Daniel A. Masters's Blog, page 10

February 23, 2025

Guarding the Road to Chattanooga: The 84th Indiana on September 19, 1863

Indiana at Chickamauga

In part oneof the 84th Indiana at Chickamauga series, Thomas Addington, thenserving as a private in Co. A, describes his regiment’s efforts to hold theirposition on the Union far left defending the army’s road connection toChattanooga on Saturday, September 19, 1863.

In a fight that developed that morning near Peavine Creek, Addingtonsaid “just after crossing the creek, we began to hear scattering shots from ourskirmishers, replied to vigorously by the enemy, while spent balls began todrop in our midst. Hurrying forward, we took up a position behind the fencewhere we had laid the night before. Here we waited for our skirmishers to fallback into line; we did not have long to wait. They soon came straggling throughthe weeds and briars with which the fields were overgrown. A bluecoat would beseen to pop up, fire at the approaching foe, then drop down among the weeds andcontinue his retreat. Arriving at the fence, a final shot would be fired andthen over the fence and down into line would go the daring soldier.”

This account first saw publication in the May 21, 1885,edition of the Weekly Toledo Blade as part of their "CampFire" series featuring soldiers' accounts of the Civil War.

The morning of September 19, 1863, rose clear and cold,everything was crisp and white with frost. When the first streaks of dawn werejust showing in the east, word was quietly passed along the bivouac line and wesilently fell in and took up the line of retreat. One and half miles back onthe Rossville road stood the Pisgah Church, on old structure on the west of theroad surrounded by open woods with slight swells or low wooded hills in therear. Here we halted, formed in line just back of the church and at rightangles with the road. We stacked arms and built fires to warm our benumbedlimbs and to prepare breakfast. Camp kettles and skillets (the first in theform of tin cups, and the latter of sharpened sticks) were called into use andsoon the woods were filled with the tempting odor of broiling bacon andsteaming coffee while jest and song and merry laughter were heard on everyside.

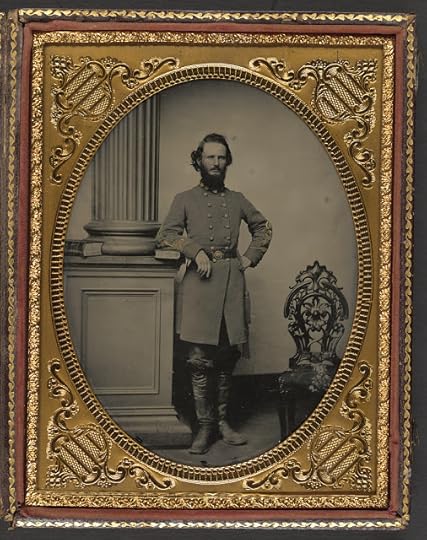

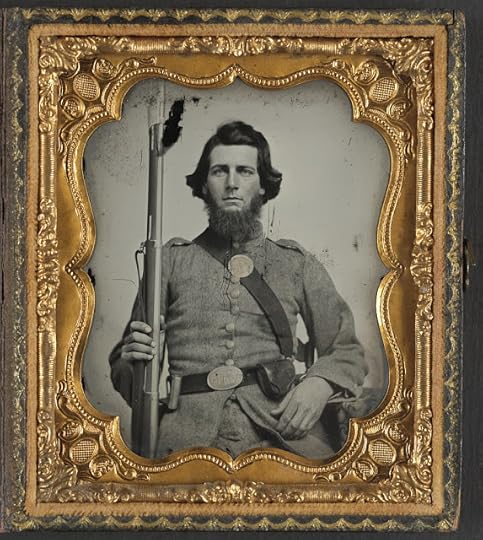

David Parshall Demree was born near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1838 and moved to Dublin, Indiana with his family in the late 1850s. He joined Co. C, 84th Indiana Volunteer Infantry in August 1862 and was appointed corporal. Wounded in the Battle of Chickamauga, he later transferred to the Veterans Reserve Corps in May 1864. Corporal Demree was prominent in both the G.A.R. and temperance efforts in the late 1800s and passed away in 1909 as the result of an operation. Census records indicate he worked as a house painter and wall paper hanger post war.

David Parshall Demree was born near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1838 and moved to Dublin, Indiana with his family in the late 1850s. He joined Co. C, 84th Indiana Volunteer Infantry in August 1862 and was appointed corporal. Wounded in the Battle of Chickamauga, he later transferred to the Veterans Reserve Corps in May 1864. Corporal Demree was prominent in both the G.A.R. and temperance efforts in the late 1800s and passed away in 1909 as the result of an operation. Census records indicate he worked as a house painter and wall paper hanger post war. Our rude breakfast over, volunteerswere called for and from the many who responded, three were selected as scoutsand sent forward with instructions to advance cautiously and learn as much aspossible as to the strength and position of the enemy. You will remember thaton the preceding night we lay on our arms on the north side of a farm, a shortdistance south of Peavine Creek with the enemy about one-fourth of a miledistant in the edge of the timber south of the same farm. Here our scouts foundthem in force and after sending a volley into their midst, they made good theirretreat in safety to their regiment where they arrived about 10 o’clock.

From the report of the scouts and fromthe demonstrations on the 18th, it was evident that we wereconfronted by a large body of Rebels, and yet General [Walter C.] Whitakerdivided the small force under his command and sent forward two regiments, the40th Ohio and the 84th Indiana, holding backthe 115th Illinois and 96th Illinois and the 18th Ohio Battery as a reserve. The command of thelittle handful of men sent forward was given to the colonel of the 40thOhio [Lieutenant Colonel William Jones] who detailed Cos. C and F of the 84thIndiana as skirmishers and sent them forward, following up with the remainderof the two regiments.

Just after crossing the creek, webegan to hear scattering shots from our skirmishers, replied to vigorously bythe enemy, while spent balls began to drop in our midst. Hurrying forward, wetook up a position behind the fence where we had laid the night before. Here wewaited for our skirmishers to fall back into line; we did not have long towait. They soon came straggling through the weeds and briars with which thefields were overgrown. A bluecoat would be seen to pop up, fire at theapproaching foe, then drop down among the weeds and continue his retreat.Arriving at the fence, a final shot would be fired and then over the fence anddown into line would go the daring soldier. One, a boy of 16 summers who hadcome as a recruit only two weeks before, came in thus and took his place by myside and yet that boy, fresh from his peaceful home, had been in the skirmishline and right in the very face of the enemy.

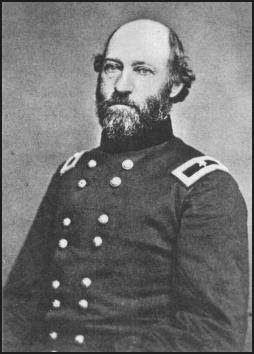

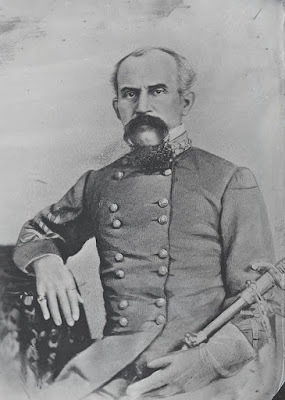

Brig. Gen. Walter C. Whitaker

Brig. Gen. Walter C. WhitakerAnd now the order passed along theline, “Keep cool and aim low. Make every shot tell, fire at will as you see achance.” Every man of the two regiments laying in the laps of the worm fence orstanding behind trees, loaded and fired as coolly and as deliberately as ifthey had been firing at a target with no enemy in view. But the murderous ballswere doing their terrible work and all around men were falling dead or wounded.For one terrible hour, these two regiments bravely confronted a whole divisionof Longstreet’s veterans and held them in check. But the force against us wasoverwhelming; we were flanked both on the right and the left while at leastdouble our number were pressing us to the front. To remain longer meant deathor capture. There was nothing for us but to fall back and when the time came,we did not stand on the order of going but went with a will. The two wings weresweeping round to close up in the rear of us when we ceased firing and startedfor the gap yet open as fast as our legs would carry us. Run? Yes, we did run,otherwise we would not be here to tell of it today.

The colonel of the 115thIllinois [Colonel Jesse H. Moore] had heard the firing a mile and a half awayand without waiting for orders, he called his men into line. “Boys,” said he, “the40th and 84th are in trouble out yonder; we will go andsee them through it. Forward!” Just as the last of us were crossing the creek,we came up on a sweeping trot with the men at his heels on the run. Salutingthe officers, he inquired “Where do you want my regiment? Where shall I fallin?” As no officer could find his tongue just then, a private in the ranksresponded, “Right along the bank of this branch, colonel.” This hint was atonce acted upon. Instantly, the men wheeled into line along the margin of thelittle stream where they were completely hidden from the approaching Rebels bya thicket of bushes in the rear and of briars on the opposite bank.

“Steady men, hold your fire till youget the word, then shoot to kill.” The words were low and quiet but theyevinced a terrible purpose. On came the yelling and triumphant horde, tearingthrough the thicket of briars. Silent and watchful stood our panting men, eachwith his finger on the trigger, ready for the word.

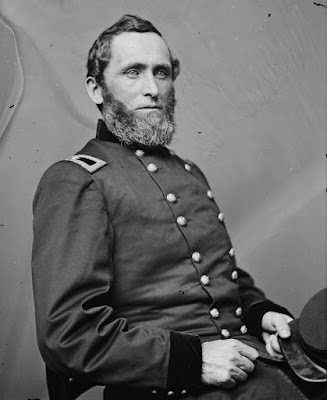

Colonel Jesse Hale Moore led the 115th Illinois Volunteer Infantry throughout the war and was awarded a brevet promotion to brigadier general in May 1865.

