Jason Y. Ng's Blog, page 3

August 24, 2016

Legco Election Special: Part 2 - Kowloon East

The second installment of our Legislative Council (Legco) election series takes us to Kowloon East, where three candidates I select from the opposition camp are given an opportunity to make their case to you by answering my five questions.

Incidentally, my top picks in Kowloon East all share the same last name: Tam (none of them is related to each other). They are Frontier’s Mandy Tam Heung-man (candidate #4), Civic Party’s Jeremy Tam Man Ho (candidate #9) and People Power’s “Fast Beat” Tam Tak Chi (candidate #12).

Read Part 1 - Hong Kong Island .

Get out and vote!

Get out and vote!* * *

Question 1: Beyond rhetoric and slogans, what concrete action or achievements can you point to that distinguish you from other candidates?

Mandy : I’ve been doing district work in Kowloon East for over 20 years – that’s not a claim that many of my opponents can make. Furthermore, I was a Legco member between 2004 and 2008, which has given me valuable experience working with other lawmakers and understanding the ins and outs of the legislative process.

Jeremy : My background is transport engineering, an area in which the current Legco lacks expertise. I also have ample district work experience, having assisted residents in Laguna City [a large-scale residential development in Kwun Tong] in thwarting a proposal to build a hotel on Cha Kwo Ling Road, which effort had prevented a huge loss of public space.

In the past year, I’ve devoted much of my time to the so-called “Bag-gate” incident [in which C.Y. Leung was accused of using his position as chief executive to let his daughter bypass airport security]. I organized a petition to collect nearly 36,000 signatures from concerned citizens. I even flew to Bangkok to submit a complaint letter to the regional office of the International Civil Aviation Organization. I believe Legco needs new blood like myself who can work effectively both within and without the legislature.

Fast Beat : I’m a fighter who believes in active resistance. I can think outside the box and will exhaust every possible procedural means in the Legco rulebook to raise our government’s political cost and hold them accountable. I believe that’s the only way they would back down and make compromises.

Mandy is a seasoned politician and a

Mandy is a seasoned politician and a stalwart advocate for civil nomination

in the chief executive election

Question 2: If you win, what issue(s) will you put at the top of your agenda and why?

Mandy : The two items that top my agenda are genuine universal suffrage with civil nomination [the proposal to allow individual citizens to nominate candidates in the chief executive election] and better retirement protection.

On the second issue, I’ll push the government to raise the amount of fruit money [old age allowance] to $3,500 a month [from the current level of $1,290] without requiring a means test. Our elderly have worked their whole life for Hong Kong and it’s time we showed them some respect by providing a reasonable pension.

Jeremy : I support the use of Legco’s Powers and Privileges Ordinance to look into the recent series of management reshuffle at the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), and determine whether it was the handy work of certain Beijing loyalists. The ICAC is a source of pride for Hong Kongers and probity has long been a cornerstone in our society. We won’t allow it to be destroyed by individuals who put themselves above the law.

Fast Beat : My focus will be universal suffrage. I’ll push for a reboot of the failed electoral reform in 2015. I see that as the only effective way to protect our city and safeguard our civil liberties. It’s also the only way to achieve true autonomy.

Jeremy is a commercial pilot who wants

Jeremy is a commercial pilot who wantsto bring aviation expertise and

a breath of fresh air to Legco

Question 3: Our legislative process is plagued with the stubborn existence of the functional seats and unfair rules such as the “separate vote count” mechanism. When the system is so heavily stacked against the opposition, what will you do differently and what are you prepared to do that your predecessors haven’t already tried?

Mandy : I admit it’s very difficult for us to change the separate vote count and other unfair Legco rules. One possible solution is to put more pan-democrats in the functional constituencies to garner enough votes in the legislature to abolish those seats.

Jeremy : I believe every bill that comes through Legco should be carefully reviewed and sufficiently debated. In recent years, the government has been ramming controversial policies and funding requests through the legislature with increasing impunity. In response, I’m prepared to use all non-violent means, including filibusters, to resist bad legislation. At the same time, I’ll work outside Legco to garner public support for these efforts.

Fast Beat : I firmly believe in active resistance. Over the past four years, my People Power colleagues have been effective in reining in the government using various procedural tactics.

We could have been even more effective if there were more of us. What we need is a handful more lawmakers from People Power and the League of Social Democrats working in Legco to strengthen our voice and put more pressure on our government.

Fast Beat is a self-described fighter who

Fast Beat is a self-described fighter whobelieves the CCP will crumble like

the Berlin Wall

Question 4: What is your stance on independence? Do you either condemn or support the movement?

Mandy : I don’t support the independence movement. I’m not convinced that it’s the right thing to do at the moment.

Jeremy : I personally don’t support the independence movement, but I strongly believe that Hong Kongers should have a say in determining our fate beyond 2047 [when the one country, two systems policy ends].

Fast Beat : My People Power colleagues and I want true autonomy for Hong Kong – we can have something akin to the Tibetan government in exile. To achieve that, we have come up with a half-dozen proposed amendments to the Basic Law.

I don’t know whether the Basic Law would survive after 2047. I believe it’s pointless, even unethical, to negotiate our future with the autocratic regime in China. If the Soviet Bloc could collapse overnight, and if the Berlin Wall could come down in an instant, then why can’t the Chinese Communist Party?

Question 5: If you had to choose the next chief executive from the pro-Beijing camp, whom would you pick and why?

Mandy : I won’t choose anyone from the pro-Beijing camp, and I refuse to participate in an election with pre-determined candidates. As I mentioned earlier, the only form of chief executive election I’ll accept is one that involves some form of civil nomination.

Jeremy : I’ll only vote for someone who supports a truly democratic election without any pre-screening and rejects the 8/31 framework [an announcement concerning the 2017 chief executive election issued by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on August 31st, 2014, that rejected, among other things, civil nomination].

Fast Beat : I won’t endorse or vote for any candidate in a “small circle” election [at present, only members of an exclusive election committee have the right to select the chief executive]. I simply won’t accept any form of chief executive election without one person, one vote or civil nomination.

_________________

Other top-of-the-ticket Legco candidates in the Kowloon East geographical constituency include Wong Kwok-kin, Wu Sui-shan, Patrick Ko Tat-pun, Paul Tse Wai-chun, Wilson Or Chong-shing, Lui Wing-kei, Wu Chi-wai, Wong Yeung-tat and Chan Chak-to.

________________________

This article also appears on Hong Kong Free Press.

Published on August 24, 2016 21:03

August 2, 2016

Zhongxiao, Who Has Abandoned You? 中校,你被誰拋棄?

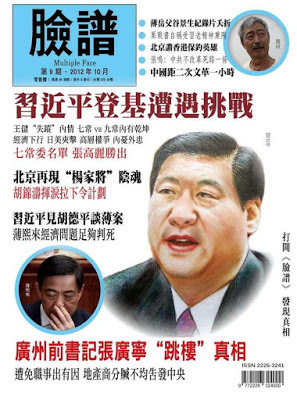

Last week, a Shenzhen district court sentenced Wang Jianmin (王健民), the 62-year-old publisher of Hong Kong-based political tabloids Multiple Face (《臉譜》) and New Way Monthly (《新維月刊》), to five years and three months in prison. His editor-in-chief, 41-year-old Guo Zhongxiao (咼中校), received two years and three months. Their crime? Selling magazines in China without state approval.

The sentencing of the two Hong Kong journalists drew immediate comparisons to the abduction of the five booksellers earlier this year. Events that would have been dismissed as isolated incidents now look increasingly like a pattern. They form part of a broader context in which these and future crackdowns on the city’s press freedom must be analyzed.

Yet, did we let the jailed journalists’ domicile temper our public outrage?

Guo (right) and Wang

Guo (right) and WangI met Guo five years ago on social media. At the time, he was a staff editor for the Hong Kong newsmagazine Yazhou Zhoukan (《亞洲週刊》or Asia Weekly). His Facebook posts, alternating between commentaries on Chinese politics and selfies from his hiking exploits on the MacLehose Trail, caught my eye. In a city where people were never more than three degrees of separation apart, we quickly became friends.

Every once in a while, ZX – which was how I addressed him – and I would meet up for lunch to share thoughts on politics, blogging and digital journalism. A Hubei native, he would speak Mandarin to me and I would respond in Cantonese. We communicated just fine – only on rare occasions did we resort to scribbling Chinese characters on restaurant napkins.

ZX was something of an Internet celebrity in China. The blogger-cum-social activist got his big break in 2002 when his blog article “Shenzhen, who has abandoned you?” (《深圳,你被誰拋棄?》) went viral on social media in the mainland. The 10,000-word manifesto, which criticized city officialdom for not doing enough to maintain Shenzhen’s competitiveness, earned him a meeting with the mayor. In Chinese politics, that’s about as rare as a hunk of mutton-fat jade.

