Jason Y. Ng's Blog, page 7

August 19, 2014

Pint-sized Heroes 未夠秤

They used to live in the same residential complex, attend the same school and ride the same bus every morning. They both grew up in devout Christian families and were taught to take an interest in society.

But 17-year-old Joshua Wong Chi-fung (黃之鋒) and 20-year-old Ma Wan-ki (馬雲祺) – better known as Ma Jai (馬仔) – can’t be more different from each other. Joshua is a household name and his spectacled face has appeared on every magazine cover. He is self-assured, media savvy and can slice you up with his words. Ma Jai? Not so much. He gets tongue-tied behind the microphone and fidgety in front of the camera. He is a foot soldier who gets up at the crack of dawn to set up street booths and spends all day handing out flyers for someone else’s election campaign.

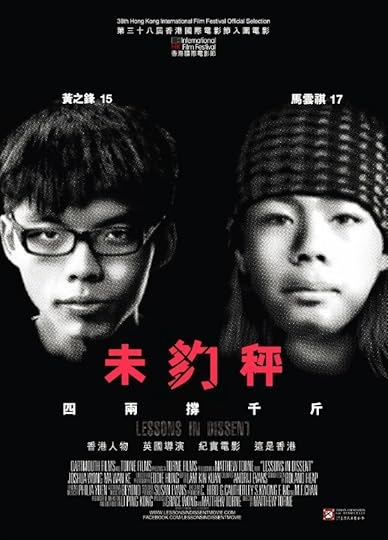

Lessons in Dissent by Matthew Torne

Lessons in Dissent by Matthew TorneThe two young men were the subject of a recent documentary by first time British director Matthew Torne. Lessons in Dissent (《未夠秤》), an official selection at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival, centers around the “Moral and National Education” (MNE) controversy in 2012 that drew hundreds of thousands of protestors to the streets. The watershed moment jolted citizens out of their political apathy and taught them that social movements, if properly run, can bring about real policy changes. For if it weren’t for activists like Joshua and Ma Jai, students today would have been sitting in MNE classes and learning how to praise the Communist Party and why they should guard against Western-style democracy.

Boy wonder

Joshua is a pint-sized force of nature to reckon with. He was just 14 when he founded Scholarism (學民思潮) to promote civic participation among the youths. In the fateful summer of 2012, the self-described “middle class kid” mobilized scores of like-minded teenagers and staged a nine-day sit-in and hungry strike at the government headquarters demanding MNE be scrapped. It was his charisma and tenacity that captured the imagination of his peers, inspired many more and eventually cowered C.Y. Leung into retracting the curriculum. Since then, the 17-year-old has been using his new-found fame to fight an even bigger cause: universal suffrage. In the recent Occupy Central poll on electoral reform, Scholarism and its ally, the Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS; 學聯) put forward one of the three proposals on the ballot. Over 300,000 citizens (nearly 40% of those who voted) sided with the students in the end. There is little doubt that Joshua has already earned a seat at the table next to heavyweights like Anson Chan, Benny Tai and Emily Lau.

Joshua Wong takes the lead

Joshua Wong takes the leadJoshua loves the media, and the media love him even more. On any given day, the school boy may start the morning with a telephone interview with The Times, meet the camera crew of a Dutch television network before lunch and finish a 1,500-word op-ed piece for The Apple Daily by sundown. He carries an iPad to keep track of his back-to-back appointments and taps his stylus on the smart phone screen at a frightening speed. While his friends are busy playing video games, Joshua is debunking political myths on radio talk shows or challenging the establishment on televised debates. “I was in Form 2 [eighth grade] when I started. No one else has ever done what I did.” said Joshua. It wasn’t arrogance; it’s simply a fact. The teenage boy is a prodigy, a savant and a Hollywood child star wrapped into one.

But there is always something sad about Hollywood child stars. All that media exposure has taken away Joshua’s adolescence and his chance at a normal life. He runs on so much adrenaline that he comes off as robotic, if not altogether possessed. Being a public figure has also hurt his public exam results and dashed his hopes to attend a more sought-after university. Notwithstanding these sacrifices, he wouldn’t have it any other way. “So far the benefits have outweighed the costs,” he explained. “I’ve experienced so much and made so many connections within a very short time.” Still, fame can be a double-edged sword. Joshua feels the weight of the city on his shoulders, and that the future of democracy depends on him. Although not a big Spider-man fan, he remembers what Uncle Ben told Peter Parker about power and responsibility.

In a few weeks, Joshua will begin his freshman year at Open University. When asked if he was excited about starting a new chapter, he shrugged, “I don’t think I’ll be going to class much.” Here’s why. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (全國人大) will convene in Beijing next week to discuss, among other things, the nomination procedure for the 2017 chief executive election. Whatever conclusion reached by the Standing Committee is expected to involve some mechanics to pre-screen candidates. As soon as Beijing throws down the gauntlet, Scholarism and the HKFS will fire the first shot of the Occupy Central movement by staging a student strike across all ten universities in the city. “We need to respond swiftly with action. Civil disobedience is the only means to achieving full democracy,” said Joshua, sounding more like Mahatma Gandhi than a freshman-in-waiting.

The media love him

The media love himThe other kid

Ma Jai was 16 when he was bitten by the social activism bug. In January 2010, he joined hundreds of students to besiege the Legislative Council to protest against the cross-border high speed rail link (廣深港高速鐵路), a wasteful pork barrel project that threatened to displace thousands of villagers in the New Territories. The movement opened his eyes to social injustice and political oppression. Armed with a new sense of purpose, the high school drop-out joined the League of Social Democrats (LSD; 社民線) – LongHair’s party – in 2011 and has been working there as a campaigner ever since.

Ma Jai represents the vast majority of social activists who work quietly behind the scenes. A typical day involves making banners and placards, phoning up social organizations and notifying reporters about upcoming events. He and his fellow LSD staff go in and out of courtrooms and police stations like they were public parks. If he isn’t bailing out another party member, he’ll be giving a statement to the police for an alleged illegal assembly. The work isn’t glamorous, but someone’s got to do it. That’s why Ma Jai felt uneasy about sharing top billing with Joshua in the British documentary. “I’m not famous and I don’t want to be famous,” he said. “I am just a cog in the wheel.”

Ma Jai is used to arrests

Ma Jai is used to arrestsBut activism isn’t only about banners and telephone calls. In 2013, Ma Jai was arrested for desecrating the city’s flag – a criminal offense in Hong Kong – and spent two days in a holding cell while waiting for an arraignment. He has had other brushes with the law. “I have two criminal records. Or is it three?” he couldn’t tell me for sure. Like a true revolutionary, he shrugs off convictions and considers them a badge of honor. He wears Che Guevara on his chest and has Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky on his lips. And when he is not fighting for universal suffrage or an old age pension scheme for all, he is speaking out for foreign domestic workers and new immigrants from Mainland China – groups that have long been considered politically toxic. “That’s why I belong here with LSD. We don’t compromise our beliefs for votes,” he said.

As for Occupy Central, Ma Jai and his comrades are ready for battle. All hands are now on deck to back up Scholarism’s citywide student strike in September and to occupy the financial district as early as October. Despite its reputation for being a lone wolf, LSD has little choice but to take its cue from other political parties. “We are not big enough to occupy Central on our own,” Ma Jai admitted. “We are counting on the rest of the pan-democrats to do the right thing.” He heaved a sigh, as he rolled a cigarette from a pouch of loose tobacco and lit it up.

* * *

Happy to be in the background

Happy to be in the backgroundI attended a screening of Lessons in Dissent at the Hong Kong Art Centre last Thursday. During the Q&A session after the show, one of the members of the audience shared her reaction to the film. For future screenings of Lessons in Dissent, visit www.facebook.com/lessonsindissentmovie.

Post-film Q&A session

Post-film Q&A session

Published on August 19, 2014 20:57

July 17, 2014

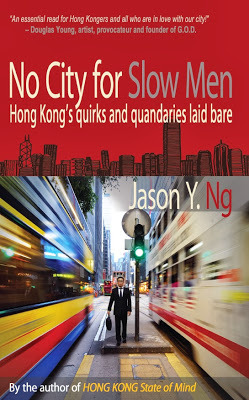

Join the Club 入會須知

You have reached a midlife plateau. You have everything you thought you wanted: a happy family, a well-located apartment and a cushy management job. The only thing missing from that bourgeois utopia is a bit of oomph, a bit of recognition that you have played by the rules and done all right. A Porsche 911? Too clichéd. A rose gold Rolex? Got that last Christmas. An extramarital affair that ends in a costly divorce or a boiled bunny? No thanks. How about a membership at one of the city’s country clubs where accomplished individuals like yourself hang out in plaid pants and flat caps? Sounds great, but you’d better get in line.

