly Gazette (Illinois), May 21, 1864, pg. 1

June 27, 2025

Taking Fort Morgan in Mobile Bay

Nearly threeweeks after the Battle of Mobile Bay, Lieutenant Edward N. Kellogg of the U.S.Navy stood outside Fort Morgan as part of the contingent of Federal officerschosen to accept the surrender of Fort Morgan. It proved an impressiveceremony.

"At 2 o’clock that afternoon most of the naval and armyofficers landed at the fort to witness the raising of the old flag over thestronghold that has kept us so long at bay,” he wrote. “The Rebel troops, 560in number, were marched out and stacked arms, and equal number of our own marcheddown in front of the line, the band playing “Hail Columbia,” the “Star-SpangledBanner,” and “Yankee Doodle” among other patriotic airs till they were abreastwhen they halted and faced the graybacks at a distance of ten feet. TheAmerican colors were now run up on the flagstaff and the Rebel flag hauleddown. The band again struck up, the whole fleet fired a salute, the vessels insuccession according to rank and a battery of two field pieces on shore contributingto the grand chorus. In the meantime, “Old Page,” who had turned his back asthe band passed, came between the lines of soldiers where the officers were mostlyassembled and surrendered his flag, fort, garrison, and everything thereuntobelonging unconditionally.”

Lieutenant Kellogg’s letter describing the surrender of FortMorgan first saw publication in the September 10, 1864, edition of the WaukeganWeekly Gazette.

The smoke-stained ruins of Fort Morgan show the impact of Federal shelling in this image taken shortly after the fort's surrender in August 1864. After touring the fort, Lieutenant Kellogg described the fort's interior was "one mass of rubbish." The fleet threw more than 3,000 shells into the fort on August 22nd and the resulting fire threatened to ignite the powder magazine. Confederates rolled the powder drums into a cistern to prevent their detonation but without powder were essentially rendered defenseless.

The smoke-stained ruins of Fort Morgan show the impact of Federal shelling in this image taken shortly after the fort's surrender in August 1864. After touring the fort, Lieutenant Kellogg described the fort's interior was "one mass of rubbish." The fleet threw more than 3,000 shells into the fort on August 22nd and the resulting fire threatened to ignite the powder magazine. Confederates rolled the powder drums into a cistern to prevent their detonation but without powder were essentially rendered defenseless.

U.S. Steamsloop Oneida, Mobile Bay, Alabama

August 24,1864

Victory once more perches upon thebanner of freedom and the Mobile blockade is now classed among the things thatwere. Day before yesterday the fleet and shore batteries opened the bombardmentand kept it up all through the day. The monitors and double-enders only of thefleet firing during the day. At dark, the citadel inside the fort was seen tobe on fire and the firing was kept up with greater spirit than during the day.Our fire was so hot the Rebel garrison could not fire a gun during part of thebombardment but kept safely sheltered in their casemates. The sharpshooters onshore were so near the fort that it was certain death for a Rebel to show hishead above the parapet. Our fire completely enfiladed the fort as the insideand outside fleet and shore batteries played on all parts simultaneously, everypart being exposed to a murderous fire.

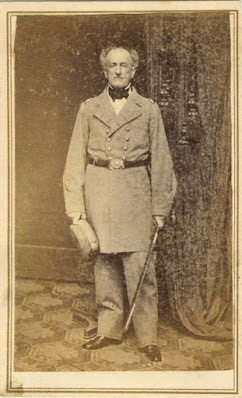

Brigadier General Richard L. Page

Brigadier General Richard L. Page"Ramrod Page"

Yesterday morning at daylight a whiteflag was hoisted on the parapet of Fort Morgan and the firing ceased. A smallboat with a flag of truce was soon seen putting out for the flagship butGeneral Gordon Granger who was on a small steamer in the bay, interrupted itand brought it alongside his own vessel. The officer of the boat was the bearerof a dispatch from “Ramrod Page,” as he was familiarly nicknamed in our army previousto his turning traitor, proposing terms of surrender.

At 2 o’clock that afternoon most ofthe naval and army officers landed at the fort to witness the raising of theold flag over the stronghold that has kept us so long at bay. The Rebel troops,560 in number, were marched out and stacked arms, and equal number of our ownmarched down in front of the line, the band playing “Hail Columbia,” the “Star-SpangledBanner,” and “Yankee Doodle” among other patriotic airs till they were abreastwhen they halted and faced the graybacks at a distance of ten feet. TheAmerican colors were now run up on the flagstaff and the Rebel flag hauleddown. The band again struck up, the whole fleet fired a salute, the vessels insuccession according to rank and a battery of two field pieces on shore contributingto the grand chorus. In the meantime, “Old Page,” who had turned his back asthe band passed, came between the lines of soldiers where the officers were mostlyassembled and surrendered his flag, fort, garrison, and everything thereuntobelonging unconditionally.

General Gordon Granger

General Gordon GrangerWe now entered the fort and found thatthe 11- and 15-inch shells had effectually done their work. Fifteen guns weredismounted or entirely disabled. The citadel was completely destroyed by beingset afire by our shells and the whole inside of the fort was one mass ofrubbish that was knocked down from the walls. The garrison with enoughprovisions might have held out for months without any loss of life if they hadbeen disposed but it would have been useless for them to have suffered the annoyanceof broken sleep, imprisonment in the casemates, and perhaps sickness among manyother evils with no hope of reinforcements or supplies. If Page could havefired his guns they would probably have held out much longer. There were fourmonths of provisions in the fort and the garrison had been put on reducedrations the day we entered.

The Rebel guns were of English and Rebel make principally:the 7-inch Brooks’ rifle being one of the best guns in the world. It was one ofthese guns that wounded our captain, exploded our boiler, and disabled ourafter 11-inch gun. I was pleased to see the gun with one trunnion knocked offand otherwise disabled. [Please see my previous post “Bones in the Brackets: AGraphic Account of the Battle of Mobile Bay” for further details on the Oneida’sfight on August 5, 1864.]

The capture of Fort Morgan places usin possession of the whole bat as far up as Long River Bar about five milesfrom the city. Some hard fighting will yet have to be done before the citysurrenders but that work will devolve upon the monitors and small gunboats, thelarge ships not being able to get up so far. Thus far, the port is sealed againstblockade running and the large fleet now here will be released from blockadeduty. The city of Mobile can be easily reached by the guns of our fleet as someof our vessels have already been within three miles of the city.

Our ship will leave soon either forPensacola or New Orleans for necessary repairs before proceeding north. Deadbodies are floating by the ship every day, drifting back and forth with thetide. (To read Lieutenant Kellogg's account of the Battle of Mobile Bay, click here to read "Bones in the Brackets: A Graphic Account of the Battle of Mobile Bay.")

Source:

Letter fromLieutenant Edward Nealley Kellogg, U.S.S. Oneida, Waukegan Weekly Gazette(Illinois), September 10, 1864, pg. 3

June 26, 2025

Bones in the Brackets: A Graphic Account of the Battle of Mobile Bay

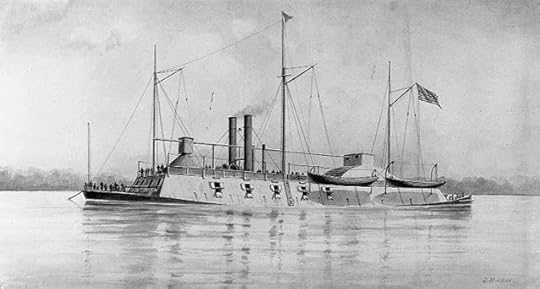

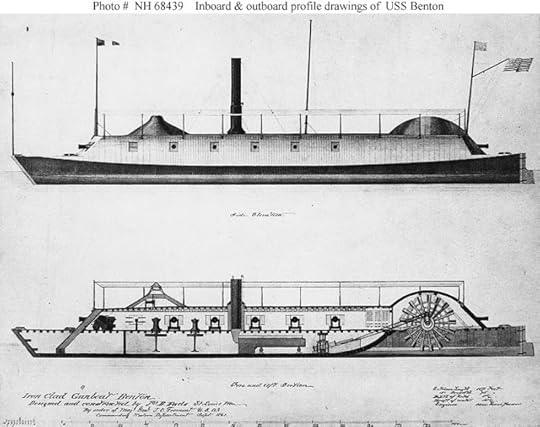

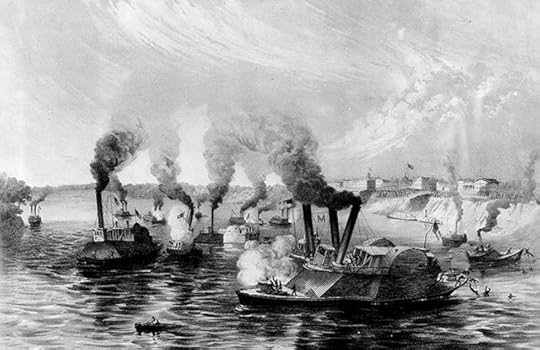

Disabled bya shot that blew her starboard boiler, the U.S. steamer Oneida driftedhelplessly in Mobile Bay as the Rebel ironclad Tennessee slowly steamed aroundher stern then let loose with a devastating broadside.