Using his blogosphere stardom, ZX went on to co-found Interhoo (因特虎), an online think tank that advised government officials on economic policies. In 2003, he was named “Netizen of the Year” and one of China’s top ten citizen journalists. His claim to fame landed him a coveted job offer a year later from the prestigious Asia Weekly in Hong Kong.

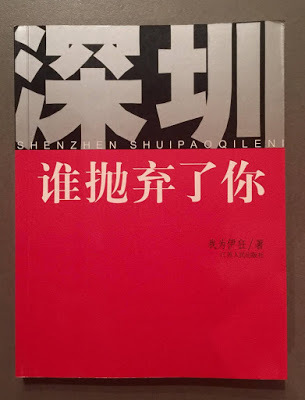

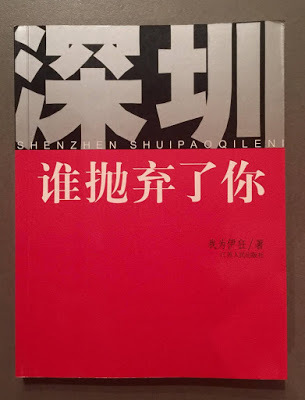

ZX's book, published under an alias in 2003

ZX's book, published under an alias in 2003ZX’s success story inspired me to write a short story titled “ Going South ”, published in an English-language anthology in 2012 – roughly a year after we first made our acquaintance on Facebook. In April, I booked him for lunch near his office in Chai Wan to give him my new book. In return, he gifted me a signed copy of Shenzhen Shuipaoqileni, a book he authored under an alias based on the blog article that had started it all.

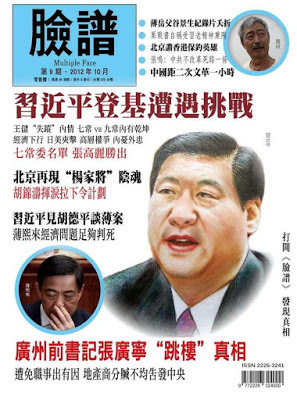

It might have been at the same lunch that ZX told me his plan to leave his job to become editor-in-chief of two young political tabloids, Multiple Face and New Way Monthly. After spending eight years cutting his teeth at Asia Weekly, he was ready to flex his muscles elsewhere.

The two magazines specialized in exposés on the Communist leadership. The intense power struggles among rival factions and the often salacious private lives of high-level party members – the same topics covered ad nauseam by the publishing house operated by the missing Hong Kong booksellers – made for sensational reading. The spectacular downfall of the once-political superstar Bo Xilai (薄熙來) in early 2012 had further fuelled the demand for tabloid journalism and played a part in persuading ZX to seek greener pastures.

But ZX’s career change wasn’t the only move he had in mind. The mainland expatriate had just become a permanent resident of Hong Kong and could not wait to move back to Shenzhen with his wife and newborn child to save on housing expenses. His newly-minted Hong Kong ID would allow him to commute between the two cities with relative ease. Always a skeptic, I reminded him the risk of living in mainland China and writing so liberally about it. Still, he was willing to take his chances.

A 2012 edition of Multiple Face

A 2012 edition of Multiple FaceIf life is a gamble, then my friend had rolled the dice and lost. If he ever thought that writing for a magazine was less risky than running one, or that a Hong Kong citizen working in the mainland enjoys the same relative immunity as do his Western counterparts, then he would have been grossly mistaken.

In May 2014, less than two years after his move, ZX, along with the magazines’ publisher Wang Jianmin, was taken away by Chinese authorities. Upon learning about their disappearances in the news, I tried contacting my friend by phone and by email but to no avail. I asked for assistance on social media and reached out to a number of pan-democratic lawmakers, but nothing came of that either. Pleading with the Hong Kong government to intervene diplomatically seemed out of the question.

My call for help had largely fallen on deaf ears. Perhaps the capture of two mainland-born journalists – who have decidedly mainland-sounding names and who can barely speak a word of Cantonese, despite their permanent resident status – did not give the matter a sufficient “nexus” to Hong Kong for local politicians or journalists’ groups to act.

Or perhaps playing the dangerous game of tabloid journalism while living in the mainland was so patently unwise that their run-ins with authorities were considered “fair game.” Among the people I talked to, there was a palpable sense of “What were they thinking?”

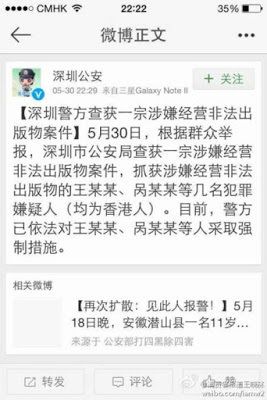

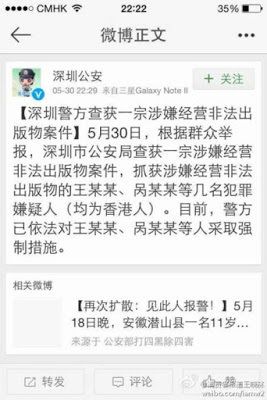

Shenzhen Police sent out a tweet on 30 May

Shenzhen Police sent out a tweet on 30 May 2012 announcing Guo's arrest

It was not the only time that the domicile of an arrestee mattered in public opinion. The disappearance of Lui Bo (呂波), a Shenzhen resident and the first of the five Hong Kong booksellers to go missing, was a virtual non-event in the local news cycle. The incident did not gain traction with the media until two months later when his Hong Kong-based colleague Lee Po (李波) was believed to be abducted in Hong Kong by Chinese authorities.

To the uninitiated, apathy can also be easily rationalized. People I approached for help cautioned that making a lot of noise south of the border might hurt more than help, considering that the accused were already in Chinese custody at the mercy of their captors. Besides, Communist operatives were not known to bow to public pressure in Hong Kong and it was advisable to let the legal process run its course.

With that, the case faded into oblivion. In the intervening months, so much had happened in Hong Kong and abroad that depressed and distracted us: the Occupy Movement, the rise of localism, terrorist attacks in Europe, Brexit, Donald Trump. If it weren’t for the easy comparison to the missing booksellers saga, the journalists’ sentencing last week wouldn’t have even registered a pulse in the press.

ZX is due to be released as early as the end of this month – he gets credit for the 26 months he has already served while in detention. When he finally regains his freedom and somehow manages to make his way back to Hong Kong, I will tell him how immeasurably sorry I am about his ordeal. I will tell him how utterly absurd it was for a magazine editor to be convicted for running an illegal business. I will also tell him what happened to him may just as easily happen to any of us, and that our collective inaction was short-sighted, if not altogether shameful. And I hope he can find it within himself to forgive me and all those who have failed him.

Protest in support of the missing booksellers

Protest in support of the missing booksellers________________________

This article also appeared on SCMP.com.

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on August 02, 2016 06:49

Zhongxiao, Who Has Abandoned You?

Last week, a Shenzhen district court sentenced Wang Jianmin (王健民), the 62-year-old publisher of Hong Kong-based political tabloids Multiple Face (《臉譜》) and New Way Monthly (《新維月刊》), to five years and three months in prison. His editor-in-chief, 41-year-old Guo Zhongxiao (咼中校), received two years and three months. Their crime? Selling magazines in China without state approval.

The sentencing of the two Hong Kong journalists drew immediate comparisons to the abduction of the five booksellers earlier this year. Events that would have been dismissed as isolated incidents now look increasingly like a pattern. They form part of a broader context in which these and future crackdowns on the city’s press freedom must be analyzed.

Yet, did we let the jailed journalists’ domicile temper our public outrage?

Guo (right) and Wang

Guo (right) and WangI met Guo five years ago on social media. At the time, he was a staff editor for the Hong Kong newsmagazine Yazhou Zhoukan (《亞洲週刊》or Asia Weekly). His Facebook posts, alternating between commentaries on Chinese politics and selfies from his hiking exploits on the MacLehose Trail, caught my eye. In a city where people were never more than three degrees of separation apart, we quickly became friends.

Every once in a while, ZX – which was how I addressed him – and I would meet up for lunch to share thoughts on politics, blogging and digital journalism. A Hubei native, he would speak Mandarin to me and I would respond in Cantonese. We communicated just fine – only on rare occasions did we resort to scribbling Chinese characters on restaurant napkins.

ZX was something of an Internet celebrity in China. The blogger-cum-social activist got his big break in 2002 when his blog article “Shenzhen, who has abandoned you?” (《深圳,你被誰拋棄?》) went viral on social media in the mainland. The 10,000-word manifesto, which criticized city officialdom for not doing enough to maintain Shenzhen’s competitiveness, earned him a meeting with the mayor. In Chinese politics, that’s about as rare as a hunk of mutton-fat jade.

Using his blogosphere stardom, ZX went on to co-found Interhoo (因特虎), an online think tank that advised government officials on economic policies. In 2003, he was named “Netizen of the Year” and one of China’s top ten citizen journalists. His claim to fame landed him a coveted job offer a year later from the prestigious Asia Weekly in Hong Kong.