Colonel Jesse Hale Moore led the 115th Illinois Volunteer Infantry throughout the war and was awarded a brevet promotion to brigadier general in May 1865. And now the line of graycoatsrose above the briars not a dozen rods away. Raising himself in his stirrups,the colonel thundered forth one word which was heard clear and distinct aboveall the noise and confusion: “Fire!” Such a volley I never heard before orsince from one regiment, and perhaps greater execution was never done by anequal number of men. Every rifle appeared to speak at once and every ball to gostraight to the enemy. Instantly, the yelling demons stopped in their madcharge; then imagining themselves drawn into a trap, they turned and fled precipitately.It was fortunate for us that they did so; had they pressed on, they couldeasily have captured three regiments.

The pursuit being thus checked, ourretreat was continued in a better order than in which it had begun. At the oldPisgah Church, we met reinforcements that were coming to our assistance. Herewe halted and a line of battle was formed just back of the position occupied byour brigade in the morning. We watched and waited, monetarily expecting anattack. But the day waned and night set in with no further demonstration on thepart of the enemy. Throughout the day and far into the night we could hear theroar of artillery far to the right where the sanguinary conflict was raging inall its fury. Our position for these two days was on the extreme left, guardingthe approach to Chattanooga by the way of Rossville and Missionary Ridge.

Source:

“Granger’sReserves at Chickamauga,” Private Thomas Addington, Co. A, 84thIndiana Volunteer Infantry, Weekly Toledo Blade (Ohio), May 21, 1885,pg. 2

February 19, 2025

A Hot Time in Virginia: On Cedar Mountain with the 14th Georgia

The initial moments entering combat at Cedar Mountain were anything but encouraging to the men of the 14th Georgia. The regiment had scarcely entered the field when the colonel suffered a wound in his hand, forcing him to turn over command to the lieutenant colonel Once the men got into line, the sight before them dripped with peril as remembered by one veteran.

"Emerging from the woods near the road by which the brigade had approached the field, it was met by General Taliaferro’s brigade, Jackson’s division, falling back before the advancing enemy," he wrote. "The 14th was cut off from the brigade by Taliaferro’s retreating men. Some of the men of the 14th faltered for a moment. The danger of a panic was imminent. The enemy, encouraged by the retreat of Taliaferro’s brigade and confident of victory, were advancing and about reaching a point at which their line would have prolonged our battleline and were within a stone’s throw of and on the flank of Purcell’s Battery. This was a critical and trying time, but it lasted only a moment. Colonel Folsom caught the colors of the 14th Georgia and bearing them forward, called upon his officers and men to follow. Nobly and gallantly did they respond to the call. Without flinching, the 14th advanced to meet the confident foe and by their well-directed volleys soon brought them to a stand."

This account of the Battle ofCedar Mountain, penned by a soldier in the 14th Georgia Infantrywriting under the penname of “Dixie,” first saw publication in the August 21,1862, edition of the Atlanta Southern Confederacy newspaper.

Colonel Felix Price of the 14th Georgia Infantry was wounded in the hand early in the engagement at Cedar Mountain; regimental command devolved upon Lieutenant Colonel Robert Folsom.

Colonel Felix Price of the 14th Georgia Infantry was wounded in the hand early in the engagement at Cedar Mountain; regimental command devolved upon Lieutenant Colonel Robert Folsom. There are fewregiments from Georgia that have seen harder service than the 14th;since the Battle of Seven Pines, it has been in six general engagements in eachof which it has acquitted itself with honor to the state from which it hails.In some of these battles, it lost as high as 25% of the number carried intoaction.

But the proudest day for the 14thGeorgia, as it was for many others, was the 9th of this month at theBattle of Cedar Run between Orange and Culpeper Courthouses. The regiment is inGeneral A.P. Hill’s division and composes part of the Third Brigade, consistingof the 14th, 35th, 45th, and 49thGeorgia regiments, commanding by acting brigadier Edward L. Thomas, colonel of the35th Georgia.

The day was oneof the hottest ever felt and the troops were marched from daybreak until 3 p.m.when the Third Brigade filed off from the road to some woods on a high hillcommanding a view of the valley beyond for several miles. This position hadbeen selected by General Jackson as his temporary headquarters. In the distancecould be seen a Yankee force of cavalry on picket and still farther on werevisible moving bodies of men and wagons rolling up dense clouds of dust. Ourartillery was winding along the base of the mountains through thickets andalong the little ravines for the purpose of getting into position. Long line ofslow marching infantry was following different directions, their bright musketsgleaming in the light of the evening’s sun while now and then a solitaryhorseman might be seen dashing along the valley now so quiet and peaceful, butsoon to be the scene of fearful noise, confusion, pain, and death.

Meanwhile OldStonewall sat quietly studying a map spread out before him. At length, a signalflag near him gave a single wave down, an instant after the boom of a cannonaway down the valley reverberated through the mountains and along the valley.The ball struck in the midst of the Yankee cavalry and those hitherto statue-likelooking beings suddenly became wonderfully animated. They put into exercisetheir powers of locomotion and went scampering away at the top of their speed.Cannon was answered by cannon and battery by battery. Clouds of smoke and dustwent rolling up and spreading out over the valley. It was not about 4 p.m.Colonel Thomas (35th Georgia) was ordered to the field near thecenter of the line and in supporting distance of Purcell’s Battery. Colonel Felix Price of the 14th Georgia was wounded in the hand and retired beforethe regiment was brought actively into the engagement; the command thendevolved upon Lieutenant Colonel [Robert W.] Folsom.

Emerging fromthe woods near the road by which the brigade had approached the field, it wasmet by General Taliaferro’s brigade, Jackson’s division, falling back beforethe advancing enemy. The 14th was cut off from the brigade byTaliaferro’s retreating men. Some of the men of the 14th falteredfor a moment. The danger of a panic was imminent. The enemy, encouraged by theretreat of Taliaferro’s brigade and confident of victory, were advancing andabout reaching a point at which their line would have prolonged our battlelineand were within a stone’s throw of and on the flank of Purcell’s Battery.

This was acritical and trying time, but it lasted only a moment. Colonel Folsom caughtthe colors of the 14th Georgia and bearing them forward, called uponhis officers and men to follow. Nobly and gallantly did they respond to thecall. Without flinching, the 14th advanced to meet the confident foeand by their well-directed volleys soon brought them to a stand. The ground wasnow hardly contested, but the deadly aim of the Georgia boys was toodestructive for Yankee ideas of personal safety and their lines began to waverthen gave way.

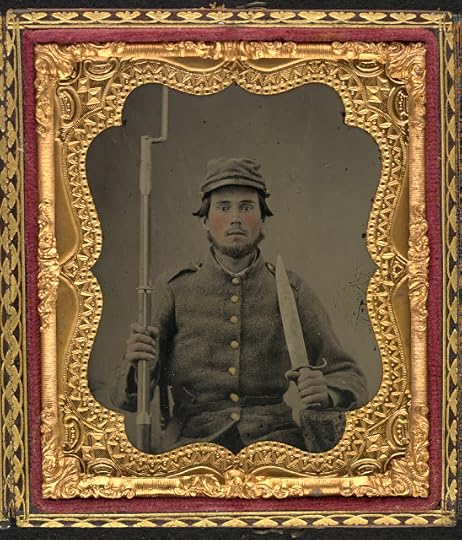

Private John Rigby of Co. D, 35th Georgia Infantry served in the same brigade as the 14th Georgia and fought alongside them at Cedar Mountain. He had been wounded at Mechanicsville during the Seven Days campaign and was later captured at the Wilderness. He died of acute bronchitis nearly a year later in Elmira, New York while still a prisoner of war.

Private John Rigby of Co. D, 35th Georgia Infantry served in the same brigade as the 14th Georgia and fought alongside them at Cedar Mountain. He had been wounded at Mechanicsville during the Seven Days campaign and was later captured at the Wilderness. He died of acute bronchitis nearly a year later in Elmira, New York while still a prisoner of war. They were closely followed upfor nearly a mile to where the route of the 14th crossed a road.Beyond this road was a small stream and beyond that a wheat field in which wasdrawn up a strong infantry force of the enemy. The road afforded our men anexcellent position from which they poured a most destructive fire into thelines of the enemy. Seeing the advantage and dreading the effects of our deadlyfire, one squadron of cavalry was sent out to drive us from the road. We sawthe cavalry advancing and without changing our position, we coolly awaitedtheir approach. When within 75-80 yards, Colonel Folsom gave the order to fireand down went horses and men by the score. Again, the valiant Yanks soughtsafety in hasty retreat and fled precipitately to the woods behind the wheatfield, closely followed by Georgia’s daring sons.

The regiment had advanced but ashort distance when Colonel Folsom fell from utter exhaustion. It was nownearly dark, the troops being much exhausted from the long march, hard fighting,and excessive heat. General Jackson though, under the circumstances, it wouldbe better to close the action for the night and accordingly pursuit of the flyingenemy was given up. They had been driven from the field and left hundreds oftheir dead and wounded behind. It was said by one of the generals who examinedthe filed that the 14th Georgia killed and wounded more men than itcarried into the field.