Always a good sign

Always a good signClubs are an age-old concept that traces back to the Ancient Greeks and Romans. The introduction of coffee beans to England in the mid-17th Century spurred the proliferation of coffeehouses for like-minded gentlemen to trade gossip about the monarchy over a hot beverage. In the centuries since, these semi-secret hideouts evolved into main street establishments that catered to different social cliques based on a common profession or pastime. The idea then spread across the English-speaking world, from the British Isles to colonies like America, Australia, India and that tiny speck of land on the south coast of China that would go on to become a shining beacon of capitalism.

In Hong Kong, a place where status is gold and exclusivity is king, private clubs are as much a vestige of our colonial days as they are a symbol of success. Many expat communities have long planted their flags on the city’s prime real estate, with the American Club in Central, the Japanese Club in Causeway Bay and the Indian Club in Tai Hang. For a decidedly unathletic city, we have a full suite of sports clubs, from golf and yachting, to football, cricket and rugby. There is also a growing number of members-only restaurants like the China Club, the Kee Club and the unmistakably Victorian Chariot Club.

The American Club has a country club house in Tai Tam

The American Club has a country club house in Tai Tam While the city’s affluence has grown significantly in the last half century, the number of club memberships hasn’t. The waiting lists to get into the more prestigious clubs are measured in years, sometimes decades. Since most clubs require referrals from existing members, applicants are known to weave intricate webs of social connection to befriend the right people to secure a sponsorship. Sometimes they go a step too far. Last year, two gentlemen went from the clubhouse to the big house, from sitting at the bar to sitting behind bars, after they were caught bribing long-time members of the Hong Kong Jockey Club to lie about the length of their acquaintanceship.

But this is Hong Kong after all, which means there is always a way to skip the line so long as you are willing

The prestigious Aberdeen Marina Club

The prestigious Aberdeen Marina ClubIf you wonder what it is about these private clubs that make people pay a fortune – sometimes risk prison – to get in, then look no further than the famous 80s sitcom theme song that sums it up for you: sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name. Indeed, there is something inherently comforting and almost narcotic about hearing someone say "Welcome back, Mr./Ms. [Insert your surname here]." In the developed world, members-only clubs are the last bastion of English aristocracy. They are one of the very few places in the middle class milieu where respect and camaraderie can be bought and sold, and where you are greeted as if you were all four Beatles on a reunion tour each time you walk through the guarded doors.

But Hong Kong is also a pragmatic city. The costs and benefits of every investment are carefully weighed, especially for a big ticket item like club memberships. Even the deep-pocketed would be hard pressed to shell out millions just to feel like Norm in Cheers. For bankers and insurance agents who have their eyes on the big fish, it is all about the networking. The Aberdeen Marina Club, for instance, is where property tycoons like the Lees, the Hos and the Kwoks rub elbows and chug down a pint at one of the four in-house restaurants. Or so I heard from Rich, who used to spend his weekends there with his parents until he hawked his membership for a vacation home in Phuket. “Very few members actually own a boat at the club,” my friend observed. Rich is right: who gives a flip about sailing when A-list celebs are lying around like red meat in a shark tank? And who fusses over the seven-figure joining fee when you can earn many times more in future business?

Where everybody knows your name

Where everybody knows your nameThe quintessential human nature to want to belong – and to move in circles beyond one’s reach – is what makes private clubs irresistible. If you look hard enough, however, you will notice that this club mentality has already seeped into mainstream society. Hotels, airlines, credit cards and even cell phone manufacturers (Vertu comes to mind) have long rebranded themselves into members-only clubs, offering concierge services, lounge access and other VIP benefits that are designed to make outsiders feel left out, like the kid who wants a train set but gets a sweater on Christmas Day. To dumb it down for the masses, these programmes are often tiered – silver, gold, platinum and super duper titanium – so that social climbers can see the progress they have made and the distance left to go.

From the Jockey Club to the Diners Club, the golf club to the alumni club, memberships confer status, cache, and if it all works out, business opportunities and upward mobility. While a segment of society continues to fight head over heels to get a foot in the door, it is perhaps instructive to point out that there is one club so exclusive and so one-of-a-kind whose membership no amount of money or social connection can buy, and yet it requires no application form, no referral and no joining fee. If only we take a step back to see the forest for the trees, we will realize that the ultimate club is the one that each of us is born into: our own family. It may not be much of a status symbol in the conventional sense, but its membership is more selective, fulfilling and useful than what any brick-and-mortar private club can ever offer.

The world's most exclusive club

The world's most exclusive club* * *

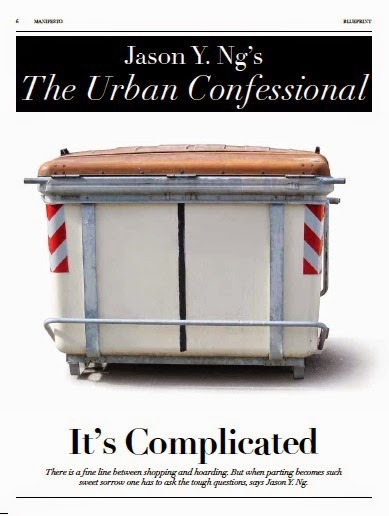

This article previously appeared in the July/August 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column "The Urban Confessional."

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

Published on July 17, 2014 01:00

July 15, 2014

An Okay Performance 不過不失的一埸

The World Cup is over. Finished. The End.

Now that the soccer circus has left town and the blare of the vuvuzela is no longer ringing in our ears, we can’t help but feel a little lost. I am not talking about that sense of emptiness we get when something spectacular has finally come to an end, like finishing a great vacation or learning your best friend is moving to California. Instead, it feels more like watching a firework rocket into the sky, explode and then realizing that it is merely good but not great. Okay lah, as we Hong Kongers would say.

Now that the soccer circus has left town and the blare of the vuvuzela is no longer ringing in our ears, we can’t help but feel a little lost. I am not talking about that sense of emptiness we get when something spectacular has finally come to an end, like finishing a great vacation or learning your best friend is moving to California. Instead, it feels more like watching a firework rocket into the sky, explode and then realizing that it is merely good but not great. Okay lah, as we Hong Kongers would say.

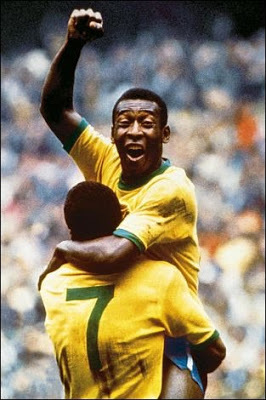

Calling this World Cup a bore or a disappointment would have been too harsh. To be fair, there was no shortage of twists and turns, surprising upsets and reversals of fortune. Who could have predicted that past champions France and Italy would crash out after the second round in such public disgrace? Even the once invincible Brazilians became suddenly beatable, losing 1-2 to The Netherlands in the quarter-finals. But as much as the suspension of disbelief kept our adrenaline rush going, this World Cup has left many a soccer fan unsatisfied, especially those who have been around long enough to remember what it was like to watch the spectacle in the 70s and 80s, with moments so beautiful that they alternately hushed the audience and roused it to a frenzy. As if to prove that none of the star players nowadays is deserving of his celebrity status, Paul the Psychic Octopus, trapped in an aquarium thousands of miles away, stole the show without so much as a kick or a header.

So what’s changed? The world today is a very different place than it was three, four decades ago. During the Cold War era, the notion of friends and foes, us versus them was much more clear cut. Back then international sporting events like the World Cup were as much emotionally charged as they were symbolically significant. But much of that last century romance disappeared when the Eastern Bloc fell, and the world slowly realigned itself into an ever-shifting balance of power among the United States, Europe and China. Perhaps the World Cup would have been more exhilarating if other “Axis of Evil” regimes were to join North Korea in the tournament against the terrorist-fighting West. A playoff between Iran’s Jihadists and America’s Freedom Fighters would have been an epic battle between good and evil worthy of a Shakespearean tragedy.