ZX's book, published under an alias in 2003

ZX's book, published under an alias in 2003ZX’s success story inspired me to write a short story titled “ Going South ”, published in an English-language anthology in 2012 – roughly a year after we first made our acquaintance on Facebook. In April, I booked him for lunch near his office in Chai Wan to give him my new book. In return, he gifted me a signed copy of Shenzhen Shuipaoqileni, a book he authored under an alias based on the blog article that had started it all.

It might have been that same lunch when ZX told me his plan to leave his job to become editor-in-chief of two young political tabloids, Multiple Face and New Way Monthly. After spending eight years cutting his teeth at Asia Weekly, the move was considered an overdue promotion.

The two magazines he was about to join specialized in exposés on the Communist leadership. The intense power struggles among rival factions and the often salacious private lives of high-level party members – the same topics covered ad nauseam by the publishing house operated by the missing Hong Kong booksellers – made for sensational reading. The spectacular downfall of the once-political superstar Bo Xilai in early 2012 had further fuelled the demand for tabloid journalism and might have persuaded ZX to seek greener pastures.

But ZX’s career change wasn’t the only move he had in mind. The mainland expatriate had just become a permanent resident of Hong Kong and could not wait to move back to Shenzhen with his wife and newborn child to save on housing expenses. His newly-minted Hong Kong ID would allow him to commute between the two cities with relative ease. Always a sceptic, I reminded him the risk of living in mainland China and writing so liberally about it. Still, he was willing to take his chances.

One of the editions of Multiple Face

One of the editions of Multiple FaceIf life is a gamble, then my friend had rolled the dice and lost. If he ever thought that writing for a magazine was less risky than running one, or that a Hong Kong citizen working in the mainland was no more vulnerable than their Western counterparts, then he would have been grossly mistaken.

In May 2014, less than two years after his move, ZX, along with the magazines’ publisher James Wang, was taken away by Chinese authorities. Upon learning about their disappearances in the news, I tried contacting my friend by phone and by email but to no avail. I asked for assistance on social media and reached out to a number of pan-democratic lawmakers, but nothing came of that either. Pleading with the Hong Kong government to interfere diplomatically seemed out of the question.

My call for help had largely fallen on deaf ears. Perhaps the capture of two mainland-born journalists – who have decidedly mainland-sounding names and who can barely speak a word of Cantonese, despite their PR status – did not give the matter a sufficient nexus to Hong Kong for local politicians or journalists’ groups to act.

Or perhaps playing the dangerous game of tabloid journalism while living in the mainland was so patently unwise that their run-ins with authorities were considered “fair game.” Among the people I talked to, there was a palpable sense of “What were they thinking?”

Shenzhen Police sent out a tweet on 30 May

Shenzhen Police sent out a tweet on 30 May 2012 announcing Guo's arrest

It was not the only time that the location of an arrest mattered in public opinion. The disappearance of Lui Bo, a Shenzhen resident and the first of the five Hong Kong booksellers to go missing, was a virtual non-event in the local news cycle. The incident did not gain traction with the media until two months later when his colleague Lee Po was believed to be abducted by Chinese authorities while he was in Hong Kong.

To the uninitiated, apathy can be easily rationalized. People I approached for help cautioned that making a lot of noise south of the border might hurt more than help, considering that the accused were already in Chinese custody at the mercy of their captors. Besides, Communist operatives were not known to bow to public pressure in Hong Kong and it was advisable to let the legal process run its course.

With that, the incident faded into oblivion. In the intervening months, so much had happened in Hong Kong and abroad that either depressed or distracted us: the Occupy Movement, the rise of localism, terrorist attacks in Europe, Brexit, Donald Trump. If it were not for the easy comparison to the missing booksellers saga, the journalists’ sentencing last week would have barely registered a pulse in the press.

ZX is due to be released as early as the end of this month – he gets credit for the 26 months he has already served while in detention. When he finally regains his freedom and somehow manages to make his way back to Hong Kong, I will tell him how immeasurably sorry I am about his ordeal. I will tell him how utterly absurd it was for a magazine editor to be convicted for running an illegal business. I will also tell him what happened to him may just as easily happen to any of us, and that our collective inaction was short-sighted, if not altogether shameful. And I hope he can find it within himself to forgive me and all those who have failed him.

Protest in support of the missing booksellers

Protest in support of the missing booksellers________________________

This article also appeared on SCMP.com.

Published on August 02, 2016 06:49

July 15, 2016

Unfit for Purpose 健身中伏

Twenty years ago, a Canadian entrepreneur walked down Lan Kwai Fong and had a Eureka moment. Eric Levine spotted an opportunity in gym-deficient Hong Kong and opened the first California Fitness on Wellington Street, a few steps away from the city’s nightlife hub. Business took off and by 2008 the brand had flourished into two dozen health clubs across Asia. There was even talk about taking the company public on the Hong Kong Exchange.

Then things started to go south. The chain was sold, broken up and resold a few times over. Actor Jackie Chan got involved and exited. The Wellington Street flagship was evicted and shoved into an office building on the fringe of Central, while key locations in Causeway Bay and Wanchai were both lost to rival gyms. What was once the largest fitness chain in Hong Kong began a slow death that preceded the actual one that stunned the city this week.

It needs a corporate workout

It needs a corporate workout

________________________

This article appeared in the 16 July 2016 print edition of the South China Morning Post. You can read the rest of it on SCMP.com.

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Then things started to go south. The chain was sold, broken up and resold a few times over. Actor Jackie Chan got involved and exited. The Wellington Street flagship was evicted and shoved into an office building on the fringe of Central, while key locations in Causeway Bay and Wanchai were both lost to rival gyms. What was once the largest fitness chain in Hong Kong began a slow death that preceded the actual one that stunned the city this week.

It needs a corporate workout

It needs a corporate workout________________________

This article appeared in the 16 July 2016 print edition of the South China Morning Post. You can read the rest of it on SCMP.com.

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on July 15, 2016 06:10

June 26, 2016

Brexit Lessons for Hong Kong 脫歐的教訓

It was an otherwise beautiful, balmy Friday in Hong Kong, if it weren’t for the cross-Channel divorce that put the world under a dark cloud of fright and disbelief.

Asia was the first to be hit by the Brexit shock wave. BBC News declared victory for the Leave vote at roughly 11:45am Hong Kong time – hours before London opened – and sent regional stock markets into a tailspin. The shares of HSBC and Standard Chartered Bank, both listed on the Hong Kong Exchange, plunged 6.5 and 9.5 per cent, respectively. People in this part of the world might not know much about the geopolitics involved (most can’t tell the difference between the United Kingdom, Great Britain and England), but they do know one thing: Brexit is bad for business.

Love did not conquer all

Love did not conquer all

Still, the implications and lessons of the history-making referendum for Hong Kongers extend far beyond the financial markets. For years, the city has been mired in the same populist anger that fueled the Leave campaign in Britain. A backlash against immigration, a yawning wealth gap, and a growing unease toward economic and political integration with the mainland – the same stew of frustrations and fears that has spawned a resurgent nationalism in much of Europe – have given birth to the localist movement in Hong Kong.

The fallout of the Occupy protests in 2014 has stoked that populist fury further. The post-movement emotional void has left the political field wide open for the likes of Wong Yeung-tat and Edward Leung – our own Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson – to preach their right-wing gospel, especially to the disenfranchised youth.

While Hong Kongers can safely assume that they will never be given the right to hold a referendum to “exit” China, localist political parties continue to build a separatist platform on public anxieties and Sinophobia. That they have yet to come up with a single idea, let alone detailed plans, to secede from China has not stopped them from waving the colonial flag and touting an independent Hong Kong state.

In the meantime, populist sentiments have found other ways to manifest themselves in civil society. Like their counterparts in Britain, localist parties in Hong Kong have made easy scapegoats of immigrants and visitors for every social ill. Cross-border traders and Mandarin-speaking shoppers continue to be heckled and harassed. Proposals to extend basic welfare to newcomers from the mainland are met with protests and verbal assaults. Racial slurs such as “locust” and zhinaren (a derogatory term for Chinese people coined by Japanese invaders more than a century ago) are used liberally on social media to refer to the stereotypical mainlander who squats, spits, litters, urinates and even defecates in public.

Nigel Farage (left) and Boris Johnson

Nigel Farage (left) and Boris Johnson

That brings us back to Friday’s referendum. The day after what felt like Armageddon, liberal media in Britain reported some voters on the Leave side expressing regret and confusion. Some complained that they had been misled by fear-mongering politicians, while others claimed they did not know their vote would count. Google Trends recorded a significant spike in the number of people asking “What happens if we leave the EU?” after the polls had closed, suggesting that many did not know why they voted to stay or exit the world’s biggest single market.