“Three men were killed in my division and six wounded, but Iescaped unscathed although covered with a shower of splinters and the brains ofmy unfortunate Marine bespattered my face,” Lieutenant Edward N, Kellogg wroteto his father. “Three of our men had their heads shot off and the pieces ofskull bones flying around actually wounded seven or eight men. The shell thattook off the captain’s arm took off the head of a Marine at my 11-inch gun andwounded both captains of the gun as well as the first loader, besides slightlywounded several others by scattering around fragments of bones which are nowburied so deep in the brackets as makes it impossible to get them out but bycutting the wood.”

Lieutenant Kellogg’s letter, written two days after theBattle of Mobile Bay to his father, first saw publication in the September 3,1864, edition of the Waukegan Weekly Gazette.

A total of seven sailors and one marine aboard the Oneida were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroism at Mobile Bay. "All of our men behaved nobly," Lieutenant Kellogg stated.

A total of seven sailors and one marine aboard the Oneida were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroism at Mobile Bay. "All of our men behaved nobly," Lieutenant Kellogg stated. U.S. SteamerOneida, Mobile Bay, Alabama

August 7,1864

Dear father,

The bloody fight is over andadditional luster has been added to the old flag. Our colors were hauled downat sunset on the 5th crowned with victory and glory while many amangled body told too well the trying ordeal through which they had passed. Onthe evening of the 4th, it was announced that the attack would bemade in the morning at 3:30 on the 5th. The vessels with theirconsorts were lashed together and at 5 we headed up the channel, the Oneidawith the Galena lashed to our port side bringing up the rear.

The line was about three miles longwith the Brooklyn leading the van. The Hartford and consort camesecond, Richmond came third, Lackawanna came fourth, Monongahelacame fifth, Ossipee came sixth, and Oneida seventh. About 6:30,Fort Morgan opened fire and was immediately answered by the Brooklyn andHartford and the action soon became general. The ironclads Tecumseh, Manhattan,Chickasaw, and Winnebago formed the inside line abreast of theleading ships. At 7:05, the Oneida opened fire with her forward rifledinch pivots with 15- and 10-inch shells. The orders were that as each ship gotabreast of the fort, they must stop their engines and drift with the floodtideto prevent fouling their propellers.

As we neared the fort, we fired withshorter fuses and opened with the broadside guns as soon as they could be madeto bear. While abreast of the fort we fired 2-1/2-inch shrapnel while the enemyanswered us with the same kind of projectile. We received our first shot, orrather first shell, through the cabin at the waterline which killed the captain’ssteward and made a complete wreck of the furniture and bulkheads and notleaving a piece of board as large as a shingle.

The Rebel ram Tennessee now bore down on us just as ashell from the fort exploded in our starboard boiler and completely disabledus, scalding all our firemen and engineers horribly. A temporary panic nowensued as the men from below rushed on deck with their arms and faces scaldedin a frightful manner. The steam followed them and drove the men from the guns,leaving us helpless. But the Galena was uninjured and towed us slowlyalong. As the steam somewhat cooled the men again rallied and as the Tennesseeapproached, they gave a loud shout of defiance and poured a hot fire intothe ugly-looking Rebel.

Our 11-inch solid shot glanced harmlessly from her mailedsides and she moved silently along. But why don’t she fire, was the question ineveryone’s mouth. Other guns were sending their shot and shell crashing throughus but still she moved mysteriously along. The fact was she had seen theexplosion of our boiler and came down to sink us, but it seemed as thoughProvidence had interfered for her primers all snapped. She soon rounded tounder our stern and now her guns exploded. We lay completely at her mercy whileher 130-pound shells went raking and crashing through us, mangling and woundingour men while they had no chance to return her fire.

The carnage here was awful. Shortly after the explosion, ourbrave and gallant captain J.R. Madison Mullaney had his arm shot off and was carried below.The command now devolved on the executive officer Lieutenant Huntington fromSpringfield, Illinois and nobly did he emulate the example of our bravecaptain. Our men cheered lustily in spite of the officers who, feeling for thewounded on deck and below, tried to check them.

The Monongahela was the first of four Federal vessels that rammed the Tennessee.

The Monongahela was the first of four Federal vessels that rammed the Tennessee. The Tennessee, having got about half a mile astern ofus, again turned, this time bent upon sinking us, but the monitors had beenwatching her and bore down to our assistance. The admiral not knowing we weredisabled, signaled us and several other vessels to run the Tennessee downat full speed, although we had signaled that our captain was wounded and theship disabled. We could do nothing of course but the Itasca came toassist in towing us out of range.

We now intently watched those noble ships as they rushed towardstheir adversary with a full head of steam. The Monongahela bore down uponthe Tennessee at the rate of 10 knots, but striking obliquely, sheslipped and shot past. The Lackawanna now came boiling along and struckher fair, which hulled her over slightly, but she, too, slipped and for aminute the two vessels lay side by side in contact, pouring their deadly fireinto each other. Next came the Hartford who discharged all her shells as shewas advancing and loaded with solid shot. She, too, struck the infernal machineonly to glance off from her slippery side. The monitors in the meantime hadbeen pouring their 11- and 15-inch shot into her which had carried away hersteering apparatus and knocked her smokestack overboard.

A loud cheer went up from the anxious fleet as the volumes ofblack smoke poured from the hole where her smokestack had stood. With her newwheel ropes rigged, she turned and ran for Fort Gaines, but our vessels were inhot pursuit and pressed her closely. The Ossipee, which had got ahead ofthe others, now made a rush to strike her when she perceived a white flagflying from the top of the Rebel. Her engines were immediately reversed, buttoo late to prevent her striking the ram a heavy blow. A boat was sent on boardand the traitor Admiral Buchanan who was lying wounded below surrendered hissword to the fleet.

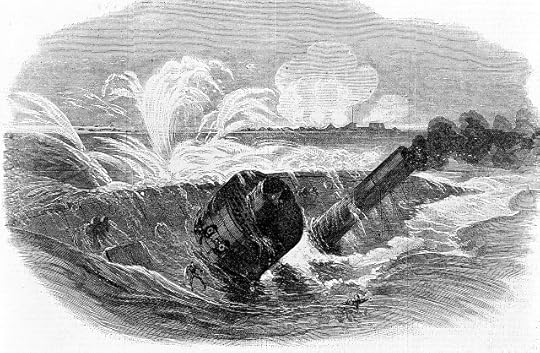

Sinking of the U.S.S. Tecumseh

Sinking of the U.S.S. TecumsehCheer after cheer rang from the throats of our gallant tarsand the fight was over. But while this fight was going on, another scene was beingenacted in another quarter where our attention had not been attracted. Captain [James Edward] Jouett of the Metacomet, seeing the Rebel gunboat Selma makingtracks for Mobile, immediately gave chase and a short but decisive fight endedin the surrender of the Rebel gunboat. The remaining cowardly gunboats tookshelter under the guns of Fort Morgan.