But it is not pretended that the14th Georgia was the only regiment in Colonel Thomas’s brigade thatacted gallantly. All did well. The 49th Georgia fired until they hadshot away their last cartridge. They then took what they could find on theYankees they had killed and afterwards charged the enemy with empty guns. The conductof the 35th Georgia and 45th Georgia is spoken of in themost flattering terms. It is said that this battle made the 24thtime that Colonel Thomas has been under fire. His conduct in action is characterizedby great coolness and unflinching bravery. It is understood that he hasreceived the appointment of brigadier general; the appointment is a good one.

The loss of the enemy isestimated at 1,700 killed and wounded plus 800 prisoners; our total loss was550. Our force engaged was about 14,000 men while that of the enemy was near30,000. The Yankees had one regiment busy all day burying their dead it isthough they did not get through. If our men had not been so exhausted and hadbeen able to follow up the enemy, there is no doubt the enemy would haveresulted in a complete rout. As it was, however, the victory was a decided oneand has added fresh laurels to the battle-worn heroes who so gallantly won it.

Source:

“Battle of Cedar Run,” from “Dixie,” an unknown soldier in the14th Georgia Infantry, Atlanta Southern Confederacy (Georgia),August 21, 1862, pg. 2

February 17, 2025

Miracle Makers: The 27th Illinois at Stones River

By any measure, the 27th Illinois had already performed a full day's work during their fighting south of the Wilkinson Pike on the morning of December 31, 1862 at Stones River. The regiment had helped repulse multiple Confederate attacks on their position and retreated by General Phil Sheridan's command around 11 a.m.

Moving north along the Nashville Pike in search of ammunition a few hours later, Major William Schmitt now commanding the regiment found himself in the presence of General Rosecrans. The commanding general of the Army of the Cumberland was in a tight spot and needed the 27th Illinois to help hold the line along the Nashville Pike. Schmitt replied that he was nearly out of ammunition but would use the bayonet. Rosecrans agreed and told him to go at the Rebels "quick, quick."

"After retreating over a mile, we struck the road running directly from Nashville to Murfreesboro where we halted and seeing the enemy coming to meet us, we were ordered to form in line of battle and hold the ground at all hazards," remembered Corporal William Lazenby of Co. K. "Major [William] Schmitt now being in command of the regiment reported that we were almost out of ammunition, but when that was gone, we were told to use the bayonet which proved most effectual. Our division still being in front, our brigade was ordered forward but we soon received a most deadly volley from the enemy which took great effect on our ranks, but at the same time, the order was given to charge and one continuous yell was given from our lines. Meeting the Rebels at the double quick, they turned about and we had the pleasure for once of seeing them skedaddle in good earnest. Following them so close under a heavy fire from us, we succeeded in taking a great many of them prisoners besides the killed and wounded."

Corporal Lazenby's description of what I'd like to call the Miracle at the 3-Mile Marker first saw publication in the February 12, 1863, edition of the Jacksonville Journal published in Jacksonville, Illinois.

Major William Schmitt took command of the 27th Illinois after Colonel Fazilo Harrington was mortally wounded during the regiment's fight near the Wilkinson Pike. Later that afternoon, he led the regiment in a counterattack that helped save the Federal position along the Nashville Pike that Corporal Lazenby describes below.

Major William Schmitt took command of the 27th Illinois after Colonel Fazilo Harrington was mortally wounded during the regiment's fight near the Wilkinson Pike. Later that afternoon, he led the regiment in a counterattack that helped save the Federal position along the Nashville Pike that Corporal Lazenby describes below. Camp near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

January 9, 1863

After acampaign of two weeks of marching and exposure to both wet and cold weather, weare once more in camp and have got our tents and hope for a short rest. As youhave doubtless heard all the particulars of the late battle, it would beuseless for me to attempt to give you any description of it even if I could. But,however, I will try to give you a partial account of our proceedings sinceleaving Camp Sheridan.

On the 26thof December, we received orders to march at daylight with five days of rations.After going about seven miles, we came in contact with the Rebel pickets on theNolensville Pike when a sharp skirmish took place, but the Rebels ran and wemarched on. As it was reported that a Rebel force was at Nolensville, we expectedto soon attack them but hearing of our approach, they left without causing usany trouble. After passing through the village, we encamped nearby but ourregiment was ordered on picket. The weather being cloudy, soon after dark itcommenced raining and rained hard all night. Of course, very little sleep wasenjoyed and having only one blanket each, we were all wet in the morning. Afterdrying them a short time by the fire, we again began our march and until 3 o’clockin the afternoon, we occasionally passed a few shots with the enemy who kept ashort distance ahead.

It havingrained most of the afternoon, we were again all wet and used the wet ground fora bed. However, we were allowed fire and during the night got some sleep. The nextmorning being Sunday, we were glad to learn that we were not to move.

The nextmorning opened upon us clear and pleasant. We were early under arms and on ourmarch. Having been traveling directly south, we here turned our course eastwardin the direction of Murfreesboro and traveled within about six miles of thatplace over very rough and stony roads and stopped for the night. The nextmorning [December 30] we were ordered out and after going about three and ahalf miles, we attacked the enemy with our skirmishers and all afternoonconstant firing was kept up by musketry which closed about sundown resulting inseveral being wounded but only two or three killed on our side and none in ourregiment.

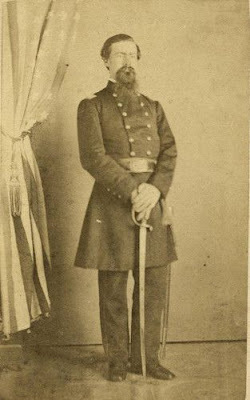

Colonel George Williamson Roberts, 42nd Illinois and commanding the brigade at Stones River was killed in action near the Wilkinson Pike on the morning of December 31, 1862.

Colonel George Williamson Roberts, 42nd Illinois and commanding the brigade at Stones River was killed in action near the Wilkinson Pike on the morning of December 31, 1862. We were assignedto General Sheridan’s division, the third, as was our brigade consisting offour Illinois regiments, viz. the 22nd, 27th, 42nd,and 51st, all commanding by Colonel G.W. Roberts of the 42nd.

Our brigadebeing in advance, we were ordered on Wednesday morning to open the battle andat daylight our sharpshooters were sent out and soon heard a continual firefrom musketry and increasing as it lasted. Soon our artillery was put intoposition and opened upon the enemy which was soon returned by them. In a shorttime, nothing could be distinctly heard but the roar of cannons and the rattleof musketry, the dead and dying seen laying in all directions around us.

The enemyworked more down to our right and having previously sent a strong force in thatdirection, doubtless with the intention of flanking our army, had themconcealed a short distance from our lines in front of Johnson’s division. Atdaylight they charged upon Johnson and although warned to be ready and have hismen in line, he failed to do so and allowed himself to be completely surprised.Out of his whole command, only one regiment was under arms. The others, withtheir equipment off and guns in stack, were carelessly getting breakfast whiletheir artillerymen were away getting water for their horses when the Rebelsmade a dash upon them. The men scattered in all directions and two regimentsdid not get their arms out of the stack. The Rebels took 16 pieces of artillerywithout even being once fired at. [Corporal Lazenby’s condemnation of Johnson’sdivision was a commonly expressed sentiment within the Army of the Cumberland.]

Gaining ourright wing, the enemy was soon in the rear of us and for over two hours we wereexposed to a terrible and destructive fire coming from our front and on bothsides. Our brigade was supporting Captain [Charles] Houghtaling’s battery andwas ordered to hold our ground, but his men were killed and wounded until therewere not enough men left to man the guns and we finally had to leave it but notuntil only one horse was left standing, all the others being shot down.

Captain Charles Houghtaling

Captain Charles HoughtalingBattery C, 1st Illinois Light Artillery

Being orderedto retreat, we fell back under a heavy fire and having gone a short distancethrough a dense forest of young cedars, we were met by General [James] Negleywho informed us that we were surrounded and must fight our way out. But beforethis, Colonel Roberts was killed and Colonel [Fazilo] Harrington severelywounded while supporting the battery.

Afterretreating over a mile, we struck the road running directly from Nashville toMurfreesboro where we halted and seeing the enemy coming to meet us, we wereordered to form in line of battle and hold the ground at all hazards. Major [William]Schmitt now being in command of the regiment reported that we were almost outof ammunition, but when that was gone, we were told to use the bayonet whichproved most effectual.

Our divisionstill being in front, our brigade was ordered forward but we soon received amost deadly volley from the enemy which took great effect on our ranks, but atthe same time, the order was given to charge and one continuous yell was givenfrom our lines. Meeting the Rebels at the double quick, they turned about andwe had the pleasure for once of seeing them skedaddle in good earnest.Following them so close under a heavy fire from us, we succeeded in taking agreat many of them prisoners besides the killed and wounded. We were now leftin undisputed possession of the ground. [To learn more about this action, checkout “Miracle at the Three-Mile Marker Now a Lake.”]

We lost onWednesday eight of our company, but none were killed that we know of. E.W.Ticknor, acting captain, was in command of our company throughout the fight anddid well as did every man under him. Although Co. K is but small, yet we haveas good fighting men in it as the nation affords. But not one desires to killif it was not necessary, but all feel the love of country and if necessary arewilling to lose their lives rather than see the government destroyed and ruledby traitors.

To learn more about Sheridan’s division at StonesRiver, please check out the following posts:

Surrounded by a Wall of Fire: With Sheridan’s Division at Stones River (22nd Illinois)

We Could Have Driven them to the Gulf: With the 42nd Illinois at Stones River (42nd Illinois)

Shoulder Arms! How Sheridan's and Davis's Divisions Were Armed at Stones River

Source:

Letter from Corporal William Lazenby, Co. K, 27thIllinois Volunteer Infantry, Jacksonville Journal (Illinois), February12, 1863

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

February 15, 2025

Like Spears of Grass Before the Flames: Charging Fort Donelson with the 14th Iowa

For future Congressman William H. Calkins, the sight at dawn on February 16, 1862, repaid manyfold the privations and sufferings he experienced during the days in front of Fort Donelson.