While it may be too late for Britain, it is not for the rest of the world. Across the Atlantic, left-leaning pundits are urging Americans to learn a lesson from Brexit and not succumb to Donald Trump’s hate-filled “Put America First” campaign. At the same time, there is just as much for Hong Kongers to learn from the fallout in Britain.

Voters in the upcoming Legislative Council election would be wise to take a closer look at what localist parties like Civic Passion and HK Indigenous are really selling. Before they cast their votes in September, they would be well-served to look beyond those catchy slogans and lofty promises and demand concrete answers on policies and issues. Above all, citizens should recognize that blaming mainlanders for social injustices and Beijing’s political intervention is not only irrational but also morally indefensible.

HKexit?

HKexit?

The economic ramifications of Brexit will not be felt for some time – the divorce settlement will take years to negotiate. Politically, it remains anyone’s guess whether and how soon the Leave vote will trigger an independence referendum in Scotland and Northern Ireland, or how much momentum that right-ring parties in other member states can gather to leave the EU.

The social impact, on the other hand, is more immediate. If humble Hong Kong can, too, offer Britain a lesson, it would be that far from settling a longstanding existential debate, Brexit has only torn, and will continue to tear, the very fabric of British society. Indeed, the rapid polarization and radicalization witnessed in post-Occupy Hong Kong were furiously underway in Britain as soon as the votes were tallied. Just as Occupy left us deeply divided into the yellow and blue ribbons, the young and the old, the fearless and the fearful, last week’s referendum has spawned increasingly nasty debate on social media, and in pubs and across dining tables up and down the not-so-United Kingdom. Remain voters are now called sore losers and Leave supporters are branded as racist xenophobes.

These wounds will fester long before they scab over. They will take years, if ever, to heal. Hong Kong is the living proof of it.

Xenophobia running amok in Britain

Xenophobia running amok in Britain

Asia was the first to be hit by the Brexit shock wave. BBC News declared victory for the Leave vote at roughly 11:45am Hong Kong time – hours before London opened – and sent regional stock markets into a tailspin. The shares of HSBC and Standard Chartered Bank, both listed on the Hong Kong Exchange, plunged 6.5 and 9.5 per cent, respectively. People in this part of the world might not know much about the geopolitics involved (most can’t tell the difference between the United Kingdom, Great Britain and England), but they do know one thing: Brexit is bad for business.

Love did not conquer all

Love did not conquer allStill, the implications and lessons of the history-making referendum for Hong Kongers extend far beyond the financial markets. For years, the city has been mired in the same populist anger that fueled the Leave campaign in Britain. A backlash against immigration, a yawning wealth gap, and a growing unease toward economic and political integration with the mainland – the same stew of frustrations and fears that has spawned a resurgent nationalism in much of Europe – have given birth to the localist movement in Hong Kong.

The fallout of the Occupy protests in 2014 has stoked that populist fury further. The post-movement emotional void has left the political field wide open for the likes of Wong Yeung-tat and Edward Leung – our own Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson – to preach their right-wing gospel, especially to the disenfranchised youth.

While Hong Kongers can safely assume that they will never be given the right to hold a referendum to “exit” China, localist political parties continue to build a separatist platform on public anxieties and Sinophobia. That they have yet to come up with a single idea, let alone detailed plans, to secede from China has not stopped them from waving the colonial flag and touting an independent Hong Kong state.

In the meantime, populist sentiments have found other ways to manifest themselves in civil society. Like their counterparts in Britain, localist parties in Hong Kong have made easy scapegoats of immigrants and visitors for every social ill. Cross-border traders and Mandarin-speaking shoppers continue to be heckled and harassed. Proposals to extend basic welfare to newcomers from the mainland are met with protests and verbal assaults. Racial slurs such as “locust” and zhinaren (a derogatory term for Chinese people coined by Japanese invaders more than a century ago) are used liberally on social media to refer to the stereotypical mainlander who squats, spits, litters, urinates and even defecates in public.

Nigel Farage (left) and Boris Johnson

Nigel Farage (left) and Boris JohnsonThat brings us back to Friday’s referendum. The day after what felt like Armageddon, liberal media in Britain reported some voters on the Leave side expressing regret and confusion. Some complained that they had been misled by fear-mongering politicians, while others claimed they did not know their vote would count. Google Trends recorded a significant spike in the number of people asking “What happens if we leave the EU?” after the polls had closed, suggesting that many did not know why they voted to stay or exit the world’s biggest single market.

While it may be too late for Britain, it is not for the rest of the world. Across the Atlantic, left-leaning pundits are urging Americans to learn a lesson from Brexit and not succumb to Donald Trump’s hate-filled “Put America First” campaign. At the same time, there is just as much for Hong Kongers to learn from the fallout in Britain.

Voters in the upcoming Legislative Council election would be wise to take a closer look at what localist parties like Civic Passion and HK Indigenous are really selling. Before they cast their votes in September, they would be well-served to look beyond those catchy slogans and lofty promises and demand concrete answers on policies and issues. Above all, citizens should recognize that blaming mainlanders for social injustices and Beijing’s political intervention is not only irrational but also morally indefensible.

HKexit?

HKexit?The economic ramifications of Brexit will not be felt for some time – the divorce settlement will take years to negotiate. Politically, it remains anyone’s guess whether and how soon the Leave vote will trigger an independence referendum in Scotland and Northern Ireland, or how much momentum that right-ring parties in other member states can gather to leave the EU.

The social impact, on the other hand, is more immediate. If humble Hong Kong can, too, offer Britain a lesson, it would be that far from settling a longstanding existential debate, Brexit has only torn, and will continue to tear, the very fabric of British society. Indeed, the rapid polarization and radicalization witnessed in post-Occupy Hong Kong were furiously underway in Britain as soon as the votes were tallied. Just as Occupy left us deeply divided into the yellow and blue ribbons, the young and the old, the fearless and the fearful, last week’s referendum has spawned increasingly nasty debate on social media, and in pubs and across dining tables up and down the not-so-United Kingdom. Remain voters are now called sore losers and Leave supporters are branded as racist xenophobes.

These wounds will fester long before they scab over. They will take years, if ever, to heal. Hong Kong is the living proof of it.

Xenophobia running amok in Britain

Xenophobia running amok in Britain

Published on June 26, 2016 22:33

June 19, 2016

Hero’s Return 英雄歸來

It was supposed to be a slow news week. Chief Executive C.Y. Leung was still on holiday and his deputy Carrie Lam had just returned from a nine-day trip to America. The front page story was meant to be the grand opening of Shanghai Disneyland Park and the bizarre sight of Mickey and Mini dancing in gold dresses. The headline? “Snow White spends new wealth on bling from Chow Tai Fook.”

Lam Wing-kee at the press conference

Lam Wing-kee at the press conferenceThen, a bombshell.

Lam Wing-kee (林榮基), one of the five booksellers missing since last winter, came out of the woodwork on Thursday night with shocking revelations about his detention in the mainland. Like a POW who had escaped from enemy camps, Lam gave a blow-by-blow account of his eight-month ordeal in Ningbo – an industrial city south of Shanghai and 1,100 kilometers from Hong Kong – without ever being told his charges or given a phone call. At one point, the captive was put on suicide watch and handed a script for a videotaped confession. During the hastily-held press conference, Lam fought back tears and thanked Hong Kongers for their support. He also called on the public to “say no to tyranny.”

To the viewers watching at home or online, Lam’s testimony confirmed a few things – none of which they didn’t already fear and know.

First, much of the crime and punishment in China is overseen not by the gong’an(mainland law enforcement) but an extrajudicial body called the “Central Special Unit” (中央專案組). It answers only to the Communist Party and allows operatives to bypass whatever limited due process that exists in the law books, such as access to legal representation and a maximum detention period. It is so secretive and powerful that Security Secretary Lai Tung-kwok (黎棟國) nicknamed it the “Mighty Division” (強力部門).

The five missing booksellers

The five missing booksellersSecond, in the event of an arrest in the mainland, neither the SAR government nor the Hong Kong Police can or will do a thing to intervene. During Lam’s eight-month involuntary confinement in Ningbo, neither Lai nor Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen (袁國強) lifted a finger to assist him. On the Legco floor, the bureaucrats paid lip service by “expressing concerns” and promising to “reach out” to their Chinese counterparts. But like that snooty girl at the bar who fakes a phone call to look busy, they probably never even picked up the phone or knew what number to call. Left to his own devices, the arrestee will have to either wait it out or negotiate a plea bargain via a false confession or a lifetime gag order in exchange for a release.

Third, any remaining pretense that the “one country, two systems” framework is intact has been shattered. At the press conference, Lam confirmed that Lee Po (李波), his fellow kidnapped bookseller, had been taken away by force while he was Hong Kong, suggesting that mainland agents are not afraid to make a cross-border arrest if they so choose. No matter how vehemently Lee himself tries to deny that claim, he still has not been able to explain how he managed to enter China without proper travel documents. Any sensible person can tell which man is telling the truth and which man is lying to protect himself and his loved ones.