I have not forgotten one of the most lamentable and painfulevents that occurred, but as we did not hear of it until the fight was allover, it will do to bring it in here. Captain F.A. Gwin of the monitor Tecumsehhaving stood nobly up to his work, ran within 50 yards of Fort Morgan and wassunk almost immediately by the explosion of a torpedo under his ship’s bottom.All hands but the pilot and about 15 men were lost. Most of the escaped partylanded at Fort Morgan but the pilot, who had deserted from the Rebels about twomonths before, swam for dear life with five or six others of the crew and werepicked up by a boat and taken in tow by this ship where they all rendered whatassistance they could during the fight. Here we now lay, victors in Mobile Bay.Fort Powell, which was so furiously bombarded by the bomb vessels, wasevacuated and blown up. Grant’s Pass is now open and yesterday a tinclad camethrough and brought our mail. [Please see my recent post "Knocking Fort Powell into Pie: In Mobile Bay with the U.S.S. John P. Jackson."]

Admiral Franklin Buchanan

Admiral Franklin BuchananC.S.N.

After the fight, Admiral Buchanan sent a note to thecommander of Fort Morgan asking permission for one of our vessels to go outunder a flag of truce and carry him and the wounded of both sides to Pensacola.The request was granted and the Metacomet went next day and came backthis morning. The Rebel commander at Fort Morgan said they might go but had theimpudence to say also that she must return as we were all prisoners in here.Fort Gaines sent a flag of truce this morning and reports say the fort willsurrender tomorrow to the fleet. Our army is in her rear and has cut off allcommunication. As soon as Gaines surrenders, another and a deeper channel willbe opened and supplies without limit can be brought in. Fort Morgan must fallsooner or later and the city will soon follow suit.

Yesterday, the admiral published a complimentary orderthanking the officers and men of the fleet for so gallantly assisting him andcarrying out his orders and today another order was published requesting allcommanders and crews to join him in offering thanks to Almighty God for thesignal victory achieved through His power. The prisoners are distributed throughoutthe fleet. We have 18 men from the Tennessee and Selma. I met twomen from the Tennessee who were my old schoolmates at Annapolis. Theysaid the admiral and the Rebel crews were surprised to see our wooden shipsattack them as they believed themselves invulnerable.

I must speak of our loss. Seven were killed and one knockedoverboard and lost; we lost 38 in killed and wounded. The Hartford lost25 killed and 52 wounded. Our loss in proportion to numbers is greater thantheirs. Three of our men had their heads shot off and the pieces of skull bonesflying around actually wounded seven or eight men. The shell that took off thecaptain’s arm took off the head of a Marine at my 11-inch gun and wounded bothcaptains of the gun as well as the first loader, besides slightly woundedseveral others by scattering around fragments of bones which are now buried sodeep in the brackets as makes it impossible to get them out but by cutting thewood. The same shot disabled the gun. An 8-inch shot disabled an 8-inch gun inmy division and killed the first captain and first sponger. One of our powderboys had his passing box knocked overboard and jumped over after it and broughtit back on board. All our men behaved admirably.

August 8th

Rousing cheers are again given thismorning as the Rebel flag on Fort Gaines is hauled down and the American flagis run up in its place. A salute from the fort was fired in honor of the event.Three men were killed in my division and six wounded, but I escaped unscathedalthough covered with a shower of splinters and the brains of my unfortunate Marinebespattered my face. The Rebels say they were thunderstruck to see so manyships pass the forts as 300 torpedoes had been buoyed in the channel throughwhich we had passed, but the strong current must have swept them away. Thisship is severely impaired and will require 4 months of repairs before she willbe fit for duty again. We cannot get out of here until Fort Morgan surrenders.

Affectionatelyyour soon,

Edward N.Kellogg

For another account of Mobile Bay written by Lieutenant Kellogg's shipmate Ensign Charles Vernon Gridley, please check out "Damning the Torpedoes in Mobile Bay."

Source:

Letter fromLieutenant Edward Nealley Kellogg, U.S.S. Oneida, Waukegan WeeklyGazette (Illinois), September 3, 1864, pg. 2

June 25, 2025

Best Soldier in Bragg’s Army: Alfred Jackson Worsham of the 41st Mississippi

Comparisonsof who was the best soldier in either army during the Civil War have longserved as conversational fodder for many an armchair historian, but Captain JamesKincannon of the 41st Mississippi staked such a claim for one of hissoldiers, Alfred J. Worsham.

Worsham as he was called was hardly an imposing physicalspecimen: “He was box-ankled, knock-kneed, angular, and disjointed all over. Hecould not stand up straight and was never in line in the company’s formation duringthe entire term of his service. His energy was wonderful, his will indomitable,his courage superb, and his powers of endurance supernatural. He was never onthe sick list, was always at roll call, never shirked any duty, and did moreextra service than all the rest of the brigade put together. He was never idle,slept but little, and was always ready to volunteer for any hazardous work thatwas wanted. He was truly a wonderful man and seemed to have been made purposelyfor the place which he filled in the army.”

Captain Kincannon’s description of this extraordinarycharacter first saw print in the May 20, 1905, edition of the Macon Beacon;just a few months later Kincannon died at the age of 77 years old.

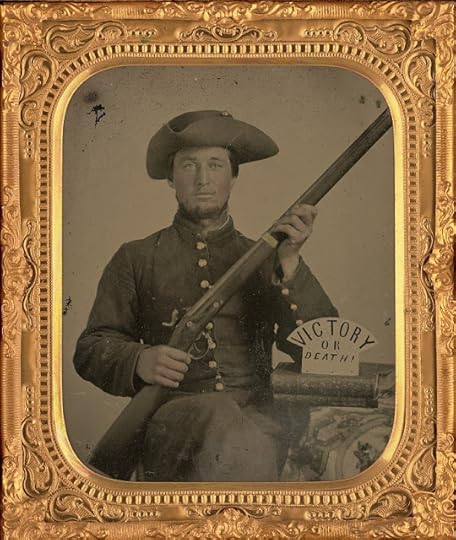

We'll never know whether this soldier was Alfred Jackson Worsham of the 41st Mississippi but the "Victory or Death" slogan seems like it would have fit this extraordinary character.

We'll never know whether this soldier was Alfred Jackson Worsham of the 41st Mississippi but the "Victory or Death" slogan seems like it would have fit this extraordinary character. The best soldier that ever buckled onthe armor of a holy cause was Alfred Jackson Worsham of Co. D, 41stMississippi Infantry. This is saying a heap for a single soldier, for every manof that glorious band of heroes was a true and loyal soldier and did his dutywell and nobly. But “Worsham” as he was known all through the brigade to whichthe 41st Mississippi was attached, did a great deal more than hisduty.

He was a man of unique character andwas endowed with a physical constitution that was as tough as a post oak andwith a mental organism and general personality that was sui generis. There wasnever but one Worsham. Without intending it, he could do more things to attractthe attention of everybody in reach of his performances than any man who everlived. He was entirely original in everything and had as many peculiarities aswere ever compressed in mortal form.

He was not large of stature and his limbs seemed to have beenarticulated by Dame Nature when she was in a dreamy mood. In putting all hisparts together, Nature seemed to be trying to create a masculine curio and shecertainly succeeded. He was box-ankled, knock-kneed, angular, and disjointedall over. He could not stand up straight and was never in line in the company’sformation during the entire term of his service.

His energy was wonderful, his will indomitable, his couragesuperb, and his powers of endurance supernatural. He was never on the sicklist, was always at roll call, never shirked any duty, and did more extraservice than all the rest of the brigade put together. He was never idle, sleptbut little, and was always ready to volunteer for any hazardous work that waswanted. He was truly a wonderful man and seemed to have been made purposely forthe place which he filled in the army. From the day the company was organized,Worsham became the “pack horse” of it and during every day of his service hecarried a load that would have made any other man either desert of commitsuicide. But he carried it by choice and never dreamed of adopting either ofthese alternatives to escape it.

From the outset, Worsham was chosen as the “head of his mess.”This meant he was chief cook and bottle washer. Joe Stokes, John Hodges, JoeRogers, John Menees, Jimmy Jones, John L. Jones, Joe Nuckles, and Worsham madeup the mess. Over it Worsham presided from the beginning and through all itschanges of members, he held his place to the entire satisfaction of all. Hedrew the rations, cooked and washed the dishes of the boys, all of which theylet him do willingly because he liked the job.

When the regiment was formed in April 1862, Worsham was “promoted”to the place of company “commissary” which he accepted but held on to his placeas head of the mess. He liked the place and kept it until he was disabled andhad to leave the army. As company commissary, he was always at his post andnever failed to get his full share of the best that was to be had. There wasnever a complaint against him and nobody every tried to oust him.