Technological advancement and mobility of players – spurred by intense inter-league trading – have also changed the game of soccer by leveling the playing field across the globe. Countries can now study each other, learn from each other and, much to soccer fans’ dismay, play like each other. The painfully robotic Germans, for instance, are now able to work the field as gracefully as the Argentineans, whereas the South Koreans these days often display traces of samba football once found only in sweltering Brazil. As styles merge and nationalities blur, the signature moves and quirky antics that make a team instantly recognizable are slowly becoming a thing of the past. And the World Cup that used to draw us in and blow us away has given way to a series of safe and predictable plays, stuff that belongs to the “okay lah” category alongside the Olympics and the Oscars.

But don’t tell that to the Spaniards or the South Africans. First-time champion Spain has obvious reasons to celebrate and for a few days citizens could legitimately take their minds off unemployment and national debt. Just as excited, South Africans patted themselves on the back for throwing a coming-out party without a hitch, making skeptics who warned of violent crime and other calamities look like a bunch of party poopers. While commentators continue to debate how much of the World Cup money will trickle down to the 50% of the South African population living below the poverty line, World Cup 2010 has already paid off by lifting the spirit of a nation still trotting down the arduous road to reconciliation after a half-century of apartheid. Nothing captures Nelson Mandela’s call to “forget and forgive” better than pictures of black South Africans waving the Dutch flags during the final match in support of their former white oppressors. That must be what they mean by the “healing power of sports.”

I have never been a big fan of any spectator sports. Still it wasn’t difficult for me to get into the World Cup spirit in Hong Kong. Here, the quadrennial event is much more than a soccer tournament; it is a high-stake enterprise. The Hong Kong Jockey Club, the dubiously “non-profit” organization that enjoys a legal monopoly over soccer betting, raked in a multi-billion dollar windfall from the 52-game tournament, especially given the large number of surprising results in this World Cup. And in the zero-sum game of soccer gambling, the Jockey Club made its fortune on the backs of grassroots citizens lured by the prospects of winning millions simply by picking the color of the team uniform. And that’s not even counting illegal gambling, a bourgeoning social problem in Hong Kong that spikes with every major soccer tournament broadcast in the city. In the weeks and months ahead, news stories of cash-strapped citizens driven to self-destruction by bookies and loan sharks will begin to surface. Just a few days ago, I read an article in a local newspapers about a problem gambler who lost $100,000, many times his monthly salary, in a single World Cup quarter-final match. It was then I realized that no matter how dull and unexciting the World Cup becomes, we can always count on the addictive power of gambling to bring us back to that SoHo sports bar in the dead of night every four years.

Now that the soccer circus has left town and the blare of the vuvuzela is no longer ringing in our ears, we can’t help but feel a little lost. I am not talking about that sense of emptiness we get when something spectacular has finally come to an end, like finishing a great vacation or learning your best friend is moving to California. Instead, it feels more like watching a firework rocket into the sky, explode and then realizing that it is merely good but not great. Okay lah, as we Hong Kongers would say.

Now that the soccer circus has left town and the blare of the vuvuzela is no longer ringing in our ears, we can’t help but feel a little lost. I am not talking about that sense of emptiness we get when something spectacular has finally come to an end, like finishing a great vacation or learning your best friend is moving to California. Instead, it feels more like watching a firework rocket into the sky, explode and then realizing that it is merely good but not great. Okay lah, as we Hong Kongers would say.

Calling this World Cup a bore or a disappointment would have been too harsh. To be fair, there was no shortage of twists and turns, surprising upsets and reversals of fortune. Who could have predicted that past champions France and Italy would crash out after the second round in such public disgrace? Even the once invincible Brazilians became suddenly beatable, losing 1-2 to The Netherlands in the quarter-finals. But as much as the suspension of disbelief kept our adrenaline rush going, this World Cup has left many a soccer fan unsatisfied, especially those who have been around long enough to remember what it was like to watch the spectacle in the 70s and 80s, with moments so beautiful that they alternately hushed the audience and roused it to a frenzy. As if to prove that none of the star players nowadays is deserving of his celebrity status, Paul the Psychic Octopus, trapped in an aquarium thousands of miles away, stole the show without so much as a kick or a header.

So what’s changed? The world today is a very different place than it was three, four decades ago. During the Cold War era, the notion of friends and foes, us versus them was much more clear cut. Back then international sporting events like the World Cup were as much emotionally charged as they were symbolically significant. But much of that last century romance disappeared when the Eastern Bloc fell, and the world slowly realigned itself into an ever-shifting balance of power among the United States, Europe and China. Perhaps the World Cup would have been more exhilarating if other “Axis of Evil” regimes were to join North Korea in the tournament against the terrorist-fighting West. A playoff between Iran’s Jihadists and America’s Freedom Fighters would have been an epic battle between good and evil worthy of a Shakespearean tragedy.

Technological advancement and mobility of players – spurred by intense inter-league trading – have also changed the game of soccer by leveling the playing field across the globe. Countries can now study each other, learn from each other and, much to soccer fans’ dismay, play like each other. The painfully robotic Germans, for instance, are now able to work the field as gracefully as the Argentineans, whereas the South Koreans these days often display traces of samba football once found only in sweltering Brazil. As styles merge and nationalities blur, the signature moves and quirky antics that make a team instantly recognizable are slowly becoming a thing of the past. And the World Cup that used to draw us in and blow us away has given way to a series of safe and predictable plays, stuff that belongs to the “okay lah” category alongside the Olympics and the Oscars.

But don’t tell that to the Spaniards or the South Africans. First-time champion Spain has obvious reasons to celebrate and for a few days citizens could legitimately take their minds off unemployment and national debt. Just as excited, South Africans patted themselves on the back for throwing a coming-out party without a hitch, making skeptics who warned of violent crime and other calamities look like a bunch of party poopers. While commentators continue to debate how much of the World Cup money will trickle down to the 50% of the South African population living below the poverty line, World Cup 2010 has already paid off by lifting the spirit of a nation still trotting down the arduous road to reconciliation after a half-century of apartheid. Nothing captures Nelson Mandela’s call to “forget and forgive” better than pictures of black South Africans waving the Dutch flags during the final match in support of their former white oppressors. That must be what they mean by the “healing power of sports.”

I have never been a big fan of any spectator sports. Still it wasn’t difficult for me to get into the World Cup spirit in Hong Kong. Here, the quadrennial event is much more than a soccer tournament; it is a high-stake enterprise. The Hong Kong Jockey Club, the dubiously “non-profit” organization that enjoys a legal monopoly over soccer betting, raked in a multi-billion dollar windfall from the 52-game tournament, especially given the large number of surprising results in this World Cup. And in the zero-sum game of soccer gambling, the Jockey Club made its fortune on the backs of grassroots citizens lured by the prospects of winning millions simply by picking the color of the team uniform. And that’s not even counting illegal gambling, a bourgeoning social problem in Hong Kong that spikes with every major soccer tournament broadcast in the city. In the weeks and months ahead, news stories of cash-strapped citizens driven to self-destruction by bookies and loan sharks will begin to surface. Just a few days ago, I read an article in a local newspapers about a problem gambler who lost $100,000, many times his monthly salary, in a single World Cup quarter-final match. It was then I realized that no matter how dull and unexciting the World Cup becomes, we can always count on the addictive power of gambling to bring us back to that SoHo sports bar in the dead of night every four years.

Published on July 15, 2014 05:00

July 1, 2014

We Have Spoken 我們發聲了

I have taken part in every July 1 march since I moved back to Hong Kong in 2005. That makes yesterday’s march my ninth. I have the routine down pat: I will put on a black T-shirt, eat a hearty lunch and agree on a time to meet my friends in Causeway Bay. I will bring both sunscreen and a small umbrella because the Hong Kong summer, like its politics, is never predictable. Take this year for instance. Who would have thought that Beijing would release the bluntly-worded White Paper – an assertion of total control over the city and a bonanza for protest organizers – less than a month before the most politically sensitive day on our calendar?

A crowd like no other

A crowd like no otherAt the Central MTR station, I was about the only man in black. I must have missed the call on social media to wear white to mock the White Paper. But it didn’t matter, because our minds were somewhere else when the train reached Causeway Bay. We were awed by the sheer number of people inching away from the platform. It was like a Chinese New Year flower market except this crowd was bigger and more orderly. There is a lot on our minds these days and we wanted to say it with our feet. And the people have spoken.