Brave as it is, Lam’s decision to go public is fraught with enormous peril. He has become a fugitive in his own city. Openly defying the Communist Party can mean harassment and even knife attacks by hired thugs or secret operatives, the same fate that befell Next Media’s Jimmy Lai and Ming Pao’s Kevin Lau. While traveling to China to visit his girlfriend is clearly out of the question, Lam has to look over his shoulder – whether at home or in countries like Thailand – for kidnappers. Then there is the psychological warfare to wrestle with. Local newspapers like the Sing Tao Daily and HK01 have already published damning stories attacking his credibility. Three other missing booksellers, including Lee Po, have gone on record to discredit their outspoken colleague. To avoid reprisals from the authorities, Lam’s girlfriend in Shenzhen has called him a selfish lover and a con man. Every trick on the communist playbook, from character assassination to actual death threats, will be hurled at Lam in the coming weeks and months. It will take a heart of flint and nerves of steel to endure it all.

The smear campaign begins

The smear campaign beginsStill, Lam’s incredible courage to come forward when so many others have stayed silent is not lost on his fellow Hong Kongers. Thousands have braved the summer heat in a march this weekend to show their solidarity. Even the ever-cynical localist groups, who normally have a bone to pick with just about anyone but themselves, have been muted (instead, they ridiculed citizens for attending a “feel-good” rally and berated the pan-dems for turning it into another fundraising event). For a few days, it seems, Hong Kong people have set aside their differences and united to commend Lam’s heroism.

What’s more, for a few days, the Democratic Party – the bane of voters ever since then-chairman Albert Ho’s (何俊仁) Faustian handshake with the Liaison Office that sealed the fate of the 2010 electoral reform – appears to have found redemption. In his most desperate hour, Lam sought the help of not Long Hair or Joshua Wong. Instead, he went straight to Ho and made him his protector at the press conference. In doing so, he reaffirmed Ho’s status as the elder statesman within the pro-democracy camp. If the Legco election were to be held this week, the Democratic Party would have easily turned those brownie points into votes. It is a pity that election day is still 11 weeks away and by then much of the aura will likely have dissipated.

The incident of the missing booksellers has been a game-changer for Hong Kong’s post-Handover relations with the mainland. It has triggered not only widespread anxiety but a new wave of mass emigrations. Equally significant, Lam’s revelations have exposed the Communist Party’s blatant lies and dirty tricks. Half a century after the Cultural Revolution and nearly 20 years into the Handover, little has changed in the leadership’s strategy or mindset. No amount of gold or bling can cover up the party’s stench or camouflage its filth. In the meantime, Hong Kongers have learned to trust no one else but themselves. Lam is right: what happened to him can happen to any of us. We are all in it together.

Mickey and Mini in gold

Mickey and Mini in gold

Published on June 19, 2016 02:23

May 15, 2016

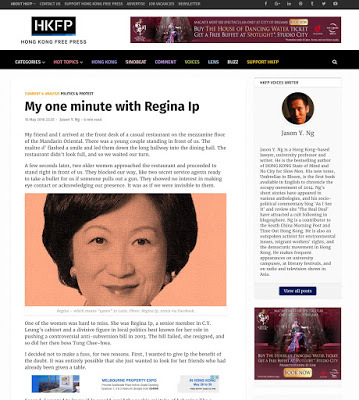

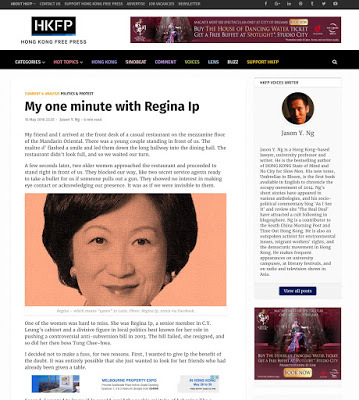

My One Minute with Regina 我和葉劉的一分鐘

My friend and I arrived at the front desk of a casual restaurant on the mezzanine floor of the Mandarin Oriental. There was a young couple standing in front of us. The maître d’ flashed a smile and led them down the long hallway into the dining hall. The restaurant didn’t look full, and so we waited our turn.

A few seconds later, two older women approached the restaurant and proceeded to stand right in front of us. They blocked our way, like two secret service agents ready to take a bullet for us if someone pulls out a gun. They showed no interest in making eye contact or acknowledging our presence. It was as if we were invisible to them.

Regina, which means "queen" in Latin

Regina, which means "queen" in Latin

One of the women was hard to miss. She was Regina Ip, a senior member in C.Y. Leung’s cabinet and a divisive figure in local politics best known for her role in pushing a controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003. The bill failed, she resigned, and so did her then boss Tung Chee-hwa.

I decided not to make a fuss, for two reasons. First, I wanted to give Ip the benefit of the doubt. It was entirely possible that she just wanted to look for her friends who had already been given a table.

Second, I wanted to know if Ip would avoid the rookie mistake of behaving like a swaggering politician. After C.Y. Leung’s now-infamous “bag-gate” incident – the chief executive allegedly pressured airport staff to deliver a forgotten bag to his daughter at the boarding gate in violation of security protocols – it would be far too easy, almost stereotypical, to assume that all self-important government officials act above the law – and basic social etiquette.

And so I waited. Meanwhile, my friend Jeremy, who isn’t from around here, had no idea who this woman with an aggressive hairdo was. He started to give me looks, amused by the queue-jumpers.

The "first family" embroiled in bag-gate

The "first family" embroiled in bag-gate

A few more seconds later, the maître d’ – an impossibly gracious Eurasian woman – returned.

The moment of truth.

The maître d’ walked behind the counter and smiled to me and my friend. I smiled back and said, “For two, pleas….” I hadn’t even finished my sentence when Ip’s female companion lunged forward and made a “V” sign. “Table for two!” she growled.

“Is this woman for real?” Jeremy protested.

Confused, the maître d’ asked politely, “I’m sorry, but who got here first?”

“We did,” I said, giving a slight head tilt.

“But you see, we called the restaurant to let them know we were coming,” Ip finally spoke. I turned and stared at her, transfixed by her warped logic.

Ip saw the look on my face and said, “We really did, you can ask the restaurant!”

I believed her. But it wasn’t the point.

“It doesn’t matter,” she conceded, “You two can go in front of us.”

“No, no, you two go ahead. It doesn’t matter to us either,” I countered, rejecting an offer that implied I was the one who had cut the line.

By then, the maître d’ had heard enough testimony from both plaintiffs and defendants. She must handle this kind of minor disputes several times a day.

“Right this way, gentlemen,” the maître d’ returned a verdict.

As she walked us down the hallway, the maître d’ furrowed her eyebrows and said, “I am really sorry about what just happened.” I wasn’t sure whether the half-Caucasian staffer had recognized Ip, but she wanted to apologize for her just the same.

“It’s not your fault,” Jeremy replied. He then turned to me and said, “Those two need to learn some manners and wait in line like everyone else!”

“Did you know who the taller woman was?” I asked my friend, before giving him a three-minute crash course on local politics.

“I don’t care if she was Michelle Obama!” Jeremy quipped. “Is that how things work in Hong Kong? Do all politicians think they don’t need to follow the rules?”

The "crime scene" at the Mandarin

The "crime scene" at the Mandarin

That last question plunged me into deep thoughts. Jeremy might not know much about local politicians, but his remark summed up their holier-than-thou attitude rather accurately, even over an incident that seemed so insignificant.

I wasn’t angry with Ip. During our 60-second encounter, she was never rude – her companion was – but she wasn’t. She might have even passed for a nice lady. She was careful to avoid clichés like “Do you know who I am?” or “Manager! I need to speak to the manager!” – as so many of her peers would or could have said if placed in a similar situation. Even if she had thought it, she was smart enough not to say it.

Instead, I felt bad for her. As much as I find her political stance regrettable, Ip has a lot going for her. Her public service experience, education credentials and willingness to play ball with Beijing make her a formidable contender for the Government House.

In the end, however, it won’t be her politics (she is an unabashed Beijing loyalist), or her naked ambition (she makes no secret of her aspirations for the top job), or even her superiority complex (she has been caught on camera giving reporters and service people a hard time) that will do her in. She is guilty on all three counts, of course, but none of them is politically fatal.

Her Achilles’ heel is her tone deafness, which explains why she has called foreign domestic workers seductresses of married men, compared wearing animal fur to eating meat, proposed to lock up asylum seekers in detention camps, and believed restaurant lines don’t apply to her if only she gives the manager a heads-up. She honestly believes she is right, convinced by twisted reasoning that makes sense only to her but that fails the most elementary of sanity checks.

For decades, she has been living in a bubble, surrounded by hand-shakers and brown-nosers at her beck and call – like her lunch companion who had no qualms about riding on her coattails to reap even the smallest advantage in life. Over time, she loses the common touch, and so goes the common sense.