In addition to these important positions, Worsham became thebarber, first for the company and then for the regiment. He was so successfulin this place that the brigade adopted him and finally the division. Many ofthe higher ranking officers patronized him and he became famous throughout thearmy as a barber. He kept his scissors and razors sharp and his brush and soapalways clean. In this place he did much good and filled a great need in thearmy. In addition to these places, he became a kind of sutler and carriedtobacco for sale. As quartermaster, I allowed him to put his tobacco in JohnStewart’s wagon and hauled it for him. Sometimes he had as much as 100 pounds.He always had a plug or two in his knapsack for sale. He also carried a campstool and his barber’s outfit and was always ready to shave a customer night orday.

I remember that at Camp Moccasin opposite Chattanooga whenBragg’s army was starting on the Kentucky campaign, the 41st Mississippiwas brigaded with the 25th Louisiana. In that regiment were the “Tigers,”a company made up of stevedores and wharf rats from New Orleans. They nearlystole our regiment out of cooking utensils. Worsham carried the skillet andfrying pan of his mess about him and slept with them near him to keep theTigers from getting them. With his blanket across his shoulder, his camp stool,canteen, haversack, and frying pan, he looked more like a camel than a man.

In battle Worsham was conspicuouslyalert and daring. He never quailed under the most terrific fire. At Perryville,he fired 72 shots and his gun became so hot that he could not load it. Intrying to do so, he pushed the ramrod deep in the palm of his hand. He did notmind the pain but kept on fighting. When we had fallen back to Knoxville, hebrought me a certificate written in red ink covering a whole page of foolscappaper, narrating his exploits in the battle and asked me to sign it. I declinedto do so on the ground that such a certificate would be invidious. He thencarried it to Lieutenant [Robert E.V.] Yates who declined on the same plea. Oneof the boys asked Worsham what he wanted with it. “I want to have it framed andhung up in my home so that my boy can see it, and when some coward who wentafter water and did not come back till after the battle was over says hisfather did not do his full duty in that fight, he can point to it and tell himthat he is a liar,” Worsham replied. This closed the interview.

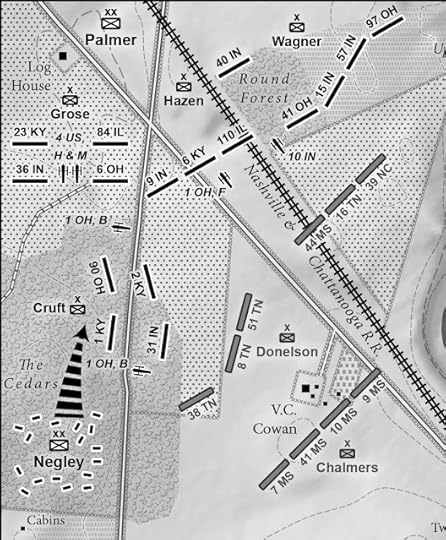

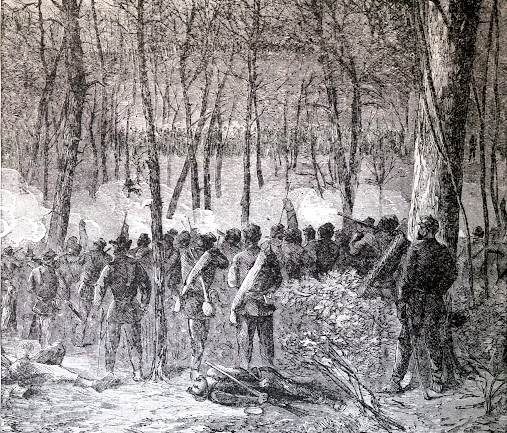

The 41st Mississippi, part of General James Chalmers all-Mississippi brigade, took part in the first assault on the Federal position at the Round Forest on the morning of December 31, 1862. Worsham sustained the wound that ended his war that morning.

The 41st Mississippi, part of General James Chalmers all-Mississippi brigade, took part in the first assault on the Federal position at the Round Forest on the morning of December 31, 1862. Worsham sustained the wound that ended his war that morning. At the Battle of Murfreesboro, Worsham’sleft arm between the elbow and the wrist was broken by a Minie ball. The bonepierced its way through the flesh and showed through the skin. Bragg retreatedfrom his position the next night. It was raining heavily and we had to find ourway through pitchy darkness. My train had been cut in two by another at acrossing of two roads and everything was in confusion. I was giving orderstrying to get out of the disorder.

To my great surprise, I heard Worsham calling me. Herecognized my voice and I knew his. He came close to the side of my horse andtold me his condition. I could only see the outline of his form. I made him getinto one of the wagons and carried him on to Shelbyville which place we reachedat daylight the next morning. Captain [William Baldwin] Augustus will recallthis terrible night and how we, drenched with rain, awakened an old Negro andhis wife and jumped into their bed for a little nap.

When I could do so, I examined Worsham’s arm which he hadbound up with an old piece of tent cloth. I tried to get him to go to the hospitalbut he would not do so. He prevailed upon me to get Dr. [John S.] Cain, thesurgeon, to send him home which he did. He never had anything done for hiswound but doctored it himself. It got well but was useless thereafter and hewas never fit for service again.

Worsham was an enigma. In his dealings with men, he wasbrusque, suspicious, and wary. He had but few friends but to these he was loyaland devoted. I chanced to be one of these and always found him true as steel. Thereis much more I could write of this strange genius. I regarded him as the bestsoldier in Bragg’s army. If Stonewall Jackson and Forrest had 100,000 men likehim, the Confederacy would have gained its independence. I know nothing ofWorsham’s posterity. If any of them should read this, they would do me a favorif they would write to me.

J.K.

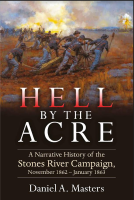

To read another account of Chalmers' brigade at Murfreesboro, please check out "Old Blucher Thompson Charges the Round Forest" or the Battle of Stones River page to access the more than 100+ blog posts I've written about the campaign. And be sure to pick up a copy of my award-winning campaign study Hell by the Acre available now through Savas Beatie.

Source:

WarReminiscences by Captain James Kincannon, Co. D, 41st MississippiInfantry, Macon Beacon (Mississippi), May 20, 1905, pg. 2

June 23, 2025

Draw Your Sabers and Weigh In: Stopping the Rout at Corinth

One of themost important roles played by cavalry during a battle was to serve as provostguards, providing security behind the lines by stemming the flow of men fromthe battle line. Sergeant Willard Burnap of the 2nd Iowa Cavalry told howhis company prevented a rout at the Battle of Corinth in October 1862.

“We received orders to station ourselves in the rear of theline of battle and stop all soldiers and officers from going to the rear unlessthey were wounded or belonged to the medical staff,” he wrote. “This is one ofthe most important positions that can be assigned to a company on thebattlefield. We were scarcely in line when the 80th Ohio regiment,broken, demoralized, and panic-stricken, came rushing back like frightened sheep.Other regiments, missing their support and knowing the danger when their linewas broken, seemed ready to follow. That regiment must be stopped or the day islost! I was nearest to them and putting the spurs to my horse was soon amongthem. In an instant, I was surrounded by a dozen or more of our company andsucceeded by entreaties, commands, and threats in stopping them. Their officersformed them and in turn rallied the rest as they came up. The last I saw of them;they were forming into line of battle with a cheer.”

Sergeant Burnap wrote the followingletter to his uncle Rev. E.G. Howe who shared it with the editors of the WaukeganWeekly Gazette; it ran on the first page of their October 25, 1862, issue.

The Model 1840 dragoon saber, popularly called the "wristbreaker" by the trooper who carried it, equipped most Federal cavalry regiments in the early years of the war. These sabers were produced both domestically and overseas, this particular example produced by N.P. Ames in Massachusetts in 1845.

The Model 1840 dragoon saber, popularly called the "wristbreaker" by the trooper who carried it, equipped most Federal cavalry regiments in the early years of the war. These sabers were produced both domestically and overseas, this particular example produced by N.P. Ames in Massachusetts in 1845. Corinth,Mississippi

October 8,1862

Dear uncle,

Since my last, the Army of theMississippi has been again victorious. One of the most splendid victories ofthe war has been achieved here. The slaughter of the Rebels was tremendous;their wounded cover an extent of ground larger than your public square beingplaced in tents as close as they can be set and each one filled to overflowing.I don’t know how many prisoners we have but the town is full of them.