I met up with a friend in front of Sogo. Matthew, a Shanghai native, is a law professor at Hong Kong University. This is his fifth year in the city but his first time joining a march. I told Matt that people came out not only because of the White Paper but also to vent our anger over a laundry list of issues: the northeastern NT redevelopment bill, Beijing’s stance on the 2017 chief executive election and its outright dismissal of the unofficial referendum on election methods in which nearly 800,000 Hong Kongers had participated. I also told Matt that we must enter Victoria Park to be counted by the police, and that authorities routinely under-report the headcount to downplay the level of public frustration. But it didn’t matter, because I was there and I saw it with my own eyes. The size of the crowd this year was not like anything I had seen the other eight times. I knew the people have spoken.

Causeway MTR station

Causeway MTR stationOver the course of the march, I took pains to visit as many as sidewalk booths as I could. I waved at Lee Cheuk Yan (李卓人), union leader and chairman of the Democratic Alliance. I shook the hands of all three Occupy Central organizers – Benny Tai (戴耀廷), Chu Yiu-ming (朱耀明) and Chan Kin-man (陳健民) – and told them how thankful I was for all that they have done and still to do. I also chatted with Erica Yuen (袁彌明), chairlady of People Power. She offered to meet me at her party booth near Wanchai’s Southorn Playground if I wanted to talk more and ask her a few questions. I said “sure,” although I knew I probably wouldn’t see her again for the rest of the day. I had to move with the crowds and stay with my friend. But it didn’t matter, because I had no questions and she need not give me any answers. The turnout yesterday was more powerful than any statement a politician could make. For the people have spoken.

People Power's Erica Yuen

People Power's Erica YuenBy the time we reached Admiralty and the office towers in Central came into view, the sun had begun to set. The sky suddenly dimmed and the rain started to come down in sheets. Colorful umbrellas pop-opened like daisies. I couldn’t tell whether the untimely downpour was angel tears or a divine intervention to disperse the crowds. But it didn’t matter, because someone somewhere started playing “Under a Vast Sky” (《海闊天空》) through a megaphone. The song, written by a beloved 80s Cantopop band, speaks of ideals and defiance and is the closest thing to a national anthem we have. The marchers instantly broke into song, and the words sent goose bumps all over my soaked body. Rain? What rain? The people have spoken!

Rain? What rain?

Rain? What rain?We left the rally near Pedder Street. At a café, I went through the photos on my phone and posted some of them on Facebook and Instagram. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then these images would amount to a history book. The pictures of citizens streaming down Hennessy Road, of old people and young people and people in wheelchairs, didn’t just record history, they reclaimed it. After I said goodbye to Matthew, I bowed my head and said a prayer for the students who would remain on Chater Road for an overnight sit-in and who would almost certainly be removed by riot police. I also prayed for the upcoming Occupy Central showdown, a battle that we can’t win but still must fight. Perhaps that, too, doesn’t matter, because the people have already spoken.

They need all the support they can get

They need all the support they can get

Published on July 01, 2014 10:06

June 11, 2014

Why We Should All Thank Long Hair 多謝長毛

Following the Legco election in 2004, The Economist, in an article titled “Suffrage on Sufferance,” had this to say about one of our lawmaker-elects:

“The unexpected election of Leung Kwok-hung, better known as ‘Long Hair’ – whose other main claims to fame are his Che Guevara T-shirts and rants against the chief executive... – suggests that many voters treated both the election and the toothless Legco as a joke.”

The British newspaper opined that Mr. Leung, with his fiery rhetoric and raggedy hairdo, is nothing more than an attention-grabbing troublemaker, and that by voting a clown into the Legco Hong Kong citizens must not have taken the election seriously.

Rebel with a cause

Rebel with a causeThe article led me to two thoughts.

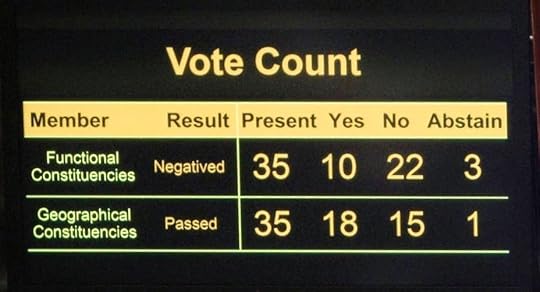

First, whoever wrote it didn’t have a very good grasp of our political reality. Hong Kong has one of the most undemocratic legislative systems in the civilized world. Among the many anomalies, there is a political invention called the “functional constituencies” (功能議席) who take up half of the Legco’s 70 seats. Under the current rules, any government-proposed bill requires a simple majority from the 70 seats voting together. Bills introduced by individual lawmakers, on the other hand, are subject to the logic-defying “separate vote count” (分組點票) procedure and must secure a majority of votes from both the functional seats and the non-functional seats voting separately. Since none of the functional constituencies is democratically elected (they are picked by a small circle of voters within a trade or interest group) and nearly all of them are pro-establishment businessmen, you can see how the rules are custom-made to block any proposal made by the opposition, such as a motion to investigate C.Y. Leung’s corruption allegations.

What does this have to do with Long Hair? Pretty much everything. Our dysfunctional political system means that being a “moderate” Pan-democrat such as a member of the Civic Party (公民黨) or the Democrats (民主黨) is about as useful as a knife without a blade. Wagging their fingers at the government on the Legco floor may make these goody-two-shoes politicians look like people’s heroes on the evening news, but it does nothing to change the status quo. In other words, if the poker game is rigged, the player will only keep losing if he continues to play by the rules, no matter how hard he racks his brain.

Functional constituencies at work:

Functional constituencies at work: another opposition-proposed bill vetoed

That’s exactly what Long Hair and his so-called “radical” friends like Raymond Wong (黃毓民) and the folks from People Power (人民力量) refuse to do: play by the rules and lose game after game. They understand that as long as the playing field remains lopsided, they need to think and play outside the box. And so these rebel fighters organize mass protests, stage days-long filibusters and come up with innovative campaigns like the de facto referendum. Their efforts have yielded real results, often by raising enough stink to tip the balance of public opinion and forcing the government to back down from a bad bill. What's more, their shenanigans highlight the unfairness of our twisted political system and, in the process, inspire citizens to be interested and get involved. In their relatively young political careers, Long Hair and his comrades have managed to accomplish more than the rest of the Pan-democrats have done in the 17 years since the Handover.

Long Hair during a filibuster

Long Hair during a filibusterMy second thought after reading The Economist article is more depressing: if a world-class newspaper doesn’t get our system, what chance does an average tabloid-reading, soap-opera-watching, politics-averse Hong Konger have? Indeed, ask anyone on the street and he will likely describe Long Hair and his likes as extreme, belligerent and irrational. Their good work is written off as destructive and counter-productive. After all, images of these firebrand lawmakers throwing bananas at the chief executive or shoving paper coffins into the faces of cabinet members make a far deeper impression than what they try to achieve and why they have to do it in the first place.

Whenever the dinner conversation turns political, I find myself defending Long Hair and his allies. In a city where Confucian ethics still inform our value judgment, social propriety is placed above all other priorities. We tend to reward the well-mannered villains and penalize the unruly heroes. That means no matter how hard Long Hair fights for his good causes, from a universal retirement scheme to universal suffrage in 2017, and no matter how much he is holding C.Y. Leung to task and keeping him and his minions on their toes, he will only be remembered for his untoward antics.

If he wears a suit and speaks gently, he must be trustworthy

If he wears a suit and speaks gently, he must be trustworthyApropos, this past Monday an appellant court upheld Long Hair’s conviction for “behaving in a disorderly manner” during a public debate in 2011. He was immediately taken to his prison cell to serve a four-week sentence. A day later, his trademark locks were cut, rendering the recognizable lawmaker unrecognizable. Many people I know applauded the turn of events as a wayward politician's just desert for being a nuisance to society and setting a bad example for our children.

So I once again found myself defending Long Hair, except this time I was able to point to an altogether different reason why we should be grateful for having him around: Long Hair goes to prison so we don’t have to. Whereas most moderate Pan-democrats treat their political careers like, well, a career and squirm at the first sign of personal ruin, Long Hair treats it as a religious duty and is prepared to go all out and lose it all. As the city’s political future comes to a critical juncture – just two days ago, Beijing released a surprisingly blunt white paper asserting its total control over Hong Kong to intimidate the Occupy Central movement – we need people like Long Hair more than ever.