"The first gray streak of daylight displayed a white flag streaming from off the tops of the surrounding breastworks," he noted in a letter to the editors of the Lafayette Journal & Courier. "If you can imagine the feelings of our troops when they saw the rattlesnake flag fall and the glorious stars and stripes waving in triumph over the Rebel fort. It paid us tenfold for our suffering. To pay us for our gallant bravery, we had the honor to march in front of the long line of troops into the fort. General Floyd escaped as did General Pillow, but Generals Buckner, Johnson, and West were captured. There were from 10,000-12,000 prisoners taken and a rough-looking set I tell you."

A member of the 14th Iowa Infantry, Lieutenant Calkins' description of the victory at Fort Donelson first appeared in the February 22, 1862, edition of the Lafayette Journal & Courier published in Lafayette, Indiana.

First Lieutenant William H. Calkins, Co. H, 14th Iowa Volunteer Infantry went on to serve as regimental quartermaster of the 128th Indiana Infantry and major in the 12th Indiana Cavalry. After the war, he served four terms in Congress representing Indiana before moving to Washington Territory late in life. He died January 29, 1894, in Tacoma, Washington at age 51.

First Lieutenant William H. Calkins, Co. H, 14th Iowa Volunteer Infantry went on to serve as regimental quartermaster of the 128th Indiana Infantry and major in the 12th Indiana Cavalry. After the war, he served four terms in Congress representing Indiana before moving to Washington Territory late in life. He died January 29, 1894, in Tacoma, Washington at age 51. Fort Donelson, Tennessee

February 18, 1862

Editor Lafayette Courier, dear sir,

I do not wishto enroll myself among the many army correspondents or newspaper contributors,but as I am somewhat partial towards your excellent sheet, I though it wouldnot come amiss to give you the facts with regard to the battle and victory justgained by the brave boys of the western states.

It will befolly for me to undertake a description of the fort but suffice it to say thatit is admirably constructed and could have easily been made impregnable againstany number of troops. The attack was made on the fort by General Smith’sdivision on the 13th instant; Colonel Lauman’s brigade, composed ofthe 2nd, 7th, and 14th Iowa regiments and the25th Indiana was ordered to storm the southwest barricadement. Weadvanced from the summit of a hill on which we had encamped the night previousand had scarcely moved 100 yards when the batteries of the Rebels opened out adeadly fire of grape and canister from their entrenchments, however, thegallant soldiers were not to be daunted by a few missiles of death.

Onward we sped until we reached thefoot of the hill. Then we were ordered to halt and form the lines which werescattered and broken by the thick underbrush and timber which had been felledby the Rebels to impede our progress. We soon formed the lines and “onward” wasthe cry. We pushed forward until within about 100 yards of the entrenchment.The timber that had been felled by the Rebels proved effectual, for the largetrees fallen in all directions proved an insurmountable barrier for us, and theorder was given to halt and give them a few rounds from our muskets which wedid with telling effect. We completely kept them down behind the entrenchmentsand fought them five hours under a heavy fire from two batteries. The fallentimber proved quite advantageous for us; had it not been for this, we wouldhave been badly cut to pieces from the battery. And here suffer me to pronouncean encomium on the 25th Indiana: they suffered severely, being verymuch exposed, but they fought like heroes.

Colonel Jacob Lauman,

Colonel Jacob Lauman,Brigade Commander

When nightcame, we were ordered to fall back and encamp upon the ground where we campedthe previous night. The next day, our division was still, but on the extremeright, we heard heavy cannonading and musketry. And let me say here that neverin the annals of history was there a more severe contest that took place thandid on the right of the army. Floyd with his whole division came out of theirdens and attacked the Illinois brigade in General McClernand’s division. Floyd’sdivision numbered 7,000 strong, supported by 2,000 cavalrymen, making a totalof 9,000 men. The Illinois brigade was composed of four broken regiments, thetotal of the whole brigade did not exceed 2,500 men, odds of almost four toone.

The Rebelsadvanced and commenced the attack. Our brave boys drove them back with tremendousslaughter. Again, they advanced and were driven back with awful loss. A thirdtime, they railed and presented a different front, for they had learned theextent of our lines and outflanked us on the extreme right. Their cavalry madea rear attack at the instant they came up but, nothing daunted, our brave boysdrove them from their position, about faced, and charged on the Rebel cavalry,running them clear out of the state for they have not been heard of since. Ourammunition gave out and we were obliged to fall back. We were soon reinforcedby the Kentucky brigade and the Rebels were driven from their hiding places andwent back inside their breastworks in great confusion and disorder. Such as thescene of the second day.

The third daybeing the 15th instant, we found we had work to do yet. Orders cameto storm the breastworks of the enemy at all hazards. Colonel Lauman’s brigadewas selected for the work. We marched out a distance of a quarter of a milebelow the place where we first attempted the work. The division advanced; theyopened a deadly fire upon us and our boys fell like spears of grass before theflames. But soon the scene changed. Our boys mounted the works and over theywent. The Rebels fell thick and fast, but night set in and we were obliged toceased firing.

That night wastruly a night of suffering to us. It had rained and the mud in the ditches wasvery deep and we were obliged to lay in the mud beneath the canopy of heavenwhile the bombshells played around us like hail and terra firma froze beneath us.We thought of the happy ones at home and envied them their places. But morningcame and all was still. The first gray streak of daylight displayed a whiteflag streaming from off the tops of the surrounding breastworks. If you canimagine the feelings of our troops when they saw the rattlesnake flag fall andthe glorious stars and stripes waving in triumph over the Rebel fort. It paidus tenfold for our suffering. To pay us for our gallant bravery, we had thehonor to march in front of the long line of troops into the fort.

General Floydescaped as did General Pillow, but Generals Buckner, Johnson, and West werecaptured. I will not try to give you an estimate of the killed. One of theVirginia boys told me that his regiment numbered 800 and when they surrendered,they had 150 all told. There were from 10,000-12,000 prisoners taken and arough-looking set I tell you. Very soon, we will see New Orleans, but I mustclose.

To learn more about the charge of the Iowans at Fort Donelson, please check out this other post:

Buckeyes Among Hawkeyes : Ohioans at Fort Donelson with the 2nd Iowa

Source:

Letter from First Lieutenant William Henry Calkins, Co. H, 14thIowa Volunteer Infantry, Lafayette Journal & Courier (Indiana), February22, 1862, pg. 3

February 14, 2025

The Professor and the Comedienne: A Stones River Love Story

On Thursday, November 5, 1863, Captain Warren Parker Edgartonof Battery E of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery married the widower JuliaDaly Olwine in Nashville, Tennessee. It was apparently a quiet wedding- outsideof being recorded in the record of Davidson County, Tennessee marriages, nomention was made of the nuptials in any period newspapers. Wartime marriageswere hardly uncommon during the Civil War, but the circumstances of how aMassachusetts-born artillery officer from Ohio met one of the most beloved actresses ofthe American stage is history (quoting the History Guy) that deserves to be remembered.

To start, let’s introduce thecouple. Captain Edgarton is a familiar soldier to readers of the blog; thestory of how his battery was captured during the opening moments of the Battleof Stones River has been recounted in several previous posts. (See Comanche Versus the Professor, Receipt in Full in Red Ink, An Intimate View of Battery E's Demise, and Captured Entire) The captain wasborn May 16, 1836, in Harvard, Massachusetts, and by the age of 20 not only wasworking as a college professor but had published his first book. Moving toCleveland, Ohio in 1857, he continued his work in education while himselfstudying law and being admitted to the Cleveland bar in 1859. He gained anenviable reputation for his powerful oratory and a bright future as an attorneyand educator beckoned. Then the war came.

The couple: actress and comedienne Julia Daly and Captain Warren Parker Edgarton.

The couple: actress and comedienne Julia Daly and Captain Warren Parker Edgarton. Within days of the firing uponFort Sumter, Edgarton joined the Cleveland Light Artillery as a private and sawaction in the first “battle” of the Civil War at Philippi, Virginia in June.Upon returning from his 90-days’ service, Edgarton received a commission from GovernorWilliam Dennison to raise his own artillery battery. That battery becameBattery E of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery and by the end of 1861, itwas learning the ways of war among the hills of central Kentucky as part ofGeneral Don Carlos Buell’s Army of Ohio.

While Captain Edgarton drilled his men in Kentucky, Julia Daly won plaudits in city after city for her comedictalents and ability to command the stage like few others. Born in Pennsylvaniain 1837, Julia made her stage debut in 1855 and quickly developed a widefollowing as she toured the Northeast. Shestarred in a number of productions: as Caroline in Our Gal, as Biddy in IrishGirl in America, but perhaps most famously as Pamelia Appleby in OurFemale American Cousin. In another piece entitled In and Out of Place,Julia played upwards of 6 roles! Labeled as “lively and vivacious comedienne,” Juliatook her act across the ocean and made a big splash on the stages of GreatBritain and Scotland during the 1860 and 1861 seasons.