The battle lasted two days, October 3rd and 4th,and the pursuit is still going on. We have captured the baggage and ammunitiontrains of the enemy, some of his artillery, and hopes are entertained ofgetting it all. The hottest of the fight was the morning of the 4thwhen the enemy concentrated all of his strength in one desperate charge,determined on entering the town for Price told them (so say the prisoners) thatthey should take dinner in Corinth.

At daylight on the morning of the 3rd, I was threemiles south of Jacinto in charge of a patrol when we had the first intimationof the attack on Corinth by hearing the cannonading in that direction. When Ireturned to camp, I found that the company, which had been left at Jacintountil the commissary stores were removed, had received orders to rejoin thebattalion three miles back. We joined the battalion, taking with us 17Mississippians who had volunteered in the Federal army and proceeded to Corinthwhere we arrived late in the afternoon. The fight was then going on justoutside of the breastworks on the west end of the town. It continued until toodark to see when both sides ceased firing and rested on their arms.

At the first break of dawn, a Rebel battery which had beenrun up and taken position during the night, opened fire, throwing shellsdirectly into town and causing a general stampede of hospitals, sutlers,citizens, etc., but not of soldiers. Soon after daylight our company wasordered to report to General Rosecrans in person. We proceeded through the townuntil we reached quarters. The fire of the Rebels had slackened some and two orthree siege guns seemed to be taking all of the responsibility of the battle onour side.

The colors of the 2nd Iowa Cavalry call out their participation in the Battles of Farmington, Boonville, Iuka, and Corinth, all located in northeastern Mississippi.

The colors of the 2nd Iowa Cavalry call out their participation in the Battles of Farmington, Boonville, Iuka, and Corinth, all located in northeastern Mississippi. We received orders to station ourselves in the rear of theline of battle and stop all soldiers and officers from going to the rear unlessthey were wounded or belonged to the medical staff. This is one of the mostimportant positions that can be assigned to a company on the battlefield. Ifone good company of cavalry had been placed in the rear of each brigade at theBattle of Bull Run, there would never have been a stampede as cowards are theones who commence stampedes and if they are kept in ranks, the brave willcertainly not run. Often a stampede which would if allowed to go on woulddemoralize a whole army. If halted in its commencement, it may be stopped byone determined mounted man who has a good saber and is not afraid to use itsside, back, and (if necessary) its point and edge upon dastardly cowards whowould run and leave their comrades to fight it out.

I was assigned to the command of the first platoon andstationed it as skirmishers at 15 paces intervals in rear of and overlookingtwo regiments of infantry and one regiment of sharpshooters. The firing by thistime had re-opened and soon after we had the pleasure of seeing a Rebel gunbrought into our lines and the battery which was shelling the town silenced.After the battery was silenced, the firing was confined to the sharpshooters inthe woods and they slackened so much that there began to be a general opinionthat they had given up the attack. We were recalled from our position anddismounted at headquarters to await events. It soon became apparent that thoughsilent they were not idle but were preparing for a general advance along thewhole line. Our right was in danger!

All was activity as artillery and infantry rushed to theright. We were ordered to mount and support a battery. And we, with the rest,rushed to the right following close upon the guns we were to support. Just thenthe battle opened. The Rebels charged in solid columns upon our works. Volleyafter volley of musketry is poured into their ranks and are answered by shot,shell, and musket balls with interest. Still, we go to the right under a heavyfire, past thundering batteries and staggering columns of infantry and reachedthe extreme right not a moment too soon. That flank is nearly turned; thebattery it supports is taken, the lines of infantry are wavering, recoiling,almost breaking. The Rebels by the thousands stand upon the breastworks of thecaptured battery and cheer on column after column of their comrades as theythrow themselves reckless of life upon our outnumbered infantry. It was thecritical moment of the battle. In 10 minutes, one side or the other must bevictorious.

General William S. Rosecrans commanded the Federal forces at Corinth in October 1862. That victory propelled him into his next assignment commanding the Army of the Cumberland.

General William S. Rosecrans commanded the Federal forces at Corinth in October 1862. That victory propelled him into his next assignment commanding the Army of the Cumberland. Quicker than thought our battery wheeled into line andunlimbered, the gunners springing from the caissons and putting their shouldersto the wheels. In an instant, they had the guns in a raking position throwingshot and shell, grape and canister, terror and death amidst the ranks of theever-exultant enemy. At the same moment, the battery wheeled into line, we receivedorders to deploy as skirmishers and stop the stream of cowards who were leavingtheir posts. “Draw your sabers and wade in,” said Rosecrans’ aide-de-camp justas we were deploying.

We were scarcely in line when the 80th Ohioregiment, broken, demoralized, and panic-stricken, came rushing back likefrightened sheep. Other regiments, missing their support and knowing the dangerwhen their line was broken, seemed ready to follow. That regiment must bestopped or the day is lost! I was nearest to them and putting the spurs to myhorse was soon among them. In an instant, I was surrounded by a dozen or moreof our company and succeeded by entreaties, commands, and threats in stoppingthem. Their officers formed them and in turn rallied the rest as they came up.The last I saw of them; they were forming into line of battle with a cheer.They other regiments, cheered by the timely opening of our battery and findingtheir line still firm, redoubled their energy and in five minutes the batterywas retaken and was thundering sweet music and death to them.

But hark, even over the roar of musketry and thunder of thecannon, away on the left, you can hear it swell. Cheer after cheer; now itrolls along the line. Regiment after regiment take it up and brigade afterbrigade passes it along. What is it? Now the right, which a moment ago wassilently, desperately and doggedly fighting against fearful odds, seemselectrified and pausing in the conflict gave three such hearty cheers that rendthe sky and fall to work again with redoubled force.

What does it mean? The Rebels are faltering, wavering,breaking! First the left, then the center, and finally on the right they giveground. The army which a short time ago was advancing in solid columns andwell-ordered lines is now recoiling in one confused mass. The fire of ourartillery slackens; the infantry soon followed by the artillery advance andplunge into the woods after the retreating foe. The battle has ended and thepursuit begun.

Since we came to Corinth our horses have nearly starved; wehave had only two or three feeds since we came here. We remain here as picketguards for the town. I don’t know where the regiment is but probably after theRebels.

To learn more about the Battle of Corinth, please check out these posts:

Brigham's War: Letters from the 27th Ohio Infantry, Part III

Interview with Brad Quinlin and the story of Pierre Starr, 39th Ohio Infantry

"Our Kirby" Colonel Joseph L. Kirby Smith and the 43rd Ohio at the Battle of CorinthThe Tug of War: A Hawkeye Captain at CorinthA Buckeye Remembers Scenes of Horror After the Battle of Corinth (80th Ohio)Back from the Dead: The 11th Ohio Battery at CorinthThe 63rd Ohio and the Struggle for Battery RobinettCapturing the Lady Richardson at CorinthUp to Time and Up to Contract: A Missourian Recalls CorinthWithin a Square of the Tishomingo Hotel: At Corinth with the 42nd AlabamaHouse to House Fighting at Corinth with the 50th IllinoisThe Sublime Horror of the Occasion: Memories of a Rebel Officer at CorinthCharging Battery Robinett: An Alabama Soldier Recalls the Vicious Fighting at CorinthAmong the Buzzing, Screaming Little Demons: Professor Dunn at CorinthCaptured at Corinth: A Wisconsin POW's StoryOur Whole Front was Swarming with Butternuts: A Missouri Gunner at Corinth

Source:

Letter from SergeantWillard A. Burnap, Co. I, 2nd Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, WaukeganWeekly Gazette (Illinois), October 25, 1862, pg. 1

June 22, 2025

Death at the Edge of the Cedars: An Account from the 29th Mississippi

Filing this one under the category of "I wish I had this when I wrote Hell by the Acre..."

Writing nearly 50 years after the Battle of Stones River, Private Edward A. Smith of Co. A, 29th Mississippi recalled the intensity of the fighting as his regiment approached the northern end of the cedar forest around midday on December 31, 1862.