Long hair no more

Long hair no more

Published on June 11, 2014 19:24

June 3, 2014

The Butcher’s Atonement 屠夫的救贖

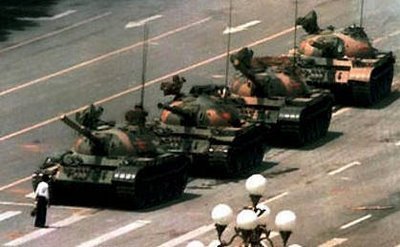

The other night my niece asked me to tell her the story of Tiananmen Square. My avuncular instincts kicked into high gear and I made up a story more suited for juvenile consumption.

The butcher butchers, and the butcher denies

The butcher butchers, and the butcher denies

* * *

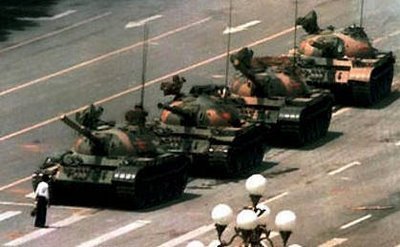

The Tiananmen Square Massacre, or more delicately referred to in this part of the world as the “June 4 Incident,” was the most senseless chapter in Chinese history since the Cultural Revolution. On June 3, 1989, if Beijing citizens had to make a list of things they thought would never happen, their government using the bluntest arrows in their authoritarian quiver, by sending in the tanks in the dead of night and opening fire on unarmed demonstrators still asleep in their tents, would have been right at the top of their list.

The chain of events that led up to the bloody crackdown was more surreal than a Dali painting. Not two months before June 4, exuberant students camped out in the heart of the capital city, shouting rousing slogans one moment and singing the Internationale the next. Two weeks before June 4, student leaders wearing headbands and pajamas sat side-by-side with party chiefs in the Great Hall of the People exchanging ideas on political reform. Such fatal naiveté! How could anyone place even an ounce of trust in a regime utterly incapable of negotiation or compromise, or ever believe that lofty ideals would somehow move party seniors who took the slightest criticism as a personal affront? In the end, the student demonstrators got a lesson no textbook could teach them. And hundreds became part of a story they would never live to tell.

Secretary Zhao Ziyang would pay a high price for speaking to the students

Secretary Zhao Ziyang would pay a high price for speaking to the students

Twenty years later, Tiananmen Square was once again in a complete lock-down. Security had been heightened and armed police were everywhere. Determined to make the anniversary a national non-event, authorities summarily removed dissidents from the capital city and kept the less vocal ones under temporary house arrest. Twitter, Hotmail and Flickr had been blocked for a “national Internet service maintenance day.” But Beijing has little to worry about. June 4 is nothing but a historical blip for most Mainland Chinese. Young people born after the incident haven’t even a chance to learn or hear anything about it, at least not through public discussions or school books. And in a country that boasts the fastest growing population of millionaires in the world, money speaks louder than ideology. Lured by the promise of a comfortable middle-class life, many opt for a foreign car and a big apartment over political reform that may or may not benefit them within their lifetime. These days, university students are busy applying to graduate schools in America and interviewing with multinational companies, in what many believe to be a modern reenactment of Goethe’s tragic play Faust. From fearless idealists to unabashed pragmatists, the pendulum has swung to the other extreme in a single generation.

Sorry, the square is closed for maintenance

Sorry, the square is closed for maintenance

In Hong Kong, the only place on Chinese soil where free discussions of the massacre are possible, a couple of interesting preludes set the stage for the 20th anniversary. In April, Ayo Chan (陳一諤), the dorky know-nothing student president at the University of Hong Kong, outraged his colleagues at a campus forum when he suggested that the entire tragedy could have been avoided if the demonstrators had not behaved irrationally and provoked the Communist Party. Thankfully, fellow students acted swiftly to impeach the loose-tongued freshman before he moved on to the subject of the Holocaust and accused the Jews of taunting the Nazis.

Just two weeks ago, Chief Executive Donald Tsang told legislators that whatever happened in Beijing that day “happened a long time ago” and that the incident was better forgotten given all the prosperity China has brought us. And as if things weren’t bad enough, the bow-tied bureaucrat kept on stressing that his view represented the opinion of every Hong Kong citizen. Politicians are well advised to speak cautiously, and if that’s too hard to do, speak only for themselves. From university leader to government head, those who lack the maturity or conscience to separate facts from lies in the grown-up world should join my niece in learning the story of the old butcher. Learn it and remember it.

All that sucking up to Beijing has gotten him nowhere

All that sucking up to Beijing has gotten him nowhere

Earlier tonight I attended the candlelight vigil at Victoria Park. With teary eyes and a heavy heart, I put on a black-and-white outfit as if I were going to a dear friend’s funeral. At the park, somber citizens occupied every occupiable space as far as the eye could see. To my left, a young couple held on to their infant fast asleep in the summer’s heat. To my right, a sweaty teenager led two blind men negotiating the crowds with their walking sticks. Every one of us chanted pro-democracy slogans and strained to hear impassioned speeches drowned out by the chorus of cicadas singing loudly in the trees. Twenty years ago, demonstrators besieged Tiananmen Square to demand the vindication of ousted party chief Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦). Twenty years later, I found myself among 150,000 sitting in a peaceful protest demanding the vindication of those very demonstrators. Despite Hong Kong’s many foibles and political anomalies, tonight our city was the collective conscience of the 1.3 billion Chinese people around the globe and a beacon of hope for a better China. I had never been more proud of being a part of this city.

The annual vigil at Victoria Park

The annual vigil at Victoria Park

* * *

If this were a fairy tale, my niece would thank me for the lovely bed-time story and fall sound asleep under her quilt embroidered with giraffes and zebras. But we don’t live in a fairy tale. In reality, my nieces and nephews never asked me about Tiananmen Square and I never told them the story of the old butcher and his slaughtered children. Our next generation is either too young to be interested in politics or too busy with homework and exams. But how I want them to ask me what this anniversary really means! I want my next generation to know their country and its history, for how we remember our past defines who we are and how we live our future. Throughout the night, Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem Recessional kept playing in my head. And on this 20th anniversary of one of the defining moments of my childhood, I dedicate these lines to my next generation:

The tumult and the shouting dies, The captains and the kings depart. Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice, An humble and a contrite heart. Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget - lest we forget!

Lest we forget!

Lest we forget!

_______________________

Once upon a time in a land far far away, an old butcher ran a humble meat shop. One hot summer’s night, he got into a heated argument with his sons over the way he managed his struggling business. In a fit of rage, the impetuous father reached for his cleaver and went on a bloody rampage. Shocked by his own monstrosity, the man frantically buried the bodies and vowed to be a better father to his remaining children. As the years passed, the butcher shop prospered and the family grew. Still, any discussion of that fateful summer’s night remained taboo. Convinced that he would never be forgiven, the old man resigned himself to waiting out the generation who witnessed his murderous acts. With each passing day, as memories thinned and denial thickened, the old butcher’s chance of atonement ebbed away like a receding tide.

The butcher butchers, and the butcher denies

The butcher butchers, and the butcher denies* * *

The Tiananmen Square Massacre, or more delicately referred to in this part of the world as the “June 4 Incident,” was the most senseless chapter in Chinese history since the Cultural Revolution. On June 3, 1989, if Beijing citizens had to make a list of things they thought would never happen, their government using the bluntest arrows in their authoritarian quiver, by sending in the tanks in the dead of night and opening fire on unarmed demonstrators still asleep in their tents, would have been right at the top of their list.

The chain of events that led up to the bloody crackdown was more surreal than a Dali painting. Not two months before June 4, exuberant students camped out in the heart of the capital city, shouting rousing slogans one moment and singing the Internationale the next. Two weeks before June 4, student leaders wearing headbands and pajamas sat side-by-side with party chiefs in the Great Hall of the People exchanging ideas on political reform. Such fatal naiveté! How could anyone place even an ounce of trust in a regime utterly incapable of negotiation or compromise, or ever believe that lofty ideals would somehow move party seniors who took the slightest criticism as a personal affront? In the end, the student demonstrators got a lesson no textbook could teach them. And hundreds became part of a story they would never live to tell.