If and when she decides to throw her hat into the ring, Ip won’t be running against other hopefuls like John Tsang or Carrie Lam – she will be running against herself. And that’s the toughest battle in the world.

She made enemies of 350,000 FDWs

She made enemies of 350,000 FDWs

________________________

This article also appears on Hong Kong Free Press.

As posted on HKFP.com

As posted on HKFP.com

A few seconds later, two older women approached the restaurant and proceeded to stand right in front of us. They blocked our way, like two secret service agents ready to take a bullet for us if someone pulls out a gun. They showed no interest in making eye contact or acknowledging our presence. It was as if we were invisible to them.

Regina, which means "queen" in Latin

Regina, which means "queen" in LatinOne of the women was hard to miss. She was Regina Ip, a senior member in C.Y. Leung’s cabinet and a divisive figure in local politics best known for her role in pushing a controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003. The bill failed, she resigned, and so did her then boss Tung Chee-hwa.

I decided not to make a fuss, for two reasons. First, I wanted to give Ip the benefit of the doubt. It was entirely possible that she just wanted to look for her friends who had already been given a table.

Second, I wanted to know if Ip would avoid the rookie mistake of behaving like a swaggering politician. After C.Y. Leung’s now-infamous “bag-gate” incident – the chief executive allegedly pressured airport staff to deliver a forgotten bag to his daughter at the boarding gate in violation of security protocols – it would be far too easy, almost stereotypical, to assume that all self-important government officials act above the law – and basic social etiquette.

And so I waited. Meanwhile, my friend Jeremy, who isn’t from around here, had no idea who this woman with an aggressive hairdo was. He started to give me looks, amused by the queue-jumpers.

The "first family" embroiled in bag-gate

The "first family" embroiled in bag-gateA few more seconds later, the maître d’ – an impossibly gracious Eurasian woman – returned.

The moment of truth.

The maître d’ walked behind the counter and smiled to me and my friend. I smiled back and said, “For two, pleas….” I hadn’t even finished my sentence when Ip’s female companion lunged forward and made a “V” sign. “Table for two!” she growled.

“Is this woman for real?” Jeremy protested.

Confused, the maître d’ asked politely, “I’m sorry, but who got here first?”

“We did,” I said, giving a slight head tilt.

“But you see, we called the restaurant to let them know we were coming,” Ip finally spoke. I turned and stared at her, transfixed by her warped logic.

Ip saw the look on my face and said, “We really did, you can ask the restaurant!”

I believed her. But it wasn’t the point.

“It doesn’t matter,” she conceded, “You two can go in front of us.”

“No, no, you two go ahead. It doesn’t matter to us either,” I countered, rejecting an offer that implied I was the one who had cut the line.

By then, the maître d’ had heard enough testimony from both plaintiffs and defendants. She must handle this kind of minor disputes several times a day.

“Right this way, gentlemen,” the maître d’ returned a verdict.

As she walked us down the hallway, the maître d’ furrowed her eyebrows and said, “I am really sorry about what just happened.” I wasn’t sure whether the half-Caucasian staffer had recognized Ip, but she wanted to apologize for her just the same.

“It’s not your fault,” Jeremy replied. He then turned to me and said, “Those two need to learn some manners and wait in line like everyone else!”

“Did you know who the taller woman was?” I asked my friend, before giving him a three-minute crash course on local politics.

“I don’t care if she was Michelle Obama!” Jeremy quipped. “Is that how things work in Hong Kong? Do all politicians think they don’t need to follow the rules?”

The "crime scene" at the Mandarin

The "crime scene" at the MandarinThat last question plunged me into deep thoughts. Jeremy might not know much about local politicians, but his remark summed up their holier-than-thou attitude rather accurately, even over an incident that seemed so insignificant.

I wasn’t angry with Ip. During our 60-second encounter, she was never rude – her companion was – but she wasn’t. She might have even passed for a nice lady. She was careful to avoid clichés like “Do you know who I am?” or “Manager! I need to speak to the manager!” – as so many of her peers would or could have said if placed in a similar situation. Even if she had thought it, she was smart enough not to say it.

Instead, I felt bad for her. As much as I find her political stance regrettable, Ip has a lot going for her. Her public service experience, education credentials and willingness to play ball with Beijing make her a formidable contender for the Government House.

In the end, however, it won’t be her politics (she is an unabashed Beijing loyalist), or her naked ambition (she makes no secret of her aspirations for the top job), or even her superiority complex (she has been caught on camera giving reporters and service people a hard time) that will do her in. She is guilty on all three counts, of course, but none of them is politically fatal.

Her Achilles’ heel is her tone deafness, which explains why she has called foreign domestic workers seductresses of married men, compared wearing animal fur to eating meat, proposed to lock up asylum seekers in detention camps, and believed restaurant lines don’t apply to her if only she gives the manager a heads-up. She honestly believes she is right, convinced by twisted reasoning that makes sense only to her but that fails the most elementary of sanity checks.

For decades, she has been living in a bubble, surrounded by hand-shakers and brown-nosers at her beck and call – like her lunch companion who had no qualms about riding on her coattails to reap even the smallest advantage in life. Over time, she loses the common touch, and so goes the common sense.

If and when she decides to throw her hat into the ring, Ip won’t be running against other hopefuls like John Tsang or Carrie Lam – she will be running against herself. And that’s the toughest battle in the world.

She made enemies of 350,000 FDWs

She made enemies of 350,000 FDWs________________________

This article also appears on Hong Kong Free Press.

As posted on HKFP.com

As posted on HKFP.com

Published on May 15, 2016 06:40

April 27, 2016

Baptism of Fire 炮火的洗禮

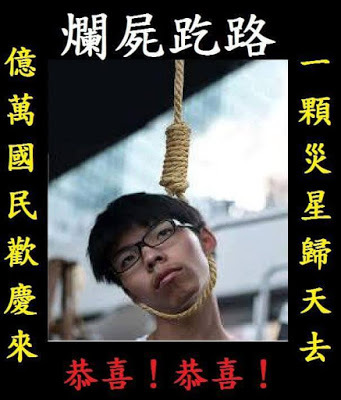

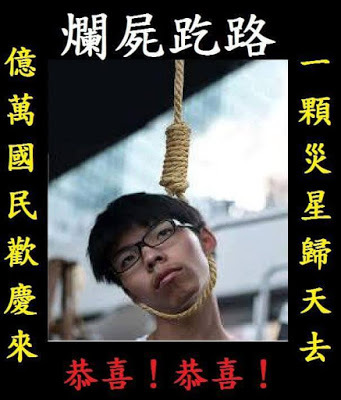

“Drop dead, traitors!” wrote one Facebook user. “Stop swindling money from gullible supporters,” said another. Further down the comment thread, the Photoshopped picture of a young man with a noose tied around his neck received dozens of likes. “Your corpse will rot on the street and we will celebrate!” the caption read.

The lynching victim depicted in the picture was Joshua Wong (黃之鋒), the once-idolized student leader who, at the tender age of 14, led tens of thousands of citizens to thwart the government’s attempt to introduce a patriotic education program. The darling of foreign news media appeared on the cover of Time’s Asia edition and was named one of Fortune magazine’s top 10 world leaders in 2015 alongside Pope Francis and Apple CEO Tim Cook. There were even whispers that he should be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Yesterday's hero

Yesterday's hero

But what a difference a year makes. Today, he is the prime target of what amounts to Cyber-bullying. Thousands of blistering comments plaster across Wong’s Facebook page and that of his newly-minted political party Demosistö (香港眾志). The trolling – the Internet slang for online harassment – is so relentless, and the name-calling is so vicious and disruptive, that you easily forget what the original post is about.

“My five-year honeymoon is over,” said Wong, who turned 19 last October, on the telephone yesterday. He was referring to the early years of his political career when he enjoyed a degree of immunity from criticism. “Now that I’m running my own political party, I expect the public to hold my feet to the fire,” he confessed, admitting that the halo above his head has slipped. “If the criticism is valid,” Wong added, “I take it to heart so I can do better in the future.”

In reality, most of the online commentary is less than constructive. The trolls, who never fail to respond within minutes of a new update, go by aliases like Billy Bong and On Dog Joshua (“on” is an expletive in Cantonese meaning “moronic”). At the same time, there is no shortage of keyboard warriors who use their real accounts under their real names. The vast majority of them are diehard supporters of localist parties such as Hong Kong Indigenous (本土民主前線) and Civic Passion (熱血公民) – radical splinter groups that call on citizens to use “any means necessary” to resist the Sinofication of Hong Kong and ultimately declare independence from Mainland China.

When asked whether the troll army is an organized group mobilized by a political force, Wong explained, “We need to distinguish between localist sympathizers and localist parties, and not lump the two together.” Sympathizers are netizens, according to Wong, and they are uncoordinated and self-motivated. Political parties, on the other hand, are by definition organized groups. Most of the trolls belong to the first category. “Netizens take whatever I say out of context and sometimes put words in my mouth,” Wong protested. “You can reason with a political party, but it’s very difficult to reason with a netizen.”