"Our brigade had driven the Federals slowly but steadily through what is known in the history of the battle as the cedar grove. When the Federals reached the back side, they found a field 500 yards wife which, with the leaden hail we were throwing at them, they knew it was death to cross. Their officers got them halted and they turned on us with the fierceness of a lion at bay. They had no idea of going further and we had an idea that they must go further and there we stood 125 yards apart belching death at each other with all our might. In the meantime, Lieutenant Wilkins called my attention to a superb-looking officer on horseback who was evidently their commander. He urged me to do my best to shoot him, saying that he believed that with him out of the way, they would run. I stepped up to a tree, took deliberate aim and fired. When the smoke cleared away, my man had fallen. Another brigade, Sears [I think Smith is mistaken, this was most likely General James E. Rains’ brigade] came up just then and the enemy fled, but not half of them reached the other side. Many doubtless fell from exhaustion besides those who were wounded or killed. We advanced to the edge of the woods and lay down. Then their reserve batteries turned loose on us with such terrible effect that we were ordered to fall back 75 yards in the grove so they could not see us."

Throughoutthe spring and summer of 1910, Rev. Edward A. Smith provided a weekly column ofreminiscences of life in antebellum Oxford, Mississippi to the Oxford Eaglenewspaper. He devoted several columns to his military service with the 29thMississippi and the following account is drawn from those columns. It providesone of the finest descriptions of the late morning fighting at the edge of thecedars that I’ve yet encountered.

The 29th Mississippi fought at Stones River under the command of Brigadier General J. Patton Anderson who assumed temporary command of the brigade when General Edward Walthall went home on leave to attend to his sick wife. The brigade suffered horrendous casualties in its first assault on the cedars and the action Private Smith describes below occurred during the pursuit of Negley's division north through the cedar forest.

The 29th Mississippi fought at Stones River under the command of Brigadier General J. Patton Anderson who assumed temporary command of the brigade when General Edward Walthall went home on leave to attend to his sick wife. The brigade suffered horrendous casualties in its first assault on the cedars and the action Private Smith describes below occurred during the pursuit of Negley's division north through the cedar forest. An incident occurred at the Battle of Murfreesboro which iswell worth relating. Wading in almost a pool of their own blood as well as thatof their enemies, Walthall’s brigade [then under the command of General J.Patton Anderson as Walthall was on leave] had driven the Federals slowly butsteadily through what is known in the history of the battle as the cedar grove.When the Federals reached the back side, they found a field 500 yards wifewhich, with the leaden hail we were throwing at them, they knew it was death tocross. Their officers got them halted and they turned on us with the fiercenessof a lion at bay.

They had no idea of going further andwe had an idea that they must go further and there we stood 125 yards apartbelching death at each other with all our might. In the meantime, Lieutenant [WashingtonPorter] Wilkins called my attention to a superb-looking officer on horsebackwho was evidently their commander. He urged me to do my best to shoot him,saying that he believed that with him out of the way, they would run. I steppedup to a tree, took deliberate aim and fired. When the smoke cleared away, myman had fallen.

[Based on Smith’s location at the edge of the cedars and thetime this event likely occurred, it is possible that the officer he shot downwas Major Stephen D. Carpenter, commanding the First Battalion of the 19thU.S. Infantry of the Regular Brigade. Major Carpenter was shot from his horselate morning in this same approximate location as the Regulars were trying tocover the retreat of Negley and Sheridan’s divisions. For a Federal perspectiveon this event, please check out “Retrieving Major Carpenter: Joseph R. PrenticeEarns His Medal of Honor at Stones River.”]

Another brigade, Sears [I think Smithis mistaken, this was most likely General James E. Rains’ brigade] came up justthen and the enemy fled, but not half of them reached the other side. Manydoubtless fell from exhaustion besides those who were wounded or killed. Weadvanced to the edge of the woods and lay down. Then their reserve batteriesturned loose on us with such terrible effect that we were ordered to fall back75 yards in the grove so they could not see us.

Private John Shanks

Private John ShanksCo. K, 29th Mississippi

After shelling us for an hour, theysuddenly ceased. “Look out men,” said Lieutenant Colonel [James B.] Morgan, “somethingis going to happen. Be sure your guns are loaded.” In a few minutes a long lineof skirmishers, about 80 in number, could be seen advancing with all thesteadiness and accuracy of alignment of trained regulars which indeed theywere. Captain [George S.] Caldwell’s company [Co. D] was rushed forward to theedge of the woods to meet them and when they came within 50 yards, CaptainCaldwell called out, “You are within 100 yards of a Confederate line of battle!Thrown down your arms and come in!” [Lt. Col. Morgan assumed command afterColonel William F. Brantley was knocked senseless by a shell explosion duringthe regiment’s first assault on Negley’s division around 10 o’clock thatmorning.]

“Halt! Rally by fours and fire,”yelled their captain It was a silly order for men in an open field but theyobeyed to their utter undoing for they were nearly all shot down. Four of themhad picked up a corpse and started off with it, but two or three of them wereshot and the corpse was dropped. I learned afterwards that it was a company ofU.S. regulars who had voluntarily offered to go to the battle line where thebrave officer fell and return with his body or died in the effort.

He was reported to me by one who said he knew all the circumstancesand said the officer was one of noblest, bravest, and knightliest charactersthat ever gave a command or waved a sword on the field of battle. He was acolonel and thought to be commanding a brigade and I doubt not he was theofficer whom it was my lot to kill, or at least try to kill, on that fatefulfield. A splendid monument has been built near where he fell dedicated to hismemory. [The Regular Brigade monument stands at the center of Stones RiverNational Cemetery.]

To learn more about the Battle of Stones River, be sure to purchase a copy of my campaign study Hell by the Acre, recently awarded the Richard B. Harwell Award from the Atlanta Civil War Roundtable as best Civil War book of 2024. Available now through Savas Beatie.

Source:

Memoirs ofPrivate Edward A. Smith, Co. A, 29th Mississippi Infantry, OxfordEagle (Mississippi), August 19, 1910, pg. 2; also, August 25, 1910, pg. 2

June 21, 2025

A Huckleberry Frolic at Allatoona Pass with the 15th Illinois

RichardShatswell joined the 15th Illinois in January 1864 when the regimentwas home on veteran’s furlough. He was an unusual recruit- the 47-year-oldMassachusetts native was twice the age of the average Union soldier. Leaving behinda farm in Waukegan, Illinois, he joined the 15th Illinois along withhis son George and soon was on the road to join Sherman’s army in northernGeorgia. The regiment’s first assignment was guarding Allatoona Pass. Theycould hear the guns of the front in the distance but relative quiet allowed themen to focus on improving the defenses and their living quarters.

“We are encamped on a very high hill which commands the passthrough these hills,” he wrote. “We have little huts built in the side of themountain about eight- or nine-feet square. Three or four men sleep together.Our huts are made of good, planed boards and if you would like to know where wegot our lumber, I would refer you to the frame of a large flouring mill anddwelling house standing at the foot of the mountain. The Rebels destroyed partof the machinery so the Yankees should not use it, but they did use it and intwo or three days after we arrived here, every board and every piece of sidingwas carried 400-500 feet up the mountain and converted into huts for Yankees.”

Shatswell’s letter describing hisinteractions with Southern civilians and quiet duty at Allatoona Pass firstappeared in the July 9, 1864, edition of the Waukegan Weekly Gazette.

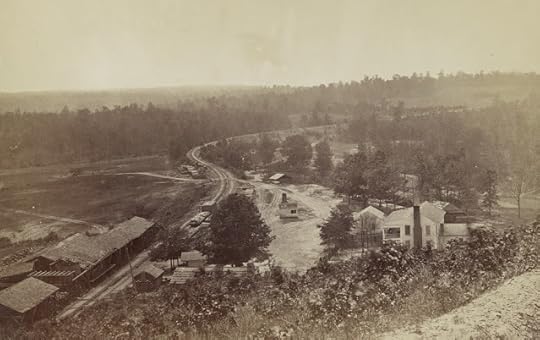

Allatoona Pass, Georgia, looking south along the Western & Atlantic Railroad towards Atlanta. "General Sherman considers the place of great importance; so much so that he has ordered it to be held at all hazards," our correspondent noted. His regiment, the 15th Illinois Infantry, was among the three regiments assigned to guard the pass in June 1864.