Secretary Zhao Ziyang would pay a high price for speaking to the students

Secretary Zhao Ziyang would pay a high price for speaking to the students Twenty years later, Tiananmen Square was once again in a complete lock-down. Security had been heightened and armed police were everywhere. Determined to make the anniversary a national non-event, authorities summarily removed dissidents from the capital city and kept the less vocal ones under temporary house arrest. Twitter, Hotmail and Flickr had been blocked for a “national Internet service maintenance day.” But Beijing has little to worry about. June 4 is nothing but a historical blip for most Mainland Chinese. Young people born after the incident haven’t even a chance to learn or hear anything about it, at least not through public discussions or school books. And in a country that boasts the fastest growing population of millionaires in the world, money speaks louder than ideology. Lured by the promise of a comfortable middle-class life, many opt for a foreign car and a big apartment over political reform that may or may not benefit them within their lifetime. These days, university students are busy applying to graduate schools in America and interviewing with multinational companies, in what many believe to be a modern reenactment of Goethe’s tragic play Faust. From fearless idealists to unabashed pragmatists, the pendulum has swung to the other extreme in a single generation.

Sorry, the square is closed for maintenance

Sorry, the square is closed for maintenanceIn Hong Kong, the only place on Chinese soil where free discussions of the massacre are possible, a couple of interesting preludes set the stage for the 20th anniversary. In April, Ayo Chan (陳一諤), the dorky know-nothing student president at the University of Hong Kong, outraged his colleagues at a campus forum when he suggested that the entire tragedy could have been avoided if the demonstrators had not behaved irrationally and provoked the Communist Party. Thankfully, fellow students acted swiftly to impeach the loose-tongued freshman before he moved on to the subject of the Holocaust and accused the Jews of taunting the Nazis.

Just two weeks ago, Chief Executive Donald Tsang told legislators that whatever happened in Beijing that day “happened a long time ago” and that the incident was better forgotten given all the prosperity China has brought us. And as if things weren’t bad enough, the bow-tied bureaucrat kept on stressing that his view represented the opinion of every Hong Kong citizen. Politicians are well advised to speak cautiously, and if that’s too hard to do, speak only for themselves. From university leader to government head, those who lack the maturity or conscience to separate facts from lies in the grown-up world should join my niece in learning the story of the old butcher. Learn it and remember it.

All that sucking up to Beijing has gotten him nowhere

All that sucking up to Beijing has gotten him nowhereEarlier tonight I attended the candlelight vigil at Victoria Park. With teary eyes and a heavy heart, I put on a black-and-white outfit as if I were going to a dear friend’s funeral. At the park, somber citizens occupied every occupiable space as far as the eye could see. To my left, a young couple held on to their infant fast asleep in the summer’s heat. To my right, a sweaty teenager led two blind men negotiating the crowds with their walking sticks. Every one of us chanted pro-democracy slogans and strained to hear impassioned speeches drowned out by the chorus of cicadas singing loudly in the trees. Twenty years ago, demonstrators besieged Tiananmen Square to demand the vindication of ousted party chief Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦). Twenty years later, I found myself among 150,000 sitting in a peaceful protest demanding the vindication of those very demonstrators. Despite Hong Kong’s many foibles and political anomalies, tonight our city was the collective conscience of the 1.3 billion Chinese people around the globe and a beacon of hope for a better China. I had never been more proud of being a part of this city.

The annual vigil at Victoria Park

The annual vigil at Victoria Park* * *

If this were a fairy tale, my niece would thank me for the lovely bed-time story and fall sound asleep under her quilt embroidered with giraffes and zebras. But we don’t live in a fairy tale. In reality, my nieces and nephews never asked me about Tiananmen Square and I never told them the story of the old butcher and his slaughtered children. Our next generation is either too young to be interested in politics or too busy with homework and exams. But how I want them to ask me what this anniversary really means! I want my next generation to know their country and its history, for how we remember our past defines who we are and how we live our future. Throughout the night, Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem Recessional kept playing in my head. And on this 20th anniversary of one of the defining moments of my childhood, I dedicate these lines to my next generation:

The tumult and the shouting dies, The captains and the kings depart. Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice, An humble and a contrite heart. Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget - lest we forget!

Lest we forget!

Lest we forget!_______________________

If you like this article, read 36 others like it in HONG KONG State of Mind, now available at major bookstores in Hong Kong, on Amazon and at Blacksmith Books.

Published on June 03, 2014 09:01

May 14, 2014

It’s Complicated 化繁為簡

I grew up in a small flat in Hong Kong. To keep our shoebox of a place organized, my parents gave each of the five children a drawer to store their earthly possessions. Everything I owned growing up – coloring pencils, comic books, a secret stash of Haribo extra-sour cola bottles – had to fit inside a space roughly the size of a briefcase. And everything did. Throughout my childhood, that drawer was my whole life and my whole life was that drawer. When I left for boarding school in my teens, I emptied my belongings into a bag, packed a few pieces of clothing and went on my freewheeling way.

My childhood in a drawer

My childhood in a drawerTwenty some years later, things cannot have been more different. The age of owning just one – one backpack, one pair of jeans, one Casio digital watch – is long gone. My current flat, though bigger than the one I grew up in, is bursting at the seams with stuff. Just stuff. I have two iPads, three wine buckets and six area rugs. My kitchen is a Noah’s Ark filled with gadgets I use once or twice a year. Whatever the difference is between a blender, a juicer and a food processor, I have at least one of each. Over the years, I have managed to amass nearly a dozen miniature Eiffel Towers – in the form of key chains, fridge magnets and snow globes – which I had inadvertently purchased myself or reluctantly received from friends.

Then there is my closet, that Ninth Circle of Inferno. Twice a year, I change out my wardrobe, putting away off-season clothes and swapping in things to wear for the coming months. I went through the Great Migration just last week. By a quick count, I own nine pairs of jeans, 16 polo shirts and 26 pairs of shorts. 26 pairs of near identical shorts! Yet, like most people, I only put on the same couple of favorites and complain I don’t have anything to wear. And so I keep on buying more. To make room for the new, I give away anything I haven’t worn in a year. That makes my brother Kelvin, who wears the same size as me, the primary beneficiary of my shopaholism.

Does your closet look like this too?

Does your closet look like this too?I have to wonder: how did I go from the wise kid who lived by Mies van der Rohe’s motto “less is more” to this out-of-control packrat who hoards like Scrat in the Ice Age films?

A big part of it is basic supply and demand. In the two and half decades since the halcyon days of my youth, consumer goods have become much more affordable. Cheap labor and economies of scale in China – the World’s Factory that manufactures 90% of the planet’s personal computers and 60% of its shoes – have driven down production costs and pumped up our purchasing power. Whereas worker bees a generation ago would think twice before investing in a winter coat, impulse buyers these days grab one in every color without batting an eyelid. When a polo shirt costs less than a beer, shoppers can binge at H&M or Uniqlo like it is an all-you-can-eat buffet.

What’s more, globalization and social media have enabled new product rollouts to reach every corner of the world with the click of a mouse, instantly turning our wants into needs and needs into needless clutter. What was once fashionable can become hopelessly uncool in a matter of months (try using an iPhone 4 at a party). And things that didn’t even exist a few years ago suddenly become must-haves we can’t live without (count the number of noise-cancelling earphones on any given flight). All those old phones, old cameras and old laptops, each with an unwieldy charger, get dumped into a box labelled “too expensive to toss, too embarrassing to use.”

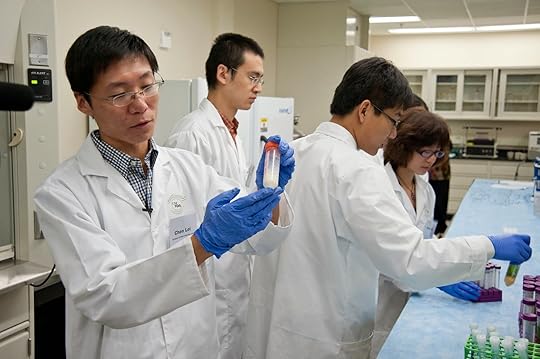

Their low wages make us feel wealthier

Their low wages make us feel wealthierOn a deeper psychological level, being surrounded by things, especially nice things, gives us a sense of security and self-validation. Rolexes and Birkins are as much a reward for our hard work as they are wearable milestones that mark our progress in life. Furthermore, we buy in order to fulfil an emotional need. One of the reasons I dropped a silly sum of money on hiking gear – headlamps, titanium walking sticks and a trekking watch with a built-in barometer and altimeter – is to compensate for not getting out enough. The less we do, the more we must own.