The winter of 1862 found herback in the states and as her future husband and his battery prepared to movesouth against Nashville in February 1862, Julia completed a highly successfulstand in Louisville, Kentucky. “We have never had an actress come among us socomparatively unheralded and yet achieve so great a hold upon the public favorfrom her very first appearance as Miss Julia Daly has done,” opined the LouisvilleDaily Courier. “We have surrendered at discretion and confess that she isthe very queen of the comic stage in spite of the parade of pretenders whowould arrogate that title. Her fun is infectious; she can be laughable withoutoverstepping the modesty of nature. She can sing beautifully and her acting isso thoroughly artistic. In fact, she never forgets that she is a lady performingto a refined and intelligent audience.”

In the meantime, CaptainEdgarton developed his reputation as one of the best artillery commanders inthe Army of Ohio. The “professor” put on a clinic on the evening of December30, 1862, as he deftly maneuvered his full battery into opening a surprise fireupon Captain Felix Robertson’s battery, battering Robertson so thoroughly thatthe Texan quickly withdrew. Despite this signal success, Captain Edgarton wasunable to persuade his brigade and division commanders to allow him to relocatehis battery (and the other two batteries of the division) to good defensive groundnorth along Gresham Lane. It doomed his battery to destruction the followingmorning.

Around 6:20 a.m. on December 31,1862, General John P. McCown’s Confederate division launched their dawn assaulton the Union right in the opening thrust of what became the Battle of StonesRiver. Edgarton’s battery, positioned near the intersection of Gresham Lanewith the Franklin Pike, took the brunt of that initial assault spearheaded bythe General Mathew D. Ector’s dismounted Texas cavalrymen. Edgarton’s gunnersmanaged to fire upwards of 20 rounds before being swiftly overwhelmed by Ector’sbrigade.

Adjutant Samuel Davis of the 77thPennsylvania witnessed Edgarton’s last moments on the battlefield that morning,watching breathlessly as Edgarton “grimly stood by one of his pieces andassisted by Lieutenant Berwick, loaded, and discharged it into the livingcolumn as it closed upon him, mowing a huge road through it and in an instantafter he was wounded. Many of his men refused to leave him and fought the foewith their swabs and were killed or captured.” Edgarton himself was shot in thegroin by a spent ball, and stumbling around one his guns, received two morewounds in the arm as he fell across the trail of the piece and was captured. Helater said, “I lost my guns, but I took the enemy’s receipt in full in red ink.”

Captain Edgarton spent about four months as a guest at "Hotel de Libby" along with several other Federal officers captured at Stones River. The poor fare and conditions broke Edgarton's constitution which eventually led to his resignation in July 1864.

Captain Edgarton spent about four months as a guest at "Hotel de Libby" along with several other Federal officers captured at Stones River. The poor fare and conditions broke Edgarton's constitution which eventually led to his resignation in July 1864. Captain Edgarton was among the38 captured Federal officers (including Brigadier General August Willich whowas captured mere moments after Edgarton) sent south as prisoners after thebattle. Passing through Chattanooga on January 3rd, the men were depositedin Atlanta and stayed for the better part of a month. In February, a group ofthem were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia where they would remainuntil exchanged in early May 1863. Edgarton received his exchange order on May8, 1863, a few days after the Battle of Chancellorsville, and arrived back in Clevelandon May 12th. Here is where a bit of supremely fortuitous timingbrought the professor and the comedienne together.

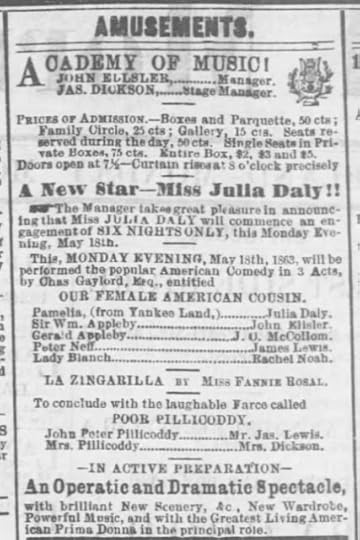

Clevelanders were eager to hearof Captain Edgarton’s novel experiences not only in the Battle of Stones Riverbut of life in “Dixie,” and he accommodated their desires by embarking on aspeaking tour. Before the war, Edgarton frequently provided oratory at theCleveland Academy of Music and he gave several talks there during this speaking tour. Itjust so happened that on Monday night, May 18, 1863, Julia Daly performed herfirst of six nights in Cleveland at the same Academy of Music, starring asPamelia in Our Female American Cousin. It was during this 6-day engagement thatI believe that Captain Edgarton and Julia met.

Now it is worth noting that atthe time, Julia was a recent widower. Before the war, she had married notedPhiladelphia attorney Isaac Wayne Olwine. Olwine was a gifted public speakerand author, like Edgarton, and had published a book about legal matters in the1850s before devoting himself fully to theatrical affairs. “He made noparticular mark as an actor, but became well known as a business agent, travelingagent, and subsequently stage manager of various theaters,” his obituarystated. Upon marrying Julia, Isaac “traveled with her on professional toursthroughout the United States and Great Britain. He devoted much of his time todramatizing works and has been agent abroad for some of the most popular piecesperformed in this country,” his obituary noted. He died of consumption inPhiladelphia on December 13, 1862, the same day as the Battle of Fredericksburg,leaving the entirety of his substantial estate to his wife Julia.

Advertisement from the May 18, 1863, edition of the Cleveland Morning Leader for "A New Star- Miss Julia Daly!" Captain Edgarton likely met his future wife sometime during this six night engagement. A romance blossomed that led to marriage that November in Nashville.

Advertisement from the May 18, 1863, edition of the Cleveland Morning Leader for "A New Star- Miss Julia Daly!" Captain Edgarton likely met his future wife sometime during this six night engagement. A romance blossomed that led to marriage that November in Nashville. One can only speculate exactly howthese two met, but the romance moved swiftly.Julia completed her engagement in Cleveland by late May, and likewise CaptainEdgarton moved back to the rejoin the Army of the Cumberland at roughly the sametime. There had been some changes made while he was gone; Battery E now wasassigned to the Post of Nashville and Edgarton found himself publicly criticizedby the commanding general William R. Rosecrans who called out Edgarton in hisofficial report of the Battle of Stones River.

“Captain Edgarton was guilty ofa grave error of taking even a part of his battery horses to water at anunreasonable hour and thereby losing his guns,” Rosecrans chided. As I argue in“Receipt in Full in Red Ink,” I think Rosey’s charges were hogwash and struckme as more an attempt to cover up for General Richard W. Johnson, a fellow WestPointer whose mistakes in deploying his division led to the disaster. It isworth noting that Rosecrans specifically requested Johnson to rejoin the armyin December after Johnson was captured near Gallatin, Tennessee in August. Johnsondisplaced the popular General Joshua Sill in command of the second division andSill would lose his life bravely fighting his brigade during Stones River; thatsaid, Rosey had a vested interest in protecting Johnson’s reputation from criticism.Not unsurprisingly, Edgarton took exception to Rosecrans’ charge, hotlydefending his record in his own after-action report that he wrote fromNashville on June 25. “As I have been charged with grave errors on the occasionof the battle, I respectfully request that I may be ordered before a court ofinquiry that my conduct may be investigated, Edgarton concluded.

He never got it. Rosecrans’ focuswas now on pushing the Confederates out of middle Tennessee and invadingGeorgia. Rehashing events from six months ago took a backseat to theoverarching object of combatting Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Denied achance to clear his name and left in the backwash of war, Edgarton and hisbattery remained in Nashville until early September when they were finallyordered forward, taking post at Stevenson and then Anderson’s Crossroads,protecting Rosey’s supply lines but not rejoining the main army.

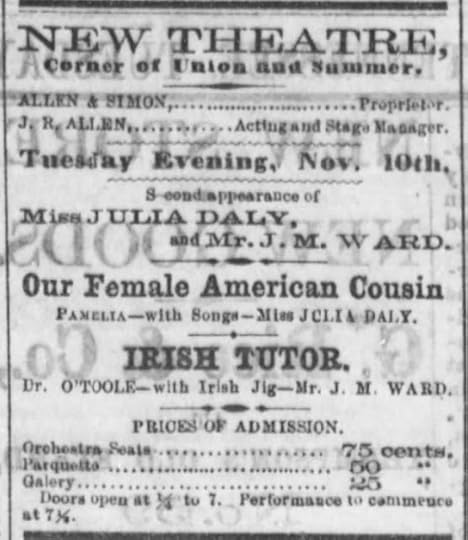

Advertisement in the November 10, 1863, Nashville Daily Union publicizing Julia Daly's stint at the New Theater located at Union and Summer streets in downtown Nashville.

Advertisement in the November 10, 1863, Nashville Daily Union publicizing Julia Daly's stint at the New Theater located at Union and Summer streets in downtown Nashville. One is left to wonder the exactlyhow, but Captain Edgarton secured a brief leave of command to travel back toNashville where on November 5, 1863, he married Julia Daly Olwine. Their timetogether must have been brief- Julia opened a series of engagements at the NewTheater in Nashville on November 9th and as for Captain Edgarton,with Rosecrans now relieved from command after Chickamauga, he was summoned backto the army by General Phil Sheridan who made him chief of artillery. Edgarton commandedthe guns at Fort Negley in Chattanooga and then played a role in the Federalvictory at Missionary Ridge. “Stationing two regular batteries on Orchard Knob,he directed their fire on the enemy until our own troops came in range, thenmounted his horse and dashed to the front, joining General Sheridan just intime to participate in the capture of Bragg’s headquarters,” a later biographyof Edgarton noted.