Allatoona Pass, Georgia, looking south along the Western & Atlantic Railroad towards Atlanta. "General Sherman considers the place of great importance; so much so that he has ordered it to be held at all hazards," our correspondent noted. His regiment, the 15th Illinois Infantry, was among the three regiments assigned to guard the pass in June 1864. (Library of Congress)

AllatoonaPass, Georgia

June 16,1864

We left Paducah about the 12thof May and arrived at Clifton, Tennessee on the 14th; on the 16thwe left and took our line of march across the country for nearly 300 miles byway of Pulaski, Tennessee, Decatur, Huntsville, Somerville, Warrinton, and CedarBluffs, Alabama. We have at length arrived here at Allatoona Pass which we arenow guarding.

The country through which we have passed is mountainous mostof the way and poor tillage land but found most excellent water in abundance, agreat blessing to soldiers on the march. The inhabitants appear very destituteand are anxious for peace on any terms and they say if our soldiers don’tconquer the Rebels soon and bring provisions into the country, they must soonstarve. This appears to be the feeling of the poor class all along the road andI think they mean it as there are families around where we are now camped thatdo not know where to get their next meal.

When we arrived at Cartersville, Georgia, the inhabitantsseemed to be as glad to see us as our own folks would be to see us come home.They cursed Jefferson Davis and the whole Confederate crew and wanted to seethe stars and stripes waving over the whole land once more. A good part of theemployees on the railroad are citizens of this part of the country. But theYankees are a great wonder to them; they say they never saw such people andthat the Yankees can do anything for what has appeared to them asinsurmountable, the Yankees overcome quite easily.

Allatoona Pass looking north towards the hill where the first picture in this blog post was taken.

Allatoona Pass looking north towards the hill where the first picture in this blog post was taken. For example, when we were coming to Raccoon, Sandy, andLookout Mountains in Alabama, the inhabitants told us we could not pass themountains for when they went that way they had to take their light wagons apartand take them down the other side of the mountain in pieces, but we got oursover the three mountains safely with the exception of three or four thatcapsized after dark. Ours were large six mule wagons, heavily loaded withprovisions and ammunition for the 17th Army Corps.

When General Sherman was coming through, the citizens toldhim he never could pass through Allatoona as Johnston had made it absolutelyimpregnable, but Sherman went through and if Johnston had not skedaddled, hewould have been caught in his own trap and now they say when Sherman getswithin 7 miles of Atlanta, he will get whipped but time will tell whether hewill or not. To show you how Sherman hurries matters, I will state that most ofthe timber for the railroad bridge across the Chattahoochee River is alreadyout and ready for framing. It lies now at the foot of this mountain along therailroad and the probability is that three days after Sherman crosses theriver, the bridge will be up and the cars across as he keeps his communicationopen as fast as he goes.

Private George P. Shatswell

Private George P. ShatswellCo. I, 15th Illinois Inf.

We are encamped on a very high hill which commands the passthrough these hills. Up and down, we have our cannons in position on top of thehill and our rifle pits finished as there has lately been a depot for militarystores established here. General Sherman considers the place of greatimportance; so much so that he has ordered it to be held at all hazards and the14th Illinois, 15th Illinois, and 53rdIllinois regiments are guarding it and as they are mostly veterans and wellknown to Sherman, I presume they will do their duty.

The weather is nice and cool in these mountains and we havethe best of water, a great blessing in this climate. We have little huts builtinto the side of the mountain about eight- or nine-feet square. Three or fourmen sleep together. Our huts are made of good, planed boards and if you wouldlike to know where we got our lumber, I would refer you to the frame of a largeflouring mill and dwelling house standing at the foot of the mountain. TheRebels destroyed part of the machinery so the Yankees should not use it, butthey did use it and in two or three days after we arrived here, every board andevery piece of siding was carried 400-500 feet up the mountain and convertedinto huts for Yankees.

We can hear every discharge of Sherman’scannons and see the smoke and ever since daylight today the discharges havebeen more frequent than heretofore. My son George was out to the frontyesterday to see the 96th Illinois boys. They were in excellentspirits and had full faith in Sherman’s ultimate success and they gain someground every day. George came back on the cars with 600-700 Rebel prisoners. Heknew several as they were the same ones Grant paroled at Vicksburg. They saidif we took Atlanta, they though the soldiers would not fight as they had butwould become disheartened and give up.

Yoursrespectfully,

RichardShatswell, 15th Illinois Infantry

P.S. If anyof your friends wish for a huckleberry frolic, by taking a trip down here theycan get all they want as the hills are covered with them.

Source:

Letter fromPrivate Richard Shatswell, Co. I, 15th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, WaukeganWeekly Gazette (Illinois), July 9, 1864, pg. 2

June 20, 2025

Into the Wilderness with the 122nd Ohio

Corporal Charles Willey of the 122nd Ohio sustained the second and third of his four wartime wounds when his regiment charged the Confederate line during the last day of the Battle of the Wilderness. Located on the far right of the Union line, the Ohioans charged the works held by John Pegram's Virginia brigade.

"On the morning of the 6th our brigade made a charge on the Rebel works," he stated. "They held their fire until we were about 100 yards from them. When they opened on us, such a sight I never want to see again. It seemed as if every other man had fallen, either killed or wounded. It was terrible to see the brave boys falling on every side. I had fired but a few shots when a ball came through my haversack, striking me on the hip. I first thought I was badly wounded but I found I was only bruised. In a short time, another ball struck me on the left leg just above the knee and about two inches from the wound I received at Winchester. The ball did not bury itself in the flesh and I took it out myself. However, it affected the old wound so much that I was quite lame."Corporal Willey’s account of theBattle of Wilderness first saw publication in the June 2, 1864, edition of the ZanesvilleDaily Courier. In this charge, the 122nd Ohio lost 120 men.

U.S. GeneralHospital, Annapolis, Maryland

May 26, 1864

I thought you would like to have someaccount of our movements from the time of leaving our winter quarters. Westarted on the morning of May 4th and that evening crossed theRapidan and camped. The morning of the 5th we took up the line ofmarch, moving in the direction of the old Wilderness Tavern, our corps movingon one road. Going some 4 or 5 miles, we were ordered back to where we hadcamped the night before. About an hour after we got there we were ordered tomove forward again. This time we went almost to the tavern and then wereordered back to a road that led into the Wilderness on the extreme right of ourline of battle. We were drawn up in line of battle and lay there some 2-3 hoursthen were relieved by a brigade of Burnside’s corps.

Our brigade went further to the leftin a position to support a brigade that was engaged. We were under fire untilthe fighting stopped at about 9 o’clock that night. Then our company with someothers was ordered out to picket in front of the regiment. We were withinspeaking distance of the Rebels and we had to keep a sharp lookout while theydid the same. There was picket firing all night but it did not amount to much.The Rebs were cutting down trees and building breastworks all night and workedas if for life. We could hear them plainly but could not see them.

On the morning of the 6thour brigade made a charge on the Rebel works. They held their fire until wewere about 100 yards from them. When they opened on us, such a sight I neverwant to see again. It seemed as if every other man had fallen, either killed orwounded. It was terrible to see the brave boys falling on every side. I hadfired but a few shots when a ball came through my haversack, striking me on thehip. I first thought I was badly wounded but I found I was only bruised. In ashort time, another ball struck me on the left leg just above the knee andabout two inches from the wound I received at Winchester. The ball did not buryitself in the flesh and I took it out myself. However, it affected the oldwound so much that I was quite lame.

"An assault was ordered at daylight but from some cause was not made until about 9 a.m., the 122nd being on the left of our brigade and by some mistake unsupported by any second line. The order being to press on without firing, our regiment moved at a run without any caps on their guns and were pushing for the enemy's works when troops on both right and left of us began firing and laying down. I then ordered my wing of the regiment to lie down and suppose Colonel Ball did the same with his wing. Firing from our lines began, our regimental colors being nearer the Rebel works than any other part of the line. After half an hour or more, the troops on our right began to fall back as did those on our left and then did the 122nd Ohio, having suffered heavily. Thus the assault was a failure." ~ Lieutenant Colonel Moses M. Granger, 122nd Ohio

When I was wounded, I was beside AndrewVoll; he had not been touched when I left. The wounded bots that came to therear after I did said they saw Voll, Frost, and Sloan fall before they left. I sawa great many fall but could not tell who they were as they generally fell ontheir faces. When I started to the rear, I thought the balls came as thick asthey did in the front and the shells were worse. We passed over the groundwhere they had fought on the 5th there was quite a number of Rebeldead scattered through the woods with some of our own men. In some places, theRebel dead lay in heaps. It was a sad sight to see men lying there where theirfriends will never find them, will not even know what their fate was. Many ofthe wounded that were not able to get away perished in the flames in theWilderness. The fire was caused by shells exploding among the dry leaves.