What we own can end up owning us, warns Tyler Durden, underground boxer and anti-materialist in the movie Fight Club. I don’t need to be a soap salesman to know the truth in that. With my flat filled to the brim with clutter, I had to rent a 50-square-foot locker in a remote storage facility to house my junk. That means month after month, good money is thrown after bad simply to keep things out of sight and out of mind. As a watch collector, I dutifully polish and hand-wind my timepieces every week. A spate of burglaries in my building last winter gave me a panic attack and prompted me to purchase a safe to keep my collection out of harm’s way. Then there is the wine vault to store my prized Bordeaux and a dry cabinet to house a full suite of camera lenses. Little by little, I become a glorified security guard watching over possessions I never thought I needed and sometimes forget I have. I can only imagine what an indentured servant one must feel to own a 60-foot yacht or a 15-room estate, no matter what bragging rights they promise.

Rolex-mania in Hong Kong

Rolex-mania in Hong KongThe 21st Century epiphany that we can live more by owning less has spawned a minimalist movement in the developed world. In the United States, marketing director-turned-life coach Dave Bruno started a “The notion that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication has its appeal. Downshifting is both financially smart and emotionally liberating. It cuts down unnecessary expenses and frees our minds from mundane thoughts. But does it really? Critics of Bruno’s challenge are quick to point out that living with less can be expensive and stressful. To maintain a minimalist existence, we may end up spending more, for instance, to replace useful things we have chivalrously thrown out. We rack our brain trying to decide whether to use our precious quota on a coffee machine or a toilet brush. The 100 Thing Challenge, it seems, has simply replaced one existential obsession with another.

Bruno's book is now a national bestseller

Bruno's book is now a national bestsellerIn the end, we cannot achieve happiness by owning either too much or too little. True luxury, after all, is about not having to think about these questions in the first place. There is nothing wrong with being materially comfortable, as long as we are cognizant of what earthly things can and cannot do. Life gets more complicated with each generation and that’s the way it will always be. I can never go back to living out of a drawer – nor do I want to.

Still, I concede there is something to be said about decluttering and reducing waste. I have devised a simple trick: I will take pictures of my bloated closet and storeroom and look at them each time I take something to the cash register. The stress of not knowing where to put my new purchase will quell my urge to buy. The money I save will then go toward an early retirement fund. It is a win-win proposition that doesn’t require hawking heirlooms or recycling dirty underwear.

Lots to learn from the Japanese

Lots to learn from the Japanese* * *

This article previously appeared in the May/June 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column "The Urban Confessional."

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

Published on May 14, 2014 09:58

April 14, 2014

The Dating Game 過期照食

I have a perverse household routine. Every few months, I’ll go through my kitchen cabinet looking for expired food. Canned tuna, tea bags and rice – items for which I’d paid good money – will all go into the trash. Once I’m done with that, I’ll move on to the refrigerator to weed out the proverbial bad apples: a half-dozen eggs, a bottle of chili sauce that I used once or twice, a wedge of cheese still in its original sealed wrap. The purge is indiscriminate and my guilt palpable. I’ll start talking to the garbage can: “Sorry,” “forgive me,” “I’m a terrible person”. But there’s nothing I can do: I’m just doing what the white labels say.

What does that mean?

What does that mean?I know I’m not alone. Each day we toss out perfectly good food that is past its prime, all because of that tiny, hard-to-read six-digit death sentence called the expiration date. But expiration dates are a modern mystery. For starters, the wording is confusing and inconsistent – no one knows whether “sell by,” “use by” and “best before” all mean the same thing. How much flexibility there is with the dates often plunge us into the metaphysical: Does the milk know to spoil at the stroke of midnight? Will time dilate if I move the chicken to the freezer? How can unopened wine go bad when it’s supposed to get better with age? We don’t know and we don’t want to take our chances. When in doubt, we toss it out.

According to the United Nations, over a billion tonnes of food is lost or wasted worldwide every year. In America, as much as 40% of all the food produced – worth US$165 billion annually – ends up in the landfill. A recent Harvard University study finds that a major driver of food waste is expiration date confusion. Over 90% of Americans prematurely throw away edible food because they misinterpret food dates. One in five consumers mistakes the date of manufacture (which is used by factories for record purposes) or the “sell by” date (which is used by retailers for inventory control) for the expiration date. The main culprit is the lack of government oversight. With the exception of baby formula, date labels a

Food waste is a global epidemic

Food waste is a global epidemicFolks in Asia don’t fare much better either. In Hong Kong, for instance, the city produces 8,700 tonnes of solid waste every day, 40% of which is uneaten food. The problem is exacerbated by large supermarket chains that pull items off the shelves days before the sell-by date in the name of consumer protection. Friends of the Earth, a local watchdog, estimates that about a third of what stores throw out – around 30 tonnes daily – is still edible, an amount enough to feed over 48,000 three-member households for a day. Worse, supermarket chains are known to destroy food that is close its expiration by shredding it or soaking it in chlorine to discourage waste-pickers from taking it home. They weren’t joking when they said there is no free lunch in Hong Kong.

To properly understand expiration dates, we have to start from the 1970s when date labelling emerged as part of the consumer rights movement. The dates were introduced by the food industry – and adopted voluntarily by manufacturers – to convey freshness. They indicate the period within which a product is at its peak, when it looks and tastes the best. Just because the food is no longer in its prime, however, doesn’t make it unsafe to eat or even taste bad. In other words, expiration dates are about quality instead of safety or public health. But perhaps because we urbanites are so far removed from food production, we choose to believe otherwise. Little do we know that most food-related illnesses are caused by contamination during production and delivery – by pathogens such as E.Coli and salmonella – instead of the passage of time. It didn’t take long for food manufacturers to notice that confusion and paranoia can be very profitable. Over the years, they began to put an expiration date on every product, even things that last a very long time like vinegar, honey and salt. The logic is simple: the more food we throw away, the more money we spend on replenishing it.

Buy, buy, buy

Buy, buy, buyExactly how food manufacturers come with up these expiration dates is also a point of contention. Consumers assume that a team of experienced scientists in white lab coats is stationed at every factory to perform elaborate tests on food. They can’t be more wrong. According to the Natural Resources Defence Council, 80% of all expiration dates are guesswork. Most small- to medium-sized companies lack the resources to conduct proper studies and they simply pick a conservative date to avoid lawsuits.

As for multinational giants like Kraft and Nestlé, they take food dating more seriously but the devil is in the details. When determining shelf life, they build in a safety cushion by assuming that their products will be handled by the most irresponsible consumer: those who let their milk sit on the kitchen counter for hours or leave their potato chips under direct sunlight. And why not? No one will complain – or even notice – if the expiration date turns out to be too short. That, combined with increased sales from premature disposals, make short-dating a win-win proposition for food companies.

That's what we think

That's what we thinkThat takes me back to my household routine. I have decided to kick my old habit and rely on my own judgment instead of blindly following the white labels. For milk, bread and raw meat, I now add a three-day grace period. Things like potato chips and candy bars get an extra month or two. For more shelf-stable items like canned food and condiments, I simply ignore the expiration dates and revert to the time-honoured smell test. After all, our five senses are our best tools to determine what’s safe to eat. Millennia of evolution have given the human species the instinct to tell good food from bad, the same ability on which our grandparents relied before there were supermarkets. Besides, isn’t that what we do when we buy undated produce from street vendors or at the farmers’ market?

The idea of ignoring expiration dates may be difficult for some to swallow. But one man’s discarded food can be another man’s meal. For the germaphobes among us, they can pack items like expired canned soups and instant noodles neatly in a box and leave it outside their backdoor. Someone – whether it is the garbage collector or an environmentally-conscious neighbour – will pick it up and decide for themselves whether it is good to eat. That’s the same concept as the dozens of so-called “expired supermarkets” in America that sell just-expired food at deeply discounted prices to low income families.

Yet, the best way to play the dating game is by trimming. We can substantially reduce food waste simply by buying less, despite the temptation to shop in bulk to save a few bucks or avoid an extra trip to the supermarket. Doing that will not only reduce carbon emission from waste disposal, but also cut down our grocery bill. Food waste may be a first world problem, but it hardly requires a first world solution.

Win-win for both wallet and planet

Win-win for both wallet and planet* * *

This article previously appeared in the April 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column "The Urban Confessional."