The couple would enjoy 23 years marriage,a time where the couple traveled extensively in Canada, Europe, and throughout theAmerican Midwest. Julia continued on the stage until giving her final Europeantour from 1870-1871. Captain Edgarton soon after joined the Post Department andwent on to a notable career as one of the best postal inspectors in the service.

Warren and Julia eventuallysettled in rural New Jersey on a farm they called Villa Rosello near Newfield. She passed away August 21, 1887, at the couple’shome, ending one of the most remarkable wartime romances that I’ve ever comeacross.

Life is full of what ifs but inthis case, had it not been for the fact that he was captured at Stones River, Idoubt that Captain Edgarton would ever have had the opportunity to meet Juliathat day in Cleveland in May 1863. That said, one could argue that the Battleof Stones River introduced Captain Warren Parker Edgarton to his wife.

I hope you’ve enjoyed taking thejourney with me.

February 11, 2025

Ready for more fighting if necessary: Freeman’s Ford to Chantilly with the 21st Georgia

The last week of August 1862 may have been the busiest in the history of the 21st Georgia Infantry's history during the Civil War. The Georgians fought in five separate engagements over the course of a little more than a week: Freeman's Ford on August 22nd, Manassas Station in the early morning hours of August 27th, Groveton on the evening of the 28th, Second Bull Run throughout August 29th and 30th, then Chantilly on September 1st.

The engagement at Groveton on the evening of August 28th against a portion of the Iron Brigade of the Army of the Potomac was a particularly hard fight for the regiment. "We carried 240 men into the engagement and advancing with our brigade, some became hotly engaged," one veteran recalled. "Onward we went to a fence, the enemy falling back before us. Whilst fighting here under a heavy crossfire, our regiment and the 21st North Carolina suffered unusually. Owing to some mistake, the 15th Alabama and 12th Georgia to our left were kept from firing and the enemy’s whole force became directed at us. Reinforced by the 26th Georgia and 61st Georgia of Lawton’s brigade, we charged across the fence, driving the enemy before us under appalling losses to ourselves. The enemy having retired to the woods and complete darkness now prevailing, we fell back to the fence when, after a few volleys, the firing ceased on both sides. Our loss on the memorable night of the 28th of August was very heavy as will be seen from the list of killed and wounded. We carried 240 men into the engagement and our wounded were so numerous that not more than a sixth of the regiment escaped unscathed."

This accountof the Second Manassas/Bull Run campaign, penned by an unknown soldier in the21st Georgia, first saw publication in the September 25, 1862,edition of the Atlanta Southern Confederacy.

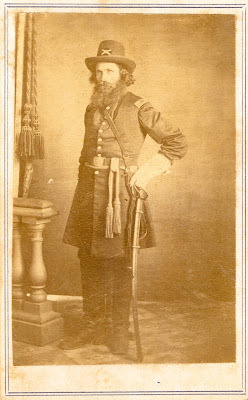

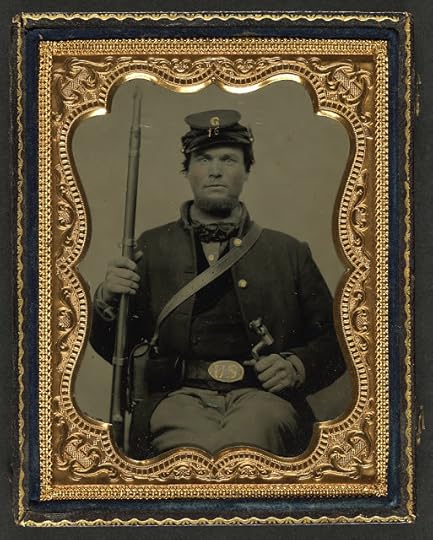

This image from the Liljenquist Collection depicts a private soldier wearing a Georgia state seal belt buckle.

This image from the Liljenquist Collection depicts a private soldier wearing a Georgia state seal belt buckle. Frederick City, Maryland

September 9, 1862

The numerousfriends of the 21st Georgia are doubtless anxious to know somethingof its engagements and losses in the recent battles and I propose to supplythis information to some extent.

We moved withour brigade (Trimble’s of Ewell’s division) from the Rapidan River when ourarmy under Lee commenced its forward movement and arrived at Freeman’s Ford onthe Hazel River. Here on the 22nd of August, we had a heavy skirmishwith the enemy who, in considerable force, had crossed and were about to attacksome portions of the army train. They had several brigades and a battery inposition.

Our brigade, consisting of the15th Alabama, 21st North Carolina, and our regiment underour gallant general, deployed skirmishers and advancing in line of battle, wedrove them over the river, killing and wounded a large number and causing themto fire their own trains on the other side. We killed, according to theirnewspaper accounts, the general commanding and, but for the river, would havecarried their battery. Having accomplished our purpose and having no artillery,we fell back to our original position. (To learn more about the fight atFreeman’s Ford from the Federal perspective, please check out “Standing LikePillars of Adamant: The 61st Ohio at Freeman’s Ford.”)

Next day we commenced the greatflank movement through Thoroughfare Gap and on the night of the 26th,after a toilsome march, arrived at Bristoe Station seven miles below and southof Manassas Junction where our division captured two trains of cars and manyprisoners. Already we had marched 20 miles that day but about 11 p.m. wecommenced a forced march to Manassas Junction in company with the 21stNorth Carolina, the two regiments under General Isaac Trimble. Arriving atManassas at 12:30 that night without cavalry or artillery support, and, findingthat the enemy was expecting us as their pickets fired into us, we formed inline and advanced into the village.

We had a short and quickengagement, the enemy opening on us with musketry and artillery. Fortunately,the darkness favored us and on we pushed, the 21st North Carolina onthe right and ours on the left. Becoming separated by a long line of cars, ourmovements were somewhat independent of each other. The conflict was short anddecisive. Our regiment took three pieces of artillery and some 50 prisoners inthe charge, including a lieutenant colonel, three captains, an adjutant, andthree lieutenants. The 21stNorth Carolina gallantly took two pieces of artillery during their charge. Animmense amount of stores, long trains loaded with goods of all kinds, sutler’sgoods, and supplies for Pope’s army all fell into our hands. This achievementwill ever be regarded by the 21st Georgia as one of its proudest.Our loss was very slight, considering the enemy had artillery in positionbesides their infantry.

We stood sleepless all night asthe campfires of the enemy were close around us and we learned from ourprisoners that they were in large force and much nearer us than our ownfriends. The sound of their artillery moving near us during the night alsoapprised us of our danger. It is attributable to darkness and their uttersurprise at our achievement that we were not attacked. Early the next morning,they were already advancing on us and shelling us when our division and theother troops arrived. We stood at rest in one of the old nooks and saw thebattle of that day including the magnificent cavalry fight between Stuart andthe enemy’s cavalry. (For a Federal perspective of that fight at ManassasJunction on August 27, 1862, please check out “Great Expectations Dashed: The Kanawha Division Meets the Army of the Potomac at Manassas Station.”)

Brigadier General Isaac R. Trimble was wounded in the leg August 29, 1862 during the first day's fighting at Second Bull Run. He would be wounded in the leg again 11 months later while taking part in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg. Trimble's wound was so severe that he was left behind at Gettysburg and spent the remainder of the conflict as a prisoner of war.

Brigadier General Isaac R. Trimble was wounded in the leg August 29, 1862 during the first day's fighting at Second Bull Run. He would be wounded in the leg again 11 months later while taking part in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg. Trimble's wound was so severe that he was left behind at Gettysburg and spent the remainder of the conflict as a prisoner of war. The next day, by crossing BullRun at the bridge and again at the Stone Bridge, we arrived near Groveton onthe identical ground where we drilled one year ago and at nightfall becameengaged with Milroy’s forces. We carried 240 men into the engagement and advancingwith our brigade, some became hotly engaged. Onward we went to a fence, theenemy falling back before us. Whilst fighting here under a heavy crossfire, ourregiment and the 21st North Carolina suffered unusually. Owing tosome mistake, the 15th Alabama and 12th Georgia to ourleft were kept from firing and the enemy’s whole force became directed at us.Reinforced by the 26th Georgia and 61st Georgia of Lawton’sbrigade, we charged across the fence, driving the enemy before us under appallinglosses to ourselves. Here Captain Buck Waddail [Joseph F. Waddail] fell deadwhile Lieutenant [Thomas F.] Attaway of Co. B fell mortally wounded. Amongstthe foremost slain was Lieutenant Adderhold of Co. A.

The enemy having retired to thewoods and complete darkness now prevailing, we fell back to the fence when,after a few volleys, the firing ceased on both sides. Our loss on the memorablenight of the 28th of August was very heavy as will be seen from thelist of killed and wounded. We carried 240 men into the engagement and ourwounded were so numerous that not more than a sixth of the regiment escapedunscathed. (To learn more about the fight at Groveton, please check out thesethree posts from the Iron Brigade: “How the Iron Brigade was Wrought" (2ndWisconsin), "A Baptism at Groveton" (19th Indiana), and “I Don’t Thirst for More Fight” (6th Wisconsin).

On the 29th, Major [ThomasC.] Glover, with the fragments of the regiment, fell into line and in theskirmish of the morning where General Trimble was wounded, he was present. Detailedin the afternoon to bury our dead, we were unengaged anymore that day. On the30th, we rejoined our brigade. Not numbering more than 40 men, wetook part in the brilliant success of that day and with our brigade sustainedand repelled the shock of three lines of battle thrown on our position withgreat energy and determination by the enemy. The dead on all the fields inwhich we had been engaged illustrates our fighting. At the close of this fight,the enemy was in full retreat. Our losses had been very heavy and most of theregiment was scattered in all directions, wounded and suffering for medicalattention. Major Glover was detailed by General Lawton as a physician to attendthem temporarily and leaving the command with Captain [William M.] Butt of Co.A, he went on his mission on the 31st.