When we got out of range of the ballsand shells we found the field hospital where the surgeons were dressing woundsas fast as possible and sending the wounded to the brigade hospitals. Ourhospital was at the old Wilderness tavern. That night, orders came to move thehospitals as it was thought that would be the battleground the next day. Allthat were able had to walk while the others were placed in ambulances. Thetrain was some 3 miles long.

On the 7th we arrived atthe Chancellorsville battlefield where we stopped awhile expecting to go onthrough to Rappahannock Station on the Alexandria Railroad but somethingprevented us from moving. On the morning of the 8th, we started inthe direction of Spotsylvania but could not get through that way; we were thenturned back on to the plank road leading to Fredericksburg. The train movedvery slow and we traveled all night, reaching Fredericksburg at noon on the 9th.Every house, church, and yard that could be used for that purpose were taken ashospitals and almost everywhere on the streets you could see wounded men gladto lie down quietly after their painful ride. Everything was done that possiblycould be and great praise is due to Dr. Bryan, Chaplain Houston of our regimentand Mr. Tucker, our hospital steward. They went with us to Fredericksburg andwere busy night and day attending to the sufferers, making them as comfortableas possible with the scanty means they had for supplies were getting low.

On May 10th all that wereable to travel were directed to Belleplain Landing. We crossed the Rappahannockand took the road leading to the landing which is distant 8 miles. BelleplainLanding is on the Potomac and there we found the Sanitary and ChristianCommissions doing all they could to relieve the sufferers. About midnight, theboat came to take us to Washington where we arrived on the 11th andwere immediately taken to the hospital where we were fed and got clean clothes.We left there on the 18th and went to Baltimore to take a boat forAnnapolis where we arrived on the morning of the 19th.

I am doing very well but I do notthink I will be able to march. Concerning Robert Sloan, I know nothing onlythat he was reported killed. Voll and Frost the same. I presume you haveparticulars before this. We have everything here that we need.

To learn more about the Battle of the Wilderness, please check out these posts:

Coming Out with a Whole Hide: A Sharpshooter Describes the Wilderness

Grant the Great will be no more: An Alabamian at Wilderness and Spotsylvania Courthouse

Sources:

Letter fromCorporal Charles T. Willey, Co. A, 122nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, ZanesvilleDaily Courier (Ohio), June 2, 1864, pg. 2

Letter fromLieutenant Colonel Moses M. Granger, 122nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, ZanesvilleDaily Courier (Ohio), May 25, 1864, pg. 2

June 18, 2025

Blundering through Georgia: The 4th Indiana Cavalry and McCook’s Raid

To Lieutenant William H.H. Isgrigg of the 4th Indiana Cavalry, the blunders of McCook's cavalry raid in July 1864 occurred after the cavalrymen had completed a round of destruction, then waited around for hours before moving on to their next mission. The excessive delays gave the Confederate forces time to gather their troops and eventually corner the Federal horsemen. By July 30th, they were well and truly trapped.

"We attempted to go around them but were only led into a trap where some of the hardest cavalry fighting of the war took place," he wrote. "Up to this time, I had not lost a man but here I lost eight men captured on the first charge. In a few minutes afterwards, they charged our pack train and I lost four more men. In this charge, they cut off our brigade entirely from our force. We made several charges to gain the command, but finding it useless, we had to give up that part of the work and look for some way to get out of the country and to keep from being captured. This we did by pressing a Negro as a guide to take us to the Chattahoochee River where we finally arrived without losing another man. We arrived at the river at 10 p.m. but found nothing but three small canoes to cross in. We first sent over our saddles in the small boats and then drove our horses into the stream so they could swim out on the other side."

Lieutenant Isgrigg with the survivors of his company made it into Federal lines; he had started the raid with 25 men. He ended it with 11. His description of McCook’s Raid first saw publication in the August 18,1864, edition of the Aurora Journal.

The Model 1860 light cavalry saber was the preferred weapon for short range combat.

The Model 1860 light cavalry saber was the preferred weapon for short range combat. Vining’sStation, Georgia

August 2,1864

I will write a few lines this morningfor the benefit of those who have friends in Co. B. Ere this you have heard ofMcCook’s cavalry raid through the rear of Atlanta. This raid started on the 27thultimo from near this place and crossed the [Chattahoochee] river at 3 p.m. onthe 28th, meeting but a few ford guards who fell back on ourapproach.

Just at sundown of this day, we made acharge and succeeded in taking Palmetto Station on the Montgomery & WestPoint Railroad. We destroyed the railroad track for three miles, burnt a trainof cars, and destroyed several thousand dollars’ worth of government stores. Atthis place, our blunders began. After we had done all the damage we could, westopped for two hours instead of starting off as soon as we got through. Thecause of this delay will develop in due time.

By 10 p.m. we were on the road to Fayetteville.It was raining as hard as I ever had the pleasure of seeing rain fall. At 11:30,we came upon a train of wagons belonging to General [Clement H.] Stevens’headquarters at White River. This we destroyed and killed some 500 mules. Wefound wagons camped all the way from here to Fayetteville, two or three in aplace, all of which we destroyed before arriving at Fayetteville at daylight onJuly 29. Here again we found government stores which were soon in a very warmcondition. Here again we stopped for four hours when all we had done wasaccomplished in half an hour.

At 8:30 a.m., we are again drivingthrough the country, taking wagon after wagon until we have destroyed somethingnear 500 wagons, all heavily loaded with fine clothing belonging to differentheadquarters. We also killed 600 horses and miles, captured 288 prisonersincluding five colonels, four majors, seven captains, and eight lieutenants.Now we are at the Atlanta & Macon Railroad, turning it upside down, burningthe ties and heating the rails so that they are of no use. Six miles of theroad was destroyed by the time the work was stopped and our men called tohorse.

Here again as soon as our work was done, we remained for two hours andas soon as we started, our rear was attacked by 1,000 infantry that had beensent down to within a mile of us. This detained us some four hours longer,giving the Rebels plenty of time to concentrate a sufficient force on the WestPoint & Macon Railroad to hold us until their cavalry could come on ourflanks. In this skirmish, we had one man in Co. L killed and Major John Austin wasslightly wounded in his right arm. This was all the regiment lost but someother regiments lost very heavy.

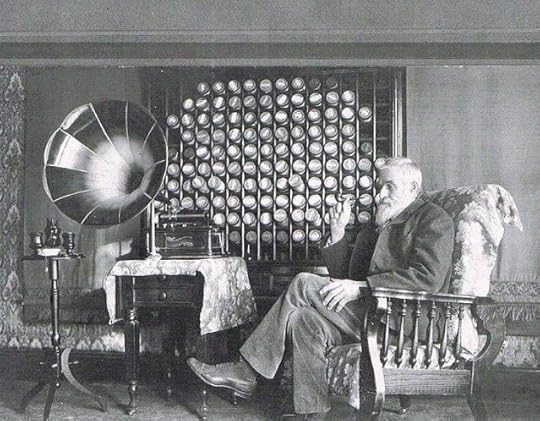

Private Taylor Langford, Co. F, 4th Indiana Cavalry joined the regiment in March 1864.

Private Taylor Langford, Co. F, 4th Indiana Cavalry joined the regiment in March 1864. By dark, we were again on the run fornow it was to see which force could go to the other railroad first. We arrived thereare 9:30 a.m. on the 30th but finding the Rebels there in too stronga force for us, we attempted to go around them but were only led into a trapwhere some of the hardest cavalry fighting of the war took place. Up to thistime, I had not lost a man but here I lost eight men captured on the firstcharge. In a few minutes afterwards, they charged our pack train and I lostfour more men.