Don't try to reason with him

Don't try to reason with him

Feeding time at the zoo

While Wong bears the brunt of the vitriol, he is by no means the only target. Fellow Demosistians such as Nathan Law (羅冠聰) and Oscar Lai (黎汶洛) also find themselves in the cross hairs of the ad hominemoffensives.

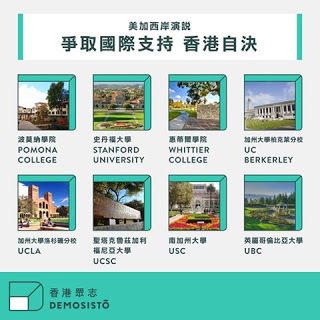

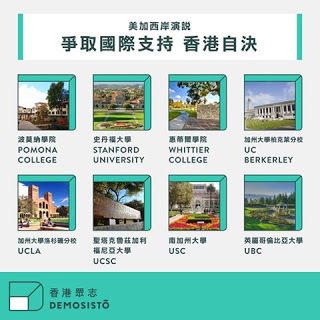

Last week, when Wong and Law embarked on a North American university tour – Wong was invited to speak at Harvard, Yale and M.I.T., among others, while Law focused on Stanford, Berkeley and other West Coast colleges – the attacks reached a fever pitch. The troll army sneered at their “paid vacation” and called it “shameless self-promotion” and an “embarrassment to Hong Kong.” “Who the f** gives you the right to speak for us?” one asked, before a chorus of assailants joined in for an online free-for-all.

“The purpose of the trip was to spread the word about our political situation and rally international support for the self-determination of Hong Kong,” said Law over the telephone, hours before his scheduled flight from San Francisco to Vancouver for a speaking engagement at the University of British Columbia, the final stop on his week-long tour. “We didn’t do any fundraising for Demosistö, and all travel expenses were paid by the universities that invited us,” he added.

When asked about the timing of the trip – less than a month after Demosistö was launched – Law explained: “Until now, Joshua and I had been very busy getting the new party off the ground. At the same time, we had to do the talks before the spring semester ends in North America. That was it – there’s nothing opportunistic about our schedule.”

Wong's and Law's university tour

Wong's and Law's university tour

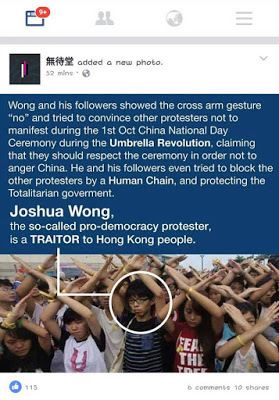

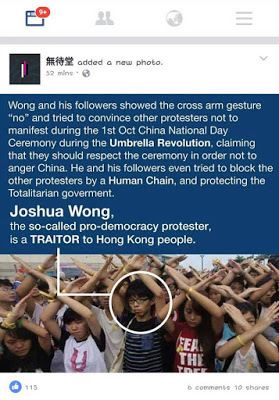

How it all started

The spat between the student leaders and the localists goes way back. During the OccupyMovement of 2014, Wong and the Hong Kong Federation of Students (of which Law was a core member) had constant run-ins with various splinter groups. Four days into the movement, Wong held an anti-government rally outside the Golden Bauhinia Square where the National Day flag-raising ceremony was to take place. Wong and his Scholarism followers were accused of forming a human chain to sabotage the attempt by a legion of firebrand protesters to storm the square to disrupt the event.

“That whole ‘human chain’ accusation was bogus,” Wong argued. “There were dozens of us staging a mass protest that morning. We had turned our backs to the Chinese flag in silent protest and formed crosses with our arms. We never physically stopped anyone from doing anything. It was a misunderstanding that has kept snowballing since then.”

And snowballed it has. The National Day ruckus was followed by similar incidents throughout the 79-day street occupation, in which localist groups challenged the legitimacy of Wong and HKFS leaders to make decisions for protesters and slammed them for standing in the way of escalation plans.

But it gets worse. In the eye of the localist sympathizers, the recent rebranding of Scholarism into Demosistö has turned Wong and Law from ineffective leaders to political rivals – and even election spoilers. That Demosistö and Hong Kong Indigenous will be going after the same voter base – the young, progressive vote – in the September general election has added fuel to the raging fire. That also explains why localist supporters have been going after the new party with more ferocity than they do their declared enemy: Communist China.

Wong accused of sabotaging other protesters' action during Occupy

Wong accused of sabotaging other protesters' action during Occupy

Resistance is futile

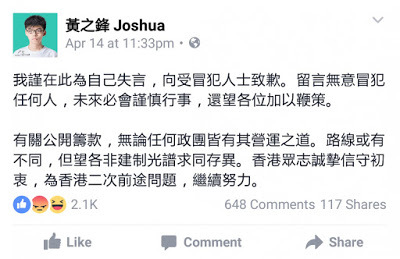

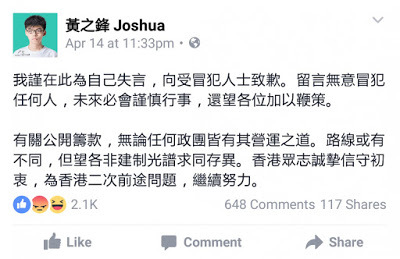

Until recently, the trolling had been one-sided, and the Demosistians had not hit back. Two weeks ago, however, Wong made the mistake of responding to a supporter of Edward Leung (梁天琦), spokesman of Hong Kong Indigenous. The supporter had left a Facebook comment criticizing Demosistö’s $2 million fundraising campaign. Wong defended his solicitation of small online donations with a short reply: “We don’t want to court secret benWong’s regrettable remark was political red meat for the trolls, and the teenager was slaughtered on social media for leveling an unsubstantiated attack against Leung. The next day, Wong issued a public statement on Facebook apologizing for his gaffe. Not surprisingly, the apology was not accepted; it has fired up his critics even more.

“There isn’t much else I can say or do,” said Wong, sounding frustrated and exhausted. “If I am wrong, I stand corrected and I take responsibility for it. But if netizens continue their irrational attacks, I need to stand my ground and push back.”

Apology not accepted

Apology not accepted

As much as Wong and Law try to take the flak in stride, personal insults still sting. The phenomenon underscores the toxicity of local politics and the severe polarization of society in the post-Occupy era. Anger and frustration have boiled over, and once-political allies can become sworn enemies over the slightest of misunderstanding or disagreement.

“[Criticism] comes with the territory,” Wong sighed. “I knew it would be bad, but I didn’t expect it to be this bad.”

Law, on the other hand, takes a more defiant stance. “I’m happy to listen to constructive comments and learn from them,” he said. “But for groundless, malicious attacks, all I can say is: what goes around comes around!”

___________________________

This article appears on SCMP.com under the title "Baptism of fire for Joshua Wong and his nascent political party."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

The lynching victim depicted in the picture was Joshua Wong (黃之鋒), the once-idolized student leader who, at the tender age of 14, led tens of thousands of citizens to thwart the government’s attempt to introduce a patriotic education program. The darling of foreign news media appeared on the cover of Time’s Asia edition and was named one of Fortune magazine’s top 10 world leaders in 2015 alongside Pope Francis and Apple CEO Tim Cook. There were even whispers that he should be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Yesterday's hero

Yesterday's heroBut what a difference a year makes. Today, he is the prime target of what amounts to Cyber-bullying. Thousands of blistering comments plaster across Wong’s Facebook page and that of his newly-minted political party Demosistö (香港眾志). The trolling – the Internet slang for online harassment – is so relentless, and the name-calling is so vicious and disruptive, that you easily forget what the original post is about.

“My five-year honeymoon is over,” said Wong, who turned 19 last October, on the telephone yesterday. He was referring to the early years of his political career when he enjoyed a degree of immunity from criticism. “Now that I’m running my own political party, I expect the public to hold my feet to the fire,” he confessed, admitting that the halo above his head has slipped. “If the criticism is valid,” Wong added, “I take it to heart so I can do better in the future.”

In reality, most of the online commentary is less than constructive. The trolls, who never fail to respond within minutes of a new update, go by aliases like Billy Bong and On Dog Joshua (“on” is an expletive in Cantonese meaning “moronic”). At the same time, there is no shortage of keyboard warriors who use their real accounts under their real names. The vast majority of them are diehard supporters of localist parties such as Hong Kong Indigenous (本土民主前線) and Civic Passion (熱血公民) – radical splinter groups that call on citizens to use “any means necessary” to resist the Sinofication of Hong Kong and ultimately declare independence from Mainland China.