The little command again movedwith the division to intercept the enemy between Centreville and Fairfax. NearChantilly, we were engaged again on the evening of September 1st.Our loss was not many, but the lamented Captain Butt fell here. Since then, wehave not been engaged but have crossed the Potomac and are now at Frederick,Maryland, a good deal recruited in numbers and ready for more fighting shouldit be necessary. Major Glover rejoined us at Leesburg.

Source:

Letter from unknown soldier in 21st GeorgiaInfantry, Atlanta Southern Confederacy (Georgia), September 25, 1862,pg. 2

February 9, 2025

Spoils of War: Trophies from First Murfreesboro

On Saturday morning July 26, 1862, the editors of the AtlantaSouthern Confederacy heard a ruckus in the streets and looking outdoors sawthat a large and visibly angry crowd had gathered in front of Hunnicutt &Taylor’s store. Hanging above the window was a “very large and handsome Lincolnflag,” the editors later remembered. “In full view from our window, spread tothe breeze waving to and fro was the beautiful flag of the once powerful andhonored, but now broken and disgraced, United States.”

The stars andstripes had not flown in Atlanta since January 1861 when Georgia became thefifth state to secede from the Union. And now this hated emblem floating in thecenter of Atlanta? Lieutenant Robert Graham, serving in Co. H of the 2ndGeorgia Cavalry, soon provided an explanation- the flag was the regimental flagof the 9th Michigan Infantry, captured during the recent engagementat Murfreesboro, Tennessee. The “rising wrath” of the crowd subsided once theysaw that the Union of the flag was down, and accepted Lieutenant Graham’sexplanation.

The editors ofthe Southern Confederacy ventured across the street to Hunnicutt &Taylor’s to examine the flag up close. “We found it to be a magnificenttrophy,” they noted. “It is the largest and handsomest flag we ever saw. It isof the finest silk, the brightest colors, and is most tastefully wrought- thestars and name of the regiment being in the most elegant needlework and the wholesurrounded by the finest silk fringe.”

A portion of a later flag carried by the 9th Michigan Infantry and now in the hands of the Michigan State Capitol. The location of the original flag described in this article is unknown.

A portion of a later flag carried by the 9th Michigan Infantry and now in the hands of the Michigan State Capitol. The location of the original flag described in this article is unknown. LieutenantGraham brought several trophies home from the battle besides the flag, including the brigadiergeneral epaulettes that belonged to General William W. Duffield and two captains’swords, one of which belonged to Captain Oliver C. Rounds who commanded CompanyB of the 9th Michigan. “It is of the most elegant workmanship andfinish; we never saw a service sword that was more beautiful,” the editorsgushed. “It had on it this inscription: ‘Presented to O.C. Rounds, Captain,Chandler Guards, 9th Regiment, Mich., by his friends of Niles,Michigan.”

While the editorsmay have gushed about his beautiful sword, they had a much less favorable viewof Captain Rounds. As it turns out, Captain Rounds was the provost marshal inMurfreesboro at the time of Forrest’s attack on July 13, 1862. While hisCompany B fought the 2nd Georgia Cavalry at the Rutherford CountyCourthouse (see “Charging the Rutherford County Courthouse”), Lieutenant Grahamclaimed that Captain Rounds was found hiding under the bed of his bride to be at ahome in Murfreesboro.

The young woman he was courtingwas Corine Reeves who lived in the mansion of her grandmother Katherine Reeves.The Reeves family were known for their Union sympathies and offered room andboard to Federal officers, including Rounds’ commanding officer LieutenantColonel John G. Parkhurst. Parkhurst himself was courting Corine’s older sister Josephine in July 1862. The editors ofthe Confederacy would perhaps be scandalized (but not surprised) tolearn that while Captain Rounds was wooing Corine, he already had a wife in Michigan! [The 1860 censusstates that Rounds was living in Niles, Michigan with his wife Sarah; theyremained married and are buried together at Inglewood Park near Los Angeles, California.]

All that aside, as the Confederacyreported it, Captain Rounds was due to marry Corine on the evening of July 13th.The wedding day certainly didn’t go according to plan. After taking the courthouse in the center of town, Confederate detachments spread throughout the city to capture other members of the garrison. Lieutenant Grahamlearned from local residents that Rounds was staying in the Reeves’ mansion and“went to the house where he was met by the captain’s intended wife, who, inanswer to his inquiries, assured him that Captain Rounds was not in the house.”Reeves’ neighbors, watching this, assured Graham that Rounds was indeed in thehouse, so the Georgian entered the house to investigate for himself. “He soondiscovered him under the bed and, seizing him by the foot, dragged him out andreceived from him his sword."

The current locations of both the 9thMichigan flag and Captain Rounds’ sword are unknown.Sources:

“A Union Flag Displayed in Atlanta,” Atlanta SouthernConfederacy (Georgia), July 27, 1862, pg. 3

John Gibson Parkhurst Collection, Michigan State University, https://d.lib.msu.edu/cwc-jgparkhurst

February 8, 2025

Charging the Rutherford County Courthouse

On the morning of July 13, 1862, a cavalry command underColonel Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked and compelled the surrender of theFederal garrison at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Among those taking part in theassault was Private John C. Ellington of the 2nd Georgia Cavalry whoin this brief letter to his father back home in Jonesboro described how hiscompany, the Clayton Dragoons, took the Rutherford County Courthouse.

“The enemykept up a continual crossfire from the windows,” Ellington stated. “We wereordered to charge on foot. At the first effort, they poured a volley of ballsinto our ranks, killing R.S. Henderson and F.M. Farris while severely woundingD.P. Morris and Robert Payne, all men from the Clayton Dragoons. We got an axeand charged from another corner and succeeded in reaching the courthouse andbroke down the door. About this time, all of them went to the upper story so wewent in and built a fire. This they could not stand and they surrendered atonce- 56 in number.”

Ellington’saccount of the First Battle of Murfreesboro first saw publication in the August10, 1862, edition of the Atlanta Southern Confederacy.

The Rutherford County Courthouse survived the war and was the scene of countless important events during the conflict. Besides the fight between Co. B of the 9th Michigan Infantry and the 2nd Georgia Cavalry during Forrest's attack in July, the courthouse also briefly held the prisoners John H. Morgan's command took at Hartsville in December 1862 and was used as a holding ground for Federal prisoners captured during the Battle of Stones River. It later served as headquarters for the provost marshal during the years of Federal occupation after Stones River.

The Rutherford County Courthouse survived the war and was the scene of countless important events during the conflict. Besides the fight between Co. B of the 9th Michigan Infantry and the 2nd Georgia Cavalry during Forrest's attack in July, the courthouse also briefly held the prisoners John H. Morgan's command took at Hartsville in December 1862 and was used as a holding ground for Federal prisoners captured during the Battle of Stones River. It later served as headquarters for the provost marshal during the years of Federal occupation after Stones River. Dear Father,

At 2 p.m. on the12th instant, we were ordered to start with two days’ rations butwhere to we knew not. At the sound of the bugle, we took up the line, passedthrough McMinnville and on towards Murfreesboro. At 1 o’clock at night we arrivedat Woodville [Woodbury], stopped one hour, and then on we went. About the crackof day, we were halted four miles from Murfreesboro and ordered to load and capour guns. All were ready in a few minutes.

From here totown we went like a thunderstorm, riding almost as fast as our horses couldrun. We entered town at good light and were greeted by 1,500 of the enemy. Theball was opened at once by a company that was in the courthouse. The TexasRangers were in front and passed on towards the camp of the enemy. We werehalted and ordered to take the courthouse; this we did though at a dear price.

The enemy keptup a continual crossfire from the windows. We were ordered to charge on foot.At the first effort, they poured a volley of balls into our ranks, killing R.S.Henderson and F.M. Farris while severely wounding D.P. Morris and Robert Payne,all men from the Clayton Dragoons. We got an axe and charged from anothercorner and succeeded in reaching the courthouse and broke down the door. Aboutthis time, all of them went to the upper story so we went in and built a fire.This they could not stand and they surrendered at once- 56 in number. [This was Co. B of the 9th Michigan Infantry; Bennett's history of the 9th Michigan says that 42 men of the company surrendered, not 56.] We nextarrested General George Crittenden and staff at a private house without firinga gun. We also arrested a great many others who were scattered over town. I saw15 men shot down in the courthouse square. We had no artillery or infantry. Afteralmost five hours, we captured the whole army except a few who scattered off.

We then burntthe depot, some cars, and a large amount of commissary stores. The propertytaken and destroyed is supposed to be worth $2 million.

The Rutherford County Courthouse survived the warand stands today as the centerpiece of a bustling downtown Murfreesboro,Tennessee. The first floor of the courthouse is open to the public and featuresa small museum explaining some of the history of the courthouse and ofRutherford County. In 2002 during the restoration of the courthouse, a firedLorenz bullet was discovered atop one of the columns, possibly a relic fromthis assault on the courthouse on the morning of July 13, 1862.