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

Published on April 14, 2014 09:29

March 26, 2014

Occupy Taipei 佔領台北

They call it the Sunflower Revolution. Last Tuesday, scores of university students stormed into the legislature in Taipei and took over the premises. Their grievance? Kuomintang (國民黨), the country’s ruling party, tried to ratify a controversial trade agreement with Mainland China without proper review by lawmakers. A few days later, a smaller group raided the cabinet building but were later removed by riot police. In all, over 10,000 people participated in the largest student-led protest in the country’s 65-year history.

Rebels with a cause

Rebels with a causeThings are relatively tame in the second largest city Kaohsiung. Around 200 people – students, taxi drivers, store owners and office workers – congregated outside Kuomintang’s local office on Jianguo First Road (建國一路). That’s where my brothers and I found ourselves this Sunday. We took pictures with our big cameras and chanted slogans with the crowd. The organizers spotted us and invited their “supporters from Hong Kong” to say a few words on stage. We thanked them for asking but politely declined. We told them our Mandarin isn’t very good. In truth, we didn’t know enough about the trade pact to say anything intelligent.

As it turned out, neither do most people in Taiwan. False rumors about the trade pact abound. The fear that Mainlanders will be allowed to buy their way into Taiwan, for instance, turned out to be misplaced. The agreement does not confer either citizenship or permanent residency. It all goes to show how little public discussion – and proper consultation – there has been over the agreement, which takes us back to what triggered the student protest in the first place: the government’s unilateral move to push through a contentious bill without a line-by-line review.

Me, among the protestors in Kaohsiung

Me, among the protestors in KaohsiungSo what’s this agreement and what’s in it?

Formally known as the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA, 服貿), the pact was signed in Shanghai in June 2013. It is one of two major sequels (the other one being the not-yet-signed “Agreement on Trade in Goods”) to the high-level, largely symbolic Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA, 兩岸經濟協議) inked in 2010. CSSTA is all about opening up the service industry in both countries. It aims at creating cross-strait investment opportunities in dozens of service-related sectors (64 in Taiwan and 80 in China), such as banking, healthcare, tourism, films and telecommunications. Among other things, CSSTA will allow qualified professionals in Mainland China to apply for short-term (three-year) visas to work in Taiwan, and vice versa. Mainland corporations, such as banks and mobile service providers, will be able to set up branches and offices in Taiwan or purchase stakes in Taiwanese companies within the permitted industries, and vice versa.

Overwhelming opposition

Overwhelming oppositionCSSTA is long on commitments but short on details. Exactly how many visas will be issued each year and what level of foreign investment is permitted will be the subject of further negotiations. Implementation is to be monitored and specifics are to be worked out in the years to come. So while CSSTA is a meatier follow-up to ECFA, there is still a way to go before the rubber actually hits the road.

Neither the lack of understanding nor the lack of details about the trade pact, however, has stopped people from condemning it. It is so for two reasons. First, the public is offended by not so much what is inthe agreement as the way their government has tried to pull a fast one on them. President Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) attempt to slip the bill under the radar screen is just another confirmation that he is more concerned about salvaging his tattered legacy than looking out for his country. CSSTA was intended to be the stone that kills two political birds: on the one hand, it is a step closer to the economic integration that the China-friendly Ma has been engineering. On the other hand, it is a badly needed jolt to the languishing economy for which he is blamed. But everything has now backfired. The Sunflower Revolution has not only turned back the clock on cross-strait relations, but also taken a further toll on Ma’s dwindling popularity. His approval rating has been hovering at a pitiful 9%, the lowest among leaders in the developed world.

He makes Nixon look popular

He makes Nixon look popularThe second reason has to do with the natural suspicion of a unification-obsessed China. Many Taiwanese view ECFA and CSSTA as baby steps in Beijing’s quiet, carefully planned annexation of the renegade island. Bit by bit, Mainland Chinese companies backed by the Communist machine (to whom money is no object) will buy up Taiwanese assets and put the country’s economy and national security at risk. The dubious benefits of a hastily-drafted trade agreement are far too high a price to pay for the country’s autonomy. And people don’t need to look far. This kind of creeping economic imperialism is already happening to their cousins in Hong Kong, where signs of gradual Sinofication are everywhere. Before they know it, Hong Kong – and Taiwan for that matter – will become the next Crimea.

There is no telling how much longer the student protestors will stay, or be allowed to stay, in the legislature. Two days ago, Ma Ying-jeou agreed to hold talks with student leaders to try to end the standoff. One proposal is to set up a mechanism for the legislature to scrutinize the implementation of CSSTA and future trade agreements with Mainland China. Whatever the outcome is, the saga has been the best thing that happened to the Democratic Progressive Party (民進黨, the main opposition) since Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) won the presidential election in 2000. Here in Hong Kong, we watch the unfolding events in Taipei with interest and envy. With our own political crisis brewing over the 2017 chief executive election, we wonder if our university students will be as brave as their counterparts in Taipei. We wonder if sunflowers will ever bloom in Hong Kong.

Today's Crimea, tomorrow's Taiwan

Today's Crimea, tomorrow's Taiwan

Published on March 26, 2014 10:10

March 25, 2014

Someone Else’s Party 別人的派對

Late March in Hong Kong brings clammy air, frequent drizzles and the gradual return of the subtropical heat. It is also marked by a spike in beer consumption and hotel room rates, caused not by the arrival of spring but a spectacle known as the Hong Kong Sevens. The three day rugby tournament is much more than just an international sporting event. To expatriates living in Hong Kong, it is a celebration bigger than Christmas and New Year. It is a cross between the Super Bowl, Halloween and Oktoberfest. It is Mardi Gras without the parade and Spring Break with bam bam sticks. The annual carnival fills the Hong Kong Stadium with cheers, beer breath and spontaneous eruptions of song and dance.

That's why they call it a contact sport

That's why they call it a contact sport

Rugby sevens, as the name would suggest, involves fewer players than regular rugby. Each game consists merely of two seven-minute halves. Think of it as beach volleyball or five-a-side soccer. To prove that size doesn’t matter, rugby sevens is set to make its Olympic debut at the 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro.

The first Hong Kong Sevens tournament was held in 1976. The sport was introduced to the British colony by a handful of rugby-loving English businessmen. Securing Cathay Pacific as a corporate sponsor ensured the event’s survival in an otherwise unathletic city. Indeed, the lack of local participation has always been a public relations issue for the Sevens. There wasn’t a single ethnic Chinese on the local team until Fuk-Ping Chan became the first Hong Kong born player to represent the city in 1997. Even today, the “Hong Kong Dragons” look more like the starting lineup of Manchester United than their parochial team name would suggest.

Spot the Asians

Spot the Asians

Rugby is a decidedly English pastime. The sport is dominated by Commonwealth nations around the world. England and ex-British colonies like Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Samoa are favorites at the Hong Kong Sevens, which is why thousands of Brits, Aussies and Kiwis living in Hong Kong flock to the games every year. It didn’t take long before Americans and expats from other non-rugby-playing countries took notice. Rugby fans or not, they jumped on the bandwagon and turned the event into a pan-Caucasian extravaganza. During the Sevens weekend, expats and tourists swamp Hong Kong Stadium and overrun restaurants and bars. The normally quiet Caroline Hill Road in Causeway Bay – the only entry point to the stadium – is packed to the hilt. Streets are cordoned off for crowd control and scalpers are everywhere. Unhired taxis become the hottest commodity in town. The south stand of the stadium is where the rowdiest crowds congregate and minors are denied entry for safety reasons, which also makes it the most exciting place to be in Hong Kong.

Despite all the hullabaloo, the Hong Kong Sevens is a non-event among the locals. Unlike the Standard Chartered Marathon or the Stanley Dragon Boat Championships – both of which draw large local crowds – the Sevens is irrelevant to 95% of the city’s population and receives little to no coverage from the Chinese press. If it weren’t for the backed up traffic in Causeway Bay during that weekend, most locals wouldn’t even know that there was a tournament happening. For three days in March, Hong Kong Stadium is a sea of gweilo holding a beer in one hand and a hot dog in the other. It is as odd as going to the French Open and finding the Roland Garros Stadium full of, say, Japanese faces. If you look hard enough, you may spot the occasional local Hong Konger trying to blend in. To the average rugby-indifferent local, the Sevens is nothing but a tourist trap designed by businesses to promote air travel and boost hotel occupancy. With all the money visitors splurge on tickets, food, accommodation and official merchandise, the Hong Kong Sevens is easily the city’s biggest weekend in terms of tourism dollars.

Feels just like home

Feels just like home