When asked whether the troll army is an organized group mobilized by a political force, Wong explained, “We need to distinguish between localist sympathizers and localist parties, and not lump the two together.” Sympathizers are netizens, according to Wong, and they are uncoordinated and self-motivated. Political parties, on the other hand, are by definition organized groups. Most of the trolls belong to the first category. “Netizens take whatever I say out of context and sometimes put words in my mouth,” Wong protested. “You can reason with a political party, but it’s very difficult to reason with a netizen.”

Don't try to reason with him

Don't try to reason with him

Feeding time at the zoo

While Wong bears the brunt of the vitriol, he is by no means the only target. Fellow Demosistians such as Nathan Law (羅冠聰) and Oscar Lai (黎汶洛) also find themselves in the cross hairs of the ad hominemoffensives.

Last week, when Wong and Law embarked on a North American university tour – Wong was invited to speak at Harvard, Yale and M.I.T., among others, while Law focused on Stanford, Berkeley and other West Coast colleges – the attacks reached a fever pitch. The troll army sneered at their “paid vacation” and called it “shameless self-promotion” and an “embarrassment to Hong Kong.” “Who the f** gives you the right to speak for us?” one asked, before a chorus of assailants joined in for an online free-for-all.

“The purpose of the trip was to spread the word about our political situation and rally international support for the self-determination of Hong Kong,” said Law over the telephone, hours before his scheduled flight from San Francisco to Vancouver for a speaking engagement at the University of British Columbia, the final stop on his week-long tour. “We didn’t do any fundraising for Demosistö, and all travel expenses were paid by the universities that invited us,” he added.

When asked about the timing of the trip – less than a month after Demosistö was launched – Law explained: “Until now, Joshua and I had been very busy getting the new party off the ground. At the same time, we had to do the talks before the spring semester ends in North America. That was it – there’s nothing opportunistic about our schedule.”

Wong's and Law's university tour

Wong's and Law's university tourHow it all started

The spat between the student leaders and the localists goes way back. During the OccupyMovement of 2014, Wong and the Hong Kong Federation of Students (of which Law was a core member) had constant run-ins with various splinter groups. Four days into the movement, Wong held an anti-government rally outside the Golden Bauhinia Square where the National Day flag-raising ceremony was to take place. Wong and his Scholarism followers were accused of forming a human chain to sabotage the attempt by a legion of firebrand protesters to storm the square to disrupt the event.

“That whole ‘human chain’ accusation was bogus,” Wong argued. “There were dozens of us staging a mass protest that morning. We had turned our backs to the Chinese flag in silent protest and formed crosses with our arms. We never physically stopped anyone from doing anything. It was a misunderstanding that has kept snowballing since then.”

And snowballed it has. The National Day ruckus was followed by similar incidents throughout the 79-day street occupation, in which localist groups challenged the legitimacy of Wong and HKFS leaders to make decisions for protesters and slammed them for standing in the way of escalation plans.

But it gets worse. In the eye of the localist sympathizers, the recent rebranding of Scholarism into Demosistö has turned Wong and Law from ineffective leaders to political rivals – and even election spoilers. That Demosistö and Hong Kong Indigenous will be going after the same voter base – the young, progressive vote – in the September general election has added fuel to the raging fire. That also explains why localist supporters have been going after the new party with more ferocity than they do their declared enemy: Communist China.

Wong accused of sabotaging other protesters' action during Occupy

Wong accused of sabotaging other protesters' action during OccupyResistance is futile

Until recently, the trolling had been one-sided, and the Demosistians had not hit back. Two weeks ago, however, Wong made the mistake of responding to a supporter of Edward Leung (梁天琦), spokesman of Hong Kong Indigenous. The supporter had left a Facebook comment criticizing Demosistö’s $2 million fundraising campaign. Wong defended his solicitation of small online donations with a short reply: “We don’t want to court secret benWong’s regrettable remark was political red meat for the trolls, and the teenager was slaughtered on social media for leveling an unsubstantiated attack against Leung. The next day, Wong issued a public statement on Facebook apologizing for his gaffe. Not surprisingly, the apology was not accepted; it has fired up his critics even more.

“There isn’t much else I can say or do,” said Wong, sounding frustrated and exhausted. “If I am wrong, I stand corrected and I take responsibility for it. But if netizens continue their irrational attacks, I need to stand my ground and push back.”

Apology not accepted

Apology not acceptedAs much as Wong and Law try to take the flak in stride, personal insults still sting. The phenomenon underscores the toxicity of local politics and the severe polarization of society in the post-Occupy era. Anger and frustration have boiled over, and once-political allies can become sworn enemies over the slightest of misunderstanding or disagreement.

“[Criticism] comes with the territory,” Wong sighed. “I knew it would be bad, but I didn’t expect it to be this bad.”

Law, on the other hand, takes a more defiant stance. “I’m happy to listen to constructive comments and learn from them,” he said. “But for groundless, malicious attacks, all I can say is: what goes around comes around!”

___________________________

This article appears on SCMP.com under the title "Baptism of fire for Joshua Wong and his nascent political party."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on April 27, 2016 21:40

April 11, 2016

Off to a Rocky Start 香港中箭

Hang Seng Bank has frozen its deposit account. Cybersquatters have occupied its domain name. Its hastily organized press conference, held last Sunday night in a subterranean auditorium, had all the trappings of a student council meeting: it started several hours late and the live streaming on YouTube was interrupted so many times that the number of viewers hovered around 300 and at times dropped below 20.

If that is any indication of the challenges facing Joshua Wong’s new political party, then it is in for a bumpy road ahead.

The launch

The launch

Demosistō, the grown-up version of Scholarism – which Wong founded four years ago to oppose C.Y. Leung’s patriotic education plan – is meant to help the 19-year-old and his posse shed their school boy image to better position themselves for a serious Legislative Council bid in September.

Wong is hoping that the new party with an intelligent-sounding name will wipe the slate clean and allow pro-democracy activists of all ages to join without looking like they are crashing a high school party. For instance, 60-year-old filmmaker Shu Kei (real name Kenneth Ip), who was present at Sunday’s press reference, would have looked oddly out of place if he were to be introduced as a new Scholarism recruit.

A lot of ink has been spilled over the high-profile rebranding, and so far there has been more criticism than praise. The word Demosistō, a portmanteau created by Boy Wonder himself, combines the Greek word for "the people" (demo) and the Latin word for "I stand" (sistō). No one other than Wong himself seems to like the new name. In fact, the word isn’t even grammatically correct: it loosely translates into “I the People stand” (sistō being the first person singular of the verb sistere).

Netizens are quick to call the awkward appellation a public relations blunder, invoking the famous Cantonese proverb that “to be given a bad name is worse than to be born with a bad fate.” One commentator joked that the name sounds like “demolition,” some sort of contraption invented by Joshua Wong to destroy the traditional pan-democratic parties. Other people took issues with the party’s logo that was designed around the letter “D,” saying that it looks like a mobile phone SIM card.

It really does look like a SIM card

It really does look like a SIM card

Things have not gone smoothly for the party’s official website either. The domain name www.demosisto.com has been claimed by an anonymous party. When clicked, the link goes to an empty page with a villainous taunt to Wong: “U still [have] no site?” Outsmarted by their political opponents, Demosistians begrudgingly settled for the next best thing: www.demosisto.hk. A skeletal version of the site was launched hours before the press conference on Sunday.

But that’s not all. Demosistō’s fundraising effort has been stunted by delays in the company registration process, as well as HSBC’s refusal to open a bank account for the party to receive donations. To date, every financial institution approached by Wong has told him to take his business somewhere else.

As a result, all donations had been funneled through deputy secretary-general Agnes Chow’s personal savings account, which presented audit and transparency issues. Then yesterday afternoon, Hang Seng Bank suddenly notified Chow that her account could no longer accept deposits, with immediate effect. The situation just went from bad to worse.

With the entire financial system stacked against them, it remains unclear whether Demosistō will manage to meet its HK$2 million crowd-funding target in time for the Legco election campaign season that is set to begin as early as this summer.

HSBC, one of the self-censoring banks

HSBC, one of the self-censoring banks

The good news is that jokes about names and logos will eventually pass, and that banking and other administrative issues will be sorted out or gotten around somehow. The new party will gain traction and warm to voters as long as it has a solid policy platform. So far, however, Demosistō is long on ideology but short on actionable plans.

The party’s website remains a work-in-progress – the “Policy” tab currently displays a blank page with the words “coming soon” in Chinese. It leaves open the question of where Demosistō stands with respect to policy issues from universal retirement protection to cross-border relations, to the party’s willingness to engage C.Y. Leung’s government and even Beijing officials to break the current political impasse.

What we do know is that Demosistō will continue Wong’s non-violent approach to the fight for universal suffrage and greater autonomy for the city. He has called himself a “centrist” and placed his new party halfway between radical localists who call for Hong Kong’s independence through “any means possible” and the pan-dems who do little more than shout slogans and issue strongly worded statements in response to bad government decisions.