Source:

Letter from Private John C. Ellington, Co. F, 2ndGeorgia Cavalry, Atlanta Southern Confederacy (Georgia), August 10,1862, pg. 2

February 2, 2025

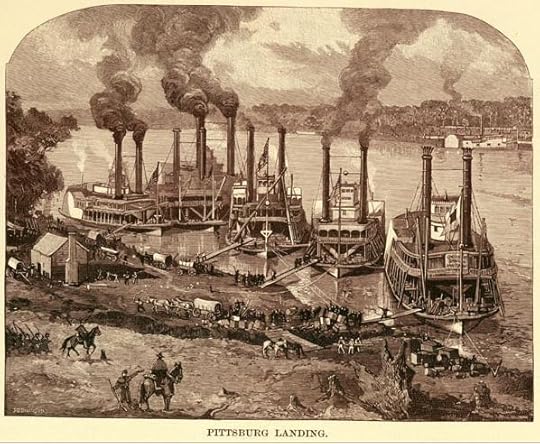

Chaplain Livermore’s Rough Sunday at Pittsburg Landing

Chaplain Lark S. Livermore of the 16th Wisconsin had already endured a Sabbath unlike any he'd ever experienced before when on the afternoon of April 6, 1862, he witnessed the frightening breakdown in morale amongst his comrades in the Federal army.

He was starting to dress the wounded arm of his colonel when "a few shells from the enemy dropped amid the promiscuous crowd of thousands on the bank and got up a regular stampede. The whole side hill seemed in motion, making a break for the boats which began just then (as all had steam up) to back off from shore amid the deafening cry, ‘the Rebels are upon us!’ The backing off of the boats heightened the alarm. I handed the Dr. Torry the bowl I was using to catch the blood from the arm of Colonel Allen, fearing for the safety of Charlie with the horses on shore in such an alarming stampede. The gangplank was literally hemmed full and men crowded off into the river in a rush to get on board the boats and away from the advancing foe. The boat backed off just as I came on to the gang and met the rushing crowd and let the gangplank fall into the river. I then thought it was each man for himself and acted accordingly, literally making a bridge of the heads and shoulders of those crowding the gang. I made my way to shore, getting wet only to the top of one bootleg."

Chaplain Livermore's lengthy account of Shiloh, written over the course of nearly two weeks, provides one of the finest descriptions I've yet seen of the chaos of the fighting on April 6th, and speaks to the experience of many Federal regiments that would fight, break, reform, and fight again in position after position throughout that fateful day. This account was constructed by combining Livermore's two accounts of Shiloh published in the Berlin City Courant; one published May 15, 1862 which covers the retreat up until the point he is ordered to the boats, and the second on July 10, 1862 which covers his experiences at Pittsburg Landing among the wounded.

Private Horace H. Smith of Co. G of the 16th Wisconsin Infantry was among Chaplain Livermore's comrades at the Battle of Shiloh. At Shiloh, the regiment's first engagement, the 16th Wisconsin suffered a loss of 245 men killed, wounded, and missing.

Private Horace H. Smith of Co. G of the 16th Wisconsin Infantry was among Chaplain Livermore's comrades at the Battle of Shiloh. At Shiloh, the regiment's first engagement, the 16th Wisconsin suffered a loss of 245 men killed, wounded, and missing. Camp Prentiss, Tennessee

April 18, 26, and 29, 1862

Long ere thiswill reach you, you will have seen and published many versions of our terriblebattle of the 6th instant. But as there are certain items of localinterest to your readers, I will write a brief account as it passed under myown observation.

It was a fair,bright morning and I was going down to the tent of the brass band to give themthe hymns to sing at service at 10 o’clock and met one of our pickets, drivenin by the enemy then not a mile distant from our encampment. As yet at 7 o’clocka.m., none but the earliest risers had been to breakfast and many of theofficers were not up even. General Prentiss’s aide came dashing down on hisfiery steed and ordered all to fall into line of battle. Four of the companies(A, B, C, and D) had been sent out on picket duty to the right of our frontleaving the 16th Wisconsin, 18th Missouri, 61stIllinois, and 18th Wisconsin unpicketed entirely or nearly so,General Prentiss simply saying as I learn by the 18th ‘boys, guardyourselves well in front.’

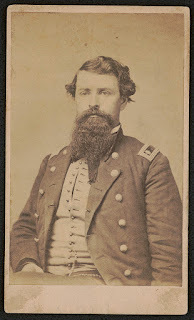

General Benjamin M. Prentiss would be captured later in the day on April 6, 1862 along with about 2,500 men from his division and that of General W.H.L. Wallace.

General Benjamin M. Prentiss would be captured later in the day on April 6, 1862 along with about 2,500 men from his division and that of General W.H.L. Wallace. That a general, whoseheadquarters was not half a mile from where he was first fired at by the enemyshould so leave raw troops (the 18th Wisconsin left the boatSaturday night) and that, too, when from Friday night (so says camp rumor) afight was expected. When I think of the cords of arms, legs, and skulls, not tothink of the thousands of bodies that swell a soldier’s grave, not to speak ofthe innumerable groans and sighs of widows and orphans and the bethrothed ones,words are no images for feelings.

The long roll sounded and in 15minutes, Colonel Benjamin Allen and Lieutenant Cassius Colonel Fairchild wereat the head of the noble 16th Wisconsin, leading them to face theapproaching foe. Adjutant [George M.] Sabin and I mounted our horses togetherand were soon up with our brave boys, for we had not to ride over 800 yards. Anhour before this, those four companies (A, B, C, and D) had met the pickets atour right, skulked in ambush, and received their scattering fire. Here fell,almost at the first fire, our dear friend and most ardently loved Captain EdwardSaxe, shot through the heart. No lingering, tortured death was his. Here alsoin this skirmish Sergeant John H. Williams was shot in the throat or a littleto one side, and the ball came out at the center of the back of his head. Thepoor fellow said, “I am mortally wounded, loosen my belt.” One more breath and allwas over; the spirit left the body.

Both were borne back to CaptainSaxe’s tent and laid like brothers or twins in death, side by side on thecaptain’s pallet. They had fought side by side, having been ordered to joinColonel Moore and take the right flank. They now sleep in death side by side.On Tuesday they were buried by our boys. Their watches, money, and even theirboots were taken by the enemy. They now lie encircled by three trees 18-inchesthrough at the stump, cut off 60 feet high by cannon balls and the topspitching towards their graves as if to do them reverence. Future generationswill mark the spot where they sleep for these oaks will sprout again to standas living sentinels over the dead.

In this picket engagement, ColeySmith, the orderly of Co. A, was dangerously wounded in the shoulder and is nowat Savannah, the ball not extracted. The company deeply feels his loss; he isthe best drill officer in the regiment, a man beloved by all and from hismilitary tact commanded the respect of all. [Orderly Sergeant Smith would dieof his wounds one month later at Keokuk, Iowa, having received a fieldcommission as first lieutenant.]

Now I must describe the openingfire on our front. The 16th Wisconsin passed the open field andformed in line in the thick brush of the parade or review ground of Saturday.Colonel Allen, with characteristic coolness, was cheering his men to nobledeeds, saying to them, ‘now be deliberate and pick your man.’ General Prentissrode by in great haste; I approached him myself and said, ‘Now general, ifthere is anything I can do, call on me.’ He said, ‘Put spurs to your horse and goto my headquarters and tell my aides all are relieved... (this portion of thetext is unreadable unfortunately). I say if honor it could be to carry a dispatchfor a general who would allow himself to be surprised by the enemy in solidcolumn not 800 yards from his headquarters. On my return to him, all was stillmore excited. A small battery came thundering down to our aide as we hoped.

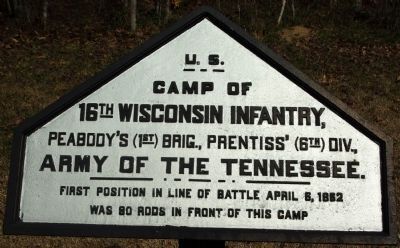

Camp marker for 16th Wisconsin at Shiloh National Battlefield.

Camp marker for 16th Wisconsin at Shiloh National Battlefield. The firing to our right waswaxing warm and Prentiss ordered Colonel Allen and the battery to file rightand march where the firing was warmest. At this juncture, I cast my eye to theleft and perhaps 100 yards off there stood the Secesh army (having risen fromthe ground) with fiery red flag in full view. I rode right up to General Prentissand signaled him to behold the secesh and flag. Colonel Allen also saw them andcited the general that way. From this moment, there was a perfect hailstorm ofbullets. General Prentiss, having ordered the battery to halt, now directed itto ‘file left and fire.’

As this volley was exchanged, Isaw Charlie [his 12-year-old son Charles B. Livermore] and old Kate some 75yards off coming in haste. I rode to him and found he only wished to be with me;I sent him to the tent as he could do no good. Now our boys formed a line thefurther side of the open field and exchanged shots in the thick brush with thefoe. Governor Harvey, when here, went out to this point and saw how the brushwas literally mowed down. He said it ‘seemed as wonder that a single man livedthrough it.’

General Prentiss ordered us tofall back to the trees 25-30 rods across a cleared field ‘in double quick time.’Colonel Fairchild would not repeat the order. He heard it but told the boys tofire again. They delighted to obey his order. But one of Prentiss’s aides camedashing along the whole line, ordered a retreat to the open timber and to firefrom behind the trees. The enemy was advancing by brigades in column threedeep. These are the circumstances under which we retreated. Some of theprisoners taken said they all believed us sharpshooters. Our Belgian rifles,such was the proximity of the armies, would send a ball through their columnthree men deep.

Lt. Col. Cassius Fairchild, 16th Wisconsin

Lt. Col. Cassius Fairchild, 16th WisconsinWounded at Shiloh